Abstract

The susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to disinfectants was compared to that of Escherichia coli. H. pylori is more resistant than E. coli to chlorine and ozone but not monochloramine. H. pylori may be able to tolerate disinfectants in distribution systems and, therefore, may be transmitted by a waterborne route.

Helicobacter pylori colonizes 30 to 50% of the world's population. While colonization with the organism is asymptomatic in most individuals, infection with H. pylori is now recognized as a causative agent in chronic gastritis, as well as peptic and duodenal ulcer disease (1, 4, 13). In addition, infection with this organism is associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and adenocarcinoma (21, 33). Despite the medical importance of H. pylori and its widespread occurrence, little is known about the natural history of the organism.

The mode of transmission of H. pylori remains an unresolved and controversial issue. Epidemiological data support either direct person-to-person transmission or transmission through a common source, such as food or water (3, 6, 11, 17, 25, 34). Several investigations have provided evidence that H. pylori may be transmitted by contaminated drinking water (5, 7, 14-16, 19, 24, 26, 30, 31, 32). Recently, the USEPA Office of Ground Water and Drinking Water included H. pylori in its contaminant candidate list (7a), reflecting concerns over possible waterborne transmission. The potential presence of H. pylori in water necessitates the study of the efficacy of treatment processes against H. pylori in drinking water supplies.

Oxidizing disinfectants (chlorine, chloramines, and ozone) are the final barrier in the Environmental Protection Agency-recommended multibarrier approach to providing pathogen-free water to the consumer. They are the most commonly used disinfectants for drinking water (23). Hypochlorite (chlorine) has been used as a disinfectant for more than 100 years. Hypochlorites are lethal to most microbes (28). Monochloramine (NH2Cl), produced by the reaction of free chlorine and ammonia in a process called chloramination, is generally considered a leading candidate as an alternative to free chlorine. The Denver Water Department has been using chloramination as a primary water disinfection process for more than 70 years (23). While it is not as common as chlorine or monochloramine, the use of ozone is increasing in the United States. The advantages of ozone use in drinking water include a greater oxidation potential than other disinfectants and rapid decomposition of residual ozone (22).

Johnson et al. (18) examined the effect of hypochlorous acid (chlorine) on H. pylori. They concluded that there was no significant difference between the susceptibilities of H. pylori and Escherichia coli to chlorine. However, they noted that carryover of organic matter from the blood agar plates on which the H. pylori was grown may have exerted a chlorine demand in their system. We have expanded the studies of Johnson et al. by examining the effect of three different oxidizing disinfectants—chlorine, monochloramine, and ozone—on water-exposed cultures of H. pylori. In addition, we have compared the sensitivity of H. pylori to that of E. coli, the traditional indicator of microbiological water quality.

H. pylori (type strain ATCC 43504) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.). Stock cultures were maintained on 5% horse blood agar slants (BD Biosciences, Franklin, N.J.) overlaid with tryptic soy broth (BD Biosciences) supplemented with 0.25% yeast extract. The cultures were incubated under microaerophilic conditions with an AnaeroPack system, Pack-Campylo (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, New York, N.Y.) at 37°C.

An E. coli isolate was obtained from a surface water sample by spread plating onto violet red bile agar with methylumbelliferyl-β-glucuronide (BD Biosciences). Stock cultures of the organism were maintained by aerobic growth on tryptic soy broth or microaerophilic growth in biphasic culture as was done with the H. pylori culture.

Broth from mid-log-phase cultures of E. coli and H. pylori was harvested by centrifugation. Care was taken to exclude the extracellular debris that was regularly observed in the biphasic cultures. The harvested cells were resuspended in synthetic moderately hard groundwater (12) buffered with 0.05 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) (BMHW). Resuspended cells were then brought to a total volume of 10 ml and incubated at 15°C for 2 h. The resulting cell suspensions were considered to be water-exposed cells. In the case of H. pylori, microscopic examination of these suspensions indicated that most of the cells were present as individual cells and that the spiral form of the organism predominated (>80% of the cells).

