Abstract

An efficient insertion mutagenesis strategy for bacterial genomes based on the phage Mu DNA transposition reaction was developed. Incubation of MuA transposase protein with artificial mini-Mu transposon DNA in the absence of divalent cations in vitro resulted in stable but inactive Mu DNA transposition complexes, or transpososomes. Following delivery into bacterial cells by electroporation, the complexes were activated for DNA transposition chemistry after encountering divalent metal ions within the cells. Mini-Mu transposons were integrated into bacterial chromosomes with efficiencies ranging from 104 to 106 CFU/μg of input transposon DNA in the four species tested, i.e., Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Erwinia carotovora, and Yersinia enterocolitica. Efficiency of integration was influenced mostly by the competence status of a given strain or batch of bacteria. An accurate 5-bp target site duplication flanking the transposon, a hallmark of Mu transposition, was generated upon mini-Mu integration into the genome, indicating that a genuine DNA transposition reaction was reproduced within the cells of the bacteria studied. This insertion mutagenesis strategy for microbial genomes may be applicable to a variety of organisms provided that a means to introduce DNA into their cells is available.

Transposons are mobile DNA elements that mediate genome rearrangements by inserting themselves within and between genomes. These elements are the main cause of numerous biological phenomena, including the emergence of insertion mutations that often lead to inactivation of gene function, the spread of antibiotic resistance genes among bacterial populations, and the integration of retroviruses into their host genome (5, 11, 33). Recent findings also suggest that the immunoglobulin gene rearrangement machinery may be derived from an ancestral transposon system (1, 22).

Transposons are indispensable tools in modern genetics. The original in vivo transposition-based strategies (for reviews, see references 4 and 25) paved the way for further in vitro transposition-based developments that utilize the mechanisms of a variety of transposable elements, including Tn10, Ty1, Tn5, Tn552, Mu, Tn7, and mariner (6, 9, 13, 14, 17, 19, 41). Typical transposon applications include gene mapping and DNA sequencing strategies as well as insertion mutagenesis and functional genetic analysis methods (for recent microbial examples, see references 2, 10, 18, 20, 34, 36, and 38). DNA transposition-based strategies have also been employed successfully in functional analyses of proteins (21) and studies on protein-DNA complexes (43).

Bacteriophage Mu replicates its genome using DNA transposition machinery and is one of the best-characterized mobile genetic elements (8, 29). Its transposition reaction consists of DNA cleavage and joining steps and occurs within higher-order protein-DNA complexes called transpososomes (12, 39). While Mu transposition, both in vivo and with plasmid substrates in vitro, is complex and requires a variety of protein and DNA cofactors (8, 29), a substantially simplified version of the reaction can be reproduced in vitro by altering reaction conditions and critical DNA substrates (12, 19, 32).

In the simplest case, Mu transposition complexes can be assembled in vitro using MuA transposase protein and a transposon right-end (R-end) segment that includes two MuA binding sites. These complexes contain four molecules of MuA that synapse two molecules of the end segment (32). Analogously, when two R-end sequences are located as terminal inverted repeats in a longer DNA molecule, transposition complexes form by synapsing the transposon ends (12, 19) (Fig. 1A). The complexes remain inactive in the absence of metal ions but are activated for transposition chemistry upon addition of Mg2+. The majority of complexes subsequently execute two-ended transposon integration involving both transposon ends and generate a transposition DNA intermediate containing 5-nucleotide single-stranded regions flanking the transposon DNA. Within compatible cells (e.g., Escherichia coli), the intermediate can be repaired by host machinery, resulting in a 5-bp target site duplication that is a hallmark of Mu transposition (3, 12, 19, 24, 29).

FIG.1.

(A) Relationship between mini-Mu transposon integration into plasmid DNA in vitro (19) and in vivo chromosomal DNA integration by in vitro-assembled Mu transposition complexes (this study). In both cases, a tetramer of MuA transposase (gray circles) and mini-Mu transposon ends assemble into a stable protein-DNA complex, designated Mu transposition complex or Mu transpososome. Upon encountering Mg2+ ions (in vitro or in vivo), the complex executes two-ended integration (involving both transposon ends) of transposon DNA into target DNA. The ensuing transposition DNA intermediate contains 5-nucleotide single-stranded regions flanking the integrated transposon DNA that are ultimately repaired by host machinery in vivo 12, 19; this study). Linear mini-Mu transposons in this study are defined as segments of DNA that contain 50 bp of Mu R-end DNA as inverted repeats at each end (19, 32). In the precut form, the transposon 3" ends (black dots) are exposed and readily available for the transposon integration reaction, also known as the strand transfer reaction (12, 19, 32). (B) DNA substrates used in this study. For the sake of clarity the features depicted are not to scale. The rectangles in the transposon DNA ends indicate 50 bp of Mu R-end DNA. Kan and Cat, neomycin phosphotransferase and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase genes, respectively. Small arrows, binding sites of the primers used for DNA sequencing. Bg and B, restriction sites of BglII and BamHI, respectively.

