Abstract

Background.

The clinical course and outcomes of alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) remain poorly understood. Major adverse liver outcomes (MALO) do not capture the added risk of return to drinking (RTD). We examined the natural history of AH and developed a composite endpoint using a contemporary observational cohort of AH.

Methods.

A cohort of 1127 participants: 712 AH patients, 256 heavy drinking (HD) controls without clinically evident liver disease, and 159 healthy controls, were prospectively followed for 6-months at eight United States centers as part of the Alcoholic Hepatitis Network (AlcHepNet) consortium. Outcomes included mortality and a composite endpoint (AlcHepNet composite index) that included death, liver transplantation, hepatic decompensation (new onset/worsening ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), liver-related hospital admission, MELD increase ≥5, and return to drinking (RTD).

Results.

Of 712 AH patients (age 45±10.7 years; 59.1% male), 558 (79.0%) had severe and 148 (21.0%) had moderate AH, 232 (32.5%) died, and 86 (12.1%) underwent liver transplantation. Mortality rates in moderate AH and severe AH were 0.7% vs.17.2% (30d), 3.4% vs. 26.5% (90d), and 8.8% vs. 30.5% (180d), respectively (all p<0.001). Composite liver/alcohol use events were noted in 459 (64.5%) AH patients. Higher MELD score, lower mean arterial pressure, and baseline leukocytosis were associated with higher 90-day mortality in AH (all p<0.05). College education and higher alkaline phosphatase were associated with lower mortality. HD controls had low mortality (n=3;1.2%).

Discussion.

This large observational study showed a high incidence of composite liver and alcohol-use events within six months, reiterating the need for early interventions.

Keywords: Alcohol- associated hepatitis, prospective, multicenter, composite event, outcomes

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence, healthcare consequences, and economic impact of acute alcohol-associated hepatitis (AH) continue to increase in the United States 1–5. Currently, AH is the leading cause of liver disease-related hospitalization and emergency room visits and accounts for nearly 20% of in-hospital mortality5. Notably, the definition of AH used in multiple clinical studies also includes patients with underlying cirrhosis 6–9. Recent clinical trials have reported conflicting results regarding the impact of pharmacotherapy in severe AH 10–13. The Steroids Or Pentoxifylline in Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) trial, conducted in Europe, reported 14%, 30%, and 57% mortality at 28 days, 90 days, and one year, respectively, in patients treated with steroids 14. Similarly, the Defeat Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (DASH) trial conducted in the United States found mortality rates of 18%, 42%, and 44% at 28, 90, and 180 days, respectively, in patients with severe AH receiving corticosteroid therapy 12. In contrast, a recent trial conducted by the Alcoholic Hepatitis Network (AlcHepNet) showed corticosteroid therapy coupled with a stopping rule of 7-day Lille score <0.4515 resulted in much lower mortality of 3%, 10%, and 19% at 30, 90, and 180 days, respectively 13, suggesting that the use of the Lille score significantly lowers mortality of AH in corticosteroid-treated patients.

Recent epidemiological studies have reported that younger patients and those from racial and ethnic minority groups now account for an increasing proportion of AH cases 6,16. Sepsis and multiorgan failure have long been recognized as the leading causes of death in AH 6,10,12,13,17. Thus, implementing hospital infection control protocols could significantly reduce the risk of adverse clinical outcomes 18,19. The absence of placebo controls in recent clinical trials also limits our understanding of the natural progression of AH. Notably, two recently completed multicenter randomized trials in AH did not include a placebo arm 12 13. Observational studies generate data that supplement the findings of clinical trials. The Translational Research and Evolving Alcoholic Hepatitis Treatment (TREAT) study, which included 164 patients with AH and 131 concurrently enrolled heavy-drinking controls without liver injury, reported a one-year mortality of 25% in AH20. However, the modest sample size limited a more comprehensive assessment of the clinical outcomes in patients with AH. Composite outcomes/MALO that include important clinical events such as mortality and morbidity (decompensation, hospitalization, and return to drinking) may help determine healthcare utilization and resource allocation but have not been evaluated in patients with AH. We aimed to identify critical outcomes and generate a composite outcome measure highly relevant to clinical practice.

We present data from a prospective observational study that includes patients with both moderate and severe AH compared to heavy drinking (HD) and healthy controls (HC). We aimed to generate a composite outcome measure that includes critical outcomes highly relevant to clinical practice in patients with AH. Major adverse liver outcomes (MALO) that include liver-related deaths, liver transplant, new onset development of ascites and hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal bleeding, have been suggested as relevant to clinical outcomes in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)21. Clinically relevant events in AH also include liver-related hospital admission for worsening ascites, HE, infection, or GI bleeding, an increase in MELD ≥ 5, and return to drinking within 6 months, as well as MALO. Here we present a novel composite clinical endpoint (AlcHepNet Composite Index) that offers a comprehensive, clinically relevant analysis of patients with AH for use in designing future trials.

METHODS

Study Design

This prospective observational study was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) and conducted by the AlcHepNet consortium concurrently with their published clinical trial 22 13. The study design and diagnosis criteria have been reported in previous publications 22,23. A more detailed description of the cohort is provided in the Supplementary Methods and Results section.

Demographic data (age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, highest educational level), vital signs, anthropometry, medical history, and concomitant medications; complications of portal hypertension (ascites, jaundice, varices, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatocellular carcinoma); laboratory values with calculated Maddrey’s Discriminant Function (MDF), Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio index (APRI), and Child-Pugh (CP) scores; and hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, or human immunodeficiency virus status were collected. MELD scores were used to classify AH severity. We defined moderate AH as MELD < 20 and severe AH as MELD ≥ 20 based on our prior criteria.

Participants

Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for the three groups have been reported elsewhere 23 and in Supplementary Methods and Results. The study cohort included patients referred from outside medical centers. In brief, participants were over 21 years of age and provided written informed consent in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration on Human Studies. AH Inclusion criteria: Adult patients with AH defined by NIAAA consensus criteria24 with a total bilirubin > 3 mg/dL. A liver biopsy was done in only a small minority of patients (n=71; 10%), all of whom met the criteria for Definite AH. In the remaining patients (n=641; 90%), the diagnosis of “Probable” AH was based primarily on clinical criteria. AH exclusion criteria: Etiologies of liver disease other than alcohol-associated liver disease (ALD), including hemochromatosis, autoimmune liver disease, Wilson disease, and viral hepatitis. The site investigator determined the significance of other liver diseases in causing liver damage. None of the patients participated in other clinical trials or administered “off-label” or other experimental treatments for ALD, including but not limited to anakinra or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (GCSF). Since there are no FDA-approved treatments of AH, there was wide variability in the use of corticosteroids based on clinical team preferences. Hence, corticosteroid use was initiated before they were included, and the use was documented and analyzed as obtained.

HD inclusion criteria:

History of chronic heavy alcohol consumption, or that sufficient to cause liver damage, i.e., >40 g/day or >280g/week on average for women and >60 g/day or >420 g/week on average for men but without documented liver disease. HD Exclusion criteria: Individuals with past evidence of ALD, defined as a bilirubin > 2.0 mg/dL, an AST > 1.5 ULN, any hospital admission for liver disease, or the presence of esophageal varices or ascites (at any time in the past) were excluded. AH patients were recruited when in the hospital, HD patients were recruited from alcohol-rehabilitation programs, and HC patients by advertisement in public locations.

Alcohol consumption.

Timeline Follow-Back was administered systematically at baseline and each follow-up visit. The full AUDIT was administered at baseline. PEth was not collected systematically due to the costs and the perceived need at the time of enrollment, as PEth levels measured on stored blood were not considered reliable. Abstinence was defined as a binary outcome (Yes/No) based on a combined but independent assessment by the clinical team.

Outcomes

The protocol-based follow-up was for 180 days, but we included earlier time points to show that mortality occurred early in this cohort. Early censoring markers show loss to follow-up, withdrawal from the study, or liver transplantation. Patient data were reviewed every 24 weeks to capture mortality, and the details of these analyses were reported earlier13. A review of the available clinical data was used to identify the most likely cause of death. All-cause mortality is reported since liver-related mortality had not been prespecified or adjudicated, and almost all deaths that occur within the 6 months in AH are liver-related. A composite of liver disease and alcohol use events: all-cause mortality, and MALO after recruitment (liver transplantation, new onset of clinically detectable ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), liver-related hospital admission (for worsening ascites, HE, infection, or GI bleeding), increase in MELD ≥ 5, and early return to drinking within 6-months of recruitment was used to create the AlcHepNet Composite index. Although RTD (within 6 months) is not a direct liver-related outcome, we included this outcome because early RTD is a significant contributor to delayed liver-related mortality25. By including RTD and MALO with other clinically relevant liver-related events, we have direct measures of liver outcomes within 6 months and a composite index that will likely predict additional liver outcomes beyond the 6 months of our study.