Chlorine and monochloramine studies followed established protocols for the evaluation of disinfectants (2, 12, 18). All glassware was cleaned to remove chlorine demand. After cleaning, individual milk dilution bottles were filled with 100 ml of BMHW prepared in chlorine-demand-free (CDF) water. Chlorine and monochloramine stock solutions were prepared before each experiment. Chlorine stocks were made by adding 200 μl of sodium hypochlorite (Hach, Loveland, Colo.) to 100 ml of CDF water. Free and total chlorine concentrations in the stock solution were determined by the N,N-dimethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DPD) method (12). Fresh monochloramine stock was prepared by adjusting the pH of 20 ml of CDF water to 7.5 with 1 M NaOH. Ammonium phosphate [(NH3)2PO4; 320 mg] was dissolved in the water, and 100 μl of 50,000-ppm sodium hypochlorite reagent was added. The volume was immediately adjusted to 100 ml with CDF water and equilibrated for 1 h at room temperature. Combined chlorine (NH2Cl) was measured by the DPD/KI method (12). Free chlorine was below detectable levels in the monochloramine stocks.

Water-exposed cells (104 to 105 CFU/ml) were added to the bottles. Experimental bottles received chlorine or monochloramine, while control bottles received additional BMHW. A minimum of three doses (0.1, 0.2, and 0.3 mg/liter) of chlorine were evaluated in triplicate for each organism. After addition of the disinfectant, the bottles were shaken vigorously for 30 s and then incubated under static conditions for the remainder of the contact time. Initial and endpoint free and total chlorine concentrations were measured by the DPD colorimetric method. A single dose of monochloramine (1.0 mg/liter) was tested for four exposure times (1, 5, 10, and 20 min). Initial and endpoint monochloramine concentrations were measured by the DPD/KI colorimetric method.

Ozonation studies were conducted as follows. Glass bottles with Teflon-lined caps were triple rinsed with double-distilled, deionized water and autoclaved for 20 min. The bottles were then filled with O3-H2O at a concentration of 7 to 9 mg/liter as determined by the indigo colorimetric method (12) and left overnight. The bottles were drained and then baked in an 85°C oven for 1 h to ensure destruction of residual ozone.

Water-exposed cells were added to BMHW in the prepared glass bottles. The volume of BMHW in each bottle was such that the total volume would be 100 ml following the addition of O3-H2O. Ozonated water was generated with a corona discharge unit (model CD-06; Aqua-Flo Inc., Baltimore, Md.) to create O3 gas that was then bubbled into double-distilled, deionized water through an air stone. The ozonated water was then transferred to the reaction vessels containing the organisms using a glass pipette that had been soaked in O3-H2O (7 mg/liter) overnight. Control vessels contained BMHW instead of O3-H2O. The amount of ozone added to each reaction vessel was determined by taking the mean ozone concentration from duplicate indigo colorimetric measurements performed both before and after dosing with O3-H2O.

At the end of the contact time, subsamples were removed from the bottles for all of the disinfectants and immediately quenched with Na2S2O3. Viable-cell numbers were determined by spread plating onto appropriate media (E. coli, mEndo agar and aerobic incubation; H. pylori, 5% horse blood agar and microaerophilic conditions).

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data from each individual experiment were used to calculate the CT99 (CT value for 99% [2-log] reduction in viable organisms, where C is residual disinfectant concentration and T is the corresponding disinfectant contact time) for each disinfectant by plotting the log of the viable cells recovered against the mean disinfectant concentration (initial + final/2) for each experiment and determining the best-fit line by using least-squares regression. The regression lines were subsequently compared by analysis of variance. Statistical calculations were performed with Prism version 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.)

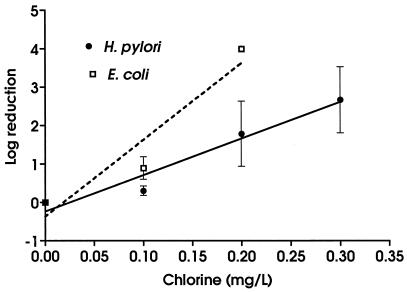

H. pylori was significantly more resistant to chlorine than E. coli (Fig. 1) (F = 12.74; P = 0.002). The difference between the two organisms was more pronounced at higher doses of chlorine. Thus, while exposure to 0.1 mg of chlorine per liter for 1 min resulted in a 0.3-log reduction in viable H. pylori cells and a 0.9-log reduction in viable E. coli cells, exposure to 0.20 mg of chlorine per liter for 1 min was associated with a 1.8-log reduction in viable H. pylori cells and a >4.0-log reduction in viable E. coli cells. The mean CT99s were 0.299 mg/liter · min for H. pylori and 0.119 mg/liter · min for E. coli. Comparison of the CT99s by using an unpaired t test indicated that they were significantly different (t = 3.26; P = 0.0471).

