Abstract

Background

Blood pressure management is crucial in critical care, but relationships between pressure patterns and outcomes remain incompletely understood. We analyzed minute-by-minute blood pressure data to develop and validate a novel index quantifying hypotensive exposure burden.

Methods

In this retrospective study using the Salzburg Intensive Care Database, 11,059 ICU admissions with continuous invasive arterial monitoring were analyzed. Heatmaps were constructed from high-resolution hemodynamic data to visualize relationships between blood pressure thresholds (52–120 mmHg), exposure durations (5 min–5 h), and mortality. The Hypotensive Exposure Duration Index (HEDI) was developed to quantify cumulative hypotensive burden by integrating exposure across multiple MAP thresholds. HEDI’s prognostic value was evaluated through nine machine learning algorithms. External validation using the eICU database assessed HEDI’s consistency across different populations.

Results

Non-survivors showed significantly higher HEDI compared to survivors (0.47 [−0.20, 1.43] vs. −0.15 [−0.41, 0.27], p < 0.001). HEDI demonstrated increasing predictive capability, with AUC values rising from 0.624 at 24 h to 0.700 at 72 h post-admission. The Extra Trees classifier achieved exceptional performance (test AUC: 0.843), with HEDI ranking among the top predictive features. Both internal cross-validation and external validation confirmed the model’s robustness, demonstrating HEDI’s prognostic value across different patient populations, including both patients with and without vasopressor use.

Conclusions

HEDI effectively quantifies cumulative hypotensive burden in critically ill patients, demonstrating significant predictive ability for ICU mortality validated across diverse populations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40560-025-00834-7.

Keywords: High-temporal resolution, Blood pressure exposure, Hypotension exposure, Hypotensive exposure duration index, Machine learning

Introduction

Maintaining adequate tissue perfusion is fundamental in critical care, with mean arterial pressure (MAP) serving as a crucial surrogate marker [1–3]. While MAP > 65 mmHg is widely accepted as a safe threshold [4, 5], emerging evidence suggests that the relationship between blood pressure exposure and patient outcomes is more complex than previously recognized [6].

Current approaches to evaluating blood pressure exposure in critically ill patients often focus on specific thresholds or predetermined patterns [7–11], failing to capture the dynamic of hemodynamic variations. Our previous work using hourly blood pressure data from the Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care (MIMIC) database advanced this field by demonstrating that both the magnitude and duration of hypotensive episodes significantly impact patient outcomes, revealing distinct risk patterns through heatmap visualization [12]. However, the hourly data resolution has significant limitations in capturing the true hemodynamic burden experienced by critically ill patients. Rapid blood pressure fluctuations can occur within minutes, with potential cellular and tissue-level consequences even during brief hypotensive episodes [12]. Furthermore, the pattern, frequency, and recovery dynamics of these brief hypotensive episodes may contain important prognostic information that is entirely missed at hourly sampling intervals. To enhance our understanding of these relationships, we leveraged minute-by-minute blood pressure measurements in this study, enabling more precise characterization of exposure patterns. Building upon validated exposure-outcome relationships, we developed the Hypotensive Exposure Duration Index (HEDI), an integrated scoring system that quantifies the cumulative burden of hypotensive episodes in critically ill patients. We hypothesized that this comprehensive assessment would provide superior prognostic value compared to conventional approaches.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This machine learning model was developed using data from the Salzburg Intensive Care Database (SICdb) v1.0.8 [13, 14], a publicly accessible intensive care database collected from four specialized intensive care units at the University Hospital Salzburg between 2013 and 2021. The database contains deidentified clinical information from more than 27,000 ICU admissions, including patient characteristics, vital parameters, laboratory measurements, and medication records. A distinctive feature of SICdb is its dual temporal resolution, preserving both hourly aggregated summaries and minute-by-minute physiological measurements. For external validation of our model, we utilized the eICU Collaborative Research Database [15], which includes data from over 200,000 ICU stays across multiple centers in the United States. The study was conducted in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [16], and database access was granted following completion of required institutional protocols.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed using structured query language (SQL). The following variables were collected: demographic characteristics (age, sex, height, and weight at admission), clinical severity scores; invasive arterial blood pressure measurements, laboratory results, comorbidities, vital signs, and survival status (ICU mortality). Dr. Han Chen has been authorized to extract the data from the SICdb database (RRID:SCR_007345). Dr. Xiao-Yan Ding has been authorized to extract the data from the eICU Collaborative Research Database (RRID:SCR_007345) (database access certification number: XYD 55860595). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Fuzhou University.

Missing data

Extreme MAP values below the 1st percentile were set to the 1st percentile, and those exceeding the 99th percentile were set to the 99th percentile. This same outlier handling approach was applied to all variables. For baseline data (e.g., highest lactate, lowest hemoglobin), missing values were imputed using either the median or mean based on each variable’s distribution (Supplementary File, Table S1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) available invasive MAP data; (2) adult patients ( 18 years); and (3) ICU stay of at least 24 h.

The exclusion criteria were: (1) no invasive MAP monitoring within the first 6 h of ICU admission and (2) outcome data unavailable. In addition, blood pressure data beyond 28 days after ICU stay were excluded from the analysis.