We also determined the proportion of patients who recompensated during follow-up. Although the study was prospective, the time of resolution and timing of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and variceal hemorrhage from diagnoses were not part of the protocol. We therefore defined a reduction in MELD score (≤5 points from enrollment) as a surrogate for recompensation/improvement in liver function. Rates of specific types of events were calculated and reported, specifically the cumulative incidence rate of liver transplantation per patient report and 90- and 180-day mortality. Combinations of individual components of composite events are shown as UpSet plots that allow for integration of multiple shared or unique outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as percentages. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance. Details of statistical approaches are described in Supplementary Methods and Results.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of AH and HD

The study cohort included 712 subjects with AH, 256 with HD, and 159 who were HC (Fig 1). The demographics are shown in Table 1, Table S1. As expected, participants with AH had significantly higher bilirubin (total and direct), serum creatinine, AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, total WBC, MCV, INR, PT, and lower albumin, total protein, hemoglobin, platelet count, eGFR and mean arterial pressure (MAP) compared to HD subjects (p values <0.001) (Table 1; Table S1). Before enrollment, 168 patients were started on steroids, but only 57 continued on steroids during the study (Table S2). An additional 23 patients started steroids after enrollment. Of the 80 patients who received steroids during the study period, sufficient data were available to evaluate the Day 7 Lille score in 69 (Table S3). Most of our cohort had severe AH (79.0%), characterized by high MELD (21.0% MELD <20 vs. 31.6% MELD 20–25, 19.4% MELD 26–30, and 28.0% MELD >30), Child-Pugh (10.3±1.8), and Maddrey’s Discriminant Function scores (55.1±35.8) (Table 1; Table S1; Fig S1). Although mean APRI scores (3.3±3.4) may suggest that most participants with AH had advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis (Fig S1D), the elevated value may be influenced by AST and thrombocytopenia in AH.

Fig. 1.

Participant enrollment in AlcHepNet observational study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all AlcHepNet OBS study participants

| Overall n=1109 | Subjects with AH n=709 | Heavy drinkers without AH n=246 | Healthy control n=154 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days of follow-up (median with IQR) | 135.0 (19.0, 229.0) | 135.0 (30.0, 219.0) | 219.0 (151.0, 252.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | <.001 |

| Age at OBS enrollment | 44.7 ± 12.3 | 45.0 ± 10.7 | 48.8 ± 13.4 | 36.6 ± 13.4 | <.001 |

| Gender assigned at birth | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 491 (44.4%) | 289 (40.9%) | 105 (42.7%) | 97 (63.0%) | |

| Male | 616 (55.6%) | 418 (59.1%) | 141 (57.3%) | 57 (37.0%) | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||

| Non-white | 212 (19.6%) | 97 (14.0%) | 69 (28.3%) | 46 (31.7%) | |

| White | 868 (80.4%) | 594 (86.0%) | 175 (71.7%) | 99 (68.3%) | |

| BMI (mean) | 28.9 ± 7.3 | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 28.3 ± 7.2 | 26.5 ± 5.6 | <.001 |

| BMI (median) | 27.5 (23.8, 32.5) | 28.2 (24.4, 33.4) | 26.5 (23.6, 31.2) | 25.2 (22.7, 29.8) | <.001 |

| BMI Category | <.001 | ||||

| Normal weight BMI<25 | 327 (32.4%) | 180 (27.9%) | 81 (36.3%) | 66 (47.5%) | |

| Overweight 25<=BMI<30 | 322 (31.9%) | 200 (31.0%) | 80 (35.9%) | 42 (30.2%) | |

| Obese BMI>=30 | 359 (35.6%) | 266 (41.2%) | 62 (27.8%) | 31 (22.3%) | |

| Waist circumference (at the umbilicus) | 101.7 ± 18.1 | 107.8 ± 16.8 | 99.4 ± 16.8 | 89.0 ± 15.5 | <.001 |

| Waist circumference (at largest diameter) | 103.8 ± 18.0 | 109.3 ± 17.6 | 102.1 ± 16.1 | 92.0 ± 15.1 | <.001 |

| Hip circumference | 104.3 ± 15.6 | 105.0 ± 16.9 | 106.1 ± 14.6 | 100.4 ± 13.0 | 0.005 |

| Mid-upper arm circumference (between shoulder and elbow) | 28.3 ± 5.7 | 27.4 ± 5.7 | 30.1 ± 5.7 | 29.2 ± 5.1 | <.001 |

| Waist-Hip Ratio | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | <.001 |

| Education status | <.001 | ||||

| No college education | 359 (34.3%) | 269 (41.2%) | 83 (34.3%) | 7 (4.6%) | |

| College education | 689 (65.7%) | 384 (58.8%) | 159 (65.7%) | 146 (95.4%) | |

| Marital status | 0.044 | ||||

| Not married | 681 (62.9%) | 412 (60.1%) | 166 (68.0%) | 103 (67.3%) | |

| Married | 401 (37.1%) | 273 (39.9%) | 78 (32.0%) | 50 (32.7%) | |

| Study completion status | <.001 | ||||

| Did not complete | 519 (55.0%) | 409 (71.1%) | 110 (50.9%) | ||

| Completed | 425 (45.0%) | 166 (28.9%) | 106 (49.1%) | 153 (100.0%) | |

| Main reason for early discontinuation | <.001 | ||||

| No longer meets inclusion/exclusion criteria | 6 (1.2%) | 1 (0.2%) | 5 (4.5%) | ||

| Death | 176 (33.9%) | 173 (42.3%) | 3 (2.7%) | ||

| Liver Transplant | 80 (15.4%) | 80 (19.6%) | |||

| Other reason(s) | 30 (5.8%) | 19 (4.6%) | 11 (10.0%) | ||

| Patient lost to follow-up | 192 (37.0%) | 110 (26.9%) | 82 (74.5%) | ||

| Patient withdrew consent | 35 (6.7%) | 26 (6.4%) | 9 (8.2%) | ||

| Hospitalized due to alcoholic hepatitis within 1 year prior to baseline visit | <.001 | ||||

| No | 832 (76.3%) | 436 (62.9%) | 244 (99.6%) | 152 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 258 (23.7%) | 257 (37.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| Age of first drink (mean ± SD) | 18.3 ± 6.1 | 18.6 ± 5.9 | 17.3 ± 7.3 | 18.9 ± 3.9 | 0.007 |

| Alcohol use at baseline | <.001 | ||||

| No | 207 (20.5%) | 123 (19.8%) | 7 (2.9%) | 77 (52.4%) | |

| Yes | 802 (79.5%) | 497 (80.2%) | 235 (97.1%) | 70 (47.6%) | |

| Steroid use | <.001 | ||||

| Never | 928 (83.7%) | 533 (75.2%) | 241 (98.0%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| At least once | 181 (16.3%) | 176 (24.8%) | 5 (2.0%) | ||

| Liver biopsy data available | 0.004 | ||||

| No/Not done | 1090 (98.3%) | 690 (97.3%) | 246 (100.0%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 19 (1.7%) | 19 (2.7%) | |||

| History of cirrhosis | <.001 | ||||

| No | 1058 (95.4%) | 658 (92.8%) | 246 (100.0%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 51 (4.6%) | 51 (7.2%) | |||

| History of liver transplant | <.001 | ||||

| No | 1029 (92.8%) | 629 (88.7%) | 246 (100.0%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 80 (7.2%) | 80 (11.3%) | |||

| MELD Score (mean ± SD) | 19.8 ± 11.5 | 26.4 ± 8.3 | 6.9 ± 1.8 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | <.001 |

| Meld Score Classification | <.001 | ||||

| MELD score < 20 | 502 (47.7%) | 148 (21.2%) | 219 (100.0%) | 135 (100.0%) | |

| MELD score 20–25 | 220 (20.9%) | 220 (31.5%) | |||

| MELD score 26–30 | 135 (12.8%) | 135 (19.3%) | |||

| MELD score >30 | 195 (18.5%) | 195 (27.9%) | |||

| Child-Pugh Score | 8.5 ± 2.8 | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 5.2 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.1 | <.001 |

| Maddrey’s Discriminant Function | 33.1 ± 41.2 | 54.9 ± 35.7 | −7.1 ± 6.0 | −5.4 ± 4.8 | <.001 |

