Abstract

The fission yeast minichromosome loss mutant mcl1-1 was identified in a screen for mutants defective in chromosome segregation. Missegregation of the chromosomes in mcl1-1 mutant cells results from decreased centromeric cohesion between sister chromatids. mcl1+ encodes a β-transducin-like protein with similarity to a family of eukaryotic proteins that includes Ctf4p from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, sepB from Aspergillus nidulans, and AND-1 from humans. The previously identified fungal members of this protein family also have chromosome segregation defects, but they primarily affect DNA metabolism. Chromosomes from mcl1-1 cells were heterogeneous in size or structure on pulsed-field electrophoresis gels and had elongated heterogeneous telomeres. mcl1-1 was lethal in combination with the DNA checkpoint mutations rad3Δ and rad26Δ, demonstrating that loss of Mcl1p function leads to DNA damage. mcl1-1 showed an acute sensitivity to DNA damage that affects S-phase progression. It interacts genetically with replication components and causes an S-phase delay when overexpressed. We propose that Mcl1p, like Ctf4p, has a role in regulating DNA replication complexes.

Genomic instability arises from inaccuracies in DNA replication, repair, or segregation. Genetic screens in yeasts have identified many factors required for stable chromosome transmission by assessing the loss of a nonessential minichromosome. Such mutants are valuable tools in our efforts to understand the mechanics of genomic stability, often providing insights into the importance of pathways in chromosome maintenance (21, 35, 42, 43, 53, 63, 67, 78). Recent work on the chromosome transmission fidelity (ctf) mutants (ctf4, ctf7, ctf8, and ctf18) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals a direct link between DNA replication and chromosome segregation through the establishment of sister-chromatid cohesion, i.e., the association between newly replicated strands of DNA (29, 47, 59). In Schizosaccharomyces pombe, sister chromatids are held together by a protein complex minimally composed of Psm1p (Smc1 in S. cerevisiae), Psm3p (Smc3), Psc3p (Scc3), and Rad21p (Scc1) (72, 76). Homologues of these four proteins are found from yeast to humans and appear to be conserved in function (44). The cohesin complex forms a stable association between sister chromatids that facilitates the equal distribution of chromosomes to daughter cells during cell division by constraining the replicated strands from scattering, both before and during mitosis. Additionally, cohesins are important for double-strand break repair and general DNA metabolism; thus, cohesin mutants are sensitive to UV light (UV), γ-irradiation, and replication arrest by hydroxyurea (HU) (39, 73, 86). The regulation of cohesin complexes is essential for eukaryotic genomic stability.

Cohesins are broadly distributed on chromosomes in gap 1 (G1) but become localized after DNA replication to the centromeres and intergenic regions along chromosome arms in yeast (5, 7). Cohesins must be present during replication for cohesion to be established, and expression after DNA replication cannot promote cohesion (80). Thus, the redistribution of cohesins in yeast is believed to result from a replication-mediated establishment of cohesion (79). Further, many replication fork components in yeast affect sister-chromatid cohesion, which supports a direct link between the replication fork and the establishment of cohesion. In S. pombe, temperature-sensitive (Ts) mutants of the replication initiator kinase Hsk1p and the DNA polymerase Eso1p (Polη/Ctf7) all have defects in sister-chromatid cohesion (61, 71). In S. cerevisiae, the replicative repair polymerase Trf4 (Polσ) and alternative replication factor C (RFC) complex (Ctf18, Ctf8, and Ddc1), as well as the Polα-interacting protein Ctf4, are both important for cohesion between sister chromatids (29, 59, 83). This subset of replication proteins that affects cohesion has led to the proposal that a specific replisome configuration is required to recruit cohesion complexes and establish sister-chromatid cohesion. This model posits that the processive polymerase (Polɛ) is replaced with a replicative repair polymerase, such as Polσ, for replication of topologically constrained regions of the genome (82). Polymerase switching is proposed to recruit the machinery required for the establishment of cohesion through a yet-to-be-described mechanism. One key part of this switch is the regulation of polymerase access to the primer-template junction; this could very well be a role for the alternative RFC complex (Ctf18, Ctf8, and Ddc1) and Ctf4.

CTF4 was identified in budding yeast by two distinct approaches: a genetic screen for mutants affecting chromosome transmission fidelity (CTF4/CHL15) and affinity chromatography with Polα to identify polymerase one binding proteins (POB1) (30, 41, 48). The stoichiometry of Ctf4-Polα coprecipitation from yeast extracts suggests that these polypeptides associate either weakly or transiently in vivo. Deletion of CTF4 from the budding yeast genome improves the recovery of an essential chromatin-remodeling complex, Cdc68/Pob3p, by Polα affinity chromatography, suggesting that Ctf4 inhibits Cdc68/Pob3p heterodimer binding to Polα. This result has been interpreted to suggest that CTF4 may regulate the assembly of Polα complexes (84). Although CTF4 is not an essential gene for vegetative growth in S. cerevisiae, loss of its function is lethal in combination with many mutations in DNA replication components, such as ctf18Δ. This loss also leads to hypersensitivity to methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), suggesting that Ctf4p is important for tolerating replication or genotoxic stress (22). Like most replication mutants, ctf4 delays cell cycle progression, while cells have large buds with 2N DNA content, and the nucleus is positioned in the bud neck (36). ctf4Δ viability is also adversely affected by the DNA damage checkpoint kinase mutant mec1-1 (48). Surprisingly, the ctf4 cell cycle delay is alleviated by the deletion of MAD2, a spindle assembly checkpoint component, suggesting that this delay arises in mitosis primarily from a defect in cohesion (29). However, the importance of a mitotic delay for ctf4 survival has not been reported.

For this study, we generated S. pombe mutants that showed an increased frequency of minichromosome loss (mcl). These were screened for two additional phenotypes: a mitotic cytology indicative of aberrant chromosome segregation and a requirement for the spindle assembly checkpoint to retain viability. Using these criteria, we recovered one Ts mutant, mcl1-1, that also displayed defective centromeric cohesion. Complementation of the mutant phenotypes identified a single suppressing gene, mcl1+, which showed significant sequence similarity to a family of eukaryotic proteins that includes Ctf4p, sepB, and AND-1 from Xenopus sp. and humans. The mcl1-1 mutant has a phenotype mutants, similar to those of sepB3 and ctf4Δ, such as defects in DNA metabolism and cell cycle progression. Our results also suggest the Mcl1p acts in DNA replication as a regulator of postreplication initiation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S. pombe strains and methods.

The strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells were grown in yeast extract with supplements (YES) or in Edinburgh minimal medium supplemented with the appropriate nutrients (49). Genetic interactions were assessed through standard mating techniques at permissive temperatures, followed by tetrad dissection on YES plates. Transformations were done by lithium acetate or electroporation methods (20, 34). Plasmid-based expression of epitope-tagged proteins was under the control of the nmt1 promoter in the pREP series of vectors; its expression was repressed with 5 μM thiamine (16).

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| SBP32590 | h+ ade6.704 leu1-32 ura4-294/pSP (CEN1-7L) ura4+ sup3-5 | L. Clarke |

| 544 | h− ade6.704 leu1-32 ura4-294/pSP (CEN1-7L) ura4+ sup3-5 | This study |

| 545 | h− mcl1-1 ade6.704 leu1-32 ura4-294/pSP (CEN1-7L) ura4+ sup3-5 | This study |

| 546 | h− mcl1-1 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 99 | h− ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | |

| 100 | h+ ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | |

| 53 | h− cdc10-129 leu1-32 | |

| 59 | h− wee1-50 leu1-32 | |

| 150 | h− cdc25-22 leu1-32 | |

| 246 | h− cut12-1 ade6-M216 his3-D1 leu1-32 | P. Nurse |

| 494 | h+ his7+:lacI-GFP lys1+:lacO leu1-32 ura4-D18 | M. Yanagida |

| 547 | h− mad2Δ::ura4+ ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. Sazar |

| 549 | h− bub1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | J. P. Javarzet |

| 1395 | h− rad26-T12 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | A. Carr |

| 1123 | h− rad26Δ::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | A. Carr |

| FY369 | h− cdc24-M38 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. L. Forsburg |

| FY421 | h+ chk1Δ::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. L. Forsburg |

| FY865 | h− cds1Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. L. Forsburg |

| FY945 | h− hsk1-1312 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. L. Forsburg |

| FY1105 | h+ rad3Δ::ura4+ ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | S. L. Forsburg |

| Sp358 | h− rqh1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | G. Freyer |

| Sz123 | h− rqh1-K547I ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | G. Freyer |

| NA74 | h− rad18-74 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | M. J. O'Connell |

| 550 | h+/h− mcl1Δ::ura4+/mcl1+ ade6-M210/M216 leu1-32 his3-D1 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 551 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 552 | h− mlm1-GFP::ura4+ rad21-K1::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 553 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cds1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 554 | h+ mcl1-GFP::ura4+ nmt1::GSTcds1 LEU2 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 555 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ hsk1-1312 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 556 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cdc21-M68 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 557 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ orp1-4 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 558 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cdc22-M45 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 559 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cdc17-K42 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 560 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cdc25-22 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 561 | h− mcl1-GFP::ura4+ cdc10-129 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 his3-D1 | This study |

| 563 | h− mcl1-1 cds1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 564 | h− mcl1-1 chk1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 566 | h− mcl1-1 cds1Δ::ura4+ chk1Δ::ura4+ ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 570 | h− mcl1-1 rad26-T12 ade6-M216 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 572 | h− mcl1-1 rad18-74 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D1 | This study |

| 573 | h− mcl1-1 rad9Δ::ura4+ ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 574 | h− mcl1-1 rad1Δ::ura4+ his3-D1 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 576 | h− mcl1-1 bub1Δ::ura4+ leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 577 | h− mcl1-1 rad26-T12 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 578 | h− mcl1-1 cdc10-129 leu1-32 | This study |

| 579 | h− mcl1-1 wee1-50 leu1-32 | This study |

| 580 | h− mcl1-1 cut4-533 | This study |

| 581 | h− mcl1-1 cut9-665 | This study |

| 582 | h− mcl1-1 cut1 | This study |

| 583 | h− mcl1-1 cut2 | This study |

| 584 | h− mcl1-1 cdc25-22 leu1-32 | This study |

| 585 | h− mcl1-1 cdc17-K42 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 586 | h+ mcl1-1 pol1-1 ade6-704 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 587 | h− mcl1-1 orp1-4 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 588 | h− mcl1-1 cdc22-M45 ade6-M210 leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

| 594 | h+ mcl1-1 his7+:lac1-GFP lys1+:lacO leu1-32 ura4-D18 | This study |

Screening for minichromosome loss mutants.