To date, Mu in vitro transposition-based strategies have been utilized for a variety of molecular biology applications, including DNA sequencing (20), functional analysis of plasmid DNA and virus genome regions (19, 27), analysis of proteins by pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis (40), and generation of DNA constructs for gene targeting (42). To extend the scope of Mu technology, we examined whether preformed Mu transposition complexes can be utilized as delivery vehicles for gene integration into bacterial genomes. Here, we report the assembly of integration-proficient Mu transposition complexes that, after introduction into bacterial cells by electroporation, execute transposon integration into bacterial chromosomes with high efficiency and fidelity, generating an accurate 5-bp target site duplication. This strategy may be applicable to a variety of organisms in which efficient genetic manipulation systems are lacking or difficult to exploit.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Proteins, DNA techniques, DNA, and reagents.

Restriction endonucleases and Vent DNA polymerase were from New England Biolabs. MuA transposase was from Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland. Plasmids and chromosomal DNAs of bacterial species were isolated with the Plasmid Minikit (Qiagen) and the Genomic Isolation Kit with 100/G tips (Qiagen), respectively. Standard DNA techniques were performed as described previously (30), and enzymes were used according to suppliers' recommendations. DNA sequencing was performed using the Global Edition IR2 System (LI-COR Inc., Lincoln, Nebr.). Mini-Mu transposons (Fig. 1B), Cat-Mu (19) and Kan-Mu (identical to Entransposon-Kanr [Finnzymes]), were isolated either directly by BglII digestion from their respective pUC19-derived carrier plasmids (see reference 19 and plasmid pEntransposon-Kanr [Finnzymes]) or indirectly from appropriate PCR products generated using Vent DNA polymerase and pUC19-specific forward (pUC Fwd, 5"-AGCTGGCGAAAGGGGGATGTG) and reverse (pUC Rev, TTATGCTTCCGGCTCGTATGTTGTGT) primers. BglII digestion generates precut transposon ends and leaves 4-nucleotide 5" overhangs flanking the transposon. Such an end configuration in mini-Mu transposons ensures efficient assembly of stable transpososomes (19, 32). The control fragment (Cat) (Fig. 1B) was generated from Cat-Mu by BamHI digestion, eliminating the transposon ends. DNA fragments were purified using anion-exchange chromatography as described previously (20). Plasmid pUC19 was from New England Biolabs. Control plasmid pBR322-Cm was generated from pBR322 (New England Biolabs) by Cat-Mu in vitro transposition. Kan-Mu sequencing primers were SeqA (5"-ATCAGCGGCCGCGATCC) and SeqB (5"-TTATTCGGTCGAAAAGGATCC). Cat-Mu sequencing primers were Muc1 (5"-GCTCTCCCCGTGGAGGTAAT) and SeqB. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) and heparin were from Sigma, [α-32P]dCTP (1,000 to 3,000 Ci/mmol) was from Amersham, Ficoll 400 was from Pharmacia, and agarose (NuSieve 3:1) was from BioWhittaker Molecular Applications.

Bacterial strains.

E. coli laboratory strains (cultured at 37°C) were MC1061 (28), DH10B (16), HB101 (7), and BL21 (37). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 strain SL5676 (26) (cultured at 28°C), Erwinia carotovora strain LMG2404 (ATCC 15713) (cultured at 28°C), and Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3 strain 6471/76-c (35) (cultured at 25°C) were obtained from A. M. Grahn (University of Helsinki), H. Saarilahti (University of Helsinki), and M. Skurnik (University of Turku), respectively.

Electrocompetent cells.

Electrocompetent cells were prepared similarly for all four bacterial species. An overnight culture grown in SOB medium (20 g of tryptone per liter, 5.0 g of yeast extract per liter, 0.584 g of NaCl per liter, and 0.186 g of KCl per liter, adjusted to pH 7.0 with NaOH) was diluted (1:1,000) in a total volume of 500 ml of SOB and grown to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm in a Sorvall GSA rotor at 4°C for 10 min. For washing, the cell pellet was resuspended in 500 ml of ice-cold 10% (vol/vol) glycerol and recentrifuged as described above for 15 min. The washing step was repeated. The pellet was subsequently resuspended in 10% glycerol (total volume, 2 ml). Cells were frozen as aliquots in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until thawed for electroporation.

Transpososome assembly and electroporation.

