Abstract

Glycogenin is a glycosyltransferase that functions as the autocatalytic initiator for the synthesis of glycogen in eukaryotic organisms. Prior structural work identified determinants responsible for the recognition and binding of UDP-glucose and the catalytic manganese ion and implicated two aspartic acid residues in the reaction mechanism for self-glucosylation. We examined the effects of substituting asparagine and serine for the aspartic acid residues at positions 159 and 162. We also examined whether the truncation of the protein at residue 270 (Δ270) was compatible with its structural integrity and its functional role as the initiator for glycogen synthesis. The truncated form of the enzyme was indistinguishable from the wild-type enzyme by all measures of activity and could support glycogen accumulation in a glycogenin-deficient yeast strain. Substitution of aspartate 159 by either serine or asparagine eliminated self-glucosylation, reduced trans-glucosylation activity by at least 260-fold but only reduced UDP-glucose hydrolytic activity by 4 to 14-fold. Substitution of aspartate 162 by either serine or asparagine eliminated self-glucosylation activity and reduced UDP-glucose hydrolytic activity by at least 190-fold. The trans-glucosylation of maltose was reduced to undetectable levels in the asparagine 162 mutant, while the serine 162 enzyme showed only a 18 to 30-fold reduction in its ability to trans-glucosylate maltose. These data support a role for aspartate 162 in the chemical step for the glucosyltransferase reaction and a role for aspartate 159 in binding and activating the acceptor molecule.

INTRODUCTION

Within a cell, glycogen functions as a reserve of glucose when metabolic demand for glucose outpaces the cell’s ability to obtain it from extracellular sources (1). Glycogen itself is a branched polymer of glucose composed of a series of α-1,4-glycosidic linkages with branch points occurring, on average, every ten to thirteen glucose residues through the formation of α-1,6-glycosidic linkages (1). The synthesis of glycogen is similar to that of other complex biologic polymers in that its synthesis has distinct initiation and elongation stages. The elongation stage of glycogen synthesis is catalyzed by glycogen synthase in concert with the branching enzyme. The initiation stage of glycogen synthesis is catalyzed in an autocatalytic manner by glycogenin (2,3).

The reaction catalyzed by glycogenin can be defined as autocatalytic, in that a solution of glycogenin, in the presence of UDP-glucose and Mn2+ cations, will catalyze the formation of short glucose polymers covalently attached to a tyrosine hydroxyl group on the surface of the enzyme (4). The site of attachment has been identified as Tyr194 in mammalian muscle forms of glycogenin (5). Expression of glycogenin in E. coli defective in UDP-glucose production yields glycogenin devoid of covalently attached glucose (6, J. Zhou, unpublished), while addition of UDP-glucose to such a glycogenin preparation or expression of glycogenin in E. coli competent for UDP-glucose production yields a population of glycogenin molecules with differing lengths of covalently attached glucosyl chains. Glycogenin continues to transfer glucose residues to this growing nascent glycogen chain until the chain length approaches ~10 residues, past which the efficiency of transfer decreases (4,7–8).

Glycogenin-like molecules have been found in organisms as diverse as yeast and humans (4). A study of the conserved residues based on these sequences has identified seven regions of conserved sequence, or sequence domains (4). However, only the first four sequence domains are found easily by sequence alignment in most of the known glycogenins. In terms of catalytically functional amino acids, there are relatively few universally conserved residues. Within domain I, a conserved Tyr occurs at the position homologous to residue 14 in rabbit muscle glycogenin. Within domain II, conserved Arg and Lys residues occur at positions 75 and 85, respectively. The DxD motif that is conserved throughout much of the glycosyltransferase family occurs at positions 100–102. Domain III contains a conserved Asn at position 132, conserved acidic residues at 159 and 162 and a conserved Gln residue at 163. Within conserved sequence domain IV, conserved His, Lys and Trp occur at positions 211, 217 and 219, respectively. Experiments performed with both the yeast and mammalian forms of glycogenin show that the concensus sequence “W-E-(X)n-D-Y-L” in sequence domain VII is involved in interactions with glycogen synthase and would appear to facilitate bulk glycogen synthesis by directly associating the priming enzyme with the major synthetic enzyme (9). Previous mutagenesis has demonstrated that the conserved Lys within conserved domain II is catalytically essential (10). Tyr194, while necessary for self-glucosylation (11), it is not catalytically essential such that a Phe194 mutant enzyme can glucosylsate, in trans, alternate acceptor molecules (12) and glycogenin subunits that retain Tyr194 (10).

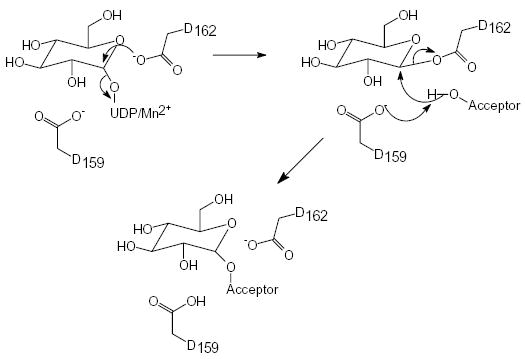

Glycogenin is a member of the glycosyltransferase family 8, a diverse set of glycosyltransferases, which includes among other enzymes, lipopolysaccharide glucosyltransferases. Eight distinct members of the glycosyltransferase superfamily have had their three-dimensional structures solved (13–20). These glycosyl-transferases share a similar nucleotide-binding fold of approximately 120 residues comprising a four-stranded α + β domain that is responsible for the majority of the interactions with the UDP moiety (21,22). In contrast, the remainder of the structures is fairly dissimilar, undoubtedly reflecting their differences in catalytic chemistry, nucleotide-sugar and acceptor molecule specificities. Four of these structures belong to the inverting class of glycosyltransferases and are expected to differ from glycogenin in their chemical and catalytic properties. However, four structures belong to the retaining class of glycosyltransferases and are expected to utilize common catalytic strategies and, therefore, active site residues. Similar to what has been shown for retaining glycosidases (23,24), retaining glycosyl-transferases may follow a two-step catalytic strategy involving a covalent enzyme-substrate intermediate with inverted stereochemistry, followed by a second attack at the C1 atom of the sugar ring that yields the final product and retention of configuration (Scheme 1). However, conflicting data exist as to the identity of the catalytic nucleophile in these structures.

Scheme 1.

