Abstract

Neighborhoods have become the focus of questions about how they affect the families that live within them. A current working assumption of some federal policies is that, with help, households can escape poverty neighborhoods and change their spatial context. How true is this, especially for low-income households, and does changing neighborhoods have measurable benefits? The study uses data from the Moving to Opportunity program, initiated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, to test whether policy interventions by means of housing vouchers have aided moves away from low-poverty areas and into integrated residential settings. By examining the neighborhood demography of the initial and subsequent locations of the samples, it is possible to assess the success of the objectives of decreasing poverty and increasing integration. Although the program has shown some success in assisting households to live in lower-poverty neighborhoods, the findings here emphasize just how difficult it is to intervene in dynamic processes such as housing choice and mobility to create policy outcomes.

Keywords: housing vouchers, poverty, integration

In the past decade, there has been a concerted effort to understand just how a neighborhood can affect individual lives. Does living in a low-income neighborhood or deprived neighborhoods in general have an effect on people's lives, the jobs that they have, and the health that they enjoy? Of particular interest have been outcomes for children. Does growing up in a poor neighborhood inhibit later life chances? This literature has been stimulated in part by observations that poverty concentrations have been increasing, and that the fixed inner-city public housing projects of the past do not seem to have helped low-income and minority households in their search for suitable and safe housing. These questions about neighborhoods and their effects have generated a substantial and growing literature that examines the additive marginal effects of neighborhoods on residential outcomes for inner-city poverty populations (1, 2). That is, after controlling for the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the household, how much additional variance in outcome measures do neighborhood characteristics explain? The literature has struggled with questions of how much variance is attributable to the neighborhood and how much is related to family composition. Although the consensus is still forming, evidence does appear to suggest that place of residence does matter, certainly an outcome that is consistent with much geographic literature on residential location and the impacts of particular places on households (3).

Several specific studies of residential moves between neighborhoods, including studies of the outcomes of residential moves in the Gautreaux program in Chicago, the Hollman settlement in Minneapolis, and the extensive experimental program Moving to Opportunity (MTO), have attempted to evaluate whether households make gains when they change neighborhoods (4). These investigations have used a variety of approaches to examine whether mobility can lead to improved life chances. However, evaluations to date have focused primarily on the initial move and have failed to recognize the impacts of ongoing residential mobility. In this paper, I extend the analysis of previous studies of the outcomes of residential mobility by examining two broad sets of questions about long-term gains from the MTO program. I use Baltimore as a case study. First, is there evidence of living in lower-poverty neighborhoods after residential mobility, and are the gains from residential mobility sustained over time with subsequent moves? Second, do the housing choices lead to living in integrated settings, and again, do these moves to greater residential integration persist over time? Also relevant to neighborhood outcomes are questions about the quality of the neighborhood (including lower crime rates), educational achievement levels, and levels of employment, but these are not examined in this study.

Neighborhoods and Mobility

Residential mobility is a highly structured process with impacts on both the households who move and the places that they choose in their relocation behavior. It is the basic process whereby households improve the quality of their housing and the type of neighborhoods that they inhabit and is intimately connected with urban change as a whole (5). Moves are transitions in people's lives, and neighborhood transitions are the consequences of aggregated individual mobility transitions. Thus, over time, the sum of the myriad decisions by individual households leads to basic changes in the urban structure. Neighborhoods and communities change as people move in and out of them. Over time, these individual moves and the changes that they bring eventually establish the population composition of neighborhoods, and the patterns of land use and the associated patterns of commuting and traffic flows. Mobility is “a consistent and pervasive behavior forming a major element of the policy context; it affects the conditions under which policies are developed and exerts a strong influence on their outcomes” (6).

It is important to distinguish, both in new research and reviews of past research, between individual behaviors that affect neighborhoods and neighborhood effects on individuals. In the first sense, we view mobility as the proximate cause of change, although areas may have high mobility but be stable in population composition. This conceptualization emphasizes individuals as agents who move between places and who change the neighborhoods that they choose. If a large number of minorities choose a neighborhood, they change the ethnic composition of that neighborhood, for example, although the changes also may be more subtle, such as shifts from a neighborhood without young families and children to a neighborhood with them. Within this framework, we can conceptualize neighborhood change as the outcome of individual mobility decisions. Of course, neighborhoods change from factors other than residential mobility; planning decisions with respect to the location of positive and negative externalities and private-sector decisions with respect to capital expenditure also play a role.

