Abstract

Using a genetic screen, we have identified a previously uncharacterized Saccharomyces cerevisiae open reading frame (renamed PML39) that displays a specific interaction with nucleoporins of the Nup84 complex. Localization of a Pml39-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion and two-hybrid studies revealed that Pml39 is mainly docked to a subset of nuclear pore complexes opposite to the nucleolus through interactions with Mlp1 and Mlp2. The absence of Pml39 leads to a specific leakage of unspliced mRNAs that is not enhanced upon MLP1 deletion. In addition, overexpression of PML39-GFP induces a specific trapping of mRNAs transcribed from an intron-containing reporter and of the heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein Nab2 within discrete nuclear domains. In a nup60Δ mutant, Pml39 is mislocalized together with Mlp1 and Mlp2 in intranuclear foci that also recruit Nab2. Moreover, pml39Δ partially rescues the thermosensitive phenotypes of messenger ribonucleoparticles (mRNPs) assembly mutants, indicating that PML39 deletion also bypasses the requirement for normally assembled mRNPs. Together, these data indicate that Pml39 is an upstream effector of the Mlps, involved in the retention of improper mRNPs in the nucleus before their export.

INTRODUCTION

Compartmentalization of eukaryotic cells allows the physical separation of the genetic material from its sites of expression into proteins. Part of the nucleocytoplasmic flux of genetic information is mediated by messenger RNAs (mRNAs), which are exported from the nucleus through nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). mRNA export to the cytoplasm exhibits unique features that distinguishes it from other transport pathways. First, export of most mRNAs is not directly dependent on the nucleocytoplasmic gradient of the small GTPase Ran. Second, the mRNA is not exported as such but packaged within a battery of proteins—the so-called heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein (hnRNPs)— giving rise to the messenger ribonucleoparticle (mRNP). Finally, mRNA export is tightly coupled with transcription and with the different posttranscriptional processing events, e.g., 5′-capping, splicing, 3′-cleavage, and polyadenylation (reviewed in Jensen et al., 2003; Rodriguez et al., 2004). For example, the yeast shuttling mRNA-binding protein Nab2, is required both for poly-A tail length control and proper mRNA export (Hector et al., 2002). In addition, cotranscriptional loading of a set of proteins onto the pre-mRNA facilitates the subsequent binding of mRNA export factors. In yeast, the THO complex (Hpr1–Tho2-Mft1–Thp2), associated with actively transcribed genes, recruits the mRNA export adaptors Yra1 and Sub2 within a large conserved multiprotein complex called TREX (for transcription and mRNA export; Strasser et al., 2002). As an alternative pathway, the Sus1 protein, a component of the SAGA histone acetylase complex, is able to bind the Sac3–Thp1 complex required for efficient mRNA export (Rodriguez-Navarro et al., 2004).

mRNP assembly systematically concludes in the recruitment of the conserved mRNA export receptor Mex67/Mtr2 (TAP/p15 in vertebrates; Segref et al., 1997). Binding of Mex67 to the mRNP is thought to depend on direct interactions with alternate adaptors, mainly Yra1 (Strasser and Hurt, 2000), but also Sac3 (Fischer et al., 2002) or the SR-like hnRNP Npl3 (Gilbert and Guthrie, 2004). In turn, Mex67-Mtr2 is able to dock export competent mRNPs to the NPC through interaction with a subset of nucleoporins characterized by their repeated phenylalanine-glycine (FG) motifs (reviewed in Rodriguez et al., 2004). In addition, mRNA export requires some nucleoporins devoid of FG motifs, possibly involved in the integrity of NPC architecture. One such structural building block is the conserved Nup84 NPC subcomplex, made of seven subunits in budding yeast (Nup120, Nup85, Nup145-C, Nup84, Nup133, Seh1, and a fraction of Sec13) (Lutzmann et al., 2005, and references therein); indeed, yeast strains deleted for most of the subunits of the complex display mRNA export defects. The last step of mRNA export is the delivery of the mRNP particle to the cytoplasm, and it requires Dbp5, a conserved helicase associated with the cytoplasmic face of NPCs that could provoke the remodeling of the exported mRNP and consequently ensure the directionality of the process (reviewed in Rodriguez et al., 2004).

To prevent the nuclear export and translation of mRNAs carrying defects in their nucleotide sequence and/or in their packaging into mRNPs, eukaryotic cells have evolved quality control mechanisms that prevent the synthesis of dysfunctional proteins (reviewed in Jensen et al., 2003 and Vinciguerra and Stutz, 2004). For example, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) allows the elimination of mRNA-harboring defects such as premature stop codons. In the nucleus, the completion of mRNA surveillance is partially performed by Rrp6, an exonuclease specific for nuclear exosome and involved in the degradation of unprocessed mRNAs as well as aberrant mRNPs (Hilleren et al., 2001). Another aspect of mRNA surveillance is the active retention of intron-containing mRNAs in the nucleus. In budding yeast, cis- and trans-acting mutations affecting the splicing process were first shown to enhance pre-mRNA export in the cytoplasm (Legrain and Rosbash, 1989). In addition, genes involved specifically in pre-mRNA retention but not in splicing, were identified. One of them, MSL5, encodes a protein recognizing intronic sequences at the level of the branchpoint (BP) (Rutz and Seraphin, 2000). More recently, a biochemical purification of splicing complexes led to the identification of the trimeric retention and splicing (RES) complex. Interestingly, deletion of one of its subunits, encoded by the PML1 gene, gave rise to an mRNA leakage phenotype without affecting the splicing process (Dziembowski et al., 2004). Finally, at the level of the nuclear envelope barrier, the NPC-associated protein Mlp1 (myosin-like protein 1) is required for nuclear retention of intron-containing mRNAs (Galy et al., 2004). In addition, genetic and physical interactions between Mlp1 and its paralogue Mlp2, and the mRNP components Yra1 and Nab2, have revealed the more general involvement of Mlps in the nuclear retention of improperly assembled mRNPs (Green et al., 2003; Vinciguerra et al., 2005). These data strongly emphasize the importance of quality control steps before the export of mRNAs out of the nucleus.

Here, we report the functional characterization of a nonessential open reading frame (ORF) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, YML107c, identified on the basis of a strong genetic interaction with constituents of the Nup84 complex. We demonstrate that this protein, renamed Pml39 (for pre-mRNA leakage; 39 kDa), is anchored by the Mlp1-2 proteins to a subset of NPCs, facing the chromatin. The pml39 deletion mutant exhibits unspliced mRNA leakage and genetic interactions with mutations affecting the mRNP assembly factors YRA1 and NAB2. Conversely, Pml39 overexpression leads to a specific trapping of the Nab2 hnRNP as well as mRNAs transcribed from intron-containing genes within discrete nuclear foci. Together, our data demonstrate that the Pml39 protein is an upstream effector of the Mlp-controlled pathway required for retention of improper mRNPs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and Growth Conditions

Yeast growth in standard YPD or SC media, transformation, mating, and sporulation were performed as described previously (Loeillet et al., 2005). Plasmid shuffling was carried out on SC plates containing 50 mg/l uracil and 1 g/l 5-fluoroorotate (Toronto Research Chemicals, North York, Ontario, Canada). For gene induction, 2% glucose or galactose was added to cells cultured in glycerol-lactate (0.17% YNB, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 0.05% glucose, 2% lactate, and 2% glycerol) supplemented with the required nutrients. Except when indicated, cells were grown at 30°C.