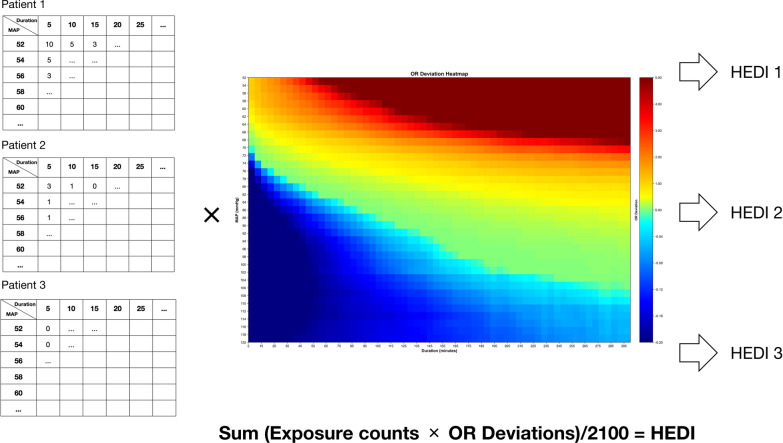

Odds ratio deviation heatmap

The data set was randomly split into training (70%) and internal testing (30%) sets prior to any analysis. The odds ratio (OR) heatmap was generated using only the training cohort data. The analysis of minute-by-minute invasive MAP was performed using predefined thresholds (52–120 mmHg with 2-mmHg intervals), exposure durations from 5 min to 5 h were assessed at 5-min intervals, which was modified from previous study [12, 17]. Briefly, for each MAP threshold–duration combination, exposure events were identified and their frequencies were calculated. The odds ratios were computed as the ratio of exposure frequencies between non-survivors and survivors, and the OR deviations were calculated by subtracting the overall population OR from each specific combination’s OR. A heatmap visualization was generated to display the OR deviations for each combination.

Development of the HEDI

HEDI was developed to quantify the cumulative burden of hypotensive episodes after ICU admission.

As shown in Fig. 1, the development of HEDI consisted of two steps. First, for each patient, exposure frequencies were calculated across all MAP threshold–duration combinations during their ICU stay. Then, individual HEDI scores were computed by multiplying these patient-specific exposure frequencies by their corresponding odds ratios from the population heatmap. The final HEDI scores were normalized by the total number of threshold–duration combinations to ensure comparability across patients. Different temporal HEDI scores were calculated using MAP recordings from corresponding time windows after ICU admission, ranging from 24 to 72 h with 6-h increments. The identical HEDI formula and OR values were applied unchanged to both internal testing and external validation cohorts.

Fig. 1.

Methodology for calculating the hypotension exposure duration index. The figure illustrated the calculation process of hypotension exposure duration index (HEDI) based on individualized blood pressure–duration exposure patterns. A Heat map showing odds ratio (OR) deviations for different combinations of mean arterial pressure (MAP, ranging from 52 to 120 mmHg in 2-mmHg increments) and exposure durations (ranging from 5 to 300 min in 5-min increments). The heat map exhibited distinct zones, where blue regions represented survival benefit, while red regions indicated increased mortality risk. A white contour line was fitted to highlight areas with OR deviation equal to zero, demonstrating the transition boundary between beneficial and harmful hemodynamic exposures. B Examples of HEDI calculation. Three representative patient exposure patterns with varying counts of blood pressure–duration combinations were presented. For each patient, the exposure count at each MAP–duration combination was multiplied by the corresponding OR deviation value from the heat map to generate a weighted score. The sum of all weighted scores was calculated and normalized by dividing by the total number of possible MAP–duration combinations (2,100), resulting in the final HEDI score. This normalization facilitated score interpretation and clinical application. Higher HEDI scores indicated greater cumulative exposure to hemodynamic patterns associated with adverse outcomes. The numbers used in these examples were arbitrary values for illustration purposes only. Empty cells in the patient examples did not indicate absence of values but were simplified for demonstration purposes

HEDI calculation formula:

where i represented MAP thresholds, j represented duration categories, and OR_deviation values were derived exclusively from the training set.

Validation of HEDI

We performed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate the discriminative ability of HEDI for predicting ICU mortality at different timepoints after admission (24–72 h). This allowed us to identify the optimal time window for HEDI assessment and demonstrate the evolution of its predictive performance over time.

Nine machine learning algorithms were applied to evaluate HEDI’s predictive value for ICU mortality: artificial neural network (ANN), decision tree classifier (DT), extra trees classifier (ET), gradient boosting machine (GBM), K-nearest neighbors (KNN), light gradient boosting machine (LightGBM), random forest classifier (RF), support vector machine (SVM), and EXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). Data imbalance was addressed through synthetic minority oversampling technique (SMOTE) to create a balanced training data set. Feature selection process involved: (1) initial ranking of variables using a RF classifier, (2) stepwise feature addition evaluating incremental performance improvement, and (3) termination when performance plateaued at 14 features as measured by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC–ROC). Stratified fivefold cross-validation was employed to maintain outcome distribution across folds. The same fold assignments were used across all algorithms to ensure fair comparison. Hyperparameter optimization was performed using nested cross-validation with an inner threefold CV loop for hyperparameter tuning and an outer fivefold CV loop for performance estimation, preventing data leakage and overfitting.

Model performance was assessed using multiple metrics: AUC–ROC, F1 score, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and Cohen’s Kappa score. Model calibration was evaluated using calibration plots across training, testing, and external validation sets, with separate analyses for patients receiving vasoactive drugs and those not receiving vasoactive drugs. Feature importance was evaluated using mean decrease in impurity in the tree-based models to identify key predictors of mortality. Model interpretability was assessed using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to quantify individual feature contributions to model predictions. SHAP analysis provided both global feature importance and patient-level explanations of model decisions. All predictor variables, including maximum lactate, maximum SOFA score, and cumulative fluid balance, were calculated using data only from the corresponding prediction time window. For 72-h mortality prediction, all predictors were derived from data collected within the first 72 h after ICU admission; similarly, predictors for 48-h mortality predictions were derived from data within the first 48 h. Model calibration was evaluated using calibration plots and the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test. Calibration slopes and intercepts were calculated, with perfect calibration indicated by a slope of 1.0 and intercept of 0.0. Brier scores were computed to assess overall prediction accuracy, with lower scores indicating better performance.

Clinical utility assessment

Decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed to evaluate the clinical utility of the models across different threshold probabilities. Net benefit was calculated as the difference between true positives and false positives weighted by the odds of the threshold probability.