In a second conceptualization, the focus is specifically on the neighborhood impacts on individuals who move to that neighborhood. Does the household gain from moving to a particular neighborhood? In this conceptualization, we are asking whether the individual benefits from the context effects of the new neighborhood. If individuals move to a low-poverty neighborhood, do they improve their lives in some sense? The emphasis on context effects arose originally from public health concerns; i.e., reducing concentrated poor-quality housing was seen as necessary to improving public health. It is now clear, however, that health has more to do with poverty than with housing per se.

Recent work on neighborhood conditions emphasizes the role that the neighborhood plays in shaping outcomes for individuals and households. Indeed, as we might expect, other things being equal, people want to live in “good” neighborhoods and to have their children grow up in safe environments. Thus, it is not surprising to find the strong and growing perception among academics and households themselves that growing up in a “bad” neighborhood will likely reduce children's life chances. The reviews of neighborhood effects have tended to emphasize the negative effects of poverty and low-income neighborhoods and concluded that indeed there are outcomes on childhood achievement (7) and on victimization in unsafe neighborhoods (8). In addition to examining neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, studies also have assessed the impact of neighborhood environmental quality on the well-being of residents. Pauleit (9) emphasized the role and value of “green space” in European cities, and it is clear that in the Netherlands, with its long tradition of concern with neighborhood environments, the rural aspects of neighborhoods are often cited by residents as important factors in residential choice (10). Work has demonstrated that the amount of green space in the living environment also positively affects people's (self-reported) health (11).

Anecdotal discussions of neighborhood effects on health outcomes seem to suggest that, even after controlling for socioeconomic status, people in poor neighborhoods fare less well in health outcomes than those in nonpoor neighborhoods (12), or as geographers are fond of saying, geography matters. One explanation suggests that poor neighborhoods create stress, especially for African Americans. The day-to-day stresses of living in areas with poor safety, violence, noise, and housing decay create internal stresses that, in turn, lead to anxiety and depression. Another view emphasizes that actual neighborhood deprivation (i.e., too many bars and fast-food outlets and not enough quality supermarkets) creates the poor health that seems to characterize inner-city minority populations. At the same time, much of the research concern in examining the role of neighborhood effects is to separate out the effects of neighborhood independent of family socioeconomic characteristics. This separation is difficult because of the strong links between household social class and neighborhood status: residents of poor neighborhoods are likely to be poor themselves. As middleclass African-American households left inner-city neighborhoods, they left behind the most impoverished minority households; it is these households who are often most affected by both their socioeconomic status and the neighborhoods that they live in.

It is in this context that the mobility programs have directly investigated the actual effect of neighborhood on the outcomes for those who move into new, more desirable neighborhoods. In broad terms, the mobility programs have a central policy aim to move households from perceived bad neighborhoods to perceived good neighborhoods. Such studies have attempted to separate the true effects of neighborhoods from the effects of families or social networks on the outcomes (13). Tentative results indicated that those who moved to suburban neighborhoods were more likely to be employed and experienced greater neighborhood safety.

At least some of the stimulus for the refocus on neighborhood effects was increasing concern with high poverty concentrations (14). Although why and how poverty concentrations arise remain contested,† there has been a consensus that the concentration of households with housing assistance in specific neighborhoods has not only a negative life-course outcome for such households, but also an overall neighborhood effect beyond the impacts on individual households. The increasing emphasis on geographically dispersing housing-subsidy recipients is thus based on the assumption that residence in concentrated poverty neighborhoods abets socially dysfunctional behavior, or more simply, that poverty households will do better outside of poverty neighborhoods (19). The evidence from an analysis of several studies supports the view that overall, participating tenants do gain from the dispersed moves. However, the gains seem to come not from the lower concentration of poverty per se but from the “structural advantages of the suburban areas, such as schools, public services, and job accessibility” (13). Moreover, there is at least case-study evidence that the suburbs may not be better locations for less educated job seekers (20). The case study of Boston concludes that residential dispersal also is unlikely to be an effective strategy for removing spatial barriers to access to employment for low-income workers. In terms of access to jobs, central cities still provide greater opportunities for these workers.

