Abstract

It is now universally recognized that only a portion of aquatic bacteria is actively growing, but quantitative information on the fraction of living versus dormant or dead bacteria in marine sediments is completely lacking. We compared different protocols for the determination of the dead, dormant, and active bacterial fractions in two different marine sediments and at different depths into the sediment core. Bacterial counts ranged between (1.5 ± 0.2) × 108 cells g−1 and (53.1 ± 16.0) × 108 cells g−1 in sandy and muddy sediments, respectively. Bacteria displaying intact membrane (live bacterial cells) accounted for 26 to 30% of total bacterial counts, while dead cells represented the most abundant fraction (70 to 74%). Among living bacterial cells, nucleoid-containing cells represented only 4% of total bacterial counts, indicating that only a very limited fraction of bacterial assemblage was actively growing. Nucleoid-containing cells increased with increasing sediment organic content. The number of bacteria responsive to antibiotic treatment (direct viable count; range, 0.3 to 4.8% of the total bacterial number) was significantly lower than nucleoid-containing cell counts. An experiment of nutrient enrichment to stimulate a response of the dormant bacterial fraction determined a significant increase of nucleoid-containing cells. After nutrient enrichment, a large fraction of dormant bacteria (6 to 11% of the total bacterial number) was “reactivated.” Bacterial turnover rates estimated ranged from 0.01 to 0.1 day−1 but were 50 to 80 times higher when only the fraction of active bacteria was considered (on average 3.2 day−1). Our results suggest that the fraction of active bacteria in marine sediments is controlled by nutrient supply and availability and that their turnover rates are at least 1 order of magnitude higher than previously reported.

Natural bacterial assemblages display different metabolic levels and vital states. For a long time it has been assumed that all bacteria stained using fluorochromes were alive (15, 19, 27), but now it is universally recognized that only a portion of aquatic bacteria is alive and actively growing, while a large fraction is dormant or dead (1, 8, 11, 22, 29, 30, 31, 32). The quantification of the fraction actually responsible for bacterial activity (C production and enzymatic activities) is of primary relevance for addressing important ecological questions involving organic matter degradation rates and nutrient cycling, as well as factors controlling these processes (16). Bacterial turnover rates calculated on total bacterial numbers are too variable (oscillating in different systems from hours to months) to be realistic, especially when compared to those derived from plate cultures (9), and there is a lack of information on actual bacterial turnover rates (i.e., based on actively growing bacteria [39]). Approaches for discriminating between living and dead cells are based on cell integrity, which can be investigated using molecular probes able to penetrate bacterial membranes and cell walls only when they are compromised (23, 30), but membrane integrity is not sure proof of activity. In fact, some bacteria with intact membranes might not display a visible nucleoid region (non-nucleoid-containing cells [non-NuCC], i.e., apparently without DNA), which has been recently utilized as an indicator of the active bacterial metabolic state (39). However, since non-NuCC have been cultured, it is possible that their DNA can be dispersed in the cell in periods of low activity; therefore, non-NuCC could be either dead or inactive (5). The comparison of the results from a method based on cell integrity with the results from the one based on NuCC allows one to estimate the number of dormant cells (as the difference between the number of live cells and number of NuCC [12]). Another possible way to estimate the number of viable bacteria (direct viable count [DVC]) is based on incubations with antibiotics, which inhibit DNA synthesis without affecting other cellular metabolic activities (16, 20).

Despite the ecological role and significance of benthic bacteria in biogeochemical cycles on a global scale, information on the metabolic and physiological state of bacteria in marine sediments is extremely scarce (9, 17, 28, 33). Moreover, information on the fraction of active versus dormant benthic bacterial cells is completely lacking.

In this study we estimated the fraction of bacteria actively contributing to bacterial carbon production and calculated the actual turnover rate of actively growing bacteria in different marine sediments and at different depths into the sediment core (sand versus mud and surface aerobic versus subsurface hypoxic sediments). To do this, we compared total direct counts (using both acridine orange and SYBR Green I [Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) with the number of dead or live bacteria (determined using dual fluorochrome staining SYBR Green I-propidium iodide [PI]]). Then we estimated the fraction of active versus dormant bacteria using both the NuCC protocol and the DVC based on incubations with a cocktail of antibiotics. Finally, we conducted microcosm experiments to estimate the fraction of dormant bacteria that was inducible to active metabolism after organic and inorganic nutrient supply, to quantify the “dormant-reactivated” bacterial fraction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sampling.

