Abstract

Aerosol mixing resulting from turbulent flows is thought to be an important mechanism of deposition in the upper respiratory tract (URT). Since turbulence levels are a function of gas density, the use of a low density carrier gas would be expected to reduce deposition in the URT. We measured aerosol deposition in the respiratory tract of 8 healthy subjects using both air and heliox, a low density gas mixture containing 80% helium and 20% oxygen, as the carrier gas. The subjects breathed 0.5, 1, and 2 μm-diameter monodisperse polystyrene latex particles from a reservoir at a constant flow rate (~450 mL/sec) and tidal volume (~900 mL). Aerosol concentration and flow rate were measured at the mouth using a photometer and a pneumotachograph, respectively. Deposition was 17.0%, 20.3%, and 38.9% in air and 16.8%, 18.5%, and 36.9% in heliox for 0.5, 1, and 2 μm-diameter particles, respectively. There was a small but statistically significant decrease in deposition when using heliox compared to air for 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles (p < 0.05). While it could not be directly measured from these data, it is likely that when breathing heliox instead of air, deposition is reduced in the URT and increased in the small airways and alveoli.

Keywords: turbulent mixing, helium, particles

INTRODUCTION

The penetration and subsequent deposition of inhaled particles in the human lung depends on both particle and gas flow characteristics. Particle characteristics include parameters such as shape, size and density. Gas flow is affected by the physical properties of the gas, and also by the breathing pattern and the branching structure of the respiratory tract. It is widely accepted that the mechanisms of inertial impaction, gravitational sedimentation, and Brownian diffusion mainly govern the deposition of aerosol particles in the lung. Inertial impaction is a velocity-dependent mechanism and causes most of the particles larger than ~5 μm to deposit in the upper respiratory tract (URT, which extends from the lips to the glottis) and in the first generations of the tracheobronchial tree. Brownian diffusion and gravitational sedimentation are time-dependent mechanisms. Brownian diffusion primarily affects small particles (<~0.5 μm). Sedimentation is the gravitational settling of particles and mainly affects particles in the size range 1–5 μm which deposit in the small airways and alveolar ducts. Therefore, high inspiratory flow rates (and correspondingly short breathing cycles) increase deposition by inertial impaction and decrease deposition by gravitational sedimentation and Brownian diffusion and vice-versa. High flows also generate turbulent mixing in the URT and first generations of conducting airways,1 which is thought to be a major factor in aerosol deposition in these regions.

There are two major mechanisms that are likely to affect deposition of 0.5–2 μm-diameter particles in the URT and first generations of conductive airways: inertial impaction and turbulent mixing. Deposition by inertial impaction results from particles deviating from the gas streamlines and depositing on airway walls. Such mechanism requires high speed flow but not necessarily a turbulent regime. Turbulent mixing refers to the irregular fluctuations or mixing undergone by the fluid in a turbulent regime. As a result, the speed and therefore the trajectories of particles are continuously undergoing changes in both magnitude and direction. Such changes may cause particles to deposit on airway walls. Turbulent flows can be described in terms of their mean values over which are superimposed the fluctuations. Deposition by inertial impaction will be affected by the mean flow while deposition due to turbulent mixing will be affected by the fluctuations.

Levels of turbulence in the respiratory tract are a function of gas density. Lowering the density of the inspired gas converts some or all of the turbulent flow into laminar flow. A mixture of 80% helium and 20% oxygen (heliox) has a gas density about one third that of air and a viscosity that is about 8% higher than that of air. Turbulent airflow in the URT and first generations of conducting airways, which is commonly present at normal breathing rates,2,3 is therefore reduced when breathing heliox instead of air. A reduction in turbulent mixing would be expected to also reduce deposition in the URT and first generations of conducting airways and allow for targeting aerosol in the more peripheral airways.