Ten independent SBP32590 cultures were treated with 2% ethyl methanesulfonate until 20% viable, washed extensively in 50% sodium thiosulfate, and then plated onto Edinburgh minimal medium supplemented with uracil, leucine, and low adenine (10 μg/ml). A total of 60,000 cells were screened for red-white colony sectoring, which is indicative of minichromosome loss (28a). A total of 256 sectoring mutants were backcrossed three times to strains SBP32590 and 544 (Table 1), resulting in 40 consistently sectoring mutants.

Light microscopy.

Cells fixed with 4% formaldehyde-0.2% glutaraldehyde were characterized by using standard procedures for immunofluorescence (28). Microtubules (MTs) were stained with the 4A1 antibody (54), septal material was stained with Calcofluor (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), and DNA was stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Lagging chromosome and cells untimely torn (Cut) phenotypes were scored as defects in chromosome segregation (57). Live cells were prepared for green fluorescent protein (GFP) fluorescence by suspension in alkaline YES, pH 7.5 (to facilitate chromatin staining with 1 μg of Hoechst 33342 stain/ml), and attached to coverslips coated with isolectin B from Griffonia simplifolia (Sigma) and then imaged with a Zeiss Axioplan 2 by using the Slidebook software package (Intelligent Imaging Inc., Denver, Colo.). Eight images at 0.5-μm focal steps were acquired to encompass the entire nuclear volume. Z-series image stacks were deconvolved with a nearest-neighbor algorithm. These sharpened images were analyzed for sister-chromatid separation by stepping through the entire nuclear volume. This allowed us to assess the distance between GFP spots with the ruler function of this software package. All deconvolved images presented here are two-dimensional projections of Z-series images deconvolved with a no-neighbor algorithm. For live cell imaging, log-phase cultures of mutant strains were transformed with pDQ105 (which expresses α-tubulin-GFP) (18), stained with Hoechst 33342 and Calcofluor in YES (pH 7.4), and imaged by fluorescence microscopy on YES agar pads. Mitotic cells were identified by spindle formation, apparent as a short bar of MT fluorescence visible in the fluorescein isothiocyanate channel.

Cloning of mcl1+.

A his3+ genomic library (51) was transformed into the mcl1-1 mutant by electroporation, and cells were screened for rescue of their Ts phenotype. Isolated plasmids competent to rerescue both the Ts and minichromosome loss phenotypes were sequenced. Only a single open reading frame (ORF), contained in two independently isolated plasmids, was found to fully suppress the mcl1-1 phenotypes after sixfold genomic coverage of the library. To confirm this sequence-represented mcl1+ gene, we generated epitope-tagged alleles of this DNA (see below), integrated these into the genome, and demonstrated their tight linkage to the mcl1-1 phenotype.

Construction of null and epitope-tagged alleles of mcl1+.

The 2,548-bp ORF of mcl1+ (GenBank accession number AL590605) was replaced by homologous recombination with a linear DNA containing the ura4+ gene flanked by a 1.2-kbp XbaI-SpeI 5′ genomic fragment and a 900-bp 3′ BsgI genomic fragment. Transformations were done in freshly made diploid cells. Diploid uracil prototrophs were screened by PCR, and all clones determined to be positive for integration by PCR were confirmed by Southern blot analysis of NcoI- and SphI-restricted genomic DNA.

Mcl1p was epitope tagged by PCR amplification of the mcl1+ ORF with the following primers: 5′ ACGCGTCGACTATGGCAGGGAATAGGCTAGTTCCTAGA and 5′ GAAGATCTCAGGTTAGATAGTAGATTACCAATTTTTTCA for C-terminal tags or 5′ GAAGATCTTTACAGGTTAGTATAGTAGATTACCAATTTTTCA for N-terminal tags. Gel-purified PCR products were cloned first into pCR4Topo (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and then sequenced. A SalI-BglII fragment was then cloned in frame with the epitopes in the pREP series of vectors (16). To epitope tag the mcl1+ genomic locus, an XbaI-SphI fragment from the pREP vectors, containing 1,500 bp of the mcl1+ ORF and the epitope tag, was excised and used to replace the 5′ XbaI-SpeI fragment in the vector used to make the null allele. Integration was performed and confirmed as described above.

Flow cytometry.

For the flow-cytometric quantification of DNA, 1-ml samples taken from cultures at the time points indicated were washed twice in sterile distilled H2O. Cells were prepared for flow cytometry (fluorescence-activated cell sorter [FACS]) as described in reference 1 by using propidium iodide to stain the nucleic acids.

Treatments with TBZ, HU, UV, γ-ray, and MMS.

Cells in liquid cultures containing 12 mM HU or 100 μg of thiabendazole (TBZ)/ml were arrested for <3 h at the specified temperatures unless otherwise indicated. Sensitivities to HU and MMS were assayed by using cells in early log phase (A595 = 0.3 to 0.6). To assess viability, cells were washed, diluted 1/10,000, and plated to determine the number of viable CFU as a function of increasing exposure. In plating assays, serial dilutions from 106 to 320 cells/ml for each culture were applied to a set of YES control plates or a set of plates containing YES plus either TBZ (5, 10, 12.5, and 20 μg/ml), HU (1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mM), or MMS (0.005 and 0.0025%). Plates were incubated for 4 days at 25°C.

For γ-irradiation, 1.5-ml liquid YES cultures were placed in a rotating cylinder and exposed to a 137Cs source emitting 3.7 Gy/min. Samples were taken every hour for 5 h, during which 1,110 Gy was emitted. Viability was determined as described above by counting CFU as a function of irradiation. UV sensitivity was measured by plating early-log-phase cells diluted to 1,000 cells/ml in YES onto YES agar. Plates were allowed to dry and then exposed to appropriate amounts of UV in a Pharmacia Stratalinker (Peapack, N.J.) equipped with a photodiode detector.

Chromatin binding assays were performed as described by Kearsey et al. (38). Cdc mutants carrying mcl1-GFP::ura4+ were synchronized for chromatin extraction by shifting the cultures to 36°C for 3 h.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was performed as described by Birkenbihl and Subramani (6), except the gel-running conditions were 2 V/cm at an angle of 106°, switching polarity every 1,800 s for 83 h in 0.5× Tris-acetate-EDTA at 16°C, exchanging the buffer every 24 h. After electrophoresis, chromosomes were stained with ethidium bromide and visualized with UV B.

Kinase assays.

Protein lysates were prepared by glass bead bashing. Immunoprecipitations were carried out with 16B12 monoclonal antibodies (Babco, Berkeley, Calif.), and immunoglobulin G complexes were precipitated with Pansorbin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.). Phosphatase inhibitors (50 mM sodium fluoride, 50 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 20 μM sodium vanadate) were included in initial washes but were removed prior to kinase assays. Kinase assays were performed as described previously (61), except that GST-Wee1p (1 to 70 amino acids [aa]) was used as the kinase substrate (8).

RESULTS

Screening of mcl mutants identified mcl1-1.

mcl1-1 was recovered in the screening of 60,000 ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized cells by looking for increased rates of minichromosome loss by a colony-sectoring assay at 25°C. This screening produced 40 consistently sectoring mutants (see Materials and Methods) that we further screened for unequal chromosome segregation by fluorescence microscopy. Fifteen such mutants were tested for genetic interactions with the spindle assembly checkpoint mutant bub1Δ. This stringent screening recovered only one mutant, mcl1-1, which grew slowly at 25°C and was restricted for growth at 36°C.

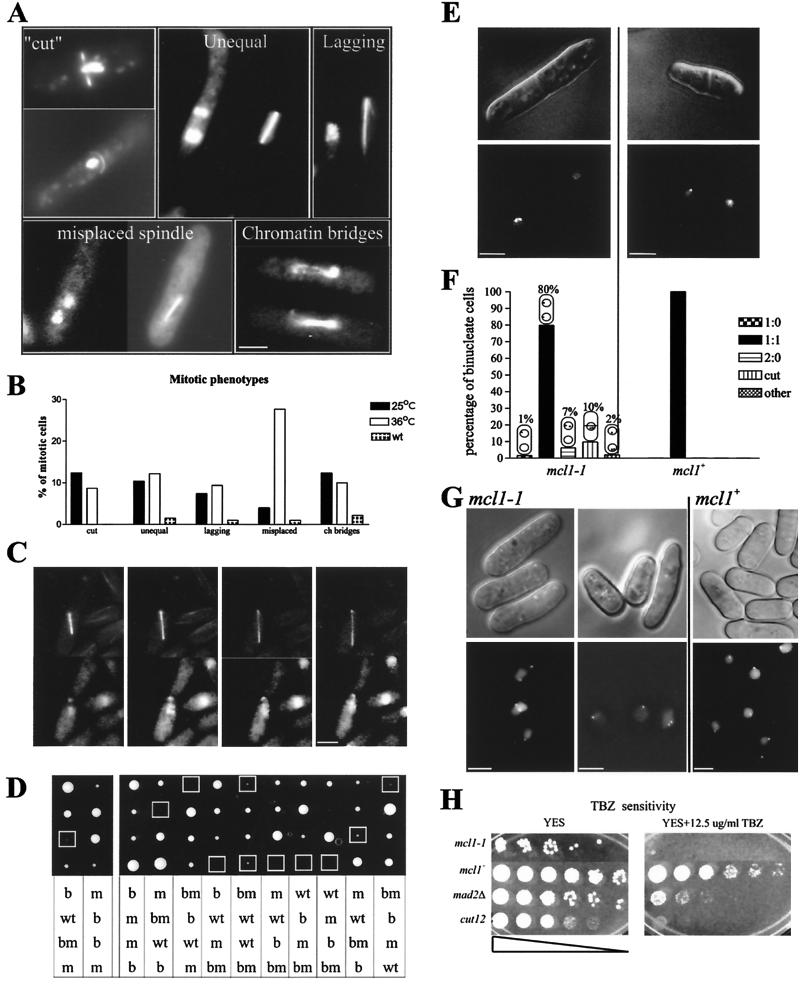

Fixed mcl1-1 cells examined by fluorescence microscopy showed five categories of aberrant mitotic phenotypes: septation prior to chromatin segregation (Cut) (1), an unequal assortment of DNA to daughter cells (2), lagging chromosomes (3), asymmetric spindle placement within the cell (4), and chromatin bridges (5) (Fig. 1A). The percentage of mitoses with these phenotypes is presented graphically in Fig. 1B. The mitotic index of mcl1-1 cells grown at 25°C was not significantly different from a parental control strain's mitotic index at 25°C (8.6% compared to 8.1%, respectively). However, the mitotic index of mcl1-1 cells decreased to 4.3% after 8 h at 36°C while that of control strains remained unchanged. This result suggests that mcl1-1 cells have a premitotic arrest of the cell cycle at the restrictive temperature.