External validation

To assess the generalizability of our findings, we externally validated both the time-dependent performance of HEDI and our machine learning models using the eICU Collaborative Research Database. The eICU database includes high-granularity data, including vital signs, laboratory measurements and outcomes. The inclusion criteria for the external validation cohort mirrored those of the development cohort: (1) available invasive MAP data; (2) adult patients (≥ 18 years); and (3) ICU stay of at least 24 h. Similarly, exclusion criteria were: (1) no invasive MAP monitoring within the first 6 h of ICU admission; (2) outcome data unavailable; and (3) MAP data unavailable or insufficient for accurate hypotension duration calculation, including patients without continuous MAP monitoring and those with monitoring gaps > 2 h. Data extraction and missing data handling of the eICU database followed the same protocol used for the SICdb.

For subgroup analysis in the external validation cohort, we examined HEDI’s predictive performance across different patient populations stratified by vasopressor use. We conducted external validations separately for patients receiving vasopressors, those without vasopressor therapy, and the combined population. Performance metrics were calculated with 95% confidence intervals using bootstrap resampling (n = 1000 iterations).

Sensitivity analysis

To address potential concerns about repeated events and varying observation times, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using a patient-level approach, where each patient contributed at most one event per MAP–duration threshold combination.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges (IQR) and were compared using a Student’s t test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were presented as counts (percentages) and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All analyses were performed using Python (Version 3.12.7). Statistical analyses utilized pandas and scipy libraries. Data visualization was created with Matplotlib. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 11,059 patients were included, of whom 732 (6.6%) died in the ICU (Figure S1). Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. Non-survivors were older (75 [65–80] vs. 70 [60, 75], p < 0.001) and had lower BMI (25.2 [22.8, 29.3] vs. 26.1 [23.2, 29.4], p < 0.001). The maximum SOFA score was significantly higher in non-survivors (7 [5, 9] vs. 4 [3, 6], p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics between survivors and non-survivors

| Survivors (n = 10,327) | Non-survivors (n = 732) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 70 [60, 75] | 75 [65, 80] | < 0.001 |

| Male, (%) | 6638 (64.3%) | 459 (62.7%) | 0.391 |

| Weight, (kg) | 75 [65, 90] | 75 [65, 85] | 0.002 |

| Height, (m) | 1.7 [1.65, 1.75] | 1.7 [1.65, 1.75] | 0.985 |

| BMI, (kg/m2) | 26.1 [23.2, 29.4] | 25.2 [22.8, 29.3] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum SpO2, (%) | 93 [91, 94] | 89 [84, 92] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum RR, (bpm) | 17 [15, 19] | 20 [17, 26] | < 0.001 |

| Maximum T, (℃) | 37.8 [37.5, 38.2] | 37.8 [37.3, 38.4] | 0.718 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 5136 (49.7%) | 344 (47.0%) | 0.163 |

| Renal dysfunction, n (%) | 1450 (14.0%) | 127 (17.3%) | 0.016 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1744 (16.9%) | 114 (15.6%) | 0.386 |

| Lung disease, n (%) | 1262 (12.2%) | 132 (18.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Fluid input, (ml) | 10,141 [7131, 13351] | 13,035 [7658, 19918] | < 0.001 |

| Blood product input, (ml) | 0 [0, 250] | 0 [0, 1250] | < 0.001 |

| Urine output, (ml) | 3960 [2435, 5810] | 2495 [964, 4236] | < 0.001 |

| Fluid balance, (ml) | 5091 [2834, 8117] | 9684 [4413, 17247] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum Hb, (g/dL) | 8.9 [7.8, 10.3] | 8.5 [7.5, 10.1] | < 0.001 |

| Maximum WBC, (× 109/L) | 12.7 [10.0, 16.3] | 15.1 [11.1, 20.2] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum MCV, (fL) | 87.6 [84.4, 90.9] | 87.3 [84.1, 91.4] | 0.518 |

| Minimum MCHC, (g/dL) | 33.6 [32.8, 34.3] | 33.2 [32.3, 34.1] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum MCH, (pg) | 30.0 [28.8, 31.1] | 29.9 [28.8, 30.9] | 0.061 |

| Maximum Lactate, (mmol/L) | 2.49 [1.75, 3.44] | 4.47 [2.68, 8.34] | < 0.001 |

| Maximum Cr, (mg/dL) | 1.00 [0.80, 1.34] | 1.62 [1.10, 2.50] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum PLT, (× 109/L) | 148 [113, 194] | 122 [72, 181] | < 0.001 |

| Maximum SOFA | 4 [3, 6] | 7[5, 9] | < 0.001 |

| Maximum HCT, (%) | 37 [32, 40] | 35 [31, 40] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum BE | −3.7 [−5.9, −1.6] | −7.4 [−12.0, −3.9] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum Mg (mmol/L) | 0.80 [0.74, 0.87] | 0.85 [0.77, 0.96] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum sodium, (mmol/L) | 138 [136, 140] | 138 [135, 141] | 0.215 |

| Minimum pH | 7.33 [7.28, 7.37] | 7.23 [7.13, 7.31] | < 0.001 |

| Blood product transfusion, n (%) | 3283 (31.8%) | 351 (48.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Positive balance, n (%) | 9734 (94.3%) | 704 (96.2%) | 0.036 |

| Negative balance, n (%) | 590 (5.7%) | 28 (3.8%) | 0.039 |

| Vasopressor used, n (%) | 7728 (74.8%) | 638 (87.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperkalemia, n (%) | 1523 (14.7%) | 232 (31.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Hyperthermia, n (%) | 1262 (12.2%) | 172 (23.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Fever, n (%) | 9023 (87.4%) | 601 (82.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Mean MAP, (mmHg) | 75 [70., 81] | 70 [66, 77] | < 0.001 |

| Minimum MAP, (mmHg) | 49 [49, 49] | 49 [49, 49] | 0.032† |

| Maximum MAP, (mmHg) | 120 [120, 120] | 120 [120, 120] | 0.963† |

| TWMAP, (mmHg) | 75 [70, 81] | 70 [66, 77] | < 0.001 |

BE Base Excess, BMI body mass index, bpm breath per minute, Cr Creatinine, Hb Hemoglobin, HCT Hematocrit, HEDI Hypotension Exposure Duration Index, MAP Mean Artery Pressure, MCH Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin, MCHC Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration, MCV Mean Corpuscular Volume, Mg Magnesium, PLT Platelet Count, RR Respiratory Rate, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SpO2 Oxygen Saturation, T Temperature, TWMAP Time Weighted Mean Artery Pressure, WBC: White Blood Cell Count. †Values reflect data after Winsorization at 1st and 99th percentiles for outlier management