The standard in vitro transpososome assembly reaction mixture (20 μl) contained 1.1 pmol of transposon DNA, 4.9 pmol of MuA, 150 mM of Tris-HCl (pH 6.0), 50% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.025% (wt/vol) Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA. The reaction was carried out at 30°C for 2 h. To detect stable protein-DNA complexes, samples were electrophoresed (with buffer circulation) in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (30) for 2 h at 5.3 V/cm at 4°C on a native 2% agarose gel containing 87 μg of BSA per ml and 87 μg of heparin per ml. In this case, 0.2 volume of 25% Ficoll 400 was added to the samples for gel loading. However, to dissociate noncovalent protein-DNA complexes (see Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 6), samples were loaded on the gel by addition of 0.2 volume of Ficoll-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution (25% Ficoll 400, 2.5% SDS). The ethidium bromide-stained gel was photographed on Polaroid 665 film, and quantification from negatives was done using a Fluor-S MultiImager (Bio-Rad). For electroporation, the transpososome assembly reaction mixture was diluted (1:4 or more) with water. Individual aliquots (1 μl) were electroporated into electrocompetent cells (25 μl) using a Genepulser II (Bio-Rad) at the following settings: capacitance, 25 μF; voltage, 1.8 kV; and resistance, 200 Ω (Bio-Rad 1-mm electrode spacing cuvettes). Following electroporation, 1 ml of SOC medium (30) per aliquot was added and bacteria were grown for 40 min. Subsequently, bacteria were spread onto Luria-Bertani agar plates (30) containing 10 μg of chloramphenicol per ml or 25 μg of kanamycin per ml for selection of Cat-Mu and Kan-Mu, respectively.

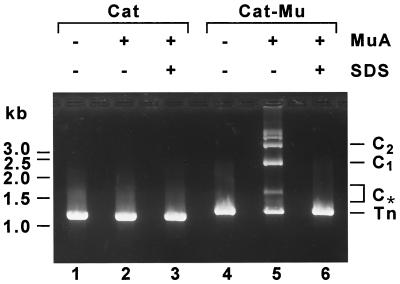

FIG. 2.

Mu transposition complex formation with Cat and Cat-Mu substrates (see Fig. 1B) analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Substrate DNA was incubated with or without MuA, and the reaction products were analyzed in the presence or absence of SDS. Samples were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (30) containing 87 μg of heparin per ml and 87 μg of BSA per ml. Under these electrophoretic conditions, essentially all detectable complexes represent transpososomes (32). C1 and C2, transposition complexes whose migration is consistent with formation between the ends of a single transposon and with formation between the ends of two transposons, respectively. Complexes that exhibit slow electrophoretic mobility represent several transposons linked together via transposition complexes. C*, series of complexes whose migration is consistent with different topological forms of C1 complexes. Tn, unreacted substrate DNA.

Determination of target site duplication.

Chromosomal DNA of each antibiotic-resistant isolate was digested with PstI, generating a fragment with a transposon attached to its chromosomal DNA flanks. These fragments were then cloned into the PstI site of pUC19. DNA sequences of transposon borders were determined from these recombinant plasmids by using transposon-specific primers reading sequences outwards from within the transposon. Genomic locations were identified by using a BLAST search at National Center for Biotechnology Information servers.

Southern blotting.

Genomic DNA, digested with PstI or NcoI, was electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel and blotted onto a Hybond membrane (Amersham). Southern hybridization (30) was carried out with α-32P-labeled (Random Primed; Roche) Cat-Mu as a probe.

RESULTS

In the absence of divalent metal ions, Mu transpososomes that assemble with precut transposon ends are stable but catalytically inert. The complexes withstand not only conventional (30) but also relatively harsh electrophoresis conditions and remain stable even when challenged with high concentrations of heparin embedded in an agarose gel (31, 32; this study). Therefore, it is conceivable that after electroporation into bacterial cells, these complexes remain functional and become activated for transposition chemistry upon encountering Mg2+ ions within the cells, potentially facilitating transposon integration into host chromosomal DNA. This hypothesis was tested experimentally.

The assembly of Mu transpososomes was initially examined by incubating the MuA protein with the Cat-Mu transposon and analyzing the formation of stable protein-DNA complexes by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 2). The reaction with Cat-Mu transposon generated several bands of protein-DNA complexes (lane 5) that disappeared when the same sample was loaded in the presence of SDS (lane 6), thus indicating that covalent protein-DNA interactions are not involved in complex formation. The migration pattern of these complexes is consistent with Mu transpososomes connecting the ends of a single or several transposon molecules (see the legend to Fig. 2). A control DNA fragment lacking Mu transposon end sequences failed to produce detectable complexes (Fig. 2, lane 2). Next, an aliquot of each assembly reaction mixture was electroporated into E. coli cells, and bacterial clones were selected for chloramphenicol resistance. Only the sample containing detectable protein-DNA complexes yielded chloramphenicol-resistant (Cmr) colonies (with a frequency of 105 CFU/μg of input transposon DNA). A similar frequency was obtained with the Kan-Mu transposon after selection for kanamycin resistance (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Number of antibiotic resistant colonies detected following electroporation into E. coli MC1061a