| APRI | 2.3 ± 3.1 | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 0.4 ± 1.1 | 0.3 ± 0.8 | <.001 |

| Estimated GFR (MDRD) | 79.5 ± 34.7 | 74.0 ± 39.7 | 88.0 ± 20.8 | 91.5 ± 19.1 | <.001 |

| Albumin | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.4 | <.001 |

| Total Bilirubin | 11.4 ± 12.4 | 17.4 ± 11.7 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | <.001 |

| Direct Bilirubin | 7.5 ± 8.9 | 12.1 ± 8.6 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 1.2 | <.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | <.001 |

| ALT | 40.9 ± 41.5 | 48.7 ± 34.4 | 31.9 ± 62.0 | 19.3 ± 9.7 | <.001 |

| AST | 92.9 ± 81.1 | 127.8 ± 73.6 | 35.6 ± 62.9 | 20.4 ± 5.9 | <.001 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 142.0 ± 105.9 | 181.8 ± 112.0 | 75.5 ± 32.9 | 61.8 ± 18.3 | <.001 |

| Total Protein | 6.3 ± 1.0 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.8 ± 2.7 | 9.4 ± 1.8 | 13.3 ± 2.0 | 13.8 ± 1.6 | <.001 |

| Total WBC (x 10^9 /L) | 10.5 ± 7.5 | 12.8 ± 8.4 | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | <.001 |

| Platelet Count (10^9 /L) | 178.8 ± 98.9 | 136.9 ± 83.4 | 255.5 ± 88.9 | 249.4 ± 59.7 | <.001 |

| MCV | 96.9 ± 9.5 | 100.7 ± 8.8 | 91.7 ± 7.1 | 87.7 ± 5.2 | <.001 |

| INR | 1.6 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | <.001 |

| PT | 18.1 ± 7.2 | 21.6 ± 6.7 | 11.4 ± 1.4 | 11.9 ± 1.5 | <.001 |

| MAP | 86.4 ± 12.8 | 83.0 ± 11.5 | 95.3 ± 13.2 | 88.2 ± 10.9 | <.001 |

| Status at 30 Days | <.001 | ||||

| Alive | 1018 (91.8%) | 618 (87.2%) | 246 (100.0%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Dead | 91 (8.2%) | 91 (12.8%) | |||

| Status at 90 Days | <.001 | ||||

| Alive | 963 (86.8%) | 566 (79.8%) | 243 (98.8%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Dead | 146 (13.2%) | 143 (20.2%) | 3 (1.2%) | ||

| Status at 180 Days | <.001 | ||||

| Alive | 939 (84.7%) | 542 (76.4%) | 243 (98.8%) | 154 (100.0%) | |

| Dead | 170 (15.3%) | 167 (23.6%) | 3 (1.2%) |

Note: Values expressed as n(%), mean±SD, or median (Q1,Q3). Abbreviations: AH: Alcoholic hepatitis; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; APRI: Aspartate Aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; INR: International Normalized Ratio; IQR: Interquartile Range; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OBS: Observational; PT: Prothrombin Time; SD: Standard Deviation; WBC: White Blood Cell Count

Mortality and liver disease severity in individuals with AH

The median length of the follow-up was 154 days (interquartile range or IQR: 34.5 – 232.5 days). Two hundred and thirty-two (33%) of the 712 patients with AH died during follow-up. Among these, 97 (13.6%) died within 30 days, 153 (21.5%) died within 90 days, and 183 (25.7%) died within 180 days. The total number of deaths in participants with AH was 232, which included those who died after 180 days and those who died after loss-to-follow-up. We used Kaplan-Meier curves to depict the mortality-time distributions of patient groups stratified by MELD score. Mortality risk was higher with higher MELD scores at both 30 and 90 days (Fig. 2). The unstratified overall survival and transplant-free survival of patients with AH at 90 days were 76.4% and 67.0%, respectively. (Fig. S2 A,B).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall survival in patients with AH, stratified by baseline MELD scores.

We further compared the characteristics of those patients with AH who died and those who did not die within 90 days (Table S4). Patients with AH who died were more likely to have a higher BMI (31.3 ± 7.7 vs. 29.1 ± 7.5; p=0.002), larger waist circumference (115.6 ± 20.6 cm vs. 108.4 ± 16.9 cm; p=0.012), and elevated MELD score (32 ± 8.0 vs. 25 ± 7.8; p<0.001). They also had higher Child-Pugh scores (11.0 ± 1.7 vs. 10.1 ± 1.8; p<0.001), MDF scores (76 ± 39.1 vs. 49 ± 32.5; p<0.001), total bilirubin (24.6 ± 12.1 mg/dL vs. 15.5 ± 10.9 mg/dL; p<0.001), serum creatinine (2.2 ± 2.1 mg/dL vs. 1.3 ± 1.5 mg/dL; p<0.001), total WBC count (15.5 ± 10.4 × 109/L vs. 12.0 ± 7.5 ×109/L; p<0.001), INR (2.3 ± 0.7 vs. 1.9 ± 0.6; p<0.001), and PT (24.7 ± 7.7 s vs. 20.7 ± 6.1 s; p<0.001). Compared to the patients with AH who survived, those who died had lower eGFR (52.1 ± 32.2 vs. 80.1 ± 39.6; p<0.001), total protein (5.6 ± 0.9 vs. 5.9 ± 0.9; p=0.001), hemoglobin (9.1 ± 1.9 vs. 9.4 ± 1.7; p=0.022), platelet count (117.1 ± 77.8 × 109/L vs. 142.4 ±84.5 × 109/L; p=0.001), MCV (99.4 ± 8.3 vs. 101 ± 8.9 fL; p=0.042), and MAP (78.4 ± 11.6 vs. 84.2 ± 11.2 mmHg; p<0.001).

Among the 232 patients who died, the most frequently observed cause of death in AH was liver decompensation/multiorgan failure, accounting for 47.4% of the deaths; the next most frequent specified cause of death was infection, including septic shock (7.8%), followed by renal failure (6.9%) (Table 2). Causes of death were unspecified in 73 of the 232 patients who died (31.5%). Hepatocellular carcinoma was the least frequent (0.43%) cause of death in the study cohort.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of AlcHepNet OBS subjects with AH stratified by 90-day mortality

| Overall n=709 | Alive at 90 days post-AH n=566 | Dead at 90 days post-AH n=143 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at OBS enrollment | 45.0 ± 10.7 | 44.7 ± 10.6 | 46.1 ± 11.0 | 0.172 |

| Gender assigned at Birth | 0.387 | |||

| Female | 289 (40.9%) | 226 (40.1%) | 63 (44.1%) | |

| Male | 418 (59.1%) | 338 (59.9%) | 80 (55.9%) | |

| Race | 0.205 | |||

| Non-white | 97 (14.0%) | 73 (13.2%) | 24 (17.4%) | |

| White | 594 (86.0%) | 480 (86.8%) | 114 (82.6%) | |

| BMI (mean) | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 29.2 ± 7.5 | 31.2 ± 7.8 | 0.009 |

| BMI (median) | 28.2 (24.4, 33.4) | 27.7 (24.1, 33.1) | 29.8 (25.7, 35.3) | 0.006 |

| BMI Category | 0.037 | |||

| Normal weight BMI<25 | 180 (27.9%) | 154 (30.0%) | 26 (19.5%) | |

| Overweight 25<=BMI<30 | 200 (31.0%) | 158 (30.8%) | 42 (31.6%) | |

| Obese BMI>=30 | 266 (41.2%) | 201 (39.2%) | 65 (48.9%) | |

| Waist circumference (at the umbilicus) | 107.8 ± 16.8 | 106.9 ± 16.3 | 113.3 ± 18.8 | 0.023 |

| Waist circumference (at largest diameter) | 109.3 ± 17.6 | 108.4 ± 16.8 | 115.9 ± 21.3 | 0.012 |

| Hip circumference | 105.0 ± 16.9 | 104.4 ± 15.3 | 109.0 ± 25.1 | 0.114 |

| Mid-upper arm circumference (between shoulder and elbow) | 27.4 ± 5.7 | 27.3 ± 5.9 | 27.9 ± 4.8 | 0.396 |