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

The genotypes and origins of the strains used are listed in Supplemental Table 1. All strains are isogenic to S288c, except the YRA1 and NAB2 shuffle strains, which are W303 derivatives. Most strains were obtained by successive crosses between single-gene deletants obtained from EUROSCARF (Frankfurt, Germany) (Winzeler et al., 1999), green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged BY derivatives from the GFP collection (Huh et al., 2003; purchased from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and red fluorescent protein (RFP) reference strains kindly provided by Won-Ki Huh (Seoul National University, Korea). Complete ORF deletion and GFP or monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) tagging at the locus were achieved through homologous recombination using cassettes amplified from pFA6a derivatives (Longtine et al., 1998; Huh et al., 2003) or the pOM42 vector (Gauss et al., 2005). N-terminal GFP tagging was followed by Cre-Lox-mediated pop-out of the selection marker (Gueldener et al., 2002). Auxotrophy marker conversion was performed using KanMX::URA3 modifier (Loeillet et al., 2005) or other marker swap plasmids according to described procedures (Voth et al., 2003). Genotypes were checked by PCR and sets of isogenic strains were systematically considered for phenotypic analysis.

Plasmids used in this study and details of their construction are listed in Supplemental Table 2. Sequences of the primers used in this study are available upon request.

Synthetic Lethal and Two-Hybrid Screens

nup133Δ and pml39Δ synthetic genetic array screen were performed as reported previously (Loeillet et al., 2005) using MATα haploids from the EUROSCARF deletion collection. Candidates were further characterized by tetrad analysis.

The two-hybrid screen was carried out by a mating strategy using the FRYL genomic library as described previously (Fromont-Racine et al., 1997). Approximately 108 diploids were screened for histidine prototrophy and β-galactosidase activity. Genomic prey inserts from all positive diploids were characterized by direct sequencing. pACTII prey plasmids were rescued in Escherichia coli and transformed back in Y-187 yeast cells. Interactions were finally confirmed by mating followed by selection on histidine-free SC medium containing 5 mM 3-aminotriazole, and X-Gal lift assay.

Cell Imaging

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed essentially as described previously (Long et al., 1995), using an equimolar mixture of o-LacZ1- and o-LacZ2 CY3-conjugated oligonucleotides. An ultimate 30-min wash in 0.5× SSC was included, and coverslips were finally mounted on Moviol (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA).

For live cell imaging, exponentially growing cells were washed twice, resuspended in minimal medium supplemented with the required nutrients, and mounted on a glass slide. Images were acquired as described previously (Bai et al., 2004; Loeillet et al., 2005) using the MetaMorph 6.2.6 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and were further processed using Adobe Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA). Quantification of fluorescence intensity was performed using MetaMorph.

Splicing and Leakage Assays

All experiments were performed on pools of colonies. β-Galactosidase assays were performed as described previously (Legrain and Rosbash, 1989), except that yeast cells extracts were obtained by bead-beating in Z buffer followed by a 10-min clarification at 10,000 × g.

RESULTS

PML39 Encodes a Previously Uncharacterized Protein of the Nuclear Periphery and Displays a Strong Genetic Interaction with Members of the Nup84 NPC Subcomplex

In S. cerevisiae, Nup84 complex mutants display similar phenotypes, e.g., thermosensitivity, NPC aggregation within the nuclear envelope, mRNA export defects, and DNA double-strand break accumulation (Siniossoglou et al., 1996; Loeillet et al., 2005). To gain further insight into these processes, we undertook a systematic synthetic lethal screening of the collection of nonessential gene deletions using the nup133Δ mutation as a bait. Among the candidate genes of unknown function, one corresponded to the YML107c ORF, which encodes a 39-kDa protein localized to the nuclear periphery according to the general annotation of yeast protein localization (Huh et al., 2003; http://yeastgfp.ucsf.edu/). We therefore initiated the characterization of this gene subsequently termed PML39 (used hereafter).

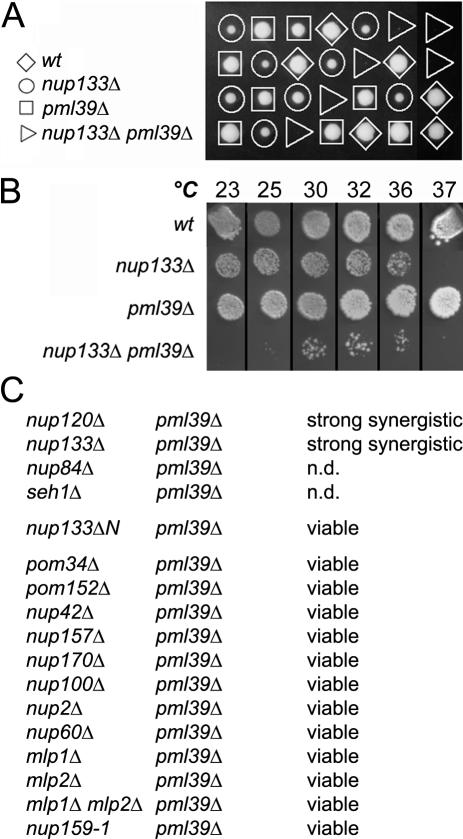

The genetic interaction between NUP133 and PML39 deletion was first confirmed by sporulation of the nup133Δ/+ pml39Δ/+ heterozygote (Figure 1A). Marker segregation revealed that nup133Δ pml39Δ spores form microcolonies at 30°C and showed a strong growth defect at all temperatures assayed (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

The PML39 gene displays a strong genetic interaction with the Nup84 complex. (A) Tetrad analysis of the nup133Δ/+ pml39Δ/+ diploid. Spores were germinated at 30°C and genotypes were inferred from marker segregation analysis. (B) Growth properties of wt, nup133Δ, pml39Δ, and nup133Δ pml39Δ mutants. Equivalent amounts of cells were spotted and grown at the indicated temperatures. (C) Genetic interactions of pml39Δ mutation with other nucleoporins mutants. A pml39Δ strain (YV615) was used as a bait for a secondary synthetic lethal screening of nucleoporin deletants issued from the EUROSCARF MATα collection except nup157Δ (YV726) and nup159-1 (LGY101). Interactions with nup133ΔN (YV529) and mlp1Δ mlp2Δ (YV726) mutants were scored by crosses with pml39Δ (Y16507). n.d., not determined; attempts to analyze these genetic interactions were not conclusive because of the poor germination and overall spore viability of the heterozygous diploids.

To characterize the specificity of the interaction between PML39 and NUP133, we conducted a secondary screen by combining the pml39Δ mutation with most of the nucleoporin disruption available in the EUROSCARF collection. Among these, only members of the Nup84 complex, nup133Δ and nup120Δ, displayed a strong synergistic interaction with pml39Δ (Figure 1C). The other members of the Nup84 complex could not be tested because their deletion is either lethal in this background (NUP85, NUP145, and SEC13) or leads to poor sporulation and germination of the heterozygous diploids (pml39Δ/+ nup84Δ/+, and pml39Δ/+ seh1Δ/+). In addition, no synergistic interaction could be scored between pml39Δ and nup60Δ, sac3Δ or nup159-1 mutant strains (see Supplemental Figure 1, A and B) that strongly affect mRNA export (Gorsch et al., 1995; Fischer et al., 2002). This suggests that alteration of the mRNA export process is not sufficient to induce a synergistic interaction with pml39Δ. Finally, the nup133-ΔN separation-of-function mutant that only affects NPC distribution (Doye et al., 1994) did not show any genetic interaction with the PML39 deletion. This indicates that Pml39, although functionally linked to the Nup84 complex, is unlikely to be involved in this process. Indeed, NPC distribution is not altered in pml39Δ cells (our unpublished data).