Undisturbed sediment cores were collected using a multiple corer in the central Adriatic Sea. Two stations were selected in this study: one was located inside (43°37′.320 N, 13°29′.971 E, and 12.4-m depth) and one outside (43°37′.26 N, 13°29′.00 E, and 9-m depth) the Ancona harbor (Italy). The station inside the harbor was characterized by muddy sediments (sand, 30.6%; silt, 40.9%; and clay, 28.5%; water content, 47.0%), while the station outside displayed a coarser grain composition (sand, 92.8%; silt, 6.8%; and clay, 0.4%; water content, 22.2%). The two stations displayed completely different organic matter content and composition; total organic matter content ranged between 11.6 and 0.7% (dry weight) of sediment (inside and outside the harbor, respectively). Sediment chlorophyll a ranged between 16.4 and 2.0 μg g−1, respectively, and sediment proteins ranged between 8,211.3 and 550.0 μg g−1 (inside and outside, respectively). The in situ temperature was 15°C at both stations. Sediment cores (6-cm diameter and 20-cm length) were kept at in situ temperature (16°C) until laboratory analysis.

Experimental plan.

Two sediment layers were collected from both stations: the top was 0 to 1 cm deep and the layer was 5 to 8 cm deep. They displayed oxygenated (Eh > 200 mV) and suboxic conditions (−200<Eh < 200 mV), respectively. From each layer, three replicates of 20 ml of sediment were transferred into sterile Falcon tubes, supplemented with 20 ml of prefiltered (0.2-μm pore size) seawater (37 practical salinity units [PSU]) collected in situ, and processed, within 1 h of sampling, after gentle homogenization with a sterile spatula. All determinations were carried at in situ temperature.

Total bacterial counts.

Total bacterial counts were performed both using the acridine orange direct count (AODC [7]) and SYBR Green I direct count (SGDC [25]). Replicate (n = 3) sediment subsamples of 1 ml, withdrawn from each sediment sample, were transferred into sterile test tubes and fixed with 4 ml of prefiltered (0.2-μm pore size) and buffered 2% formalin. Subsamples were sonicated three times (Branson Sonifier 2200; 60 W for 1 min) and were diluted 250 to 500 times with sterile and prefiltered (0.2-μm pore size) formalin (2% final concentration).

For AODC, subsamples were stained for 5 min with acridine orange (final concentration, 5 mg liter−1) and were filtered on black Nuclepore polycarbonate 0.2-μm-pore-size filters at ≤100 mm Hg. Filters were washed twice with 3 ml of sterilized Milli-Q water and were mounted on microscope slides. For SGDC, sediment subsamples were concentrated on 0.2-μm-pore-size aluminum oxide filters (Anodisc) and were then stained with SYBR Green I by supplementing on each filter 10 μl of the stock solution (previously diluted 1:20 with filtered [0.2-μm-pore-size] Milli-Q water) to a final concentration of 1:100. Filters were analyzed using epifluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×1,000; filter beam splitter, 510 nm; long-pass, 520 nm; Zeiss Axioskop 2). For each slide at least 10 microscope fields were observed and at least 400 cells were counted per filter. Bacterial size was measured (as maximal length and width) using a micrometer on all cells counted. The bacterial biovolume was converted to carbon content assuming 310 fg of C μm−3 (10). Data were normalized to sediment dry weight after desiccation (60°C, 24 h).

Counting live and dead bacteria.

In this study live bacterial cells (LBC) were assumed to display intact membranes and cell walls. To assess the number of LBC, we used a double-staining method requiring SYBR Green I and PI (PI solution: 5 mg of fluorochrome in 5 ml of Milli-Q water [2]). The rationale of this approach is that SYBR Green I (stock solution [Molecular Probes], 1:20 [vol:vol] in Milli-Q) stains both live and dead bacteria (green fluorescence; filter specifications, band-pass, 450 to 490 nm; and long-pass, 520 nm [23]), while PI is able to penetrate only damaged or dead cells (red fluorescence under green light; long-pass, 510 and 590 nm) (37). Sediment subsamples (n = 3; 1 ml) were treated with 4 ml of filtered (0.2-μm pore size) seawater and were diluted 250 to 500 times. Aliquots were filtered onto 0.2-μm-pore-size aluminum oxide Anodisc filters under low vacuum (<100 mm Hg) and were supplemented with 10 μl of SYBR Green I and 10 μl of PI (in the dark for 20 min). After staining, filters were mounted on microscope slides with 50% glycerol and 50% phosphate-buffered saline with 0.5% ascorbic acid (10 μl under and 10 μl over the filter).

