Abstract

Background

International reports highlight important impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wellbeing of youth. There is limited knowledge of the experiences and perspectives of youth, and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Examining these experiences can help us identify existing gaps in support and which policy adjustments, resources, and programs are needed to enhance the wellbeing of youth and families in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Methods

In this qualitative descriptive study Canadian youth (11-18year) and their parents (≥ 18year) who participated in a previous national survey looking at public perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic, were invited to participate. Youth and their parents across all ten Canadian provinces were interviewed separately between June and September 2022. Interview guides were developed and refined iteratively with experts on child development along with youth and parent partners. Responses we coded inductively and a qualitative descriptive analysis was performed. We conducted and reported this study according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist.

Results

We interviewed 14 youth-parent dyads (28 interviews). Most participants identified as Black, Indigenous, or persons of colour (18/ 28, 64%) and as cis-gender women/girls (15/28, 54%); the median ages were 14 (interquartile range (IQR) 12–16) and 46 (IQR 40–50), for youth and parents respectively. All parents (14/14, 100%) were married. We generated four topic summaries in the data, relevant to youth and family wellbeing throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and in the post-pandemic period: (1) connectedness (a sense of being cared for and supported), (2) motivation and drive (activating and sustaining behaviour toward a goal despite difficulties), (3) mental health (including emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing, develop fulfilling relationships, and adapting to change) and (4) coping mechanisms (strategies used to adjust to stressful events to help maintain overall wellbeing). Findings highlight negative impacts of increased isolation associated with COVID-19 pandemic and their interconnectedness. Results underscore the importance of employing integrated policies that address these complex challenges while informing the tailoring of existing policies, resources, and programs to better support and improve the well-being of youth and families as they navigate the ongoing impacts of the pandemic.

Conclusions

Canadian youth and parents in our sample provided detailed descriptions on how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted their wellbeing and the strategies they used to reduce these impacts as much as possible. There is a need for support both at-home and in-school, emphasizing the importance of having a range of programs that address challenges across all facets of youths’ lives.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12889-025-24244-4.

Keywords: Youth, Parents, Mental health, Psychology, Interviews , COVID-19, Public health

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted governments and public health officials globally to enact broad measures to protect the public. These measures included widespread closure of public institutions and implementation of physical and social distancing policies [1]. Theory and evidence suggest that COVID-19 and associated public health measures impacted children and youth wellbeing through several mechanisms [2, 3]. For instance, increased social isolation and reduced social contacts diminish protective factors (biological, psychological, and social characteristics) that help buffer the negative effects of risk factors (e.g., grief, poverty, family dysfunction) on youth’s cognitive and social development [4, 5]. Some researchers have reported increased anxiety among children and youth due to loss of familiar and cherished activities, and the absence of protective effects of connections with school [6].

Wellbeing may be conceptualized differently across individuals, groups, and communities [7]. Wellbeing is shaped by experiences and perspectives, which are, in turn, influenced by a range of factors from familial to societal [8, 9]—for children and youth to “be well” requires specific conditions to be in place that allow them to reach their full potential [10]. Adverse child experiences like abuse, poverty, or bullying [11] can have long-lasting effects across the entire life course, exacerbating existing inequalities and having damaging consequences for the health and wellbeing of children, youth, and society [12, 13]. The risks associated with adverse childhood experiences only increase in the context of a global pandemic where families are under increased stress, school closures are widespread, and physical interactions are heavily restricted [4, 13, 14].

International reports highlight the wide-ranging harm of the COVID-19 pandemic to the wellbeing of youth, including increased rates of anxiety and depression [15–17]. A survey study conducted among Canadian adults found that 49% of respondents stated their social health had worsened and that 39% of respondents experienced poorer mental and emotional health following the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. This has researchers issuing an urgent call for mental health interventions aimed at supporting youth as they return to school following the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the harms of COVID-19 are well-documented [19, 20], less is known about the experiences of youth and their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic, making it challenging to improve youth wellbeing beyond deleterious impacts of the virus. In response to this knowledge gap, we sought to answer the following research question: “What are the perceived impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wellbeing of youth and families in Canada?” To answer this question, we conducted a qualitative descriptive study with youth and parents to gain an in-depth understanding of their perceptions, behaviours, underlying drivers, and experiences regarding the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their wellbeing. We sought to identify existing gaps in support to determine the necessary policy changes, resources, and programs to improve the well-being of youth and families as they navigated a myriad of challenges with virtual schooling, social isolation, and massive disruptions in routine, all within the context of a pandemic. Results can guide the development and evaluation of policies and programs designed to support youth and families in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

We performed semi-structured parent-youth dyad interviews (N = 28 total: 14 parents, 14 youth, conducted separately) via Microsoft Teams (without video) between June and September 2022 across all ten provinces in Canada as we were unable to recruit participants from any of the territories. We used a constructivist paradigm to conceptualize this qualitative descriptive study which was conducted with approval from the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID#:#23–0039) and Dalhousie University Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID#: #2023–6538) in accordance with all institutional privacy and security protocols. This study was conducted and reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research checklist (COREQ) (Additional File 1. COREQ Checklist).