The effect of carrier gas on aerosol deposition in the respiratory system as a whole has produced conflicting results in previous studies. In healthy human subjects, some studies suggested a decrease or no change in deposition in heliox compared to air,4,5 while other studies showed an increased deposition in heliox.6,7 In the present study, in an attempt to clarify the issue, we measured the deposition of 0.5, 1, and 2 μm-diameter particles in the lung of eight healthy subjects using both air and heliox as carrier gas. Deposition was measured for the whole respiratory system with the same breathing protocol for air and heliox.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Equipment

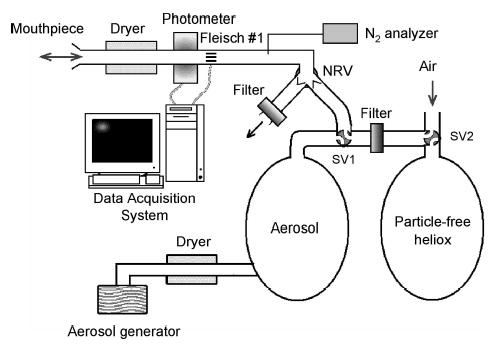

Deposition data were collected by using the equipment shown in Figure 1 which is similar to that used in a previous study.8 The subject breathed through a non-rebreathing valve (NRV). A three-way sliding valve (SV1) was connected to the inhalation port of the NRV, allowing the subject to breathe aerosol–free gas through a filter before the start of the experiment. An additional sliding valve (SV2) was connected to the other side of the filter to select between air and an aerosol-free mixture of 80% helium/20% oxygen, hereafter denoted heliox. The measurement of the aerosol concentration and the flow rate was provided by a photometer (model 993000, Pari)9 and a Validyne M-45 differential pressure transducer connected via short tubes to the two ports of a pneumotachograph (Fleisch no. 1, OEM Medical, Richmond, VA), respectively. A diffusion dryer was located between the photometer and the mouthpiece, adding ~10 mL to the deadspace of the breathing apparatus. The pneumotacho-graph and the photometer were heated to body temperature to prevent water condensation. The photometer was located close to the mouth so that any deposition in the experimental apparatus and/or delivery devices did not affect our measurements.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of experimental system. A two-way non-rebreathing valve (NRV) allows subject to inhale aerosol or particle-free gas mixture depending on the configuration of sliding valve SV1 and to exhale into room through a filter. An additional sliding valve SV2 allows for selection between room air and particle-free heliox. Compressed gas used for generating aerosol is either air or heliox depending on experiment. Measurement of aerosol concentration and flow rate is provided by a photometer and a pneumotachograph (Fleisch no. 1), respectively.

Aerosol generation

The aerosol reservoir was filled with monodis-perse polystyrene latex particles (Duke Scientific). The particles were supplied in aqueous suspensions at 10% solid by weight with a trace amount of surfactant to inhibit agglomeration and promote stability. The aqueous suspensions were diluted with deionized water before being dispensed via two Acorn II nebulizers (Marquest Medical Products).

Depending on the test performed, the compressed gas used to aerosolize the particles was medical air or heliox. Before entering the reservoir, the aerosol flowed through a heated hose and a diffusion dryer to remove water droplets so that the resulting aerosol was made of dry latex particles of uniform size. The following particle sizes, as provided by the manufacturer, were used in the study: 0.505 ± 0.0096, 1.03 ± 0.022, 2.02 ± 0.063 (SD) μm. For convenience, these are referred to as 0.5, 1, and 2 μm-diameter particles, respectively. The aerosol concentration were ~104 particles/ml of gas for 0.5 and 1 μm-diameter particles and ~5 ×103 particles/ml of gas for 2 μm-diameter particles. Previous size analysis10 have shown that the number of doublets in the aerosol was <3% for 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles and <4.5% for 0.5 μm-diameter particles.

Hygroscopic growth of surfactant residues

Surfactant residues have the potential to impact the photometer response compared to the signal generated by the latex particles in use. During inspiration, when the gas is dry, because of their small size, they are likely not detected by the photometer. During expiration, however, the residues can contribute to the photometer signal if they are hygroscopic and have grown to a size detectable by the photometer. The residues were present in both cases (air and heliox) and the phenomenon of hygroscopic growth likely occurred in both cases. However, because of the different thermal properties of the two test atmospheres, the growth in air was smaller than in heliox.