In this study we sought to examine the catalytic contributions of two key residues within the substrate binding and active sites of rabbit glycogenin previously identified from structural analyses as potential catalytic residues. Specifically, the catalytic contributions of Asp159 and Asp162 were assessed by site-directed mutagenesis, as well as the functional consequences of truncation of the polypeptide chain at residue 270. We report here the characterization of these mutant enzymes by both steady-state kinetics and direct structure determination and compare the results with those of the wild-type enzyme.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutagenesis, Expression and Purification

All mutants were generated using the QuickChange Kit (Stratagene) and in all cases, prior to expression and purification, the complete coding region was resequenced to confirm that only the desired mutation(s) were incorporated. The Δ270 construct was created through the introduction of two consecutive stop codons at positions 271 and 272 of the wild-type rabbit muscle glycogenin cDNA, thereby eliminating the C-terminal 63 amino acids. Recombinant 6xHis-tagged glycogenin was purified using previously published procedures (10). Briefly, BL21 (DE3) cells transformed with the appropriate pET-28a plasmid were grown at 37°C until the cells reached an optical density of 0.7 at 600 nm, at which time isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to a final concentration of 0.4 mM. The cells were then grown at 30°C for an additional 4 hours. Alternatively, following induction of gene expression by IPTG, the incubation temperature can be reduced to 18°C and the cells are allowed to grow for an additional 16 hours. The bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspeneded in 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 1mM Na-EDTA, 1 mM Benzamidine and 1 mM DTT. Lysis of the cell suspensions was performed using a French Press operated at 1000 psi. A high speed supernatant was obtained by centrifugation and this material was loaded onto a Ni-NTA column (Qiagen) and washed to base line with 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM Na-EDTA and 1 mM Benzamidine. The protein was eluted from the column, following an initial wash with column buffer containing 10 mM Imidazole, with column buffer containing 50 mM Imidazole. The Δ270 protein did not require additional purification. For crystallography and detailed assays on the wild-type glucosylated enzyme and the 159S, 159N, 162S and 162N mutant enzymes, further purification utilizing a Q-Sepharose column was performed. The protein eluted from the Ni-NTA column was buffer exchanged into 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM Benzamidine and 1 mM Na-EDTA and applied to the Q-Sepharose column. The column was washed to baseline with the above buffer and then the bound protein was eluted using a linear gradient from 0–0.5M NaCl in a volume equal to 20 column volumes. Purity was monitored using SDS-PAGE analysis. For crystallization, the protein eluted from the Q-Sepharose column was buffer exchanged into 15 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT and concentrated to 9 mg/ml.

Molecular Mass Determination by Gel Filtration

Estimates for the solution molecular mass for the glycogenin enzymes were determined on a Pharmacia Superose-12 column equilibrated in phosphate-buffered saline. All enzymes were concentrated to between 1.5 and 1.8 mg/ml (17–20 μM). A total volume of 0.2 ml (3–3.6 μg) was injected onto the 24 ml column operated at 0.3 ml/min for analysis. The column was standardized using Blue Dextran, aldolase (158,000 daltons), albumin (67,000 daltons), ovalbumin (43,000 daltons), chymotrypsin (25,000 daltons) and ribonuclease (13,700 daltons).

Enzymatic Assays

The ability of wild-type and mutated glycogenins to catalyze self-glucosylation was assessed using an assay containing 0.6 to 1.8 μM enzyme in 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM MnCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 30 uM UDP-[U-14C]glucose in a total volume of 10 μL which was incubated for either 1 or 2.5 minutes at 30°C. Assays in which the concentration of UDP-glucose was increased (50–515 μM) were modified by the addition of cold UDP-glucose to the reaction mix and quantitated after accounting for the altered specific activity of the substrate. An aliquot (5 μl) removed from the reaction was spotted onto P81 chromatography paper which was then washed three times (30 minutes each wash) in 0.5% phosphoric acid and once in ethanol. The dried paper was counted in a liquid scintillation counter. The ability of wild-type and mutated glycogenins to catalyze the transfer of glucose to the alternate acceptor, maltose, was determined by incubating glycogenin (1 to 4 μM) for 2.5 min at 30°C in 50 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM MnCl2, 2 mM dithiothreitol, and 30 μM UDP-[U-14C]glucose containing 50 mM maltose (Sigma) as the glucose acceptor in a total volume of 10 μl. The reaction was terminated by the addition of a final concentration of 20 mM Na-EDTA. An aliquot (5 μl) of the reaction mixture was then spotted on silica gel thin layer plates (Whatman PE SIL/G UV) and subjected to ascending chromatography in a mobile phase containing acetonitrile:acetic acid:ethanol:water in the ratio 65:5:10:20. The plate is then dried and subjected to autoradiography. Quantitation of the individual reaction species was performed by excising the radioactive products from the TLC plate, followed by scintillation measurements of the excised species. A similar assay procedure and mixture, but without added maltose, was utilized to assess the ability of the purified glycogenin enzymes to catalyze the non-productive hydrolysis of UDP-glucose to free glucose and UDP.

Glycogen accumulation in S. cerevisiae

The 194F mutant form of human glycogenin-1 was modified with an N-terminal Flag-tag for monitoring protein expression level and subcloned into the yeast expression plasmid p425Gal1 (25). The Δ271-103A mutant form of human glycogenin-1 was constructed by a combination of site-directed mutagenesis to produce the 103A mutation and restriction digestion with Nde I to truncate the cDNA at codon position 271. The resulting construct was then modified with an N-terminal V5-tag for monitoring protein expression level and subcloned into the yeast expression plasmid p426GPD (23). Wild-type human glycogenin-1 was subcloned into the p426GPD plasmid to use as a complementation control. Coexpression from doubly transformed cells could then be obtained using a yeast strain that required functional selection for both Leu+ and Ura+. Such a glg1glg2 yeast strain was prepared in the following manner. GLG1 and GLG2 were disrupted with the TRP1 gene using a PCR-based strategy. PCR was carried out with primers using pRS304 (26) as template to create fragments that had the TRP1 gene flanked by 45 nucleotides of GLG1 or GLG2. The PCR products were transformed into yeast to create the strains with the desired gene disruptions. JZ2-a (MATα trp1 leu2 ura3-52 glg1-2::TRP1) was derived from EG328-1A (MATα trp1 leu2 ura3-52) by disrupting GLG1. JZ2-b (MATa trp1 thr4 ura-52 glg2::TRP1) was derived from DH4-101 (MATa trp1 thr4 ura-52) by disrupting GLG2. JZ2-a and JZ2-b mating created the diploid JZ5-a (MATa/α trp1/trp1 LEU2/leu2 thr4/THR4 ura3-52/ura3-52 GLG1-2/glg1-2::TRP1 glg2::TRP1/GLG2). JZ3-a (MATα trp1 leu2 ura3-52 glg1-2::TRP1 glg2::TRP1) and JZ3-b (MATa trp1 leu2 ura3-52 glg1-2::TRP1 glg2::TRP1) were derived from the dissection of JZ5-a. JZ4-a (MATa/α trp1/trp1 leu2/leu2 ura3-52/ura3-52 glg1-2::TRP1/glg1-2::TRP1 glg2::TRP1/glg2::TRP1) was a diploid generated by crossing JZ3-a and JZ3-b. JZ4-a was transformed with either p425Gal1-194F glycogenin, p426GPD-Δ272-103A glycogenin, or both plasmids using the lithium acetate method (27) and the transformed cells were grown on the appropriate selective plates at 30°C for 2–3 days prior to spotting onto selective plates and further incubated for 2 days at 30°C. Yeast colonies were exposed to iodine vapor to 2–3 minutes to monitor the level of glycogen accumulation (28). JZ4-a transformed with p426GPD containing the wild-type human glycogenin-1 gene was used as a positive control for glycogen accumulation.

