Abstract

Cancer remains one of the most formidable diseases affecting human health, particularly because it involves complex reprogramming of metabolic pathways, especially pathways involved in lipid metabolism. Ether lipids (ELs), which alter membrane fluidity and signaling pathways that promote tumor initiation and development, have emerged as important regulators of cancer biology, positioning them as emerging candidate targets for diagnosis and treatment. The main focus of this review is the metabolic dysregulation of ELs in tumors, particularly the metabolic, genetic, and epigenetic processes that promote invasion, proliferation, and drug resistance. This review highlights preclinical treatment strategies designed to target EL synthases, aiming to provide novel perspectives for future translational applications that support more sustainable therapeutic options. In addition to future prospects centered on standardized detection and multiomics integration to improve precision oncology, important hurdles, including tissue specificity and metabolic heterogeneity, are covered.

Keywords: Ether lipids, Neoplasms, Metabolism, Therapeutics, Biomarkers

Introduction

In contemporary medical research, cancer represents one of the most daunting challenges to human health. Compared with normal cells, tumor cells exhibit notable heterogeneity, especially with respect to their biological function and regulation of gene expression. Metabolic reprogramming, in which tumor cells alter their metabolic pathways to facilitate rapid growth and survival under stress, is a characteristic of cancer [1]. The main changes caused by this reprogramming are the metabolism of glutamine, lipids, and glucose [2]. Lipid metabolism is essential for metabolic reprogramming and is crucial for the development, spread, and metastasis of cancer [2]. The gene ACSL4, which is linked to the production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), promotes the vascular extravasation of tumor cells [3]. Increased PUFA levels promote tumor cell spread by strengthening the β-oxidation pathway. On the other hand, other studies have indicated that elevated PUFA levels can cause tumor cells to undergo ferroptosis, which prevents the growth of cancer and decreases the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [4]. The importance of thoroughly investigating the regulatory mechanisms of lipid metabolism in tumor cells is underscored by its dual role in cancer. These studies are essential for improving our knowledge of the biology of cancer and for developing focused treatment plans.

Unlike the ester bond that connects the carbon chain, ether lipids (ELs) are a unique class of lipids that are distinguished by the presence of an ether bond at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone [5]. Research has shown that ELs are essential for regulating the shape and function of membrane receptors, including growth factor receptors and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Consequently, ELs play active roles in differentiation and cellular signal transduction processes [6]. Furthermore, by scavenging free radicals and regulating the activity of antioxidant enzymes, ELs have strong antioxidant properties that support cellular redox homeostasis [7]. In addition to shielding cells from oxidative damage, this antioxidant activity is essential for controlling ferroptosis [8]. ELs are highly abundant in the immune system, heart, and brain, and play roles in membrane fluidity, shape, and the control of membrane-associated signaling. The serious repercussions of their shortage highlight the importance of different EL types in human health. Hereditary peroxisome disorders, which frequently present as severe developmental abnormalities such as neurological impairments and a loss of vision and hearing, can be caused by a deficiency of these lipids [5]. Snyder and Wood [9] originally reported that rat and human malignancies present higher levels of ELs than normal tissues as early as the late 1960s. In the decades that followed, a notable increase in the EL content was verified in a variety of primary tumors, and this increase was directly linked to the biological activity of tumor cells. According to an increasing number of studies, EELs are essential for tumor growth, apoptosis, ferroptosis, migration, metastasis, angiogenesis, and the tumor microenvironment (TME). As a result, ELs are becoming recognized as crucial molecules for maintaining cellular integrity and signaling in cancer.

Although previous studies have focused mainly on the roles of ELs in noncancer disorders [10], recent findings highlight their emerging importance in oncology. We hypothesize that ELs act not only as structural and metabolic components but also as crucial regulators of ferroptosis and the immune microenvironment. The novelty of this review lies in integrating these diverse functions with therapeutic perspectives, thereby advancing beyond previous work. We first delineate the taxonomy and biological roles of ELs and then discuss their regulation and effects on tumor progression and the TME. Finally, we examine therapeutic approaches targeting ELs, providing a comprehensive view spanning from basic ideas to practical implementations.

Classification of ELs

ELs are a specialized class of glycerophospholipids that are synthesized in peroxisomes. Unlike the more common diacylglycerol lipids, which use an ester bond, these lipids have an ether bond connecting the hydrocarbon chain at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone. This seemingly insignificant metabolic difference has important structural and functional implications. In model membranes, ELs frequently form nonlayered hexagonal structures, suggesting that ELs may promote membrane fusion [5].

Structural characteristics

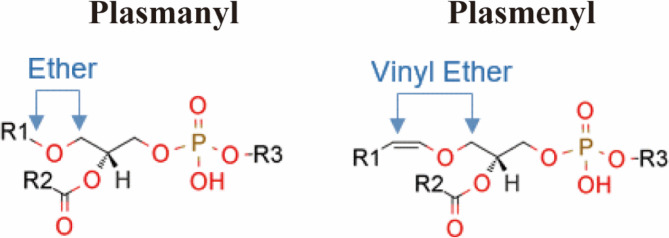

ELs have three main kinds of substituents at the sn-1 position: acyl groups, alkyl groups, and alkenyl groups [11]. The most prevalent ELs are plasmanyl lipids and plasmenyl lipids, and Fig. 1 summarizes the relevant research. Plasmanyl lipids (1-O-alkyl ELs) are a subclass of ELs characterized by a saturated or monounsaturated alkyl ether linkage at the sn-1 position, an esterified fatty acid at the sn-2 position, and a phosphate-containing head group, such as choline or ethanolamine, at the sn-3 position. C16:0, C18:0, or C18:1 are the possible fatty acid chains connected by the ether bond at the sn-1 position [12]. Another subclass of ether phospholipids (ePLs) is plasmenyl lipids (1-O-alk-1’-enyl ELs, also known as plasmalogens), which are identified by a vinyl-ether bond at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone. Because of these unique structural characteristics, plasmalogens have unique biochemical and functional characteristics, making them the most common type of ELs [5].

Fig. 1.

General structures of plasmanyl and plasmenyl phospholipid species. Plasmanyl phospholipids contain an ether bond at the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone with a saturated or monounsaturated alkyl chain, whereas plasmenyl phospholipids (also called plasmalogens) are characterized by a vinyl-ether bond at the sn-1 position. Both subtypes typically contain an ester-linked fatty acid at the sn-2 position and a polar head group (such as phosphoethanolamine or phosphocholine) at the sn-3 position. (Source: PMID: 28263877)

Functional diversity in ELs

Due to the vinyl-ether bond at the sn-1 position and enrichment of PUFAs at the sn-2 position, plasmalogens are particularly susceptible to lipid peroxidation and are linked to the promotion of ferroptosis [13]. They react readily with reactive oxygen species (ROS), exerting protective effects on oxidative damage [14]. In the nervous system, ELs play essential roles in myelination and synaptic function, whereas in immune cells, they modulate key processes such as phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine signaling. Furthermore, plasmalogens inhibit TLR4 endocytosis, leading to a reduction in inflammatory signaling mediated by NF-κB and p38 MAPK [15]. Additionally, plasmalogens may regulate natural killer (NK) cell activity through interactions with orphan GPCRs [16].

Among the various subtypes of ELs, plasmanyl lipids can activate the phospholipase C/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate/diacylglycerol signaling cascade via engagement with the PAF receptor [17], which may increase cancer cell proliferation and motility. In general, various cancer cells exhibit elevated levels of plasmanyl lipids, which promote tumor invasion and metastasis by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [18]. Moreover, metabolic derivatives of plasmanyl lipids may stimulate lysophosphatidic acid receptors, further facilitating cancer progression [17]. Notably, in neural tissues, plasmanyl lipids chiefly modulate inflammatory signaling, underscoring their context-dependent functional diversity. Unlike plasmalogens, plasmanyl lipids demonstrate greater oxidation resistance, allowing them to protect cells from ferroptosis under stress conditions [19]. This biochemical divergence emphasizes their seemingly contradictory roles in cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Differences between plasmalogens and plasmanyl lipids

| Feature | Plasmalogens | Plasmanyl Lipids |

|---|---|---|

| Ether Bond Type | Vinyl-ether bond at sn-1 position | Alkyl-ether bond (saturated) at sn-1 position |

| Stability | Less stable, prone to oxidation due to vinyl bond | More stable under oxidative conditions |

| Major Functions | Antioxidant role, membrane fluidity, signal transduction | Membrane structure, signaling (PAF pathway) |

| Susceptibility to ROS | High | Low |

| Notable Metabolites | PUFA-ePE | PAF, LPA precursors |

PUFA-ePE PUFA-ether phosphatidylethanolamine, PAF Platelet-activating factor, LPA Lysophosphatidic acid

However, the functions of unsaturated fatty acids and PUFAs differ significantly. For instance, monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA)-containing ether phosphatidylcholines are linked to therapeutic resistance, preservation of the redox balance, and membrane stability in aggressive tumors such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, whereas PUFA-enriched ether phosphatidylethanolamines sensitize cells to ferroptosis by acting as substrates for lipid peroxidation.