FIG. 1.

Effect of chlorine on H. pylori and E. coli. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Values are means ± standard deviations. Best-fit lines were calculated by using linear regression.

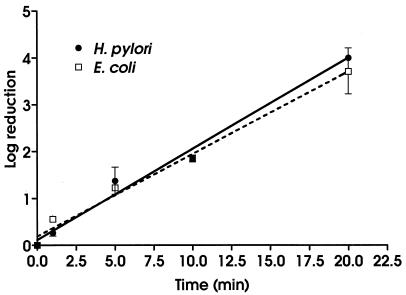

There were no significant differences between H. pylori and E. coli in susceptibility to monochloramine (Fig. 2) (F = 2.276; P = 0.148). The calculated CT99s were 9.5 mg/liter · min for H. pylori and 11 mg/liter · min for E. coli. These are not significantly different (t = 1.3; P = 0.2729)

FIG. 2.

Effect of chloramine on H. pylori and E. coli. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Values are means ± standard deviations. Best-fit lines were calculated by using linear regression.

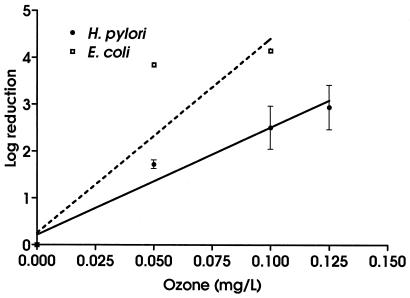

The ozonation experiments showed a pattern of susceptibility similar to that observed in the chlorination studies. H. pylori was significantly more resistant to ozonation than E. coli (Fig. 3) (F = 12.01; P = 0.003). As with chlorination, the differences between the organisms increased with increasing dose. Calculated average CT99 values for the organisms were significantly different (t = 14.00, P = 0.0051), with H. pylori having a higher CT99 (0.24 mg/liter · min) than E. coli (0.09 mg/liter · min).

FIG. 3.

Effect of ozone on H. pylori and E. coli. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Values are means ± standard deviations. Best-fit lines were calculated by using linear regression.

Our results indicate that H. pylori is significantly more resistant to the oxidizing disinfectants chlorine and ozone than E. coli. In a similar study, Johnson et al. (18) found differences between the CT99s for E. coli and H. pylori treated with chlorine. They ascribed these differences not to differences between the organisms but rather to the presence of large amounts of particulate matter and aggregated cells in the H. pylori culture. In our studies, extensive washing and water exposure of the microorganisms resulted in experimental cultures which were virtually free of particulate matter and aggregated cells. Therefore, our results support the conclusion that H. pylori is more resistant to chlorine and ozone than E. coli.

The concentrations of oxidizing disinfectants examined in this research were relatively low. A 1992 survey of disinfection practices in the United States conducted by the American Water Works Association indicated that a mean chlorine residual of 1.1 mg/liter and a median contact time of 45 min to the point of first use in the distribution system is typical for drinking water systems in the United States (10). Median levels of residual ozone used in disinfection of drinking water are reported to be 0.4 mg/liter. This is achieved by applying an ozone dose of 1.5 to 4.0 mg/liter of water (27). Therefore, it is unlikely that H. pylori enters drinking water distribution systems directly from treatment plants. Despite this, it is still possible that H. pylori may be present in municipal drinking water. Our data indicate that if H. pylori gains entry into the distribution system, via either a break in treatment or infiltration into the system itself, it may be able to survive within the distribution system, where the level of oxidizing disinfectant is reduced.

Ozone rapidly degrades to oxygen and water in treated drinking water and is generally considered to provide no lasting disinfectant residual (10). The maintenance of a chlorine residual throughout the distribution system is important for minimizing bacterial growth and for indicating (by the absence of a residual) potential water quality problems in the distribution system. Currently, maximum chlorine dosage is limited by taste and odor constraints and by the need to comply with the total trihalomethane standard. Additionally, for systems using chlorination, the surface water treatment rule requires a minimum residual of 0.2 mg/liter prior to the point of entry into the distribution system and the presence of a detectable residual throughout the system. (20). Geldreich (10) reported a free chlorine concentration of 0.1 to 0.3 as typical of distribution systems. This concentration is well within the range in which H. pylori is more resistant to free chlorine than E. coli. Therefore, H. pylori might persist in a drinking water distribution system even in the absence of E. coli.