Participants

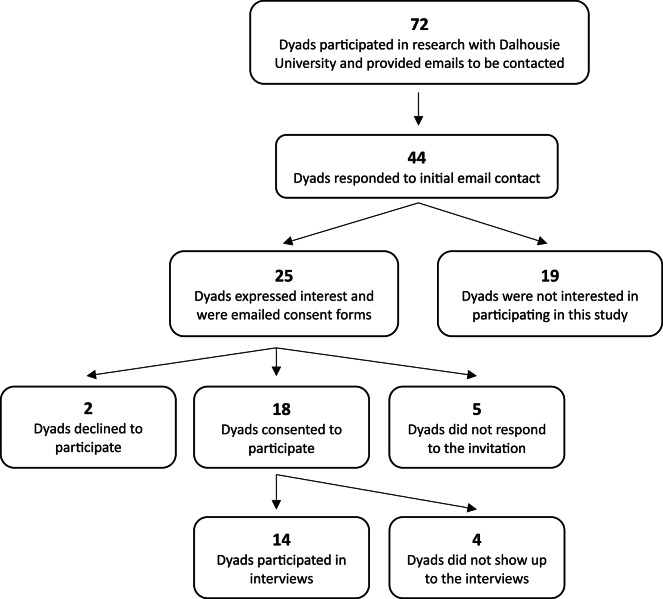

Canadian youth (11-18year) and their parent (≥ 18) who participated in a previous mixed methods project (a national, cross-sectional survey with 933 parent-youth dyads) [18] and who provided contact information for follow-up were emailed and invited to participate in an interview (Fig. 1. Recruitment Flow Chart). Recruitment occurred between May 1 and July 31 st, 2022. Eligibility criteria included: being aged 11–18 years (youth) and ≥ 18 years (parent), living in Canada at the time of the interview, and understanding and speaking English or French. If a parent had more than one eligible youth, they were asked to select the youth with the most recent birthday (parents did not need to participate with the same youth who responded to the survey in phase one). Participants were purposively sampled to ensure diversity of geographic location, sex and/or gender, and ethnicity. Dyads were provided with a $50 (Canadian dollars) gift card of their choice to compensate their time.

Fig. 1.

Recruitment Flow Chart

Interview guide

The interview guides were informed by a previous mixed-methods project and consisted of several overarching topics related to knowledge, perceptions, behaviours, underlying drivers, and experiences regarding wellbeing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic [18]. Guides were developed and refined iteratively in collaboration with youth and parent partners, child development experts (academic researchers, clinical psychologists, and social workers), and experts in qualitative research. Separate interview guides were developed for youth and parents to accommodate reading levels (guide content remained similar); the youth interview guide was designed to be straightforward and structured (with opportunities for youth to further describe experiences and perspectives), while the parent interview guide included more open-ended questions traditionally associated with semi-structured interviews. The guides were pilot tested with child development experts (N = 2) and youth partners (N = 3) (external to the research team) prior to commencing interviews. Revisions to the guides post-pilot were to improve conciseness and clarity (Additional File 2. Interview Guides).

Data collection

Two female research assistants [MS: White; LL: White] with oversight from a female qualitative researcher [SJMo: White] and sociologist [JPL: White] conducted the semi-structured interviews with parents and youth separately. Prior to each interview, the interviewer reviewed the informed consent form with the participant, and the participant’s verbal consent was obtained. Interviews were approximately 20 min in length and were conducted remotely via teleconference (e.g., Microsoft Teams). The two researchers (MS, LL) introduced themselves as research assistants affiliated with a university; both researchers took field notes through the conduction of all interviews. Data collection continued until no further participants expressed interest. Interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim using a transcription service (Rev.com). Demographic information was collected after the interview using an online survey (Qualtrics) with different questions for parents and children. Transcripts were reviewed for accuracy and to remove identifying information.

Data analysis

Transcripts were imported to NVivo-2 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) to conduct an inductive qualitative descriptive analysis which allowed for the effective generation of new theories based in detailed and nuanced understanding of the data [21]. Three female researchers [SJMi: White, non-immigrant, CS: South Asian, non-immigrant, HB: White, non-immigrant] with qualitative research methods familiarized themselves with the transcripts and then analyzed them independently and in triplicate. Codes were developed based on what participants described as most important and impactful when responding to questions and probes. A codebook was created for each participant group (i.e., youth or parent, separately) by identifying shared features and experiences across participants. Transcripts were coded five at a time, with the research team meeting weekly to iteratively develop the codebooks until all transcripts were coded and two finalized codebooks were generated. The finalized codebooks were then used to code all transcripts again in duplicate, and topic summaries were generated based on these codes. Responses were first analyzed by group (i.e. youth or parent, separately) and then researchers conducted a cross-analysis between the two groups to identify similarities and differences. Researchers also analyzed responses based on demographic characteristics like gender, age, and race within the youth and parental groups. Researchers aimed for rigor by carefully planning their work and consistently applying researcher reflexivity throughout the process. Following published guidance from Olmos-Vega and colleagues [22], this was achieved through reflexive writing in the form of researcher memos and field notes, as well as through engaging in structured team-reflexive discussion centered on collaboration.

Results

We interviewed 14 youth-parent dyads (28 separate interviews). Half of youth (7/14, 50%) identified as cis-gender girls, while a minority identified as cis-gender boys (6/14, 43%) or genderfluid person (1/14, 7%). The majority of youth identified as Black, Indigenous, or persons of colour (9/14, 64.3%), and nearly all youth reported that they did not identify as having a physical or intellectual disability (13/14, 93%). The median age for youth was 14 years (interquartile range (IQR) 12–16; Table 1). Most parents (8/14, 57%) identified as cis-gender women, the majority of parents identified as Black, Indigenous, or persons of colour (9/14, 64.3%), and all parents (14/14, 100%) were married; the median age was 46 years (IQR 40–50; Table 1). Parents frequently reported having obtained an undergraduate degree or greater (8/14, 57%), and most were employed full-time when the interview was conducted (9/14, 64%). More than half of the parents (8/14, 57%) lived in Canada for less than 20 years.

Table 1.