Pml39 Is Associated with a Subset of Nuclear Pore Complexes

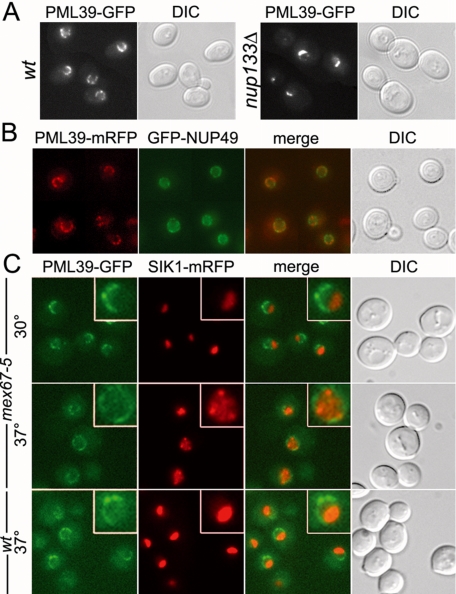

In agreement with the previously annotated nuclear envelope localization of Pml39-GFP (Huh et al., 2003), fluorescence analysis of a similarly constructed PML39-GFP strain revealed a perinuclear staining (Figure 2A, left). This GFP fusion seemed to be functional because, unlike nup133Δ pml39Δ, the growth properties of nup133Δ PML39-GFP were comparable with those of nup133Δ (our unpublished data). To determine whether Pml39 is associated with nuclear pores, we used the classical assay of NPCs clustering in nup133Δ cells (Doye et al., 1994). As shown in Figure 2A (right), nup133Δ PML39-GFP cells displayed a dot-like staining characteristic of NPC clusters that occur in nup133Δ cells, indicating that Pml39 behaves as an NPC-associated protein. However, the Pml39-GFP staining was not continuous throughout the nuclear envelope in the wild-type context, and NPC aggregates labeled by the Pml39-GFP fusion in nup133Δ cells seemed to be less extended compared with the aggregates classically observed with other GFP-tagged nucleoporins.

Figure 2.

Pml39 is associated with a subset of nuclear pore complexes. (A) PML39-GFP (wt) and nup133Δ PML39-GFP strains were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Differential interference contrast (DIC) images are also shown. (B) The PML39-mRFP strain transformed with a GFP-Nup49-expressing plasmid was analyzed for localization of Pml39 relative to nuclear pores. (C) PML39-GFP SIK1-mRFP-expressing strains either wt or carrying the mex67-5 mutation were grown at 30°C or shifted to 37°C for 30 min and examined for Pml39-GFP localization relative to the nucleolus (SIK1-mRFP). Insets show magnifications of typical nuclei. Overlay image of mRFP and GFP signals (merge) and DIC are also shown.

To further characterize the NPC localization of Pml39, we constructed a PML39-mRFP strain and transformed it with a reporter plasmid encoding a fusion between GFP and the Nup49 nucleoporin. As shown in Figure 2B, Pml39-mRFP localization seemed to be restricted to a limited region of the nuclear envelope (NE), whereas the Nup49 staining was homogeneous throughout the whole nuclear periphery. Observation of a strain expressing, in addition to Pml39-GFP, the nucleolar protein Sik1 tagged with mRFP (Huh et al., 2003) revealed that Pml39 was only present in the portion of the nuclear envelope opposite to the nucleolus (Figure 2C). Such a U-shaped distribution within the nuclear envelope has already been reported for a few NPC-associated proteins, including Mlp1 and Mlp2 (Galy et al., 2004). Observation of Pml39-mRFP localization in MLP1-GFP or MLP2-GFP strains indicated that these proteins indeed colocalize within a subset of NPCs (Figure 6B, insets). Consistently, in a nup133Δ context, an Mlp2-GFP fusion localized within NPC aggregates with a similar pattern compared with Pml39-GFP (see Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 6.

Pml39 form nuclear foci upon NUP60 deletion. (A) Fluorescence microscopy analysis of PML39-GFP nup60Δ cells expressing either Spc42-mRFP (SPBs) or Sik1-mRFP (nucleolus). (B) The localization of GFP-tagged Mlp1, Mlp2, Nab2, Npl3, Msl5, or Pml1 was analyzed in PML39-mRFP nup60Δ cells. Insets show the localization of the GFP-tagged protein and of Pml39-mRFP in a wt context. Overlay images of GFP, mRFP signals and differential interference contrast (DIC) are shown.

In an attempt to disrupt this restricted localization, we took advantage of the mex67-5 mutation that induces nucleolar disintegration at restrictive temperature (Segref et al., 1997). In mex67-5 SIK1-mRFP PML39-GFP cells shifted for 30 min to 37°C, Pml39-GFP redistributed throughout the whole nuclear envelope, concomitantly with the nucleolar disruption, leading to the appearance of intranuclear Sik1-mRFP spots (Figure 2C). Hence, Pml39 nucleolar exclusion and retention in the chromatin neighboring area are dynamic processes.

Pml39 Is Anchored to NPCs through the Nup60/Mlp1-2 Pathway

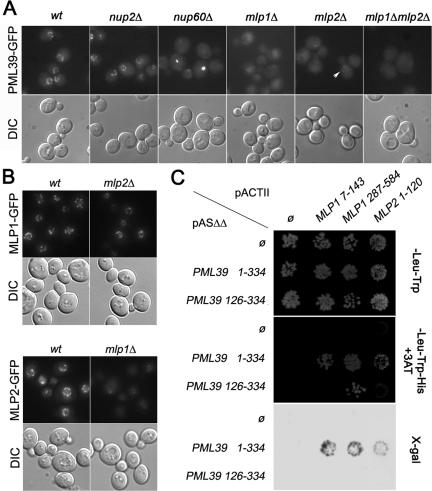

To identify the nuclear pore components involved in the targeting of Pml39 to the NPC, we analyzed Pml39-GFP localization in various nucleoporin mutant strains. Mlp1 and Mlp2 were good candidates because they exhibit, like Pml39, a restricted NPC localization. As shown in Figure 3A, Pml39-GFP was lost from the nuclear envelope in mlp1Δ cells. A less pronounced phenotype was observed in a mlp2Δ background (arrowhead), whereas the mlp1Δ mlp2Δ double mutant also exhibited a total mislocalization of the protein. The differential effect of MLP1 and MLP2 deletions on Pml39-GFP localization prompted us to investigate the localization of Mlp1-GFP and Mlp2-GFP in mlp2Δ and mlp1Δ backgrounds, respectively. Whereas MLP2 deletion did not affect Mlp1-GFP localization, the level of Mlp2-GFP present at the nuclear periphery was strongly reduced in mlp1Δ cells (Figure 3B). This may explain why MLP1 deletion more efficiently mislocalizes Pml39 from the nuclear envelope, compared with the mlp2Δ context where Mlp1 is still able to recruit Pml39.

Figure 3.

Pml39 is anchored to NPCs through interaction with Mlp1 and Mlp2. (A) PML39-GFP localization was examined in wt, nup100Δ, nup2Δ, nup60Δ, mlp1Δ, mlp2Δ, and mlp1Δ mlp2Δ backgrounds. (B) Mlp1-GFP and Mlp2-GFP localizations were examined in isogenic wt and mlp2Δ or mlp1Δ background, respectively. DIC images are also shown. (C) Two-hybrid interaction of Pml39 and Mlp1/Mlp2. CG1945 cells transformed with pASΔΔ bait vectors either empty (Ø) or encoding full-length Pml39 (aa 1–334) or its C-terminal moiety (aa 126–334) were mated with Y-187 cells transformed with pACTII prey vectors either empty (Ø) or encoding the indicated domains of Mlp1 or Mlp2. Diploids were grown on SC-Leu-Trp (top) or SC-Leu-Trp-His supplemented with 5 mM 3-aminotriazole (middle). Cells grown on SC-Leu-Trp plates were replicated on nitrocellulose membrane for β-galactosidase assay (bottom).

