Abstract

Background

Proximal Femur Fractures (PFF) are common among the elderly and can lead to significant disability. Anesthesiological management typically involves Spinal Anesthesia (SA) or Peripheral Nerve Blocks (PNBs). This study aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of SA and PNBs in elderly patients undergoing surgical fixation of PFF. The primary outcome was the comprehensive assessment of intraoperative hemodynamic instability.

Methods

A monocentric, patient-, surgeon-, and assessor-blind randomized study was conducted at the University ‘Federico II’ Hospital of Naples from December 2023 to June 2024. Patients diagnosed with PFF and scheduled for surgery were randomized to receive either Selective Spinal Anesthesia (SSA) (hypobaric bupivacaine 0.5% 7.5 mg and sufentanil 5 µg) or PNBs (femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and sciatic nerve blocks). The study evaluated the efficacy and safety of locoregional procedures by analyzing intraoperative and postoperative adverse events, as well as the effectiveness of analgesia.

Results

The PNB group showed a significantly lower incidence of intraoperative hemodynamic instability (16.7% vs 43.4%, p = 0.048) compared to the SSA group. Bradycardia was also less frequent in the PNB group (10% vs 33.3%, p = 0.028). Although repeated hypotensive episodes occurred in both groups, mean MAP, TWA-MAP and TWA-hypotension remained within safe limits, with brief episode durations and no need for pharmacological intervention. Mobilization was slower in the PNB group; however, these patients experienced a shorter hospital stay. No differences were observed in the need for analgesic rescue doses or in the incidence of postoperative complications, including PONV, DVT, MI, or neurological injury. Pain scores were slightly higher in the SSA group at 6 and 24 h, though the differences were not clinically meaningful. Both groups showed significant increases in NRS and PAINAD scores over time compared to baseline. Motor and sensory block onset was slower and duration longer in the PNB group, while SSA produced a faster onset and earlier resolution. Surgeon satisfaction, as well as estimated and actual surgical durations, were comparable between groups.

Conclusions

PNBs offer an alternative to SSA by providing better intraoperative hemodynamic stability, a lower incidence of postoperative delirium, and improved postoperative analgesia.

Trial registration

This study is registered with Clinicaltrials.gov, number (NCT06155903), registered July, 2, 2023, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT06155903

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s44158-025-00302-6.

Keywords: Randomized controlled study, Spinal anesthesia, Femur fracture, Peripheral nerve block, Locoregional anesthesia, Orthopedic trauma surgery

Background

Proximal Femur Fractures (PFF) represent one of the most common orthopedic injuries worldwide, affecting especially elderly patients with potentially disabling outcomes and a marked impairment of quality of life [1]. The global incidence of PFF in 2000 was approximately 1.6 million and is projected to reach 6 million by 2050 [2]. The vast majority of these occur in women aged over 85, both due to health conditions that may increase the risk of falling and to a simultaneous reduction of bone mass density (i.e., osteoporosis)[3–8].Taking into account their inherent instability, PFF are usually treated surgically within the shortest possible delay in order to reduce the risk of major and minor complications [9–13],the length of hospitalization and related costs [14]. Anesthesiologists play a crucial role in the perioperative management of these patients and in the choice of the type of anesthesia for each patient [15–19].

In this setting, most retrospective and prospective studies have reported a similar 30-day mortality rate comparing Spinal Anesthesia (SA) and General Anesthesia (GA), often recommending an adjuvant Peripheral Nerve Block (PNB) to control postoperative pain [9, 10]. There is consensus that anticoagulant therapy, lack of pharmacological optimization or other conditions may represent a contraindication to SA [10]. These contraindications also apply to Selective Spinal Anesthesia (SSA) despite it decreases intraoperative cardiovascular adverse events (hypotension, bradycardia) and facilitate earlier lower limb mobilization [20]. In these cases, blocking the nerves responsible for innervation of the proximal femur (i.e., the femoral, lateral femoral-cutaneous, obturators and sciatic nerves) may be a useful option [21]. Peripheral Nerve Blocks (PNBs) are carried out after sedation to ensure optimal patient compliance, including a reduction in anxiety that can be evaluated using validated scales [22–24]. There is a lack of high-quality studies assessing the use of PNBs as a viable alternative to SA in patients with PFF.

We hypothesized that PNBs could provide similar intra- and postoperative efficacy and safety as SSA.

This study aimed to compare the incidence of intraoperative and postoperative adverse events, as well as the analgesic efficacy of the PNBs compared to SSA in patients diagnosed with PFF who underwent intramedullary nailing as a method of fixation. The primary outcome was defined as the comprehensive assessment of intraoperative hemodynamic instability.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a single-center, patient-, surgeon-, and assessor-blind randomized trial, conducted between December 2023 and June 2024 at the Department of Surgical Sciences, Orthopaedic Trauma and Emergencies of the University of Naples Federico II (Naples, Italy). The study was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06155903) and approved by Local Ethical Committee (University Federico II—AORN A. Cardarelli) on December 25, 2023. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All procedures performed were in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was conducted according to the CONSORT Guidelines [25].

Participants

The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: age ≥ 65 years, American Society of Anesthesiology Physical Status (ASA-PS) I-IV, diagnosis of PFF and scheduled for fixation through intramedullary nailing within 48 h from hospital admission. The exclusion criteria were: patients with contraindications to SA or PNBs, Local Anesthetic (LA) allergy, central or peripheral neuropathy affecting lower limbs, inability to express written informed consent, refusal to participate in the study or patients for which the treatment protocol could not be fully applied.

The following baseline demographic and clinical data were collected: age; Body Mass Index (BMI, measured in kg/m2); ASA-PS (I-IV); sex; comorbidities and Chronic Kidney Disease Stage (CKDS) evaluated with the Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR ml/min/1.73m2) according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2024 guidelines [26].

Study protocol

Anesthesiologic management

Preoperative

After arrival in the recovery room, a venous access was placed (16—18 Gauge) and antibiotic prophylaxis was administered (Cefazolin 1 or 2 gr. iv, or in case of allergy, Clindamycin 600 mg iv). IV pantoprazole 40 mg was also administered. Pulse Oximetry (SpO2), Heart Rate (HR), Body Temperature (C°), continuous Invasive Blood Pressure (cIBP), cerebral oximetry with ForeSight were monitored. Risk factors of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV) were assessed using the Apfel score [27]. Antiemetic prophylaxis was administered in accordance with the 2020 Fourth Consensus Guidelines for the Management of PONV [28]. A pre-loading with 500 ml of crystalloids iv was administered; pre-procedural sedation was performed with Midazolam 0.03 mg/Kg until a Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) −1 or −2 is obtained [29].

Intraoperative

All patients received intraoperative sedation with Dexmedetomidine at a fixed infusion rate of 0.7 μg/kg/h; based on an estimated average body weight of 70 kg and a surgical duration of approximately 60 min, the expected mean dose per patient was about 49 μg. No supplemental anesthetic agents (e.g., ketamine, propofol, fentanyl) were required during surgery. Oxygen therapy was administered via nasal cannula at a flow rate of 2 L/min. We also proceeded to an intraoperative fluid administration of 15–20 ml/kg/hour of iv crystalloids.

All vital parameters were continuously monitored throughout the intraoperative period, including Heart Rate (HR), Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) and Time Weighted Average MAP (TWA-MAP) automatically calculated by the multiparameter monitor. TWA-MAP represents the MAP integrated over time, accounting for both the magnitude of MAP values and the duration of each measurement interval. In addition, TWA hypotension was calculated following the method described by Wijnberge et al.: TWA hypotension (mmHg) = (65 − MAP) × time spent below a MAP of 65 mmHg/total surgery time, where MAP values below the threshold of 65 mmHg are weighted by their duration and normalized to the total intraoperative monitoring time [30]. This approach provides a standardized measure of both the severity and duration of hypotensive episodes.

The primary endpoint, intraoperative hemodynamic instability, was defined as MAP below 65 mmHg sustained for at least five minutes. We also recorded bradycardia, defined as heart rate below 60 beats per minute for at least five minutes, timing and duration of hypotension, number of hypotensive episodes per patient, and mean MAP and TWA-MAP across the operation [31].

Episodes of MAP < 65 mmHg lasting less than 5 min, without clinical evidence of hypoperfusion, were treated with intravenous crystalloid boluses. According to protocol, persistent or symptomatic hypotension despite fluids prompted the use of vasopressors: ephedrine (0.1 mg/kg) when associated with bradycardia and phenylephrine (100 µg boluses) when accompanied by tachycardia.

Isolated bradycardia was treated with atropine (0.01 mg/kg).