FIG. 1.

mcl1-1 shows defects in chromosome segregation and cohesion. (A and B) Mitotic phenotypes are identified in log-phase cultures of strains SPB32590 (wild type [wt]) and 545 (mcl1-1) fixed at permissive temperature (25°C) or of strain 545 grown for 8 h at the restrictive temperature (36°C). Panel A is a gallery of representative images for the five categories of mitotic phenotypes presented graphically in panel B. ch, chromatin. (C) mcl1-1 cells expressing α-tubulin-GFP were grown on YES agar pads. The top row of images shows GFP fluorescence, and the bottom row shows chromatin stained with Hoecsht 33342. Images represent an elapsed time of 30 min. Bar, ∼3 μm. (D) Twelve tetrads from mcl1-1ts (strain 546) cross with bub1Δ::ura4+ (strain 549), photographed after 4 days of growth on YES agar at 25°C. Genotypes were determined by replica plating and are given as follows: wt, mcl1+ bub1+; b, bub1Δ::ura4 mcl1+; m, mcl1-1ts bub1+; bm, bub1Δ::ura4 mcl1-1ts). (E, F, and G) Differential interference contrast (top panels) and deconvolution microscopy with fluorescence optics (lower panels) were used to image living mcl1-1 (strain 594) and mcl1+ (strain 494) cells with a marked centromere, centromere I. (E) Binucleate cells show 2:0 and 1:1 segregation. (F) Segregation patterns were categorized as follows: one GFP spot in only one nucleus of two (1:0), one GFP spot in both nuclei (1:1), two GFP spots in only one nucleus of two (2:0), no segregation (cut), or more than two GFP spots present (other). (G) Representative images from the sister-chromatid cohesion study are shown. (H) Serial dilutions of mcl1-1 (strain 546), mcl1+ (strain 100), mad2Δ (strain 547), and cut12-1 (strain 246) plated onto YES agar and YES agar plus 12.5 μg of TBZ/ml. Bars, 5 μm.

These five categories of mitotic phenotypes could represent pleiotropy or gradations of a chromosome loss phenotype. We used live cell observations to distinguish between these possibilities by determining patterns of progression for the static phenotypes observed in the fixed material. Forty living mcl1-1 cells were characterized during mitosis by fluorescence microscopy for 30 min or until telophase. Fourteen of the 40 carried out aberrant mitoses that exhibited multiple abnormal phenotypes. These mitoses contained chromatin bridges that commonly progressed to lagging chromosomes. Typically, these cells stopped mitotic progression with mitotic spindles that looked misplaced within the cell (Fig. 1C), and all the cells with lagging chromosomes remained arrested with an elongated spindle for the duration of the observation, suggesting a mitotic checkpoint arrest (25).

The third stage of the screen revealed that mcl1-1 shows synthetic interactions with the spindle assembly checkpoint mutant bub1Δ. Tetrads dissected from crosses between these two mutants generated microcolonies that were determined to be double mutants (Fig. 1D); only two double-mutant colonies propagated beyond initial colony formation. These strains had a 10-fold decrease in viability compared to that for mcl1-1 cells, as determined by the plating efficiency at 25°C (data not shown). To better understand the importance of the spindle assembly checkpoint pathway, we assessed genetic interactions with the known downstream targets of the spindle assembly checkpoint (Table 2) and found interactions only with the cohesin mutant rad21-K1, which was synthetically lethal with mcl1-1.

TABLE 2.

Genetic interactions

| Mutant | Function | Interaction |

|---|---|---|

| Spindle checkpoint | ||

| mad2Δ | Checkpoint component | Slight interaction |

| bub1Δ | Checkpoint kinase | Loss of viability upon passage |

| cut4 | Anaphase-promoting complex | No interaction |

| cut9 | Anaphase-promoting complex | No interaction |

| cut2 | Securin | No interaction |

| cut1 | Separin (protease) | No interaction |

| rad21-K1 | Cohesin | Symthetic lethality |

| DNA damage checkpoint | ||

| rad3Δ | Checkpoint kinase | Synthetic lethality |

| rad26Δ | Checkpoint component | Synthetic lethality |

| rad26-T12 | Checkpoint component | No interaction |

| rad1Δ | PCNA-like checkpoint protein | Decreased permissive tempa |

| rad9Δ | PCNA-like checkpoint protein | Decreased permissive tempa |

| rad18-74 | Recombination SMC | Decreased permissive tempa |

| cds1Δ | Replication checkpoint kinase | Partial rescue |

| chk1Δ | G2 checkpoint kinase | No interaction |

| mik1Δ | cdc2-inhibiting kinase | Decreased permissive temp |

| wee1-50 | cdc2-inhibiting kinase | Decreased permissive temp |

| cdc25-22 | cdc2-activating phosphatase | cdc phenotype at permissive temp |

| Replication components | ||

| pol1-1 | α-Polymerase | Decreased permissive tempa |

| orp1-4 | Origin recognition component | No interaction |

| cdc17-K42 | DNA ligase | No interaction |

| cdc22-M45 | Ribonucleotide reductase | Decreased permissive tempa |

| cdc21-M68 | MCM4 (DNA helicase subunit) | No interaction |

| hsk1-1312 | DNA replication initiation | Synthetic lethality |

| rad12-Δ | RecQ homologue | Synthetic lethality |

| rad12-KI | RecQ helicase dead mutant | Synthetic lethality |

| cdc24-M38 | Essential replication component | Synthetic lethality |

| dna2+ | Helicase/exonuclease | OP partial rescueb |

Decreased maximum permissive temperature of mcl1-1 by 3°C.

dna2+ overproduction (OP) in mcl1-1 cells rescued MMS sensitivity and increased maximum permissive temperature by 3°C.

mcl1-1 cells missegregate endogenous chromosomes due to a defect in sister-chromatid cohesion.

The extent and nature of endogenous chromosome loss were measured by studying mcl1-1 and mcl1+ strains carrying a tandem array of lac operator (lacO) repeats integrated at the lys1+ locus and also expressing a lacI-GFP chimera that binds to the lacO repeats. This construct acts as a visual marker for the centromere-proximal region of chromosome I (74). A single spot of GFP fluorescence is visible in wild-type cells during interphase; this separates into two during mitosis. We scored chromosome segregation patterns in postmitotic cells prior to cytokinesis so that we could see both daughter nuclei in a single cell. In log-phase cultures at 25°C, 1.5% of the 200 binucleate mcl1-1 cells observed showed a 1:0 segregation of the GFP-marked chromosome, suggesting either chromosome loss or nondisjunction. A quantity of 6.2% showed a 2:0 segregation, suggesting sister-chromatid separation without segregation. There were 9.8% that had a Cut phenotype with separated sister chromatids, and 2% had more than two centromeric GFP spots. In an equal number of isogenic mcl1+ binucleate cells, no missegregation event was observed (Fig. 1E and F).

The 2:0 and Cut-chromosome segregation patterns, as well as synthetic lethality with the cohesin mutant rad21-K1, suggested that sister chromatids were separating prematurely, leading to failed mitoses. Therefore, we examined preanaphase cohesion in cen1-GFP-marked strains. Cultures at 25°C were treated with 12 mM HU in late S phase and then released into 100 μg of TBZ/ml for 1 h to block mitotic entry. A total of 96.5% of the mcl1+ cells contained a single GFP spot, and 3.5% had two GFP spots separated by ∼1 μm by fluorescence microscopy (n = 1,588). In contrast, 14.9% of the mcl1-1 cells contained two GFP spots per nucleus separated by an average distance of ∼2 μm (n = 1,122). Representative images are presented in Fig. 1G.

The decreased cohesion seen in mcl1-1 cells should promote an increased sensitivity to TBZ, since sister-chromatid separation will be exacerbated by TBZ arrest and should be fatal upon return of the mitotic spindle, as is found in rad21-K1 cells (73). mcl1-1 cells were unable to grow in 12.5 μg of TBZ/ml (Fig. 1H). This sensitivity is similar to that found in the spindle pole body mutant cut12-1 and greater than that found in the spindle checkpoint mutant mad2Δ (11, 32).

Mcl1p is a member of a conserved protein family.

Only two genomic plasmids were recovered through our complementation analysis; both contained the same 2,548-bp ORF (SPAPB1E7.02c; accession number AL590605). Northern blot analysis confirmed that a corresponding ∼2.8-kbp message was present in equivalent amounts throughout the cell cycle (data not shown). We integrated ura4+ 1.5 kb 3′ of the ORF and demonstrated linkage between this locus and the mcl1-1 mutant's Ts phenotype in both tetrad and random spore analysis. We sequenced the mcl1-1 mutant locus and found a single mutation, a guanine-to-adenine transition, 372 nucleotides into the ORF. This changes a TGG (Tyr) to TGA (stop), which prematurely terminates translation after 124 aa.

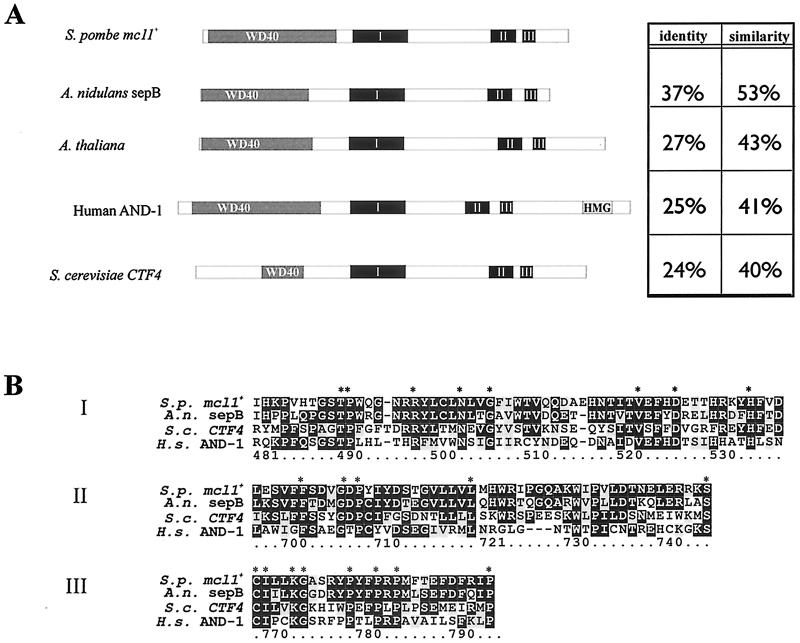

mcl1+ encodes an 815-aa, highly acidic (pI 4.9), 90.9-kDa protein with similarity to the previously described fungal genes sepB from Aspergillus nidulans and CTF4 from S. cerevisiae (30, 41, 48). Highly similar proteins were also detected by BLAST searches (3) in Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Arabadopsis thaliana, Neurospora crassus, Xenopus laevis, and humans (AND-1), suggesting a conserved eukaryotic family of proteins. Protein domain analysis of Mcl1p by using Pfam identified five β-transducin—also known as WD40 repeat—domains at the N terminus, a motif common to all members of this putative protein family (Fig. 2A) (62). Clustal X alignment of putative family members revealed three highly conserved domains that we refer to here as the sepB boxes. These domains appear in a consistent order across the phyla and are unique to this family of proteins, distinguishing it from the plethora of other β-transducin or WD40 proteins (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

mcl1+ is a member of a eukaryotic protein family. (A) The domain structure of Mcl1p and sequence comparison results among a select set of sepB family members are shown. Identity and similarity percentages are for comparisons over the entire length of the protein by using the Smith-Waterman algorithm (60). HMG, high-mobility group. (B) Clustal W alignment of the CTF4- and sepB-like proteins reveals three domains of high similarity in these aligned peptide sequences (2). S.p., S. pombe; A.n., A. nidulans; S.c., S. cerevisiae; H.s., Homo sapiens.