| Substrate DNAb | Selected resistance | No. of antibiotic-resistant colonies (CFU/μg of DNA) after:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| No preincubation with MuA | Preincubation with MuA | ||

| Cat | Chloramphenicol | 0 | 0 |

| Cat-Mu | Chloramphenicol | 0 | 1 × 105 |

| Kan-Mu | Kanamycin | 0 | 6 × 104 |

Twelve nanograms of DNA (1 μl) was used for electroporation. The competence status of these cells was 5 × 108 CFU/μg of pBR322-Cm DNA.

Substrate DNA molecules are depicted diagrammatically in Fig. 1B.

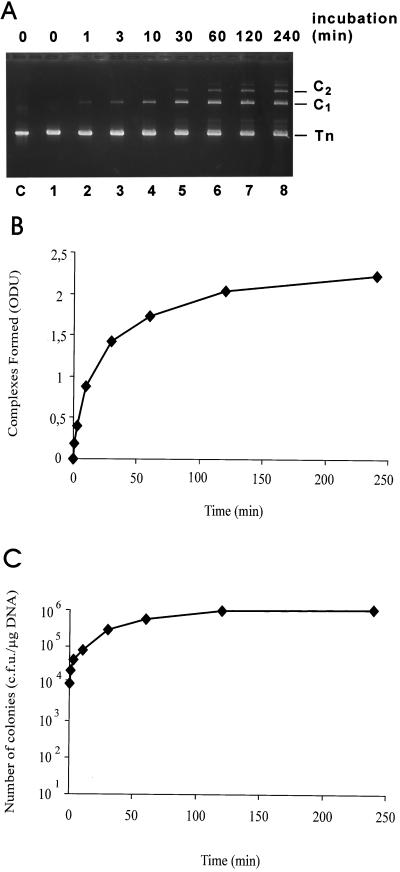

Accumulation of the complexes and their relationship to the capacity for colony formation was then examined in a time course experiment (Fig. 3). Formation of the complexes correlated with the appearance of resistant colonies. Collectively, these results suggest that the detected complexes (or a fraction of them) are responsible for the appearance of resistant colonies. Transposon integration by transpososomes in vivo is consistent with these findings.

FIG. 3.

Time course of complex and colony formation. (A) A 2% agarose gel. Analysis was performed with Cat-Mu substrate as for Fig. 2 with no SDS in the sample loading step. Lanes 1 to 8, reaction time course; lane C, Cat-Mu transposon DNA as a control. (B) Quantitation of complex formation. The C1 complexes formed were quantified (see Materials and Methods) from the ethidium bromide-stained gel shown in panel A. ODU, arbitrary optical density units. (C) Formation of chloramphenicol-resistant colonies after electroporation into E. coli strain MC1061.

Other laboratory strains of E. coli were tested for comparison with the above-described results (Table 2). The competence status of each strain was evaluated in parallel by electroporation of a control plasmid. The most efficient strain, MC1061, produced approximately 106 antibiotic-resistant colonies/μg of input transposon DNA (12 ng of DNA electroporated), while the least efficient strain, HB101, displayed an efficiency of less than 105 CFU/μg of input transposon DNA. No colonies were detected in any of the corresponding control reaction mixtures for the E. coli strains (no added MuA protein, 12 ng of transposon DNA electroporated). However, control experiments in which greater amounts of transposon DNA (500 ng) were electroporated into these E. coli strains yielded detectable colonies, although with a low frequency (≈101 CFU/μg of DNA). These colonies most likely represent spontaneous resistance-generating mutations, or possibly recombination events involving a mechanism(s) other than DNA transposition, and were not studied further.

TABLE 2.

Number of chloramphenicol-resistant colonies detected following electroporation into different bacterial strains

| Reaction | DNA electroporated (amt, ng)a | Preincubation with MuA | No. of chloramphenicol-resistant colonies (CFU/μg of DNA)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli K-12

|

E. coli (BL21) | S. enterica serovar Typhimurium L2 SL5676 | E. carotovora LMG2404 | Y. enterocolitica serotype O:3 (6471/76-C) | ||||||||

| MC10161 | DH10B | HB101 | ||||||||||

| Standard | Cat-Mu (12) | Yes | 9 × 105 | 2 × 105 | 6 × 104 | 3 × 104 | 3 × 104 | 1 × 105 | 2 × 104 | |||

| Cat-Mu (12) | No | —c | — | — | — | — | — | — | ||||

| Control | Cat-Mu (500) | No | 3 × 101 | 2 × 101 | 3 × 101 | 2 × 101 | — | — | — | |||

| pBR322-Cmb (1) | No | 2 × 109 | 3 × 108 | 3 × 108 | 4 × 108 | NDd | ND | ND | ||||

One microliter of DNA solution was electroporated. For standard reactions, the standard assembly reaction solution was diluted 1:4 with water. For control reactions, the DNA was in solution in water.