Mobility, Poverty Dispersal, and Changing Neighborhoods

The concern with neighborhood effects on households crystallized around the notion that concentrated poverty generates negative social effects and thus that reducing concentrated poverty, or dispersing concentrated poverty, would have positive effects on both individuals and neighborhoods (21). Households will gain from their improved neighborhoods, and fewer poor people in a single neighborhood will increase the social status of the neighborhood and, by extension, perhaps make that neighborhood more attractive to potential in-movers. The ideas may not yet have a solid theoretical basis (22), but they have led to substantial investment in measuring such outcomes; in particular, three mobility programs have provided data to examine the outcomes of actual movement through urban neighborhoods.

The mobility programs are, in turn, a reflection of the changing notions of how to provide housing to low-income households. Whereas once the focus was on providing specific projects for low-income households in need of assisted housing, now the emphasis is on giving low-income households a choice within the residential fabric.‡ Whereas once the aim was to provide help at fixed locations, now the Housing Voucher Program, the largest assisted housing program within HUD, aims to help households access housing in the private housing market. The Housing Choice Voucher program grew out of the Experimental Housing Allowance studies of the 1970s and was first initiated as the Section 8 Certificate program. In the 1980s, the Housing Voucher Program was initiated, and the two programs were merged as the Housing Choice Voucher program in 1998.

The first of the evaluations of the effects of moving from a high-poverty neighborhood arose out of litigation over discrimination in the provision of public housing. The outcome of the Gautreaux decision in 1976 was to provide a metropolitan-wide mobility program in which Section 8 subsidies were provided to public housing residents so that they could move from the inner city of Chicago to suburban white communities. Studies of the Gautreaux program provided some evidence that those who moved to suburban communities were more likely to be employed (although the salaries were not necessarily higher) and that suburban youth did better on several educational measures (23, 24). Although these findings could not be considered conclusive evidence in favor of such programs, they did offer insights into the shape of a possibly successful program, one that would require substantial additional housing services if the program were to succeed. At least one of the problems in assessing the Gautreaux program was the substantial dropout rate from the program (23, 24).

A more recent program was focused on the redistribution of low-income public housing residents in Minneapolis and provided some positive findings among the generally mixed outcomes of the program (21). As part of a consent decree in Minneapolis, a large public family complex in the inner city of Minneapolis was demolished (25). The residents of that project created a substantial number of relocated households. An analysis of the data from the Hollman case suggests several important findings for the study of how relocation from inner-city minority neighborhoods will play out at the larger urban scale. Not all residents of the projects that were demolished were willing participants in the relocation project; Southeast Asian households were much more resistant to forced relocation than were African-American households. The study showed that displaced families did not want to move far away from their former homes and most wanted to stay in Minneapolis (21). Those families who indicated a desire to leave the city preferred to move only to the inner ring of suburbs directly north of the city. Preferences for familiar neighborhoods were especially strong among the project residents.

Special Mobility Program participants (a group specified in the Hollman consent decree) were much more likely to move to the suburbs, but the preference of most families (about half of participants) was to stay within Minneapolis. Moving to places near to their original location was an important outcome of the intervention process. More than half of all participants (but 90% of Southeast Asian participants) in the Special Mobility Program stayed in the central city. For this group, neighborhood quality did not change. Those families who moved out of central city neighborhoods gained in quality of living.

Such pilot mobility projects called for more systematic evaluation, and the aim of the MTO program was to find out, in a controlled experiment, what happens when very poor families have the chance to move out of subsidized housing in the poorest neighborhoods of large American cities (26). The program was initiated in 1992 with a mandate from Congress to HUD to test the usefulness of housing vouchers for generating moves away from low-poverty areas and into integrated residential settings. Five cities (Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York) were selected to participate in the program. MTO divided voucher holders into three groups. The control group did not receive a voucher and initially continued to live in public or assisted housing. The Section 8 group received a voucher and regular housing assistance counseling. The experimental group received a voucher and special mobility counseling but was required to move to a low-poverty neighborhood (<10% poverty, according to the 1990 Census).