Postoperative

Clinicians assessed the patients to determine: postoperative adverse events (rate of nausea/vomiting and delirium assessed every 6 h in each postoperative period until first 24 h and rate of deep vein thrombosis, myocardial infarction and neurological lesion during the hospital stay); postoperative pain using a Numerical Rate Scale (NRS) and Pain Assessment In Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) scale at end surgery, at 6 h until to 24 h, time to mobilization, rescue dose analgesics needed. Rate of PONV, defined as an incidence of nausea and vomiting 24 h postoperatively, was assessed based on the PONV intensity scale [28, 32]. Postoperative Delirium (POD) was detected by “3-Minute Diagnostic Confusion Assessment Method” (3D-CAM), based on four features: (1) altered mental status/fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) altered level of consciousness, and (4) disorganized thinking [33]. For the prevention and treatment of POD, we followed the 2017 European Society of Anesthesiology guidelines [34]. The diagnosis of Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) was based on postoperative observations of the affected limbs during the patient's hospital stay; the following manifestations were monitored: limb swelling, pain, elevated skin temperature, changes in skin color, venous return disorders, Homans' sign, and Neuhof's sign. Color-Doppler ultrasound was performed bilaterally, in case of positivity of clinical signs and symptoms [35]. The typical symptoms of myocardial ischemia, combined with characteristic changes on an ECG and a significant increase in blood levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponins, have been used to diagnose a Myocardial Infarction (MI). In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, it is necessary to conduct additional non-invasive evaluations, such as an echocardiogram [36]. Neurological lesion was evaluated based on the presence of sensory, motor, or both neurological symptoms [37]. NRS assessment was carried out using a 0–10 scale, with zero meaning “no pain” and 10 meaning “the worst imaginable pain”[38]. PAINAD scale assessed 5 items: facial expression, breathing, negative vocalizations, consolability and body language with a range from 0 to 10 (1–3 = mild pain; 4–6 = moderate pain; 7–10 = severe pain) [39]. Time to mobilization, defined as the time (hours) between LA injection and lower limb mobilization (score 4) on the Bromage scale (1, unable to move feet or knees; 2, able to move feet only; 3, just able to move knees; 4, full flexion of knees and feet) [40]. Pharmacological therapy was based on the patients’ responses. After surgery, we administered intravenous paracetamol 1 g 3 times a day. Ketorolac 30 mg (not for glomerular filtration rate < 50 ml/min) [41], or Oxycodone (up to 0.1 mg/Kg) mg were available as rescue doses. Pain control was considered good in case of NRS and PAINAD score less than or equal to 4. Length of stay, defined as days from hospital admission to discharge, was reported.

Interventions

SSA and PNBs were performed by a team of 4 anesthesiologists, all with considerable experience in Neuraxial Anesthesia (NA) and ultrasound-guided PNBs. The surgical technique was standardized involving reaming of the intramedullary canal and intramedullary nailing.

SSA was performed at the L2–L3 or L3–L4 interspace with the patients lying in the lateral position (fractured side up). Anesthesiologists determined the needling point for spinal anesthesia with reference to Tuffier's line, a virtual line connecting the tops of the iliac crests of a patient. A small dose of LA (4 ml of 1% lidocaine) was injected into the skin and soft tissues at the planned site of spinal needle insertion. The correct path for spinal needle placement was identified with needle infiltration. The technique was performed aseptically in the subarachnoid space after observing clear CerebroSpinal Fluid (CSF) in the spinal needle 25 Gauge, and without releasing the CSF. Selected patients received Hypobaric Bupivacaine 0.5% 7.5 mg and Sufentanil 5 µg and maintained the lateral position for 15 min. At the end of this they were gently placed in supine position.

PNBs were performed on all patients after thorough disinfection of the skin of the lower limb using an ultrasound-guided technique. In general, the needle was inserted using an in-plane approach with a lateral to medial orientation. Hydrodissection was performed by progressively injecting 3 ml of saline solution to ensure the correct position of the needle tip. The anesthesia mixture was injected after performing a negative aspiration test and identifying the target.

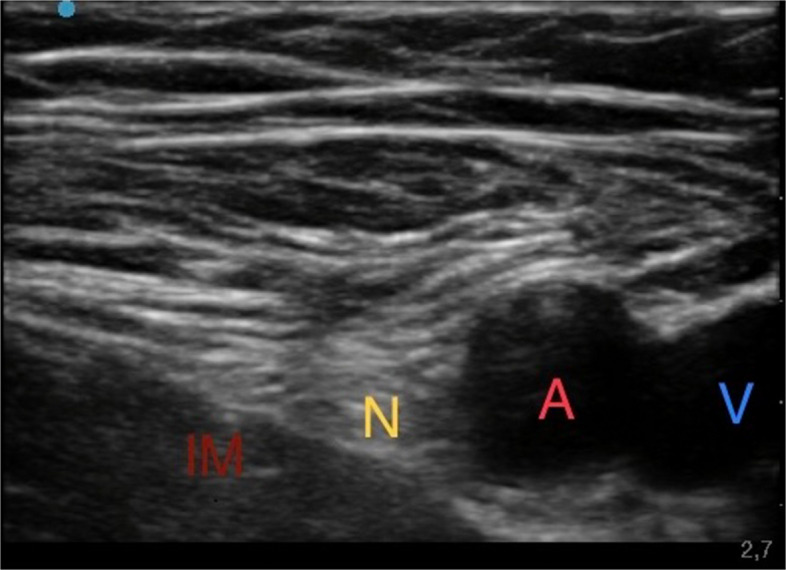

Ultrasound Femoral Nerve Block

First, the patient was positioned in supine decubitus with the lower limbs slightly abducted. With the aid of a linear ultrasound probe (Sonosite HLF38 × 13–6 MHz, Fujifilm Sonosite Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands), the inguinal ligament was located, which presents as a hyperechoic structure; the femoral vein, which is compressible, and the femoral artery, which is noncompressible and pulsatile, were located. More laterally the femoral nerve was identified as a hyperechoic triangle. From the lateral side of the transducer, an 80-mm-long, 21-gauge 30° tip (Pajunk) was inserted to ensure optimal visualization of the needle tip. The needle was directed under continuous ultrasound guidance below the iliac fascia near the lateral aspect of the femoral nerve, and then an anesthetic solution of Ropivacaine 0.375% (dose 26.25 mg) plus Mepivacaine 1% (dose 70 mg) and Dexamethasone 4 mg (total volume 15 ml) were subsequently injected until complete detachment of the iliac fascia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Ultrasound femoral nerve block. Iliac muscle (IM); Femoral nerve (N); Femoral artery (A); Femoral vein (V)

-

b)

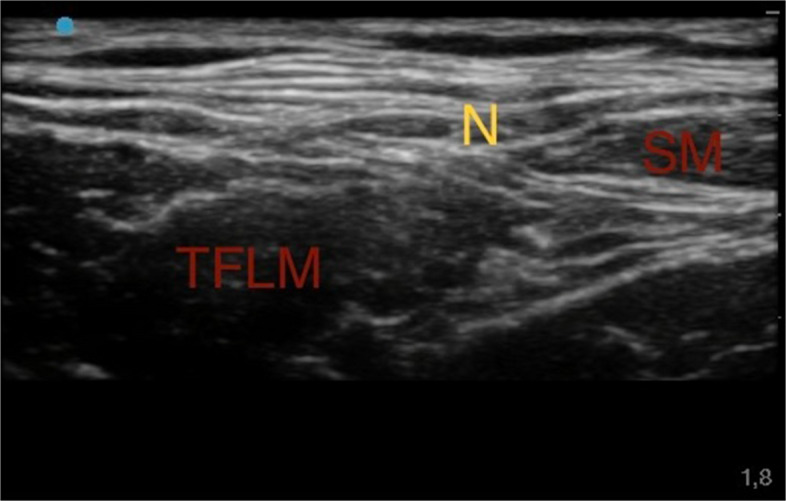

Ultrasound Lateral Femoral-Cutaneous Nerve Block

As second step, after identification of the femoral artery and vein, a lateral probe slide helped visualize the space between the Fascia Lata, Fascia Lata Tensor Muscle and Sartorius Muscle. At this level the lateral femoral-cutaneous nerve with its distinctive "eye" appearance was identified. From the lateral side of the transducer, an 80-mm-long 21-gauge 30° tip (Pajunk) to ensure optimal visualization of the needle tip. An anesthetic solution of Ropivacaine 0.375% (dose 1.875 mg) plus Mepivacaine 1% (dose 5 mg) (total volume 1 ml) was subsequently injected (Fig. 2) [42].

Fig. 2.