Non-survivors showed worse respiratory parameters, with lower minimum SpO₂ (89 [84, 92] vs. 93 [91, 94], p < 0.001) and higher respiratory rates (20 [17, 26] vs. 17 [15, 19], p < 0.001). Laboratory abnormalities in non-survivors included higher maximum lactate (4.47 [2.68, 8.34] vs. 2.49 [1.75, 3.44], p < 0.001), higher maximum creatinine (1.62 [1.10, 2.50] vs. 1.00 [0.80, 1.34], p < 0.001), and lower hemoglobin (8.5 [7.5, 10.1] vs. 8.9 [7.8, 10.3], p < 0.001).

Non-survivors had higher rates of lung disease (18.0% vs. 12.2%, p < 0.001) and renal dysfunction (17.3% vs. 14.0%, p = 0.016), more frequently required vasopressor support (87.2% vs. 74.8%, p < 0.001), and received more fluid (13,035 [7,658, 19,918] vs. 10,141 [7,131, 13,351], p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed in gender distribution or history of hypertension.

MAP exposure pattern analysis

The relationship between MAP exposure patterns and ICU mortality risk was visualized through OR deviation heatmaps (Fig. 1). A white dashed line (OR deviation = 0) divided the heatmap into two distinct regions: the red region representing mortality risk and the blue region indicating survival benefit. The red region (positive OR deviation) extends further into higher MAP values as exposure duration increases, while the blue region (negative OR deviation) is most prominent at higher MAP values and shorter exposure durations.

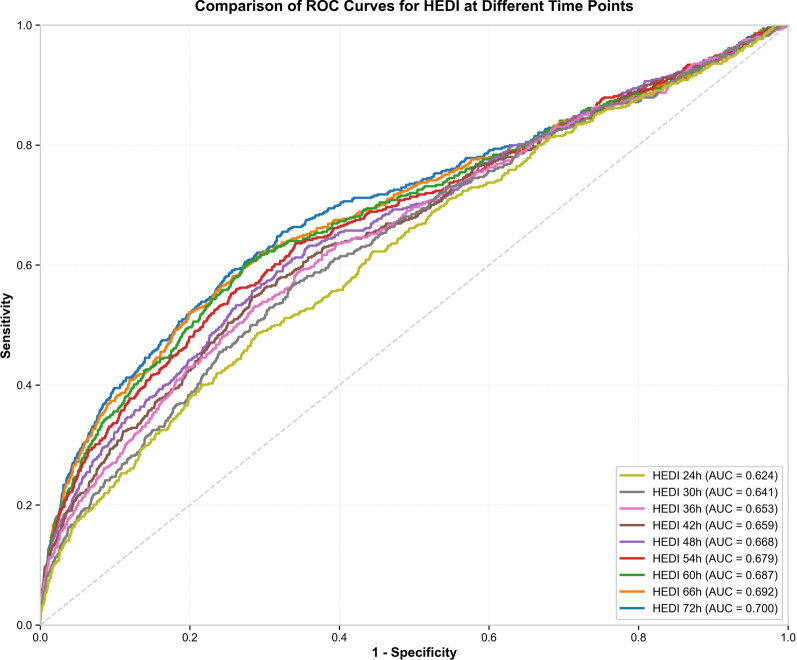

Time-dependent ROC analysis of HEDI

Based on these exposure patterns, we calculated the HEDI, which was significantly higher in non-survivors compared to survivors (0.47 [ − 0.20, 1.43] vs. − 0.15 [− 0.41, 0.27], p < 0.001). The discriminative performance of HEDI for predicting ICU mortality was evaluated at sequential timepoints (Fig. 2). The analysis demonstrated a consistent pattern of increasing predictive capability over time. For the total population, the AUC values progressively increased from 0.624 at 24 h to 0.700 at 72 h after ICU admission. The predictive performance of HEDI improved with each consecutive time interval (Supplementary File, Table S2).

Fig. 2.

ROC curves showing the time-dependent predictive performance of HEDI for ICU mortality in the training cohort (SICdb data set). AUC values increase progressively from 0.624 at 24 h to 0.700 at 72 h after ICU admission

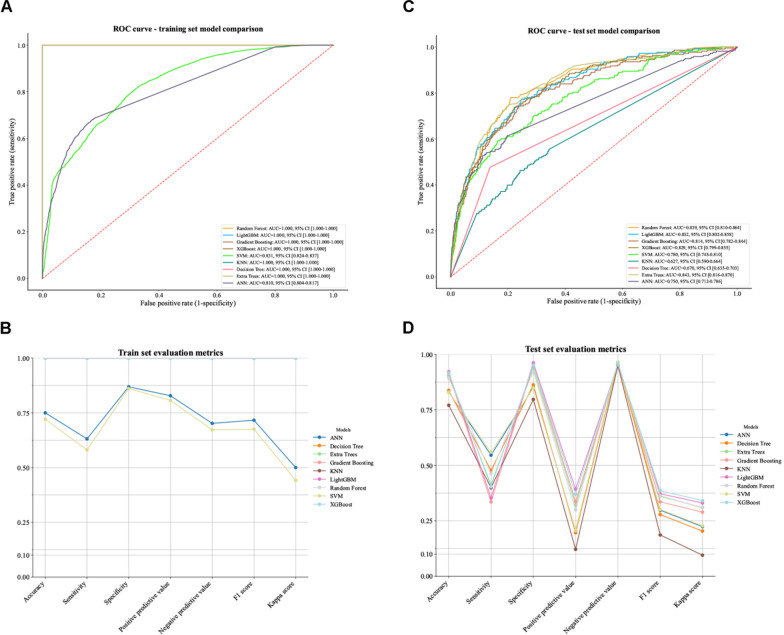

Machine learning analysis

Based on the time-dependent ROC analysis showing optimal discriminative performance at 72 h post-admission (AUC = 0.700), the 72-h HEDI values were selected for machine learning model development. This timepoint was chosen to maximize the predictive capability of the HEDI while maintaining clinical relevance for early intervention.