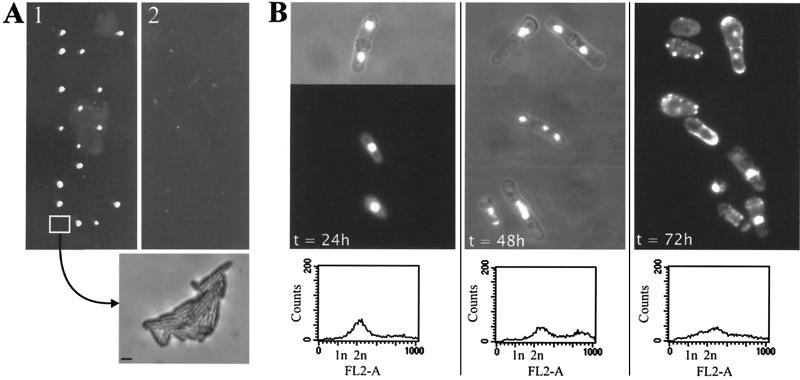

mcl1+ is an essential gene.

The premature termination of the mcl1-1 allele would be predicted to create a null allele, suggesting that mcl1+, like CTF4, is not essential. We determined the null phenotype by replacing mcl1+ with the ura4+ gene to generate mcl1Δ::ura4+ mcl1+ diploids (see Materials and Methods). When these strains were sporulated and tetrads were dissected onto complete medium, no more than two of the four spores formed colonies after a week of growth (Fig. 3A, panel 1). Replica plating to medium lacking uracil confirmed that none of the colonies contained the mcl1Δ::ura4+ null allele (Fig. 3A, panel 2). Examination of the presumptive mcl1Δ spores under a dissection microscope revealed that the null spores had germinated but grown extremely slowly, forming microcolonies of long, cdc-like cells after a week of growth (Fig. 3A, bottom image).

FIG. 3.

mcl1+ is an essential gene. (A) Tetrads dissected from sporulated heterozygous diploids result in two colonies and two microcolonies (panel 1, with tetrads placed horizontally). Replica plating to medium selective for uracil prototrophy demonstrated that none of the visible colonies carried the gene replacement (panel 2). Null cells generated a microcolony on YES agar and are shown in the image below panel 2 (bar, ∼20 μm). (B) Null spores were selectively germinated in medium lacking uracil. Cells were stained with DAPI and Calcofluor. The three panels show representative fields of cells from the selectively germinated mcl1Δ culture at t = 24, 48, and 72 h, with histogram plots from FACS below each panel.

The mcl1Δ phenotype was further characterized by selective germination in medium lacking uracil. Microscopic examination of fixed, DAPI-stained mcl1Δ cells after 48 h revealed that most cells became Cut and had stretched chromatin or lagging chromosomes similar to those found in the mcl1-1 mutant (Fig. 3B). By 72 h, half the cells in the culture had no visible DAPI-stained nuclear material. Flow cytometry showed that mcl1Δ cells germinated and went from 1N to 2N, with kinetics similar to those of the wild-type cells, but they progressively became aneuploid by 48- and 72-h growth (Fig. 3B, bottom panels). These data suggest that the mcl1-1 allele is not equivalent to a null mutation but must retain some residual function, either in the truncated protein product or as a result of a low level of translational read-through of the premature stop.

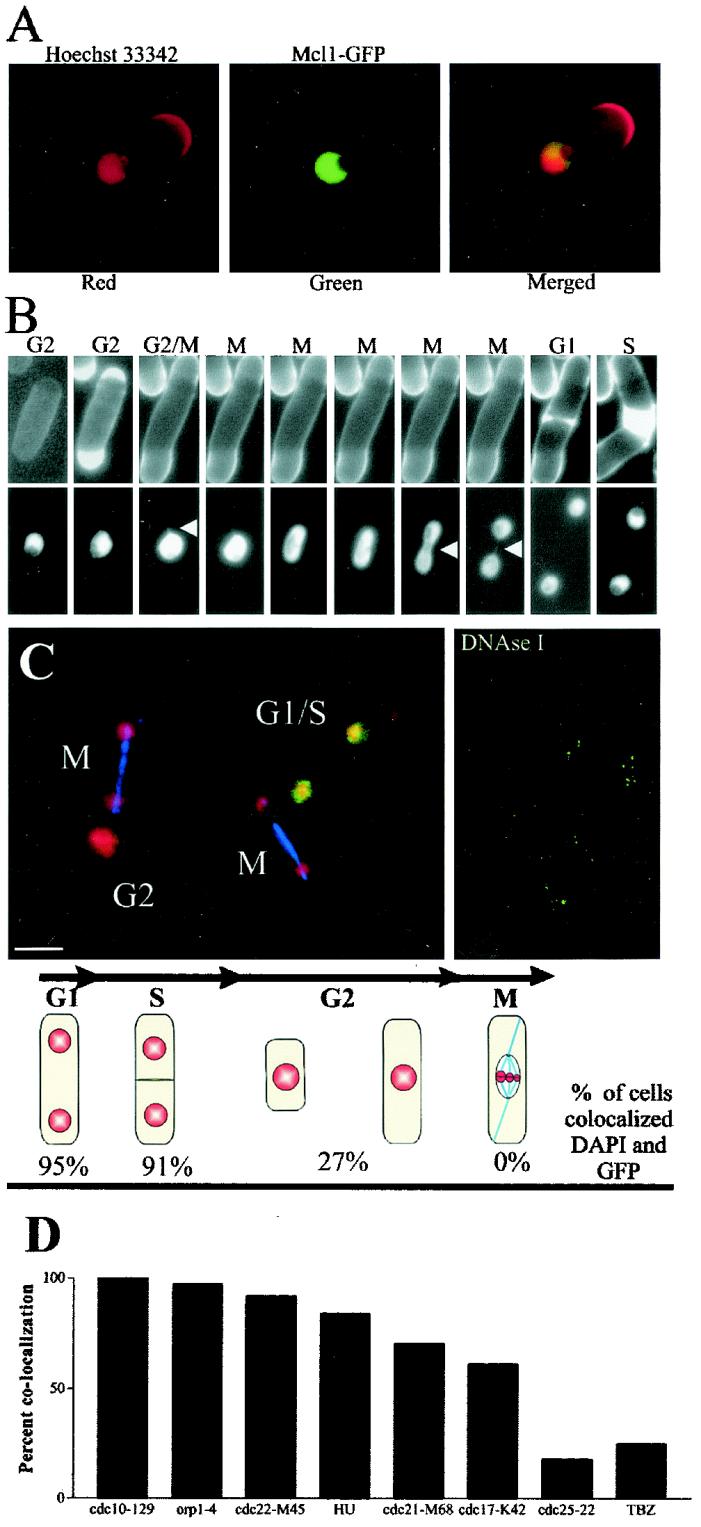

Mcl1-GFP is a constitutive nuclear protein that associates with chromatin from G1 to S phase. In S. cerevisiae, Ctf4p interacts with Polα and is present in a constant amount throughout the cell cycle and it associates with chromatin from the S to M phases of the cell cycle (29). To determine if Mcl1p localizes similarly, we used a mcl1-GFP chimera expressed from the endogenous mcl1+ promoter. Mcl1-GFP strains were wild type for all mcl1-1 phenotypes and showed constitutive nuclear localization. GFP fluorescence appeared excluded from at least part of the nucleolus, based on the absence of fluorescence from the region occupied by the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) bars that protrude from the bulk of the chromatin in fission yeast (Fig. 4 [the red crescent is Hoechst staining of recently deposited cell wall material]) Live cells expressing the chimera showed no variation in protein localization throughout the cell cycle, but a large fraction of Mcl1-GFP appeared to be freely diffusible within the nucleus as it filled any deformation of the nuclear envelope (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Mcl1-GFP is a constitutive nuclear protein that associates with chromatin during G1 and S phase but not during mitosis. (A) Hoechst 33342-stained DNA forms a three-quarters circle with two protruding bars, which are the rDNA genes extending into the nucleolus. Mcl1-GFP expressed from its endogenous promoter fills the nuclear volume but appears excluded from one region. Merged images show that exclusion is coincident with the rDNA and nucleolus. (B) Live cell fluorescence microscopy of cells stained with Calcofluor (top panels) and GFP fluorescence (bottom panels). There was no apparent redistribution of Mcl1-GFP fluorescence through the cell cycle, and any deformation in the nuclear membrane was filled with GFP fluorescence (white arrowheads), indicating that much of the Mcl1-GFP is freely diffusible in the nucleus. (C) Log-phase cells showing MTs in blue, DNA in red, and Mcl1-GFP in green. Using cell morphology to assess the cell cycle stage, we quantified the fraction of cells in which GFP and DNA colocalized after the extraction of soluble protein (see Materials and Methods). The data are presented just below the panel of images (n = 251). The far right panel is an image of cells treated with DNase I and then similarly extracted. The bar represents 5 μm. (D) Chemical and mutant cell cycle arrests were used to confirm log-phase results for the stage-specific localization of Mcl1-GFP to chromatin. We tested the retention of Mcl1-GFP in cdc10-129 (strain 561), orp1-4 (strain 557), cdc22-M45 (strain 558), HU (strain 551), cdc21-M68 (strain 556), cdc17-K42 (strain 559), cdc25-22 (strain 560), and TBZ mutants (strain 551) under arrested conditions (3 h at 36°C for mutants and 3 h at 32°C for chemical arrests). The percentages of cells (n > 200 each) in which GFP signal colocalized with DAPI are presented graphically.

Soluble Mcl1-GFP was extracted from the nuclei of detergent-permeabilized cells to visualize any structure-bound material (see Materials and Methods). In log-phase cells, Mcl1-GFP colocalized with DAPI-stained DNA and retention of the GFP signal correlated with the stage in the cell cycle. Mcl1-GFP appeared structure bound and colocalized with chromatin predominately in binucleate G1/S cells, but it was washed from chromatin in cells with a single nucleus (G2) and was absent from all nuclei that contained a mitotic spindle (Fig. 4C). Nuclear retention of Mcl1-GFP was abolished by DNase I digestion of permeabilized cells, followed by the same extraction (Fig. 4C).