Electroporation of plasmid pBR322-Cm DNA served as a control for competence status.

—, no colonies detected.

ND, not determined.

As might be expected, the capacity for colony formation correlated with the competence status of each strain. Furthermore, different batches of electrocompetent cells of a given strain exhibited variable capacities for colony formation that correlated with their competence status (data not shown). The assembled transpososomes were stable for several months when stored at −80°C, since no reduction in colony formation capacity was detected after prolonged storage (data not shown).

We next examined whether transposon DNA was inserted into the chromosomal DNA of Cmr clones and, moreover, the number of transposon copies present. Chromosomal DNAs from 17 potential transposon integration clones were isolated, digested with PstI (which does not cut the transposon sequence), and analyzed by Southern hybridization with a Cat-Mu transposon probe. Each isolate generated a single band with a discrete gel mobility (Fig. 4A). A parallel analysis was performed using NcoI, which cleaves the transposon sequence once. Two bands of different gel mobility were generated for each isolate (Fig. 4B). Control chromosomal DNA from the strain that we initially used for electroporation did not generate bands in the analyses. These data indicate that a single copy of transposon DNA was integrated into the chromosome of each isolate.

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis of insertions into the bacterial chromosome. Genomic DNAs of 17 chloramphenicol-resistant E. coli DH10B clones were digested with PstI (A) or NcoI (B) and probed with Cat-Mu transposon DNA. Lanes: 1 to 17, transposon insertion mutants; M, molecular size marker; C, genomic DNA of original E. coli DH10B recipient strain as a negative control; P, linearized plasmid DNA containing Cat-Mu transposon sequence as a positive control.

Genuine Mu transposition produces a 5-bp target site duplication flanking the integrated transposon (3, 19, 24). To investigate whether the integration events detected were indeed caused by transposition, we determined the DNA sequences (see Materials and Methods) on both sides of the transposon in nine randomly selected E. coli clones. In each case, the integrated transposon was flanked by a target site duplication, thus confirming that integrations were generated by DNA transposition chemistry (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Transposon integration sites and target site duplications

| Strain | Clone | Sequencea | Transposon orientationb | Genetic locationc

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Coordinates | Section | ||||

| E. coli K-12 | C1 | tttcaatataTTGCT(Cat-Mu)TTGCTggagtttgag | + | mrdA | 5173-5177 | 58 |

| DH10B | C2 | ggcgacacctACGGA(Cat-Mu)ACGGAcgcgttttta | + | yhdX | 10168-10172 | 295 |

| C4 | tgacgatgccGTTGC(Cat-Mu)GTTGCggtagcaccg | + | hrpB | 2039-2043 | 14 | |

| C5 | ccaggtcataTTCAG(Cat-Mu)TTCAGgccatcatct | − | bglX | 6810-6814 | 192 | |

| C6 | gtcgctaatgCCGGA(Cat-Mu)CCGGAgacaatacca | − | ycjJ | 10126-10130 | 117 | |

| C7 | tcactccagcGCAGC(Cat-Mu)GCAGCaccatcaccg | − | lacZ | 8143-8147 | 31 | |

| C9 | caaagtatgcCCGTC(Cat-Mu)CCGTCtggccagtgc | − | fes | 10020-10024 | 53 | |

| K2 | tgtttaattgCCGGA(Kan-Mu)CCGGAtgtcagacat | + | yhjG | 1748-1752 | 319 | |

| K3 | aggtgataccCTGGC(Kan-Mu)CTGGCggcctgcctg | − | yrfI | 7397-7401 | 305 | |

| S. enterica | S5 | tcaacatcaaGCGGC(Cat-Mu)GCGGCaggaaagagg | + | Unknown | ||

| serovar | S6 | cgaca-caacAGCAA(Cat-Mu)AGCAAcctggtacag | + | Unknown | ||

| Typhimurium | S7 | gctc-t-acgCAGAC(Cat-Mu)CAGACgatgtaacgt | + | Unknown | ||

| LT2 SL5676 | S8 | gtattgcagcGCAGG(Cat-Mu)GCAGGcgctggtgaa | + | Unknown | ||

| E. carotovora | E1 | gagctccggcGTAGG(Cat-Mu)GTAGGcgagtccacc | + | Unknown | ||

| type strain | E2 | ctgcgtgctgCTGCC(Cat-Mu)CTGCCgattctgttt | + | Unknown | ||

| LMG2402 | E3 | atcgatcacgCTATC(Cat-Mu)CTATCgataaagcta | + | Unknown | ||

| E4 | attcgt-tctGTCTG(Cat-Mu)GTCTGggttcaccaa | + | Unknown | |||

| Y. enterocolitica | Y9 | cggca-tattTTGGG(Cat-Mu)TTGGGggctaaattt | + | Unknown | ||