The most recent summary report of the MTO project (26) suggests that the program has had substantial effects on housing and the neighborhood conditions of participants, especially on perceptions of safety, but mixed effects for educational gains, employment, earnings, and public assistance. Two studies in progress provide analyses showing that experimental households had gains in perceived safety of the neighborhood and that they actually lived in safer neighborhoods (27, 28). But as we will see, although there are sometimes gains for those who moved, in the context of the whole sample, the results may not be quite so positive. Ensuing mobility, after the initial move, reiterates the great difficulty of intervening in the dynamic of household relocation. As Tiebout (29) observed, households vote with their feet, and decisions by governments are always embedded in the dynamic demography of the city. Households move again after their initial relocation, and those moves often undo the advantages of the initial residential move.

The strong gains in self-reported safety and housing quality for MTO and Section 8 movers must be offset with the mixed results with respect to living in reduced-poverty neighborhoods. The final report states that MTO experimental members did not, on average, spend much time in census tracts with lower poverty levels, although there are differences in the neighborhood characteristics for the experimental group and the control group. In addition, nearly half the MTO movers chose neighborhoods that increased in poverty during the 1990s. Perhaps even more telling, but consistent with our knowledge of mobility in general, subsequent moves by the MTO group were often to neighborhoods like the ones they came from and, in some cases, back to their old neighborhoods. Once again, we can identify two forces at work, the changing demography of the city (increases in poverty in inner-city tracts as their demography changed), and housing choices and preferences that favor known neighborhoods where there are friends, family, and support relationships.

To reiterate, the preliminary analyses of the MTO programs have neither focused in detail on the relocation behavior of households over time nor examined the extent to which assisted households have been able to access more integrated residential environments.§ Both questions are relevant in light of discussions about using vouchers to improve neighborhood opportunities and, specifically, the intent of the MTO program (following Gautreaux) to address the residential segregation of minority households. Thus, the following analysis focuses on these questions: Are there long-term gains from the MTO voucher program and especially increases in levels of integration? The findings of this analysis reiterate (i) the difficulty of intervening in the residential mobility process, (ii) the tendency of households, all other things being equal, to move to nearby neighborhoods, (iii) the constraints of moving to more expensive neighborhoods for low-income households, and (iv) the difficulty of creating greater residential integration through housing vouchers.

Research Questions and Analysis

The current research is built around three questions: What are the differences in access to low-poverty neighborhoods between initial and long-term residential relocations for assisted and unassisted households? What are the differences in accessing more-integrated residential neighborhoods between initial and long-term residential relocations for assisted and unassisted households? How do households who did not receive assistance fare in their housing-market decisions?

The Findings from Baltimore: Access to Low-Poverty Neighborhoods.

Experimental movers (MTO movers) in Baltimore made significant initial gains in entering lower-poverty neighborhoods in their first lease-up¶ (Table 1). Of course, this outcome is to be expected, because the program specifically required leasing in a low-poverty neighborhood. Whereas nearly all experimental movers chose neighborhoods that were <20% poverty neighborhoods, only 23% of the regular Section 8 movers did so. The question that is central here is to what extent the experimental and Section 8 movers sustained the original gains after subsequent moves. Households moved, and, of course, neighborhoods change over time.

Table 1. Percent of MTO and Section 8 respondents by their original move location and in their current Baltimore locations by poverty composition of the neighborhood.

| Original move

|

Current location

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % poverty | MTO mover | Section 8 mover | MTO mover | Section 8 mover |

| 0—10 | 40.7 | 6.8 | 24.2 | 8.6 |

| 10—20 | 57.9 | 15.9 | 33.3 | 19.8 |

| 20—30 | 0.7 | 25.8 | 15.8 | 27.6 |

| 30—40 | 0.7 | 36.4 | 14.2 | 23.3 |

| 40—50 | 13.6 | 7.5 | 12.9 | |

| 50—60 | 1.5 | 5.0 | 6.9 | |

| 60—70 | 0.9 | |||

Source: MTO data for Baltimore prepared by HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research. Census data are from the 2000 Census.