Since this result differs from the reported localization of Ctf4p, which is chromatin bound from S to M phase, we examined the relationship between cell cycle and Mcl1-GFP-DNA colocalization more closely. We constructed a series of mcl1-GFP cdc double-mutant strains (cdc10-129 [G1], orp1-4 [prereplication initiation], cdc22-M45 [early S phase], cdc21-M68 [mid-S phase], cdc17-K42 [late S phase], and cdc25-22 [G2]) and used HU (S phase) or TBZ (pre-M phase) to enrich for cells at specific cell cycle stages prior to chromatin extraction. These arrested cells showed a gradual loss of Mcl1-GFP from chromatin as the G1/S phase (100% in cdc10-129 mutant) gave way to G2 (18% in cdc25-22 mutant) (Fig. 3D). Indeed, 25% of the cells in Mcl1-GFP cultures treated for 3 h with 100 μg of TBZ/ml exhibited GFP-DAPI colocalization, but of this 25%, a significant number had two nuclei (89%), indicating a partial escape from the TBZ arrest during preparation.

Genetic interactions and synthetic dosage effects indicate that mcl1+ affects DNA replication.

CTF4 mutants interact with a number of replication components, so we also looked for genetic interactions between mcl1-1 and various replication mutants (Table 2). Similar to ctf4Δ, we found only moderate interactions between the pol1-1 mutant and mcl1-1. The severest phenotypes were found between mcl1-1 and the DNA replication initiator kinase mutant hsk1-1312, two alleles of the RecQ helicase (rqh1Δ, rqh1-K547I), and an allele of the essential DNA replication factor cdc24-M38, which interacts with PCNA and RFC (17, 26, 61). Additionally, we found that multicopy genomic plasmid containing dna2+ gave partial rescue of mcl1-1's phenotypes (26, 69). We found no interactions with cdc21-M68, orp1-1, or cdc17-K42.

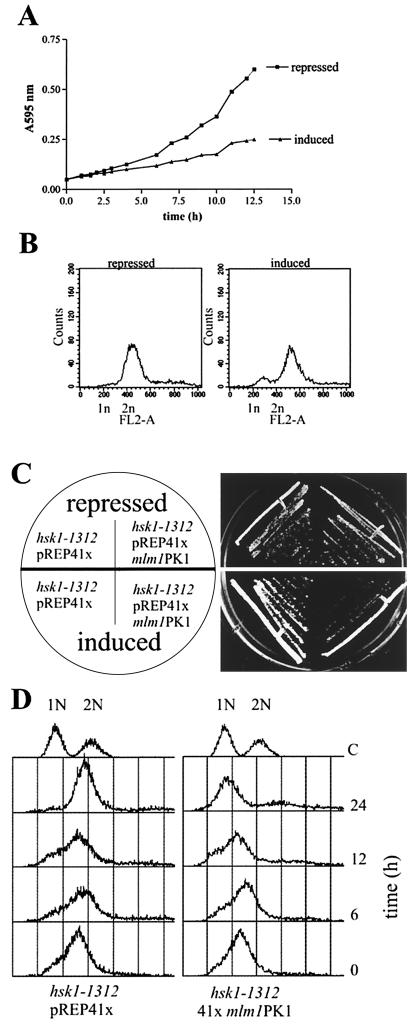

mcl1+ expression from either pREP3X or multicopy genomic plasmids caused wild-type cells to grow more slowly than under plasmid-repressed or plasmid control conditions. Overexpression of mcl1+ led to cdc-like cells that were biased toward <2N DNA content (Fig. 5A and B). S. pombe cells rarely show a 1N DNA content by FACS because cytokinesis is not completed until mid-S phase, making cells appear to have a 2N DNA content throughout the cell cycle. If overexpression of mcl1+ indeed causes a DNA replication delay relative to septation, we reasoned that replication mutants that interact with or regulate Mcl1p function or DNA replication might be acutely sensitive to Mcl1p overexpression. Thus, we looked for synthetic dosage phenotypes in replication mutants when Mcl1-PKp was expressed from a medium-strength promoter (pREP41x), a level of expression that causes no detectable phenotypes in wild-type cells. Of the mutants listed in Table 2, only the hsk1-1312 mutant showed synthetic dosage interactions. Viability of hsk1-1312 was not affected by Mcl1-PKp overproduction at 29°C, since both of these strains had a similar plating efficiency (Fig. 4C). However, the hsk1-1312 strain overproducing Mcl1-PKp grew slower and formed only microcolonies in the time sufficient for hsk1-1312 strains carrying empty vectors to form normal-sized colonies. Flow cytometry performed on these two strains grown at 29°C in liquid culture indicated that they contained a similar DNA content until 12 h of induction, when maximal production of Mcl1-PKp was reached (23). By 24 h, excess Mcl1-PKp caused a <2N DNA bias in the population of hsk1-1312 cells whereas the empty vector controls appeared normal with a 2N DNA content (Fig. 5D). Thus, it appears that overproduction of Mcl1p exacerbates the S-phase delay phenotype of hsk1-1312 cells at 29°C (61, 68).

FIG. 5.

Overexpression of Mcl1p causes a G1/S arrest. (A) Wild-type cells (strain 100) transformed with pREP3x mcl1-GFP grow slowly when expression is induced. (B) FACS analysis of cells induced for 12 h show a modest G1 accumulation in cells expressing high levels of mcl1-GFP compared with cells repressed for this expression. (C) Expression of Mcl1-PK in the hsk1-1312 (FY594) mutant under inducing conditions severely retarded growth of the mutant in comparison to hsk1-1312 mutant carrying an empty vector. However, this expression does not lead to increased cell death. Cells were grown for 4 days at 29°C. (D) hsk1-1312 cells under inducing conditions for 24 h have a shift to 1N DNA content when expressing mcl1-PK but not in the empty vector controls (C). Expression from the nmt promoter starts at time zero and reaches a maximum after 12 h (23). Data are representative of three independent transformations of hsk1-1312 mutants with pREP41x mcl1-PK1 and pREP41x mcl1-GFP.

mcl1-1 affects chromosome integrity.

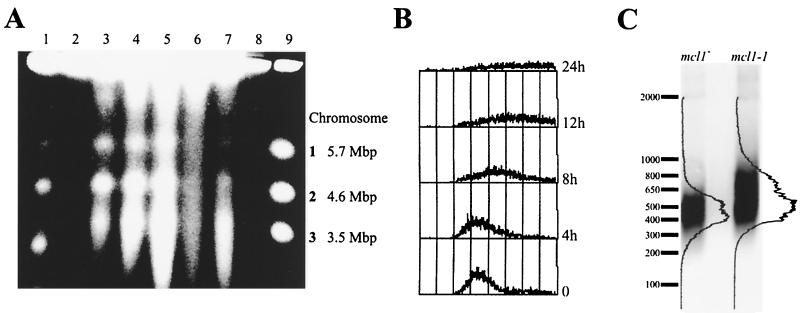

Chromatin bridges were common to mcl1-1 mitoses, suggesting incomplete DNA replication or poor resolution of sister chromatids. If chromosomes were incompletely replicated in mcl1-1, then their migration in PFGE gels should be severely retarded, as when wild-type cells are HU arrested (Fig. 6A, lane 2). However, the chromosome-banding pattern for the mcl1-1 chromosomes at 25°C appears not reduced but more diffuse than that of the mcl1+ control. This indicates that mcl1-1 chromosomes were heterogeneous in either size or structure (Fig. 6A, compare lane 3 with lanes 1 and 9). Since the mcl1-1 chromosome banding became more diffuse with time at the restrictive temperature of 36°C (Fig. 6A, lanes 4 through 6), we believe the marked loss of chromosome banding or migration into the gel matrix is consistent with the irreversibility of this temperature shift and the level of aneuploidy of mcl1-1 cultures, as measured by FACS (Fig. 6B).

FIG. 6.

mcl1-1 cells have an altered chromosome structure. (A) A total of 106 cells (2 μg of DNA) per lane were prepared for PFGE analysis from mcl1+ and mcl1-1 cultures. mcl1+ cells were incubated at 25°C (1) and arrested with 12 mM HU for 3 h (2). mcl1-1 cells were incubated at 25°C (3), and mcl1-1 cells were shifted to incubation at 36°C for 4 (4), 8 (5), and 12 h (6). mcl1-1 cells were arrested for 3 h in 12 mM HU (7). cdc24-M38 cells were shifted to 36°C for 3 h of incubation (8) and by the S. pombe chromosome standards (9). (B) FACS profiles of mcl1-1 held at 36°C for 0, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h are shown. (C) A Southern blot of ApaI-digested genomic DNA isolated from tetrad-matched mcl1+ and mcl1-1 strains and grown to 100 generations at 25°C is shown. The blot was probed with a 300-bp subtelomeric fragment that detects the 3′ terminus of the telomere (4).

The chromosomal heterogeneity found in mcl1-1 suggested complete replication, but at a fidelity that was sufficiently low that deletions, duplications, or nonhomologous recombination events were common. Telomeres are particularly affected by either heightened recombination or defective replication regulation (15, 19). Therefore, we examined telomere lengths in tetrad-matched mcl1+ and mcl1-1 cells grown to 100 generations at permissive temperatures. Isolated genomic DNA was digested with ApaI, separated on a 1.2% agarose gel, blotted, and probed with a 300-bp subtelomeric sequence (4). The mcl1-1 mutant showed a 100- to 300-bp increase in average telomere length compared to that in the mcl1+ mutant (Fig. 6C), suggesting that Mcl1p plays a role in regulating telomere replication. This has not been observed for the other members of this protein family.

Passage through mitosis at restrictive temperatures is lethal to mcl1-1.