Feature selection analysis identified 14 optimal predictors for model development (Supplementary File, Figure S2). The 72-h HEDI ranked among the top ten predictors, demonstrating its clinical relevance in mortality prediction. The significant features included age, laboratory parameters (minimum sodium, maximum creatinine), and fluid management indicators. Beyond the top 14 features, additional variables contributed minimally to model performance improvement, justifying the final feature set selection.

Nine machine learning algorithms were evaluated for ICU mortality prediction (Fig. 3). In both training (Fig. 3A, B) and test sets (Fig. 3C, D), the ET model demonstrated the best overall performance. While it showed high discriminative ability on the training set (Fig. 3A, B), more importantly, it achieved superior generalization with the highest test set AUC of 0.843 (95% CI 0.816–0.870, Fig. 3C, D). PR–AUC of 0.337 (95% CI 0.279–0.400, Table S3). The ET model also achieved the lowest Brier score of 0.076 [95% CI 0.071–0.081] in the test set, indicating superior overall prediction accuracy. LightGBM and Random Forest followed as second and third best performers, respectively (Table S3).

Fig. 3.

Performance comparison of machine learning models for predicting ICU mortality. Panel A: ROC curves for nine different machine learning models on the training set, all demonstrating excellent discriminative ability with AUC values exceeding 0.95. Panel B: Comprehensive evaluation metrics for all models on the training set, including accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, F1 score, Kappa score, and ROC AUC. Panel C: ROC curves for the same models applied to the internal test set, maintaining robust performance. Panel D: Evaluation metrics for the internal test set, showing consistent performance across all assessment criteria

Feature importance analysis from ET (Fig. 4A) revealed that while traditional clinical parameters such as maximum lactate level and minimum peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) demonstrated the strongest predictive power, the 72-h HEDI contributed significantly to outcome prediction, ranking 8th among all features. Other influential predictors included minimum arterial pH, maximum SOFA score, fluid input, urine output, and minimum respiratory rate.

Fig. 4.

Feature analysis for ICU mortality prediction. Panel A: Feature importance rankings from the Extra Trees model. Maximum lactate level and minimum peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂) demonstrate the highest predictive value, while the HEDI ranks 8th among the 14 clinical parameters evaluated, confirming its independent clinical value as a mortality predictor. Panel B: SHAP analysis revealing the magnitude and direction of feature contributions to ICU mortality predictions. Results demonstrate that maximum lactate level has the strongest positive impact on mortality prediction, while the SHAP distribution pattern for HEDI shows that higher values are significantly associated with increased mortality risk. This analysis also reveals complex non-linear relationships between certain parameters (such as urine output and fluid input) and outcomes

SHAP summary plots revealed that the 72-h HEDI exhibited a clear directional impact, with higher HEDI values (red) associated with positive SHAP values, indicating increased mortality predictions (Fig. 4B). The magnitude of HEDI’s influence, while not as pronounced as maximum lactate level or SpO₂, showed directionality aligned with its clinical rationale as a marker of hemodynamic dysfunction.

Decision curve analysis demonstrated that the ET model showed positive clinical benefit at low threshold probabilities (0.0–0.20) in the training and external validation sets, but limited benefit in the test set (Figure S3). The model performed best when identifying patients at very high risk (threshold probabilities below 0.15), suggesting potential clinical utility for this specific patient population.

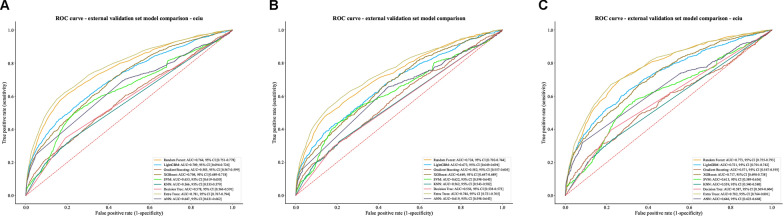

External validation

Following the same inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the training cohort, a total of 13,180 patients were identified for external validation (Supplementary File, Figure S4). The baseline characteristic of external validation cohort is presented in Table S4.

The optimized model Extra Trees was evaluated using three subsets of the external validation cohort. In the total external validation cohort (n = 13,180), the model showed good overall accuracy (0.898 [0.892, 0.903]) and specificity (0.988 [0.986, 0.990]), with an AUC of 0.781 [0.767, 0.794], indicating acceptable discriminative ability. Among patients not receiving vasoactive medications (n = 9,204), the model achieved higher accuracy (0.929 [0.924, 0.934]) and specificity (0.993 [0.991, 0.994]). Whereas in patients receiving vasoactive medications (n = 3,976) while maintaining good accuracy (0.826 [0.814, 0.838]) and specificity (0.977 [0.972, 0.982]), the model demonstrated improved slightly better discriminative performance (AUC = 0.782 [0.764, 0.801]) (Fig. 5). Detailed performance metrics are presented in Table S5. In external validation, the model demonstrated robust clinical utility for patients with vasoactive medications (threshold probability range: 0.1–0.6) and moderate utility for the total cohort (0.1–0.45). In contrast, the model showed limited clinical applicability for patients without vasoactive medications, with only minimal net benefit observed in a narrow threshold range (Figure S3).