The outcomes at the current survey time (2002) are significantly more mixed in terms of the poverty levels of the neighborhoods in which the households live (Table 1). Several different comparisons are possible. The current distribution of the experimental movers is somewhat like the current distribution for the Section 8 movers; even so, the distributions are still significantly different from one another on a Kolmogorov–Smirnov two-sample test (P = 0.01). That is, overall, experimental movers have a higher probability of being in a lower-poverty neighborhood than do regular Section 8 movers. When we compare the distributions of the experimental movers in their initial locations and their current locations, we find that the distributions are significantly different from one another on both χ2 and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests (P = 0.01) We can conclude that although there are initial gains, those gains decline over time. Both additional moves and the changing dynamics of neighborhoods affect the ability to sustain the gains made through the original move to lower-poverty neighborhoods. The contribution of this analysis is to demonstrate that initial gains are difficult to sustain. As I noted earlier, households do not stay put. They move as their life-course needs change, and those moves may not sustain the initial gains made by moves to low-poverty neighborhoods.

An additional issue is that not all households are able to use their vouchers and so do not move. A full test of the program should set the gains for a subset of the sample moves in the context of all households. Only 58% of all experimental households were able to lease up. Of those who were not able to use the experimental voucher, a large number moved anyway. Regular Section 8 voucher holders, who were not constrained to choose a low-poverty neighborhood, were more successful in finding a unit. In Baltimore, 72% of the Section 8 group moved. If we measure the success of the program by including households who were not able to use the experimental voucher and compare their distribution with regular Section 8 voucher holders, the differences across the distributions are quite minor. That is, the overall gains from the MTO program virtually disappear (Table 2). There is no significant difference between the MTO experimental sample of movers plus nonmovers and the control sample, comprised of those who did not receive a voucher. There is no significant difference between experimental movers plus nonmovers and Section 8 movers plus nonmovers. In sum, the special counseling and extra effort to aid experimental movers did not produce gains for the group as a whole, over and above the gains for those who did not receive special help. Interestingly, there is a marginally significant difference (at the P = 0.05 level) between Section 8 movers and nonmovers and the control sample. Clearly, there are differences between movers and nonmovers as we would expect, but to truly evaluate the success of the voucher program, it is essential to consider the total outcome for those who were successful (in moving to a low-poverty neighborhood) and those who were not. It is troublesome for a policy of poverty dispersal that, overall, the current distribution of control households, who received neither vouchers nor experimental help, is only marginally more likely to show households in high-poverty neighborhoods than the aggregate of experimental and control group movers.

Table 2. Percent of total MTO, total Section 8, and baseline respondents by their current Baltimore locations by poverty composition of the neighborhood.

| % poverty | MTO movers and nonmovers | Section 8 movers and nonmovers | Baseline sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0—10 | 15.0 | 6.6 | 3.6 |

| 10—20 | 23.7 | 21.7 | 21.4 |

| 20—30 | 14.5 | 24.7 | 16.1 |

| 30—40 | 17.4 | 18.7 | 15.5 |

| 40—50 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 14.3 |

| 50—60 | 14.5 | 13.3 | 25.6 |

| 60—70 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 3.6 |

Source: MTO data for Baltimore prepared by HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research. Census data are from the 2000 Census. Sample sizes are MTO = 207, Section 8 = 176, baseline = 168.

The Findings from Baltimore: Access to Integrated Neighborhoods. An implicit argument that grows out of the Gautreaux litigation was that mobility would give minority families an opportunity to live in less segregated neighborhoods; the idea was that requiring families to move to low-poverty neighborhoods also would result in desegregation. The title of the MTO program is, in fact, “Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing Demonstration Program,” emphasizing the link of providing support to increase access to integrated housing. In general, as reported by the latest MTO report, the program seems to have been only partially successful in meeting this aim (26).