NuCC.

To quantify the number of NuCC, we applied the method described for water samples (39) to the sediment with a few adaptations. The determination of the NuCC fraction is based on a destaining/staining procedure (39). Previous studies reported that formalin fixation of samples with salinity of >12 PSU hampered the 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining of nucleoid and suggested fixation with sodium azide (39), unless internal bacterial salinity was lowered before staining. The effects of formalin fixation on NuCC counts after staining with acridine orange are unknown; however, to avoid any possible bias related to salinity (39) and/or to the fixative, we lowered salinity by diluting samples with Milli-Q water and then performed analyses on both sediment subsamples fixed with formalin (2%) and with sodium azide (final concentration, 0.5 M [18]). A preincubation of 1 h (supplemented with acridine orange) was performed (18). After dilution with Milli-Q water (250 and 500 times for sandy and muddy sediments, respectively), samples were incubated for 2 h in the dark with acridine orange (final concentration 0.025%) and Triton X-100 (0.1% [vol/vol]) and were then filtered at 100 mm Hg onto 0.2-μm-pore-size Nuclepore filters (black-stained polycarbonate). Filters were washed with 10 ml of 2-propanol for 10 min before being mounted on microscopic slides. NuCC counts were carried out under epifluorescence microscopy (Zeiss Axioskop 2; magnification, ×1,000). According to the destaining/staining procedure (39), filters were washed once with 5 ml of sterile seawater and were then restained with acridine orange.

DVC.

DVC was carried out on sediment samples adapting the method based on a antibiotic cocktail recently proposed by Joux and LeBaron (16). From each sediment type, 6 ml of sediment slurry was transferred into 15-ml sterile tubes supplemented with 4 ml of filtered (0.2-μm pore size) seawater and with an antibiotic cocktail containing nalidixic acid (final concentration, 20 μg ml−1 in 0.05 M NaOH), pipemidic acid (10 μg ml−1 in 0.05 M NaOH), cephalexin (10 μg ml−1 in sterile water), and ciprofloxacin (0.5 μg ml−1 in sterile water). Samples were incubated for 8 to 24 h at in situ temperature. At the end of the incubations samples (n = 3) were fixed with formalin (final concentration, 2%), diluted, stained with acridine orange, and analyzed by epifluorescence microscopy.

Bacterial carbon production.

Bacterial production was measured by [3H]leucine incorporation for marine sediments (34). Sediment subsamples (200 μl), supplemented with an aqueous solution of [3H]leucine (specific activity, 61 Ci mmol−1; amount of leucine, 0.1 nmol; and final concentration, 6 μCi; Amersham), were incubated for 1 h in the dark at in situ temperature. After incubation, samples were supplemented with ethanol (80%) before scintillation counting. Sediment blanks were made supplementing ethanol immediately before the addition of [3H]leucine. Data were normalized to the sediment dry weight after desiccation (60°C, 24 h).

Dormant bacteria and dormant bacteria inducible to an active state (dormant-reactivated bacteria).

The total number of dormant bacteria was calculated as the difference between the numbers of LBC and NuCC. The percentage of bacteria inducible to an active state (reactivated bacterial cells [RBC]) was estimated as the difference between NuCC counts before and after nutrient supply and normalized to AODC. Dormant bacteria were stimulated to an active state by supplementing sediment subsamples with glucose (50 μM), albumin (50 μM), nitrate (16 μM), and phosphate (1 μM) (final concentrations). Sediment samples were incubated for 100 h in the dark at in situ temperature. Only superficial muddy and sandy sediments were investigated for RBC estimates.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Comparison of total bacterial counts.