When considered collectively, the functional diversity of ELs emphasizes the need for further study of lipid species at the molecular level instead of classifying them into a single group. Accurately interpreting the experimental results and creating focused interventions that exploit lipid metabolism in cancer require the ability to distinguish between plasmalogens and plasmanyl lipids, as well as PUFA- and MUFA-enriched species.

Regulatory mechanisms of ELs in cancer

EL biosynthesis is a compartmentalized process that is initiated in the peroxisome and completed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). This process begins with the acylation of dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) by glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT). This step is followed by the substitution of the acyl group with a fatty alcohol, facilitated by alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS), leading to the formation of an ether bond. Fatty alcohols are supplied by fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1/2 (FAR1/2). The resulting alkyl-DHAPs undergo reduction and are translocated to the ER, where they are further modified to produce mature ELs, including plasmalogens and alkenylacylglycerols. The key steps in this biosynthetic pathway include acylation, head group attachment, and desaturation by TMEM189 (Fig. 2). ELs are vital components of cellular membranes and ensure structural integrity while contributing to various metabolic functions. In the context of cancer, their levels are regulated by complex and often aberrant mechanisms. The subsequent subsections explore the diverse regulatory pathways that influence EL levels in cancer cells, emphasizing the importance of understanding these processes for developing innovative cancer therapies.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of EL levels. EL biosynthesis is initiated in peroxisomes, in which dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) is produced from glycerin. Key enzymes include glyceronephosphate O-acyltransferase (GNPAT), fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1 (FAR1), and alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS), which generate critical intermediates such as 1-alkyl-DHAP and 1-acyl-DHAP. The pathway continues in the endoplasmic reticulum to produce mature ether phospholipids. Regulatory factors such as hypoxia-inducible factor-2α (HIF-2α) and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) modulate peroxisomal metabolism under hypoxic conditions, thereby altering EL synthesis. THEM6, MS4A15 and extracellular lipids further contribute to fine-tuning EL levels

Key enzyme-mediated regulation

ELs play crucial roles in lipid droplet (LD) biogenesis and dynamics and are regulated by AGPS, which is being increasingly recognized as a key player in cancer metabolism. AGPS-derived ELs are believed to modify the membrane curvature and packing properties, thereby facilitating the budding of LDs from the ER. An interaction between AGPS and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K (HNRNPK) has been observed, suggesting that a noncanonical AGPS–HNRNPK axis is involved in LD biogenesis [20]. This axis is proposed to integrate lipid biosynthesis with transcriptional control, promoting LD accumulation to meet the heightened lipid demand of cancer cells. AGPS is overexpressed in many cancers, and its abnormal regulation significantly affects tumor development and progression [21], Notably, AGPS knockdown could lead to a reduction in cellular EL levels [22]. Zhang et al. [23] reported that AGPS can be ubiquitinated and degraded by the E3 ligase mouse double minute 2 (MDM2) through the proteasomal pathway, with the kinase TrkA promoting the interaction between AGPS and MDM2 by phosphorylating AGPS at the Y451 site. Additionally, modulating the supply of fatty alcohols in cancer cells may influence EL levels, similar to the effect of controlling AGPS expression. Helicobacter pylori, which is linked to nearly all gastric cancers in Asia [24], has a known cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) that increases AGPS expression by activating the MEK/ERK/SRF pathway [25]. These findings are consistent with the broader understanding that alterations in EL metabolism can significantly affect cancer cell behavior, as observed in multiple studies on the role of ELs [21].

GNPAT and FAR1 are also critical enzymes involved in EL synthesis whose dysregulation disrupts normal processes, thereby affecting overall EL levels in cancer cells. Salame et al. [22] reported that the loss of GNPAT results in a significant 60%–80% reduction in cellular EL levels, notably ether glycerophospholipids and ether triglycerides. Through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockdown of FAR1, researchers found that the deletion of FAR1 could lead to a substantial decrease in the levels of ELs, particularly polyunsaturated ether phospholipids (PUFA-ePLs), in cells [26].

In addition, certain proteins directly regulate EL levels in cancer cells. In prostate cancer, the THEM6 protein has been identified as a key regulator. High THEM6 expression is linked to treatment resistance, while its deletion leads to a reduction in intracellular EL levels. This finding is crucial because THEM6 essentially influences both tumor growth and the response to androgen-deprivation therapy, highlighting the significance of THEM6-mediated EL regulation [27]. In cancer cells, MS4A15 is localized to the ER and drives ferroptosis resistance through calcium-restricted lipid remodeling. It reprograms membrane phospholipids, leading to an increase in the levels of shorter, more saturated ELs [28]. These examples illustrate how different proteins exert distinct effects on EL levels and cancer-related processes.

Tumor environment-mediated regulation

Peroxisomes play a crucial role in lipid metabolism, with their functions being closely tied to the availability of molecular oxygen. In the presence of hypoxic conditions, hypoxia-inducible factor alpha (Hif-2α) becomes stabilized, which induces peroxisomal autophagy while simultaneously inhibiting PPARα-mediated peroxisome proliferation. This dual mechanism results in a substantial reduction in the EL synthesis capacity, ultimately leading to decreased levels of ELs [29]. Additionally, the lipid immunogen CaLGL-1, produced by Collinsella aerofaciens, activates Toll-like receptor 2, generating proinflammatory cytokines [30]. This interaction may have implications for modulating the TME and increasing the efficacy of cancer treatments. Furthermore, the extracellular lipid environment plays a vital role in regulating EL levels in cancer cells. These studies indicate that the levels of certain ELs increase in lipid-starved cancer cells.

Reprogramming of EL metabolism

Cancer cells are characterized mainly by significant metabolic reprogramming, with EL metabolism intricately linked to fatty acid metabolism. Enzymes involved in EL metabolism, such as alkylglycerol monooxygenase (AGMO) and AGPS, strongly influence the levels of fatty acids. Modulating AGMO activity could lead to either the accumulation or depletion of specific fatty acids or their derivatives [31]. Defects in genes related to EL metabolism result in a decrease in EL synthesis. The body compensates for this reduction by altering other lipid metabolic pathways, thereby triggering lipid metabolic reprogramming [32].

The connection between EL metabolism and glycolysis is critically important in cancer cells. The intermediate product of DHAP in glycolysis is converted to glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P), a key substrate for EL synthesis [5]. The upregulation of glycolysis facilitates a greater supply of G3P, which fuels the peroxisomal acyl-DHAP pathway for EL production. Consequently, increased availability of G3P contributes to the increased synthesis of ELs, influencing membrane properties, signal transduction, and, ultimately, the survival and proliferation of cancer cells [33].

In summary, the regulation of EL levels in cancer is a highly complex and dynamic process influenced by multiple interconnected factors. These factors include enzyme-mediated regulation, gene interactions, tumor microenvironmental influences, and other metabolic conditions, all of which contribute to the complex lipid metabolic landscape within cancer cells. Accumulating evidence suggests that aberrant EL levels serve not only as biomarkers of cancer progression but also as key determinants of the treatment response.

The role of ELs in cancer progression

ELs play crucial roles in both determining the membrane structure and the formation of lipid rafts, which facilitate cancer progression. By modulating various pathways and molecules, ELs can promote the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells while also inducing programmed tumor cell death and remodeling the TME. These interactions are summarized in Table 2; Fig. 3.

Table 2.