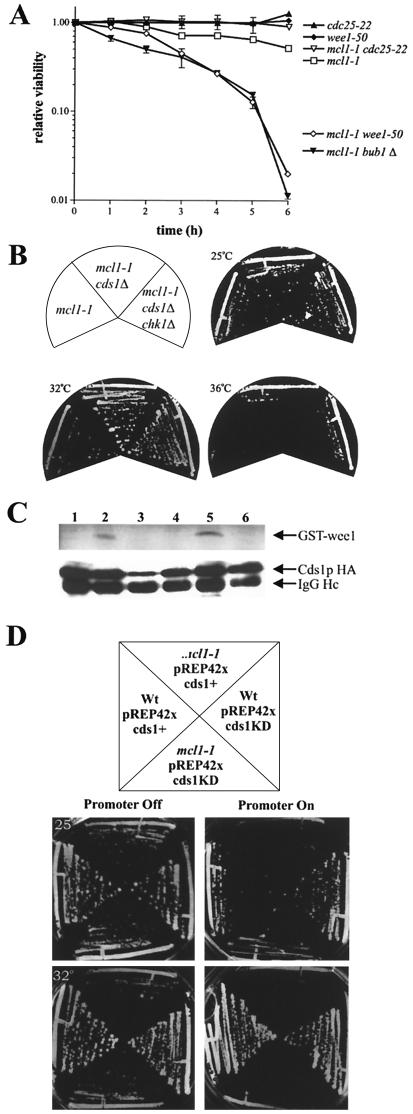

The A. nidulans sepB3 strain shows a delay of septation that is dependent on the Ataxia-telangiectasia-related DNA damage checkpoint kinase uvsB (31). In S. cerevisiae, the ctf4-s65 mutant's cell cycle delay is dependent on the spindle assembly checkpoint component Mad2p (29). We have found evidence for both G2 and mitotic delay in mcl1-1 mutant. Therefore, we wished to compare the relative contribution of the G2/M and spindle assembly checkpoints for mcl1-1 viability at the restrictive temperature. We constructed double mutants containing mcl1-1 and the Ts allele wee1-50 or cdc25-22 for comparison to the mcl1-1 bub1Δ mutant. At 36°C, wee1-50 drives cells into mitosis and cdc25-22 blocks mitotic entry (24). Double mutant strains with mcl1-1 were viable at 25°C, although mcl1-1 cdc25-22 double mutants grew significantly slower and looked cdc-like. Upon shifting to 36°C, the cdc25-22 mcl1-1 double mutant arrested in G2 prior to mitosis and, when returned to permissive temperature, maintained a higher relative viability than the mcl1-1 mutant alone. In contrast, the mcl1-1 wee1-50 and mlm1-1 bub1Δ double mutants dramatically lost relative viability after 4 h at the restrictive temperature (Fig. 7A). This loss of viability was not found for single mutants, suggesting that unrestricted passage of mcl1-1 into or through mitosis was equally lethal.

FIG. 7.

mcl1-1 requires the DNA damage checkpoint but is partially rescued by cds1Δ. (A) mcl1-1, cdc25-22, wee1-50, mcl1-1 cdc25-22, mcl1-1 wee1-50, and mcl1-1 bub1Δ cells were grown at 25°C to early log phase and shifted to the restrictive temperature of 36°C. Samples were taken every hour to determine viability upon return to the permissive temperatures. The graph presents means ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments. (B) cds1Δ mcl1-1 double mutants and cds1Δ mcl1-1 chk1Δ triple mutants were constructed. Survival of mcl1-1 cells was enhanced under permissive conditions by the deletion of cds1+. (C) Cds1p kinase activity was determined by its ability to phosphorylate the amino terminus of Wee1p. Lanes: 1, log-phase mcl1+ pREP42xcds1+ (3× HA); 2, mcl1+ pREP42xcds1+ (3× HA) arrested with 12 mM HU for 3 h; 3, mcl1+ pREP42cds1-KD (3× HA) arrested with 12 mM HU for 3 h; 3, mcl1-1 pREP42xcds1+ (3× HA) in log phase; 4, mcl1-1 pREP42xcds1+ (3× HA) arrested with 12 mM HU for 3 h; 6, mcl1-1 pREP42xcds1KD (3× HA) arrested with 12 mM HU for 3 h. The top panel is the kinase assay, and the bottom panel is a Western blot with an anti-HA. IgG, immunoglobulin G. (D) Overexpression of either Cds1p or Cds1KDp from an inducible promoter was toxic to mcl1-1 cells. The mcl1+ (strain 99) and mcl1-1 (strain 546) isogenic strains carried pREP42xcds1+ (3× HA) and pREP42xcds1-KD (3× HA) grown on selective medium. Plasmid expression was repressed by the addition of thiamine and induced by its absence. Wt, wild type.

mcl1-1 is partially rescued by cds1Δ but is synthetically lethal with rad3Δ and rad26Δ.

We determined the DNA damage checkpoint components important for mcl1-1 viability. In this study, 44 four-spore tetrads were examined for each cross. We were unable to recover the mcl1-1 rad3Δ or mcl1-1 rad26Δ double mutants but did recover the mcl1-1 rad1Δ and mcl1-1 rad9Δ double mutants, albeit they were very sickly (Table 2). We readily recovered the mcl1-1 cds1Δ and mcl1-1 chk1Δ double mutants. The mcl1-1 chk1Δ double mutants looked indistinguishable from the mcl1-1 single mutants; however, growth of the mcl1-1 cds1Δ double mutants was more robust. These mutants displayed a shorter G2 than mcl1-1 mutants but were still restricted for growth at 36°C (Fig. 7B). Triple mutants were recovered as nonparental ditype tetrads from crosses between the mcl1-1 cds1Δ and mcl1-1 chk1Δ strains (backcrosses confirmed the presence of both deletions). Even though spore viability from these meioses was severely decreased, recovered strains looked and grew indistinguishable from the mcl1-1 cds1Δ strains (Fig. 7B). Alleviation of the mcl1-1 mitotic delay phenotype by cds1Δ suggests that the cell cycle delay seen in mcl1-1 cells was principally due to Cds1p but that the delay was not essential for mcl1-1 viability at permissive temperatures.

Cds1p was initially identified in fission yeast as a high-copy-number suppressor of the Polα mutant swi7-H4, where it acts to enforce the S/M checkpoint; it is also an S-phase regulator important for replication damage recovery (45, 50). To determine if Cds1p activation in mcl1-1 cells could explain the slow-growth phenotypes observed at permissive temperatures, we constructed mcl1-1 rad26-T12 double mutants. rad26-T12 is defective in Cds1p activation (45), and we expected that mcl1-1 rad26-T12 mutants would be rescued for slow growth if Cds1p were constitutively activated by the mcl1-1 mutation. No synthetic growth phenotypes were seen, suggesting that Cds1p is not activated in mcl1-1 cells, at least not by Rad3p/Rad26p (data not shown). To confirm that Cds1p was not being activated by another mechanism, we assayed Cds1p kinase activity by immunoprecipitation of hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged alleles of cds1+ and cds1-KD (kinase dead) from mcl1-1 and mcl1+ cells (61). Kinase activity was measured with the N-terminal 70 aa of Wee1 fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) as substrate (8). In both strains, Cds1p kinase activity was undetectable in log-phase cells and in cells carrying the kinase-dead allele but it was highly active following a 3-h incubation in 12 mM HU (Fig. 7C, top panel). This suggested either that Cds1p activation was not responsible for the mcl1-1 slow-growth phenotype or that this assay was too insensitive to detect the low levels of Cds1 activity that may be sufficient for checkpoint delay. Interestingly, we noticed that the induction of either Cds1-HAp or Cds1KD-HAp expression dramatically inhibited mcl1-1 growth (Fig. 7D). This was most apparent in mcl1-1 cells carrying pREP42X cds1-KD HA when comparing induced and uninduced growth at the semipermissive temperature of 32°C. We inferred from this result that Cds1p is a molecular poison to mcl1-1 cells.

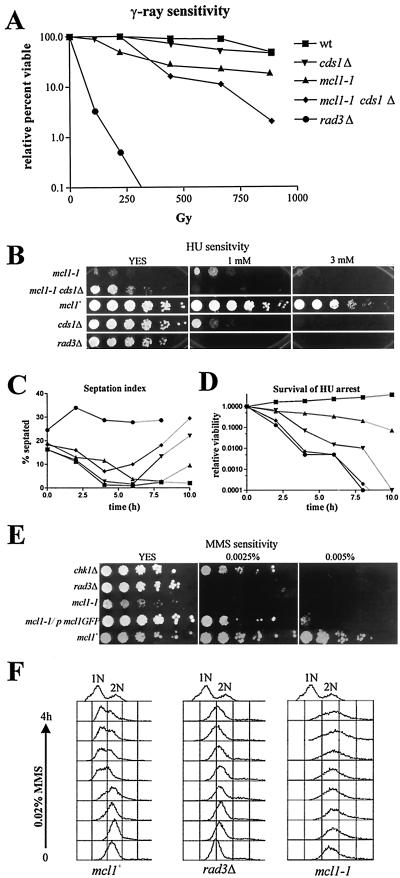

DNA metabolism is compromised in mcl1-1 cells.

The genetic interactions of mcl1-1 with a specific subset of the DNA damage checkpoint pathway suggested that the product of this locus could be affecting specific DNA repair functions that are essential for normal vegetative growth. To identify affected pathways, we tested mcl1-1 cells for sensitivity to the damage caused by UV, HU, γ-irradiation, and MMS. The mcl1-1 mutant showed only slight sensitivity to UV compared to that for the mcl1+ and checkpoint mutants, suggesting that nucleotide excision repair in mcl1-1 was mostly intact. However, γ-irradiation, which induces double-strand breaks, led to the significantly decreased viability of the mcl1-1 mutant compared to that of wild-type strains. Surprisingly, the mcl1-1 cds1Δ double mutant showed synergistic sensitivity to γ-irradiation compared with that of either single mutant (Fig. 8A). mcl1-1 cells were also hypersensitive to growth in the continual presence of HU. Prolonged HU treatment is believed to cause fork collapse, and mutants sensitive to HU are either defective in S/M checkpoint delay, like rad3Δ, or recovery from this arrest, like rqh1Δ and cds1Δ (56). The mcl1-1 mutant was unable to grow in the continual presence of 3 mM HU. The mcl1-1 cds1Δ double-mutant strains, like rad3Δ, could not grow in the presence of 1 mM HU (Fig. 8B), suggesting synergy between these two mutations in the cellular response to HU. The mcl1-1and cds1Δ single mutants as well as the mcl1-1 cds1Δ double mutants blocked cell cycle progression as assessed by a decrease in septation index (Fig. 8C and data not shown), but unlike the mcl1-1 mutant alone, which maintained a high viability of up to 6 h (Fig. 8D), the cds1Δ mcl1-1 double mutants showed a similar sensitivity to HU as did rad3Δ and they showed an abbreviated arrest. This implies that Cds1p and Mcl1p function in separate pathways that ensure proper replication arrest and recovery.

FIG. 8.

mcl1-1 is sensitive to DNA damage. (A) Wild-type (wt; strain 99), mcl1-1 (strain 546), cds1Δ (strain FY865), mcl1-1 cds1Δ (strain 563), and rad3Δ (strain FY1105) cells were exposed to the indicated γ-ray doses. Relative viability is plotted. (B) mcl1-1 cell growth is hypersensitive to the continual presence of 3 mM HU. The mcl1-1 cds1Δ mutant (strain 563) is more sensitive to HU than either single mutant, and its sensitivity is similar to that of the rad3Δ mutant (strain FY1105). (C) Only a checkpoint-defective strain, rad3Δ, failed to arrest cell division in response to 12 mM HU, as indicated by the septation index. (D) mcl1-1 cells are sensitive to a prolonged arrest in HU but not as sensitive as checkpoint-defective strains. (E) mcl1-1 cells are as sensitive to MMS as are rad3Δ cells and are unable to grow in the presence of 0.0025% MMS. Sensitivity of mcl1-1 cells is rescued by pREP42x expression of mcl1-GFP. (F) FACS analysis of the mcl1+(strain 99), rad3Δ (strain FY1105), and mcl1-1 (strain 546) cultures treated with 0.02% MMS is illustrated. mcl1-1 cells had a much weaker arrest in S phase than did mcl1+ cells (strain 99). This is similar to the rad3Δ phenotype. 1N and 2N reference peaks were generated by a mix of cdc10-129 and cdc25-22 cells arrested for 2.5 h at 36°C.