Disinfection CT99s are based on laboratory studies using dispersed suspensions of organisms. In environmental waters, pathogens are usually aggregated or associated with cell debris, some of which may not be removed entirely by treatment processes. Cell-associated aggregates are considerably more resistant to disinfection. Once microbes are entrapped in the particles or adsorbed to surfaces, they can be shielded from disinfection (9). Biofilm bacteria grown on several surfaces were found to be 150 to 3,000 times more resistant to hypochlorous acid (free chlorine, pH 7.0) than similarly treated unattached microbes. In contrast, biofilm bacteria were 2- to 100-fold more resistant to monochloramine disinfection than unattached cells (8). Monochloramine appears to be better able to penetrate and kill biofilm bacteria than free chlorine, an important premise for maintenance of a chlorine residual.

Several researchers have examined the possible role of biofilms in the proposed waterborne transmission of H. pylori and have demonstrated that H. pylori is capable of forming biofilms under high-nutrient conditions (29) and of persisting in mixed-species drinking water biofilms (31). Recently, Park et al. (26) documented the presence of H. pylori DNA in biofilm material from an existing cast-iron mains distribution pipe. Thus, H. pylori cells that enter a distribution system may be able to survive within a biofilm matrix. Cells derived from such a biofilm may be able to survive exposure to the disinfectant levels typical of distribution systems.

Our results indicate that H. pylori is more resistant than E. coli to chlorine and ozone at concentrations normally found within distribution systems. Thus, H. pylori cells entering a distribution system from outside sources or derived from biofilms within the system may be able to persist undetected in systems using either of these disinfectants. In contrast, H. pylori is as sensitive as E. coli to disinfection with monochloramine.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the United States Geological Survey (1434-HQ-96-GR-02694).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bernstein, C. N., I. McKeown, J. M. Embil, J. F. Blanchard, M. Dawood, A. Kabani, E. Kliewer, G. Smart, G. Coghlan, S. MacDonald, C. Cook, and P. Orr. 1999. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori, incidence of gastric cancer, and peptic ulcer-associated hospitalizations in a Canadian Indian population. Dig. Dis. Sci. 44:668-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaser, M. J., P. F. Smith, W. L. Wang, and J. C. Hoff. 1986. Inactivation of Campylobacter jejuni by chlorine and monochloramine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 51:307-311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, L. M. 2000. Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission. Epidemiol. Rev. 22:283-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaun, H. 2001. Update on the role of H pylori infection in gastrointestinal disorders. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 15:251-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Enroth, H., and L. Engstrand. 1995. Immunomagnetic separation and PCR for detection of Helicobacter pylori in water and stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2162-2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Everhart, J. E. 2000. Recent developments in the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterol. Clin. N. Am. 29:559-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan, X. G., A. Chua, T. G. Li, and Q. Zeng. 1998. Survival of Helicobacter pylori in milk and tap water. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13:1096-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7a.Federal Register. 1997. Announcement of draft drinking water contaminant candidate list. Fed. Regist. 62:52193-52219.

- 8.Ford, T. E. 1993. The microbial ecology of water distribution and outfall systems, p 455-482. In T. E. Ford (ed.), Aquatic microbiology: an ecological approach. Blackwell Scientific Publishers, London, United Kingdom.

- 9.Gauthier, V., S. Redercher, and J. C. Block. 1999. Chlorine inactivation of Sphingomonas cells attached to goethite particles in drinking water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:355-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geldreich, E. E. 1996. Microbial quality of water supply in distribution systems. Lewis Publishers, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 11.Goodman, K. J., P. Correa, H. J. Aux Tengana, H. Ramirez, J. P. DeLany, G. Guerrero Pepinosa, M. Lopez Quinones, and T. Collazos Parra. 1996. Helicobacter pylori infection in the Colombian Andes: a population-based study in transmission pathways. Am. J. Epidemiol. 144:290-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg, A. E., L. S. Clesceri, and A. D. Eaton (ed.). 1992. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 18th ed. American Public Health Association,Washington, D.C.