Ultrasound lateral femoral-cutaneous nerve block. Sartorius muscle (SM); Tensor fasciae latae muscle (TFLM); Lateral Femoral-Cutaneous nerve (N)

-

c)

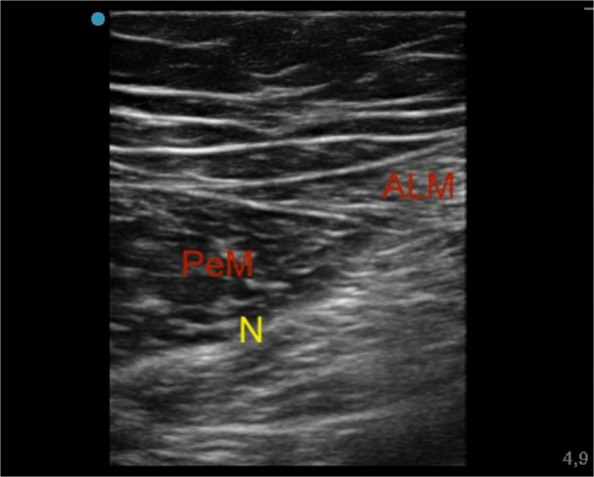

Ultrasound Obturator Nerve Block

Third, being positioned at the patient's groin and surveying the femoral artery and vein, the probe was slid 2–4 cm caudally and then medially until the appearance of the triple layering of the Adductor Longus, Adductor Brevis, and Adductor Magnus muscles. Between these hyperechoic intermuscular septa, the branches of the obturator nerve were identified as flat, oval structures. Once the needle tip was visualized as described above, an anesthetic solution of Ropivacaine 0.375% (dose 9.375 mg) plus Mepivacaine 1% (dose 25 mg) (total volume 5 ml), was injected (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Ultrasound obturator nerve block. Adductor longus muscle (ALM); Pectineus muscle (PeM); Anterior branch of obturator nerve (N)

-

d)

Ultrasound Sciatic Nerve Block, parasacral approach

Last, the patient was positioned in lateral decubitus, with the fractured side positioned upwards. The sacral region was identified. A convex probe was employed, and two anatomical landmarks were identified: the postero-superior iliac spine and the greater trochanter; a connecting line was then drawn between these two. By sliding the probe along this line, with appropriate pressure, rotation, and tilt motion, different anatomical structures were identified, including the piriformis muscle (with a hypoechoic appearance) and the sciatic nerve (with the typical "honeycomb" appearance). From the lateral side of the transducer, a 21 Gauge 30° tip 100 mm long (Pajunk) was inserted to ensure optimal visualization of the needle tip. An anesthetic solution of Ropivacaine 0.375% (dose 37.5 mg) plus Mepivacaine 1% (dose 100 mg) and Dexamethasone 4 mg (total volume 21 ml) was then injected (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Ultrasound sciatic nerve block – Parasacral approach – ecocolordoppler image. Gluteal muscle (GM); Piriformis muscle (PiM); Gluteal artery (A)

Motor, sensory block assessment and surgical data

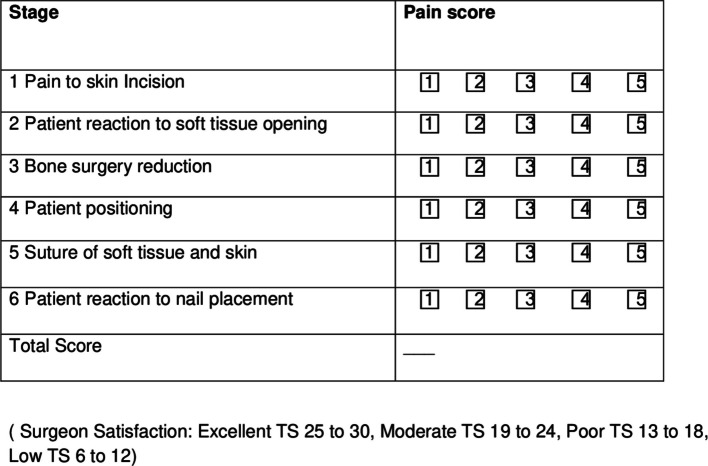

During the execution of the anesthesiologic procedures, the motor and sensory blocks were tested bilaterally using the "Bromage scale" and with the "Hollmen scale", respectively [39, 43]. The presence of complete motor block (Bromage 1) with “unable to move feet or knees”, and complete sensory block (Hollmen 4), tested by pinprick and ice test, defined as “loss of sensation” in the affected limb, defined an adequate anesthesiologic plane [39, 43]. Motor block and sensory block was assessed before LA injection (baseline time) and 10, 15 and 20 min after baseline time and every 30 min during the surgery. Surgical satisfaction level related to the anesthesiologic plane was obtained with a 6-point Likert scale score filled out by the surgeon after surgery (Fig. 6). The result was rated as follows: Excellent’ if total score (TS) was 25 to 30, ‘Moderate’ if TS was 19 to 24, ‘Poor’ if TS was 13 to 18 and ‘Low’ if TS was 6 to 12 (Fig. 5). The duration of surgery, assessed as estimated time and real time, was recorded from skin incision to skin closure.

Fig. 6.

Consort diagram of the study

Fig. 5.

6-point Likert scale for surgical satisfaction

Outcomes assessment

The primary outcome was the hemodynamic instability, defined as MAP less than 65 mmHg, reported as episodes number and percentage;

Secondary outcomes:

bradycardia (HR < 60 beats per minute for more than 5 min), also expressed as absolute numbers and percentages;

the number of hypotensive episodes per patient, categorized as 1 or ≥ 2 episodes;

the requirement for inotropes and/or vasopressors administered during surgery to manage hemodynamic instability;

TWA-MAP (mmHg), defined as the MAP integrated over time and normalized to the total monitoring period, thus accounting for both the magnitude and duration of blood pressure values;

TWA hypotension (mmHg), calculated as the depth of hypotension below a MAP of 65 mm Hg (in millimeters of mercury) × time spent below a MAP of 65 mm Hg (in minutes) divided by total duration of operation (in minutes);

Mean MAP values;

postoperative adverse events (rate of nausea/vomiting and delirium assessed every 6 h in each postoperative period until first 24 h and rate of DVT, MI and neurological lesion during the hospital stay);

postoperative pain evaluated by NRS and PAINAD.

time to mobilization (hours);

need of analgesic rescue dose.

length of stay (days);

Bromage and Hollmen scale of healthy limb and fractured limb assessed at different time.

Other outcome:

surgical satisfaction (evaluated with 6-point Likert scale).

the duration of surgery (min).

Randomization and blinding

After the application of exclusion criteria (18 patients were excluded), patients were allocated to the PNBs group (n = 30) or SSA group (n = 30) in a 1:1 ratio by a web-based system using no random blocks (www.randomizer.org/form.html) (Fig. 6).

The study employed patient-, surgeon-, and assessor-blind design. Patients, surgeons, and outcome assessors were unaware of group assignments. A dedicated anesthesiologist, who did not participate in subsequent patient care or data collection, prepared the anesthetic mixtures and performed the procedures in a separate area. To reduce the likelihood of recognizing the technique, patients received sedation with midazolam (RASS − 1/− 2) and standardized skin dressings before either spinal anesthesia or peripheral nerve blocks.

Although the performing anesthesiologist was necessarily aware of the allocated technique, they were excluded from intraoperative monitoring and postoperative assessment to minimize performance bias. After completion of the block or SA, a second anesthesiologist, blinded to group allocation, assumed intraoperative management, including hemodynamic monitoring and titration of fluids and vasopressors, which constituted the primary outcome. Surgeons and postoperative evaluators remained blind throughout the study.

While sedation and standardized dressings cannot entirely prevent patient awareness of differences in positioning or sensory experience, these measures substantially minimize the risk of unblinding. Under these conditions, the trial design is best characterized as patient-, surgeon-, and assessor-blind rather than fully double-blind.

Statistical analysis

The calculation of the sample size was performed using G*Power program based on the primary outcome [44]. Using an α = 0.05, a power (1-β) = 0.80 and a effect size Cohen’s w = 0.4, two categories (hemodynamic stability or instability) with degrees of Freedom = 1, based on hemodynamic instability rate events expressed as frequencies, with a result of 50. To reduce possible drop-out, 60 patients had to be enrolled. Parametric continuous data were presented as mean and Standard Deviations (SD), while non-parametric continuous data were presented as median and Interquartile Range (IQR). Continuous parametric data were analyzed with two-sided Student’s t test for independent samples and non-parametric ones with Mann–Whitney test for independent samples. Dichotomous categorical data were presented as number of observations and frequencies and analyzed using a χ2 test. A Friedman test for non-parametric data or an ANOVA test for parametric ones was performed to verify differences in pain scores and Bromage scores at different times in the same group; if a statistical difference was found, a Convover post-hoc test or a Dunn test were performed, respectively. The statistical significance was set at 0.05. All the calculations (apart from the sample size calculation) were performed using R studio [45].

Results

The two groups were comparable in terms of age, sex distribution, BMI, ASA-PS, and major comorbidities, including CKDS (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Group SSA (N = 30) | Group PNBs (i = 30) | N = 60 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

| Age (years) | 79.03 (4.9) | 81.2 (6.39) | 0.146 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.9 (3.38) | 27.20 (4.01) | 0.179 |

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value* | |

| ASA- Physical Status | |||

| I | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.137 |

| II | 6 (20%) | 13 (43.3%) | |

| III | 13 (43.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| IV | 11 (36.7%) | 9 (30%) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 9 (30%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.770 |

| Female | 21 (70%) | 23 (76.7%) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| HTN | 27 (90%) | 28 (93.3%) | 0.601 |

| DM | 18 (60%) | 14 (46.7%) | 0.438 |

| CVD | 8 (26.7%) | 11 (36.7%) | 0.579 |

| ICM | 7 (23.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | 1 |

| DSLP | 25 (83.3%) | 20 (66.7%) | 0.233 |

| CVDH | 9 (30%) | 9 (30%) | 1 |

| CAF | 9 (30%) | 9 (30%) | 1 |

| PAF | 10 (33.3%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.778 |

| Previous surgery | 16 (53.3%) | 15 (50%) | 1 |

| Obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 3 (10%) | 8 (26.7%) | 0.182 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease Stage | |||

| I (> 90 ml/min/1.73m2) | 4 (13.3%) | 7 (23.3%) | 0.519 |

| II (60–89 ml/min/1.73m2) | 15 (50%) | 11 (36.7%) | |

| IIIa (45–59 ml/min/1.73m2) | 5 (16.7%) | 4 (13.3%) | |

| IIIb (30–44 ml/min/1.73m2) | 5 (16.7%) | 8 (26.7%) | |

| IV (15–29 ml/min/1.73m2) | 1 (3.33%) | 0 (0%) | |

| V (< 15 ml/min/1.73m2) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

PNBs (peripheral nerve blocks), SD (standard deviation), ASA (American society of anesthesiologists), BMI (body mass index), HTN (hypertension), DM (Diabetes Mellitus), CVD (cerebrovascular disease), ICM (ischemic cardiomyopathy), DSLP (dyslipidemia), CVDH (Chronic Valvular Heart Disease), CAF (chronic atrial fibrillation), PAF (paroxysmal atrial fibrillation), OB (obesity)