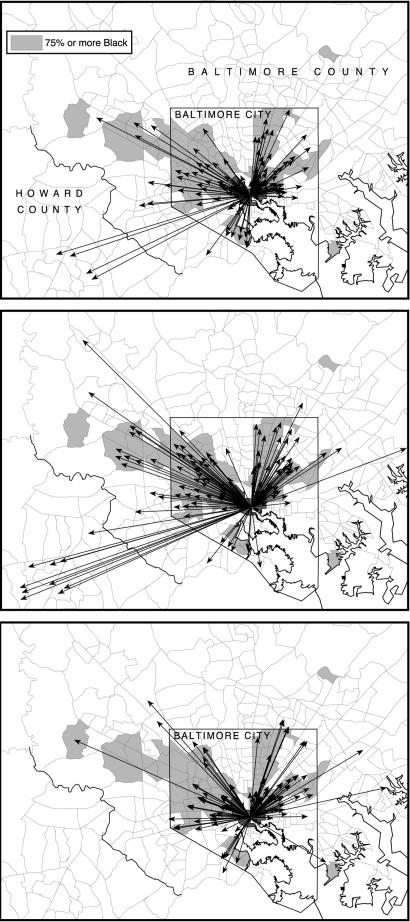

A specific analysis of the effects of moving on racial patterns in Baltimore confirms the difficulty in using vouchers to increase racial integration. Much of the difficulty is that initial moves to more integrated settings are not sustained over time. Although the moves to integrated, sometimes suburban, neighborhoods seem to provide some evidence of more integrated settings for those who could lease up, the patterns for the sample as a whole are not different for experimental (MTO) and regular Section 8 movers. Moreover, although the patterns of the experimental and Section 8 movers are visually different from the control sample, they are not visually different from one another (Fig. 1). As for the discussion of access to low-poverty neighborhoods, the questions that are central to any conclusion about outcomes are (i) whether there are distinct gains from the experimental program (above those for regular Section 8 voucher holders), and (ii) how do the gains for the MTO group compare with the control group who did not receive help at all.

Fig. 1.

Current locations of households that moved. (Top) Regular Section 8 moves. (Middle) MTO moves. (Bottom) Control sample moves. Although the initial locations of the sample are distributed across a half-dozen central city tracts, for visualization purposes, they are shown as initiating from one central location.

By evaluating the current patterns of residences for experimental and Section 8 voucher holders (after any subsequent moves after the initial lease-up), we can evaluate the outcomes of the movement behaviors of the two groups. Experimental households who were able to find a unit in a low-poverty neighborhood are more dispersed and are somewhat more likely to live in suburban integrated neighborhoods (Fig. 1). There are significant numbers of MTO experimental movers in the western suburbs of Baltimore County, and there are many experimental voucher holders in the Baltimore City communities of Hamilton, Morgan Heights, and Lauraville (in the northeast sections of the city). Similar results are apparent in the report on the MTO program from Abt Associates (26). Regular Section 8 moves also are widely distributed in the western suburbs and in the northeast sections of the city. Visually the patterns are quite similar. Clearly, although the program had initial success, it is hard to sustain the patterns of dispersal.∥ Many more MTO households are now located in Baltimore City at the end of the evaluation period. We can infer a return to familiar neighborhoods in the city.**

The total MTO sample was comprised of self-selected households who expressed a desire to move. Thus, it is not surprising to find that members of the control group, who were not given vouchers, also had significant mobility. In the five-city study, the control group actually had higher mobility than did either the experimental participants or the regular Section 8 participants (26). Their geographic mobility also emphasizes the housing opportunities available to all households, experimental and nonexperimental. Although many households in the control group moved nearby, some households also were able to move to neighborhoods in the northeastern communities of Baltimore City and to the suburbs (Fig. 1). Still, the patterns are visually different from the experimental and Section 8 movers.

Table 3 shows that the initial moves of the MTO experimental group did result in greater integration. The pattern for Section 8 movers shows less overall integration but still some gains in living in less segregated settings. Examination of current residential locations for MTO movers, however, reveals that these gains have been eroded (Table 3). There is no significant difference between the current residence distribution for experimental movers and Section 8 movers. Both χ2 and Kolmogorov–Smirnov two-sample tests failed to detect any difference between the distributions of current residence locations for these groups. That the Section 8 and MTO distributions are not statistically different from each other suggests that, on the issue of racial integration, we must treat the gains from the experimental program with some caution. Although the distributions for Section 8 movers and experimental movers are significantly different from the control sample, overall the results reiterate the difficulty of intervening in residential choice. Mobility decisions are complex and are set within family, neighborhood, and work contexts.