Like ctf4Δ, mcl1-1 was also hypersensitive to the DNA alkylating agent MMS, which can block S-phase progression. Overcoming MMS toxicity requires the recruitment of replicative repair polymerases to perform base excision repair (BER) or replication bypass (33, 75). mcl1-1 cells were unable to grow in the continual presence of 0.0025% MMS. This sensitivity was indistinguishable from that of rad3Δ cells (Fig. 8E). We tested log-phase cultures treated with 0.02% MMS for S-phase checkpoint delay effects. Log-phase mcl1+ cells so treated for 4 h showed <60% of the cells delayed in S phase (Fig. 8F, left histograms), whereas treated rad3Δ cells did not delay replication (middle histograms). The mcl1-1 mutant appeared less delayed in S phase than mcl1+ cells (right histograms) and lost viability by 3 h, suggesting that mcl1-1 is defective in BER and perhaps in S-phase arrest as well.

DISCUSSION

Mcl1p belongs to a conserved eukaryotic family of proteins found in plants, fungi, and animals that is essential for chromosome maintenance in fungi. This family of proteins contains two recognizable motifs: an N-terminal WD40 domain, followed by three unique, highly conserved sepB boxes. In vertebrate members, there is also a C-terminal high-mobility-group AT hook DNA binding domain (13, 40). Since Ctf4p has only a single WD40 repeat—inadequate to form the β-propeller structure of a G-beta-like molecule—the highly conserved sepB boxes represent the only unique feature that is common to all family members and distinguishes this family from the myriad of other WD40 domain proteins. WD40 proteins are typically regulatory and have never been described to possess enzymatic function. Therefore, the sepB domains most likely represent an additional interaction domain unique to this family and possibly to its function.

sepB3, ctf4Δ, and mcl1-1 cells all have strong chromosome missegregation phenotypes, with ctf4Δ and mcl1-1 cells showing defects in sister-chromatid cohesion (Fig. 1). The segregation of chromosomes during mitosis is dependent on sister kinetochores achieving a bipolar attachment to spindle MTs. Kinetochores become so oriented because newly replicated sister chromatids maintain cohesion until tension is generated at kinetochores and anaphase onset is triggered. Tension generated by cohesion is monitored by the spindle assembly checkpoint, and the absence of cohesion has been shown to activate the spindle assembly checkpoint (64). This blocks the cascade of events that initiate the dissolution of cohesion, anaphase onset, and mitotic progression (10). ctf18Δ and ctf4Δ cells exhibit a cell cycle delay dependent on mad2Δ, but it is unknown if this contributes to cell viability (29). In this study, the viability of mcl1-1 cells was dependent on the spindle assembly checkpoint protein Bub1p but not Mad2p. When Bub1p is present, mcl1-1 cells show a mitotic delay in cells that missegregate chromosomes, suggesting that it is the absence of cohesion that triggers the spindle checkpoint and that this is important for mcl1-1 viability. This is further supported by the observation that mcl1-1 was sensitive to the MT poison TBZ and was lethal in combination with the cohesin mutant rad21-K1 (Fig. 1). These multiple observations support the conclusion that mcl1-1 missegregates chromosomes due to defective sister-chromatid cohesion.

Neither sepB3 cells nor mcl1-1 cells accumulate in mitosis, suggesting that cells predominately arrest in G2, which differs from the recent observation that the ctf4-s65 arrest is enforced by Mad2p and is therefore mitotic. S. pombe is an excellent system in which to test the relative importance of the DNA damage versus the spindle assembly checkpoints' impact on cell viability, because of the well-defined G2-to-M transition and the clear role of available cell cycle mutants. We found passage into or through mitosis to be equally detrimental to mcl1-1 cells at 36°C, suggesting that any progression toward cell division was lethal to mcl1-1 cells. Further, the loss of Mcl1p function must damage DNA in a way that specifically requires the Rad3/Rad26 DNA checkpoint complex for repair and viability, since we found that none of the other DNA damage checkpoint components were essential for mcl1-1 viability. Similar but less severe dependency on the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated and ataxia-telangiectasia-related checkpoint kinases has been described in sepB3 and ctf4Δ cells, where sepB3 delay of septation during conidiation is alleviated by the uvsB110 mutation and ctf4Δ has a dramatically reduced viability in combination with mec1-1 (30, 31, 48). Chromosomes appear heterogeneous in mcl1-1 cells, and this phenotype is enhanced by growth at 36°C. This is likely to occur both from low replication fidelity, as suggested by the longer, heterogeneous telomeres and from chromosomal shearing during anaphase, seen in chromatin bridges during live cell observations.

The growing number of yeast replication components important for cohesion supports the polymerase-switching model for the replication-mediated establishment of cohesion (29, 47, 59, 68, 70, 71, 77, 83). Trf4p in S. cerevisiae belongs to the β-polymerase family of DNA replication repair polymerases and is required for the establishment of cohesion, as well as for the replication of topologically constrained DNA (82). It has been proposed that the alternative RFC (Ctf8p, Ctf18p, and Ddc1p) complex important for cohesion promotes the loading of Trf4p (Polσ) in regions of the genome where replication forks become blocked by chromatin structures, such as sites occupied by cohesins. The relationship between TRF4, this novel RFC complex (which includes Ctf18p), and cohesins has not yet been established, but Ctf4p would be an attractive link between the alternative RFC complex and the primer template since ctf4Δ is synthetically lethal with ctf18Δ and Ctf4p physically interacts with Polα, the replication primase in eukaryotes.

β-Polymerases are essential for the replicative repair of DNA damage, suggesting that mutants defective in β-polymerase switching may also be sensitive to genotoxic stress that requires BER (55). Both ctf4Δ and mcl1-1 cells are hypersensitive to MMS, which is repaired by BER pathways (Fig. 8E) (48). mcl1-1 cells, in comparison to the wild type, do not have a strong S-phase delay in response to 0.02% MMS treatment (Fig. 8F). This hypersensitivity to MMS and a diminished S-phase delay suggest that mcl1-1 cells do not properly respond to MMS damage during replication. Given that Dna2p, which has been reported to be involved in DNA damage repair and lagging strand DNA synthesis (37), can partially rescue this sensitivity when overproduced, mcl1-1 cells may simply be deficient in efficiently recruiting the replicative repair machinery to damaged sites and thus may favor mutagenic replicative bypass repair over BER repair (65, 81).

We have also found that mcl1-1 has strong interactions with other DNA replication components. mcl1-1 was lethal in combination with cdc24-M38 (Table 2). Cdc24p is involved in polymerase loading, as it genetically and physically interacts with Pcn1p (PCNA) and Rfc1p in fission yeast (69). Moreover, rqh1Δ and rqh1-HD were lethal in combination with the mcl1-1 mutant. Rqh1p, the fission yeast RecQ helicase homologue, is a DNA structure-specific helicase that is important for the replication of topologically constrained regions of the genome and genomic stability (17). These data suggest that mcl1-1 is important for efficient DNA synthesis and possibly for the replication of topologically constrained DNA. Moreover, mcl1-1 in combination with the replication initiator kinase mutant hsk1-1312 allele is lethal. These two mutants independently share a number of phenotypes: both have reduced sister-chromatid cohesion, both are partially rescued by the deletion of cds1+, both are synthetically lethal with rqh1Δ, and both show extreme sensitivity to HU and MMS (61, 68). Unfortunately, the functional relationship between Mcl1p and Hsk1p remains to be determined in this study. The interactions between Hsk1p and Cds1p kinases appear to be complex, as Hsk1p is both a substrate and an activator of Cds1p, though the effect of Hsk1 phosphorylation by Cds1p has not yet been determined (61, 68). Thus, the relationship of Mcl1p to these two known S-phase regulators remains difficult to specify but they nevertheless appear intertwined.

The synergistic sensitivity of cds1Δ mcl1-1 cells toward HU is similar in degree to that of rad3Δ cells (Fig. 8C), which completely lack a checkpoint response. This result suggests that Cds1p acts in concert with Mcl1p for proper HU tolerance. We also found that the deletion of cds1+ partially rescued mcl1-1 slow growth, suggesting that it is primarily responsible for the late-S or G2 phase delay in mcl1-1 cells. This interpretation requires Cds1 activation in mcl1-1 cultures, but we found no detectable Cds1p activation nor any defect in its activation. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that our assay was not sensitive enough to detect a Cds1 kinase activity that could be sufficient for checkpoint delay. Given that both kinase-active and kinase-dead alleles of Cds1p can act as molecular poisons to mcl1-1 growth under permissive conditions, we believe Cds1p regulates a pathway that may be deleterious to mcl1-1 viability. One known target of Cds1p, possibly independent of its kinase activity, is the regulation of the Mus81 Holliday junction resolvase (14). If HU-stalled replication forks collapse, the reinitiation of replication from these collapsed forks would require both helicase and resolvase activity, such as that described for Rqh1p and Mus81p (9, 27, 65). Unfortunately, the functional implications of the Cds1p-Mus81p interaction are not known, but these data suggest that S. pombe cells with diminished Mcl1p carry out DNA replication that is sensitive to both the presence of Cds1p and the absence of Hsk1p and Rqh1p.

The best-understood role of the Dfp1/Hsk1 kinase (DDK) is to initiate DNA replication (12, 46). Therefore, the increased accumulation of cells with less than 2N DNA in an hsk1-1312 culture, when Mcl1-PK is in excess, suggests that Mcl1p can antagonize either processive DNA replication or its initiation. Such a role is supported by our observations that overexpression of Mcl1p in wild-type cells also leads to a cell cycle delay with a less than 2N DNA content. However, this effect at extremely high levels of Mcl1p overexpression in wild-type cultures is not as dramatic as that found in hsk1-1312 cells overexpressing Mcl1p to much lesser extent, possibly because hsk1-1312 cells are already compromised in S-phase progression at 29°C. The Dfp1p/Hsk1p role in DNA replication initiation is believed to result from its phosphorylation of a number of replication fork components, such as Mcm2p (12, 68). We have found no evidence for Mcl1p phosphorylation (our unpublished observations), although some WD40 domain proteins specifically recognize phosphorylated binding partners (85). This leaves open the possibility that Mcl1p may be regulated not by being a substrate for phosphorylation but by recognizing the modification of its binding partner(s).

The identification of Ctf4p as a Polα binding protein suggests a possible mechanism for the blocking of DNA replication. Competition for binding to Polα between Ctf4p and the Cdc68p/Pob3p chromatin-remodeling complex could be a point of regulation for replication fork initiation or progression. Cdc68p/Pob3p and a homologous complex in Xenopus sp. (DNA unwinding factors p87/p140) are essential for efficient replication initiation (52, 58). If Mcl1p, like CTF4, acts to restrict access to Polα, then an excess of Mcl1p in a kinase-compromised Hsk1 mutant would be expected to block postinitiation DNA replication. This hypothesis remains to be tested, however, and will require detailed protein interaction analysis, a current focus in our lab.