The role of ELs in cancer progression

| Role | Cancer type | Mechanisms | Key Components | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proliferation promotion | Breast and melanoma | AGPS | LPA, eicosanoids | [34] |

| Colorectal | Selenoi | ePE | [35] | |

| Lung | FASN | PUFA-ePLs | [36] | |

| Kidney and ovarian | Peroxisome | PUFA-ePLs | [26] | |

| Apoptosis and ferroptosis regulation | Kidney and ovarian | TMEM164 | C20:4-ePLs | [37] |

| Colorectal | AGPS | PUFA-ePLs | [38] | |

| Leukemia | CD95 | Edelfosine | [39] | |

| Sarcoma | ROS | DGLA | [40] | |

| Invasion and metastasis promotion | Breast and prostate | SK3 channel | PUFA-ePLs | [41] |

| Breast | PI3K/Akt | AD-HGPC | [42] | |

| Kidney | SK3 channel | Ohmline | [43] | |

| Lung | Peroxisome | ePC and ePE | [44] | |

| TME reinvention | Leukemia | Macrophage | PUFA-ePLs | [31] |

| Colorectal | Macrophage | LPA | [45] |

LPA Lysophosphatidic acid, ePE Ether-phosphatidylethanolamine, DGLA Dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid, SK3 Small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel 3, AD-HGPC 2-Acetamido-2-Deoxy-l-O-Hexadecyl-rac-Glycero-3-PhosphatidylCholine, PC Phosphatidylcholine, LPC Lysophosphatidylcholin, PE Phosphatidylethanolamine, Selenoi Selenoprotein I, PUFAs Polyunsaturated fatty acids, AGMO Alkylglycerol monooxygenase, ROS Reactive oxygen species

Fig. 3.

Pathways and molecular mechanisms by which ELs contribute to cancer biology. ELs are regulated by alkylglycerone phosphate synthase (AGPS) and alkylglycerol monooxygenase (AGMO) to promote tumor cell proliferation and metastasis by activating the MMP9, SK3 channel, PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways. Fatty acid synthase (FASN), TMEM164 and selenoprotein I (Selenoi) affect ELs to increase programmed cell death, including apoptosis (via the modulation of Bcl-2 family proteins) and ferroptosis (through polyunsaturated ether phospholipids, PUFA-ePLs). Furthermore, ELs modulate the tumor immune microenvironment by influencing tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)

Promotion of proliferation

The upregulation of AGPS increases the synthesis of ELs that incorporate PUFAs, whereas selenoprotein I (Selenoi) is involved in EL production. The inhibition of AGPS decreases both EL and PUFA levels, ultimately affecting cell proliferation. Similarly, a deficiency in Selenoi disrupts EL synthesis, which can impair PUFA function and consequently influence tumor growth [46]. Notably, Selenoi is upregulated in colorectal cancer (CRC), and its deficiency is associated with impaired intestinal epithelial regeneration and reduced tumor growth. In aggressive tumors, AGPS is upregulated to increase EL levels, thereby promoting cell proliferation [47]. Furthermore, certain glycosylated antitumor ether lipids (GAELs) exert potent cancer-killing effects, indicating that disrupting EL-associated processes can compromise cell viability [48]. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, resistant cancer cells are enriched in MUFA-linked ELs. These lipids play pivotal roles in maintaining the redox balance and increasing cell survival under stress, potentially contributing to tumor proliferation and therapeutic resistance [49].

Abnormal activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is closely associated with the uncontrolled growth of tumor cells [50]. PI3K catalyzes the phosphorylation of PIP2 to form PIP3, leading to the activation of AKT. Activated AKT facilitates the full activation of mTORC2 while simultaneously phosphorylating mTORC1, which stimulates p70 S6 kinase activity and promotes processes linked to cancer cell growth and proliferation [51].

Promotion of invasion and metastasis

ELs play critical roles in cancer invasion and metastasis by influencing extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and the epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT), both of which are essential processes in tumor progression. In ECM remodeling, ELs have been shown to regulate the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP9, which is critical for ECM degradation and cancer cell invasion [41]. Studies suggest that inhibiting AGPS reduces MMP9 expression, thereby limiting ECM degradation and decreasing the invasive potential of cancer cells [41]. Additionally, EL metabolism is essentially associated with the regulation of SK3 channels, which are involved mainly in cancer cell migration and invasion [41]. Ion channels, which are modulated by ELs, are key regulators of the PI3K/Akt pathway and are known for their involvement in promoting the EMT [42]. By affecting these pathways, ELs may indirectly drive the EMT, thereby facilitating cancer cell dissemination [42].

In addition to their effects on ECM remodeling and the EMT, ELs also directly influence cancer cell migration. For example, the SK3 channel inhibitor ohmline has been shown to decrease cancer cell migration [43], emphasizing the importance of EL-related ion channel regulation. In breast cancer, AGPS is crucial for inducing SK3 expression through the regulation of miR-499 and miR-208 [41]. Silencing AGPS results in reduced SK3 expression, which subsequently leads to decreased SK3-dependent calcium entry, cell migration, and MMP9-mediated adhesion and invasion [41]. These observations highlight the close relationship between AGPS-mediated EL metabolism and tumor aggressiveness. Furthermore, potential biomarkers, including ELs, have been identified in malignant pleural effusions of lung cancer patients, indicating their possible role in cancer metastasis [44].

Regulation of apoptosis

EPLs represent a specific subtype of ELs that play a crucial role in cancer progression by modulating apoptosis, primarily through their regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins [21]. These proteins are central to controlling cell survival and include both pro-apoptotic (Bax and Bak) and antiapoptotic (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL) members. Certain ePLs can increase the expression or activity of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins, effectively preventing cytochrome C release from mitochondria and inhibiting caspase-dependent apoptosis [21]. Conversely, synthetic alkyl ELs such as edelfosine promote apoptosis, although their effects may be diminished by Bcl-2 overexpression, highlighting the complex interplay between EL metabolism and the regulation of apoptosis [52]. Furthermore, edelfosine and other alkyl ELs can accumulate in the ER and mitochondria of cancer cells, where defects in the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine induced by these lipids may trigger apoptosis and ER stress [52]. The synthesis of GAELs, which includes changes in glycosylation and lipid backbone, may also play a role in the regulation of apoptosis [53].

Regulation of ferroptosis

Emerging evidence links ePL metabolism to ferroptosis. For example, TMEM164 was identified as an acyltransferase that synthesizes C20:4 ePLs, and a genetic disruption of TMEM164 reduces C20:4 ePL levels, leading to variable protection from ferroptosis across cancer cell lines [21]. Since ferroptosis and apoptosis are interconnected, alterations in C20:4 ePL levels may also affect apoptosis-related proteins and the balance between pro- and antiapoptotic signaling. Moreover, polyunsaturated PUFA-ePLs are strongly associated with ferroptosis in cancer cells [26]. AGPS, a key enzyme involved in EL biosynthesis, regulates ePL levels and thereby contributes to ferroptosis susceptibility [38]. Studies using C. elegans and human cancer cells further indicate that endogenous ELs protect against ferroptotic cell death induced by dietary dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid (DGLA) [40]. This protective effect may be explained by their role as oxidative “sinks”, counteracting lipid ROS propagation, which could indirectly influence the apoptosis dynamics in cancer cells [40]. Together, these findings highlight that the synthesis and remodeling of ELs are part of a sophisticated metabolic network that involves the regulation of both apoptosis and ferroptosis [21].

Regulation of autophagy

The role of ELs in regulating autophagy is less well defined [54]. Some studies report that ELs can function as pro-survival signals by supporting autophagy, whereas others suggest that they act as pro-death mediators [55]. Additionally, reports on the ability of oxidized phospholipids to inadvertently increase autophagy and the metastatic potential reinforce the hypothesis that lipid modifications can drive divergent autophagic outcomes [56]. These discrepancies are likely due to differences in EL subclasses and experimental models, which could influence how ELs affect autophagic pathways. Additionally, the interconnected nature of lipid metabolism may lead to indirect effects on autophagy that are difficult to isolate. These inconsistencies underscore the need for more mechanistic investigations to clarify the context-dependent effects of ELs on autophagy in cancer biology.