Crystallization and Structure Determination

The Δ270 enzyme crystallizes at 7.5 mg/ml from solutions containing 1 mM UDP-glucose, 1 mM MnCl2, 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5–4.7 and 10–13% (w/v) PEG 4000 in the space group P64, with cell dimensions a=b=75.0, c=233.4, γ =120° and a dimer in the asymmetric unit. The resulting unit cell is pseudo-P6422, with the ncs-dimer axis equivalent to the crystallographic two-fold. The decision as to which cell is correct was based on both analysis of the raw data as well as refinements in both cells. The raw data processed marginally better in the lower symmetry cell (overall merging R-values were 0.5% lower and 5% lower in the highest shell). However, the most compelling difference was that the final refined model possessed a Rfree value that was 3% lower overall in the P64 cell. The full-length 159S, 159N, and 162S mutant glycogenin enzymes crystallize at 8 mg/ml from solutions containing 11–14% (w/v) PEG MME 5000, 0.1 M Na-MES pH 6.0–6.5 and 0.2 M ammonium sulfate in the space group I222 with cell dimensions a=59.0, b=105.8, c=122.1 and a single subunit in the asymmetric unit. All crystals were grown using hanging drop vapor diffusion methods at 23°C. Crystals grew to full-size within 7 days and were stable for several months. The introduction of UDP-glucose and manganese into the 162S and 159S structures was accomplished by overnight microdialysis of crystals against crystallization solution to which 1 mM UDP-glucose and 1 mM MnCl2 was added. All crystals were cryo-protected by the inclusion of 25% (v/v) ethylene glycol in the mother liquor solution and were flash-frozen and evaluated for diffraction properties on a Rigaku H2R rotating anode generator, equipped with an RAXIS IV++ image plate detector and a X-treme cryogenic nitrogen system. X-ray diffraction data were collected on our RAXIS IV++ for the apo and UDP-glucose forms of the 162S enzyme. The diffraction data for the apo-forms of the 159N and 159S enzymes, as well as the UDP-glucose form of the 159S enzyme and the Δ270 enzyme were collected at IMCA-CAT using beamline 17-ID located at the Advanced Photon Source in Argonne National Laboratory. The final data set for the UDP-glucose bound form of the 159S enzyme also included data collected on our home detector in order to compensate for over-saturated low-resolution data from the 17-ID data. Data collected on our home detector were processed and scaled using the HKL (v1.97.2) suite of programs (29), the data collected at 17-ID were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 suite of programs (30). All structures were solved by molecular replacement using the program AMORE (31), as implemented in the CCP4 program package (32), and the original apo-form of rabbit muscle glycogenin as the search model (PDB code 1LL3). Refinement of the solutions to the limit of each diffraction data set was accomplished using the program CNS (v1.1) (33). Visual inspection and manual correction of the resulting model structures was accomplished using the program package O (34).

RESULTS

Purification and Characterization of Δ270 and Enzymes with Mutations at Positions 159 and 162

Truncation of the full-length glycogenin molecule at residue 270 resulted in a fully active enzyme (Δ270) whose specific activity for self- or trans-glucosylation was indistinguishable from the full-length enzyme (Table 1). Mutation of Asp159 or Asp162 to either Ser or Asn resulted in stable enzymes that could readily be purified for enzymatic study. These mutants migrated on SDS-PAGE faster than the respective active parent enzymes, suggesting reduced self-glucosylation in E. coli (not shown). Consistent with this observation, the mobility of the full-length mutant enzymes on SDS-PAGE was identical to wild-type enzyme expressed and purified from an E. coli strain defective in UDP-glucose production (6). The wild-type glucosylated glycogenin, wild-type non-glucosylated glycogenin, full-length 159S, full-length 162S, Δ270-159S, and Δ270-162S were all determined by gel-filtration to exist as >95% dimer (103,000 daltons for the full-length enzymes or 58,000 daltons for the Δ270 enzymes) in solution with less than 5% of a tetrameric species (176,000 daltons for full-length enzyme or 102,000 daltons for the Δ270 enzymes) present. However, the full-length 159N, 162N and the Δ270-162N enzymes appeared to exist as both tetrameric and dimeric species in solution, with approximately twice the concentration of tetramer versus dimer under the conditions of our gel-filtration analysis. No monomeric or higher order species were detected for any of the enzymes analyzed by this method.

Table 1.

Activity Levels for Wild-type and Mutated Glycogenin Enzymes

| Enzyme | Self-Glucosylation (min−1) | Trans-Glucosylation (min−1) | UDP-Glucose Hydrolysis (min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type (glucosylated) | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.01 ± 0.30 |

| Wild-type non-glucosylated | 0.84 ± 0.30 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 0.39 ± 0.03 |

| 162S | <0.005 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| 162N | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 159S | <0.005 | <0.001 | 0.074 ± 0.002 |

| 159N | 0.006 ± 0.007 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.082 ± 0.030 |

| Δ270 | 0.34 ± 0.08 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 0.95 ± 0.10 |

| Δ270-162S | <0.005 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Δ270-162N | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Δ270-159S | <0.005 | <0.001 | 0.23 ± 0.15 |

Enzymatic Activity Measurements

The 159S, 159N, 162N and 162S mutant glycogenin enzymes possess self-glucosylation activities below the limit of detection of the assay. Increasing the concentration of UDP-glucose in the assay from 30 μM to 515 μM or increasing the incubation time did not change the results (Table 1). The 162N mutant possessed undetectable activity for the trans-glucosylation of maltose and the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose to free glucose under the conditions of the assay. The 162S mutant was between 18- and 30-fold less active for the trans-glucosylation of maltose and between 190- and 340-fold less active for the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose, depending on whether the activity measurements were performed on the full-length 162S enzyme or on the Δ270-162S enzyme. The trans-glucosylation activity of the 159S enzyme was reduced to undetectable levels, while its activity for the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose was reduced only 4–14-fold, depending on whether the mutation was in the full-length enzyme or the Δ270 enzyme. The ability of the 159N enzyme to catalyze the trans-glucosylation of maltose was reduced by 260-fold, but similar to the 159S enzyme, the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose was only reduced 12-fold.