Fig. 5.

Extra trees model performance in external validation

Sensitivity analysis (patient-level event definition)

To address concerns regarding patient observation time and repeated events, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using patient-level (PL) event definitions rather than episode-level counting. The PL machine learning analysis largely confirmed the robustness of our findings, with the ET model maintaining superior performance (test set AUC: 0.851, 95% CI [0.824–0.875]) compared to the episode-level approach (AUC: 0.843, 95% CI 0.816–0.870) (Supplementary Figure S5). Feature importance rankings remained consistent, with the 72-h HEDI maintaining its clinical relevance (ranking tenth vs. eighth in episode-level analysis) and traditional clinical parameters retaining their predictive strength (Supplementary Figure S6). External validation yielded comparable discriminative performance across all cohorts (Supplementary Table S6), and decision curve analysis confirmed preserved clinical utility with similar threshold probability ranges for net clinical benefit (Supplementary Figure S7). These results demonstrate that our conclusions are robust to different approaches for handling repeated patient encounters, confirming the clinical validity of the HEDI as a mortality predictor regardless of counting methodology.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were: (1) In this large-scale analysis of high-temporal resolution arterial pressure data, we identified a dynamic relationship between blood pressure thresholds and exposure duration, with mortality risk increasing progressively at lower blood pressure levels and longer exposure durations; (2) The predictive value of HEDI for ICU mortality exhibited a time-dependent pattern, with its discriminative capability progressively strengthening as the MAP monitoring window extended from 24 to 72 h after ICU admission. This consistent trend was observed in both training and validation cohorts, suggesting that HEDI provides enhanced prognostic information regardless of the population studied; (3) Machine learning analysis confirmed HEDI’s contribution to ICU mortality prediction. The developed models incorporating HEDI achieved robust performance and maintained good discriminative capability during external validation, thus establishing HEDI’s generalizable prognostic utility in critical care settings.

Previous studies examining the relationship between hypotension and mortality have been limited by predefined blood pressure thresholds (60, 70, 75 mmHg, etc.) and coarse temporal resolutions (5, 15, or 120 min) [7, 10, 18–20], which may not reflect the complex interplay between blood pressure and patient outcomes. Organ injury is more likely to accumulate progressively as blood pressure decreases, rather than occurring suddenly at a specific threshold [21]. While the 2023 PeriOperative Quality Initiative (POQI) international consensus statement emphasized the importance of considering hypotension duration [22], the optimal approach to quantifying hypotensive burden remains unclear. The relationship between blood pressure and outcomes appears more complex, requiring more refined assessment methods [22, 23]. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that brief, frequent hypotensive episodes may significantly impact outcomes [23]. Most blood pressure measurements rely on intermittent noninvasive monitoring at 5-min intervals, which may underestimate the true incidence of hypotension [24]. Our preliminary work attempted to better understand this relationship through more intensive measurements, but hourly intervals potentially masked important transient exposure events. Therefore, we analyzed the high-temporal resolution (minute by minute) MAP measurements using 5-min intervals across a range of 5–300 min.

The minute-resolution heatmap analysis revealed complex relationships between blood pressure exposure and ICU mortality risk, extending our previous findings with higher temporal precision. High-resolution data demonstrated that mortality risk increased non-linearly with both the intensity and duration of blood pressure deviations. Similar to our previous findings, we observed that achieving target blood pressure alone may be insufficient [12]. In other words, maintaining MAP stability within an optimal range appears crucial for favorable outcomes. Using this high-resolution analytical approach, we have further refined our understanding of the dose–response relationship between blood pressure exposure and clinical outcomes, demonstrating that both the magnitude and duration of hypotension may contribute significantly to patient risk.

The HEDI was developed based on the minute-resolution heatmap. Unlike traditional approaches that use single blood pressure thresholds or fixed exposure durations (such as cumulative time with MAP < 65 mmHg or 5-min episodes) [25], HEDI integrates exposure information across multiple blood pressure thresholds and multiple duration windows, providing a more comprehensive assessment of hypotension exposure burden. Univariate analysis demonstrated significantly higher HEDI values in the mortality group compared to survivors, confirming the association between severe hypotension exposure burden and adverse outcomes. Further ROC curve analysis revealed HEDI’s predictive value for ICU mortality, with a progressive improvement in predictive capability as observation time prolonged (from 24 to 72 h). This time-dependency suggests that the cumulative effect of hemodynamic fluctuations may better reflect tissue perfusion status than single measurements, aligning with recent trends in critical care medicine emphasizing “time-weighted” physiological parameter assessment [26, 27]. While longer observation windows (72 h) provide superior predictive performance due to the capture of more hemodynamic data, this comes with practical tradeoffs. Extended monitoring periods require more complete data sets, which may not be available for all patients, and delay the availability of predictive insights for clinical decision-making. After considering the balance between predictive accuracy and clinical utility, we selected the 72-h timepoint for subsequent machine learning analysis, as it offered optimal discrimination while still allowing for interventions within a clinically relevant timeframe for most ICU patients.

Multiple machine learning algorithms were evaluated, with Extra Trees identified as the optimal model for mortality prediction. Excellent discrimination ability was demonstrated in both training and testing sets, indicating strong classification and generalization capabilities. Feature importance analysis revealed that traditional markers of physiological derangement (maximum lactate, minimum SpO2, minimum pH, and maximum SOFA score) contributed most significantly to predictions. Although not among the top predictors, HEDI outperformed conventional blood pressure monitoring metrics, including minimum MAP and time-weighted MAP. This comparative advantage carries dual significance: first, it confirms that simultaneous consideration of exposure intensity and duration provides greater value than single-threshold approaches; second, it suggests that the cumulative impact of hemodynamic fluctuations is effectively captured, potentially better approximating the physiological process by which hypotension leads to organ injury.