Demographics and characteristics of 15 Youth-Parent dyad interview participants

| Characteristic | Youth (11–18 years) Value, No. (%) N = 14 |

Parent (> 18 years) Value, No. (%) N = 14 |

|---|---|---|

|

Age, years 11–14 15–18 19–24 25–34 35–44 45–54 |

9 (64.2) 5 (35.7) N/A N/A N/A N/A |

N/A N/A 0 (0.0) 1 (7.14) 6 (42.9) 7 (50.0) |

|

Gender Girl/Woman/ Boy/Man Genderfluid1 |

7 (50.0) 6 (42.9) 1 (7.14) |

8 (57.1) 6 (42.9) 0 (0.0) |

|

Sex Male Female |

6 (42.9) 8 (57.1) |

8 (57.1) 6 (42.9) |

|

Disability Yes No |

1 (7.14) 13 (92.9) |

0 (0.0) 14 (100.0) |

|

Marital Status Married Single |

N/A N/A |

14 (100.0) 0 (0.0) |

|

Geographic location Atlantic (NB, NS, PEI) Central (QC, ON) Prairies (MB, SK, AB) West coast (BC) |

1 (7.14) 6 (42.9) 5 (25.7) 2 (14.3) |

1 (7.14) 6 (42.9) 5 (25.7) 2 (14.3) |

|

Number of youth (< 18) in household 0–3 >3 |

N/A N/A |

11 (78.6) 3 (21.4) |

|

Current Employment Status Parent/homemaker (full-time) Employed (full-time hours) Employed (part-time hours) |

N/A N/A N/A |

2 (14.3) 3 (21.4) 9 (64.3) |

|

Ethnicity Black, Indigenous2, or Person of Color White Prefer to self-describe |

9 (64.3) 4 (28.6) 1 (7.1) |

9 (64.3) 4 (28.6) 1 (7.1) |

|

Highest Level of Education (Completed) High School College Undergraduate (Bachelor’s) Graduate (Masters or Doctorate) |

N/A N/A N/A N/A |

1 (7.14) 4 (28.6) 7 (50.0) 2 (14.3) |

|

Canadian residence, years Less than 5 years 5 years up to 10 years 10 years up to 20 years 20 years or more |

N/A N/A N/A N/A |

1 (7.14) 3 (21.4) 4 (38.6) 6 (42.9) |

AB, Alberta; BC, British Columbia; MB, Manitoba; NB, New Brunswick; NS, Nova Scotia; ON, Ontario; PEI, Prince Edward Island; QC, Quebec; SK, Saskatchewan

1Akin to the term “gender non-binary” which is defined by Statistics Canada as including persons whose reported gender is not exclusively male or female

2Defined by Statistics Canada as a person identifies with the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This includes those who identify as First Nations (North American Indian), Métis and/or Inuk (Inuit), and/or those who report being Registered or Treaty Indians (that is, registered under the Indian Act of Canada), and/or those who have membership in a First Nation or Indian band

Youth-parent wellbeing in and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic

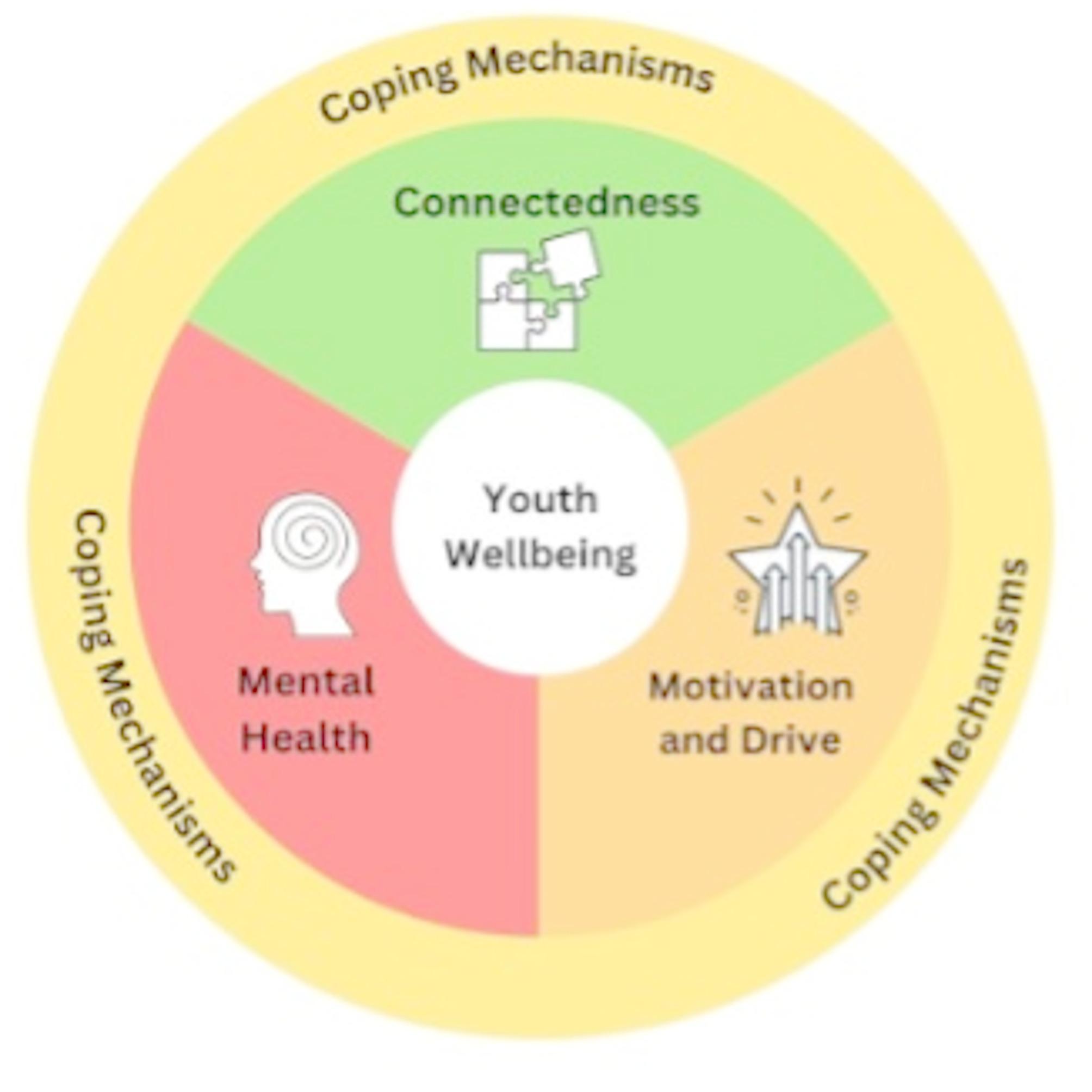

Our qualitative study examining youth and family wellbeing during, and post COVID-19 pandemic yielded four major topic summaries (Fig. 2. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Youth and Family Wellbeing). These included: (1) connectedness (a sense of being cared for, supported, and belonging), (2) motivation and drive (activating and sustaining behaviour toward a goal despite difficulties), (3) mental health (including emotional wellbeing, psychological wellbeing, social well-being and being able to navigate life complexities, develop fulfilling relationships, and adapt to change), and (4) coping mechanisms (strategies used to adjust to stressful events to help maintain overall wellbeing). Responses were consistent across demographic groups like gender, race, and age, responses remained consistent except when asked about coping mechanisms (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Youth and Family Wellbeing

Table 2.