Promotion of angiogenesis

ELs are significantly involved in angiogenesis, a crucial process that drives tumor growth and progression. Research on Peds1-deficient zebrafish has indicated that plasmalogens are vital for normal development and tissue regeneration [57]. Given the strong correlation between angiogenesis and tissue repair [58], plasmalogens may also contribute to tumor angiogenesis. The disruption of EL synthesis in β-cells may similarly be observed in endothelial cells during tumor angiogenesis, potentially influencing the formation and stability of new blood vessels [59]. Furthermore, investigations examining the cervicovaginal metabolome suggest a strong association between lipids and genital inflammation [60]. Alterations in peroxisome-related lipid metabolism could result in an imbalanced cellular microenvironment. Similar disruptions within the TME could promote inflammation, thereby inducing angiogenesis. ELs might play a role within this intricate regulatory framework [59].

Reinvention of TME

ELs profoundly influence the modulation of the TME, particularly tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Components such as tetrahydrobiopterin and AGMO can modify the lipidome of murine macrophages, subsequently influencing cytokine expression and signaling pathways in these cells and potentially regulating TAM activity. Variations in EL levels driven by AGMO could alter immune cell recruitment and TAM activation, ultimately influencing tumor growth and progression [61]. Additionally, ELs may affect peptide‒membrane interactions, which in turn could modify TAM behavior. This disruption essentially affects signaling pathways that regulate TAM activation, thus affecting tumor growth [62]. In CRC, lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) influences TAM polarization through lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1/3 (LPAR1/3), shifting it toward either the M1 (proinflammatory) or M2 (anti-inflammatory) state [45]. Furthermore, LPA inhibits CD8⁺ T-cell cytotoxicity and activation through GPCRs, blocking the formation of immune synapses [45]. Furthermore, LPA can induce the chemotaxis of human NK cells and trigger intracellular Ca²⁺ mobilization, suggesting that LPA receptors mediate NK cell migration/activation [63]. Although research on NK cells is not focused on cancer, the results provide direction for research on their roles in the TME.

Notably, ELs play complex roles in cancer progression by promoting cell proliferation, resistance to apoptosis and ferroptosis, and facilitating invasion, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Key enzymes such as AGPS and Selenoi regulate EL synthesis, affecting the redox balance and cell survival. Additionally, ELs remodel the TME by modulating immune cell populations, including TAMs and neutrophils, thereby influencing cytokine signaling and ER stress responses. Their involvement in the EMT, MMP activity, and vascular remodeling highlights their significant effects on tumor aggressiveness. These diverse functions position ELs as potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer.

ELs as targets for cancer treatments

Accumulating evidence indicates that some EL compounds are a new class of antitumor medicines, and they have also been shown to exert cytotoxic effects on leukemia [64]. Several mouse and rat models of cancers have been shown to respond to the therapeutic action of ELs in vivo. After a clinical phase I pilot trial was completed, the tumors in a subgroup of patients responded to treatment [65]. However, several obstacles need to be overcome at different stages in EL research. Improving their use in precision cancer diagnosis and treatment requires the standardization of research paradigms and encouraging interdisciplinary cooperation. Current research on targeted EL therapy focuses on inhibiting key synthetic enzymes, interfering with tumor lipid homeostasis, and combining it with other treatments. These treatment options have received good feedback in preliminary studies. Synthetic drugs based on EL structures and nanodelivery systems are being explored to improve anticancer efficacy and reduce toxicity. Although this research is still in the early stage, targeting EL metabolism has shown potential in cancer treatment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Research progress on ELs as targets for cancer treatment

| Targeting | Drugs | Phase | Cancer type | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGPS inhibitors | Larotrectinib | Clinical | Prostate cancer | Inhibits AGPS degradation | [23] |

| AGPS-IN-2i | Preclinical | Breast cancer | AGPS binder | [47] | |

| ZINC-69,435,460 | Preclinical | Melanoma, breast, ovarian cancer | AGPS binder; lowers EL levels EL | [66] | |

| EL metabolism | L-Rham | Preclinical | Ovarian cancer | Induces apoptosis-independent cell death | [67] |

| Edelfosine | Clinical (I/II) | Leukemia, solid tumors | Induces apoptosis | [68] | |

| Ilmofosine | Preclinical | Advanced solid tumors | Inhibits protein kinase C | [69] | |

| Perifosine | Clinical (I) | Leukemia, solid tumors | Induces apoptosis-independent cell death | [70] | |

| Combination therapies | Edelfosine + autophagy inhibitor | Preclinical | Pancreatic cancer | Enhances apoptosis; overcomes immunotherapy resistance | [71] |

AGPS Alkylglycerone phosphate synthase, EL Ether lipid

Inhibitors targeting EL synthases

ELs, particularly plasmalogens, have garnered considerable interest in cancer research because of their crucial roles in NK cell activation and the survival of lymphoma cells under oxidative stress [16]. Consequently, the inhibition of AGPS emerges as a promising strategy for reducing EL levels. An inhibitor of TrkA, larotrectinib, inhibited the degradation of AGPS via MDM2, thereby increasing the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to the peroxidase inhibitor ML210, which subsequently increased their lethality [23]. Additionally, AGPS inhibitors are being explored as potential therapeutic approaches that could impact eicosanoid-lysophospholipid synthesis, which is vital for cell signaling and lipid metabolism. AGPS inhibition also affects the biosynthesis of neutral ELs such as MADAG [72]. Furthermore, AGPS inhibition may disrupt plasmalogen-related pathways, including plasmalogen–GPCR21 signaling [16], potentially altering the TME. Changes in EL metabolism can also affect critical cancer-related enzymes, such as platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase [73]. Notably, some AGPS inhibitors have advanced to preclinical testing; for instance, AGPS-IN-2i has been shown to reduce ether phospholipid levels in breast cancer models by 50%−70% within 24 h, inhibit cell migration and the EMT, and suppress tumor cell proliferation in both breast and prostate cancer models [47]. Similarly, ZINC69435460 increases the sensitivity of cancer cells to ferroptosis, indicating that the suppression of EL synthesis may increase tumor cell vulnerability [66].

These inhibitors significantly reduce EL levels, impair cell proliferation, inhibit migration and the EMT, and increase sensitivity to ferroptosis. Despite the progress that has been achieved, the intricate nature of lipid metabolism presents substantial challenges for the development of AGPS inhibitors. The mevalonate pathway, which precedes cholesterol synthesis, is involved in the process through which intermediates that can influence ferroptosis are produced, while AGPS inhibition can disturb overall lipid homeostasis. Additionally, the transport and metabolism of ELs are affected by various factors, including the blood–brain barrier, which limits lipid entry and complicates drug delivery [74]. Overall, AGPS inhibition has the potential to disrupt multiple pathways that affect tumor immunity and cancer cell viability; however, the development of AGPS inhibitors is still in its infancy, with no clinically approved specific inhibitors available to date. Understanding the broader effects of AGPS inhibition on tumor immunity, inflammation, and lipid homeostasis is essential for optimizing treatment strategies.

Targeting EL metabolism and chemoresistance

Chemoresistance represents a major challenge in cancer treatment, highlighting the need to understand the role of EL metabolism in this context to develop more effective therapeutic strategies. Alterations in EL pathways seem to allow cancer cells to evade chemotherapy, positioning them as promising targets for overcoming drug resistance, including through GAELs. The GAEL compound L-Rham has been shown to effectively induce the death of high-grade serous ovarian cancer cells irrespective of their sensitivity to chemotherapy [75]. Unlike traditional chemotherapeutic agents, GAELs promote cell death through an apoptosis-independent mechanism, primarily involving cytoplasmic vesicle formation and endocytosis, thereby bypassing the apoptotic resistance mechanisms that commonly develop in cancer cells [75]. Araújo et al. [76] reported that the transition from hormone-dependent to hormone-independent tumors, which are resistant to treatment, is correlated with increased phospholipid levels associated with EL metabolism. These metabolic changes may increase cancer cell survival and proliferation, thereby facilitating resistance to endocrine therapies. Among GAELs, three compounds, namely, edelfosine, ilmofosine, and perifosine, have advanced to clinical research. As a prototypical synthetic EL, edelfosine induces apoptosis in both leukemic and solid tumor cells primarily through FAS/CD95 clustering within lipid rafts. It has been evaluated in phase I/II clinical trials, demonstrating a favorable safety profile and preliminary indications of tumor stabilization [68]. Ilmofosine underwent a phase I pharmacokinetic study in patients with advanced solid tumors, showing good tolerability along with an effective tissue distribution [69]. Perifosine, an alkyl phospholipid related to edelfosine, has therapeutic potential in various cancer types through its ability to disrupt AKT signaling and promote apoptosis [70].