| serotype | Y10 | aaatgagtatCCGGC(Cat-Mu)CCGGCatctgaatat | + | Unknown | ||

| O:3 (6471/76-c) | Y11 | acggatactgGCAGG(Cat-Mu)GCAGGtaaagaaatc | + | Unknown | ||

| Y12 | gcg-aattatGCCGC(Cat-Mu)GCCGCtgcatcagtg | + | Unknown | |||

Nucleotides that were difficult to interpret in the sequencing analysis are indicated by hyphens. Target site duplications are in boldface capital letters.

Compared to the genomic sequences shown, the transcription from the transposon proceeds from left to right (+) or from right to left (−).

The protocol was extended to other bacterial species (Table 2). The three additional species tested, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, E. carotovora, and Y. enterocolitica, produced Cmr colonies at efficiencies comparable to those obtained with the E. coli strains. Control reactions lacking MuA produced no colonies. Similar to the E. coli studies, each clone that was analyzed from these bacterial species contained a target site duplication flanking the transposon DNA (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

We developed a gene delivery methodology for bacterial cells that results in the integration of artificial transposons into the bacterial chromosome. The system is based on the in vitro assembly of the bacteriophage Mu DNA transposition complexes and their subsequent electroporation into bacterial cells (Fig. 1A). The strategy utilizes mini-Mu transposons that contain a pair of MuA binding sites as inverted terminal repeats at each end (Fig. 1B). Upon MuA binding, these sites promote the assembly of a tetrameric Mu transposition complex that functions as a molecular machine to splice the transposon into target DNA in a divalent metal ion (e.g., Mg2+)-dependent manner (12, 19, 32).

The precut mini-Mu transposons used in this study have exposed 3" ends and contain several extra 5"-flanking nucleotides at each end. These features facilitate the formation of stable complexes that become activated for strand transfer after encountering Mg2+ ions (31, 32). Our data indicate that this activation also takes place within bacterial cells after electroporation. We obtained up to ≈106 integrants/μg of input transposon DNA with standard E. coli strains used for high-efficiency plasmid transformation. In general, the efficiency of integration per microgram of input transposon DNA was about three orders of magnitude lower than the plasmid electroporation efficiency. The competence status of electrocompetent cells was a major variable affecting integration frequency, and consistent differences were observed both between bacterial strains and between different batches of a particular strain.

Importantly, mini-Mu transposon insertions are stable in cells that do not express MuA. However, at least in E. coli cells, it is likely that the inserted transposons can be further mobilized by expressing MuA (e.g., using plasmid expression systems).

We were able to detect only a limited number of antibiotic-resistant colonies when the transposon DNA was electroporated alone (with no added MuA) into the E. coli strains used in this study. Furthermore, similar control experiments for the other bacterial species studied produced no resistant colonies (Table 2). These results were not unexpected and are consistent with the general assumption that the bacterial species tested do not contain an efficient machinery for the recombination of incoming nonhomologous DNA.

Transposons represent the mutagenesis system of choice for genetic studies that require gene inactivation. They provide primer binding sites that can be used to retrieve DNA sequence information flanking the transposon insertion site, thereby allowing direct access to a particular gene of interest. Thus, the approach described here for the efficient mutagenesis of various bacterial genomes should facilitate molecular analyses of diverse biological processes. While it is clear that different mutants may be analyzed separately, an opportunity for the development of remarkably efficient strategies lies in the analysis of pools of insertion mutants. For example, recently developed bacterial genomic footprinting techniques (2, 44) may be directly applicable to Mu-generated mutant banks.

We have established that DNA transposition complexes assembled with artificial mini-Mu transposons can be introduced into bacterial cells, whereby transposons become integrated into the genome. Since the molecular machinery functioned well also when complexes were introduced into cells other than those of E. coli (the natural host of phage Mu), we conclude that Mu integration in these cases occurred without the aid of E. coli host proteins. This is in contrast to standard Mu DNA transposition in vivo, which involves a number of protein and DNA cofactors (8, 29). However, our results are not entirely unexpected given that the cofactors involved in standard Mu DNA transposition are required specifically for steps leading to transposition complex formation and are not essential thereafter. We have yet to define the upper limit for the length of mini-Mu transposons that can be utilized for efficient chromosomal integration. To date, the longest transposons utilized by our group in standard in vitro transposition experiments (into plasmid targets) are 6.8 kb in length. These transposons function almost as efficiently as 1- to 2-kb transposons, and thus it is probable that they function in chromosomal integration as well.