For the wild-type glucosylated form of glycogenin, an analysis of the reaction products obtained from the trans-glucosylation assay shows that 93% of the transferred glucose molecules appear in maltotriose, 6% are attached to glycogenin and 1% is liberated as free glucose. In the hydrolytic reaction 63% of the transferred glucose molecules are found as free glucose and 37% are attached to glycogenin. The non-glucosylated form of the wild-type enzyme had less hydrolytic activity relative to its self-glucosylation activity. The products of the hydrolytic assay showed that 31.5% of the transferred glucose appears as free glucose and 68.5% are attached to glycogenin. In contrast, the trans-glucosylation of maltose by the non-glucosylated enzyme showed results nearly identical to that of the glucosylated form of glycogenin, with 5.5% of the transferred glucose molecules attached to glycogenin, 94.5% appearing in maltotriose and no detectable free glucose. There was also no evidence for the formation of maltotetrose during the time course of the trans-glucosylation assays.

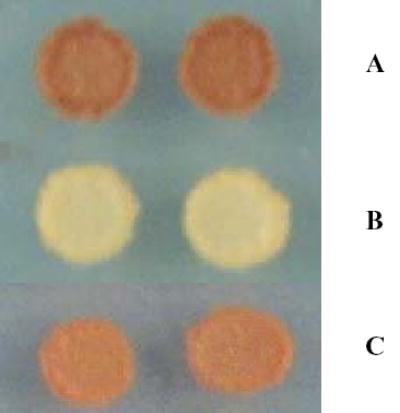

Rescue of Glycogen Accumulation in Yeast

We examined the ability of the Δ270 construct of glycogenin to support glycogen accumulation in an indirect manner. Since the Δ270 enzyme was capable of both self- and trans-glucosylation reactions, we could not be sure that any glycogen accumulation was not due to the ability of the Δ270 enzyme to trans-glucosylate an alternative acceptor molecule in yeast. We have previously shown that the F194 mutant of glycogenin was incapable of self-glucosylation, but could glucosylate alternative acceptor molecules including catalytically inactive glycogenin molecules (10). The yeast S. cerevesiae contains two distinct genes for glycogenins and double knockout strains cannot accumulate measurable levels of glycogen (9). Transformation of glg1glg2 strains of yeast with native mammalian forms of glycogenin can rescue this glycogen accumulation defect (Figure 1a). In contrast, glg1glg2 strains of yeast transformed only with the F194 mutant form of glycogenin do not accumulate significant amounts of glycogen (Figure 1b). For this experiment, we created a truncated form of the human glycogenin-1 gene in which the manganese ligand D103 was mutated to alanine (Δ271-103A). We knew from prior assays that this protein was devoid of both self- and transglucosylation activities (J. Zhou, unpublished). Expression of this mutant alone could not rescue the glycogen accumulation defect in glg1glg2 yeast (not shown). However, when both the F194 and Δ271-103A mutant glycogenins were transformed into glg1glg2 yeast cells, glycogen accumulation was restored, albeit at slightly lower levels than are obtained with wild-type glycogenin (Figure 1c). This result demonstrates that the Δ271-103A acts as a glucose acceptor for the F194 mutant and is able to support glycogen synthesis in the yeast cell.

Figure 1.

JZ4-a cells stained for glycogen accumulation using iodine vapor. A) JZ4-a cells transformed only with wild-type glycogenin-1. B) JZ4-a cells transformed only with 194F glycogenin-1. C) JZ4-a cells transformed with both 194F-glycogenin-1 and Δ271-103A glycogenin-1.

Structures

The three-dimensional structures for the Δ270 enzyme complexed with UDP and Mn2+ and the full-length apo-form of the 159N enzyme, the apo- and UDP-glucose/Mn2+ bound forms of 159S and the apo- and UDP-glucose/Mn2+ bound forms of 162S have been solved to resolutions between 2.6 and 1.98 Å. All structures, except the Δ270 crystals, have a monomer within the asymmetric unit with the biological dimer created by one of the crystallographic dyad axes in the unit cell. For those structures solved in the I222 space group, the additional dyad axes form what is likely to be a non-physiologic back-to-back tetramer mediated by crystallographic contacts with a sulfate ion precisely located at the intersection of the three dyad axes in this space group (‘a special position’). This interaction was also observed in the wild-type enzyme crystallized in this same space group (20). In the Δ270 structure, the biological dimer comprises the asymmetric unit and the additional dyad axis in the P64 space group forms a front-to-front type of tetramer that may have implications for one mode of self-glucosylation (Figure 2a). Interestingly, the orientation of the monomers along their respective dimer axes in these two space groups differs by 6.5°, suggesting that the dimer interaction surface in glycogenin is a flexible one (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Subunit relationships among glycogenin crystal forms. A) Tetrameric association formed by crystallographic contacts between the dimers that comprise the asymmetric unit in the Δ270 crystals. Each subunit is colored differently and the position of Tyr194 in each subunit is highlighted using purple space-filling atoms and the position of the bound UDP molecules is highlighted using blue space-filling atoms. B) Alignment of the dimer formed by one of the crystallographic axes in the I222 space group (red) with the dimer of the Δ270 enzyme that comprises the asymmetric unit of the P64 space group (yellow). For this figure only the respective “A” subunits were aligned. The red arrow indicates the amount of additional rotation required to align the “B” subunits using the molecules oriented in this manner. Figure prepared using the programs MOLSCRIPT (38) and Raster3D (39,40).