Mlp1 and Mlp2 are anchored to nuclear pores through interaction with Nup60 (Feuerbach et al., 2002; Galy et al., 2004). Consistently, in nup60Δ cells, Pml39-GFP staining was strongly reduced at the nuclear envelope and concentrated in one or two foci (Figure 3A; see below). In contrast, Pml39-GFP targeting to the nuclear periphery was not affected in the other nucleoporin mutants assayed, including nup2Δ, pom34Δ, pom152Δ, nup100Δ, nup157Δ, and nup170Δ (Figure 3A; our unpublished data). Finally, PML39 deletion did not affect the nuclear envelope localization of Nup133-GFP, Nup49-GFP, Nup60-GFP, Mlp1-GFP, or Mlp2-GFP fusions (our unpublished data). Together, these data demonstrate that Pml39 is a peripheral NPC-associated protein physically anchored to their nuclear side by Mlp1 and Mlp2.

Interactions between Pml39 and Mlp1/Mlp2

To identify potential partners of Pml39, we used full-length Pml39 as a bait to screen a yeast genomic library by the two-hybrid technique (Fromont-Racine et al., 1997). Strikingly, out of 34 recovered genomic inserts able to mediate interaction with Pml39, most encoded N-terminal domains of either Mlp1 (14 clones, corresponding to 7 distinct fragments) or Mlp2 (13 clones, corresponding to 3 overlapping inserts). The only other candidate identified in the screen more than twice was Nup157 (4 clones, corresponding to 3 overlapping fragments). Because this nucleoporin has been recently identified in close physical relationship with the Nup84 complex (Lutzmann et al., 2005), it may represent an NPC component physically or functionally linked to Pml39. However, because NUP157 deletion affects neither Pml39-GFP localization nor the viability of pml39Δ cells (our unpublished data), the relevance of this interaction was not further investigated.

Sequence analysis of the recovered Mlp1-2 inserts revealed two minimal domains of Mlp1 (N1, aa 7–143; N2, aa 287–584) and one domain of Mlp2 (aa 1–120) required for Pml39 interaction (Figure 3C). Conversely, to identify the regions of Pml39 required for Mlp proteins binding, N-terminal (aa 1–125) and C-terminal (aa 126–334) portions of Pml39, defined with help of the DOMCUT software (Suyama and Ohara, 2003), were cloned in the two-hybrid bait vector. Only a weak interaction was found between the C-terminal moiety of Pml39 and the Mlp1 287-584 (N2) domain (Figure 3C). In conclusion, this two-hybrid analysis demonstrates that Pml39 may bind Mlp1-2 by two different manners: the interaction with the extreme N-terminal region of Mlp1 (N1) or Mlp2 requires the whole Pml39 protein, whereas the more internal (N2) domain of Mlp1 weakly interacts with the C-terminal region of Pml39. However, the later interaction is not sufficient for Pml39 localization, because a fusion of the C-terminal moiety of Pml39 with GFP is not targeted to the nuclear envelope (our unpublished data).

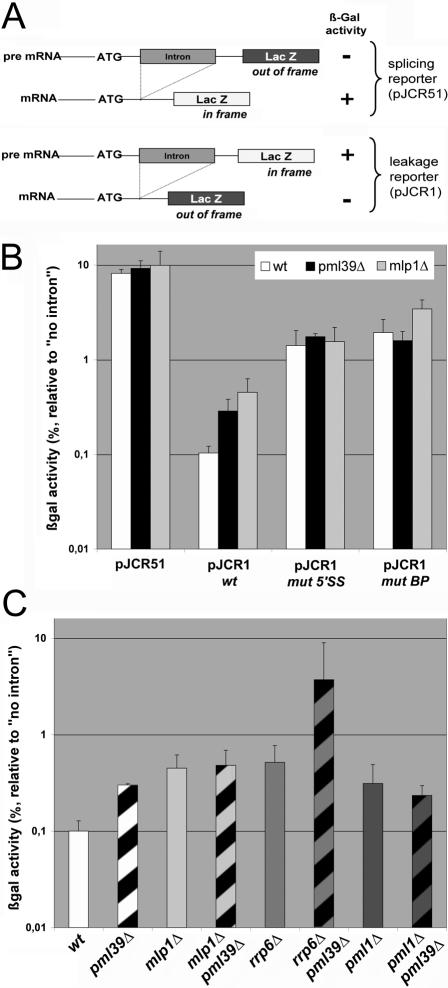

PML39 Deletion Causes Unspliced mRNA Leakage from the Nucleus

Perinuclear Mlp1-2 have been reported to be involved in a variety of nuclear processes, including definition of transcriptionally inactive nuclear subdomains, maintenance of genomic stability, and control of telomere length (Feuerbach et al., 2002; Hediger et al., 2002). More recently, Mlp1-2 have been reported to be involved in a quality control step before the export of mRNPs (Green et al., 2003; Galy et al., 2004; Vinciguerra et al., 2005). In particular, MLP1 deletion, although not affecting splicing or bulk mRNA export, gave rise to a specific leakage of intron-containing mRNAs out of the nucleus. In pml39Δ mutants, FISH using oligo(dT) probes did not reveal any global nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA (our unpublished data). To determine whether Pml39 could be involved in unspliced mRNA retention, pml39Δ cells were transformed with reporter constructs previously used to monitor this process (Legrain and Rosbash, 1989; Rain and Legrain, 1997) (Figure 4A). In the splicing reporter (pJCR51), an intron disrupts the reading frame of the LacZ coding sequence, and only spliced mRNAs can be translated into a functional enzyme (Figure 4A, top). β-Galactosidase activity, normalized to the activity obtained with an intron-less control pLGSD5 plasmid, therefore, reflects the extent of splicing. In cells transformed with the unspliced mRNA leakage reporter plasmid (pJCR1), LacZ translation only occurs in the absence of splicing (Figure 4A, bottom). Normalized β-galactosidase activity thus reflects the export of unspliced mRNAs. This analysis revealed that neither the expression of the control intronless reporter (our unpublished data), nor the splicing process (Figure 4B, pJCR51) is significantly affected by PML39 deletion. In contrast, the pJCR1 leakage reporter indicates that unspliced mRNA are exported and translated into β-galactosidase in pml39Δ cells to significant levels compared with wild-type (wt) cells (Figure 4B). The extent of pre-mRNA leakage was similar to the one occurring in an isogenic mlp1Δ strain (Figure 4B), indicating that Pml39 is also specifically involved in the nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs.

Figure 4.

PML39 deletion gives rise to a pre-mRNA leakage phenotype. (A) Schematic representation of the splicing (pJCR51) and leakage (pJCR1) reporters. Adapted from Rain and Legrain (1997). (B) Quantification of pre-mRNA splicing and leakage in wt, pml39Δ, and mlp1Δ mutants. Cells were transformed with pJCR51 or with pJCR1 either wt or mutated in its 5′ splicing site (mut 5′SS) or branchpoint (mut BP). For each construct, the percentage of β-galactosidase activity relative to the one obtained with the pLGSD5 intron-less control plasmid is represented. Values represent the means and standard deviations from five independent experiments. (C) pre-mRNA leakage in different mutant strains. wt, pml39Δ, mlp1Δ, mlp1Δ pml39Δ, rrp6Δ, rrp6Δ pml39Δ, pml1Δ, and pml1Δ pml39Δ isogenic strains carrying the pJCR1 wt reporter construct were assessed for pre-mRNA leakage as in B. Values arise from three independent experiments, and standard deviations are indicated.