The present study describes mini-Mu transposon integration events in gram-negative bacteria. However, since the transposition machinery is fully functional on encounter with DNA and Mg2+ ions, in principle the strategy could also be applicable to gram-positive bacteria and perhaps to some eukaryotic organisms (such as yeast) as well. While host-encoded restriction systems may create an impediment to efficient functioning of the system in some organisms, this problem may be circumvented by custom designing transposons that do not contain critical recognition sites or by using mini-Mu transposons isolated from a compatible bacterial strain. Host proteases in some organisms may cause additional problems by destroying incoming transpososomes prior to chromosomal integration. However, given the success of our approach in different bacteria, it may be that transpososome function is activated immediately upon binding of divalent metal ions within the cell. Thus, the subsequent series of reactions may actually occur very rapidly, thereby preventing proteases from locating and destroying transpososomes inside cells prior to integration.

Thus far, a strategy similar to that presented here for Mu has been described only for Tn 5-derived minitransposons (15, 23). Nevertheless, since a common DNA transposition mechanism is shared among a variety of mobile elements (11), it is likely that other in vitro DNA transposition systems, such as Tn10, Ty1, Tn552, Tn7, and mariner (6, 9, 13, 17, 41), may also be utilized analogously.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mikko Frilander, Paul Gottlieb, Saija Haapa-Paananen, Pekka Lappalainen, and Martin Romantschuk for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Ari-Matti Saren and Kirsi Multanen for their help with BLAST searches and DNA sequencing, respectively.

Financial support was obtained from the Academy of Finland (to A.L. and H.S.) and the Technology Development Centre, Finland (to H.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrawal, A., Q. M. Eastman, and D. G. Schatz. 1998. Transposition mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 and its implications for the evolution of the immune system. Nature 394:744-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akerley, B. J., E. J. Rubin, A. Camilli, D. J. Lampe, H. M. Robertson, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1998. Systematic identification of essential genes by in vitro mariner mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:8927-8932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allet, B. 1979. Mu insertion duplicates a 5 base pair sequence at host inserted site. Cell 16:123-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berg, C. M., and D. E. Berg. 1995. Transposable elements as tools for molecular analysis in bacteria, p. 38-68. In D. J. Sherratt (ed.), Mobile genetic elements. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- 5.Berg, D. E., and M. M. Howe (ed.). 1989. Mobile DNA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.