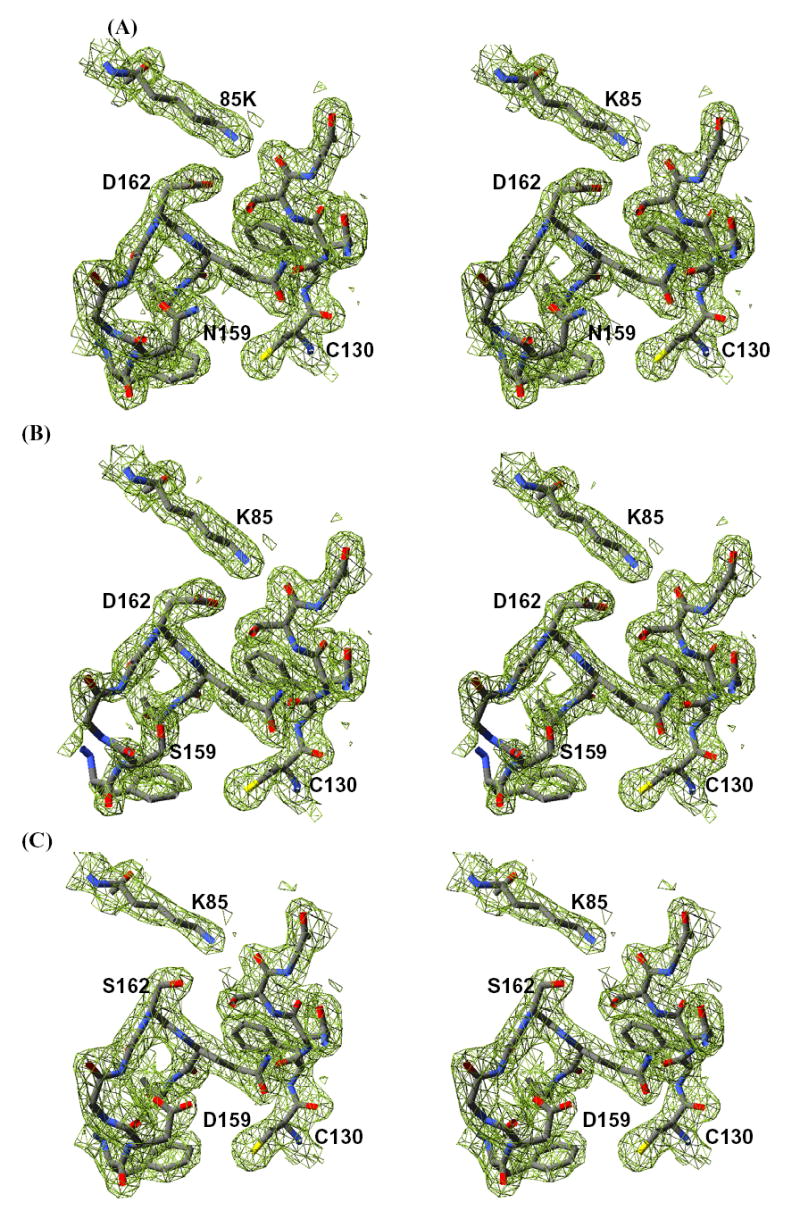

At the subunit level, the structures of all the mutant enzymes are nearly identical to the wild-type enzyme structure (r.m.s.d. values for Cα atoms between 0.3 and 0.4 Å). The overall structures of the respective mutant enzymes are identical to each other (r.m.s.d. values for Cα atoms <0.2 Å for each comparison set). The mode of interaction between the enzyme and the bound substrate molecules is also unchanged from that described in previous work (20). All structures maintain the same non-proline cis-peptide bond between residues 118 and 119 (20). The side chains for the substituted residues at positions 159 and 162 are clearly visible in the electron density maps (Figure 3). Compared with wild-type enzyme, all structures exhibit electron density for additional residues in the disordered loop between positions 233 and 240. In the 159S/N and 162S mutant structures, this would appear to be mediated by contact with the side chain of an ordered Tyr194 residue. In the Δ270 structure, the increased order is probably due to the formation of the face-to-face tetramer (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Stereo-diagrams showing the electron density for the apo-enzyme forms of the three mutant enzymes. A) 2Fo-Fc electron density generated from a simulated-annealing composite omit map contoured at one standard deviation for the residues surrounding positions 159 and 162 in the 159N enzyme. B) 2Fo-Fc electron density generated from a simulated-annealing composite omit map contoured at one standard deviation for the residues surrounding positions 159 and 162 in the 159S enzyme. C) 2Fo-Fc electron density generated from a simulated-annealing composite omit map contoured at one standard deviation for the residues surrounding positions 159 and 162 in the 162S enzyme. Figure prepared using SPDB Viewer (41) and rendered using POV-Ray (42).

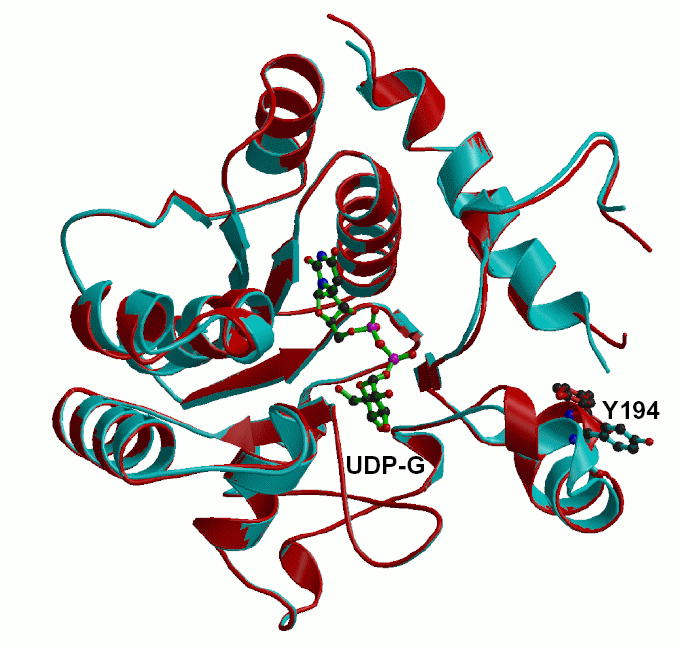

As with the full-length wild-type enzyme, which crystallized in the same space group and with similar cell dimensions (20), none of the full-length mutant structures exhibited any electron density for residues 265–333. One point of difference in these structures is that the electron density for residues 190–195 is stronger in the mutant enzymes such that the side chain of Tyr194 can now be visualized. Prior wild-type structures, as well as the Δ270 structure reported here, exhibit no electron density for the side chain of Tyr194 and the density for the main chain atoms in this region is not always continuous. The helix in which the residue lies is also shifted from the position seen in the wild-type structure (Figure 4). This shift in the position of the helix is likely due to the new packing interactions contributed by the now more ordered side chain of Tyr194.

Figure 4.

An alignment of the 162S enzyme (red) with the previously determined wild-type enzyme (cyan) showing the new positions for residue 194 and the helix in which it resides. The position of UDP-glucose is also shown for context to the active site. Figure prepared using the programs MOLSCRIPT (38) and Raster3D (39,40).

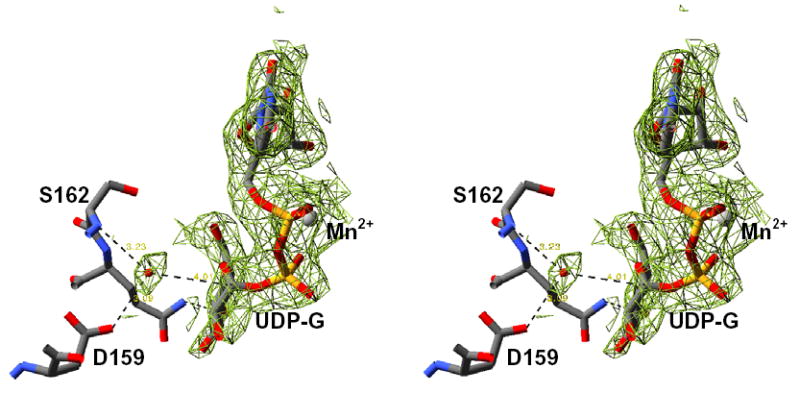

The 162S enzyme shows the least change in active site structure when compared to the wild-type enzyme, while both the 159S and 159N structures exhibit local changes in structure associated with the differences in the hydrogen-bonding capabilities of these residues (Figure 3). Both the 159S and 159N structures exhibit discrete disordering of Tyr196, which normally forms a hydrogen bond with Asp159 across the dimer interface (20). In addition, the 159S enzyme exhibits an increase in the conformational flexibility for residues 157 to 160, as evidenced by higher B-factors and weaker main chain electron density (Figure 3). This is not entirely corrected upon UDP-glucose binding. In both the 159S and 162S UDP-glucose/Mn2+ bound structures an ordered water molecule is located 4 Å from the C1 atom of the glucose moiety. It is held in position through interactions with the main chain amide nitrogen of residue 162 and either the side chain carboxyl oxygen of Asp162 or Asp159, depending on the position of the mutation (Figure 5). A water molecule is bound in a similar location in the wild-type UDP-glucose structure and forms hydrogen bonds with both the main chain nitrogen of Asp162 and its side chain carboxylate (20).