Noble and Fuhrman (25) reported, for seawater samples, that SYBR Green I bacterial counts were identical to acridine orange counts. Since detritus particles were generally not (or faintly) stained, they suggested its use also for bacterial counting in aquatic sediments. Weinbauer et al. (36) did not find differences between DAPI and SYBR Green I bacterial counts in soil and sediment samples and recommended the use of SYBR Green I due to its brighter staining of cells. Also, a recent comparison of SYBR Green I performance and acridine orange performance in deep-sea sediments reported identical bacterial counts (7). Bacterial counts performed in this study using SYBR Green I and acridine orange yielded identical values in all sediment samples examined, with the exception of a single sample (sand top layer), in which AODCs were significantly higher (t test, P < 0.05 [Table 1 ]). We also found that bacterial biomass, determined using acridine orange and SYBR Green I, yielded comparable values in all sediment samples (Table 1). Given the identical performance of the two stains, in this study we used AODC for quantifying all bacterial parameters because this stain makes green-stained cells more clearly distinguishable from the orange-stained detritus than does SYBR Green I. This appears important, since sediment organic detritus is 10,000- to 100,000-fold more concentrated than in the water column. The only exception was for the live and dead count protocol, in which SYBR Green I counting was required.

TABLE 1.

Total bacterial counts and biomass, determined with acridine orange (AO) and SYBR Green I (SG), and bacterial carbon production (BCP)a

| Sediment type | Layer | Treatment | AODC (no. of cells g−1) (108) | SGDC (no. of cells g−1) (108) | Bacterial biomass (AO) (μg of C g−1) | Bacterial biomass (SG) (μg of C g−1) | BCP (ng of C g−1/h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Surface | Untreated | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.4 | 36.5 ± 0.3 | 25.6 ± 4.6 | 154.1 ± 8.6 |

| After nutrient supply | 9.7 ± 3.8 | 7 ± 1.1 | 137.5 ± 28.7 | 78.3 ± 12.5 | 65.3 ± 3.6 | ||

| Sand | Subsurface | Untreated | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 16.4 ± 1.8 | 14.6 ± 2.0 | 55.7 ± 10.8 |

| Mud | Surface | Untreated | 53.1 ± 16.0 | 46.3 ± 11.1 | 533.8 ± 157.3 | 497.6 ± 121.3 | 177.4 ± 65.5 |

| After nutrient supply | 24.1 ± 9.6 | 20.4 ± 8.6 | 342.4 ± 84.1 | 231.6 ± 101.8 | 79.8 ± 12.3 | ||

| Mud | Subsurface | Untreated | 46.1 ± 14.6 | 42.9 ± 15.4 | 450.6 ± 137.8 | 443.4 ± 151.1 | 425.4 ± 78.1 |

Reported are mean values with standard deviations.

AODC ranged between (1.5 ± 0.2) × 108 cells g−1 and (53.1 ± 16.0) × 108 cells g−1 (dry weight) in sandy and muddy sediments, respectively (Table 1). The surface layers of the sediments always displayed higher bacterial counts than did the subsurface suboxic sediment layers. Values of total bacterial abundance were within the range of those reported in most coastal marine sediments (28).

Estimates of the live and dead bacterial fractions in marine sediments.

LBC accounted for 26 to 30% of total bacterial counts (Table 2). Therefore, dead cells (i.e., those possessing damaged membranes) represented the most important fraction (70 to 74%) of bacterial assemblages in all samples analyzed. These findings are, to our knowledge, the first available for aquatic sediments and indicate that total counts of benthic bacteria include a largely dominant fraction of dead (damaged) cells. The fraction of live bacteria observed in this study was two or three times lower than the values reported in most studies on marine and freshwater systems (LBC, 50 to 70% of total counts [12, 38]). The LBC contribution to total bacterial count was rather constant among grain size types and layers of the sediment core.

TABLE 2.