*Continuous data were compared with Student’s t test, dichotomous data were compared with χ2test

The PNB group had a significantly lower incidence of intraoperative hemodynamic instability compared to SSA. Bradycardia was also less frequent in the PNB group. Although five patients in the SSA group and one in the PNB group experienced more than one hypotensive episode, mean MAP, TWA-MAP and TWA-hypotension remained within safe limits and were comparable between groups. Episodes were brief in duration (less than 2 min on average) and resolved with crystalloid administration alone, without the need for inotropes and/or vasopressors. These transient episodes of MAP < 65 mmHg did not show clinical signs of tissue hypoperfusion and were not accompanied by relevant tachycardia or bradycardia requiring pharmacological treatment. Hemodynamic stability was promptly restored with intravenous crystalloids, without the need to adjust the dexmedetomidine infusion. The MAP values recorded at the time of the first hypotensive episode were also similar between groups (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Hemodynamic Outcomes

| Group SSA (N = 30) | Group PNBs (N = 30) | N = 60 | |

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value* | |

| Hemodynamic instability | 13 (43.33%) | 5 (16.67%) | 0.048 |

| Bradycardia rate | 10 (33.33%) | 3 (10%) | 0.028 |

| Number of hypotensive episodes per patient** | |||

| 1 episode | 8 (61.5%) | 4 (80%) | 0.394 |

| 2 episodes | 5 (38.5%) | 1 (20%) | |

| Need for inotropes and/or vasopressors | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ° |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

| TWA-MAP (mmHg) TWA-Hypotension (mmHg)** | 66.39 (6.14) | ||

| 0.69 (0.3) | 66.4 (5.45) | ||

| 0.46 (0.27) | 0.991 | ||

| 0.155 | |||

| MAP (mmHg) | 66.57 (6.36) | 66.43 (5.49) | 0.927 |

| MAP at hypotension episode 1 (mmHg) | 58.49 (2.85) | 60.4 (2.51) | 0.202 |

| MAP at hypotension episode 2 (mmHg) | 61.6 (2.07) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Duration of episode 1 (minutes) | 5.23 (0.24) | 5.6 (0.55) | 0.109 |

| Duration of episode 2 (minutes) | 5 (0) | Not applicable | Not applicable |

SSA (selective spinal anesthesia), PNBs (peripheral nerve blocks, TWA-MAP (time weighted average mean arterial pressure), SD (standard deviations)

*Continuous non-parametric data were compared with Mann–Whitney test, dichotomous data were compared with χ2test

° the data were practically costant

**These statistical measures refer only to the patients who experienced hemodynamic instability

The PNB group experienced a slower mobilization but a significantly shorter hospital stay compared to the SSA group. No differences were found in the need for analgesic rescue doses or in the incidence of postoperative complications such as nausea, vomiting, DVT, MI, or neurological injury. Pain scores (NRS and PAINAD) were generally higher in the SSA group, particularly at 6 and 24 h postoperatively. However, the between-group differences were small and not clinically relevant. In both groups, NRS and PAINAD scores increased significantly over time compared to baseline (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes: time to mobilization; need of analgesic rescue dose; postoperative adverse events, numeric rate scale (NRS) and pain assessment in advanced dementia (PANAID) scores; length of stay

| Group SSA (N = 30) | Group PNBs (N = 30) | N = 60 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

| Time to mobilization (hours) | 5.57 (1.06) | 8.2 (0.71) | < 0.001 |

| N (%) | N (%) | p-value* | |

| Need of analgesic rescue dose | 2 (6.67%) | 3 (1%) | ° |

| Postoperative adverse events | |||

| Rate of nausea/vomiting | 8 (26.67%) | 3 (10%) | 0.095 |

| Postoperative delirium | 13 (43.33%) | 4 (13.33%) | 0.021 |

| DVT | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ° |

| MI | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ° |

| Neurological lesion | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | ° |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | p-value* | |

| NRS (points) | |||

| At the end of the surgery | 1 (1–1)¥ | 1 (1–1) ¥ | ° |

| At 6 h after surgery | 2 (2–3) | 1.5 (1–3) | 0.076 |

| At 12 h after surgery | 3 (2–3.75) | 3 (2–3)θ | 0.454 |

| At 24 h after surgery | 2 (2–3) | 2 (2–3) | 0.023 |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| PAINAD (points) | |||

| At the end of the surgery | 1 (1–1) ¥ | 1 (1–1) ¥ | 1 |

| At 6 h after surgery | 3 (2–5) £ | 2 (2–2)$ | < 0.001 |

| At 12 h after surgery | 3 (2–5) | 2 (2–3) | 0.177 |

| At 24 h after surgery | 3 (2–3.75) | 2 (2–3) | 0.848 |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Lenght of stay (days) | 2.25 (2–2.75) | 2 (1.81–2.5) | 0.045 |

SSA (selective spinal anesthesia), PNBs (peripheral nerve blocks), DVT (deep vein thrombosis), MI (myocardial infraction), IQR (interquartile range), SD (standard deviations)

*Continuous non-parametric data were compared with Mann–Whitney test, dichotomous data were compared with χ2test

°The data were practically constant

¥p < 0.05 compared to subsequent controls

Θp < 0.05 compared to 6 and 24 h after surgery

£p < 0.05 compared to 24 h after surgery

$ p < 0.05 compared to subsequent controls

Compared to SSA, the PNB group showed a slower onset and longer duration of both motor and sensory block. The motor block in SSA peaked early and declined more rapidly over time, while in the PNB group, it reached its maximum later and remained stable up to 8 h postoperatively. A similar pattern was observed for sensory block. Intra-group analysis confirmed these trends over time in both groups (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary outcomes: Bromage and Hollmen scales of the fractured limb at different times

| Group SSA (N = 30) | Group PNBs (N = 30) | N = 60 | |

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | p-value* | |

| Modified Bromage scale (grade) | |||

| Baseline time | 4 (4–4)¶ | 4 (4–4)€ | ° |

| After 10 min of LA injections | 1 (1–1)§ | 3 (2–3)Σ | < 0.001 |

| After 15 min of LA injections | 1 (1–1)§ | 2 (2–2) ¥ | < 0.001 |

| After 20 min of LA injections | 1 (1–1)¥ | 1 (1–1)φ | ° |

| After 30 min during the surgery | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | ° |

| **After 60 min during the surgery | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | ° |

| After 2 h of LA injections | 2 (1–2)¥ | 1 (1–1) ¥ | < 0.001 |

| After 6 h of LA injections | 4 (4–4) | 1 (1–2) ¥ | < 0.001 |

| After 8 h of LA injections | 4 (4–4) | 3.5 (3–4)⏁ | < 0.001 |

| After 10 h of LA injections | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | < 0.001 |

| Hollmen scale (grade) | |||

| Baseline time | 1 (1–1)₤ | 1 (1–1)€ | ° |

| After 10 min of LA injections | 4 (4–4) ¥ | 2 (1–2)ψ | < 0.001 |

| After 15 min of LA injections | 4 (4–4)§ | 3 (3–3)γ | < 0.001 |

| After 20 min of LA injections | 4 (4–4) ¥ | 4 (3–4) ¥ | < 0.001 |

| After 30 min during the surgery | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | ° |

| **After 60 min during the surgery | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–4) | ° |

| After 2 h of LA injections | 3 (2–3) ¥ | 3 (2–3) ¥ | 0.522 |

| After 6 h of LA injections | 1 (1–1.75) ¥ | 2 (1.25–2)⏁ | < 0.001 |

| After 8 h of LA injections | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–2) ⏁ | < 0.001 |

| After 10 h of LA injections | 1 (1–1) | 1 (1–1) | ° |

°The data were practically constant

*No Friedman test was performed

**The patients with a surgical time longer than 60 min were 15 in SSA group and 12 in PNBs group

¶p < 0.05 compared to 10 min, 15 min, 20 min, and 2 h

€p < 0.05 compared to subsequent controls, except 10 h

§p < 0.05 compared to 2 h, 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h

Σp < 0.05 compared to the next controls, except 15 min

φp < 0.05 compared to 6 h, 8 h, and 10 h

¥ p < 0.05 compared to the next subsequent controls

⏁p < 0.05 compared to 10 h

₤p < 0.05 compared to 10 min, 15 min, 20 min, 2 h, and 6 h

ψp < 0.05 compared to next controls except 6 h

γp < 0.05 compared to next controls except 2 h

SSA (selective spinal anesthesia), PNBs (peripheral nerve blocks), LA (local anesthetic), IQR (interquartile range), SD (standard deviations)