Pioneer studies demonstrated that nuclear retention of pre-mRNA depends upon cis-elements within both the 5′ splicing site (5′SS) and the intron BP (Legrain and Rosbash, 1989). Accordingly, leakage of pre-mRNAs with weakened 5′SS or BP sequences is significantly enhanced in wt cells (Rain and Legrain, 1997; Figure 4B). It is noteworthy that the extent of leakage of these mutated splicing reporters was not increased further in pml39Δ cells compared with wt cells (Figure 4B). This suggests that PML39-mediated mRNA retention relies on the integrity of both 5′ splicing site and branchpoint. In our genetic background, only a modest, but statistically insignificant increase in mRNA leakage was observed with the mutBP reporter in mlp1Δ cells. This contrasts with previous studies, in which an additive effect of the mlp1Δ mutation on the mutBP reporter was observed, leading to the proposal that MLP1-mediated pre-mRNA retention is independent from an intact branchpoint (Galy et al., 2004). This discrepancy may reflect quantitative differences attributable to different genetic backgrounds. Indeed, the extent of the mlp1Δ leakage phenotype was slightly weaker in our study compared with the previously reported study. Consistently, although deletion of PRP18, which encodes a factor required for splicing as well as pre-mRNA retention, was reported to be lethal in a mlp1Δ mutant background (Galy et al., 2004), both prp18Δ mlp1Δ and prp18Δ pml39Δ strains were fully viable in our genetic background.

Pml39, Mlp1, and Pml1 Are Involved in a Common Pre-mRNA Retention Pathway

Unspliced mRNA retention requires perinuclear Mlp1 (Galy et al., 2004) and a nucleoplasmic protein, Pml1 (Dziembowski et al., 2004). To determine whether Pml39 is involved in the same mRNA retention pathway as these factors, leakage was assayed in strains combining these mutations. mlp1Δ pml39Δ as well as pml1Δ pml39Δ double mutants did not exhibit an enhanced leakage compared with single mutants, demonstrating that Pml39, Mlp1 and Pml1 act in a common pathway of unspliced mRNA retention (Figure 4C).

The exosome subunit Rrp6 is an exonuclease involved in degradation of improper nuclear mRNAs (Hilleren et al., 2001). RRP6 deletion increases nuclear pre-mRNA levels, independently of splicing (Bousquet-Antonelli et al., 2000), and therefore leads to an apparent leakage phenotype, probably because of an overall increase in unprocessed or inaccurately processed RNAs (Galy et al., 2004; Figure 4C). As reported previously for the mlp1Δ rrp6Δ double mutant, combination of RRP6 and PML39 deletions gave rise to a synergistic effect on the levels of translated and accordingly cytoplasmic unspliced mRNAs (Figure 4C). This indicates that Pml39 is also required for retention of pre-mRNA accumulated independently of any splicing defects. On the basis of these results, we have renamed the original YML107c ORF as PML39 (for pre-mRNA leakage, 39 kDa).

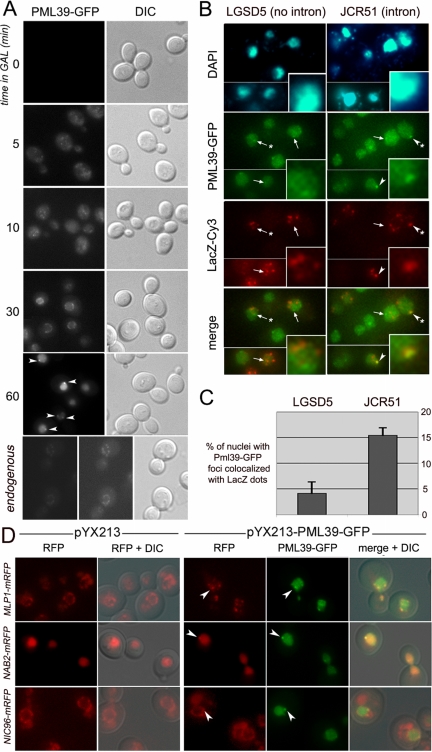

Overexpression of Pml39 Traps mRNA Transcribed from Intron-containing Genes in Discrete Nuclear Foci

Because PML39 deletion gives rise to a leakage of unspliced mRNAs, we wondered whether its overexpression could lead to an enhanced mRNA retention within the nucleus. To test this hypothesis, the PML39-GFP fusion was overexpressed under the control of the GAL1 inducible promoter in a pml39Δ strain. As shown in Figure 5A, Pml39-GFP is properly addressed to the nuclear periphery after 30 min of induction and then accumulates in the whole nucleus, with many cells exhibiting one or two Pml39-GFP foci at the nuclear periphery (≈30% after 1 h of induction). At this time point, Pml39-GFP is 10- to 40-fold overexpressed compared with the same fusion driven by its endogenous promoter as determined by quantification of fluorescence intensities.

Figure 5.

Analysis of PML39 overexpression. (A) pml39Δ cells transformed with the pYX213-PML39-GFP construct were induced in galactose for the time indicated (minutes) and analyzed for Pml39-GFP localization. Arrowheads point to Pml39-GFP foci. Cells expressing Pml39-GFP under the control of its endogenous promoter are shown as control (left, same acquisition time as for the other panels; middle, enhanced signal to show proper localization of the fusion). (B) FISH analysis of LacZ transcripts in Pml39-GFP-overexpressing cells. pml39Δ cells transformed with pYX214-PML39-GFP and either pLGSD5 (intronless LacZ reporter) or pJCR51 (intron-containing LacZ reporter) were induced for 2 h in galactose and analyzed for localization of LacZ transcripts by FISH using Cy3-conjugated probes specific to the LacZ sequences. GFP and Cy3 images are two-dimensional projections from z-stacks. DNA staining of the nuclei (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) as well as overlay images of GFP and Cy3 signals (merge) are shown. Arrowheads and arrows respectively point to Pml39-GFP foci containing or not LacZ transcripts. Insets (bottom right corners) show a threefold magnification of nuclei exhibiting typical Pml39-GFP and LacZ transcripts localizations (indicated by a star on the original image). (C) Quantification of the colocalization events from B. The number of nuclei displaying a Pml39-GFP dot merged with one of the LacZ foci was counted among nuclei exhibiting detectable signals for both species. The values represents the means and standard deviations obtained from two independent experiments; total numbers of counted cells were 285 (pLGSD5) and 363 (pJCR51). (D) Analysis of Pml39-containing foci. Strains expressing mRFP-tagged versions of Mlp1, Nab2, or Nic96 were transformed with either pYX213 or pYX213-PML39-GFP and Pml39 overexpression was induced in galactose for 1 h. Overlay images of GFP, mRFP signals, and differential interference contrast (DIC) are shown (merge + DIC). Arrowheads point to Pml39-GFP foci.

Then, plasmids carrying the LacZ gene containing or not an artificial intron upstream of its coding sequence (pLGSD5, without intron; pJCR51, with intron) were used to monitor the localization of specific transcripts by FISH. Cells were induced for production of both the LacZ transcripts and Pml39-GFP by a 2-h shift in galactose-containing medium. As reported previously (Long et al., 1995; Vinciguerra et al., 2005), LacZ mRNAs accumulate within a few nucleoplasmic foci probably corresponding to the sites of transcription (Figure 5B). Interestingly, the Pml39-GFP foci were found to colocalize with the LacZ mRNA-containing foci, an event that was significantly favored in the case of transcripts issued from intron-containing constructs (Figure 5, B and C). Additional LacZ-dependent FISH foci were frequently seen outside of the Pml39-GFP clusters, a fact that may reflect the presence of additional intranuclear retention sites or nondetectable Pml39-GFP clusters. In conclusion, overexpression of Pml39-GFP leads to its accumulation within discrete nuclear foci that are able to trap preferentially mRNAs issued from intron-containing genes.

Pml39 Nuclear Foci Contain Mlp Nucleoporins and the mRNP Component Nab2

To determine whether Pml39-GFP was able to trap specific proteins in the foci occurring upon its overexpression, the protein expression was induced in strains carrying various mRFP fusions. As shown in Figure 5D, Pml39 overexpression disturbed the nuclear envelope localization of Mlp1 and provoked its accumulation in the nuclear Pml39-GFP foci. A similar observation was made in Nab2, an mRNA export factor shown to associate with Mlp1 (Green et al., 2003), which was also partially recruited to the Pml39-GFP foci upon Pml39 overexpression. This last phenomenon was not observed in all cells, possibly reflecting a dependence on the level of Pml39 overexpression (Figure 5D). The recruitment of Mlp1 and Nab2 to Pml39 foci was specific because an unrelated nucleoporin, Nic96, was unaffected by the Pml39 overexpression and was not recruited into the Pml39-GFP foci. This result further indicates that these foci do not correspond to NPC aggregates (Figure 5D, bottom).