Indeed, the conditioning of the respired gas is governed by the principles of heat and water exchange. Such exchange is affected by the thermal properties of the respired gas mixture as well as by the diffusive properties of water vapor in the gas mixture. The specific heat of heliox is about four times higher than the specific heat of air.11 Water vapor diffuses about twice as fast in heliox than in air.12,13 Both of these properties result in a greater hygroscopic growth in heliox than in air. The data suggest that the surfactant residue grew to a size detectable by the photometer when he-liox was breathed. In air, the growth was such that the increase could not be detected by the photometer. Therefore, to permit correct measurements of aerosol concentration in both test atmospheres, adequate drying of the aerosol during expiration was ensured by heating the dryer located between the mouthpiece and the photometer. When heated to ~30°C, there was no detectable signal from surfactant residues.

In addition to the presence of surfactant residues in the test atmospheres, surfactant may also be present on the particles themselves. As a result, Gebhart et al.14 noted that the particles take up a thin sheet of water inside the respiratory tract. These observations were made while breathing air. Because of the different thermal properties of the two test atmospheres, it is reasonable to wonder if a thicker layer of water might result while breathing heliox. If this is the case, the size of the particles in the respiratory tract while breathing heliox would be larger than during air breathing. The result of this would be a higher deposition in heliox than in air from particle size considerations alone. As we cannot directly test this in these experiments, our data in heliox can be viewed as an upper bound for deposition.

Data recording and analysis

A PC (IBM ThinkPad 360 CSE) equipped with a 12-bit analog-to-digital card (National Instruments, DAQ700) was used for data acquisition. Signals from the photometer and the pneumota-chograph were sampled at 100 Hz. We used the same custom software for the data acquisition developed in a previous study by our group.8

Subjects and protocol

Eight healthy subjects participated in the study. Their relevant anthropometric data are listed in Table 1. Subjects 1–4 were the same subjects that participated in previous studies of aerosol deposition.8 Tests were performed with two test atmospheres: air and heliox. Subjects were asked to breathe through the mouthpiece at a constant flow rate (458 ± 50 mL/sec) and tidal volume (918 ± 97 mL) over a period of 5 min. A flowmeter provided feedback to the subject, and an audible metronome was used to maintain a constant breathing frequency. Subjects inhaled from the aerosol reservoir and exhaled into the room through a filter. When tests were performed with heliox, prior to the start of the test, the subjects were asked to perform several vital capacity maneuvers inhaling from the reservoir filled with particle-free heliox. In this manner, the lungs were washed in with the test gases. The wash-in was monitored by a nitrogen analyzer measuring the concentration of nitrogen in the exhaled gases and the protocol began when expired nitrogen concentration was less than 10%. Prior to each experiment, flow calibration was performed with the test gases (air or heliox) using a 3-L calibration syringe. Therefore no correction of the flow signal was required in the data analysis. The protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Program at the University of California, San Diego and subjects signed a statement of informed consent.

Table 1.

Anthropometric Data

| Subject no. | Gender | Age, years | Height, cm | Weight, kg | FVC, %pred | FEV1/FVC, %pred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 35 | 165 | 57 | 117 | 96 |

| 2 | F | 32 | 163 | 67 | 105 | 100 |

| 3 | M | 53 | 190 | 99 | 131 | 102 |

| 4 | M | 45 | 185 | 116 | 104 | 106 |

| 5 | M | 32 | 180 | 74 | 101 | 98 |

| 6 | M | 33 | 188 | 110 | 91 | 93 |

| 7 | M | 36 | 185 | 100 | 114 | 77 |

| 8 | F | 39 | 175 | 82 | 89 | 107 |

F, female; M, male; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory capacity in 1 sec; %pred, % predicted.

Data analysis

We used the same analysis as in a previous study by our group.8 For each breath, total deposition (DE) was calculating using the following equation

| (1) |

where Nin and Nex are the number of inspired and expired particles, and Vin and Vex are the inspired and expired volumes, respectively. Only the breaths where Vin and Vex differed by less than 3% were considered in the analysis. The first three to six breaths of the test were aerosol wash-in and were discarded in the calculation of steady state deposition.

Based on our raw data, inhaled aerosol concentrations varied by less than 15% between tests performed in air and in heliox. As deposition was determined by the difference between the number of inspired (Nin) and expired particles (Nex) for each breath, the measurement was independent of the exact number of particles entering the lung. Therefore the small difference in inhaled aerosol concentrations between air and heliox did not affect the measurements.