In summary, certain EL analogs can help cells evade apoptosis and trigger alternative cell death pathways, presenting a strategic advantage against apoptosis-resistant tumors. Targeting EL metabolism provides a novel mechanistic approach to overcome this challenge. However, the exact molecular link between EL modulation and the reversal of chemoresistance remains only partially understood, particularly given the pleiotropic nature of ELs, which complicates target specificity and efficacy predictions. Furthermore, drug resistance mechanisms may diminish therapeutic effectiveness. Future clinical efforts should emphasize designing rational trials, developing biomarkers to monitor the therapeutic response, and elucidating EL-driven resistance mechanisms.

Combination therapy strategies

Combination therapies have emerged as promising strategies for cancer treatment by increasing treatment efficacy and overcoming drug resistance. Integrating EL-targeted therapy with other treatment modalities represents a cutting-edge approach, with numerous studies highlighting its potential. In pancreatic cancer, the EL compound edelfosine accumulates in the ER, triggering cellular stress and apoptosis, where autophagy often acts as a cytoprotective mechanism in cancer cells. By inhibiting autophagy, a combination strategy amplifies the tumor-killing effects of edelfosine, providing a novel avenue for treating pancreatic cancer, a disease that is notoriously resistant to conventional therapies. Innovative nanoparticle-based drug delivery also plays a crucial role in optimizing combination treatments [71]. Nanoarchaeosomes loaded with doxorubicin exhibit high drug loading efficiency and sustained release, ensuring effective drug delivery while minimizing side effects. Combining these nanocarriers with EL-targeted therapy could further improve the chemotherapeutic outcomes. Ferroptosis is closely linked to EL metabolism, and numerous investigations have suggested that CD8 + T cells activated by immunotherapy can promote ferroptosis by increasing lipid peroxidation, highlighting the potential synergy between immunotherapy and EL-targeted therapy, in which the induction of ferroptosis could promote cancer cell eradication.

Combining EL-targeted therapies with chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or ferroptosis inducers could produce synergistic effects, improving cancer cell killing and overcoming the limitations of monotherapies. However, such combination strategies may carry additive toxicity risks, particularly when multiple agents simultaneously influence lipid metabolism, mitochondrial function, or the immune system. Consequently, further research is needed to elucidate the mechanistic interactions between combined treatments, define optimal therapeutic windows, and assess resistance risks to guide the rational design of combination treatments, necessitating systematic testing in phase-specific trials.

Targeting EL metabolism represents a promising avenue for cancer therapy. Inhibitors of AGPS have shown potential for reducing lipid levels and inhibiting tumor growth, although challenges persist because of the complexity of lipid metabolism and limited clinical translation. EL pathways are also involved in chemoresistance, with compounds such as GAELs demonstrating apoptosis-independent cytotoxicity toward resistant cancer cells. Furthermore, combination therapies exert synergistic effects, particularly by promoting ferroptosis and increasing drug efficacy. Future research should prioritize overcoming delivery barriers and optimizing these strategies for clinical application.

Challenges and future research

The study of ELs has garnered increasing attention, yet current research on their role in cancer faces several significant limitations. The intricate nature of EL metabolism and its interactions with diverse metabolomic pathways demand more sophisticated analytical techniques for accurate characterization. The absence of standardized methodologies complicates the precise identification and quantification of EL species, leading to potential inconsistencies in computational methods [77]. Although ELs play complex roles in various biological processes [78], their specific molecular functions, particularly in disease progression and immune regulation, require further investigation. Furthermore, translating these insights into clinical applications remains challenging because of the lack of targeted drugs and limited in vivo validation. Thus, more comprehensive research is imperative to fully elucidate the role of ELs in cancer.

Applications of multi-omics technologies

In the context of intricate metabolic networks, tools specifically designed to target and dissect the functions and behaviors of ELs are lacking. This deficiency restricts the ability to accurately measure, manipulate, and understand the significance of these lipids, thereby hindering in-depth research into their roles in disease processes [79, 80]. Additionally, the models used to examine complex physiological and pathological processes are often inadequate for exploring the specific contributions of ELs, particularly those related to biological membranes and myelination [78].

Thus, developing more refined tools and representative models is crucial for gaining deeper insights into the functions of ELs and making substantial advances in cancer research.

Multiomics technologies have significantly advanced medical research by identifying disease biomarkers, uncovering metabolic pathways, and enhancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. Lipidomics has illuminated metabolic shifts in liver disease progression and enabled noninvasive CRC diagnosis through an analysis of the tongue coating [81]. Metabolomics has aided in identifying biomarkers linked to cancer-related depression and graft-versus-host disease, providing valuable insights into metabolic reprogramming and potential treatment options [82]. Moreover, the integration of multidimensional omics analyses, such as metagenomic and metabolomic analyses, has revealed stage-specific microbial–metabolite interactions, improving CRC diagnosis through the combination of bacterial and metabolite markers [83]. As omics technologies continue to evolve, including advances in proteomics, single-cell sequencing, and spatial sequencing, their integration with lipidomics will be instrumental in elucidating the relationships between Els, the TME, and the expression of the corresponding proteins. These advancements highlight the potential of multiomics approaches to improve our understanding of diseases, precision medicine, and targeted therapeutic approaches.

Exploration of cancer-related mechanisms

AGPS is a rate-limiting enzyme in EL biosynthesis. Emerging evidence highlighting the involvement of AGPS in LDs provides insights into the intricate crosstalk between lipid metabolism and cancer progression. From a functional perspective, LDs enriched in ELs serve as reservoirs of bioactive lipids and help buffer intracellular stress by sequestering lipid peroxides, thereby mitigating ferroptosis in certain tumor contexts. Conversely, under conditions of lipid mobilization, PUFAs stored in LDs can be oxidized, contributing to ferroptosis. This dual functionality positions LDs at the intersection of survival and death signaling in cancer cells. While AGPS-derived lipids are essentially known to influence membrane curvature, the specific lipid species responsible for initiating or stabilizing LDs have not been fully characterized, and the interplay between AGPS and LD-coating proteins remains unexplored.

Recent studies have revealed a mechanistic link between membrane fluidity, iron uptake, and the sensitivity to ferroptosis in cancer cells. ELs can increase membrane fluidity, which in turn facilitates clathrin-independent endocytosis (CIE) pathways. One such route involves the CD44 receptor, a cell surface glycoprotein that mediates non-transferrin-bound iron uptake in a fluidity-sensitive manner [84]. Increased membrane fluidity promotes the lateral mobility of CD44 within lipid rafts, thereby increasing its clustering and internalization via CIE. This process results in increased intracellular iron accumulation, a hallmark feature that not only supports rapid cancer cell proliferation and metabolic demand but also sensitizes cells to ferroptosis [85]. This connection highlights the potential of targeting EL pathways not only to inhibit tumor growth but also to exploit metabolic liabilities through the induction of ferroptosis. However, the specific EL species that most potently influence membrane fluidity and endocytic pathways remain poorly defined, and direct experimental evidence linking CD44-mediated iron uptake to ferroptosis in the context of altered EL metabolism is still limited.

In the context of lipid-ferroptosis sensitivity, the complex context-dependence of EL synthesis and the regulation of PUFA incorporation into ePLs in lipid-starved cells are not fully understood [33]. ELs help cancer cells resist ferroptosis by reducing lipid peroxidation and maintaining the redox balance [86]. Inhibiting EL biosynthesis, such as by targeting AGPS, can increase lipid peroxidation and sensitize tumors to ferroptosis-inducing therapies [23]. Future research should explore the interplay between EL metabolism and ferroptosis regulators to develop new strategies for overcoming drug resistance in cancer treatment. Additionally, future research should focus on elucidating how EL metabolism interacts with ferroptosis regulators, such as glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), lipid peroxidation pathways, and iron homeostasis.