Contribution of DVCs and counts of LBC, dead bacterial cells (DBC), NuCC, and RBC to total bacterial counts (AODC)f

| Sediment type | Layer | Treatment | LBCa (%) | DBCb (%) | NuCC (%) | DVCc (%) | DVCd (%) | RBCe (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sand | Surface | Untreated | 28.7 ± 2.6 | 71.3 ± 2.6 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 11.3 |

| After nutrient supply | 16.2 ± 2.3 | 83.8 ± 2.3 | 12.8 ± 5.7 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Sand | Subsurface | Untreated | 30.2 ± 1.7 | 69.8 ± 1.7 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | ND |

| Mud | Surface | Untreated | 26.0 ± 6.3 | 74.0 ± 6.3 | 3.8 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 1.5 | 5.8 |

| After nutrient supply | 15.4 ± 3.1 | 84.6 ± 3.1 | 9.6 ± 1.7 | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Mud | Subsurface | Untreated | 28.6 ± 0.4 | 71.3 ± 0.4 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 1.2 | ND | ND |

Cells possessing an integer membrane and not stained by PI.

Cells stained by PI.

Number of antibiotic cocktail-responsive cells after 8 h of incubation.

Number of antibiotic cocktail-responsive cells after 24 h of incubation.

Dormant bacteria inducible to an active state (dormant-reactivated bacteria).

Reported are mean values with standard deviations.

ND, not determined.

The comparison of LBC counts (i.e., both active and dormant bacteria) and the number of NuCC (which are assumed to represent only the actively growing bacterial fraction) revealed that LBC counts were 5 to 19 times higher than NuCC counts. The fraction of bacteria without a visible nucleoid (i.e., dormant or inactive) indeed accounted for 78 to 95% of bacteria possessing intact membranes and cell walls (LBC). Therefore, we calculated, for the difference between LBC and NuCC with respect to AODC, that 22 to 27% of total counts were accounted for by dormant bacteria.

Comparison between counts of NuCC and DVCs.

While a large body of information is available on NuCC counts in pelagic environments, data on NuCC relevance in marine sediments are completely lacking. Our findings (obtained from samples fixed with formalin) indicate that the number of NuCC in marine sediments is very low (range, 0.04 × 108 to 0.91 × 108 cells g−1) and accounted only for 1.5 to 6.2% of the total bacterial number (both mean and median values = 3.9% [Table 2]). This value is striking compared to values reported in the water column, where NuCC account on average for 30.1%, with a median value of 24.5% of total bacterial counts (calculated from data reported in references 3, 5, 12, 14, 18, 35, and 39). We tested the efficiency of the NuCC restaining protocol and found total counts identical to those obtained from AODC; therefore, the low number of NuCC in marine sediments is not the result of protocol or staining bias.

NuCC counts on sediment samples fixed with formalin were always significantly higher than those obtained on samples fixed using NaN3 (t test, P = 0.015). We therefore conclude that the use of NaN3 should be avoided when investigating marine sediments.

The percentage of NuCC in subsurface sediments was always higher than values reported in surface sediments (two times in muds and three times in sands). This result is consistent with other findings, based on 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyltetrazolium chloride (CTC) determinations, which revealed higher CTC-positive bacterial fractions in anoxic than in oxic sediments (28, 34). Therefore, our estimates are not the result of an artifact of sample preparation and suggest that increasingly reducing favorable conditions (i.e., lowering Eh values) did not affect NuCC abundance. Conversely, the fraction of NuCC increased with increasing nutrient concentrations in the sediment. Surface and subsurface muds, indeed, displayed total organic matter, chlorophyll a, and protein contents 8 to 15 times higher than did their sandy counterparts, and this resulted in a two- or threefold increase of the NuCC fraction.

The presence of bacteria responsive to antibiotic treatment (DVC) was clearly detectable after 8 h of incubation and further increased after 24 h, but the DVC fraction was rather variable (Table 2). As for NuCC counts, organically rich muds displayed higher percentages of DVC (4.8% of the total bacterial number) than did sandy sediments (0.3%). These results are 1 or 2 orders of magnitude lower than those reported so far in aquatic environments (generally ranging from 10 to >50% [16, 21, 38]). In agreement with previous studies on freshwaters (24), NuCC counts were always significantly higher (t test, P < 0.01) than were results for DVC. Such a difference could be explained with the low efficiency of the DVC protocol in identifying actively growing benthic bacteria, and caution must be used when comparing values obtained from water column and sediment samples, since the sediment matrix might reduce the effect of antibiotics on benthic bacteria. Therefore, further studies are needed to test the reliability of antibiotic treatment in marine sediments.