| Waist-Hip Ratio | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.027 |

| Education status | 0.145 | |||

| No college education | 269 (41.2%) | 209 (39.8%) | 60 (46.9%) | |

| College education | 384 (58.8%) | 316 (60.2%) | 68 (53.1%) | |

| Marital status | 0.725 | |||

| Not married | 412 (60.1%) | 332 (60.5%) | 80 (58.8%) | |

| Married | 273 (39.9%) | 217 (39.5%) | 56 (41.2%) | |

| Study completion status | <.001 | |||

| Did not complete | 409 (71.1%) | 266 (61.6%) | 143 (100.0%) | |

| Completed | 166 (28.9%) | 166 (38.4%) | ||

| Main reason for early discontinuation | <.001 | |||

| No longer meets inclusion/exclusion criteria | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | ||

| Death | 173 (42.3%) | 33 (12.4%) | 140 (97.9%) | |

| Liver Transplant | 80 (19.6%) | 80 (30.1%) | ||

| Other reason(s) | 19 (4.6%) | 18 (6.8%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Patient lost to follow-up | 110 (26.9%) | 109 (41.0%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Patient withdrew consent | 26 (6.4%) | 25 (9.4%) | 1 (0.7%) | |

| Hospitalized due to alcoholic hepatitis within 1 year prior to baseline visit | 0.801 | |||

| No | 436 (62.9%) | 346 (62.7%) | 90 (63.8%) | |

| Yes | 257 (37.1%) | 206 (37.3%) | 51 (36.2%) | |

| Age at first drink (mean±SD) | 18.6 ± 5.9 | 18.3 ± 5.5 | 19.8 ± 7.2 | 0.012 |

| Alcohol use at baseline | 0.712 | |||

| No | 123 (19.8%) | 102 (20.1%) | 21 (18.6%) | |

| Yes | 497 (80.2%) | 405 (79.9%) | 92 (81.4%) | |

| Steroid use | 0.449 | |||

| Never | 533 (75.2%) | 422 (74.6%) | 111 (77.6%) | |

| At least once | 176 (24.8%) | 144 (25.4%) | 32 (22.4%) | |

| Liver biopsy data available | 0.778 | |||

| No/Not done | 690 (97.3%) | 550 (97.2%) | 140 (97.9%) | |

| Yes | 19 (2.7%) | 16 (2.8%) | 3 (2.1%) | |

| History of cirrhosis | <.001 | |||

| No | 658 (92.8%) | 549 (97.0%) | 109 (76.2%) | |

| Yes | 51 (7.2%) | 17 (3.0%) | 34 (23.8%) | |

| History of liver transplant | <.001 | |||

| No | 629 (88.7%) | 486 (85.9%) | 143 (100.0%) | |

| Yes | 80 (11.3%) | 80 (14.1%) | ||

| MELD Score | 26.4 ± 8.3 | 25.0 ± 7.9 | 31.9 ± 7.8 | <.001 |

| MELD Score Classification | <.001 | |||

| MELD score < 20 | 148 (21.2%) | 143 (25.8%) | 5 (3.5%) | |

| MELD score 20–25 | 220 (31.5%) | 194 (35.0%) | 26 (18.2%) | |

| MELD score 26–30 | 135 (19.3%) | 104 (18.7%) | 31 (21.7%) | |

| MELD score >30 | 195 (27.9%) | 114 (20.5%) | 81 (56.6%) | |

| Child-Pugh Score | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 10.1 ± 1.8 | 11.0 ± 1.7 | <.001 |

| Maddrey’s Discriminant Function | 54.9 ± 35.7 | 49.4 ± 32.7 | 75.9 ± 38.9 | <.001 |

| APRI | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 3.0 ± 3.1 | 4.3 ± 4.3 | <.001 |

| Estimated GFR (MDRD) | 74.0 ± 39.7 | 79.5 ± 39.6 | 52.6 ± 31.8 | <.001 |

| Albumin | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 0.780 |

| Total Bilirubin | 17.4 ± 11.7 | 15.5 ± 10.8 | 24.7 ± 12.1 | <.001 |

| Direct Bilirubin | 12.1 ± 8.6 | 10.9 ± 8.3 | 16.7 ± 8.2 | <.001 |

| Creatinine | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 1.3 ± 1.5 | 2.2 ± 2.1 | <.001 |

| ALT | 48.7 ± 34.4 | 47.6 ± 32.8 | 53.3 ± 39.5 | 0.072 |

| AST | 127.8 ± 73.6 | 125.8 ± 69.9 | 135.9 ± 86.4 | 0.141 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 181.8 ± 112.0 | 186.4 ± 118.3 | 163.8 ± 80.5 | 0.032 |

| Total Protein | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 5.6 ± 0.9 | 0.003 |

| Hemoglobin | 9.4 ± 1.8 | 9.4 ± 1.7 | 9.1 ± 1.9 | 0.029 |

| Total WBC (x 10^9 /L) | 12.8 ± 8.4 | 12.0 ± 7.6 | 15.9 ± 10.6 | <.001 |

| Platelet Count (10^9 /L) | 136.9 ± 83.4 | 141.8 ± 83.9 | 118.0 ± 78.7 | 0.002 |

| MCV | 100.7 ± 8.8 | 101.0 ± 8.9 | 99.5 ± 8.3 | 0.074 |

| INR (International Normalized Ratio): | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | <.001 |

| Prothrombin time (PT): | 21.6 ± 6.7 | 20.8 ± 6.2 | 24.6 ± 7.7 | <.001 |

| MAP | 83.0 ± 11.5 | 84.1 ± 11.3 | 78.6 ± 11.5 | <.001 |

Note: Values expressed as n(%), mean±SD or median (Q1,Q3). Abbreviations: AH: Alcoholic hepatitis; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; APRI: Aspartate Aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; INR: International Normalized Ratio; IQR: Interquartile Range; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OBS: Observational; PT: Prothrombin Time; SD: Standard Deviation; WBC: White Blood Cell Count

The estimated effects of patient characteristics on 90-day mortality, expressed as adjusted hazard ratios (aHR) from multivariable Cox regression analysis, showed that college or higher levels of education (aHR= 0.551, 95% CI:[0.352, 0.861], p=0.0094), alkaline phosphatase (aHR=0.997, 95% CI: [0.994, 1.000]; p=0.0328), and MAP (aHR=0.975, 95% CI: [0.952, 0.998]; p=0.0347) were associated with reduced risk of mortality within 90 days. In contrast, higher MELD score (aHR=1.113, 95% CI: [1.08, 1.15], p<0.0001) and total WBC count (aHR=1.026, 95% CI:[1.003, 1.050]; p=0.0295) were associated with increased mortality risk (Table 3). Interestingly, while survival was not different based on steroid use before or at enrollment, those who received steroids during follow-up had significantly better survival (p<0.0001 per log-rank test) (Fig. S3). MELD scores of patients who survived improved over time across all baseline MELD strata (< 20, 20–25, 26–30, and ≥30), with the greatest improvement occurring between weeks 0–4 and 4–12, in those with MELD scores >30 (Fig. S4). In contrast, among those patients with AH who died, MELD either remained stable or worsened in 3 of the 4 MELD strata (Fig S4). None of the HD patients developed AH or MALO at follow-up. The 3 deaths in HD patients were not due to liver-related causes.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of AlcHepNet OBS AH cases stratified by decompensation status

| Overall N=699 | Compensated at baseline N=170 | Decompensated at baseline N=529 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at OBS enrollment | 45.0 ± 10.7 | 44.6 ± 11.0 | 45.2 ± 10.6 | 0.554 |

| Gender assigned at birth | 0.050 | |||

| Female | 288 (41.2%) | 81 (47.6%) | 207 (39.1%) | |

| Male | 411 (58.8%) | 89 (52.4%) | 322 (60.9%) | |

| Race | 0.037 | |||

| Non-white | 93 (13.7%) | 31 (18.5%) | 62 (12.1%) | |

| White | 588 (86.3%) | 137 (81.5%) | 451 (87.9%) | |

| BMI (mean) | 29.6 ± 7.6 | 29.5 ± 8.2 | 29.6 ± 7.4 | 0.852 |

| BMI (median) | 28.2 (24.4, 33.4) | 27.9 (23.2, 33.4) | 28.2 (24.7, 33.4) | 0.418 |

| BMI Category | 0.062 | |||

| Normal weight BMI<25 | 180 (28.0%) | 53 (33.3%) | 127 (26.3%) | |

| Overweight 25<=BMI<30 | 198 (30.8%) | 38 (23.9%) | 160 (33.1%) | |

| Obese BMI>=30 | 264 (41.1%) | 68 (42.8%) | 196 (40.6%) | |

| Waist circumference (at the umbilicus) | 107.8 ± 16.8 | 107.3 ± 19.1 | 107.9 ± 16.0 | 0.754 |

| Waist circumference (at largest diameter) | 109.3 ± 17.6 | 109.3 ± 20.3 | 109.4 ± 16.7 | 0.984 |