Figure 5.

Stereodiagram showing the 2Fo-Fc electron density generated from a simulated-annealing composite omit map contoured at one standard deviation for the bound Mn2+/UDP-glucose and water molecule in the 162S enzyme. Figure prepared using SPDB Viewer (41) and rendered using POV-Ray (42).

DISCUSSION

Prior investigation of glycogenin has established its critical role in the initiation of glycogen synthesis (2,3). In this study, we sought to assess the effects of mutations at residues within the active site that were designed to establish the chemical requirements for glucosyltransfer. We also examined the structural and functional effects of truncating the glycogenin enzyme at the end of the catalytic domain (residue 271) which eliminates the putative glycogen synthase-binding domain (4,9).

We solved the three-dimensional structures of four of the mutant constructs, both in the presence and absence of bound nucleotide. All structures are highly similar to the wild-type enzyme, except that the mutations at positions 159 and 162, which resulted in non-glucosylated enzymes, affected the positioning of the α-helix that contains the site of self-glucosylation, Tyr194. Since the space-group and, thus, the crystal-packing contacts are the same for these mutants and for the wild-type enzyme, it is likely that this shift in helical position reflects the actual position of the helix prior to self-glucosylation and that the position observed in the wild-type enzyme reflects the position of the helix following self-glucosylation. This is further supported by the structure of the Δ270 enzyme, which like the wild-type enzyme is glucosylated and exhibits the same helical position and disordering of Tyr194 despite distinctly different crystal packing contacts.

Although the mutations have minimal impact on the three-dimensional structures of the enzymes, two of the mutations, 159N and 162N, had an impact on the oligomerization of the enzyme in solution. All enzymes existed as a mixture of tetramer and dimer in solution under the conditions of our gel-filtration experiments. For the 159S and 162S forms, more than 95% of the enzyme is present as a dimeric species in solution. However, for both the 162N and 159N enzymes, greater than 66% of the enzyme was present as a tetrameric species in solution, with the remaining fraction existing as a dimeric species. The fact that all enzyme samples, including the wild-type enzyme, contain both species suggests that the mutations are not creating novel interactions, but rather altering the equilibrium between pre-existing states. We do not believe that this altered equilibrium significantly impacts the enzymatic properties reported here, since both the 159S and 159N enzymes had similar enzymatic characteristics, similar three-dimensional structures, but quite different dimer-tetramer distributions. Prior work has shown that when glycogenin concentration in the assay is varied, half-maximal activity is achieved when the concentration is in the low micromolar range (10). Initially, it was thought that catalysis occurred within a dimer and that this concentration dependence might represent the dissociation of the dimers into inactive monomers (10). Alternatively, based on the gel-filtration data presented here, the concentration dependence might reflect an association between dimers in solution to form a Michaelis complex, such as the tetramer observed in the Δ270 structure. Further exploration of this phenomenon is clearly warranted.

Previous work has shown that glycogenin, purified as recombinant protein from bacteria or from tissue sources, is susceptible to proteolysis and yields a predominant species approximately six kilodaltons smaller than the intact enzyme (35). This proteolytic fragment was shown to be active for self-glucosylation and was suggested to represent the N-terminal catalytic fragment of the enzyme (35). Our own structural investigations are consistent with this finding, since none of our full-length structures exhibit interpretable electron density past residue 265, despite the presence of these residues in the crystals (20). We found that glycogenin truncated at residue 270 produced a stable and active enzyme with properties similar to the wild-type enzyme for all enzyme reactions investigated. The Km for UDP-glucose was not adversely affected. Thus, at least for the glucosyltransferase reaction, the C-terminal domain does not significantly contribute to the activity of the enzyme.

An important question remains: what effect do the C-terminal 62 residues have on glycogenin function? We report here that the structural scaffold of a similarly truncated, but functionally inactive form of human glycogenin-1 (Δ271-103A) was able to rescue glycogen accumulation in a glg1glg2 yeast strain when co-transfected with the F194 form of glycogenin-1. The F194 form of glycogenin is incapable of self-glucosylation and cannot by itself rescue the glycogen accumulation defect in glg1glg2 yeast strains. The F194 enzyme has been shown to catalyze the addition of glucosyl chains to other molecules of glycogenin (10) and so the addition of glucosyl chains to the Δ271-103A form of glycogenin by the F194 enzyme is the most reasonable explanation for the rescue of the glycogenin accumulation defect. Consequently, yeast glycogen synthase is apparently capable of recognizing the truncated, but glucosylated form of glycogenin as its substrate for further glycogen synthesis. Qualitative analysis of the level of glycogen accumulation showed that the truncated form of human glycogenin-1 accumulated less glycogen when compared to full-length glycogenin-1 (Figure 1). This suggests that while not essential for self-glucosylation and glycogen accumulation, the C-terminal domain of glycogenin may augment the level of glycogen that can be attained in vivo.

A surprising aspect of this study was the extent to which both the full-length and Δ270 enzymes catalyzed the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose to UDP and glucose. For the glucosylated forms of glycogenin, the kcat for this reaction was approximately 3-times that for self-glucosylation and approximately 50% of the rate for the trans-glucosylation of maltose (Table 1). Previous work has shown that the transglucosylation reaction proceeds with a greater kcat value than self-glucosylation and this work is consistent with prior results (12, 36). However, it is interesting that the trans-glucosylation reaction appears to suppress both the hydrolytic reaction and the intrinsic self-glucosylation reaction. Since the assays use the same preparation of glycogenin, it suggests that the addition of the exogenous acceptor molecule to the assay components increases the efficiency of the transferase reaction. We feel that this result is a consequence of utilizing glycogenin that has already added an average of four to five glucose residues to itself during expression in E. coli. Prior work has shown that the efficiency of glucosyltransfer decreases with increasing glucose chain-length attached to Tyr194 (7). The decreased efficiency might be due to an inability to stably bind the longer chains of glucose in the acceptor site. Consequently, it is possible that the hydrolytic reaction gains in apparent efficiency due to decreased occupancy of the acceptor site. Addition of maltose to such preparations of glycogenin apparently restores the native efficiency of the transferase reaction by effectively increasing the occupancy of the acceptor site. This hypothesis is supported by the data from the non-glucosylated enzyme purified from E. coli deficient in UDP-glucose. The non-glucosylated form of the enzyme had less hydrolytic activity relative to its self-glucosylation activity, while the transglucosylation activity of the non-glucosylated form of glycogenin was identical to the glucosylated forms.