Experimental induction of dormant bacteria to an active metabolic state.

The NuCC abundance always increased significantly (t test, P < 0.01) after experimental nutrient enrichment, and such an effect, when expressed as a percentage, was three times more evident in sands than in muds (Table 2). This occurred even though, after substrate enrichment, the total bacterial number increased three times in sands while decreasing in muds (Table 1). Benthic bacteria often need a longer time to produce a positive response, and the decreased bacterial abundance and biomass production in mud sediments immediately after nutrient supplementing have already been reported (4). However, the reasons are unclear; one possibility could be that nutrient addition modified sediment physicochemical conditions (including oxygen levels), thus modifying bacterial metabolism.

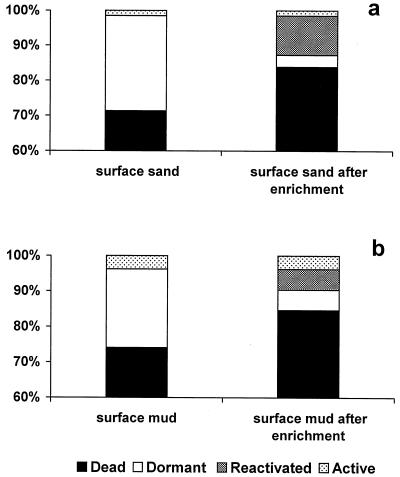

The fraction of dormant bacteria “reactivated” after nutrient enrichment (RBC) was calculated as the difference between NuCC before and after the 4-day experiment of nutrient enrichment. RBC constituted 6 and 11% of the total bacterial number in muds and sands, respectively. This means that 26 and 42% of dormant bacteria (in muds and sands, respectively) were “reactivated” by nutrient enrichment. Similar results have been reported after 4-day protein-enriched incubations in seawater mesocosms (26). Other studies reported a 20- to 40-fold increase in electron transport system-active bacterioplankton, after supplying of nutrients, from the amount found in untreated samples (6).

Estimates of the actual bacterial turnover rates in marine sediments.

In this work we investigated the physiological features of benthic bacteria to identify the fraction actively contributing to bacterial carbon production in coastal marine sediments and to define possible environmental constraints controlling the relevance of living and/or active benthic bacteria. Synthesizing our results, we demonstrated that benthic bacterial assemblages contain a large fraction of dead (ca. 70%) and dormant cells (ca. 25%). Therefore, the truly active bacterial fraction in the investigated sediments accounted only for less than 5% (Fig. 1). After organic enrichment we observed a change in the relative importance of the different bacterial components, as evident from the clear increase (6 to 11%) of the active bacterial fraction. Benthic bacteria from sands and muds displayed similar characteristics and live and dead bacterial fractions, but their response to nutrient input was more evident in sands than in muds, probably as a result of the oligotrophy of sandy sediments.

FIG. 1.

Relative contribution of dead, dormant, reactivated, and active bacteria before and after nutrient enrichment in sandy sediments (a) and muddy sediments (b).

Bacterial C production was higher in muddy than in sandy sediments, with median values of 301.4 ± 87.7 and 104.9 ± 34.8 ng of C g−1 h−1, respectively (Table 1). We estimated bacterial turnover rates (as the ratio of bacterial C production to bacterial biomass) by considering the total bacterial biomass, the LBC biomass, and the NuCC biomass (Table 3). Bacterial turnover rates calculated on total bacterial biomass (i.e., including dead and dormant cells) ranged from 0.01 to 0.1 day−1. Turnover rates were, on average, eight times higher if only the living biomass was considered and 50 to 80 times higher if only the biomass of active bacteria (NuCC) was taken into account. According to our estimates, the turnover of the active fraction of benthic bacteria ranged from 0.47 to 6.89 day−1, with an average doubling time of 3.24 day−1. These values are higher than turnover rates reported for the active fraction of bacterioplankton (0.2 to 2.4 day−1 [26, 39]). However, the experiment of nutrient enrichment that we carried out in marine sediments lowered bacterial turnover rates. This is in contrast with results obtained in the water column experiment, in which turnover rates increased after nutrient enrichment (13). This result could indicate also that benthic bacteria adjust their growth rates in response to changes in nutrient supply. Our findings suggest that the actual turnover rate of bacteria in marine sediments can be estimated on the basis of the number of NuCC and that actual turnover rates are at least 1 order of magnitude higher than those calculated on the basis of total bacterial counts.