Topic summaries and supporting quotes

| Topic summaries | Supporting quotes |

|---|---|

| Connectedness |

“When you go to school, you can hang out with friends there, socializing, you can move around. When you’re in front of a screen, you can’t move around, you’re glued to a chair” – 14-year-old boy (Dyad 12) “I would say I miss [my friends] the most out of everything and the pandemic, because I need a lot of socializing to be able to function. In the pandemic, I felt extremely alone and it [was] hard to cope with it.” – 12-year-old girl (Dyad 11) “I think the pandemic has reinforced the importance of health and the importance of family…. The last two, three years, our family has gotten stronger, not weaker.”- 50-year-old mother (Dyad 14) |

| Motivation & Drive |

“I would often find myself sleeping in until 12 or even 1:00 PM…I just didn’t have any motivation to get up early, so I was just like, why not just sleep in?” – 14-year-old girl (Dyad 8) “There was nothing [to] really care about anymore at that point. School, I never cared about because my grades couldn’t go down. I still did the homework and stuff like that, but I never put my 100% into it. And I feel like at the end of the day, it was kind of just like, this doesn’t even matter anymore…”- 17-year-old boy (Dyad 14) |

| Mental Health |

“Sometimes, because of the stress, I would be very irritated and have to stay away from people so I wouldn’t lash out at them. The stress really caused me to anger people and I was having trouble dealing with it.” – 12-year-old girl (Dyad 11) “…A lot of worries came, like, what’s graduation going to look like, what is going to university going to look like?…Just not knowing or not having an idea, because everything’s changed so much, was really worrying.” – 15-year-old girl (Dyad 3) “He had to go see a doctor because he was so depressed, [he’s] very much an extrovert…he has a huge social life. So it was difficult for him.” – 50-year-old mother (Dyad 14) |

| Coping Mechanisms |

“I will say communication, talking to each other and take care about each other’s feelings…If somebody’s quiet, we just not let that person be quiet and do things, but rather ask them if they’re okay.” – 49-year-old father (Dyad 13) “…it was really nice knowing that I had a lot of people who related to me, because all of us were just feeling the same. So, just being able to relate to people and know that I wasn’t the only one who was feeling this way was really, really helpful.” – 14-year-old girl (Dyad 8) “We said [watching the news] is not helping us. This is hurting us. It’s making us feel like we can’t even go outside because it’s doom and gloom…And yeah, we just shut it off, we turned it off. If we were discussing the pandemic, we kept it to a minimum. And that would be the conversation for the day…Does it impact us? Is it a concern, should we be worried? And then that was it. We closed it, we ended the chapter and that was it.” – 40-year-old mother (Dyad 2) |

Connectedness

The pandemic’s impact on connectedness was a significant concern for all youth and their parents. Many youth (9/14, 64%) recognized that being unable to attend school in-person was associated with reduced social interaction, physical activity, and less structured education:

“When you go to school, you can hang out with friends there, socializing, you can move around. When you’re in front of a screen, you can’t move around, you’re glued to a chair”—14-year-old boy (Dyad 12).

When asked to compare how much they missed school, friends, and extracurricular activities, youth frequently discussed missing their friends a lot (12/14, 86%). They also described how the lack of connection with friends affected their mood and ability to cope:

“I would say I miss [my friends] the most out of everything and the pandemic, because I need a lot of socializing to be able to function. In the pandemic, I felt extremely alone and it [was] hard to cope with it.”—12-year-old girl (Dyad 11).

Despite missing this connection, few youth mentioned social media when asked about coping mechanisms (3/14, 21%). Those who did described social media as more of a distraction from life in lockdown than a tool for genuine connection. One youth was even critical of his own social media usage:

“Overall, I was just scrolling social media a lot. And obviously, that can’t really help your stress at all. I guess maybe that little dopamine release you’re getting might help, but I wasn’t doing anything active. I wasn’t helping myself in any way. So I think my stress really accumulated, and so I didn’t really end up dealing with it.”—17-year-old boy (Dyad 14).

In contrast, parents perceived social media as an important tool for youth to compensate for decreased connection face-to-face. Most parents described an increase in their youth’s screen usage (13/14, 93%). While some parents described strategies to reduce screen time (4/14, 29%), others adopted more lenient approaches as they felt it was one of the few ways for youth to stay in touch with peers (3/14, 21%):

“…If they want to make those video calls and call their friends, whatever. We just let them. If that’s what’s going to help them, that’s what’s going to help them.”—39-year-old mother (Dyad 4).

Parents described planning various family activities to occupy youth and to facilitate family connectedness. Such intentional efforts had a perceived positive impact on family dynamics:

“I think the pandemic has reinforced the importance of health and the importance of family…. The last two, three years, our family has gotten stronger, not weaker.”—50-year-old mother (Dyad 14).

Motivation and drive

All youth described difficulties focusing on learning while attending school online (14/14, 100%), and most youth described a general loss of academic motivation (10/14, 71%). Some youth attributed these challenges to physical distractions such as sharing a workspace with family or having mobile phones within arm’s reach. Other youth detailed a diminished sense of control:

“There was nothing [to] really care about anymore at that point. School, I never cared about because my grades couldn’t go down. I still did the homework and stuff like that, but I never put my 100% into it. And I feel like at the end of the day, it was kind of just like, this doesn’t even matter anymore…”—17-year-old boy (Dyad 14).