The precise mechanism by which retaining glycosyltransferases catalyze their reaction has been a subject of controversy. One view is that, like retaining glycosidases, retaining glycosyltransferases catalyze the enzymatic transfer via a double nucleophilic substitution reaction (double SN2 reaction) in which a covalent intermediate between an active site nucleophile and the donor sugar is formed with inverted stereochemistry, followed by transfer of the donor sugar to the acceptor substrate with subsequent re-inversion of the stereochemistry at the anomeric carbon (23). Although, recent data from mutagenic and structural studies on α-1,3-galactosyltransferase and also LgtC appear to support a SNi mechanism that lacks a covalent enzyme-glycosyl intermediate (37). We have previously suggested that, based on sequence conservation among glycogenin enzymes and among retaining glycosyltransferases, Asp162 could function as the catalytic nucleophile for a double-displacement mechanism (20). However, we could not rule out Asp159 as the putative nucleophile since it is also a conserved residue among glycogenins, although not in all glycosyltransferases. Both Asp159 and Asp162 are approximately equidistant from the C1” atom of the bound UDP-glucose molecule in our structures.

To test the respective roles of these two potential catalytic residues, each residue was substituted with either Asn or Ser. The rationale for these choices was that Asn is isosteric but chemically inert for nucleophilic attack or general acid/base catalysis and that Ser lacks general acid/base capability but could function as a weak nucleophile. All four mutations yielded enzymes that lacked detectable self-glucosylation activity and thus provide little mechanistic insight. However, measurement of each mutant enzyme’s ability to transfer glucose to maltose as the acceptor or the enzyme’s ability to catalyze the futile hydrolytic formation of free glucose from UDP-glucose proved more informative. Both mutations at position 162 decreased UDP-glucose hydrolytic activity by at least 190-fold (Table 1). The 162N mutant enzyme showed a greater than 1000-fold decrease in both the UDP-glucose hydrolysis and glucosyltransferase activities, such that any activity is below the ability of our assays to detect. The 162S mutant exhibited UDP-hydrolysis activity that was 190 to 300-fold lower than the wild-type enzyme and glucosyltransferase activity that was 20 to 30-fold lower than wild-type enzyme, depending on the background of the mutations (Δ270 or full-length, respectively). The differences in the behavior of the 162S and 162N mutant can be related to the chemical character of their substituted side chains. The side chain of Asn is chemically inert as a nucleophile under the conditions of the assay; consequently the 162N mutant had the lowest activity in all assays since, in a double nucleophilic displacement mechanism, both reactions require the participation of a nucleophile. Interestingly, the 162S mutant did possess measurable hydrolytic and glucosyl-transferase activity, suggesting that the Ser side chain can be activated to serve as a weak nucleophile in the glycogenin active site. The juxtaposition of Lys85 to the Ser162 side chain (Figures 3) could influence the environment of this residue to lower the pKa of the hydroxyl group and consequently produce a reasonably good nucleophile. The fact that the hydrolytic and transferase reactions are differentially affected could be related to the fact that acceptor binding may further desolvate the active site and thereby increase the nucleophilicity of the Ser residue for the transferase reaction. Previous work has shown the mutation of Lys85 to Gln inactivated glycogenin for glucosyltransferase activity, suggesting that the pairing of the protonated amino group (Lys85) and the deprotonated putative nucleophile at position 162 is essential for catalysis.

The mutations at position 159 reduced glucosyltransferase activity for maltose by at least 260-fold, but only reduced hydrolytic activity between 4 and 14-fold, depending on the background of the mutation. These data, combined with the data for 162S and 162N, suggest that the 159N/S mutants were deficient not in the initial breakage of the phosphoryl-carbon bond but in activating the acceptor molecule (either maltose or water). The position of Asp159, in the context of other glycosyltransferases, is consistent with participation in acceptor binding and activation (13–19, 37). Consequently, we suggest that Asp159 is involved in both binding and activation of the acceptor molecule. In principle, the side chains of both Ser and Asn could form a hydrogen bond with the acceptor molecule to correctly position it for catalysis, but then cannot facilitate the deprotonation of the 4’OH due to their ineffectiveness in general acid/base chemistry. The fact that the 159S enzyme was devoid of transferase activity and the 159N enzyme possessed low, but measurable, transferase activity suggests that hydrogen-bonding capability alone is insufficient for full functionality. This conclusion is based on the interactions contributed by residue 159 to the local structure of the active site. The side chain of residue 159 caps the peptide nitrogen atom of the adjacent glycine residue in all structures we have determined (Figure 3). However, the side chains of both Asp and Asn can form hydrogen bonds to an acceptor molecule with the opposing carboxyl oxygen or the opposing amide nitrogen, respectively (Figure 3). The unbranched and smaller side chain of Ser cannot perform both functions, and so the 159S mutant enzyme must either sacrifice interactions with the acceptor molecule or the structural integrity of this important area of the enzyme. In either case, activity for the glucosyltransferase reaction is more severely affected in the 159S enzyme. That glucosyltransferase activity in the 159N enzyme was reduced 260-fold suggests that hydrogen-bonding capability is secondary to the ability of the residue to accept a proton and thereby activate the acceptor molecule.

Our data cannot address the issue of whether the reaction goes through a SN2 or SNi mechanism. However, the roles of these two residues do not change significantly if, in fact, the SNi mechanism is the correct interpretation. In a SNi mechanism, Asp162 would facilitate breakage of the carbon-phosphoryl bond by electrostatic stabilization of the oxocarbenium intermediate, while Asp159 would position and activate the incoming acceptor molecule.