Statistical analysis was performed by using Systat V5.03 (Systat, Evanston, IL). Data were grouped in three categorical variables: test atmosphere (air and heliox), particle size (0.5, 1, and 2 μm), and subject (1–8). A two-way analysis of variance in which subjects acted as their own controls was then performed to test for differences between the chosen categorical variables. Post hoc testing using Bonferroni adjustment was performed for tests showing significant F-ratios. Significant differences were accepted at the p < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

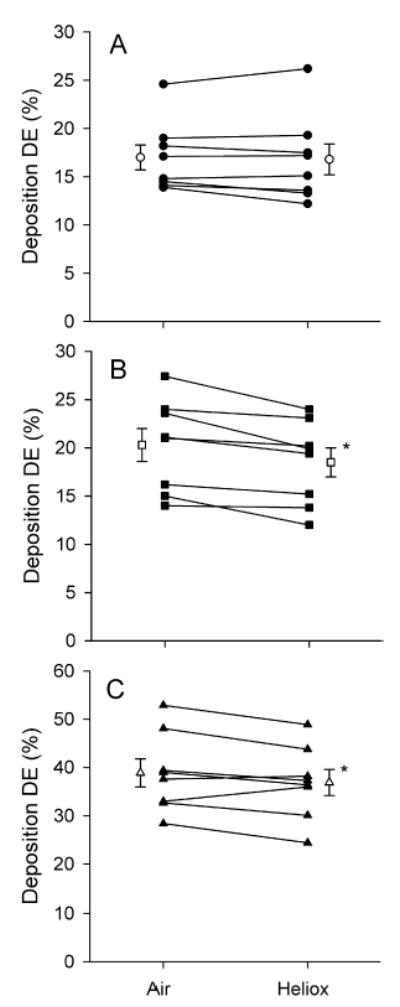

The effect of the carrier gas on aerosol deposition is shown in Figure 2 for 0.5, 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles. For each particle size, deposition is plotted as a function of the carrier gas. Deposition averaged over the eight subjects (mean ± SE, open symbols) is shown as well as individual data (closed symbols), the latter data illustrating intersubject variability. Deposition was size dependent and ranged from 17.0% to 38.9% in air and from 16.8% to 36.9% in heliox. Differences in deposition between air and heliox were small for each particle size, although, for 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles, difference was significant (P < 0.05) with deposition being lower in heliox than in air.

FIG. 2.

Total deposition (DE) of aerosol particles as a function of gas mixture. Individual data are shown by closed symbols. Total deposition averaged over eight subjects (mean ± SE) is shown by open symbols. *Significantly different from deposition in air (p < 0.05). (A) dp = 0.5 μm. (B) dp = 1 μm. (C) dp = 2 μm.

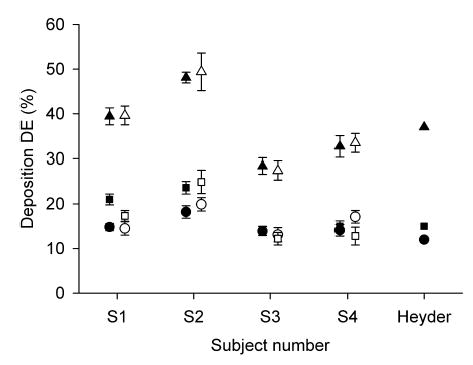

Figure 3 compares total deposition values obtained with air in this study (closed symbols) and in a previous study (open symbols) by our group8 in which subjects 1–4 also participated. Deposition data are shown for each of these four subjects separately. They are represented by their mean and SD. In both studies, data were obtained with air for a flow rate of ~450 mL/sec and a breathing frequency of ~15 min−1. For the purpose of clarity, the two sets of data were slightly shifted apart. There was no significant difference between deposition in air measured in both studies. Our data were also compared to that obtained by Heyder et al.15 in three healthy subjects for a tidal volume of 1000 mL and a flow rate of 500 mL/sec. Heyder’s data are displayed on the right side of Figure 3.

FIG. 3.