TABLE 3.

Bacterial turnover rates (as ratio of bacterial C production to bacterial biomass)a

| Sediment type | Layer | Treatment | Ratio of bacterial C production to biomass (day−1)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total biomass | Living biomass | Active biomass | |||

| Sand | Surface | Untreated | 0.10 | 0.52 | 6.89 |

| After nutrient supply | 0.01 | 0.14 | 0.09 | ||

| Sand | Subsurface | Untreated | 0.08 | 0.34 | 3.80 |

| Mud | Surface | Untreated | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.47 |

| After nutrient supply | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.07 | ||

| Mud | Subsurface | Untreated | 0.02 | 0.10 | 1.80 |

Reported are values based on total bacterial biomass, LBC biomass, and active bacterial (NuCC) biomass.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by MIUR and by EU Project MEDVEG.

We are grateful to Antonio Dell'Anno for suggestions on the early draft of the manuscript and to Francesca Biavasco for helpful discussion of antibiotic treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R. I., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbesti, S., S. Citterio, M. Labra, M. D. Baroni, M. G. Neri, and S. Sgorbati. 2000. Two and three-colour fluorescence flow cytometric analysis of immunoidentified viable bacteria. Cytometry 40:214-218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bermann, T., B. Kaplan, S. Chava, Y. Viner, B. F. Sherr, and E. B. Sherr. 2001. Metabolically active bacteria in Lake Kinneret. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23:213-224. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boetius, A., and K. Lochte. 1996. Effect of organic enrichment on hydrolytic potentials and growth of bacteria in deep-sea sediments. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 140:239-250. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi, J. W., E. B. Sherr, and B. F. Sherr. 1996. Relation between presence-absence of a visible nucleoid and metabolic activity in bacterioplankton cells. Limnol. Oceanogr. 41:1161-1168. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi, J. W., B. F. Sherr, and E. B. Sherr. 1999. Dead or alive? A large fraction of ETS-inactive marine bacterioplankton cells, as assessed by reduction of CTC, can become ETS-active with incubation and substrate addition. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 18:105-115. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danovaro, R., E. Manini, and A. Dell'Anno. 2002. Higher abundance of bacteria than of viruses in deep Mediterranean sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1468-1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Giorgio, P. A., Y. T. Prairie, and D. F. Bird. 1997. Coupling between rates of bacterial production and the abundance of metabolically active bacteria in lakes, enumerated using CTC reduction and flow cytometry. Microb. Ecol. 34:144-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas, D. J., J. A. Novitsky, and R. O. Fournier. 1987. Microautoradiography-based enumeration of bacteria with estimates of thymidine-specific growth and production rates. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 36:91-99. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fry, J. C. 1988. Determination of biomass, p. 27-72. In B. Austin (ed.), Methods in aquatic bacteriology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 11.Gasol, J. M., P. A. delGiorgio, R. Massana, and C. M. Duarte. 1995. Active versus inactive bacteria: size dependence in a coastal marine plankton community. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 128:91-97. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasol, J. M., U. L. Zweifel, F. Peters, J. A. Fuhrman, and Å. Hagström. 1999. Significance of size and nucleic acid content heterogeneity as measured by flow cytometry in natural planktonic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:4475-4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hagström, Å., J. Pinhassi, and U. L. Zweifel. 2001. Marine bacterioplankton show burst rapid growth induced by substrate shifts. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 24:109-115. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heissenberger, A., G. G. Leppard, and G. J. Herndl. 1996. Relationship between the intracellular integrity and the morphology of the capsular envelope in attached and free-living marine bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4521-4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hobbie, J. E., R. J. Daley, and S. Jasper. 1977. The use of Nuclepore filters for counting bacteria by fluorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 33:1225-1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joux, F., and P. LeBaron. 1997. Ecological implications of an improved direct viable count method for aquatic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3643-3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karl, D. M., and J. A. Novitsky. 1988. Dynamics of microbial growth in surface layers of a coastal marine sediment ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 50:169-176. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karner, M., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1997. Determination of active marine bacterioplankton: a comparison of universal 16S rRNA probes, autoradiography, and nucleoid staining. