The average patient visiting a doctor in the United States gets 22 seconds for his initial statement, then the doctor takes the lead.1 This style of communication is probably based on the assumption that patients will mess up the time schedule if allowed to talk as long as they wish to. But for how long do patients actually talk, at least initially? We found only one study, from a neurological practice, investigating this question.2 The author reported one minute and 40 seconds. We examined how long it would take outpatients at a tertiary referral centre to indicate that they have completed their story—for example, with a statement such as: “That's all, doctor!” if uninterrupted by their doctors.

Participants, methods, and results

We investigated a sequential cohort of patients from the outpatient clinic of the department of internal medicine at the university hospital in Basle. The study protocol was approved by the university's ethics committee. Inclusion criteria were sufficient knowledge of the German language, first contact with the outpatient clinic, and mental competence. We informed doctors about the purpose of the study and told patients that we were interested in their opinion concerning the service provided. We asked doctors to activate a stop watch surreptitiously at the start of the communication and press it again when patients indicated that they wanted the doctor to take the lead (for example, by saying: “What do you think, doctor?”). Patients did not know that a timer was being used. Doctors were trained for one hour in basic elements of active listening, such as waiting, use of facilitators like “hmm-hmm,” nodding, or echoing. They were told not to ask questions during the initial phase of the consultation. To comply with their consultation schedule they were advised to interrupt if a patient talked for more than five minutes.

Within three months 406 out of a total of 1137 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria; 33 were later judged as not correctly classified. Of the remaining 373, 20 patients did not give informed consent; for nine patients doctors did not register talking time; and data on talking time were lost for nine patients. We analysed spontaneous talking time in 335 patients who had been seen by 14 doctors. Of the 330 patients who provided sociodemographic data, 176 (53%) were female, mean age was 42.9 years (SD 18.2 (95% confidence interval 17 to 84) years). The sociodemographic characteristics were typical of patients seen at this hospital.3 The 11 male and three female doctors had worked a mean of 58 (26) months in the clinical field, with a mean of 38 (19) months spent in internal medicine.

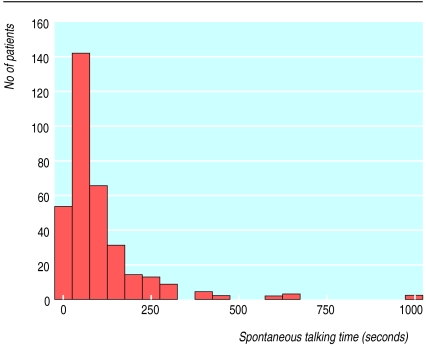

Mean spontaneous talking time was 92 seconds (SD 105 seconds; median 59 seconds; figure), and 78% (258) of patients had finished their initial statement in two minutes. Seven patients talked for longer than five minutes. In all cases doctors felt that the patients were giving important information and should not be interrupted. No other sociodemographic variable (education, income, civil status, type of employment, and sex) had a significant influence on spontaneous talking time except for age (rs=0.41; P<0.001; 17-29 years: 77 (105) seconds; 30-49 years: 92 (93) seconds; 50-87 years: 108 (114) seconds).

Comment

Doctors do not risk being swamped by their patients' complaints if they listen until a patient indicates that his or her list of complaints is complete. Even in a busy practice driven by time constraints and financial pressure, two minutes of listening should be possible and will be sufficient for nearly 80% of patients. We gathered data in a tertiary referral centre that is characterised by a selection of difficult patients with complex histories.4 Patients in less selected groups might need even less time to complete their initial statement.

Figure.

Spontaneous talking time of 331 patients at start of consultation in outpatient clinic

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues at the outpatient clinic for providing the data and the administrative staff for collecting patient questionnaires.

Footnotes

Funding: WL was supported by a grant from the Verein zur Frderung von Wissenschaft, Aus-, Weiter- und Fortbilding (VFWAWF) of the Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Basle, Switzerland.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Marvel MK, Epstein RM, Flowers K, Beckman HB. Soliciting the patient's agenda: have we improved? JAMA. 1999;281:283–287. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blau JN. Time to let the patient speak. BMJ. 1989;298:39. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martina B. [Reasons for consultation in ambulatory general internal medicine] Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 1994;83:147–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martina B, Bucheli B, Stotz M, Battegay E, Gyr N. First clinical judgment by primary care physicians distinguishes well between nonorganic and organic causes of abdominal or chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:459–465. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]