Total deposition of aerosol particles in air as a function of subject number. Closed and open symbols represent individual data from the present study and from a previous study by our group in which subject 1–4 also participated.8 Data from Heyder et al.15 are also shown on the right side of the figure for a tidal volume of 1000 mL and a flow rate of 500 mL/sec. • and ○, dp = 0.5 μm; ▪ and □, dp = 1 μm; ▴ and ▵, dp = 2 μm.

DISCUSSION

The main goal of this study was to determine the effect of the carrier gas on aerosol transport and deposition in the human lung. Tests were performed at a constant flow rate of ~450 mL/sec for which turbulent flow would be generated in the URT when breathing air but not when breathing heliox. Flow regime is usually characterized by the Reynolds’number, Re. In the upper airways, Re is the highest at the level of the glottic constriction where the airstream is accelerated. For a flow rate of 450 mL/sec, Reglottis is ~3500 for air and ~1100 for heliox. In a cylindrical airway, flow is considered laminar when Re < 2100. However, because of the sudden constriction of the air passage at the level of the glottis, local turbulence has been observed for Re < 2100.1 We therefore chose a flow rate that would generate a Reynolds’ number that was low enough to minimize local turbulence at the glottis when breathing heliox.

For particles in the diameter range 0.5–2 μm, Figure 2 shows that there was a difference in deposition between air and heliox. While small, the difference was however significant for 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles with deposition being lower in heliox than in air. All eight subjects showed a reduction in deposition for 1 μm-diameter particles and six out of eight subjects for 2 μm-diameter particles. These results are in agreement with a theoretical analysis by Hamill16 on the effect of turbulent diffusion on particle deposition in the upper respiratory system. The author showed that, while negligible for 0.5 μm-diameter particles, deposition by turbulent mixing increased with increasing particle size and became the dominant deposition mechanism for 5 μm particles. Therefore, reducing the level of turbulence in the upper respiratory tract would be expected to reduce deposition of large particles more than that of small particles.

Prior to inhaling particles, the subjects performed vital capacity maneuvers when breathing heliox and not when breathing air. This difference in protocol is unlikely to have affected the measurements. In a study by Jensen et al.,17 where airway resistance was used as an index of net airway caliber, the authors showed that, compared to tidal breathing, healthy subjects showed dilation of their airways during a deep inspiration to total lung capacity. However, this airway dilation returned to baseline after about three normal breaths post-deep inspiration. In our protocol, subjects were breathing aerosol over a period of 5 minutes and the first three to six normal breaths were discarded in the calculation of steady state deposition. Therefore, it is likely that the vital capacity maneuvers did not affect our measurements in heliox.

We compared deposition data of subjects 1–4 with those from a previous study8 in which they also participated and where deposition of 0.5, 1, and 2 μm-diameter was measured while breathing air. Deposition was computed in the same manner in both studies. Data are shown on Figure 3 and show good agreement. Thus we are confident that they were no systematic differences in our data introduced by the modifications made to the system between the two studies. Furthermore, our data are compared with data previously obtained by Heyder et al.15 for a similar breathing protocol and also show good agreement.

Several studies looking at the effect of the carrier gas on aerosol deposition have been reported in the literature.4–7,18–20 While differences in experimental protocols make a direct comparison difficult, it is worth highlighting some of the similarities and differences between the results of these studies. Studies by Svartengren et al.4 and Anderson et al.5 were performed in healthy human subjects with 3.6 μm-diameter Teflon particles labeled with 99mTc. Subjects performed eight to twelve deep inhalations breathing particles suspended in air or heliox. In the study by An-derson et al.,5 each inspiration was followed by a breath hold of one to two seconds but there was no such breath hold in the study by Svartengren et al.4 Svartengren et al.4 showed that while there was a trend for deposition in the throat and mouth to be less when breathing heliox than when breathing air (17% versus 27%, p > 0.05), there was no difference in alveolar deposition between the two gas mixtures. Anderson et al.5 found a significantly lower deposition in the mouth and throat when breathing heliox than when breathing air but a higher alveolar deposition in heliox than in air. The difference in alveolar deposition between the two studies is more likely due to additional particle deposition occurring during the one to two seconds breath hold following each inspiration in Anderson et al.’s study. Indeed, a lower deposition in the URT when breathing heliox allows for a larger number of particles to penetrate and deposit in the more distal region of the lung. Our data do not allow us to distinguish between deposition in the URT, in the conducting airways and in the alveolar region of the lung. However, based on the results of Svartengren et al.4 and Anderson et al.,5 it is very likely that the decrease we observed in deposition between air and heliox resulted from a decrease in deposition in the URT that was larger than the increase in alveolar deposition if indeed such an increase occurred.