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:1208-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kepner, R. L., Jr., and J. R. Pratt. 1994. Use of fluorochromes for direct enumeration of total bacteria in environmental samples: past and present. Microbiol. Rev. 58:603-615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kogure, K., U. Simidu, and N. Taga. 1979. A tentative direct microscopic method for counting living marine bacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 25:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kogure, K., U. Simidu, N. Taga, and R. R. Colwell. 1987. Correlation of direct viable counts with heterotrophic activity for marine bacteria. Appl. Environm. Microbiol. 53:2232-2237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBaron, P., P. Servais, H. Agogué, C. Courties, and F. Joux. 2001. Does the high nucleic acid content of individual bacterial cells allow us to discriminate between active cells and inactive cells in aquatic systems? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1775-1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McFeters, G. A., F. P. Yu, B. H. Pyle, and P. S. Stewart. 1999. Physiological assessment of bacteria using fluorochromes. J. Microbiol. Methods 21:1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muela, A., I. Arana, J. I. Justo, C. Seco, and I. Barcina. 1999. Changes in DNA content and cellular death during a starvation-survival process of Escherichia coli in river water. Microb. Ecol. 37:62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noble, R. T., and J. A. Fuhrman. 1998. Use of SYBR Green I for rapid epifluorescence counts of marine viruses and bacteria. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 14:113-118. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinhassi, J., F. Azam, J. Hemphala, R. A. Long, J. Martinez, U. L. Zweifel, and A. Hagstrom. 1999. Coupling between bacterioplankton species composition, population dynamics, and organic matter degradation. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 17:13-26. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter, K. G., and Y. S. Feig. 1980. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora. Limnol. Oceanogr. 25:943-948. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Proctor, L. M., and A. C. Souza. 2001. Method for enumeration of 5-cyano-2,3-ditolyl tetrazolium chloride (CTC)-active cells and cell-specific CTC activity of benthic bacteria in riverine, estuarine and coastal sediments. J. Microbiol. Methods 43:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez, G. G., D. Phipps, K. Ishiguro, and H. F. Ridgway. 1992. Use of a fluorescent redox probe for direct visualization of actively respiring bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:1801-1808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherr, B. F., P. delGiorgio, and E. B. Sherr. 1999. Estimating abundance and single-cell characteristics of respiring bacteria via the redox dye CTC. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 18:117-131. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson, L. H. 1978. A case for bacterial dormancy in aquatic systems. Microb. Ecol. 4:127-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabor, P. S., and R. A. Neihof. 1982. Improved method for determination of respiring individual microorganisms in natural waters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:1249-1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Duyl, F. C., B. de Winder, A. J. Kop, and U. Wollenzien. 1999. Tidal coupling between carbohydrate concentrations and bacterial activities in diatom inhabited intertidal mudflats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 191:19-32. [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Duyl, F. C., and A. J. Kop. 1994. Bacterial variation in North Sea sediments: clues to seasonal and spatial variations. Mar. Biol. 120:323-337. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vosjan, J. H., and G. J. van Noort. 1998. Enumerating nucleoid-visible marine bacterioplankton: bacterial abundance determined after storage of formalin fixed samples agrees with isopropanol rinsing method. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 14:149-154. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weinbauer, M. G., C. Beckmann, and M. G. Hofle. 1998. Utility of green fluorescent nucleic acid dies and aluminum oxide membrane filters for rapid epifluorescence enumeration of soil and sediment bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:5000-5003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams, S. C., Y. Hong, D. C. A. Danavall, M. H. Howard-Jones, D. Gibson, M. E. Frisher, and P. G. Verity. 1998. Distinguishing between living and non- living bacteria: evaluation of the vital stain propidium iodide and its combined use with molecular probes in aquatic samples. J. Microbiol. Methods. 32:225-236. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yokomanu, D., N. Yamaguchi, and M. Nasu. 2000. Improved direct viable count procedure for quantitative estimation of bacterial viability in freshwater environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5544-5548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zweifel, U. L., and Å. Hagström. 1995. Total counts of marine bacteria include a large fraction of non-nucleoid-containing bacteria (ghosts). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2180-2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]