As mentioned above, Pml39-GFP also accumulates within bright foci in nup60Δ cells (Figure 3A). Analysis of various strains deleted for NUP60 and coexpressing a PML39-mRFP fusion together with different nuclear GFP fusions confirmed this localization and further indicated that the Pml39 foci are localized at the nuclear periphery (Figure 6B). These foci did not colocalize with the nucleolus labeled with Sik1-mRFP (Figure 6A). Although functional links have recently been suggested between spindle pole bodies (SPBs) and NPCs (Fischer et al., 2004; Niepel et al., 2005), the Pml39-GFP foci did not merge with the Spc42-mRFP labeled SPBs (Figure 6A).

These Pml39 foci were reminiscent to the Mlp1-2 localization in nup60Δ cells (Feuerbach et al., 2002; Galy et al., 2004) and indeed colocalized with the Mlp1-GFP and Mlp2-GFP foci occurring upon NUP60 deletion (Figure 6B). Such a localization was recently demonstrated to be shared by another Mlp1-2-anchored protein, Mad1 (Scott et al., 2005). In contrast, although the NE localization of another Mlp-interacting protein, the ubiquitin-like protease Ulp1 (Zhao et al., 2004), was altered in nup60Δ cells, Ulp1-GFP was not enriched in the Pml39-mRFP foci (our unpublished data). This may reflect its previously reported degradation (Zhao et al., 2004), and/or the presence of additional Ulp1 binding sites at the NPC (Panse et al., 2003). Finally, a fraction of Nab2-GFP was also recruited within the Pml39-mRFP foci. In contrast, no detectable recruitment of other mRNA export factors components (Yra1 and Npl3) or known pre-mRNP retention factors (Msl5 and Pml1) could be observed (Figure 6B; our unpublished data).

In summary, upon its overexpression or its mislocalization due to NUP60 deletion, Pml39 localizes within perinuclear foci containing Mlp1-2 and Nab2. This result emphasizes the link existing between Mlp1-2 and Pml39 and further strengthens the connection between mRNPs assembly factors—such as Nab2—and the Mlp–Pml39 complex.

PML39 Deletion Bypasses the Requirement for mRNPs Assembly Factors

The previous result suggested a link between Pml39 and mRNPs components. Interestingly, recent data established that MLP1 or MLP2 deletions can rescue the temperature-sensitive phenotypes of mRNPs mutants such as GFP-yra1-8 or ΔN-nab2 alleles (Vinciguerra et al., 2005). We therefore analyzed the effect of PML39 deletion on the growth properties of both mutants. In the pml39Δ mutant, the thermosensitive GFP-yra-1-8 mutation was suppressed, allowing growth of the cells at the restrictive temperatures of 34 and 37°C, to the same extent as in a mlp2Δ mutant (Figure 7A). Similarly, growth of the ΔN-nab2 mutant was substantially improved at 30 and 37°C in the pml39Δ context (Figure 7B). The PML39 deletion is therefore able to rescue sublethal phenotypes of mRNPs mutants, indicating that it can bypass the requirement for normal mRNPs assembly factors.

Figure 7.

PML39 deletion rescues the temperature-sensitive phenotypes of GFP-yra1-8 and ΔN-nab2 mutants. (A) The YRA1 shuffle strains as such or deleted for PML39 or MLP2 were transformed with the LEU2-containing wt YRA1 or GFP-yra1-8 plasmids. Transformants were spotted as fivefold dilutions on 5-fluoroorotic acid to select against the wt pURA3-YRA1 plasmid or on–Leu as control. Plates were incubated at 25, 34, or 37°C. (B). The NAB2 shuffle strains as such or deleted for PML39, MLP1, or MLP2 were transformed with the LEU2-containing wt NAB2 or ΔN-nab2 plasmids. Growth of the transformants was analyzed as in A.

DISCUSSION

Asymmetric NPC Anchoring of Pml39 Is Mediated by Mlp1-2

Using a systematic synthetic lethal screen, we have identified a novel NPC-associated protein that we named Pml39, because the deletion of the corresponding gene affects pre-mRNA retention. Our data demonstrate a physical connection between Pml39 and Mlp1-2: 1) these proteins share a restricted U-shaped NPC localization opposite to the nucleolus and colocalize into perinuclear foci upon NUP60 deletion; 2) overexpression of Pml39 leads to its nuclear accumulation, a feature anticipated for a nucleoporin localized on the nuclear side of the NPCs; under these conditions, Pml39 accumulates within intranuclear foci able to specifically recruit a fraction of Mlp1; 3) the N-terminal domains of Mlp1 and Mlp2 were frequently found in a two-hybrid screen using Pml39 as a bait (27 of 34 candidates); 4) deletion of Mlp1, and to a lesser extent of Mlp2, leads to the mislocalization of Pml39, whereas neither Mlp1 nor Mlp2 is mislocalized in pml39Δ cells, indicating that Mlp1-2 anchor Pml39 to NPCs. Unlike Mlp1 and Mlp2, Pml39 was not previously identified in proteomic studies of the yeast NPCs (Rout et al., 2000). Its Mlp-dependent association with NPCs might thus be either transient or unstable under biochemical purification conditions. Indeed, we were not so far able to confirm these interactions under classical immunoprecipitation conditions. Nevertheless, our data establish that Pml39 is anchored to a subset of NPCs, through interaction with the N-terminal domains of Mlp1 and Mlp2.

Upon nucleolar fragmentation, Pml39, and most likely its NPC-anchoring determinants Mlp1-2, are redistributed throughout the whole nuclear periphery. This could reflect either the dynamic exchange of these proteins between NPCs or the redistribution of a specific subset of NPCs by lateral diffusion. The fact that Mlp1 remains asymmetrically localized in a pml39Δ mutant (our unpublished data) indicates that Pml39 is not directly involved in this process. However, recent studies have established functional links between NPC constituents, including Mlps, and the transcriptional machinery (Vinciguerra and Stutz, 2004, and references therein). NPCs facing the transcribed chromatin may thus be specialized in the export of specific mRNPs and subsequently in the quality control steps required before their export.

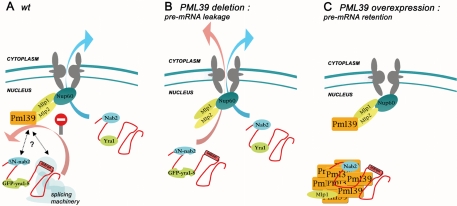

Plm39 Is an Upstream Effector of Mlp1 and Mlp2 in the Retention of Improper mRNP Particles

In addition to its Mlp-dependent NPC anchoring, our data demonstrate that Pml39 is involved in the Mlp-dependent pre-mRNPs retention process (Figure 8): 1) both PML39 and MLP1 deletions lead to similar levels of unspliced mRNA translation that are enhanced in the absence of Rrp6, a nuclear component of the exosome. Conversely, combined deletion of PML39 and MLP1 does not increase leakage, suggesting that they act in a common pathway of pre-mRNA retention; 2) both Pml39 and Mlp1 overexpression lead to the specific retention of mRNA transcribed from intron-containing genes (Galy et al., 2004; this study); 3) loss of Mlp1, Mlp2, or Pml39 proteins notably improves the survival of mRNP assembly mutants such as GFP-yra1-8 or ΔN-nab2. This suggests that the Mlp/Pml39-dependent inhibition of improper mRNP export becomes fatal when the proportion of such mRNPs is severely increased. It is noteworthy that deletion of PML39 allows the survival of GFP-yra1-8 cells at 37°C, a feature shared by Mlp2 but not Mlp1 (Vinciguerra et al., 2005; this study). Because Mlp2 is partially mislocalized in mlp1Δ cells (Figure 3), Mlp2 could be the main actor in a Yra1-sensitive mRNP surveillance process. In contrast, Mlp2 does not seem to affect nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs (Galy et al., 2004). Accordingly, our data indicate that Pml39 recapitulates both the Mlp1- and Mlp2-dependent phenotypes in terms of mRNA surveillance. In contrast, Pml39 does not seem to play a role in the Ulp1-dependent functions of Mlp1-2, such as clonal lethality caused by increased levels of 2μ circle DNA or defects in DNA repair (Zhao et al., 2004). In particular, unlike Mlp1-2, its disruption does not lead to the formation of nibbled colonies (our unpublished data). Considering the recently demonstrated SUMOylation of Ku70 (Zhao and Blobel, 2005), the other so far-reported Mlp functions in telomere length regulation, clustering, or silencing (Feuerbach et al., 2002; Hediger et al., 2002) may also involve the desumoylating enzyme Ulp1 rather than Pml39.