Kleinstreuer et al.21 performed computer simulations of aerosol transport in a URT model that included the trachea, using a low-Reynolds number (LRN) turbulence model that has been shown to best capture transitional to turbulent flows such as those present in the human lung.22 Their simulations clearly predicted the onset of turbulence after the glottic constriction for inspiratory flow rates varying from quiet breathing (250 mL/sec) to exercise breathing (1000 ml/s). Their simulations also suggest a higher deposition in the URT for higher Reynolds’s number, most likely because higher Re generate higher intensities of turbulence. A recent numerical study by Gemci et al.23 looking at aerosol drug deposition in the throat also suggested that the use of heliox leads to less particle deposition in the extratho-racic region of the respiratory tract. Both numerical studies agree with the experimental observations of a lower URT deposition in heliox than in air.4,5

Esch et al.6 measured deposition after one single breath for particles suspended in air, heliox, and a high density mixture of SF6 and O2. Tests were performed in four healthy human subjects and in excised human and canine lungs. While there was no significant difference in deposition between gas mixtures in the dog lungs, there was significantly greater particle deposition from he-liox and less deposition from SF6-O2 mixture compared to air in human lungs, with no difference between the in vivo and excised lungs. The authors argued that the major reason for inter-species difference in deposition was the difference in lung morphology between the dog and the human lung, the more symmetric branching structure in the human lung causing more flow rearrangement at each bifurcation than in the monopodal canine lung. The deposition data obtained in the human lungs by Esch et al.6 are in contradiction with our data where deposition was lower in heliox than in air. We determined deposition during steady-state tidal breathing while Esch et al. calculated deposition from a single inhalation/exhalation of particles with the exhalation volume being twice the inhalation volume. Such a large exhalation volume allows for probing deposition in the more distal region of the lung where a larger number of particles would be expected to penetrate and deposit when breathing heliox than when breathing air. It is likely that the difference in deposition between the two studies results primarily from the difference in breathing maneuvers.

Swift et al.7 also found a higher deposition in heliox than in air during tidal mouth breathing in normal human subjects using 1.7-μm-diameter particles. A tyndallometer was used for aerosol concentration measurements and was separated from the mouthpiece by a pneumota-chograph. Therefore, aerosol deposition values in the Swift et al.7 study not only reflect deposition in the lung but also deposition that occurred in the pneumotachograph during tidal breathing. It is likely that the error induced by the presence of the pneumotachograph varied with each experimental condition; however the extent of this error is difficult to predict with the data available to us. In our study, the photometer was connected directly to the mouthpiece unit to avoid such an error on the determination of aerosol deposition in the lung. It should also be noted that only two subjects participated in Swift et al.7 study. Our data showed that, while for most of the subjects deposition of 2-μm-diameter particles was lower in heliox than in air, two of the subjects exhibited the opposite trend with deposition being higher in heliox than in air. Thus, conclusions drawn for only two subjects may not be totally reliable.

In conclusion, our data showed a small but significant decrease in deposition in heliox compared to air for 1 and 2 μm-diameter particles. While it cannot be directly measured from these data, other experimental4,5 and numerical21,23 studies strongly suggest that the location of deposited aerosol in the respiratory tract was more peripheral when breathing heliox than air. Indeed, one would expect that the low density of heliox would reduce deposition in the URT and first generations of conducting airways and allow for a larger number of particles to penetrate to the more peripheral regions of the lung where they eventually deposit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. W.G. Kreyling from the GSF institute for Inhalation Biology in Munich, Ger-many, for his technical advice and fruitful discussion. This work was supported by a research grant from the Academic Senate of the University of California, San Diego, and by NIH grant 1 RO1 ES11184–01A1.

References

- 1.Ultman, J. 1985. Gas transport in the conducting airways. In L.A. Engel and M. Paiva, eds. Gas Mixing and Distribution in the Lung. M. Dekker, New York, 63–136.