- 13.Hassall, E. 2001. Peptic ulcer disease and current approaches to Helicobacter pylori. J. Pediatr. 138:462-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hegarty, J. P., M. T. Dowd, and K. H. Baker. 1999. Occurrence of Helicobacter pylori in surface water in the United States. J. Appl. Microbiol. 87:697-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hulten, K., H. Enroth, T. Nystrom, and L. Engstrand. 1998. Presence of Helicobacter species DNA in Swedish water. J. Appl. Microbiol. 85:282-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hulten, K., S. W. Han, H. Enroth, P. D. Klein, A. R. Opekun, R. H. Gilman, D. G. Evans, L. Engstrand, D. Y. Graham, and F. A. El-Zaatari. 1996. Helicobacter pylori in the drinking water in Peru. Gastroenterology 110:1031-1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jimenez-Guerra, F., P. Shetty, and A. Kurpad. 2000. Prevalence of and risk factors for Helicobacter pylori infection in school children in Mexico. Ann. Epidemiol. 10:474-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson, C. H., E. W. Rice, and D. J. Reasoner. 1997. Inactivation of Helicobacter pylori by chlorination. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4969-4970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein, P. D., D. Y. Graham, A. Gaillour, A. R. Opekun, and E. O. Smith. 1991. Water source as risk factor for Helicobacter pylori infection in Peruvian children. Gastrointestinal Physiology Working Group. Lancet 337:1503-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koivusalo, M., and T. Vartiainen. 1997. Drinking water chlorination by-products and cancer. Rev. Environ. Health 12:81-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Konturek, P. C., S. J. Konturek, T. Starzyska, K. Marlicz, W. Bielanski, P. Pierzchalski, E. Karczewska, A. Hartwich, K. Rembiasz, M. Lawniczak, W. Ziemniak, and E. C. Hahn. 2000. Helicobacter pylori-gastrin link in MALT lymphoma. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 14:1311-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langlas, B., D. A. Reckhow, and D. R. Brink (ed.). 1991. Ozone in water treatment: application and engineering. American Water Works Association Research Foundation and Compagnie Général des Eaux cooperative research report. Lewis Publishers, Chelsea, Mich.

- 23.Margolin, A. B. 1997. Control of microorganisms in source water and drinking water, p. 195-202. In C. J. Hurst, G. R. Knudsen, M. J. McInerney, L. D. Stetzenbach, and M. V. Walter (ed.). Manual of environmental microbiology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 24.McKeown, I., P. Orr, S. Macdonald, A. Kabani, R. Brown, G. Coghlan, M. Dawood, J. Embil, M. Sargent, G. Smart, and C. N. Bernstein. 1999. Helicobacter pylori in the Canadian arctic: seroprevalence and detection in community water samples. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 94:1823-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendall, M. A., P. M. Goggin, N. Molineaux, J. Levy, T. Toosy, D. Strachan, and T. C. Northfield. 1992. Childhood living conditions and Helicobacter pylori seropositivity in adult life. Lancet 339:896-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park, S. R., W. G. Mackay, and D. C. Read. 2000. Helicobacter sp. recovered from drinking water biofilm sampled from a water distribution system. Water Res. 35:1624-1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peeters, J. E., E. A. Mazas, W. J. Masschelein, I. V. Martinez de Maturana, and E. Debacker. 1989. Effect of disinfection of drinking water with ozone or chlorine dioxide on survival of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1519-1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rutala, W. A., and D. J. Weber. 1997. Uses of inorganic hypochlorite (bleach) in health-care facilities. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:597-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasaki, K., Y. Tajiri, M. Sata, Y. Fujii, F. Matsubara, M. Zhao, S. Shimizu, A. Toyonaga, and K. Tanikawa. 1999. Helicobacter pylori in the natural environment. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 31:275-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shahamat, M., U. Mai, C. Paszko-Kolva, M. Kessel, and R. R. Colwell. 1993. Use of autoradiography to assess viability of Helicobacter pylori in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59:1231-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stark, R. M., G. J. Gerwig, R. S. Pitman, L. F. Potts, N. A. Williams, J. Greenman, I. P. Weinzweig, T. R. Hirst, and M. R. Millar. 1999. Biofilm formation from Helicobacter pylori. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Velazquez, M., and J. M. Feirtag. 1999. Helicobacter pylori: characteristics, pathogenicity, detection methods and mode of transmission implicating foods and water. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 53:95-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang, X., R. Willen, C. Andersson, and T. Wadstrom. 2000. Development of high-grade lymphoma in Helicobacter pylori-infected C57BL/6 mice APMIS 108:503-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamashita, Y., T. Fujisawa, A. Kimura, and H. Kato. 2001. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a serologic study of the Kyushu region in Japan. Pediatr. Int. 43:4-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]