| Hip circumference | 105.0 ± 16.9 | 108.6 ± 19.5 | 103.7 ± 15.7 | 0.028 |

| Mid-upper arm circumference (between shoulder and elbow) | 27.4 ± 5.7 | 28.0 ± 5.0 | 27.2 ± 5.9 | 0.249 |

| Waist-Hip Ratio | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | <.001 |

| Education status | 0.158 | |||

| No college education | 267 (41.4%) | 76 (46.1%) | 191 (39.8%) | |

| College education | 378 (58.6%) | 89 (53.9%) | 289 (60.2%) | |

| Marital status | 0.402 | |||

| Not married | 407 (60.1%) | 105 (62.9%) | 302 (59.2%) | |

| Married | 270 (39.9%) | 62 (37.1%) | 208 (40.8%) | |

| Study completion status | 0.543 | |||

| Did not complete | 405 (71.2%) | 94 (69.1%) | 311 (71.8%) | |

| Completed | 164 (28.8%) | 42 (30.9%) | 122 (28.2%) | |

| Main reason for early discontinuation | 0.077 | |||

| No longer meets inclusion/exclusion criteria | 1 (0.2%) | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Death | 171 (42.2%) | 37 (39.4%) | 134 (43.1%) | |

| Liver Transplant | 80 (19.8%) | 11 (11.7%) | 69 (22.2%) | |

| Other reason(s) | 19 (4.7%) | 5 (5.3%) | 14 (4.5%) | |

| Patient lost to follow-up | 110 (27.2%) | 35 (37.2%) | 75 (24.1%) | |

| Patient withdrew consent | 24 (5.9%) | 6 (6.4%) | 18 (5.8%) | |

| Hospitalized due to alcoholic hepatitis within 1 year prior to baseline visit | 0.011 | |||

| No | 431 (62.8%) | 118 (71.1%) | 313 (60.2%) | |

| Yes | 255 (37.2%) | 48 (28.9%) | 207 (39.8%) | |

| Age of first drink (mean ± SD) | 18.6 ± 5.9 | 18.7 ± 5.8 | 18.6 ± 5.9 | 0.771 |

| Alcohol use at baseline | <.001 | |||

| No | 122 (19.8%) | 12 (8.2%) | 110 (23.5%) | |

| Yes | 493 (80.2%) | 135 (91.8%) | 358 (76.5%) | |

| Steroid use | 0.055 | |||

| Never | 524 (75.0%) | 118 (69.4%) | 406 (76.7%) | |

| At least once | 175 (25.0%) | 52 (30.6%) | 123 (23.3%) | |

| Liver biopsy data available | 0.426 | |||

| No/Not done | 680 (97.3%) | 164 (96.5%) | 516 (97.5%) | |

| Yes | 19 (2.7%) | 6 (3.5%) | 13 (2.5%) | |

| History of cirrhosis | 0.136 | |||

| No | 648 (92.7%) | 162 (95.3%) | 486 (91.9%) | |

| Yes | 51 (7.3%) | 8 (4.7%) | 43 (8.1%) | |

| History of liver transplant | 0.019 | |||

| No | 619 (88.6%) | 159 (93.5%) | 460 (87.0%) | |

| Yes | 80 (11.4%) | 11 (6.5%) | 69 (13.0%) | |

| MELD Score (mean ± SD) | 26.4 ± 8.4 | 23.3 ± 6.9 | 27.5 ± 8.5 | <.001 |

| Meld Score Classification | <.001 | |||

| MELD score < 20 | 148 (21.4%) | 58 (34.3%) | 90 (17.2%) | |

| MELD score 20–25 | 216 (31.2%) | 58 (34.3%) | 158 (30.2%) | |

| MELD score 26–30 | 134 (19.3%) | 26 (15.4%) | 108 (20.6%) | |

| MELD score >30 | 195 (28.1%) | 27 (16.0%) | 168 (32.1%) | |

| Child-Pugh Score | 10.3 ± 1.8 | 9.0 ± 1.6 | 10.7 ± 1.7 | <.001 |

| Maddrey’s Discriminant Function | 54.8 ± 35.8 | 45.5 ± 33.5 | 57.9 ± 36.0 | <.001 |

| APRI | 3.3 ± 3.4 | 3.5 ± 3.0 | 3.2 ± 3.5 | 0.399 |

| Estimated GFR (MDRD) | 73.9 ± 39.7 | 87.5 ± 36.8 | 69.2 ± 39.7 | <.001 |

| Albumin | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 0.066 |

| Total Bilirubin | 17.4 ± 11.7 | 15.1 ± 10.7 | 18.2 ± 11.9 | 0.003 |

| Direct Bilirubin | 12.1 ± 8.6 | 10.5 ± 7.8 | 12.7 ± 8.8 | 0.022 |

| Creatinine | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | <.001 |

| ALT | 48.5 ± 34.2 | 54.8 ± 42.8 | 46.5 ± 30.6 | 0.006 |

| AST | 126.9 ± 70.5 | 148.2 ± 82.1 | 120.0 ± 64.9 | <.001 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 181.9 ± 112.2 | 204.4 ± 125.0 | 174.6 ± 106.9 | 0.003 |

| Total Protein | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 5.7 ± 0.9 | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 9.4 ± 1.8 | 9.7 ± 1.7 | 9.2 ± 1.8 | 0.004 |

| Total WBC (x 10^9 /L) | 12.8 ± 8.4 | 11.1 ± 7.9 | 13.4 ± 8.5 | 0.002 |

| Platelet Count (10^9 /L) | 137.0 ± 83.5 | 146.9 ± 83.3 | 133.8 ± 83.4 | 0.078 |

| MCV | 100.7 ± 8.7 | 99.8 ± 9.5 | 101.1 ± 8.4 | 0.092 |

| INR | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.6 | <.001 |

| PT | 21.5 ± 6.7 | 20.1 ± 6.5 | 22.0 ± 6.7 | <.001 |

| MAP | 82.9 ± 11.5 | 85.2 ± 11.6 | 82.2 ± 11.3 | 0.003 |

| Status at 30 Days | 0.447 | |||

| Alive | 609 (87.1%) | 151 (88.8%) | 458 (86.6%) | |

| Dead | 90 (12.9%) | 19 (11.2%) | 71 (13.4%) | |

| Status at 90 Days | 0.099 | |||

| Alive | 557 (79.7%) | 143 (84.1%) | 414 (78.3%) | |

| Dead | 142 (20.3%) | 27 (15.9%) | 115 (21.7%) | |

| Status at 180 Days | 0.287 | |||

| Alive | 534 (76.4%) | 135 (79.4%) | 399 (75.4%) | |

| Dead | 165 (23.6%) | 35 (20.6%) | 130 (24.6%) |

Note: Values expressed as n(%), mean±SD or median (Q1,Q3). Abbreviations: AH: Alcoholic hepatitis; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; APRI: Aspartate Aminotransferase to Platelet Ratio Index; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; INR: International Normalized Ratio; IQR: Interquartile Range; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; MDRD: Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OBS: Observational; PT: Prothrombin Time; SD: Standard Deviation; WBC: White Blood Cell Count

Patients with AH who had decompensated liver disease (as defined in the Methods section) at baseline compared to those who had compensated liver disease at baseline were more likely to be white (87.9% vs. 81.3%, p=0.028) and more likely to have been hospitalized due to AH within 1 year prior to the baseline visit (39.1% vs. 29.6%). Compensated patients were more likely to report alcohol use at baseline than decompensated patients (92% vs 76%, p<0.001) (Table S5). As expected, liver disease severity scores, as measured by MELD and Child-Pugh, and laboratory chemistry and hematologic values were higher in patients with decompensated disease than in those with compensated disease at baseline (Table S5).