Table 3. Move outcomes of MTO and Section 8 respondents by racial composition of the neighborhood.

| Initial move

|

Current location

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % black | MTO | Section 8 | MTO nonmover | MTO mover | Section 8 mover |

| 0—20 | 7.1 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 5.8 | 3.4 |

| 20—40 | 27.9 | 10.6 | 2.3 | 13.3 | 14.7 |

| 40—60 | 18.6 | 9.1 | 10.3 | 10.0 | 7.7 |

| 60—80 | 15.0 | 15.9 | 4.6 | 15.8 | 11.2 |

| 80—100 | 31.4 | 60.6 | 79.3 | 55.0 | 62.9 |

Source: MTO data for Baltimore prepared by HUD's Office of Policy Development and Research. Census data for both initial location and current (2002) location are from the 2000 Census.

Even without vouchers and the special counseling of the MTO program, the control-sample households moved away from housing projects in the inner city. Clearly, housing demolition in the central city displaced some of these households, and in this sense, they were forced movers. In the past decade, ≈1,000 public housing units have been removed in Baltimore, and some of the residents in these projects were part of the control group. Even so, insofar as many of them made choices that are not dissimilar to the assisted households raises questions about the policy effectiveness of the special subsidy MTO program.

Conclusion

Overall, it seems that the special MTO program, although partially successful and clearly an indication of HUD's concern to find mechanisms for diffusing the geographic concentration of minorities, also is a telling indication of how difficult it is to intervene in the complex process of housing choice. Income and assets are critical and integral parts of the choice process, as are neighborhood composition preferences. Simply providing a housing voucher does not negate the powerful forces of concerns with neighbors, friends, and access to work in the choice process. Nor does it negate a tendency, as we know from a large body of research on residential mobility, for households to move short distances and often to neighborhoods with which they are familiar. The evidence of return to known and familiar neighborhoods is an indicator of the way in which housing choices are embedded in the larger urban structure. There are data, too, that nonmovers also make gains. Nonmovers with more time in the community and the possibility of tapping into the opportunity structure of the neighborhood are actually likely to have higher employment rates than do movers (26). Perhaps unsurprisingly, moving is not a simple solution to problems of poor families, even though the overall picture suggests gains from movements out of poverty areas.

To reiterate, the increasing emphasis on geographically dispersing housing-subsidy recipients is based on the assumption that residence in concentrated poverty neighborhoods abets socially dysfunctional behavior, or more simply, that poverty households will do better outside of poverty neighborhoods. Although the tentative evidence points in this direction (i.e., overall, participating tenants do gain from the dispersed moves), the gains seem to come not from the lower concentration of poverty per se but from the “structural advantages of the suburban areas, such as schools, public services, and job accessibility” (13). Clearly, neighborhood effects, to the extent they exist, are complex and not easily transferred to in-movers. There are real questions about whether we can see neighborhoods themselves as socializing agents. Thus, the mere existence of a dispersed pattern of assisted households will not guarantee moves out of poverty or success in the labor market.

In the most recent presentation of the results from the five sample cities, the review of the MTO program tends to be favorable and positive. It is a natural response of the stakeholders to find that, in general, the MTO treatment led to significant differences in where families moved with the program vouchers (ref. 26, p. 46). The conclusion that the differences had narrowed only marginally over time may be an overly optimistic conclusion based on the research in this paper. Although the mobility patterns of the experimental families may have placed them in significantly better environments than those of the control group, the lack of differences between experimental and regular Section 8 movers at their current locations raises questions about the cost benefits of the intervention policy.

Acknowledgments

I thank Susan Hanson and Benjamin Forest for their comments on earlier drafts of the paper.

Author contributions: W.A.C. designed and performed research and wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: MTO, Moving to Opportunity; HUD, Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Footnotes

On the one hand, several studies (15–17) emphasize the impact of macroeconomic structural changes that have taken jobs away from the inner city and thus disadvantaged inner-city minority residents. On the other hand, there are studies that argue that the concentrations of poverty are the outcomes of historic patterns of discrimination, including the intentional citing of public housing in inner-city areas (18).

Nationally, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has funded ≈1.26 million public housing units, 1.4 million units in assisted housing programs, and 1.5 million households in the Housing Voucher Program (4).

The reports also have tended to aggregate data across the five cities rather than examining individual metropolitan outcomes.