- 6.Biery, M. C., F. J. Stewart, A. E. Stellwagen, E. A. Raleigh, and N. L. Craig. 2000. A simple in vitro Tn 7-based transposition system with low target site selectivity for genome and gene analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1067-1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyer, H. W., and D. Roulland-Dussoix. 1969. A complementation analysis of the restriction and modification of DNA in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 41:459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaconas, G., B. D. Lavoie, and M. A. Watson. 1996. DNA transposition: jumping gene machine, some assembly required. Curr. Biol. 6:817-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalmers, R. M., and N. Kleckner. 1994. Tn 10/IS 10 transposase purification, activation, and in vitro reaction. J. Biol. Chem. 269:8029-8035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colegio, O. R., T. J. Griffin, N. D. F. Grindley, and J. E. Galan. 2001. In vitro transposition system for efficient generation of random mutants of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 183:2384-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig, N. L. 1995. Unity in transposition reactions. Science 270:253-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craigie, R., and K. Mizuuchi. 1987. Transposition of Mu DNA: joining of Mu to target DNA can be uncoupled from cleavage at the ends of Mu. Cell 51:493-501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devine, S. E., and J. D. Boeke. 1994. Efficient integration of artificial transposons into plasmid targets in vitro: a useful tool for DNA mapping, sequencing and genetic analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:3765-3772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goryshin, I. Y., and W. S. Reznikoff. 1998. Tn 5 in vitro transposition. J. Biol. Chem. 273:7367-7374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goryshin, I. Y., J. Jendrisak, L. M. Hoffman, R. Meis, and W. S. Reznikoff. 2000. Insertional transposon mutagenesis by electroporation of released Tn 5 transposition complexes. Nat. Biotechnol. 18:97-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grant, S. G., J. Jessee, F. R. Bloom, and D. Hanahan. 1990. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:4645-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Griffin, T. J., IV, L. Parsons, A. E. Leschziner, J. DeVost, K. M. Derbyshire, and N. D. Grindley. 1999. In vitro transposition of Tn 552: a tool for DNA sequencing and mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:3859-3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwinn, M. L., A. E. Stellwagen, N. L. Craig, J. F. Tomb, and H. O. Smith. 1997. In vitro Tn 7 mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae Rd and characterization of the role of atpA in transformation. J. Bacteriol. 179:7315-7320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haapa, S., S. Taira, E. Heikkinen, and H. Savilahti. 1999. An efficient and accurate integration of mini-Mu transposons in vitro: a general methodology for functional genetic analysis and molecular biology applications. Nucleic Acids Res. 27:2777-2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haapa, S., S. Suomalainen, S. Eerikäinen, M. Airaksinen, L. Paulin, and H. Savilahti. 1999. An efficient DNA sequencing strategy based on the bacteriophage Mu in vitro DNA transposition reaction. Genome Res. 9:308-315. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes, F., and B. Hallet. 2000. Pentapeptide scanning mutagenesis: encouraging old proteins to execute unusual tricks. Trends Microbiol. 8:571-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hiom, K., M. Melek, and M. Gellert. 1998. DNA transposition by the RAG1 and RAG2 proteins: a possible source of oncogenic translocations. Cell 94:463-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman, L. M., J. J. Jendrisak, R. J. Meis, I. Y. Goryshin, and W. S. Reznikoff. 2000. Transposome insertional mutagenesis and direct sequencing of microbial genomes. Genetica 108:19-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahman, R., and D. Kamp. 1979. Nucleotide sequences of the attachment sites of bacteriophage Mu. Nature 280:247-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser, K., J. W. Sentry, and D. J. Finnegan. 1995. Eukaryotic transposable elements as tools to study gene structure and function, p. 69-100. In D. J. Sherratt (ed.), Mobile genetic elements. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- 26.Kotilainen, M. M., A. M. Grahn, J. K. Bamford, and D. H. Bamford. 1993. Binding of an Escherichia coli double-stranded DNA virus PRD1 to a receptor coded by an IncP-type plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 175:3089-3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurent, L. C., M. N. Olsen, R. A. Crowley, H. Savilahti, and P. O. Brown. 2000. Functional characterization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome by genetic footprinting. J. Virol. 74:2760-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meissner, P. S., W. P. Sisk, and M. L. Berman. 1987. Bacteriophage lambda cloning system for the construction of directional cDNA libraries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4171-4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mizuuchi, K. 1992. Transpositional recombination: mechanistic insights from studies of Mu and other elements. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 61:1011-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 31.Savilahti, H., and K. Mizuuchi. 1996. Mu transpositional recombination: donor DNA cleavage and strand transfer in trans by the Mu transposase. Cell 85:271-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savilahti, H., P. A. Rice, and K. Mizuuchi. 1995. The phage Mu transpososome core: DNA requirements for assembly and function. EMBO J. 14:4893-4903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherrat, D. J. (ed.). 1995. Mobile genetic elements. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England.

- 34.Singh, I. R., R. A. Crowley, and P. O. Brown. 1997. High-resolution functional mapping of a cloned gene by genetic footprinting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:1304-1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skurnik, M. 1984. Lack of correlation between the presence of plasmids and fimbriae in Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 56:355-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith, V., D. Botstein, and P. O. Brown. 1995. Genetic footprinting: a genomic strategy for determining a gene's function given its sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:6479-6483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Studier, F. W., A. H. Rosenberg, J. J. Dunn, and J. W. Dubendorff. 1990. Use of T7 RNA polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185:60-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun, Y. H., S. Bakshi, R. Chalmers, and C. M. Tang. 2000. Functional genomics of Neisseria meningitidis pathogenesis. Nat. Med. 6:1269-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Surette, M. G., S. J. Buch, and G. Chaconas. 1987. Transpososomes: stable protein-DNA complexes involved in the in vitro transposition of bacteriophage Mu DNA. Cell 49:253-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taira, S., J. Tuimala, E. Roine, E. L. Nurmiaho-Lassila, H. Savilahti, and M. Romantschuk. 1999. Mutational analysis of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato hrpA gene encoding Hrp pilus subunit. Mol. Microbiol. 34:737-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tosi, L. R., and S. M. Beverley. 2000. cis and trans factors affecting Mos1 mariner evolution and transposition in vitro, and its potential for functional genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:784-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vilen, H., S. Eerikäinen, J. Tornberg, M. Airaksinen, and H. Savilahti. 2001. Construction of gene-targeting vectors: a rapid Mu in vitro DNA transposition-based strategy generating null, potentially hypomorphic, and conditional alleles. Transgenic Res. 10:69-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wei, S. Q., K. Mizuuchi, and R. Craigie. 1997. A large nucleoprotein assembly at the ends of the viral DNA mediates retroviral DNA integration. EMBO J. 16:7511-7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong, S. M., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2000. Genetic footprinting with mariner-based transposition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10191-10196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]