Composite Events of Liver and Alcohol Use (AlcHepNet Composite Index)

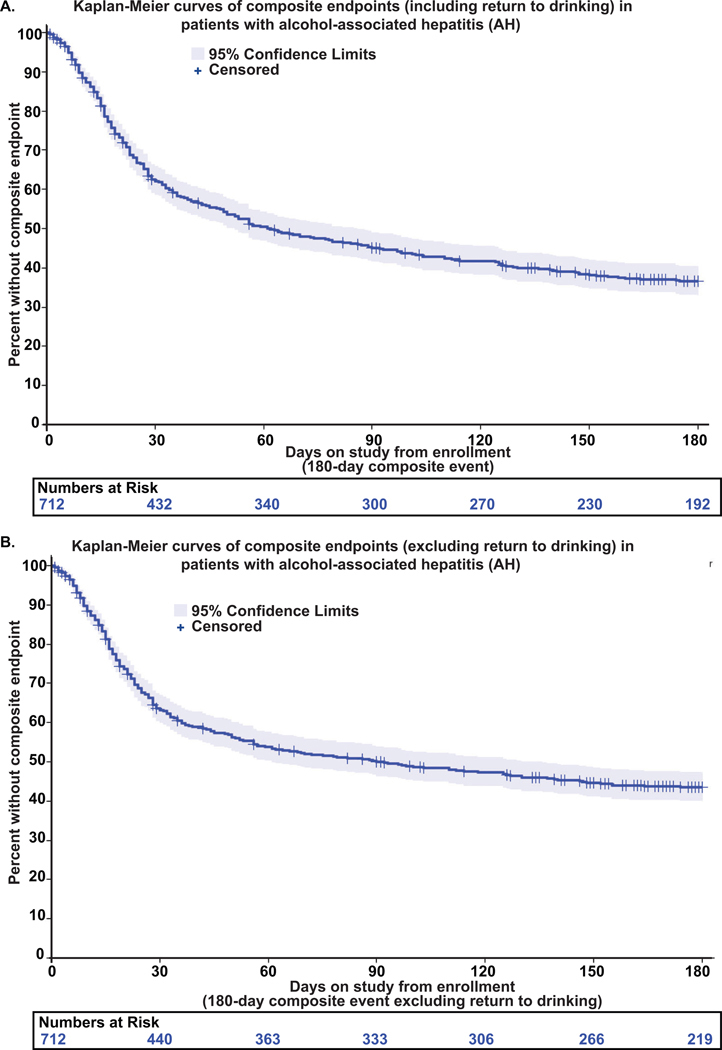

We examined the rate of liver and alcohol use events that had occurred during the 180-day follow-up in patients with AH cases. Sixty-four percent (459 of 712) of patients with AH experienced at least one composite event within that time frame (Table 4). The rate of composite liver events, excluding return to alcohol use, was 55% (393/712) (Table S6). Frequencies of unique combinations of composite events are presented as UpSet plots (Fig S5). Kaplan-Meier curves showed that composite events occurred relatively early during the follow-up for patients with AH – the median time to composite event, including a return to drinking, was 62 days (Fig. 3A). The median time to non-drinking composite event was later (92 days) (Fig. 3B). Of the 712 patients with AH, 86 (12%) received a liver transplant, and 82 (11.5%) of these occurred within 180 days (Table 4). The cumulative incidence rates of liver transplantation at 30 days and 90 days with mortality as a competing risk were 7.6% and 10.9%, respectively (Fig S6). Patients with AH who were white (aHR=12.7, 95% CI: [1.44, 112.10], p=0.022), had college or higher education levels (aHR=2.2, 95% CI: [1.139, 4.258], p=0.019), were married (aHR=3.4, 95% CI: [1.769, 6.548], p=0.0002), or who had higher MELD scores (aHR=1.126, 95% CI: [1.084, 1.17], p<0.0001) were more likely to receive liver transplantation. Since LT is an option for patients who do not recompensate, we identified the rate of recompensation. Among the 712 patients with AH, 246 (35%) experienced a change in MELD score ≤5 points, the time from enrollment to the first observed MELD reduction of this magnitude was calculated as the difference between the visit date (Week 4, Week 12, or Week 24) and the enrollment date (Table S7; Table S8) that showed that recompensation occurred relatively early but given that this was not an a priori outcome, this timing should be interpreted as an approximation and not the exact date of MELD improvement.

Table 4.

Cox model for AlcHepNet OBS AH cases (90-day mortality)

| Maximum Likelihood Estimates | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | DF | Parameter Estimate | Standard Error | Chi-Square | Pr > ChiSq | Hazard Ratio | 95% Hazard Ratio Confidence Limits | |

| Age at OBS enrollment | 1 | 0.02064 | 0.01115 | 3.4304 | 0.0640 | 1.021 | 0.999 | 1.043 |

| Gender assigned at birth: Male | 1 | −0.30578 | 0.28541 | 1.1478 | 0.2840 | 0.737 | 0.421 | 1.289 |

| Race: White | 1 | −0.43163 | 0.34616 | 1.5548 | 0.2124 | 0.649 | 0.330 | 1.280 |

| BMI | 1 | 0.00567 | 0.01565 | 0.1310 | 0.7174 | 1.006 | 0.975 | 1.037 |

| Education status: College education | 1 | −0.64032 | 0.23804 | 7.2358 | 0.0071 | 0.527 | 0.331 | 0.840 |

| Marital status: Married | 1 | 0.21169 | 0.23844 | 0.7882 | 0.3746 | 1.236 | 0.774 | 1.972 |

| Age of first drink | 1 | 0.01205 | 0.01772 | 0.4628 | 0.4963 | 1.012 | 0.978 | 1.048 |

| Alcohol use at baseline: Yes | 1 | 0.14053 | 0.30834 | 0.2077 | 0.6486 | 1.151 | 0.629 | 2.106 |

| Steroid use: At least once | 1 | −0.15757 | 0.27697 | 0.3237 | 0.5694 | 0.854 | 0.496 | 1.470 |

| MELD score | 1 | 0.09580 | 0.01641 | 34.0910 | <.0001 | 1.101 | 1.066 | 1.137 |

| Albumin | 1 | 0.06117 | 0.21135 | 0.0838 | 0.7722 | 1.063 | 0.703 | 1.609 |

| ALT | 1 | 0.00686 | 0.00459 | 2.2342 | 0.1350 | 1.007 | 0.998 | 1.016 |

| AST | 1 | 0.00155 | 0.00199 | 0.6017 | 0.4379 | 1.002 | 0.998 | 1.005 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 1 | −0.00445 | 0.00180 | 6.1452 | 0.0132 | 0.996 | 0.992 | 0.999 |

| Total Protein | 1 | −0.07420 | 0.14270 | 0.2704 | 0.6031 | 0.928 | 0.702 | 1.228 |

| Hemoglobin | 1 | 0.05679 | 0.07780 | 0.5329 | 0.4654 | 1.058 | 0.909 | 1.233 |

| Total WBC (x 10^9 /L) | 1 | 0.03518 | 0.01237 | 8.0809 | 0.0045 | 1.036 | 1.011 | 1.061 |

| Platelet Count (10^9 /L) | 1 | −0.00149 | 0.00154 | 0.9351 | 0.3335 | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.002 |

| MCV | 1 | −0.02193 | 0.01332 | 2.7107 | 0.0997 | 0.978 | 0.953 | 1.004 |

| MAP | 1 | −0.03040 | 0.01236 | 6.0485 | 0.0139 | 0.970 | 0.947 | 0.994 |

Abbreviations: AH: Alcoholic hepatitis; ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; BMI: Body Mass Index; MAP: Mean Arterial Pressure; MCV: Mean Corpuscular Volume; MELD: Model for End-Stage Liver Disease; OBS: Observational; Pr > ChiSq: Probability greater than Chi-Square; WBC: White Blood Cell Count

Fig. 3.

(A) Kaplan-Meier curves of composite endpoints (including return to drinking) within 180 days among patients with AH. (B) Kaplan-Meier curves of composite endpoints (excluding return to drinking) within 180 days among patients with AH.

Alcohol use at baseline was associated with a reduced chance of liver transplant (aHR=0.471, 95% CI: [0.244, 0.909], p=0.025) (Table S9). Patients with moderate AH had clinically significant mortality at Days 90 and 180 (Table S10), demonstrating the need for treatment of both ALD and AUD in patients with moderate AH.

DISCUSSION

Despite significant public health initiatives and disease-focused supportive care, clinical management of AH remains challenging, with a high mortality rate within six months of diagnosis 26. Herein, we conducted a large multicenter observational study to examine the natural history of AH using the current NIAAA consensus definition with prospective follow-up for six months 24. A total of 232 deaths occurred in 712 patients with AH; approximately 14% of patients died within 30 days, 21.5% within 90 days, and 25.7% died within 180 days. The 90-day mortality varied proportionately with the baseline MELD score. Deaths were seen primarily in those with MELD scores> 30 27,28. As the Kaplan-Meier estimates showed, in patients with severe AH (MELD≥20), most deaths occurred in the first month and a half. Mortality in patients with mAH (MELD<20) was clinically significant, exceeding 8% at 6 months. Liver decompensation or multiorgan failure, infection/sepsis, and renal failure were the leading causes of death as recorded for the study. Preventing these events should be considered a high priority in the medical management of severe AH.