In addition, the predictive capability of HEDI was evaluated across multiple time windows. The 48-h HEDI model demonstrated excellent performance in both internal and external validation, achieving an AUC of 0758, only marginally lower than the 72-h model. Notably, in high-risk populations receiving vasopressors, the 48-h HEDI model maintained an AUC of 0.762, indicating that HEDI provides robust predictive information even during shorter observation periods. Importantly, HEDI consistently maintained its high position in feature importance rankings (Supplementary File, Figs. S8–12), validating its robustness as a prognostic predictor. These findings support HEDI’s potential as an early risk assessment tool providing valuable predictive information within 48 h of ICU admission while confirming that extended observation periods allow HEDI to capture more comprehensive hemodynamic burden information, further improving predictive accuracy. As a dynamic indicator that can be automatically calculated and displayed in real time through integration with modern ICU monitoring systems, HEDI enables continuous risk reassessment. In clinical practice, this characteristic allows HEDI to serve not only for early risk stratification but also for treatment effect evaluation and dynamic prognosis monitoring.

Similar to our observations with univariate HEDI analysis, the selection between 48-h and 72-h timepoints for machine learning model development represents a fundamental tradeoff between feasibility and accuracy. While the 72-h model achieved marginally superior discriminative performance, the 48-h model maintained good predictive capability with the significant advantage of earlier availability. This tradeoff mirrors clinical decision-making processes, where the balance between obtaining more comprehensive data and providing timely interventions must be carefully considered. In practical implementation, healthcare systems might select different timepoints based on their specific patient populations, clinical workflow, and resource availability. This flexibility in application timeframes enhances HEDI’s clinical utility across diverse critical care settings.

External validation results further support HEDI’s clinical utility. In a validation cohort comprising 13,180 patients, our model demonstrated robust predictive performance, particularly in the critically ill subgroup receiving vasopressors. These patients typically represent the most hemodynamically unstable high-risk population with complex treatment strategies and physiological responses. The model maintained performance in this subgroup suggests that the hemodynamic information captured by HEDI exhibits consistency and reliability across populations, further confirming its potential value as a hemodynamic assessment tool. The high accuracy observed in both internal and external validation indicates promising prospects for clinical application.

Several limitations should be considered. First, as an observational study, causal relationships between HEDI and mortality cannot be established. The observed associations may be influenced by unmeasured confounding factors, including variations in treatment strategies, or individualized therapeutic targets. Second, our analysis was restricted to patients with arterial catheter monitoring, who typically represent a more critically ill population, potentially limiting the applicability of our findings to the general ICU population. Third, our analysis used fixed 72-h observation windows without adjusting for individual variations in actual ICU observation time, as patients with shorter stays due to early death or discharge have different hypotensive exposure opportunities compared to those observed for the full duration. Fourth, despite external validation, our validation was confined to data from a specific healthcare system, necessitating broader multicenter validation in future studies. Finally, this study did not evaluate interactions between HEDI and other dynamic physiological parameters (e.g., heart rate variability, vascular resistance changes), which might provide additional prognostic information.

Despite these limitations, this study uniquely features minute-by-minute hemodynamic data, enabling comprehensive analysis of hypotensive exposures across multiple thresholds and durations. Based on these high-resolution measurements, we developed HEDI, which captures the cumulative impact of varying hypotensive intensities on patient outcomes. Through rigorous internal and external validation, this study confirms HEDI’s independent value in predicting mortality risk, particularly among hemodynamically unstable high-risk patients. This novel index surpasses both single-threshold blood pressure monitoring and fixed exposure duration assessments, more accurately reflecting the physiological mechanisms through which hypotensive burden affects outcomes. HEDI demonstrates potential as both a risk stratification tool and a dynamic monitoring indicator, potentially facilitating individualized blood pressure management in critically ill patients and establishing a foundation for precision-medicine in critical care.

Conclusion

HEDI, as a hemodynamic indicator that simultaneously considers both exposure intensity and duration, demonstrates significant value as a predictor variable in prognostic modeling. Our high-resolution analysis of blood pressure exposure patterns provides new insights into the relationship between hypotension exposure and mortality in critical illness. The HEDI offers a promising tool for early risk stratification, though its clinical utility ultimately needs to be validated in prospective interventional studies.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ANN

Artificial neural network

- AUC

Area under curve

- BMI

Body mass index

- DT

Decision tree

- ET

Extra trees

- GBM

Gradient boosting machine

- HEDI

Hypotensive exposure duration index

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- KNN

K-nearest neighbors

- LightGBM

Light gradient boosting machine

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- MIMIC

Multiparameter intelligent monitoring in intensive care

- NPV

Negative predictive value

- OR

Odds ratio

- POQI

PeriOperative quality initiative

- PPV

Positive predictive value

- RF

Random forest

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SICdb

Salzburg intensive care database

- SMOTE

Synthetic minority oversampling technique

- SpO₂

Peripheral oxygen saturation

- SQL

Structured query language

- SOFA

Sequential organ failure assessment

- STROBE

Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology

- SVM

Support vector machine

- XGBoost

EXtreme gradient boosting

Author contributions

HC has significantly shaped the conceptual framework of this work. Throughout the processes of data extraction, analysis, and manuscript drafting, HC offered valuable suggestions and critical feedback, ensuring that the final version was thoroughly reviewed and approved for publication. XYD played a crucial role in data extraction and manuscript drafting, and contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. HPX primarily performed the data analysis and interpretation. JRZ assisted with literature review and reference collection.