Development of better cancer therapy

ELs play a crucial role in regulating cancer-associated metabolism, influencing mechanisms of tumor resistance. In pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, these lipids contribute to the maintenance of resistance to complex I inhibitors, and the knockout of key biosynthetic enzymes has been shown to sensitize cancer cells [78]. Similarly, in pheochromocytoma, the disruption of EL metabolism markedly affects tumor cell growth, highlighting its potential as a valuable therapeutic target [80]. Additionally, structural modifications of synthetic alkyl-ELs can alter cellular functions and bioactivity, indicating that optimizing their design could lead to more effective anticancer strategies [87]. The development of highly selective inhibitors of EL metabolism will benefit from the insights obtained from successful inhibitors targeting other metabolic pathways. For instance, inhibitors of fatty acid synthase (FASN) have shown promise in cancer therapy by disrupting FASN, which is essential for the synthesis of lipids required for cancer cell proliferation and membrane formation [88]. EL metabolism is involved in various disease treatment mechanisms, as evidenced by studies on ulcerative colitis, alcoholic liver injury, and the therapeutic effects of ELs on high-fat diet-fed mice [89]. In addition, because ELs facilitate CD44-mediated iron uptake, targeting these processes could suppress tumor cell proliferation while simultaneously inducing ferroptotic cell death, highlighting the dual therapeutic potential of ELs. These results underscore the potential of developing EL-directed interventions as a novel and potent anticancer strategy.

Emerging evidence suggests that ELs also modulate the TME, influencing macrophage polarization and T-cell function [90], which may affect immune evasion and the response to therapy. In melanoma, they are linked to BRAF-mutant tumors and the regulation of the immune microenvironment [91], whereas in head and neck cancer, the involvement of ELs in increasing fatty acid catabolism may contribute to improved treatment responses and immune modulation [92]. Furthermore, their unique biochemical properties make them promising candidates for drug delivery platforms [93]. Research on the interactions between lipids and the immune system highlights their relevance in the action of platinum-based therapies and hypolipidemic drugs, as well as the effects of organophosphorus flame retardants on the nervous and immune systems [94].

Several theories could be tested in future research to improve EL-directed cancer treatment. ELs are highly enriched in metabolically demanding tissues such as the heart and brain, where they contribute to mitochondrial function and membrane organization. Consequently, therapeutic interventions targeting EL metabolism may carry the risk of unintended toxicity, including cardiac impairment, arrhythmias, neurocognitive dysfunction and neurodegeneration. Strategies such as tissue-selective inhibitors or transient pharmacological modulation may help mitigate these risks, ensuring that the therapeutic benefits in cancer are not offset by damage to vital organs. Furthermore, altering EL metabolism may remodel the tumor immune microenvironment to improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy. Creating EL-based nanocarriers and refining synthetic alkyl-ELs may result in new agents and delivery systems with increased safety and potency. When combined, these guidelines provide a logical foundation for converting EL-targeted strategies into clinical settings.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This review has a few noteworthy strengths. First, it provides a thorough and current overview of the research on ether lipids in cancer, including topics such as their production, regulation, and functions in tumor growth and treatment outcomes. Second, it illustrates the promise of ether lipids as biomarkers and therapeutic targets by combining the results from preclinical and new clinical research. Third, this review explicitly links the molecular mechanisms to cancer development and treatment strategies, thereby providing valuable insights for both basic researchers and clinicians. Nevertheless, certain limitations should be acknowledged. While the preclinical evidence is extensive, clinical validation of ether lipid-based biomarkers and therapeutic approaches remains limited, which constrains their direct applicability to patient care. Future work should therefore focus on large-scale clinical investigations and standardized methodologies to bridge the gap between the experimental findings and clinical practice.

Conclusion

Ether lipids are a special type of bioactive lipid that affects signaling networks essential for tumor initiation, progression, and interaction with the TME. Understanding their biosynthesis and functional dynamics provides a platform for identifying novel diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Targeting these lipids through enzyme inhibitors or GAELs has shown promise, particularly in overcoming chemotherapy resistance via apoptosis-independent mechanisms. Combination therapies enhance antitumor efficacy by leveraging synthetic lethality and inducing ferroptosis. Future directions for precision oncology may be made possible by combining lipidomics and multiomics techniques with drug development tactics to alter ether lipid pathways. Continued interdisciplinary research will help to harness the full potential of ether lipid-based interventions in advancing cancer care.

Abbreviations

- ELs

Ether lipids

- PUFAs

Polyunsaturated fatty acids

- GPCRs

G protein-coupled receptors

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- NK

Natural killer

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- DHAP

Dihydroxyacetone phosphate

- AGPS

Alkylglycerone phosphate synthase

- FAR1/2

Fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1/2

- LD

Lipid droplet

- HNRNPK

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K

- CagA

Cytotoxin-associated gene A

- MDM2

Mouse double minute 2

- PUFA-ePLs

Polyunsaturated ether phospholipids

- Hif-2α

Hypoxia-inducible factor alpha

- AGMO

Alkylglycerol monooxygenase

- G3P

Glycerol-3-phosphate

- Selenoi

Selenoprotein I

- CRC

Colorectal cancer

- GAELs

Glycosylated antitumor ether lipids

- MUFA

Monounsaturated fatty acid

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

- EMT

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- EPLs

Ether phospholipids

- DGLA

Dihomo-gamma-linolenic acid

- TAMs

Tumor-associated macrophages

- FAS

Fatty acid synthesis

- CIE

Clathrin-independent endocytosis

- FASN

Fatty acid synthase

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

Authors’ contributions

Paper design: H.Z, H.Z; Writing paper: H.Z, ZH.H, YW.W; Review and edit paper: C.L, W.W, H.Z; Tables and Figure: ZH.H, YW.W.

Funding

Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education Research Project (Natural Sciences, number: Y202353954) (ZH.H), Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (LTGD24H160009) (H.Z), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81600129) (H.Z), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY21H080001 and BY22H205675) (H.Z), National Health Commission Research Fund of Zhejiang province (WKJ-ZJ-2444) (H.Z).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhenghui Hu and Yuwen Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Hui Zeng, Email: zenghuiray@163.com.

Hong Zhou, Email: rainbow0223@sina.com.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pavlova NN, Zhu J, Thompson CB. The hallmarks of cancer metabolism: still emerging. Cell Metab. 2022;34(3):355–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(34):E4966–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang Y-X, Zhao W, Li J, Xie P, Wang S, Yan L, et al. Dietary intake of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids is related to the reduced risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Lipids Health Dis. 2022;21(1):25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dean JM, Lodhi IJ. Structural and functional roles of ether lipids. Protein Cell. 2018;9(2):196–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papin M, Bouchet AM, Chantôme A, Vandier C. Ether-lipids and cellular signaling: A differential role of alkyl- and alkenyl-ether-lipids? Biochimie. 2023;215:50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lessig J, Fuchs B. Plasmalogens in biological systems: their role in oxidative processes in biological membranes, their contribution to pathological processes and aging and plasmalogen analysis. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16(16):2021–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snyder F, Wood R. The occurrence and metabolism of alkyl and alk-1-enyl ethers of glycerol in transplantable rat and mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1968;28(5):972–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorninger F, Forss-Petter S, Berger J. From peroxisomal disorders to common neurodegenerative diseases - the role of ether phospholipids in the nervous system. FEBS Lett. 2017;591(18):2761–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamashita S, Honjo A, Aruga M, Nakagawa K, Miyazawa T. Preparation of marine plasmalogen and selective identification of molecular species by LC-MS/MS. J Oleo Sci. 2014;63(5):423–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braverman NE, Moser AB. Functions of plasmalogen lipids in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(9):1442–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balgoma D, Hedeland M. Etherglycerophospholipids and ferroptosis: structure, regulation, and location. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32(12):960–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Messias MCF, Mecatti GC, Priolli DG, de Oliveira Carvalho P. Plasmalogen lipids: functional mechanism and their involvement in Gastrointestinal cancer. Lipids Health Dis. 2018;17(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali F, Hossain MS, Sejimo S, Akashi K. Plasmalogens inhibit endocytosis of Toll-like receptor 4 to attenuate the inflammatory signal in microglial cells. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(5):3404–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hossain MS, Mawatari S, Fujino T. Plasmalogen-Mediated activation of GPCR21 regulates cytolytic activity of NK cells against the target cells. J Immunol (Baltimore Md: 1950). 2022;209(2):310–25. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Dorninger F, Forss-Petter S, Wimmer I, Berger J. Plasmalogens, platelet-activating factor and beyond - Ether lipids in signaling and neurodegeneration. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;145:105061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin-Perez M, Urdiroz-Urricelqui U, Bigas C, Benitah SA. The role of lipids in cancer progression and metastasis. Cell Metabol. 2022;34(11):1675–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cui W, Liu D, Gu W, Chu B. Peroxisome-driven ether-linked phospholipids biosynthesis is essential for ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(8):2536–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou W, Liu Y, Li H, Song Z, Ma Y, Zhu Y. Mass spectrometry and computer simulation predict the interactions of AGPS and HNRNPK in glioma. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:6181936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng J, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: when metabolism Meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 2025;105(2):651–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salame S, Qasmaoui H, Jose GP, Fleuriot L, Debayle D, Harayama T. Acyltransferases in the first step of glycerophospholipid synthesis have redundant and non-redundant roles in < em > sn- 1 acyl chain regulation, ether lipid levels, and cell survival. BioRxiv. 2024:2024.01.17.576130.