Figure 8.

Model for Pml39 function in improper mRNP retention in the nucleus. The mRNP trafficking is represented in the wt situation (A), upon PML39 deletion (B) or overexpression (C). Black dotted arrows point to potential interactions between Pml39 and the mRNP or the splicing machinery.

As anticipated for a gene solely involved in a checkpoint function, PML39 deletion does not affect cell growth or viability in a wild-type context. In addition, despite the enhanced levels of unspliced cytoplasmic mRNA in pml39Δ rrp6Δ cells, genetic analyses did not reveal any synergistic interaction between pml39Δ and rrp6Δ. Similarly, PML39 deletion did not impair the viability or the growth properties of NMD mutants cells (xrn1Δ, upf1Δ, upf2Δ, and upf3Δ; see Supplemental Figure 1C), indicating that cytoplasmic accumulation of unspliced mRNA occurring in pml39Δ cells does not affect cell viability when NMD is compromised. Yet, PML39 function can be revealed in specific genetic backgrounds, such as (as unraveled in our screen) alteration of the Nup84 complex integrity. In this respect, our nup133Δ synthetic lethal screen identified, besides nucleoporins, double-strand break metabolism genes (Loeillet et al., 2005), and mRNA export factors (Sac3, Thp1, and THO complex genes; our unpublished data), several components of mRNA decay pathways including Rrp6. This suggests that affecting at the same time the bulk mRNA export process (nup133Δ) and a quality control step in mRNP export (pml39Δ) or decay (rrp6Δ) may be deleterious for the cell as the ratio of proper mRNAs reaching the cytoplasm becomes limiting. However, NUP133 deletion is in contrast not synergistic with the deletion of another pre-mRNA retention factor, PML1. Because combination of nucleoporin mutations often gives rise to synthetic lethality, the association of Pml39 with NPCs might also contribute to its genetic interaction with NUP133. Yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying these genetic interactions are likely to be more complex, because PML39 deletion does not affect the viability of nup159-1 mutants, which also affects a nucleoporin involved in mRNA export.

Molecular Links between Pml39 and the mRNP Retention Pathway

Although we could demonstrate that Pml39 acts as an upstream effector of Mlp1-2 in their mRNA quality control function, the molecular mechanisms ensuring the recognition and trapping of improper mRNPs still remain to be unraveled. Because RNA binding motifs have not been found in Pml39 amino acid sequence, mRNA-associated proteins are likely to serve as landmarks to recruit Pml39 onto improper mRNPs. In this respect, the identification of Nab2 in intranuclear Pml39-containing foci is intriguing. Although our two-hybrid screen revealed that Pml39 interacts with the N-terminal domains of Mlp1 and Mlp2, Nab2 binds directly to the C-terminal domain of Mlp1 (Green et al., 2003). Mlp1 may therefore bind simultaneously Nab2 and Pml39 and thus mediate Nab2 recruitment in Plm39-containing foci.

Remarkably, the C-terminal region of Pml39 contains a short domain (aa 173–214) displaying 54% similarity with the unusual WW-domain of human HYPA/FBP11, a protein–protein interaction motif characterized by the presence of a central block of tyrosine residues (Y189Y190 in Pml39). In HYPA/FBP11, this domain mediates the interaction with proteins of the splicing machinery containing a prolineglycine-methionine-rich motif such as SF1, the human orthologue of yeast Msl5 (Bedford et al., 1998). Such a domain may thus be involved in targeting Pml39 to unspliced mRNAs through interactions with splicing factors. In contrast, the lack of synergism between pml1Δ and pml39Δ in term of pre-mRNA retention suggests that Pml1 could directly or indirectly interact with Pml39. Although we could not so far detect any stable interaction between Pml39 and Msl5 or Pml1, more systematic biochemical and microscopic studies, performed in various mutant backgrounds, might help in the future to define the molecular link between recognition of improper mRNPs and their Pml39-mediated retention.

Besides in closely related fungi, PML39 seems to have diverged quickly. Yet, a putative orthologue, rsm1, was found in Schizosaccharomyces pombe genome. Interestingly, combination of the nonessential rsm1 and spmex67 deletions confers synthetic lethality accompanied by a severe mRNA export defect (Yoon, 2004). Although further functional studies of rsm1 will be required to validate the relevance of this hypothesis, the Pml39 protein and its functions might have been conserved through evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to F. Stutz, A. Corbett, M. Fromont-Racine, A. Jacquier, U. Nehrbass, V. Galy, O. Gadal, E. Hurt, D. Stillman, A. Spang, J. Hegemann, W.-K. Huh, and R. Tsien for reagents and/or fruitful discussion. Many thanks to A. Chadrin and O. Canli for help with synthetic lethal screening and yeast handling, to J. Sillibourne for English proofreading, to the Curie Imaging Staff, and to all members of ours laboratories for constant support and valuable comments during the course of this work. Ours laboratories were supported by a collaborative program between the Institut Curie and the Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique (PIC Paramètres Epigénétiques, grants to V. D. and A. N.), the Ligue contre le Cancer (comité de Paris, to V. D.), the Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (ARC, to V. D.). B. P. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from ARC.

This article was published online ahead of print in MBC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E05–06–0527) on September 14, 2005.

Abbreviations used: FISH, in situ fluorescence hybridization; mRNP, messenger ribonucleoparticle; NPC, nuclear pore complex; SPB, spindle pole body.

The online version of this article contains supplemental material at MBC Online (http://www.molbiolcell.org).