“Lease up” is the terminology to describe the process of successfully using the housing voucher to rent a housing unit and move. The program was initiated and the sample selected in the period 1994–1997. To reiterate, there are three groups in the study: experimental movers who are given a housing voucher and special counseling, regular Section 8 movers who are given a housing voucher, and the baseline or control group who are not provided with assistance.

An interim analysis of the total MTO program suggested that MTO movers were staying in their new communities (30).

The data on actual origins and destinations of the moves were not made available for this analysis.

References

- 1.Dietz, R. (2002) Soc. Sci. Res. 31, 539-575. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ellen, I. G. & Turner, M. (1997) Housing Pol. Debate 8, 833-866. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agnew, J. A. & Duncan, J. S., eds. (1989) The Power of Place: Bringing Together Geographical and Sociological Imaginations (Unwin Hyman, Winchester, MA).

- 4.Devine, D., Gray, R., Rubin, L. & Taghavei, L. (2003) Housing Choice Voucher Location Patterns: Implications for Participant and Neighborhood Welfare (Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Washington, DC).

- 5.Clark, W. A. V. & Dieleman, F. (1996) Households and Housing: Choices and Outcomes in the Housing Market (Rutgers Univ. Press, Center for Urban Policy Research, New Brunswick, NJ).

- 6.Moore, E. G. & Clark, W. A. V. (1980) in Residential Mobility and Public Policy, eds. Moore, E. G. & Clark, W. A. V. (Sage, Beverly Hills, CA), pp. 10-28.

- 7.Duncan, G., Brooks-Gunn, J. & Klebanov, P. (1994) Child Dev. 65, 296-318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sampson, R., Raudenbush, S. & Earls, F. (1997) Science 277, 918-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pauleit, S. (2003) Built Environ. 29, 89-93. [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dam, F., Heins, S. & Elbersen, B. S. (2002) J. Rural Stud. 18, 461-476. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vries, S., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P. & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2003) Environ. Plann. A 35, 1717-1731. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Epstein, H. (Oct. 12, 2003) N.Y. Times Magazine, pp. 1-9.

- 13.Briggs, X. d. S. (1997) Housing Pol. Debate 8, 195-234; (1998) 9, 177-221. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massey, D. S., Gross, A. B. & Shibuya, K. (1994) Am. Sociol. Rev. 59, 425-445. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson, W. J. (1987) The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy (Univ. Chicago Press, Chicago).

- 16.Hughes, M. (1989) Econ. Geogr. 65, 187-207. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ihlandfeldt, K. & Sjoquist, D. (1998) Housing Pol. Debate 9, 849-892. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yinger, J. (1995) Closed Doors, Opportunities Lost (Russell Sage, New York).

- 19.Galster, G. & Zobel, A. (1998) Housing Stud. 13, 605-622. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen, Q. (2001) J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 67, 53-68. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goetz, E. (2004) Clearing the Way: Deconcentrating the Poor in Urban America (Urban Institute, Washington, DC).

- 22.Galster, G. (2003) Housing Stud. 18, 813-914. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenbaum, J. (1995) Housing Pol. Debate 6, 231-269; [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rosenbaum, J. & Harris, L. (2001) Housing Pol. Debate 12, 321-346. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hollman v. Cisneros, Civ. No. 4-92-712 (D. Minn. filed Apr. 21, 1995).

- 26.Orr, L., Feins, J., Jacob, R. & Beecroft, E. (2003) Moving to Opportunity, Interim Impacts Evaluation Final Report (Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research, Washington, DC).

- 27.Duncan, G., Clark-Kauffman, E. & Snell, E. (2004) Residential Mobility Interventions as Treatments for the Sequelae of Neighborhood Violence (Northwestern Univ., Chicago), www.northwestern.edu/ipr/publications/papers/2004/duncan/neighviolence.pdf.

- 28.Kling, J., Liebman, J., Katz, L. & Sanbonmatsu, L. (2004) Moving to Opportunity and Tranquility (Princeton Univ., Princeton), www.wws.princeton.edu/~chw/papers/Kling_mto481.pdf.

- 29.Tiebout, C. (1956) J. Pol. Econ. 64, 418-424. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goering, G., Feins, J. D. & Richardson, T. M. (2002) J. Housing Res. 13, 1-30. [Google Scholar]