Funding

HC is supported by the Youth Top Talent Project of Fujian Provincial Foal Eagle Program. XYD is supported by the Startup Fund for Scientific Research, Fujian Medical University (grant number: 2021QH1290). HPX was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2023J05250) and the Fuzhou Science and Technology Project (2024-S-003).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the publicly available critical care database (eICU database and SICdb version 1.0.8), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. However, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the holder of the database.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study utilized data from two databases: (1) the eICU Collaborative Research Database, which is exempt from institutional review board approval due to the retrospective design, lack of direct patient intervention, and the security schema, for which the re-identification risk was certified as meeting safe harbor standards by an independent privacy expert (Privacert, Cambridge, MA) (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act Certification no. 1031219–2); and (2) the SICdb, which is fully approved by the local ethical commission of the Land Salzburg, Austria (EK Nr: 1115/2021).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Xiao-Yan Ding and Hai-Ping Xu have equally contributed to this work.

References

- 1.Malakar S, Singh SK, Usman K. Optimizing blood pressure management in type 2 diabetes: a comparative investigation of one-time versus periodic lifestyle modification counseling. Cureus. 2024;16(6):e61607. 10.7759/cureus.61607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mistry EA, Hart KW, Davis LT, et al. Blood pressure management after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke: the BEST-II randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;330(9):821–31. 10.1001/jama.2023.14330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welte M, Saugel B, Reuter DA. Perioperative blood pressure management: what is the optimal pressure? Anaesthesist. 2020;69(9):611–22. 10.1007/s00101-020-00767-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21(2):e52–106. 10.1097/pcc.0000000000002198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock 2021. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47(11):1181–247. 10.1007/s00134-021-06506-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cecconi M, Evans L, Levy M, Rhodes A. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):75–87. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)30696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kouz K, Weidemann F, Naebian A, et al. Continuous finger-cuff versus intermittent oscillometric arterial pressure monitoring and hypotension during induction of anesthesia and noncardiac surgery: the DETECT randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2023;139(3):298–308. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zuin M, Rigatelli G, Bongarzoni A, et al. Mean arterial pressure predicts 48 h clinical deterioration in intermediate-high risk patients with acute pulmonary embolism. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2023;12(2):80–6. 10.1093/ehjacc/zuac169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall JC. Choosing the best blood pressure target for vasopressor therapy. JAMA. 2020;323(10):931–3. 10.1001/jama.2019.22526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Lin J, Wu D, Guo X, Li X, Shi S. Optimal mean arterial pressure within 24 hours of admission for patients with intermediate-risk and high-risk pulmonary embolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26:1076029620933944. 10.1177/1076029620933944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin BR, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Shi Q, et al. Blood pressure, readmission, and mortality among patients hospitalized with acute kidney injury. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(5):e2410824. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.10824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding X-Y, Chen Z-Z, Chen H. Both intensity and duration of arterial blood pressure exposure are associated with mortality in critically ill patients: a retrospective database study. Br J Anaesth. 2025;134(4):1193–6. 10.1016/j.bja.2024.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodemund N, Wernly B, Jung C, Cozowicz C, Koköfer A. The Salzburg intensive care database (SICdb): an openly available critical care dataset. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49(6):700–2. 10.1007/s00134-023-07046-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodemund N, Wernly B, Jung C, Cozowicz C, Koköfer A. Harnessing big data in critical care: exploring a new European dataset. Sci Data. 2024;11(1):320. 10.1038/s41597-024-03164-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pollard TJ, Johnson AEW, Raffa JD, Celi LA, Mark RG, Badawi O. The eICU collaborative research database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci Data. 2018;5(1):180178. 10.1038/sdata.2018.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding XY, Chen ZZ, Chen H. Visualizing ICP “Dose” of neurological critical care patients. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50(5):781–3. 10.1007/s00134-024-07424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregory A, Stapelfeldt WH, Khanna AK, et al. Intraoperative hypotension is associated with adverse clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2021;132(6):1654–65. 10.1213/ane.0000000000005250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khanna AK, Kinoshita T, Natarajan A, et al. Association of systolic, diastolic, mean, and pulse pressure with morbidity and mortality in septic ICU patients: a nationwide observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2023;13(1):9. 10.1186/s13613-023-01101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knight J, Hill A, Melnyk V, et al. Intraoperative hypoxia independently associated with the development of acute kidney injury following bilateral orthotopic lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2022;106(4):879–86. 10.1097/tp.0000000000003814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wesselink EM, Wagemakers SH, van Waes JAR, Wanderer JP, van Klei WA, Kappen TH. Associations between intraoperative hypotension, duration of surgery and postoperative myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective single-centre cohort study. Br J Anaesth. 2022;129(4):487–96. 10.1016/j.bja.2022.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saugel B, Fletcher N, Gan TJ, Grocott MPW, Myles PS, Sessler DI. Perioperative Quality Initiative (POQI) international consensus statement on perioperative arterial pressure management. Br J Anaesth. 2024;133(2):264–76. 10.1016/j.bja.2024.04.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saab R, Wu BP, Rivas E, et al. Failure to detect ward hypoxaemia and hypotension: contributions of insufficient assessment frequency and patient arousal during nursing assessments. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127(5):760–8. 10.1016/j.bja.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szrama J, Gradys A, Bartkowiak T, Woźniak A, Kusza K, Molnar Z. Intraoperative hypotension prediction—a proactive perioperative hemodynamic management—a literature review. Medicina (B Aires). 2023. 10.3390/medicina59030491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dupont V, Bonnet-Lebrun AS, Boileve A, et al. Impact of early mean arterial pressure level on severe acute kidney injury occurrence after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Ann Intensive Care. 2022;12(1):69. 10.1186/s13613-022-01045-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z, Zhao X, Wang D, et al. Reliability and accuracy analysis of time-weighted average exposure to heavy metals based on personal exposure. Sci Total Environ. 2022;833:155209. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.155209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maheshwari K, Shimada T, Yang D, et al. Hypotension prediction index for prevention of hypotension during moderate- to high-risk noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(6):1214–22. 10.1097/aln.0000000000003557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the publicly available critical care database (eICU database and SICdb version 1.0.8), but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. However, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the holder of the database.