Surgeon satisfaction related to anesthesiologic plane (evaluated with a 6-point Likert scale), along with estimated and real surgery durations times, was comparable between the two groups. No statistically significant differences were observed across any of the evaluated parameters (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Other outcomes: Likert scale evaluation of head-surgeon’s satisfaction and surgical time

| Group SSA (N = 30) | Group PNBs (N = 30) | N = 60 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | p-value* | |

| Likert scale (points) | |||

| Pain to skin incision | 5 (5–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.076 |

| Patient reaction to soft tissue opening | 5 (4.25–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.321 |

| Bone surgery reduction | 5 (5–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.451 |

| Patient positioning | 5 (5–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.763 |

| Suture of soft tissue and skin | 5 (5–5) | 5 (5–5) | ° |

| Patient reaction to nail placement | 5 (5–5) | 5 (4–5) | 0.076 |

| Satisfaction of the surgeon (total score) | 30 (28–30) | 28 (27–29.75) | 0.065 |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value* | |

| Estimated surgery duration time (minutes) | 57 (9.15) | 57.97 (9.07) | 0.777 |

| Surgery duration time (minutes)θ | 57.77 (10.87) | 57.57 (11.32) | 0.944 |

| 0.767 | 0.880 | ||

θSurgery time is considered from skin incision until to the start of surgical wound closure

°The data were practically constant

SSA (selective spinal anesthesia), PNBs (peripheral nerve blocks), LA (local anesthetic)

The Bromage and Hollmen scores of the healthy limb remained unchanged in both groups throughout the surgical period (Bromage grade 4; Hollmen grade 1) (see Table S1).

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the PNBs group demonstrated a more favorable safety profile, exhibiting lower rates of intraoperative hemodynamic instability and bradycardia, with no difference on clinical impact considering the TWA-MAP, TWA-hypotension, PONV and POD compared to SSA, without postoperative related-hypotension side effects like MI and neurological lesions. Postoperatively, PNBs appeared to offer better pain control, as shown by the higher NRS scores at 24 h and PAINAD scores at 6 h in the SSA group; however, the clinical significance of a one-point difference may be limited. Furthermore, although PNBs required more time to achieve mobilization than SSA, it was associated with a shorter overall length of stay, and there was no significant difference in the need for analgesic rescue doses. Although the need for rescue analgesic doses did not differ significantly between groups, it is worth noting that a slightly higher frequency of administration was observed in the PNB group. This might appear paradoxical in light of the lower pain scores reported in this group at both 6 and 24 h postoperatively. However, this can be reasonably explained by the slower onset of both motor and sensory block in the PNB group, as demonstrated by Bromage and Hollmen scale assessments. Such a delay may have resulted in transient discomfort during the immediate postoperative phase, prompting requests for early rescue medication before the full analgesic effect was established. This apparent paradox can be explained by the timing of onset relative to the surgical procedure. Although PNBs required more time to reach full motor and sensory block, the procedures were initiated only after adequate block depth was confirmed with standardized clinical tests (Bromage and Hollmen scales). Thus, intraoperative analgesia was sufficient, and no supplemental anesthetics were required. However, the slower pharmacodynamic profile of PNBs may have resulted in a transient mismatch between block onset and the early postoperative recovery phase, during which some patients reported discomfort before the block reached its maximal analgesic effect. This could account for the slightly higher frequency of early rescue medication in the PNB group, despite overall lower pain scores at later postoperative assessments.

Importantly, both groups adhered to a standardized postoperative analgesic regimen, without anticipatory or technique-specific modifications. Additionally, interindividual differences in pain perception, early postoperative activity levels, and mobilization timing may have influenced rescue dose administration. Nevertheless, these findings did not translate into a clinically significant difference in pain management efficacy between the two anesthetic strategies. Evaluations of Bromage and Hollmen scales revealed a slower onset and prolonged offset of motor and sensory block in the PNBs group. Lastly, surgeon satisfaction, estimated surgery duration, and actual surgery duration were comparable between SSA and PNBs, underlining their similar procedural feasibility.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first patient-, surgeon-, and assessor-blind randomized study comparing SSA versus PNBs in patients with PFF undergoing surgical fixation using an intramedullary nail.

Several studies have shown improved outcomes of NA compared to GA, although with some limitations [46, 47]. The good clinical practices released by SIAARTI (Società Italiana di Anestesia, Analgesia, Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva) suggest that choosing SA over GA can reduce the occurrence of postoperative complications such as MI, DVT, pulmonary embolism, hypoxia, pneumonia related to ventilation, delirium, and potential increase in hospitalization costs [10, 48]. No patients experienced a postoperative MI. However, studies by P. Hietala et al. and A. Shcherbakov have shown a link between intraoperative bradycardia and/or hypotension and the occurrence of postoperative MI. This discrepancy may be attributed to the limited follow-up period for patients in our study, which was restricted to their hospital stay [49, 50]. We adopted the definition of TWA hypotension as proposed by Wijnberge et al., which accounts for both the depth and duration of hypotension relative to a MAP threshold of 65 mmHg. This allowed us to obtain a time-weighted metric rather than relying solely on single-point measurements or episode counts, thereby providing a more accurate estimate of intraoperative hemodynamic exposure [30]. In a retrospective multicenter cohort study by Luke J. Wachtendorf, patients undergoing noncardiac surgery with a MAP < 55 mm Hg experienced an increased rate of POD; we found similar results in our study [51]. In a randomized trial conducted by M.D. Neuman et colleagues, SA was not superior to GA in patients undergoing hip fracture repair with respect to survival and recovery of ambulation at 60 days and also the incidence of delirium was similar in the two types of anesthesia [52]. Emily A. Vail et al. found no significant difference in 1-year survival rates between SA and GA for hip fracture surgery in another multicenter randomized controlled clinical trial [53]. A previous analysis of data from REGAIN (Regional versus General Anesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture) trial indicated that SA was linked to higher pain levels in the first 24 h after surgery and increased use of prescription analgesics at 60 days compared to GA [54].

The literature supports the possibility of using a loco-regional approach. Elderly patients treated with PNBs have better outcomes compared to those subjected to GA, including lower mortality and shorter hospitalization time [55]. In frail patients, the use of opioid-free anesthetic technique can significantly reduce the impact of adverse events and side effects associated with their use, but not eliminate adverse hemodynamic events, while in selected cases SA has been performed in patients with severe aortic stenosis, maintaining good hemodynamic stability [56, 57]. The literature supports the use of lumbar plexus blocks for anesthesiologic management of hip fracture patients [58]. However, it's worth noting that ESC/ESAIC (European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Anaesthesiologist and Intensive Care) guidelines categorize it as a "deep block" with the same contraindications as neuraxial procedures [59]. Alternatively, an approach characterized by multiple PNBs, such as the one we have proposed, called "Tetrablock," overcomes these limitations by using it in patients in urgency settings, even if not optimized; however, considerable expertise is needed to avoid Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity (LAST) [60, 61]. A recent RCT by Gargano et al. supports this approach by demonstrating effective intraoperative analgesia through a different combination of PNBs, further validating peripheral regional anesthesia as a viable alternative to neuraxial techniques in selected populations [62].

The use of adjuvants in PNBs, such as dexamethasone, help prevent LAST by allowing a reduction of LA dosage in anesthesia mixture; also can result in less interference with sleep or daily activities, and also prolongs postoperative analgesia [63].

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size restricts the generalizability of the findings. Second, full blinding was not feasible: while patients, surgeons, and outcome assessors were blinded, the anesthesiologist performing the intervention was necessarily aware of the allocated technique. Although this anesthesiologist was excluded from intraoperative monitoring and postoperative evaluation to mitigate potential performance bias, subtle bias cannot be completely excluded. Additionally, despite pre-procedural sedation (RASS − 1/− 2) and standardized skin dressings, complete patient unawareness of procedural differences could not be guaranteed. Third, postoperative adverse events (e.g., DVT, MI, neurological injury) were monitored only during the hospital stay, limiting long-term safety assessment. Fourth, motor and sensory block evaluations were performed at fixed intervals using Bromage and Hollmen scores, which do not fully reflect standard clinical practice, where surgical readiness is typically assessed according to the specific anesthetic technique and timing. This approach was adopted to ensure methodological consistency and data coherence. Fifth, the parasacral sciatic nerve block is contraindicated in anticoagulated patients (ESRA/ESAIC 2022 guidelines) and carries a risk of LAST, particularly when performed by less experienced practitioners. Thus, careful patient selection and operator expertise are essential. Another limitation is the off-label use of perineural dexamethasone as an adjuvant in PNBs. While evidence supports its efficacy in prolonging block duration and reducing LA requirements, its off-label application represents a methodological constraint. Finally, surgeon satisfaction was measured using a non-validated 6-point Likert scale designed by the study team, which may introduce bias.