In conclusion, we have shown that neither truncation of mammalian glycogenin nor the selected substitution of key catalytic residues within the substrate binding and active sites results in large changes in the tertiary structure of the catalytic core of the protein. The most significant changes in structure were associated with lack of glucosylation of Tyr194 that result from the substitutions of Asp159 and Asp162, while only limited and local changes to the structure were observed at the actual site of the mutations. The mutations at positions 159 and 162 also appear to have little effect on the structure of the ground-state enzyme·UDP-glucose complex, suggesting that the catalytic effects of these substitutions are manifested either in the formation of the ternary complex with the acceptor molecule or during the actual glucosyltransfer reaction. Substitutions at both 159 and 162 are associated with a lack of self-glucosylation activity as well as severe reductions in the transglucosylation of maltose or the hydrolysis of UDP-glucose. The differential effects of the mutation on these distinct reactions support a direct role for Asp162 in the chemical step required for retaining glycosyltransferases and a role for Asp159 in the binding and activation of the acceptor molecules. The results of the structure determination on the Δ270 enzyme, the mutational effects on the dimer/tetramer equilibrium of glycogenin and the fact that a catalytically inactive form of the truncated human glycogenin-1 enzyme could support glycogenin accumulation when acted upon by a F194 variant of glycogenin in yeast suggest that the formation of higher order associations between glycogenin dimers in vitro and in vivo may be a key aspect of its function during the priming of the glycogen synthetic process.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Lisa Keefe and staff at IMCA-CAT, beamline 17-ID, at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory for beamline access and support. We wish to thank the Protein Expression Core of Indiana University School of Medicine, for providing purified forms of glycogenin used for the completion of this work. The Protein Expression Core is supported by the Indiana Genomics Initiative (INGEN®), which is supported in part by Lilly Endowment Inc. The coordinates and structure factors for all structures reported here have been deposited in the Protein Data Back under the codes 1ZCT, 1ZCU, 1ZCV, 1ZCY, 1ZDF, 1ZDG (Table 2).

Table 2.

Crystallographic Data for Mutated Glycogenin Enzymes

| Apo-159S | UDPG-159S | Apo-159N | Apo-162S | UDPG-162S | UDP-Δ270 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Space Group | I222 | I222 | I222 | I222 | I222 | P64 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0–1.98 | 50.0–2.3 | 50.0–1.98 | 25.0–2.0 | 33.0–2.45 | 50.0–2.6 |

| Total Observations | 183,136 | 136,268 | 183,866 | 87,013 | 84,070 | 210,226 |

| Unique Reflections | 26,210 | 16,814 | 26,783 | 24,514 | 14,237 | 20,872 |

| Complete (%) | 96.2 (92.8) | 95.8 (81.5) | 99.3 (98.6) | 94.9 (69.2) | 99.4 (93.8) | 91.2 (53.8) |

| <I>/σ<I> | 40.3 (9.4) | 18.3 (6.6) | 49.5 (9.7) | 22.3 (3.0) | 21.7 (5.6) | 28.2 (7.4) |

| Rmerge | 0.041(0.19) | 0.094(0.20) | 0.034(0.18) | 0.043(0.31) | 0.063(0.22) | 0.063(0.21) |

| Refinement | ||||||

| Rfree/Rwork | 0.238/0.226 | 0.244/0.237 | 0.218/0.209 | 0.229/0.216 | 0.217/0.199 | 0.253/0.239 |

| R.m.s.d. from ideal bonds (Å) | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.009 |

| R.m.s.d. from ideal angles (°) | 1.20 | 1.43 | 1.17 | 1.30 | 1.20 | 1.39 |

| PDB code | 1ZCY | 1ZDG | 1ZCV | 1ZCU | 1ZDF | 1ZCT |

References

- 1.Roach, P. J., Skurat, A.V. & Harris, R.A. (2001) in Handbook of Physiology (ed. Cherrington, L. S. J. a. A. D.), pp 609–647.

- 2.Pitcher J, Smythe C, Cohen P. Eur J Biochem. 1988;176:391–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ. FASEB J. 1988;2:3097–3103. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.15.2973423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roach PJ, Skurat AV. Prog Nucl Acid Res & Mol Biol. 1997;57:289–316. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smythe C, Caudwell FB, Ferguson M, Cohen P. EMBO J. 1988;7:2681–6. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03121.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso MD, Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ, Preiss J. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:222–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smythe C, Cohen P. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200:625–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1991.tb16225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alonso MD, Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ. FASEB J. 1995;9:1126–1137. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.12.7672505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng C, Mu J, Farkas I, Huang D, Goebl MG, Roach PJ. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6632–40. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.6632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin A, Mu J, Yang J, Roach PJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;363:163–70. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao Y, Mahrenholz AM, DePaoli-Roach AA, Roach PJ. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:14687–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alonso MD, Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:38–42. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80580-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gastinel LN, Bignon C, Misra AK, Hindsgaul O, Shaper JH, Joziasse DH. EMBO J. 2001;20:638–49. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.4.638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gastinel LN, Cambillau C, Bourne Y. EMBO J. 1999;18:3546–57. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unligil UM, Zhou S, Yuwaraj S, Sarkar M, Schachter H, Rini JM. EMBO J. 2000;19:5269–80. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha S, Walker D, Shi Y, Walker S. Prot Sci. 2000;9:1045–52. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.6.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Persson K, Ly HD, Diekelmann M, Wakarchuk WW, Withers SG, Strynadka NCJ. Nature Struct Biol. 2001;8:166–75. doi: 10.1038/84168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charnock SJ, Davies GJ. Biochem. 1999;38:6380–5. doi: 10.1021/bi990270y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patenaude SI, Seto NOL, Borisova SN, Szpacenko A, Marcus SL, Palcic MM, Evans SV. Nature Struct Biol. 2002;9:685–690. doi: 10.1038/nsb832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gibbons BJ, Roach PJ, Hurley TD. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:463–477. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00305-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unligil UM, Rini JM. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:510–7. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00124-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapitonov D, Yu RK. Glycobiol. 1999;9:961–78. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.10.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinnott ML. Chem Rev. 1990;90:1171–1202. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vocadlo DJ, Davies GJ, Laine R, Withers SG. Nature. 2001;412:835–8. doi: 10.1038/35090602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sikorski RS, Heiter P. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rothstein R. Meth Enzymol. 1983;110:202–210. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiestl RH, Geitz RD. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hardy TA, Roach PJ. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23799–23805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Meth Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minor W, Tomchick D, Otwinowski Z. Structure. 2000;8:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Navaza J. Acta Cryst. 1994;A50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 32.COLLABORATIVE COMPUTATIONAL PROJECT, NUMBER 4. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstlev RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges N, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Cryst. 1998;D54:905, 21. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Acta Cryst. 1991;A47:110–9. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao Y, Steinrauf LK, Roach PJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;319:293–198. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alonso MD, Lomako J, Lomako WM, Whelan WJ. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15315–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Y, Swaminathan J, Deshpande A, Biox E, Natesh R, Xie Z, Acharya KR, Brew K. Biochem. 2003;42:13512–13521. doi: 10.1021/bi035430r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraulis PJ. J Appl Cryst. 1991;26:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merrit EA, Murphy MEP. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:869–873. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bacon DJ, Anderson WF. J Molec Graphics. 1988;6:219–220. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guex N, Peitsch MC. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. ( http://www.expasy.org/spdbv/) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cason, C.J. (1999) POV-Ray for Windows, version 3.1, http://www.povray.org/