In contrast, some parents remained confident in their youth’s academic performance, particularly parents of older youth where adults were less involved in online schooling:

“Well, my kids are really disciplined and they’re both very motivated…I’m past helping them for schoolwork at all and I just kept checking in for mental status more than anything and they kept their marks way up.”—51-year-old mother (Dyad 5).

Loss of motivation was frequently associated with sleep hygiene, particularly for youth with many (9/14, 64%) describing decreased sleep quality, often accompanied by extended evening hours.

“I would often find myself sleeping in until 12 or even 1:00 PM…I just didn’t have any motivation to get up early, so I was just like, why not just sleep in?”—14-year-old girl (Dyad 8).

While fewer parents discussed poor sleep quality, some parents still struggled (5/14, 36%). Youth also described decreased motivation and drive to partake in physical activity (6/14, 43%), particularly at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic where group sports and other organized physical activities were practically non-existent. Some youth described challenges in adapting from structured, group physical activity to unstructured, self-directed physical activity:

“I’ve always tried to do recreational activities and sports, and missing out on that, I think it hit my physical health as well. So I had to make up for that…And I think again, a big part of sports for me is social interaction as well.”—17-year-old boy (Dyad 14).

While many youth and parents detailed challenging moments, there was also discussion about how this experience had led personal growth. When asked whether anyone experienced an increased sense empowerment throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and in the post-pandemic period, most parents (8/14, 57%) and half of youth (7/14, 50%), discussed increased personal resiliency, dedicated time to discover activities of enjoyment, and greater self-awareness.

“I think a lot of people took the time to really focus on their self love and their self care. So I think I’m focusing on that more too and focusing on how I shouldn’t care about what other people think and just care about myself before.”—12-year-old girl (Dyad 10).

Mental health

All youth (14/14, 100%) described feeling anxious, fearful, sad, confused, or disappointed during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some youth recounted how this overwhelming mix of emotions manifested in anger:

“Sometimes, because of the stress, I would be very irritated and have to stay away from people so I wouldn’t lash out at them. The stress really caused me to anger people and I was having trouble dealing with it.”—12-year-old girl (Dyad 11).

Other youth described deep feelings of hopelessness, or powerlessness:

“Is it ever going to get better because I think we’ve had three waves now of COVID? And then we think that after the second wave, oh, things are getting better, but then just a rush of cases starts coming in, and then you think it’s hopeless.”—12-year-old girl (Dyad 10).

Youth who were older described persistent worrying and anxious feelings about how the pandemic would impact their graduation, post-secondary education plans, or the job market:

“…A lot of worries came, like, what’s graduation going to look like, what is going to university going to look like?…Just not knowing or not having an idea, because everything’s changed so much, was really worrying.”—5-year-old girl (Dyad 3).

The impact of physical restrictions and public health measures on youth mental health was one of the most frequently cited concerns among parents (7/14, 50%):

“My little ones, they understood it, but not maybe as much as my big kid. She’s the one that needs her friends and needs to talk to people, and it was a downer for her when she wasn’t just free to go see her friends kind of thing…I was one of the parents that was probably not as picky because mental health did come first for me.”—39-year-old mother (Dyad 4).

Many parents expressed sadness when describing experiences their child was missing:

“When I look back on my high school years, those were the best and most fun years of my life and I kept thinking, they’re missing this and this is where all the good stories come from and all the fun things.”—39-year-old mother (Dyad 5).

One parent described a situation where their youth developed a mental health disorder:

“He had to go see a doctor because he was so depressed, [he’s] very much an extrovert…he has a huge social life. So it was difficult for him.”—50-year-old mother (Dyad 14).

Coping mechanisms

Youth and parents described various coping mechanisms to manage reduced connections, lower motivation and drive, and poor mental health, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Coping mechanisms discussed by both youth and parents typically fell into the categories of self-management, interpersonal communication, and disconnecting from mass media.

Youth frequently cited managing stress themselves (10/14, 71%), seeking emotional support from friends or adults (9/14, 64%), playing video games (7/14, 50%), being creative (6/14, 43%), or getting outside (6/14, 43%). Youth who described managing stress themselves often stated that their problems were “silly things” (14-year-old boy, Dyad 13) that didn’t warrant confiding in someone else, or expressed the belief that they could deal with these emotions on their own. Others avoided sharing out of concern that they might “burden” family and friends who had more significant issues happening in their own lives:

“My older brother, he’s got his own stuff. He’s in university. I don’t want to have to burden him with learning about my stress, and then my friends are probably dealing with the same thing.”—17-year-old boy (Dyad 14).

Communication was the most frequently cited coping mechanism among parents (13/14, 93%), who described additional coping mechanisms that related to loosening physical distancing rules, or relaxing limitations on screen time during periods to facilitate social connection for their youth. Parents also supported their youth by encouraging healthy coping mechanisms like engaging in physical activity. When asked about the most important coping mechanisms, one parent explained:

“I will say communication, talking to each other and take care about each other’s feelings…If somebody’s quiet, we just not let that person be quiet and do things, but rather ask them if they’re okay.”—49-year-old father (Dyad 13).

Youth who confided in friends or adults detailed how sharing concerns was comforting and reduced feelings of loneliness. Youth who identified as girls were more likely to discuss connecting with friends or adults for emotional support (6/7, 86%), compared to youth who identified as boys (3/6, 50%). Communication was also a more popular coping mechanism for White youth (4/4, 100%) compared to youth who identified as POC (4/10, 40%). Youth who identified as women/girls also tended to provide clearer, more detailed explanations about why communication was a helpful coping mechanism.

“…it was really nice knowing that I had a lot of people who related to me, because all of us were just feeling the same. So, just being able to relate to people and know that I wasn’t the only one who was feeling this way was really, really helpful.”—14-year-old girl (Dyad 8).

Another coping mechanism discussed by parents was to avoid mass media (5/14, 36%). Parents described having trouble focusing during the day and feeling anxious and fearful after consuming news content.