Although SA and SSA remain the standard approaches for PFF, there are clinical scenarios where a multi-block strategy may offer advantages. The combination of femoral, lateral femoral cutaneous, obturator, and sciatic nerve blocks can be performed in patients with absolute or relative contraindications to neuraxial anesthesia (e.g., severe aortic stenosis, anticoagulation, or spinal deformities). While a parasacral sciatic block shares some contraindications with SA, the overall tetrablock approach allows tailoring of the anesthetic plan, and in selected cases a sciatic block can be omitted or replaced with alternative approaches (e.g., subgluteal). Moreover, avoiding intrathecal injection may reduce the risk of severe hypotension and bradycardia in frail patients. Despite being more time-consuming and requiring advanced expertise, this approach may therefore be valuable in high-risk or contraindicated populations.

Conclusions

SSA and PNBs are commonly used in clinical practice for patients with PFF who candidates for surgical fixation are using intramedullary nailing. Both methods can influence the occurrence of adverse effects, particularly in high-risk groups.

PNBs have been associated with a lower incidence of intraoperative adverse events and a reduced risk of postoperative delirium, as well as providing better postoperative pain relief. Furthermore, the rate of other adverse events observed with PNBs is comparable to that of SA.

Our data suggest that PNBs could be a preferred technique; however, the limited evidence due to the small number of enrolled patients prevents us from drawing a definitive conclusion. Though regional anesthesia is not a cure-all, its appropriate use in selected patients can lead to improved surgical outcomes. Future studies should further refine blinding strategies, as the inability to achieve full double-blind conditions in regional anesthesia trials remains an important methodological challenge and a potential source of bias. Additional multicenter studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate these findings.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Secondary outcomes: Bromage and Hollmen scales of the healthy limb at different times.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to Dr. Mario Tedesco and Dr. Giuseppe Sepolvere for having applied the Tetrablock technique in various types of patients, which later inspired its application in the context of proximal femur fractures. Their pioneering work in the use of multiple peripheral nerve blocks has significantly contributed to the development of this approach in clinical practice.

Abbreviations

- PFF

Proximal femur fracture

- SA

Spinal anesthesia

- GA

General anesthesia

- PNB

Peripheral nerve block

- SSA

Selective spinal anesthesia

- PNBs

Peripheral nerve blocks

- ASA–PS

American Society of Anesthesiology–Physical Status

- LA

Local anesthetic

- BMI

Body Mass Index

- CKDS

Chronic Kidney Disease Stage

- eGFR

Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate

- KDIGO

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes

- HR

Heart rate

- cIBP

Continuous invasive blood pressure

- PONV

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

- RASS

Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale

- MAP

Mean arterial pressure

- TWA-MAP

Time Weighted Average MAP

- NA

Neuraxial anesthesia

- CSF

Cerebro-spinal fluid

- NRS

Numerical Rate Scale

- PAINAD

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia

- POD

Postoperative delirium

- 3D-CAM

3-Minute Diagnostic Confusion Assessment Method

- PACU

Post-anesthesia care unit

- SD

Standard deviations

- IQR

Interquartile range

- HTN

Hypertension

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- CVD

Cerebrovascular Disease

- ICM

Ischemic cardiomyopathy

- DSLP

Dyslipidemia

- CVDH

Chronic valvular heart disease

- CAF

Chronic atrial fibrillation

- PAF

Paroxysmal atrial fibrillation

- SIAARTI

Società Italiana di Anestesia, Analgesia, Rianimazione e Terapia Intensiva

- REGAIN

Regional versus General Anesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture

- ESC/ESAIC

European Society of Cardiology/European Society of Anaesthesiologist and Intensive Care)

- LAST

Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity

- DVT

Deep vein thrombosis

- MI

Myocardial infarction

Authors’ contributions

A. C.: contributed for study design, conduct of the study and manuscript preparation; D.C. and A.B.: contributed to patient enrollment, data curation and manuscript preparation; A.U.d.S.: performed the statistical analysis; E.S contributed to investigation and visualization; M.S.B. and I.P.: contributed to patient enrollment and data collection; G.R. and A.T.: contributed for study design and helped with data collection; G. S.: supervised and critically reviewed the final version of the article before submission; C. I.: contributed for study design, and manuscript preparation. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Data availability

All data and related metadata underlying the findings reported in our study are provided as part of the submitted article. Additional data is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Local Ethical Committee (University Federico II—AORN A. Cardarelli), on December 25, 2023; all study participants signed the informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Every human participant should provide their consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Study design

This study aimed to compare the incidence of intraoperative and postoperative adverse events, as well as the analgesic efficacy of the peripheral nerve blocks compared to selective spinal anesthesia in patients diagnosed with proximal femur fracture who underwent intramedullary nailing as a method of fixation.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Cummings SR, Melton LJ (2002) Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 359(9319):1761–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El Madboh MS, Yonis LMAE, Kabbash IA, Samy AM, Romeih MAE (2021) Proximal femoral plate, intramedullary nail fixation versus hip arthroplasty for unstable intertrochanteric femoral fracture in the elderly: a meta-analysis. Indian J Orthop 56(1):155–161. 10.1007/s43465-021-00426-1. (PMID: 35070156; PMCID: PMC8748604) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanis JA, Odén A, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Wahl DA, Cooper C, IOF Working Group on Epidemiology and Quality of Life (2012) A systematic review of hip fracture incidence and probability of fracture worldwide. Osteoporos Int 23(9):2239–2256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pisani P, Renna MD, Conversano F, Casciaro E, Di Paola M, Quarta E, Muratore M, Casciaro S (2016) Major osteoporotic fragility fractures: risk factor updates and societal impact. World J Orthop 7(3):171–181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grisso JA, Kelsey JL, Strom BL, Chiu GY, Maislin G, O’Brien LA, Hoffman S, Kaplan F (1991) Risk factors for falls as a cause of hip fracture in women. The Northeast Hip Fracture Study Group. N Engl J Med 324(19):1326–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rapp K, Becker C, Cameron ID, Klenk J, Kleiner A, Bleibler F, König HH, Büchele G (2012) Femoral fracture rates in people with and without disability. Age Ageing 41(5):653–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benzinger P, Rapp K, Maetzler W, König H-H, Jaensch A, Klenk J, Büchele G (2014) Risk for femoral fractures in Parkinson’s disease patients with and without severe functional impairment. PLoS ONE 9(5):e97073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loriaut P, Loriaut P, Boyer P, Massin P, Cochereau I (2014) Visual impairment and hip fractures: a case-control study in elderly patients. Ophthalmic Res 52(4):212–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Società Italiana di Ortopedia e Traumatologia. Fratture del femore prossimale nell’anziano.Linea guida SIOT 2021. https://siot.it/lineeguida-fratturafemore2021

- 10.La gestione anestesiologica della frattura di femore nel paziente anziano. Buone Pratiche Cliniche SIAARTI 2018. https://www.siaarti.it/news/370736

- 11.Moran CG, Wenn RT, Sikand M, Taylor AM (2005) Early mortality after hip fracture: is delay before surgery important? J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(3):483–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiga T, Wajima Z, Ohe Y (2008) Is operative delay associated with increased mortality of hip fracture patients? Systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Can J Anaesth 55(3):146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan SK, Kalra S, Khanna A, Thiruvengada MM, Parker MJ (2009) Timing of surgery for hip fractures: a systematic review of 52 published studies involving 291,413 patients. Injury 40(7):692–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piscitelli P, Neglia C, Feola M, Rizzo E, Argentiero A, Ascolese M, Rivezzi M, Rao C, Miani A, Distante A, Esposito S, Iolascon G, Tarantino U. Updated incidence and costs of hip fractures in elderly Italian population. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2020 Feb 13. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.National Clinical Guideline Centre. The Management of Hip Fracture in Adults. NICE clinical guideline 124. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Jun 2011

- 16.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Evidence Update 34 – Hip fracture (March 2013)

- 17.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Appendix A: decision matrix 4-year surveillance 2015 – Hip fracture (2011) NICE guideline CG124 [PubMed]

- 18.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Addendum to Clinical Guideline 124, Hip fracture: management. 2017 [PubMed]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2019 surveillance of hip fracture: management (CG124) – Appendix A [PubMed]

- 20.Moosavi Tekye SM, Alipour M (2014) Comparison of the effects and complications of unilateral spinal anesthesia versus standard spinal anesthesia in lower-limb orthopedic surgery. Brazilian Journal of Anesthesiology (English Edition) 64(3):173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang A, Breeland G, Black AC, et al. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Femur. [Updated 2023 Nov 17]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532982/ [PubMed]