- 23.Zhang Y, Huang Z, Li K, Xie G, Feng Y, Wang Z, et al. TrkA promotes MDM2-mediated AGPS ubiquitination and degradation to trigger prostate cancer progression. J Experimental Clin Cancer Research: CR. 2024;43(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, Liou JM, Peek R, Schulz C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Reviews Disease Primers. 2023;9(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng Y, Lei X, Yang Q, Zhang G, He S, Wang M, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA-mediated ether lipid biosynthesis promotes ferroptosis susceptibility in gastric cancer. Exp Mol Med. 2024;56(2):441–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou Y, Henry WS, Ricq EL, Graham ET, Phadnis VV, Maretich P, et al. Plasticity of ether lipids promotes ferroptosis susceptibility and evasion. Nature. 2020;585(7826):603–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blomme A, Peter C, Mui E, Rodriguez Blanco G, An N, Mason LM, et al. THEM6-mediated reprogramming of lipid metabolism supports treatment resistance in prostate cancer. EMBO Mol Med. 2022;14(3):e14764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xin S, Mueller C, Pfeiffer S, Kraft VAN, Merl-Pham J, Bao X, et al. MS4A15 drives ferroptosis resistance through calcium-restricted lipid remodeling. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(3):670–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agarwala PK, Nie S, Reid GE, Kapoor S. Global lipid remodelling by hypoxia aggravates migratory potential in pancreatic cancer while maintaining plasma membrane homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2023;1868(12):159398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwon J, Bae M, Szamosvári D, Cassilly CD, Bolze AS, Jackson DR, et al. Collinsella aerofaciens produces a pH-Responsive lipid immunogen. J Am Chem Soc. 2023;145(13):7071–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watschinger K, Keller MA, McNeill E, Alam MT, Lai S, Sailer S, et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin and alkylglycerol monooxygenase substantially alter the murine macrophage lipidome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(8):2431–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chornyi S, Ofman R, Koster J, Waterham HR. The origin of long-chain fatty acids required for de Novo ether lipid/plasmalogen synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2023;64(5):100364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sokol KH, Lee CJ, Rogers TJ, Waldhart A, Ellis AE, Madireddy S, et al. Lipid availability influences ferroptosis sensitivity in cancer cells by regulating polyunsaturated fatty acid trafficking. Cell Chem Biol. 2024. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2024.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Benjamin DI, Cozzo A, Ji X, Roberts LS, Louie SM, Mulvihill MM, et al. Ether lipid generating enzyme AGPS alters the balance of structural and signaling lipids to fuel cancer pathogenicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(37):14912–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang X, Yang X, Zhang M, Li T, Zhu K, Dong Y, et al. SELENOI functions as a key modulator of ferroptosis pathway in colitis and colorectal cancer. Adv Sci (Weinheim Baden-Wurttemberg Germany). 2024;11(28):e2404073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartolacci C, Andreani C, Vale G, Berto S, Melegari M, Crouch AC, et al. Targeting de Novo lipogenesis and the lands cycle induces ferroptosis in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4327. 10.1038/s41467-022-31963-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Reed A, Ware T, Li H, Fernando Bazan J, Cravatt BF. TMEM164 is an acyltransferase that forms ferroptotic C20:4 ether phospholipids. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19(3):378–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen L, Dai P, Liu L, Chen Y, Lu Y, Zheng L, et al. The lipid-metabolism enzyme ECI2 reduces neutrophil extracellular traps formation for colorectal cancer suppression. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):7184. 10.1038/s41467-024-51489-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Gajate C, Del Canto-Jañez E, Acuña AU, Amat-Guerri F, Geijo E, Santos-Beneit AM, et al. Intracellular triggering of Fas aggregation and recruitment of apoptotic molecules into Fas-enriched rafts in selective tumor cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2004;200(3):353–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perez MA, Magtanong L, Dixon SJ, Watts JL. Dietary lipids induce ferroptosis in caenorhabditiselegans and human cancer cells. Dev Cell. 2020;54(4):447–e544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papin M, Fontaine D, Goupille C, Figiel S, Domingo I, Pinault M, et al. Endogenous ether lipids differentially promote tumor aggressiveness by regulating the SK3 channel. J Lipid Res. 2024;65(5):100544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guéguinou M, Felix R, Marionneau-Lambot S, Oullier T, Penna A, Kouba S, et al. Synthetic alkyl-ether-lipid promotes TRPV2 channel trafficking trough PI3K/Akt-girdin axis in cancer cells and increases mammary tumour volume. Cell Calcium. 2021;97:102435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berthe W, Sevrain CM, Chantôme A, Bouchet AM, Gueguinou M, Fourbon Y, et al. New Disaccharide-Based ether lipids as SK3 ion channel inhibitors. ChemMedChem. 2016;11(14):1531–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Z, Song Z, Chen Z, Guo Z, Jin H, Ding C, et al. Metabolic and lipidomic characterization of malignant pleural effusion in human lung cancer. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2020;180:113069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang D, Shi R, Xiang W, Kang X, Tang B, Li C, et al. The Agpat4/LPA axis in colorectal cancer cells regulates antitumor responses via p38/p65 signaling in macrophages. Signal Transduct Target Therapy. 2020;5(1):24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li F, Shi Z, Cheng M, Zhou Z, Chu M, Sun L, et al. Biology and roles in diseases of Selenoprotein I characterized by ethanolamine phosphotransferase activity and antioxidant potential. J Nutr. 2023;153(11):3164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stazi G, Battistelli C, Piano V, Mazzone R, Marrocco B, Marchese S, et al. Development of alkyl glycerone phosphate synthase inhibitors: Structure-activity relationship and effects on ether lipids and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer cells. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;163:722–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogunsina M, Samadder P, Idowu T, Nachtigal M, Schweizer F, Arthur G. Syntheses of L-Rhamnose-Linked amino glycerolipids and their cytotoxic activities against human cancer cells. Molecules. 2020;25(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258(5082):607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tewari D, Patni P, Bishayee A, Sah AN, Bishayee A. Natural products targeting the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling pathway in cancer: A novel therapeutic strategy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;80. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Beck JT, Ismail A, Tolomeo C. Targeting the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT/mammalian target of Rapamycin (mTOR) pathway: an emerging treatment strategy for squamous cell lung carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(8):980–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaffrès P-A, Gajate C, Bouchet AM, Couthon-Gourvès H, Chantôme A, Potier-Cartereau M, et al. Alkyl ether lipids, ion channels and lipid raft reorganization in cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;165:114–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Idowu T, Samadder P, Arthur G, Schweizer F. Amphiphilic modulation of glycosylated antitumor ether lipids results in a potent triamino scaffold against epithelial cancer cell lines and BT474 cancer stem cells. J Med Chem. 2017;60(23):9724–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lin Z, Long F, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Yang M, Tang D. The lipid basis of cell death and autophagy. Autophagy. 2024;20(3):469–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xie Y, Li J, Kang R, Tang D. Interplay between lipid metabolism and autophagy. Front Cell Dev Biology. 2020;8:431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seok JK, Hong EH, Yang G, Lee HE, Kim SE, Liu KH et al. Oxidized phospholipids in tumor microenvironment stimulate tumor metastasis via regulation of autophagy. Cells. 2021;10(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Mahmoud G, Jedelská J, Strehlow B, Omar S, Schneider M, Bakowsky U. Photo-responsive tetraether lipids based vesicles for prophyrin mediated vascular targeting and direct phototherapy. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2017;159:720–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Everts PA, Lana JF, Onishi K, Buford D, Peng J, Mahmood A et al. Angiogenesis and Tissue Repair Depend on Platelet Dosing and Bioformulation Strategies Following Orthobiological Platelet-Rich Plasma Procedures: A Narrative Review. Biomedicines. 2023;11(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Baboota RK, Shinde AB, Lemaire K, Fransen M, Vinckier S, Van Veldhoven PP, et al. Functional peroxisomes are required for β-cell integrity in mice. Mol Metab. 2019;22:71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ilhan ZE, Łaniewski P, Thomas N, Roe DJ, Chase DM, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Deciphering the complex interplay between microbiota, HPV, inflammation and cancer through cervicovaginal metabolic profiling. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:675–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sailer S, Keller MA, Werner ER, Watschinger K. The emerging physiological role of AGMO 10 years after its gene identification. Life (Basel). 2021;11(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Rao BD, Chakraborty H, Chaudhuri A, Chattopadhyay A. Differential sensitivity of pHLIP to ester and ether lipids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2020;226:104849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jin Y, Knudsen E, Wang L, Maghazachi AA. Lysophosphatidic acid induces human natural killer cell chemotaxis and intracellular calcium mobilization. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(8):2083–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okamoto S, Olson AC, Vogler WR. Elimination of leukemic cells by the combined use of ether lipids in vitro. Cancer Res. 1987;47(10):2599–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Berdel WE, Fink U, Rastetter J. Clinical phase I pilot study of the alkyl lysophospholipid derivative ET-18-OCH3. Lipids. 1987;22(11):967–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Piano V, Benjamin DI, Valente S, Nenci S, Marrocco B, Mai A, et al. Discovery of inhibitors for the ether Lipid-Generating enzyme AGPS as Anti-Cancer agents. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(11):2589–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nachtigal MW, Musaphir P, Dhiman S, Altman AD, Schweizer F, Arthur G. Cytotoxic capacity of a novel glycosylated antitumor ether lipid in chemotherapy-resistant high grade serous ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo. Translational Oncol. 2021;14(11):101203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gajate C, Mollinedo F. The antitumor ether lipid ET-18-OCH(3) induces apoptosis through translocation and capping of Fas/CD95 into membrane rafts in human leukemic cells. Blood. 2001;98(13):3860–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giantonio BJ, Derry C, McAleer C, McPhillips JJ, O’Dwyer PJ. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic study of the cytotoxic ether lipid Ilmofosine administered by weekly two-hour infusion in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Research: Official J Am Association Cancer Res. 2004;10(4):1282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rangholia N, Leisner TM, Holly SP. Bioactive ether lipids: primordial modulators of cellular signaling. Metabolites. 2021;11(1). 10.3390/metabo11010041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Mollinedo F, Gajate C. Direct Endoplasmic reticulum targeting by the selective alkylphospholipid analog and antitumor ether lipid edelfosine as a therapeutic approach in pancreatic cancer. Cancers. 2021;13:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Liu G-Y, Moon SH, Jenkins CM, Sims HF, Guan S, Gross RW. A functional role for eicosanoid-lysophospholipids in activating monocyte signaling. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(34):12167–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Contursi A, Tacconelli S, Hofling U, Bruno A, Dovizio M, Ballerini P, et al. Biology and Pharmacology of platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase in platelets, cancer cells, and their crosstalk. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022;205:115252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dorninger F, Vaz FM, Waterham HR, Klinken JBv, Zeitler G, Forss-Petter S, et al. Ether lipid transfer across the blood-brain and placental barriers does not improve by inactivation of the most abundant ABC transporters. Brain Res Bull. 2022;189:69–79. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nachtigal MW, Altman AD, Arora R, Schweizer F, Arthur G. The potential of novel lipid agents for the treatment of Chemotherapy-Resistant human epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Araújo R, Fabris V, Lamb CA, Elía A, Lanari C, Helguero LA, et al. Tumor lipid signatures are descriptive of acquisition of therapy resistance in an Endocrine-Related breast cancer mouse model. J Proteome Res. 2024;23(8):2815–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fang X, Miao R, Wei J, Wu H, Tian J. Advances in multi-omics study of biomarkers of glycolipid metabolism disorder. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022;20:5935–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Z, Ho IL, Soeung M, Yen E-Y, Liu J, Yan L, et al. Ether phospholipids are required for mitochondrial reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Corbin LJ, Hughes DA, Bull CJ, Vincent EE, Smith ML, McConnachie A, et al. The metabolomic signature of weight loss and remission in the diabetes remission clinical trial (DiRECT). Diabetologia. 2024;67(1):74–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ghayee HK, Costa KA, Xu Y, Hatch HM, Rodriguez M, Straight SC, et al. Polyamine pathway inhibitor DENSPM suppresses lipid metabolism in pheochromocytoma cell line. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18). 10.3390/ijms251810029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Huang F, Guo W, Chen L, Feng K, Huang T, Cai YD. Identifying Autophagy-Associated proteins and chemicals with a random Walk-Based method within heterogeneous interaction network. Frontiers in bioscience (Landmark edition). 2024;29(1):21. 10.31083/j.fbl2901021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 82.Kumari R, Palaniyandi S, Hildebrandt GC. Metabolic Reprogramming-A new era how to prevent and treat graft versus host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation has begun. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:588449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coker OO, Liu C, Wu WKK, Wong SH, Jia W, Sung JJY, et al. Altered gut metabolites and microbiota interactions are implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis and can be non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers. Microbiome. 2022;10(1):35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Henry WS, Müller S, Yang JS, Innes-Gold S, Das S, Reinhardt F et al. Ether lipids influence cancer cell fate by modulating iron uptake. bioRxiv: the preprint server for biology. 2024.