Clinically meaningful outcomes beyond mortality, including severe complications of liver disease and RTD offer a more comprehensive measure of patient outcomes. To identify the progression of liver disease, we used a composite outcome measure that included indicators of liver decompensation as defined by the Baveno VII conference (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and hepatorenal syndrome) 29, death, liver transplantation, liver-related hospitalizations, increase in MELD ≥ 5 and early RTD, recognizing that death alone fails to capture the full complexity of patient outcomes. Even though MELD is primarily a score for prognosis in liver disease, we used an increase of ≥ 5 points on MELD as a surrogate for worsening hepatic function, since details of hepatic injury or recovery patterns were not documented as part of protocol evaluation.

Incorporating early RTD, a critical factor influencing the prognosis of AH beyond the 180-day follow-up in the present study, our composite endpoint is likely to reflect patient risk more accurately. Even though early RTD is not a liver-related outcome, given the recognized significance in AH as reported by others25, our composite endpoint is likely to be a more comprehensive and sensitive predictor of outcomes than measures used in previous studies, pending verification in future prospective studies. We did not consider alcohol use as a covariate because, in patients with AH, alcohol use is a risk factor for future MALOs generally beyond 6 months, with early mortality being related to the severity of liver injury at initial evaluation25. Inclusion of liver transplantation (LT) in the composite index accounts for the complex influence of treatment(s) for liver injury on both survival and the need for ongoing medical care. While LT can be considered a failure of other treatment options, it can also be interpreted as a partial success of care, as the patient survives long enough for transplantation to be a viable option. Another potential interpretation is that LT is a response to a low rate of recompensation as reported in patients with ALD, recent alcohol use, and high MELD scores30,31. Given the low numbers of subjects with LT in our cohort, future, longer-term, larger studies are needed to prospectively confirm previously reported retrospective data. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that while transplantation and supportive care may prevent death, they still reflect significant morbidity. Statistically, composite endpoints can enhance analytical power and mitigate biases due to competing risks. For these reasons, composite endpoints have been used in major clinical trials in other diseases32–34. The current study represents an attempt to use a composite endpoint in research specifically related to AH. By doing so, we aim to increase the clinical relevance of study outcomes with the broader concerns of healthcare providers and patients, who are focused on more than survival alone.

Data from this large observational cohort showed that 64% of patients experienced an event captured in the AlcHepNet Composite Index. Even when excluding alcohol use, 55% of AH patients experienced composite liver events within 180 days. The high composite event rates show the importance of more comprehensive, patient-centered care models. Optimizing the management of both liver disease and alcohol use will require early intervention, integrated care, and long-term follow-up strategies. Specifically, early integrated intervention addressing both AH and AUD can potentially improve short- and long-term outcomes. A priority should be placed on providing evidence-based medical treatment, psychological support, and social services for patients with AH and AUD. Our approach incorporates treatment goals that focus on both survival and reducing morbidity to improve quality of life. Given the recognized contribution of RTD to both mortality and liver-related outcomes,25 this event was included in the AlcHepNet composite index. The impact of severity of RTD, and the effect of AUD treatment on outcomes need to be evaluated in future prospective studies.

Our study confirmed that among the factors associated with AH mortality, higher MELD scores, higher total white blood cell counts (WBC), lower mean arterial pressure (MAP), and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels were associated with worse survival, as suggested earlier by others 15,35–39. Among sociodemographic factors, having less than a college-level education was associated with increased mortality. It is unclear whether this finding reflects disparities in access to care and health literacy or is part of the broader impact of social determinants of health. Regardless of whether these factors are the cause or effect of outcomes, several factors influence mortality in AH. While biological factors may aid in risk stratification, sociodemographic factors can be used to target the population at risk. Recent data provide conflicting results on the impact of steroid therapy on AH12,14,40. In our observational cohort, survival was not different in patients treated with steroids before or at enrollment but was higher in those who received steroids during follow-up (p<0.0001). These data should, however, be interpreted in the context that steroid use was based on clinical decisions and steroid use before/at enrollment, which was not continued, was likely a “treatment failure” at enrollment, while “steroid naive” patients benefited from continued treatment. Interestingly, mortality rates in our prospective cohort are similar to those reported in the STOPAH study at 28 (16%) and 90 days (29%), and overall mortality is related to the MELD scores, even in patients with moderate AH, as reported by others11,41. Our observation that the amount of alcohol consumption was lower than in heavy drinkers and that the quantity of alcohol consumed in the past did not relate to the severity of AH or early mortality was consistent with prior reports42. These observations may be due to other factors that contribute to the severity and outcomes of AH37.

Major strengths of the study include a prospective, multicenter design that allows for the inclusion of composite clinical outcomes and the generalizability of the findings. The inclusion of patients with both moderate and severe AH provides a more comprehensive analysis of the spectrum of this disease. A potential limitation of the study is the relatively infrequent follow-up, which may have contributed to the loss of follow-up in some study participants. Limited follow-up schedules made documenting the precise timing of the clinical events of interest, as well as the exact time of onset of symptoms, challenging. Even though some patients were treated briefly with corticosteroids before enrollment, our cohort included both “responders” and “non-responders”. There were 111 patients who were treated with steroids prior to enrollment, in whom treatment was not continued during the study. This could explain better outcomes in patients in whom steroid therapy was initiated after enrollment, because patients who continued to receive steroids were more likely to be responders to the initial treatment. The exact timing of initiation of steroid therapy in relation to the onset of AH symptoms and the decision to refer to our medical centers was not consistently documented. Given these limitations and the lack of randomization to treatments, we cannot draw definitive conclusions about the effects of the treatments that patients received and will be part of future studies. The impact of abstinence and RTD in contributing to adverse long- and short-term outcomes is well recognized in the context of AH and decompensated ALD cirrhosis in a number of retrospective analyses43,44. Despite the prospective nature of the present studies, the primary aim was not to specifically determine the impact of the severity of AUD, details of alcohol abstinence, or remission on outcomes. In the present study, we defined abstinence as a binary outcome and recognize the limitations of this measure. Also, recompensation was defined as a reduction in MELD score as a surrogate measure, since resolution of ascites, encephalopathy, and portal hypertensive bleeding was not precisely documented/adjudicated. The time of recompensation was based on protocol evaluation and cannot be interpreted as a precise time of MELD reduction. However, our data do suggest that in recompensation occurred relatively early in AH patients who recompensated.

In summary, the current study allowed for the development of the AlcHepNet Composite index for use as an endpoint in future studies of AH. By doing so, we aim to enhance clinical relevance by aligning study outcomes with the broader concerns of healthcare providers, patients, and policy makers who must consider outcomes beyond survival alone. This large, multicenter observational study in a contemporary cohort of patients with AH identified a high incidence of composite liver and alcohol use events, highlighting the urgent need to prevent liver decompensation and RTD. Our findings enable investigators to design studies specifically targeting these contributors to both outcomes and adherence to treatment protocols in the future, as recommended in a recent consensus document16.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by the National Institutes of Health grants 5 U01 AA 026976, UO1 AA026976 (all authors). P50 AA024333; R01 AA021890; 3U01AA026976 – 03S1; to SD; NIH K08 AA028794 to NW. P50AA024337, P20GM1113226, U01AA026980, 2I01CX002219–05A2 to CM.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest. Naga Chalasani has consulting agreements with Madrigal, Zydus, Altimmune, Ipsen, Biomed Fusion, GSK, Pfizer, Akero, and Boston Pharmaceuticals. He receives research support from Exact Sciences, Boehringer-Ingelheim. He has equity in Avant Sante, a contract research organization, and Heligenics, a drug discovery start-up company.