“…whenever you opened up the news, like TV, you see everything was all about that. The COVID and COVID, like everything you hear about COVID. So it was that the distracting and getting hard to focus on the things, because it’s like all around the world. There’s only one thing that was mattered, nothing else.”—39-year-old father (Dyad 7).

One parent explained how their family recognized the negative impacts of consuming mass media early in the pandemic:

“We said [watching the news] is not helping us. This is hurting us. It’s making us feel like we can’t even go outside because it’s doom and gloom…And yeah, we just shut it off, we turned it off. If we were discussing the pandemic, we kept it to a minimum. And that would be the conversation for the day…Does it impact us? Is it a concern, should we be worried? And then that was it. We closed it, we ended the chapter and that was it.—40-year-old mother (Dyad 2).

Discussion

We conducted a semi-structured interview qualitative descriptive study to explore the perspectives of youth and their parents on knowledge, perceptions, behaviours, underlying drivers, and experiences regarding the wellbeing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings from our study provide insight into the needs of youth and parents post pandemic, enabling the development of tailored support mechanisms to counter the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic period faced by youth and families. Our findings indicated that physical distancing, school lockdowns, and other public health measures to control spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus negatively impacted youth’s feelings of connectedness, motivation and drive, and their mental health. Parents described watching their children suffer and harboured concerns regarding the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on their children’s’ development.

Connectedness and interpersonal relationships are fundamental to the socioemotional development of youth [23, 24] and these relationships were challenged throughout the COVID-19 pandemic [25, 26]. Even with close, uninterrupted friendships among peers, youth have an increased risk of mental health problems as they develop through adolescence [24]. The social distancing policies and online education mandates described by youth-parent dyads in our sample were similar to mandated policies reported by other Canadian and global child development research groups [27–29] and heavily limited activities both at school and within the wider community. As social distancing policies were applied, youth’s ability to socialize outside the classroom was restricted. Even after students returned to the classroom, policies limited participation in organized, extracurricular activities like physical recreation and competitive sports [30–32]. As public health officials focused on reducing the spread of the virus as much as possible, they broadly directed the transition to virtual education. Despite best intentions, there was very little time to consult youth and families about the potential adverse impacts of these decisions [33, 34]. The data from our interviews highlight these impacts, which should be considered in the post-COVID-19 pandemic period. Future pandemic planning needs to include diverse perspectives of youth and their parents on how to best mitigate the negative effects of social distancing policies and online education. It is critical that this planning recognize the pre-existing structural inequities that have only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic [35–37]. The majority of research has reported on viral transmission, with few including perspectives from youth themselves [38, 39]. Impacts to the family unit are vastly understudied [40], particularly experiences of parents put in the difficult situation of having to adhere to strict public health measures, including social distancing policies, or placing themselves and their youth at risk of infection from COVID-19 [41, 42] before the full primary series of COVID-19 vaccination was available [43]. At present, ongoing monitoring of youth wellbeing is essential to determining what interventions may, or may not, be required. This study highlights that while youth and families show remarkable resilience, there is still a need for services to ease these challenges. In these cases, long-term support plans provided by educational institutions and delivered through dedicated support systems such as social work teams or child psychologists would ensure that all students have the resources needed to feel their best [44]. Ultimately, policies that are underpinned by respect, humanization, and empathy, can ameliorate the impact of future public health crises on youth and their parents [45, 46].

Prior to mandated online education policies, studies reported that in-person connectedness within a school environment was critical for youth wellbeing and improved life satisfaction, self-esteem, mastery, and coping [47]. School connectedness is also strongly correlated with concurrent mental health challenges, predicting depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and general functioning, even after controlling for prior symptoms or disorders [48, 49]. Our data contributes to the literature on youth education and transitions to online delivery, highlighting implications for the assessment and creation of policies and programs aimed at supporting youth and families in the post-pandemic period [50–52]. Multi-pronged interventions to improve online school connectedness could work by informing and preparing educators with the tools, skills, and strategies to nurture online school connectedness while addressing other individual risk factors for mental health challenges. Strategies that focus on supporting youth with limited internet access are also critical to reducing pre-existing educational inequality which only worsened over the course of the pandemic [53, 54]. There is a large body of literature that evaluates factors that promote school connectedness [55–58]. Common themes in this literature that emerge as applicable and relevant to online school delivery include involving students in classroom decisions, rewarding effort rather than achievement, and avoiding any form of discrimination that includes ableism.

Limitations

The most significant strength of this study was the semi-structured interview guide which was informed by narratives on the COVID-19 pandemic [59–61] and co-designed and tested with child development experts, youth and parent public partners. One limitation to consider when interpreting the findings of our study was the number of participants which was dependent on the interest of youth-parent dyads being contacted to participate in additional research projects when completing the phase one survey [18]. Youth interviews were also conducted separately from parent interviews, doubling the time required to participate, which may have limited interest and recruitment. However, separating parents and youth allowed participants space and time to offer important insights and share perspectives which was an important strength of this study. We did not assess multiple parents (if present) or youth siblings (when applicable) and it is possible that important perspectives were missed [62]. Second, we conducted interviews over two years after the official declaration of the pandemic as we were cautious about grief experiences of youth and parents who lost loved ones to COVID-19, and recollections may have been impacted by the passage of time [63, 64]. Third, this is a single qualitative study from one country that may not be transferable to other countries and settings. Third, we recognize that the lack of cultural diversity among the researchers who conducted the interviews may have impacted the richness of the data. Finally, our sampling frame did not allow us to exhaustively explore all relevant and potentially important demographic and sociocultural factors (i.e. language, family structure) and future studies would benefit from analyzing how socioeconomic factors shaped the experiences of youth and families during the pandemic. All parental participants in our study self-reported as married, indicating that our findings do not reflect the magnitude of negative impacts on single-parent households [65, 66]. Further, we were unable to develop a deeper understanding of linguistic, technical, and cognitive barriers, that negatively impacted communication and connectedness among youth and their parents [67, 68].