- 22.Buonanno P, Laiola A, Palumbo C, Spinelli G, Terminiello V, Servillo G (2017) Italian validation of the Amsterdam preoperative anxiety and information scale. Minerva Anestesiol 83(7):705–711. 10.23736/S0375-9393.16.11675-X. (Epub 2017 Jan 17. PMID: 28094483) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moerman N, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Oosting H (1996) The Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS). Anesth Analg 82(3):445–451. 10.1097/00000539-199603000-00002. (PMID: 8623940) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nowicka-Sauer K, Zemła A, Banaszkiewicz D, Trzeciak B, Jarmoszewicz K (2024) Measures of preoperative anxiety: Part two. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther 56(1):9–16. 10.5114/ait.2024.136508. (PMID: 38741439; PMCID: PMC11022642) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuschieri S (2019) The CONSORT statement. Saudi J Anaesth 13(Suppl 1):S27–S30. 10.4103/sja.SJA_559_18. (PMID: 30930716; PMCID: PMC6398298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group (2024) KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 105(4S):S117–S314. 10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018. (PMID: 38490803) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tran VN, Fitzpatrick BJ, Das S (2023) Antiemetics and Apfel scores in orthopedic surgery. Hosp Pharm 58(5):511–518. 10.1177/00185787231169458. (PMID: 37711405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gan TJ, Belani KG, Bergese S, Chung F, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Jin Z, Kovac AL, Meyer TA, Urman RD, Apfel CC, Ayad S, Beagley L, Candiotti K, Englesakis M, Hedrick TL, Kranke P, Lee S, Lipman D, Minkowitz HS, Morton J, Philip BK (2020) Fourth consensus guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg 131(2):411–448. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004833. (Erratum in: Anesth Analg. 2020 Nov;131(5):e241. PMID: 32467512) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pop MK, Dervay KR, Dansby M, Jones C (2018) Evaluation of Richmond agitation sedation scale (RASS) in mechanically ventilated in the emergency department. Adv Emerg Nurs J 40(2):131–137. 10.1097/TME.0000000000000184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wijnberge M, Geerts BF, Hol L, Lemmers N, Mulder MP, Berge P, Schenk J, Terwindt LE, Hollmann MW, Vlaar AP, Veelo DP (2020) Effect of a machine learning-derived early warning system for intraoperative hypotension vs standard care on depth and duration of intraoperative hypotension during elective noncardiac surgery: the HYPE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 323(11):1052–1060. 10.1001/jama.2020.0592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung CC, Martyn A, Campbell N, Frost S, Gilbert K, Michota F, Seal D, Ghali W, Khan NA (2015) Predictors of intraoperative hypotension and bradycardia. Am J Med 128(5):532–538. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.11.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wengritzky R, Mettho T, Myles PS, Burke J, Kakos A (2010) Development and validation of a postoperative nausea and vomiting intensity scale. Br J Anaesth 104(2):158–166. 10.1093/bja/aep370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oberhaus J, Wang W, Mickle AM, Becker J, Tedeschi C, Maybrier HR, Upadhyayula RT, Muench MR, Lin N, Schmitt EM, Inouye SK, Avidan MS (2021) Evaluation of the 3-minute diagnostic confusion assessment method for identification of postoperative delirium in older patients. JAMA Netw Open 4(12):e2137267. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.37267. (PMID: 34902038; PMCID: PMC8669542) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aldecoa C, Bettelli G, Bilotta F, Sanders RD, Audisio R, Borozdina A, Cherubini A, Jones C, Kehlet H, MacLullich A, Radtke F, Riese F, Slooter AJ, Veyckemans F, Kramer S, Neuner B, Weiss B, Spies CD (2017) European society of anaesthesiology evidence-based and consensus-based guideline on postoperative delirium. Eur J Anaesthesiol 34(4):192–214. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000594. (Erratum in: Eur J di Anaesthesiol. 2018 Sep;35(9):718-719. PMID: 28187050) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu X, Wu Y, Ning R (2021) The deep vein thrombosis of lower limb after total hip arthroplasty: what should we care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1):547. 10.1186/s12891-021-04417-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao L, Chen L, He J, Wang B, Liu C, Wang R, Fan L, Cheng R (2022) Perioperative myocardial injury/infarction after non-cardiac surgery in elderly patients. Front Cardiovasc Med 9:910879. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.910879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alasdair Taylor, Calum RK Grant, Complications of regional anaesthesia, Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine. 23(3), 2022. 146–150, ISSN 1472–0299, 10.1016/j.mpaic.2021.11.007