- 2.West JB, Hugh-Jones P. Patterns of gas flow in the upper-bronchial tree. J Appl Physiol. 1959;14:753–759. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1959.14.5.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dekker E. Transition between laminar and turbulent flow in human trachea. J Appl Physiol. 1961;16:1060–1064. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.6.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svartengren M, Anderson M, Philipson K, et al. Human lung deposition of particles suspended in air or in helium/oxygen mixtures. Exp Lung Res. 1989;15:575–585. doi: 10.3109/01902148909069619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson M, Svartengren M, Philipson K, et al. Deposition in man of particles inhaled in air or helium-oxygen at different flow rates. J Aerosol Med. 1990;3:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esch JL, Spektor DM, Lippmann M. Effect of lung airway branching pattern and gas composition on particle deposition. II Experimental studies in human and canine lungs. Exp Lung Res. 1988;14:321–348. doi: 10.3109/01902148809087812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swift DL, Carpin JC, Mitzner W. Pulmonary penetration and deposition of aerosols in different gases: fluid flow effects. Ann Occup Hyg. 1982;26:109–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darquenne C, Paiva M, West JB, et al. Effect of microgravity and hypergravity on deposition of 0.5- to 3-μm-diameter aerosol in the human lung. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:2029–2036. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.6.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Westenberger S, Gebhart J, Jaser S, et al. A novel device for the generation and recording of aerosol micro-pulses in lung diagnostic. J Aerosol Sci. 1992;23:S449–S452. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darquenne C, West JB, Prisk GK. Dispersion of 0.5–2 μm aerosol in micro- and hyper-gravity as a probe of convective inhomogeneity in the human lung. J Appl Physiol. 1999;86:1402–1409. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.86.4.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clarkson DP, Schatte CL, Jordan JP. Thermal neutral temperature of rats in helium-oxygen, argon-oxygen, and air. Am J Physiol. 1972;222:1494– 1498. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1972.222.6.1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paganelli CV, Kurata FK. Diffusion of water vapor in binary and ternary gas mixtures at increased pressures. Respir Physiol. 1977;30:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(77)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang, H.K. 1985. General concepts of molecular diffusion. In L.A. Engel, and M. Paiva, eds. Gas Mixing and Distribution in the Lung. M. Dekker, New York, 1–22.

- 14.Gebhart J, Heigwer G, Heyder J, et al. The use of light scattering photometry in aerosol medicine. J Aerosol Med. 1998;1:89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heyder J, Gebhart J, Rudolf G, et al. Deposition of particles in the human respiratory tract in the size range 0.0005–15 μm. J Aerosol Sci. 1986;17:811–825. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamill P. Particle deposition due to turbulent diffusion in the upper respiratory system. Health Physics. 1979;36:355–369. doi: 10.1097/00004032-197903000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen A, Atileh H, Suki B, et al. Signal trans-duction in smooth muscle Selected Contribution: Airway caliber in healthy and asthmatic subjects: effects of bronchial challenge and deep inspirations. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:506–515. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.1.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson M, Svartengren M, Bylin G, et al. Deposition in asthmatics of particles inhaled in air or in helium-oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;147:524–528. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/147.3.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulz H, Schulz A, Eder G, et al. Influence of gas composition on convective and diffusive intrapul-monary gas transport. Exp Lung Res. 1995;21:853–876. doi: 10.3109/01902149509031767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Svartengren M, Skogward P, Nerbrink O, et al. Regional deposition of inhaled Evans blue dye in mechanically ventilated rabbits with air or helium oxygen mixture. Exp Lung Res. 1998;24:159–172. doi: 10.3109/01902149809099580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinstreuer C, Zhang Z. Laminar-to-turbulent fluid-particle flows in a human airway model. Int J Multiphase Flow. 2003;29:271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z, Kleinstreuer C. Low-Reynolds-number turbulent flows in locally constricted conduits: a comparison study. AIAA J. 2003;41:831–840. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gemci T, Shortall B, Allen GM, et al. A CFD study of the throat during aerosol drug delivery using heliox and air. J Aerosol Sci. 2003;34:1175–1192. [Google Scholar]