References

- Bai, S. W., Rouquette, J., Umeda, M., Faigle, W., Loew, D., Sazer, S., and Doye, V. (2004). The fission yeast Nup107–120 complex functionally interacts with the small GTPase Ran/Spi1 and is required for mRNA export, nuclear pore distribution, and proper cell division. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 6379–6392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, M. T., Reed, R., and Leder, P. (1998). WW domain-mediated interactions reveal a spliceosome-associated protein that binds a third class of proline-rich motif: the proline glycine and methionine-rich motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10602–10607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousquet-Antonelli, C., Presutti, C., and Tollervey, D. (2000). Identification of a regulated pathway for nuclear pre-mRNA turnover. Cell 102, 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doye, V., Wepf, R., and Hurt, E. C. (1994). A novel nuclear pore protein Nup133p with distinct roles in poly(A)+ RNA transport and nuclear pore distribution. EMBO J. 13, 6062–6075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziembowski, A., Ventura, A. P., Rutz, B., Caspary, F., Faux, C., Halgand, F., Laprevote, O., and Seraphin, B. (2004). Proteomic analysis identifies a new complex required for nuclear pre-mRNA retention and splicing. EMBO J. 23, 4847–4856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerbach, F., Galy, V., Trelles-Sticken, E., Fromont-Racine, M., Jacquier, A., Gilson, E., Olivo-Marin, J. C., Scherthan, H., and Nehrbass, U. (2002). Nuclear architecture and spatial positioning help establish transcriptional states of telomeres in yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T., Rodriguez-Navarro, S., Pereira, G., Racz, A., Schiebel, E., and Hurt, E. (2004). Yeast centrin Cdc31 is linked to the nuclear mRNA export machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, T., Strasser, K., Racz, A., Rodriguez-Navarro, S., Oppizzi, M., Ihrig, P., Lechner, J., and Hurt, E. (2002). The mRNA export machinery requires the novel Sac3p-Thp1p complex to dock at the nucleoplasmic entrance of the nuclear pores. EMBO J. 21, 5843–5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromont-Racine, M., Rain, J. C., and Legrain, P. (1997). Toward a functional analysis of the yeast genome through exhaustive two-hybrid screens. Nat. Genet. 16, 277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galy, V., Gadal, O., Fromont-Racine, M., Romano, A., Jacquier, A., and Nehrbass, U. (2004). Nuclear retention of unspliced mRNAs in yeast is mediated by perinuclear Mlp1. Cell 116, 63–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauss, R., Trautwein, M., Sommer, T., and Spang, A. (2005). New modules for the repeated internal and N-terminal epitope tagging of genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 22, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, W., and Guthrie, C. (2004). The Glc7p nuclear phosphatase promotes mRNA export by facilitating association of Mex67p with mRNA. Mol. Cell 13, 201–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsch, L. C., Dockendorff, T. C., and Cole, C. N. (1995). A conditional allele of the novel repeat-containing yeast nucleoporin RAT7/NUP159 causes both rapid cessation of mRNA export and reversible clustering of nuclear pore complexes. J. Cell Biol. 129, 939–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. M., Johnson, C. P., Hagan, H., and Corbett, A. H. (2003). The C-terminal domain of myosin-like protein 1 (Mlp1p) is a docking site for heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins that are required for mRNA export. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1010–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldener, U., Heinisch, J., Koehler, G. J., Voss, D., and Hegemann, J. H. (2002). A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hector, R. E., Nykamp, K. R., Dheur, S., Anderson, J. T., Non, P. J., Urbinati, C. R., Wilson, S. M., Minvielle-Sebastia, L., and Swanson, M. S. (2002). Dual requirement for yeast hnRNP Nab2p in mRNA poly(A) tail length control and nuclear export. EMBO J. 21, 1800–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hediger, F., Dubrana, K., and Gasser, S. M. (2002). Myosin-like proteins 1 and 2 are not required for silencing or telomere anchoring, but act in the Tel1 pathway of telomere length control. J Struct. Biol. 140, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilleren, P., McCarthy, T., Rosbash, M., Parker, R., and Jensen, T. H. (2001). Quality control of mRNA 3′-end processing is linked to the nuclear exosome. Nature 413, 538–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh, W. K., Falvo, J. V., Gerke, L. C., Carroll, A. S., Howson, R. W., Weissman, J. S., and O'Shea, E. K. (2003). Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature 425, 686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T. H., Dower, K., Libri, D., and Rosbash, M. (2003). Early formation of mRNP: license for export or quality control? Mol. Cell 11, 1129–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrain, P., and Rosbash, M. (1989). Some cis- and trans-acting mutants for splicing target pre-mRNA to the cytoplasm. Cell 57, 573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeillet, S., Palancade, B., Cartron, M., Thiery, A., Richard, G.-F., Dujon, B., Doye, V., and Nicolas, A. (2005). Genetic network interactions among replication, repair and nuclear pore deficiencies in yeast. DNA Repair 4, 459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, R. M., Elliott, D. J., Stutz, F., Rosbash, M., and Singer, R. H. (1995). Spatial consequences of defective processing of specific yeast mRNAs revealed by fluorescent in situ hybridization. RNA 1, 1071–1078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M. S., McKenzie, A., 3rd, Demarini, D. J., Shah, N. G., Wach, A., Brachat, A., Philippsen, P., and Pringle, J. R. (1998). Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 14, 953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutzmann, M., Kunze, R., Stangl, K., Stelter, P., Toth, K. F., Bottcher, B., and Hurt, E. (2005). Reconstitution of Nup157 and Nup145N into the Nup84 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18442–18451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niepel, M., Strambio-de-Castillia, C., Fasolo, J., Chait, B. T., and Rout, M. P. (2005). The nuclear pore complex-associated protein, Mlp2p, binds to the yeast spindle pole body and promotes its efficient assembly. J. Cell Biol. 170, 225–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panse, V. G., Kuster, B., Gerstberger, T., and Hurt, E. (2003). Unconventional tethering of Ulp1 to the transport channel of the nuclear pore complex by karyopherins. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 21–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rain, J. C., and Legrain, P. (1997). In vivo commitment to splicing in yeast involves the nucleotide upstream from the branch site conserved sequence and the Mud2 protein. EMBO J. 16, 1759–1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. S., Dargemont, C., and Stutz, F. (2004). Nuclear export of RNA. Biol. Cell 96, 639–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Navarro, S., Fischer, T., Luo, M. J., Antunez, O., Brettschneider, S., Lechner, J., Perez-Ortin, J. E., Reed, R., and Hurt, E. (2004). Sus1, a functional component of the SAGA histone acetylase complex and the nuclear pore-associated mRNA export machinery. Cell 116, 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rout, M. P., Aitchison, J. D., Suprapto, A., Hjertaas, K., Zhao, Y., and Chait, B. T. (2000). The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 148, 635–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutz, B., and Seraphin, B. (2000). A dual role for BBP/ScSF1 in nuclear pre-mRNA retention and splicing. EMBO J. 19, 1873–1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott, R. J., Lusk, C. P., Dilworth, D. J., Aitchison, J. D., and Wozniak, R. W. (2005). Interactions between Mad1p and the nuclear transport machinery in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 4362–4374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segref, A., Sharma, K., Doye, V., Hellwing, A., Huber, J., Lührmann, R., and Hurt, E. C. (1997). Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear mRNA export binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J. 16, 3256–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siniossoglou, S., Wimmer, C., Rieger, M., Doye, V., Tekotte, H., Weise, C., Emig, S., Segref, A., and Hurt, E. C. (1996). A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell 84, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, K., and Hurt, E. (2000). Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with Mex67p and is required for mRNA export. EMBO J. 19, 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, K., et al. (2002). TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature 417, 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama, M., and Ohara, O. (2003). DomCut: prediction of inter-domain linker regions in amino acid sequences. Bioinformatics 19, 673–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra, P., Iglesias, N., Camblong, J., Zenklusen, D., and Stutz, F. (2005). Perinuclear Mlp proteins downregulate gene expression in response to a defect in mRNA. export. EMBO J. 24, 813–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinciguerra, P., and Stutz, F. (2004). mRNA export: an assembly line from genes to nuclear pores. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 16, 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth, W. P., Jiang, Y. W., and Stillman, D. J. (2003). New `marker swap' plasmids for converting selectable markers on budding yeast gene disruptions and plasmids. Yeast 20, 985–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzeler, E. A., et al. (1999). Functional characterization of the S. cerevisiae genome by gene deletion and parallel analysis. Science 285, 901–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, J. H. (2004). Schizosaccharomyces pombe rsm1 genetically interacts with spmex67, which is involved in mRNA export. J. Microbiol. 42, 32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., and Blobel, G. (2005). A SUMO ligase is part of a nuclear multiprotein complex that affects DNA repair and chromosomal organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4777–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Wu, C. Y., and Blobel, G. (2004). Mlp-dependent anchorage and stabilization of a desumoylating enzyme is required to prevent clonal lethality. J. Cell Biol. 167, 605–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.