- 38.Jensen MP, Karoly P, Braver S (1986) The measurement of clinical pain intensity: a comparison of six methods. Pain 27:117–126. 10.1016/0304-3959(86)90228-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer L (2003) Development and psychometric evaluation of the pain assessment in advanced dementia (PAINAD) scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc 4(1):9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Craig D, Carli F (2018) Bromage motor blockade score - a score that has lasted more than a lifetime. Can J Anaesth 65(7):837–838. 10.1007/s12630-018-1101-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahmoodi AN, Kim PY. Ketorolac. [Updated 2022 Apr 9]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- 42.Bodner G, Bernathova M, Galiano K, Putz D, Martinoli C, Felfernig M (2009) Ultrasound of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: normal findings in a cadaver and in volunteers. Reg Anesth Pain Med 34(3):265–268. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31819a4fc6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee R, Kim YM, Choi E, Choi Y, Chung Mi (2012) Effect of warmed ropivacaine solution on onset and duration of axillary block. Korean J Anesthesiol 62:52–56. 10.4097/kjae.2012.62.1.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang H (2021) Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof 18:17. 10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan BKC (2018) Data analysis using R programming. Adv Exp Med Biol 1082:47–122. 10.1007/978-3-319-93791-5_2. (PMID: 30357717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen DX, Yang L, Ding L, Li SY, Qi YN, Li Q (2019) Perioperative outcomes in geriatric patients undergoing hip fracture surgery with different anesthesia techniques: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98(49):e18220. 10.1097/MD.0000000000018220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luger TJ, Kammerlander C, Gosch M, Luger MF, Kammerlander-Knauer U, Roth T et al (2010) Neuroaxial versus general anaesthesia in geriatric patients for hip fracture surgery: does it matter? Osteoporos Int 21(Suppl 4):S555–S572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Robertis E, Zito Marinosci G, Romano GM, Piazza O, Iannuzzi M, Cirillo F, De Simone S, Servillo G (2016) The use of sugammadex for bariatric surgery: Analysis of recovery time from neuromuscular blockade and possible economic impact. Clin Outcomes Res 8:317–322. 10.2147/CEOR.S109951. (PMID: 27418846; PMCID: PMC4934482) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hietala P, Strandberg M, Strandberg N, Gullichsen E, Airaksinen KE (2013) Perioperative myocardial infarctions are common and often unrecognized in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 74(4):1087–1091. 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182827322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shcherbakov A, Bisharat N (2022) Associations between different measures of intra-operative tachycardia during noncardiac surgery and adverse postoperative outcomes. Eur J Anaesthesiol 39(2):145–151. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001618. (PMID: 34690273) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wachtendorf LJ, Azimaraghi O, Santer P, Linhardt FC, Blank M, Suleiman A, Ahn C, Low YH, Teja B, Kendale SM, Schaefer MS, Houle TT, Pollard RJ, Subramaniam B, Eikermann M, Wongtangman K (2022) Association between intraoperative arterial hypotension and postoperative delirium after noncardiac surgery: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Anesth Analg 134(1):822–833. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neuman MD, Feng R, Carson JL, Gaskins LJ, Dillane D, Sessler DI, Sieber F, Magaziner J, Marcantonio ER, Mehta S, Menio D, Ayad S, Stone T, Papp S, Schwenk ES, Elkassabany N, Marshall M, Jaffe JD, Luke C, Sharma B, Azim S, Hymes RA, Chin KJ, Sheppard R, Perlman B, Sappenfield J, Hauck E, Hoeft MA, Giska M, Ranganath Y, Tedore T, Choi S, Li J, Kwofie MK, Nader A, Sanders RD, Allen BFS, Vlassakov K, Kates S, Fleisher LA, Dattilo J, Tierney A, Stephens-Shields AJ, Ellenberg SS, REGAIN Investigators (2021) Spinal anesthesia or general anesthesia for hip surgery in older adults. N Engl J Med 385(25):2025–2035. 10.1056/NEJMoa2113514. (PMID: 34623788) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vail EA, Feng R, Sieber F, Carson JL, Ellenberg SS, Magaziner J, Dillane D, Marcantonio ER, Sessler DI, Ayad S, Stone T, Papp S, Donegan D, Mehta S, Schwenk ES, Marshall M, Jaffe JD, Luke C, Sharma B, Azim S, Hymes R, Chin KJ, Sheppard R, Perlman B, Sappenfield J, Hauck E, Tierney A, Horan AD, Neuman MD, REGAIN (Regional versus General Anesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture) Investigators (2024) Long-term outcomes with spinal versus general anesthesia for hip fracture surgery: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology 1(3):375–386. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000004807. (PMID: 37831596; PMCID: PMC11186520) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neuman MD, Feng R, Ellenberg SS, Sieber F, Sessler DI, Magaziner J, Elkassabany N, Schwenk ES, Dillane D, Marcantonio ER, Menio D, Ayad S, Hassan M, Stone T, Papp S, Donegan D, Marshall M, Jaffe JD, Luke C, Sharma B, Azim S, Hymes R, Chin KJ, Sheppard R, Perlman B, Sappenfield J, Hauck E, Hoeft MA, Tierney A, Gaskins LJ, Horan AD, Brown T, Dattilo J, Carson JL; REGAIN (Regional versus General Anesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture) Investigators*; Looke T, Bent S, Franco-Mora A, Hedrick P, Newbern M, Tadros R, Pealer K, Vlassakov K, Buckley C, Gavin L, Gorbatov S, Gosnell J, Steen T, Vafai A, Zeballos J, Hruslinski J, Cardenas L, Berry A, Getchell J, Quercetti N, Bajracharya G, Billow D, Bloomfield M, Cuko E, Elyaderani MK, Hampton R, Honar H, Khoshknabi D, Kim D, Krahe D, Lew MM, Maheshwer CB, Niazi A, Saha P, Salih A, de Swart RJ, Volio A, Bolkus K, DeAngelis M, Dodson G, Gerritsen J, McEniry B, Mitrev L, Kwofie MK, Belliveau A, Bonazza F, Lloyd V, Panek I, Dabiri J, Chavez C, Craig J, Davidson T, Dietrichs C, Fleetwood C, Foley M, Getto C, Hailes S, Hermes S, Hooper A, Koener G, Kohls K, Law L, Lipp A, Losey A, Nelson W, Nieto M, Rogers P, Rutman S, Scales G, Sebastian B, Stanciu T, Lobel G, Giampiccolo M, Herman D, Kaufman M, Murphy B, Pau C, Puzio T, Veselsky M, Apostle K, Boyer D, Fan BC, Lee S, Lemke M, Merchant R, Moola F, Payne K, Perey B, Viskontas D, Poler M, D'Antonio P, O'Neill G, Abdullah A, Fish-Fuhrmann J, Giska M, Fidkowski C, Guthrie ST, Hakeos W, Hayes L, Hoegler J, Nowak K, Beck J, Cuff J, Gaski G, Haaser S, Holzman M, Malekzadeh AS, Ramsey L, Schulman J, Schwartzbach C, Azefor T, Davani A, Jaberi M, Masear C, Haider SB, Chungu C, Ebrahimi A, Fikry K, Marcantonio A, Shelvan A, Sanders D, Clarke C, Lawendy A, Schwartz G, Garg M, Kim J, Caruci J, Commeh E, Cuevas R, Cuff G, Franco L, Furgiuele D, Giuca M, Allman M, Barzideh O, Cossaro J, D'Arduini A, Farhi A, Gould J, Kafel J, Patel A, Peller A, Reshef H, Safur M, Toscano F, Tedore T, Akerman M, Brumberger E, Clark S, Friedlander R, Jegarl A, Lane J, Lyden JP, Mehta N, Murrell MT, Painter N, Ricci W, Sbrollini K, Sharma R, Steel PAD, Steinkamp M, Weinberg R, Wellman DS, Nader A, Fitzgerald P, Ritz M, Bryson G, Craig A, Farhat C, Gammon B, Gofton W, Harris N, Lalonde K, Liew A, Meulenkamp B, Sonnenburg K, Wai E, Wilkin G, Troxell K, Alderfer ME, Brannen J, Cupitt C, Gerhart S, McLin R, Sheidy J, Yurick K, Chen F, Dragert K, Kiss G, Malveaux H, McCloskey D, Mellender S, Mungekar SS, Noveck H, Sagebien C, Biby L, McKelvy G, Richards A, Abola R, Ayala B, Halper D, Mavarez A, Rizwan S, Choi S, Awad I, Flynn B, Henry P, Jenkinson R, Kaustov L, Lappin E, McHardy P, Singh A, Donnelly J, Gonzalez M, Haydel C, Livelsberger J, Pazionis T, Slattery B, Vazquez-Trejo M, Baratta J, Cirullo M, Deiling B, Deschamps L, Glick M, Katz D, Krieg J, Lessin J, Mojica J, Torjman M, Jin R, Salpeter MJ, Powell M, Simmons J, Lawson P, Kukreja P, Graves S, Sturdivant A, Bryant A, Crump SJ, Verrier M, Green J, Menon M, Applegate R, Arias A, Pineiro N, Uppington J, Wolinsky P, Gunnett A, Hagen J, Harris S, Hollen K, Holloway B, Horodyski MB, Pogue T, Ramani R, Smith C, Woods A, Warrick M, Flynn K, Mongan P, Ranganath Y, Fernholz S, Ingersoll-Weng E, Marian A, Seering M, Sibenaller Z, Stout L, Wagner A, Walter A, Wong C, Orwig D, Goud M, Helker C, Mezenghie L, Montgomery B, Preston P, Schwartz JS, Weber R, Fleisher LA, Mehta S, Stephens-Shields AJ, Dinh C, Chelly JE, Goel S, Goncz W, Kawabe T, Khetarpal S, Monroe A, Shick V, Breidenstein M, Dominick T, Friend A, Mathews D, Lennertz R, Sanders R, Akere H, Balweg T, Bo A, Doro C, Goodspeed D, Lang G, Parker M, Rettammel A, Roth M, White M, Whiting P, Allen BFS, Baker T, Craven D, McEvoy M, Turnbo T, Kates S, Morgan M, Willoughby T, Weigel W, Auyong D, Fox E, Welsh T, Cusson B, Dobson S, Edwards C, Harris L, Henshaw D, Johnson K, McKinney G, Miller S, Reynolds J, Segal BS, Turner J, VanEenenaam D, Weller R, Lei J, Treggiari M, Akhtar S, Blessing M, Johnson C, Kampp M, Kunze K, O'Connor M, Looke T, Tadros R, Vlassakov K, Cardenas L, Bolkus K, Mitrev L, Kwofie MK, Dabiri J, Lobel G, Poler M, Giska M, Sanders D, Schwartz G, Giuca M, Tedore T, Nader A, Bryson G, Troxell K, Kiss G, Choi S, Powell M, Applegate R, Warrick M, Ranganath Y, Chelly JE, Lennertz R, Sanders R, Allen BFS, Kates S, Weigel W, Li J, Wijeysundera DN, Kheterpal S, Moore RH, Smith AK, Tosi LL, Looke T, Mehta S, Fleisher L, Hruslinski J, Ramsey L, Langlois C, Mezenghie L, Montgomery B, Oduwole S, Rose T; REGAIN (Regional versus General Anesthesia for Promoting Independence after Hip Fracture) Investigators. Pain, Analgesic Use, and Patient Satisfaction With Spinal Versus General Anesthesia for Hip Fracture Surgery : A Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022 Jul;175(7):952–960. 10.7326/M22-0320. Epub 2022 Jun 14. PMID: 35696684 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Desai V, Chan PH, Prentice HA et al (2018) Is anesthesia technique associated with a higher risk of mortality or complications within 90 days of surgery for geriatric patients with hip fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res 476(6):1178–1188. 10.1007/s11999.0000000000000147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coviello A, Golino L, Maresca A, Vargas M, Servillo G (2021) Erector spinae plane block in laparoscopic nephrectomy as a cause of involuntary hemodynamic instability: a case report. Clin Case Rep 9(5):e04026. 10.1002/ccr3.4026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coviello A, Ianniello M, Spasari E, Posillipo C, Vargas M, Maresca A, Servillo G (2021) Low-dose spinal and opioid-free anesthesia in patient with severe Aortic Stenosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection: case report. Clin Case Rep 9(8):e04192. 10.1002/ccr3.4192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ahamed ZA, Sreejit MS (2019) Lumbar plexus block as an effective alternative to subarachnoid block for intertrochanteric hip fracture surgeries in the elderly. Anesth Essays Res 13(2):264–268. 10.4103/aer.AER_39_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kietaibl S, Ferrandis R, Godier A, Llau J, Lobo C, Macfarlane AJ, Schlimp CJ, Vandermeulen E, Volk T, von Heymann C, Wolmarans M, Afshari A (2022) Regional anaesthesia in patients on antithrombotic drugs: joint ESAIC/ESRA guidelines. Eur J Anaesthesiol 39(2):100–132. 10.1097/EJA.0000000000001600. (PMID: 34980845) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Coviello A, Iacovazzo C, Cirillo D, Diglio P, Bernasconi A, Cozzolino A, Izzo A, Marra A, Servillo G, Vargas M (2023) Tetra-block: ultrasound femoral, lateral femoral-cutaneous, obturator, and sciatic nerve blocks in lower limb anesthesia: a case series. J Med Case Rep 17(1):270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drasner K (2010) Local anesthetic systemic toxicity: a historical perspective. Reg Anesth Pain Med 35(2):162–166. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e3181d2306c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gargano F, Migliorelli S, Pascarella G, Costa F, Strumia A, Bellezze A, Ruggiero A, Carassiti M (2025) A randomized clinical trial comparing different combination of peripheral nerve blocks for intraoperative analgesia in patients on antithrombotic drugs undergoing hip fracture surgery: pericapsular nerve group (PENG) block versus femoral and obturator nerve block. Minerva Anestesiol 91(6):524–532. 10.23736/S0375-9393.24.18534-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coviello A, Iacovazzo C, Cirillo D, Bernasconi A, Marra A, Squillacioti F, Martone M, Garone E, Coppola F, de Siena AU, Vargas M, Servillo G (2024) Dexamethasone versus Dexmedetomidine as Adjuvants in Ultrasound Popliteal Sciatic Nerve Block for Hallux Valgus Surgery: A Mono-Centric Retrospective Comparative Study. Drug Des Devel Ther 17(18):1231–1245. 10.2147/DDDT.S442808. (PMID: 38645991; PMCID: PMC11032716) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material 1: Table S1. Secondary outcomes: Bromage and Hollmen scales of the healthy limb at different times.

Data Availability Statement

All data and related metadata underlying the findings reported in our study are provided as part of the submitted article. Additional data is available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.