Conclusion

Canadian youth and their parents in our sample perceived that public health measures enacted to control COVID-19 had unanticipated consequences, both positive and negative. Physical distancing policies and virtual education required youth to process an evolving crisis while continuing to engage in their curriculum without in-person connections to their social networks and peers. Parents of youth also struggled to stay abreast of changing guidelines and restrictions while coping with their own concerns regarding their youth’s socioemotional development. Long-term support plans for youth and their parents provided by educational institutions and delivered through dedicated support systems such as social work teams or mental health providers may help to ameliorate the impact of future public health crises. Further research with larger and more diverse sample sizes is required to validate our findings from this hypothesis-generating work to benefit pandemic planning and public health crisis preparedness.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Laura Leppan, a research assistant who played a key role interviewing participants for this study.

Abbreviations

- AB

Alberta

- BC

British Columbia

- COREQ

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research

- COVID-19

Coronavirus-19

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MB

Manitoba

- NB

New Brunswick

- NS

Nova Scotia

- ON

Ontario

- PEI

Prince Edward Island

- QC

Quebec

- SK

Saskatchewan

Author contributions

All those designated as authors (JPL, SJMo, SJMi, CS, HB, MS, DMH, SAH, SBA, DLL, SS, MH, PRT, KAB, MCA, HTS, NR, KMF) have met all ICMJE criteria for authorship.1.Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND2.Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND3.Final approval of the version to be published; AND4.Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.Conceptualization: JPL, SJMo, HTS, KMFData collection: SJMo, MSFormal analysis: SJMo, SJMi, CS, HB, MSResources: JPLSoftware: JPLSupervision: HTS, KMF, NR, JPLWriting – original draft: JPL, SJMo, SJMi, CS, HB Writing – review and editing: ALLJPL, SJMo, and SJMi made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work and drafted the work, approved the submitted version, and agreed both to be personally accountable for each author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriate investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Funding

Dr. Parsons Leigh obtained funding for this work from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) (#177722). Dr. Moss was supported by a CIHR Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Data availability

Additional summary tables of count data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID#23–0039) and Dalhousie University Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID#: #2023–6538) and was conducted in accordance with institutional privacy and protocols.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Government of Canada. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Guidance documents [2021-04-07:[Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents.html

- 2.Viner RM, Bonell C, Drake L, Jourdan D, Davies N, Baltag V, et al. Reopening schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: governments must balance the uncertainty and risks of reopening schools against the clear harms associated with prolonged closure. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(2):111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Viner RM, Russell SJ, Croker H, Packer J, Ward J, Stansfield C, et al. School closure and management practices during coronavirus outbreaks including COVID-19: a rapid systematic review. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. 2020;4(5):397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orben A, Tomova L, Blakemore S-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(8):634–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonell C, Fletcher A, Jamal F, Aveyard P, Markham W. Where next with theory and research on how the school environment influences young people’s substance use? Health Place. 2016;40:91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: considerations for policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2018;6:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas PA, Liu H, Umberson D. Family relationships and well-being. Innov Aging. 2017;1(3): igx025–igx. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(SupplSuppl):S54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ungar M. Resilience across cultures. Br J Soc Work. 2008;38(2):218–35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rek SV, Reinhard MA, Bühner M, Freeman D, Adorjan K, Falkai P, et al. Identifying potential mechanisms between childhood trauma and the psychological response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: a longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1): 12964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Ramos Rodriguez G, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North america: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nurius PS, Green S, Logan-Greene P, Borja S. Life course pathways of adverse childhood experiences toward adult psychological well-being: a stress process analysis. Child Abuse Negl. 2015;45:143–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Rodriguez GR, Sethi D, Passmore J. Life course health consequences and associated annual costs of adverse childhood experiences across Europe and North america: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(10):e517–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gómez G, Basagoitia A, Burrone MS, Rivas M, Solís-Soto MT, Dy Juanco S et al. Child-Focused mental health interventions for disasters recovery: A rapid review of experiences to inform Return-to-School strategies after COVID-19. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:713407. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.713407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Benton TD, Boyd RC, Njoroge WFM. Addressing the global crisis of child and adolescent mental health. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1108–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bell IH, Nicholas J, Broomhall A, Bailey E, Bendall S, Boland A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on youth mental health: a mixed methods survey. Psychiatry Res. 2023;321: 115082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leigh JP, Moss SJ, Sriskandarajah C, McArthur E, Ahmed SB, Birnie K, et al. A muti-informant National survey on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health symptoms of parent–child dyads in Canada. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moss SJ, Mizen SJ, Stelfox M, Mather RB, FitzGerald EA, Tutelman P, et al. Interventions to improve well-being among children and youth aged 6–17 years during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2023;21(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moss SJ, Lorenzetti DL, FitzGerald EA, Smith S, Harley M, Tutelman PR, et al. Strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and youth well-being: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open. 2022;12(7):e062413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braun V, Clarke V, Thematic. analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. APA handbooks in psychology®. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 57–71.

- 22.Olmos-Vega FM, E SR, Lara V, Kahlke R. A practical guide to reflexivity in qualitative research: AMEE guide 149. Med Teach. 2023;45(3):241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karcher MJ. The effects of developmental mentoring and high school mentors’ attendance on their younger mentees’ self-esteem, social skills, and connectedness. Psychol Sch. 2005;42(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster CE, Horwitz A, Thomas A, Opperman K, Gipson P, Burnside A, et al. Connectedness to family, school, peers, and community in socially vulnerable adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2017;81:321–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, Peskin MF, Flores B, Low B, et al. Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):S23–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitlock J. The role of adults, public space, and power in adolescent community connectedness. J Community Psychol. 2007;35(4):499–518. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A, Faizah F, Mazumder H, Zou L, et al. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res. 2020;9:636. 10.12688/f1000research.24457.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu JJ, Bao Y, Huang X, Shi J, Lu L. Mental health considerations for children quarantined because of COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(5):347–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, Moreno C, Parellada M, Arango C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: systematic review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(7):1151–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaturvedi K, Vishwakarma DK, Singh N. COVID-19 and its impact on education, social life and mental health of students: a survey. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2021;121: 105866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Branje S, Morris AS. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescent emotional, social, and academic adjustment. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31(3):486–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Munasinghe S, Sperandei S, Freebairn L, Conroy E, Jani H, Marjanovic S, et al. The impact of physical distancing policies during the COVID-19 pandemic on health and well-being among Australian adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(5):653–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al. Effects of COVID-19 home confinement on eating behaviour and physical activity: results of the ECLB-COVID19 international online survey. Nutrients. 2020;12(6):1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oosterhoff B, Palmer CA, Wilson J, Shook N. Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: associations with mental and social health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gajaria A, Guzder J, Rasasingham R. What’s race got to do with it? A proposed framework to address racism’s impacts on child and adolescent mental health in Canada. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30(2):131–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Navarro SA, Hernandez SL. The color of COVID-19: the Racial inequality of marginalized communities. Routledge; 2022.