Eukaryotic DNA replication is distinct from bacterial DNA replication in that it requires multiple polymerases. Indeed, both DNA repair and recombination require selective recruitment of or access to the templates of specific polymerases (66). The mechanism of genomic instability exhibited by the CTF4, mcl1+, and sepB mutants, as well as the genetic and physical interactions with DNA replication and repair components, suggests that this family of eukaryotic proteins has an important role in regulating polymerase-containing complexes. The importance of these proteins in fungi suggests that further investigation into their response to DNA damage and protein interaction partners may be important to our understanding of polymerase regulation and genomic stability in all eukaryotes.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Freyer, S. Sazar, L. Clarke, A. M. Carr, M. J. O'Connell, J. P. Javerzat, I. Hagan, A. Yamamoto, P. Russell, and D. Q. Ding for yeast strains and reagents. We particularly thank Susan Forsburg and her lab for helpful advice, keen interest, and yeast strains.

D.R.W. was supported by training grant GM07135 to W. B. Wood. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM-33787 to J.R.M., who is a research professor for the American Cancer Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agar, D. W., and J. E. Bailey. 1982. Cell cycle operation during batch growth of fission yeast populations. Cytometry 3:123-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiyar, A. 2000. The use of CLUSTAL W and CLUSTAL X for multiple sequence alignment. Methods Mol. Biol. 132:221-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumann, P., and T. R. Cech. 2000. Protection of telomeres by the Ku protein in fission yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3265-3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard, P., J.-F. Maure, J. F. Partridge, S. Genier, J.-P. Javerzat, and R. C. Allshire. 2001. Requirement of heterochromatin for cohesion at centromeres. Science 294:2539-2542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Birkenbihl, R. P., and S. Subramani. 1992. Cloning and characterization of rad21, an essential gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe involved in DNA double-strand-break repair. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:6605-6611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blat, Y., and N. Kleckner. 1999. Cohesins bind to preferential sites along yeast chromosome III, with differential regulation along arms versus the centric region. Cell 98:249-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boddy, M. N., B. Furnari, O. Mondesert, and P. Russell. 1998. Replication checkpoint enforced by kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Science 280:909-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boddy, M. N., A. Lopez-Girona, P. Shanahan, H. Interthal, W. D. Heyer, and P. Russell. 2000. Damage tolerance protein Mus81 associates with the FHA1 domain of checkpoint kinase Cds1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:8758-8766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brady, D. M., and K. G. Hardwick. 2000. Complex formation between Mad1p, Bub1p and Bub3p is crucial for spindle checkpoint function. Curr. Biol. 10:675-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridge, A. J., M. Morphew, R. Bartlett, and I. M. Hagan. 1998. The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 12:927-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown, G. W., and T. J. Kelly. 1999. Cell cycle regulation of Dfp1, an activator of the Hsk1 protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8443-8448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bustin, M. 2001. Revised nomenclature for high mobility group (HMG) chromosomal proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26:152-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, X. B., R. Melchionna, C. M. Denis, P. H. Gaillard, A. Blasina, I. Van de Weyer, M. N. Boddy, P. Russell, J. Vialard, and C. H. McGowan. 2001. Human Mus81-associated endonuclease cleaves Holliday junctions in vitro. Mol. Cell 8:1117-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper, J. P., E. R. Nimmo, R. C. Allshire, and T. R. Cech. 1997. Regulation of telomere length and function by a Myb-domain protein in fission yeast. Nature 385:744-747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Craven, R. A., D. J. Griffiths, K. S. Sheldrick, R. E. Randall, I. M. Hagan, and A. M. Carr. 1998. Vectors for the expression of tagged proteins in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 221:59-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davey, S., C. S. Han, S. A. Ramer, J. C. Klassen, A. Jacobson, A. Eisenberger, K. M. Hopkins, H. B. Lieberman, and G. A. Freyer. 1998. Fission yeast rad12+ regulates cell cycle checkpoint control and is homologous to the Bloom's syndrome disease gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2721-2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding, D. Q., Y. Tomita, A. Yamamoto, Y. Chikashige, T. Haraguchi, and Y. Hiraoka. 2000. Large-scale screening of intracellular protein localization in living fission yeast cells by the use of a GFP-fusion genomic DNA library. Genes Cells 5:169-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fan, X., and C. M. Price. 1997. Coordinate regulation of G- and C strand length during new telomere synthesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:2145-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fincham, J. R. 1989. Transformation in fungi. Microbiol. Rev. 53:148-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fleig, U., M. Sen-Gupta, and J. H. Hegemann. 1996. Fission yeast mal2+ is required for chromosome segregation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6169-6177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Formosa, T., and T. Nittis. 1999. Dna2 mutants reveal interactions with Dna polymerase alpha and Ctf4, a Pol alpha accessory factor, and show that full Dna2 helicase activity is not essential for growth. Genetics 151:1459-1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forsburg, S. L. 1993. Comparison of Schizosaccharomyces pombe expression systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 21:2955-2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furnari, B., A. Blasina, M. N. Boddy, C. H. McGowan, and P. Russell. 1999. Cdc25 inhibited in vivo and in vitro by checkpoint kinases Cds1 and Chk1. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:833-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goshima, G., S. Saitoh, and M. Yanagida. 1999. Proper metaphase spindle length is determined by centromere proteins Mis12 and Mis6 required for faithful chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13:1664-1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gould, K. L., C. G. Burns, A. Feoktistova, C. P. Hu, S. G. Pasion, and S. L. Forsburg. 1998. Fission yeast cdc24(+) encodes a novel replication factor required for chromosome integrity. Genetics 149:1221-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haber, J. E., and W. D. Heyer. 2001. The fuss about Mus81. Cell 107:551-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hagan, I. M., and J. S. Hyams. 1988. The use of cell division cycle mutants to investigate the control of microtubule distribution in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 89:343-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28a.Hahnenberger, K. M., M. P. Baum, C. M. Polizzi, J. Carbon, and L. Clarke. 1989. Construction of functional artificial minichromosomes in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:577-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna, J. S., E. S. Kroll, V. Lundblad, and F. A. Spencer. 2001. Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTF18 and CTF4 are required for sister chromatid cohesion. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:3144-3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris, S. D., and J. E. Hamer. 1995. sepB: an Aspergillus nidulans gene involved in chromosome segregation and the initiation of cytokinesis. EMBO J. 14:5244-5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris, S. D., and P. R. Kraus. 1998. Regulation of septum formation in Aspergillus nidulans by a DNA damage checkpoint pathway. Genetics 148:1055-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He, X., T. E. Patterson, and S. Sazer. 1997. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe spindle checkpoint protein mad2p blocks anaphase and genetically interacts with the anaphase-promoting complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:7965-7970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoeijmakers, J. H. 2001. Genome maintenance mechanisms for preventing cancer. Nature 411:366-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hood, M. T., and C. Stachow. 1990. Transformation of Schizosaccharomyces pombe by electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:688.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Javerzat, J. P., G. Cranston, and R. C. Allshire. 1996. Fission yeast genes which disrupt mitotic chromosome segregation when overexpressed. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4676-4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnston, L. H., and A. P. Thomas. 1982. The isolation of new DNA synthesis mutants in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 186:439-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang, H. Y., E. Choi, S. H. Bae, K. H. Lee, B. S. Gim, H. D. Kim, C. Park, S. A. MacNeill, and Y. S. Seo. 2000. Genetic analyses of Schizosaccharomyces pombe dna2(+) reveal that dna2 plays an essential role in Okazaki fragment metabolism. Genetics 155:1055-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kearsey, S. E., S. Montgomery, K. Labib, and K. Lindner. 2000. Chromatin binding of the fission yeast replication factor mcm4 occurs during anaphase and requires ORC and cdc18. EMBO J. 19:1681-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim, S. T., B. Xu, and M. B. Kastan. 2002. Involvement of the cohesin protein, Smc1, in Atm-dependent and independent responses to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 16:560-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kohler, A., M. S. Schmidt-Zachmann, and W. W. Franke. 1997. AND-1, a natural chimeric DNA-binding protein, combines an HMG-box with regulatory WD-repeats. J. Cell Sci. 110:1051-1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kouprina, N., E. Kroll, V. Bannikov, V. Bliskovsky, R. Gizatullin, A. Kirillov, B. Shestopalov, V. Zakharyev, P. Hieter, F. Spencer, et al. 1992. CTF4 (CHL15) mutants exhibit defective DNA metabolism in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:5736-5747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kouprina, N., O. B. Pashina, N. T. Nikolaishwili, A. M. Tsouladze, and V. L. Larionov. 1988. Genetic control of chromosome stability in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 4:257-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Larionov, V. L., N. Y. Kouprina, A. V. Strunnikov, and A. V. Vlasov. 1989. A direct selection procedure for isolating yeast mutants with an impaired segregation of artificial minichromosomes. Curr. Genet. 15:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee, J. Y., and T. L. Orr-Weaver. 2001. The molecular basis of sister-chromatid cohesion. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17:753-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lindsay, H. D., D. J. Griffiths, R. J. Edwards, P. U. Christensen, J. M. Murray, F. Osman, N. Walworth, and A. M. Carr. 1998. S-phase-specific activation of Cds1 kinase defines a subpathway of the checkpoint response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 12:382-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Masai, H., T. Miyake, and K. Arai. 1995. hsk1+, a Schizosaccharomyces pombe gene related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae CDC7, is required for chromosomal replication. EMBO J. 14:3094-3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mayer, M. L., S. P. Gygi, R. Aebersold, and P. Hieter. 2001. Identification of RFC (Ctf18p, Ctf8p, Dcc1p): an alternative RFC complex required for sister chromatid cohesion in S. cerevisiae. Mol. Cell 7:959-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miles, J., and T. Formosa. 1992. Evidence that POB1, a Saccharomyces cerevisiae protein that binds to DNA polymerase α, acts in DNA metabolism in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:5724-5735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreno, S., A. Klar, and P. Nurse. 1991. Molecular genetic analysis of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194:795-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Murakami, H., and H. Okayama. 1995. A kinase from fission yeast responsible for blocking mitosis in S phase. Nature 374:817-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohi, R., A. Feoktistova, and K. L. Gould. 1996. Construction of vectors and a genomic library for use with his3-deficient strains of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 174:315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okuhara, K., K. Ohta, H. Seo, M. Shioda, T. Yamada, Y. Tanaka, N. Dohmae, Y. Seyama, T. Shibata, and H. Murofushi. 1999. A DNA unwinding factor involved in DNA replication in cell-free extracts of Xenopus eggs. Curr. Biol. 9:341-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]