References

- 1.Aslam A, Kwo PY. Epidemiology and Disease Burden of Alcohol Associated Liver Disease. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2023;13:88–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jceh.2022.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guirguis J, Chhatwal J, Dasarathy J, Rivas J, McMichael D, Nagy LE, McCullough AJ, Dasarathy S. Clinical impact of alcohol-related cirrhosis in the next decade: estimates based on current epidemiological trends in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2015;39:2085–2094. doi: 10.1111/acer.12887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang DQ, Mathurin P, Cortez-Pinto H, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of alcohol-associated cirrhosis and HCC: trends, projections and risk factors. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;20:37–49. doi: 10.1038/s41575-022-00688-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niu X, Zhu L, Xu Y, Zhang M, Hao Y, Ma L, Li Y, Xing H. Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of alcohol related liver diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:859. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15749-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sengupta S, Anand A, Lopez R, Weleff J, Wang PR, Bellar A, Attaway A, Welch N, Dasarathy S. Emergency services utilization by patients with alcohol-associated hepatitis: An analysis of national trends. Alcohol Clin Exp Res (Hoboken). 2024;48:98–109. doi: 10.1111/acer.15223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hosseini N, Shor J, Szabo G. Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54:408–416. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osna NA, Donohue TM Jr., Kharbanda KK. Alcoholic Liver Disease: Pathogenesis and Current Management. Alcohol Res. 2017;38:147–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu W, Gawrieh S, Dasarathy S, Mitchell MC, Simonetto DA, Patidar KR, McClain CJ, Bataller R, Szabo G, Tang Q, et al. Design of a multicenter randomized clinical trial for treatment of Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;32:101074. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dasarathy S, Mitchell MC, Barton B, McClain CJ, Szabo G, Nagy LE, Radaeva S, McCullough AJ. Design and rationale of a multicenter defeat alcoholic steatohepatitis trial: (DASH) randomized clinical trial to treat alcohol-associated hepatitis. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;96:106094. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2020.106094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forrest E, Mellor J, Stanton L, Bowers M, Ryder P, Austin A, Day C, Gleeson D, O’Grady J, Masson S, et al. Steroids or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis (STOPAH): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:262. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1619–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szabo G, Mitchell M, McClain CJ, Dasarathy S, Barton B, McCullough AJ, Nagy LE, Kroll-Desrosiers A, Tornai D, Min HA, et al. IL-1 receptor antagonist plus pentoxifylline and zinc for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology. 2022;76:1058–1068. doi: 10.1002/hep.32478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gawrieh S, Dasarathy S, Tu W, Kamath PS, Chalasani NP, McClain CJ, Bataller R, Szabo G, Tang Q, Radaeva S, et al. Randomized trial of anakinra plus zinc vs. prednisone for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2024;80:684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, Austin A, Bowers M, Day CP, Downs N, Gleeson D, MacGilchrist A, Grant A. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosseini N, Shor J, Szabo G. Alcoholic hepatitis: a review. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2019;54:408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee BP, Witkiewitz K, Mellinger J, Anania FA, Bataller R, Cotter TG, Curtis B, Dasarathy S, DeMartini KS, Diamond I, et al. Designing clinical trials to address alcohol use and alcohol-associated liver disease: an expert panel Consensus Statement. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21:626–645. doi: 10.1038/s41575-024-00936-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liangpunsakul S Clinical characteristics and mortality of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:714–719. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181fdef1d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur B, Rosenblatt R, Sundaram V. Infections in Alcoholic Hepatitis. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022;10:718–725. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2022.00024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Cola S, Gazda J, Lapenna L, Ceccarelli G, Merli M. Infection prevention and control programme and COVID-19 measures: Effects on hospital-acquired infections in patients with cirrhosis. JHEP Reports. 2023;5:100703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lourens S, Sunjaya DB, Singal A, Liangpunsakul S, Puri P, Sanyal A, Ren X, Gores GJ, Radaeva S, Chalasani N, et al. Acute Alcoholic Hepatitis: Natural History and Predictors of Mortality Using a Multicenter Prospective Study. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2017;1:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang Y, Akbari C, Dodd M, Zhang X, Wang T, Jemielita T, Fernandes G, Engel SS, Nasr P, Vessby J, et al. Association between longitudinal biomarkers and major adverse liver outcomes in patients with non-cirrhotic metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Hepatology. 2025;81:1501–1511. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000001045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tu W, Gawrieh S, Dasarathy S, Mitchell MC, Simonetto DA, Patidar KR, McClain CJ, Bataller R, Szabo G, Tang Q. Design of a multicenter randomized clinical trial for treatment of Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis. Contemporary Clinical Trials Communications. 2023;32:101074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dasarathy S, Tu W, Bellar A, Welch N, Kettler C, Tang Q, Liangpunsakul S, Gawrieh S, Radaeva S, Mitchell M. Development and evaluation of objective trial performance metrics for multisite clinical studies: Experience from the AlcHep Network. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2024;138:107437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crabb DW, Bataller R, Chalasani NP, Kamath PS, Lucey M, Mathurin P, McClain C, McCullough A, Mitchell MC, Morgan TR, et al. Standard Definitions and Common Data Elements for Clinical Trials in Patients With Alcoholic Hepatitis: Recommendation From the NIAAA Alcoholic Hepatitis Consortia. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:785–790. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Louvet A, Labreuche J, Artru F, Bouthors A, Rolland B, Saffers P, Lollivier J, Lemaitre E, Dharancy S, Lassailly G, et al. Main drivers of outcome differ between short term and long term in severe alcoholic hepatitis: A prospective study. Hepatology. 2017;66:1464–1473. doi: 10.1002/hep.29240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Connor L, Dean J, McNett M, Tydings DM, Shrout A, Gorsuch PF, Hole A, Moore L, Brown R, Melnyk BM, et al. Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2023;20:6–15. doi: 10.1111/wvn.12621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D’Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33:464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singal AK, Kamath PS. Model for end-stage liver disease. Journal of clinical and experimental hepatology. 2013;3:50–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jophlin LL, Singal AK, Bataller R, Wong RJ, Sauer BG, Terrault NA, Shah VH. ACG clinical guideline: alcohol-associated liver disease. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. 2024;119:30–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsu CC, Dodge JL, Weinberg E, Im G, Ko J, Davis W, Rutledge S, Dukewich M, Shoreibah M, Aryan M, et al. Multicentered study of patient outcomes after declined for early liver transplantation in severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology. 2023;77:1253–1262. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musto J, Stanfield D, Ley D, Lucey MR, Eickhoff J, Rice JP. Recovery and outcomes of patients denied early liver transplantation for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Hepatology. 2022;75:104–114. doi: 10.1002/hep.32110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitt B, Filippatos G, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Bakris GL, Rossing P, Joseph A, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P. Cardiovascular events with finerenone in kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385:2252–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. New England journal of medicine. 2020;383:2219–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Group SR. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;373:2103–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, Wiesner RH, Kim WR, Menon KN, Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Shah V. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forrest E, Evans C, Stewart S, Phillips M, Oo YH, McAvoy N, Fisher N, Singhal S, Brind A, Haydon G. Analysis of factors predictive of mortality in alcoholic hepatitis and derivation and validation of the Glasgow alcoholic hepatitis score. Gut. 2005;54:1174–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pang JX, Ross E, Borman MA, Zimmer S, Kaplan GG, Heitman SJ, Swain MG, Burak K, Quan H, Myers RP. Risk factors for mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis and assessment of prognostic models: a population‐based study. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;29:131–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasztelan-Szczerbinska B, Slomka M, Celinski K, Szczerbinski M. Alkaline phosphatase: the next independent predictor of the poor 90‐day outcome in alcoholic hepatitis. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:614081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lourens S, Sunjaya DB, Singal A, Liangpunsakul S, Puri P, Sanyal A, Ren X, Gores GJ, Radaeva S, Chalasani N. Acute alcoholic hepatitis: natural history and predictors of mortality using a multicenter prospective study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2017;1:37–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gawrieh S, Dasarathy S, Tu W, Kamath PS, Chalasani NP, McClain CJ, Bataller R, Szabo G, Tang Q, Radaeva S. Randomized-controlled trial of anakinra plus zinc vs. prednisone for severe alcohol-associated hepatitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bennett K, Enki DG, Thursz M, Cramp ME, Dhanda AD. Systematic review with meta-analysis: high mortality in patients with non-severe alcoholic hepatitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:249–257. doi: 10.1111/apt.15376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musto JA, Eickhoff J, Ventura-Cots M, Abraldes JG, Bosques-Padilla F, Verna EC, Brown RS Jr., Vargas V, Altamirano J, Caballeria J, et al. The Level of Alcohol Consumption in the Prior Year Does Not Impact Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Alcohol-Associated Hepatitis. Liver Transpl. 2021;27:1382–1391. doi: 10.1002/lt.26203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hofer BS, Simbrunner B, Hartl L, Jachs M, Balcar L, Paternostro R, Schwabl P, Semmler G, Scheiner B, Trauner M, et al. Hepatic recompensation according to Baveno VII criteria is linked to a significant survival benefit in decompensated alcohol-related cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2023;43:2220–2231. doi: 10.1111/liv.15676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Louvet A, Labreuche J, Dao T, Thevenot T, Oberti F, Bureau C, Paupard T, Nguyen-Khac E, Minello A, Bernard-Chabert B, et al. Effect of Prophylactic Antibiotics on Mortality in Severe Alcohol-Related Hepatitis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;329:1558–1566. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.4902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.