- 37.Kemei J, Tulli M, Olanlesi-Aliu A, Tunde-Byass M, Salami B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on black communities in Canada. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(2): 1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Branquinho C, Kelly C, Arevalo LC, Santos A, Gaspar de Matos M. Hey, we also have something to say: A qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people’s experiences under COVID-19. J Community Psychol. 2020;48(8):2740–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKinlay AR, May T, Dawes J, Fancourt D, Burton A. You’re just there, alone in your room with your thoughts’: a qualitative study about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among young people living in the UK. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2): e053676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson B, Schmidt E, Mallar C, Mahmoud F, Rothenberg W, Hernandez J, et al. Risk and resilience of well-being in caregivers of young children in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl Behav Med. 2021. 10.1093/tbm/ibaa124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostermeier E, Tucker P, Tobin D, Clark A, Gilliland J. Parents’ perceptions of their children’s physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohler-Kuo M, Dzemaili S, Foster S, Werlen L, Walitza S. Stress and mental health among children/adolescents, their parents, and young adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(9): 4668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mathieu E, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M, Hasell J, Appel C, et al. A global database of COVID-19 vaccinations. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5(7):947–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickerson AB, Sulkowski ML. The COVID-19 pandemic as a long-term school crisis: impact, risk, resilience, and crisis management. School Psychol. 2021;36(5):271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dooley DG, Rhodes H, Bandealy A. Pandemic recovery for children—beyond reopening schools. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(4):347-8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hussong AM, Benner AD, Erdem G, Lansford JE, Makila LM, Petrie RC. Adolescence amid a pandemic: short-and long‐term implications. J Res Adolesc. 2021;31(3):820–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose T, McDonald A, Von Mach T, Witherspoon DP, Lambert S. Patterns of social connectedness and psychosocial wellbeing among African American and Caribbean black adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2019;48(11):2271–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma X. Sense of belonging to school: can schools make a difference?? J Educ Res. 2003;96(6):340–9. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shochet IM, Dadds MR, Ham D, Montague R. School connectedness is an underemphasized parameter in adolescent mental health: results of a community prediction study. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(2):170–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hertz MF, Kilmer G, Verlenden J, Liddon N, Rasberry CN, Barrios LC, et al. Adolescent mental health, connectedness, and mode of school instruction during COVID-19. J Adolesc Health. 2022;70(1):57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perkins KN, Carey K, Lincoln E, Shih A, Donalds R, Kessel Schneider S, et al. School connectedness still matters: the association of school connectedness and mental health during remote learning due to COVID-19. J Prim Prev. 2021;42:641–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waters SK, Cross DS, Runions K. Social and ecological structures supporting adolescent connectedness to school: a theoretical model. J Sch Health. 2009;79(11):516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golden AR, Srisarajivakul EN, Hasselle AJ, Pfund RA, Knox J. What was a gap is now a chasm: remote schooling, the digital divide, and educational inequities resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023;52: 101632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Korkmaz Ö, Erer E, Erer D. Internet access and its role on educational inequality during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telecomm Policy. 2022;46(5): 102353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monahan KC, Oesterle S, Hawkins JD. Predictors and consequences of school connectedness: the case for prevention. Prev Researcher. 2010;17(3):3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trinh L, Wong B, Faulkner GE. The independent and interactive associations of screen time and physical activity on mental health, school connectedness and academic achievement among a population-based sample of youth. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;24(1):17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lester L, Waters S, Cross D. The relationship between school connectedness and mental health during the transition to secondary school: a path analysis. Aust J Guid Couns. 2013;23(2):157–71. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Millings A, Buck R, Montgomery A, Spears M, Stallard P. School connectedness, peer attachment, and self-esteem as predictors of adolescent depression. J Adolesc. 2012;35(4):1061–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cielo F, Ulberg R, Di Giacomo D. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on mental health outcomes among youth: a rapid narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(11): 6067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salmon K. The ecology of youth psychological wellbeing in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Appl Res Mem Cogn. 2021;10(4):564–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: a narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ettekal AV, Agans JP. Positive youth development through leisure: confronting the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Dev. 2020;15(2):1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mortazavi SS, Assari S, Alimohamadi A, Rafiee M, Shati M. Fear, loss, social isolation, and incomplete grief due to COVID-19: a recipe for a psychiatric pandemic. Basic Clin Neurosci. 2020;11(2):225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Masten AS, Motti-Stefanidi F. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: reflections in the context of COVID-19. Advers Resil Sci. 2020;1(2):95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hertz R, Mattes J, Shook A. When paid work invades the family: single mothers in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Fam Issues. 2020;42(9):2019–45. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anne CG, Kimberly CT, Chris GR, Monique G, Corey M, Saima H, et al. Examining the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on family mental health in canada: findings from a National cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e042871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Serlachius A, Badawy SM, Thabrew H. Psychosocial challenges and opportunities for youth with chronic health conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Pediatr Parent. 2020;3(2): e23057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abbott A, Askelson N, Scherer AM, Afifi RA. Critical reflections on COVID-19 communication efforts targeting adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(2):159–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional summary tables of count data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.