- 85.Müller S, Sindikubwabo F, Cañeque T, Lafon A, Versini A, Lombard B, et al. CD44 regulates epigenetic plasticity by mediating iron endocytosis. Nat Chem. 2020;12(10):929–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim JW, Lee J-Y, Oh M, Lee E-W. An integrated view of lipid metabolism in ferroptosis revisited via lipidomic analysis. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(8):1620–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Momha R, Le Bot D, Mosset P, Legrand AB. Anti-Angiogenic and cytotoxicity effects of selachyl alcohol analogues. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2022;22(10):1913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stine ZE, Schug ZT, Salvino JM, Dang CV. Targeting cancer metabolism in the era of precision oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2022;21(2):141–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wu F, Lai S, Feng H, Liu J, Fu D, Wang C, et al. Protective effects of protopanaxatriol saponins on ulcerative colitis in mouse based on UPLC-Q/TOF-MS serum and colon metabolomics. Molecules. 2022;27(23). 10.3390/molecules27238346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Morgan PK, Huynh K, Pernes G, Miotto PM, Mellett NA, Giles C, et al. Macrophage polarization state affects lipid composition and the channeling of exogenous fatty acids into endogenous lipid pools. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(6):101341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huang X, Gou W, Song Q, Huang Y, Wen C, Bo X, et al. A BRAF mutation-associated gene risk model for predicting the prognosis of melanoma. Heliyon. 2023;9(5):e15939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ross RB, Gadwa J, Yu J, Darragh LB, Knitz MW, Nguyen D, et al. PPARα agonism enhances immune response to radiotherapy while dietary oleic acid results in counteraction. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30(9):1916–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Deng Y, Li J, Tao R, Zhang K, Yang R, Qu Z, et al. Molecular engineering of electrosprayed hydrogel microspheres to achieve synergistic Anti-Tumor Chemo-Immunotherapy with ACEA cargo. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024;11(17):e2308051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jiang Y, Southam AD, Trova S, Beke F, Alhazmi B, Francis T, et al. Valproic acid disables the Nrf2 anti-oxidant response in acute myeloid leukaemia cells enhancing reactive oxygen species-mediated killing. Br J Cancer. 2022;126(2):275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.