Abstract

The incidence of Listeria species in raw whole milk from farm bulk tanks and from raw milk in storage at a Swedish dairy plant was studied. Listeria monocytogenes was found in 1.0% and Listeria innocua was found in 2.3% of the 294 farm bulk tank (farm tank) milk specimens. One farm tank specimen contained 60 CFU of L. monocytogenes ml−1. L. monocytogenes was detected in 19.6% and L. innocua was detected in 8.5% of the milk specimens from the silo receiving tanks at the dairy (dairy silos). More dairy silo specimens were positive for both Listeria species during winter than during summer. Restriction enzyme analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis were applied to 65 isolates of L. monocytogenes, resulting in 16 different clonal types. Two clonal types were shared by the farm tank milk and the dairy silo milk. All except one clonal type belonged to serovar 1/2a. In the dairy silo milk five clonal types were found more frequently and for a longer period than the others. No Listeria species were found in any other samples from the plant.

Outbreaks of listeriosis have been related to the consumption of dairy products, such as Swiss soft cheese, Mexican-style soft cheese, chocolate milk, and butter (3, 9, 19, 21, 22). Listeria spp. have been found in different places in the environment of dairy plants (20, 25, 27), and the bacteria may also survive for a long time in a dairy. Unnerstad et al. (33) found the same clonal type of Listeria monocytogenes persisting in a dairy plant for 7 years. To trace the sources of contamination in a food processing plant, characterization of the strain by discriminative typing methods is necessary. Serotyping as well as phage typing can be used as a routine method (18), but additional typing methods are often applied to further discriminate isolates. Different typing methods such as multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (11, 14), ribotyping (1), and plasmid profiling (12) have been applied to raw milk isolates of L. monocytogenes. Restriction enzyme analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) have been used to characterize dairy isolates (24, 33). However, reports of restriction enzyme analysis and PFGE characterization of raw milk isolates are rarely found in the literature (J. Harvey and A. Gilmour, ISOPOL XIII, Halifax, Canada, abstr. 69, 1998).

The aim of the present study was to investigate the occurrence of L. monocytogenes in raw whole milk from farm bulk tanks (farm tanks) and receiving tanks at the dairy plant (dairy silos), to characterize the isolates, and to assess the diversity of clonal types present.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Raw whole milk specimens from farm tanks.

From December 1997 to March 1998 one sample was collected from the farm tank of each of 153 farms, about one-third of the farms that deliver milk to the investigated dairy plant. The same farms, except for 12, were sampled from August to September 1998 (grazing period). The loss of 12 farms in the second investigation was due to the fact that some of the farms were no longer milk producers and some had converted to organic farming and were delivering their milk to another plant. Milk was collected aseptically from the farm tanks in 100-ml sterile plastic bottles at the same time as the milk was collected for transfer to the plant. In the farm tanks, the milk is constantly stirred and kept at +4°C. The samples were transported to the laboratory at +4°C and analyzed within 48 h.

Raw whole milk specimens from the dairy silos.

The dairy plant has three silos for raw whole milk: silos 1 and 2 have a volume of 40,000 liters each, and silo 3 has a volume of 100,000 liters. Raw milk specimens were collected and analyzed once or twice a week for 18 months, from November 1996 to April 1998, except in March 1997 and July 1997. About 100 ml of raw whole milk was sampled from the sampling cock on each of the three dairy silos, and 25 ml was used for analysis. Altogether 295 specimens were analyzed.

Samples from equipment at the dairy plant.

In March 1998 a survey of the equipment was performed. On this occasion two surface samples were taken with sterile cotton wool swabs on approximately 10 cm2 of the plates when the plate cooler was disassembled. Also eight gaskets of varied size from the plate cooler and the two silo pumps were analyzed in their entirety. The swabs were transferred to sterile flasks containing 25 ml of neutralizing buffer (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). The gaskets were transported to the laboratory dry in sterile stomacher bags. All samples were transported and kept cool at +8°C until analysis. In February and March 1998, specimens of 1 liter of rinse water were collected from the sampling cocks of the dairy silos after cleaning of the process equipment. Three rinse-water specimens were taken from silo 1, and two specimens were taken from each of silos 2 and 3. Before sampling, at least 1 liter of milk and water, respectively, was discharged.

Detection and identification of Listeria spp.

Raw whole milk specimens and samples from equipment were analyzed according to the method of the International Organization for Standardization (17) with some modifications. PALCAM Listeria Selective agar (Oxoid Unipath Ltd., Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom; PALCAM agar base CM877 and supplement SR150E) was the only selective solid medium used, and plating out was performed after the secondary enrichment only (34). Listeria organisms in the farm tank milk specimens were quantified by plating 0.1 ml of milk onto PALCAM Listeria Selective agar. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C, and presumptive Listeria colonies were counted. The International Organization for Standardization method was applied directly to 25-ml specimens of the raw whole milk. The rinse water (1 liter) was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.), and the filter was placed in the preenrichment broth together with 25 ml of sterile peptone water. Gaskets were analyzed in their entirety, and peptone water was added to adjust the weight to 25 g. Swabs with the neutralizing buffer were incubated in the preenrichment broth. Presumptive Listeria spp. were confirmed by picking five colonies, or all when fewer, and investigating the colonies for catalase reaction, Gram stain, hemolysis, and carbohydrate utilization. Isolates with doubtful hemolysis results were confirmed with the commercial probe AccuProbe (Gen-Probe, San Diego, Calif.). One L. monocytogenes isolate from each of the positive qualitative tests and all isolates from the quantitative tests were freeze-stored awaiting further analysis (−80°C in 80% [vol/vol] brain heart infusion broth and 20% [vol/vol] glycerol).

Product and drain samples.

Products and drains were sampled each week as part of the regulatory quality program of the plant during the same period in which the silos were sampled. This resulted in 440 surface samples of blue mold cheese, 70 whey samples, 149 swab samples of drains from the area where the pasteurized product is exposed to the room environment, and 116 samples of cheese-washing liquid. From all samples 25 g was analyzed with the Listeria Rapid Test (Oxoid Unipath Ltd.) (R. Holbrook, T. Briggs, J. Anderson, J. Blades, and P. N. Sheard, 81st Annu. Meet. Int. Assoc. Milk Food Environ. Sanitarians, San Antonio, Tex. 1994).

Preparation and cleavage of genomic DNA.

The method of preparation and cleavage is based on the method of Brosch et al. (6) and the Pharmacia LKB (Uppsala, Sweden) biotechnology protocol for preparing Escherichia coli DNA. L. monocytogenes strains were cultured on blood agar (Oxoid CM55, 5% horse blood) at 37°C for 24 h. One isolated colony was transferred to 10 ml of brain heart infusion broth (Oxoid CM225) and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C), washed twice in 10 ml of Pett IV (10 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.6], 1 M NaCl), and resuspended in 2.4 ml of the same buffer. Of the suspension, 0.5 ml was transferred to an Eppendorf tube, heated to 40°C, and mixed with an equal amount of 1% low-melting-temperature agarose (In Cert agarose; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) kept at the same temperature. The mixture was poured into the slots of a plastic mold (Gene Navigator; Pharmacia Biotech). The agarose plugs so formed were transferred to sterile Eppendorf tubes containing 1 ml of lysozyme buffer (3 mg of lysozyme ml−1 in 0.1 M phosphate buffer [pH 7] with 20% sucrose). Cell lysis was achieved by incubating the plugs in the buffer overnight at 37°C. The plugs were washed once in TE buffer (20 mmol of Tris HCl liter−1, 50 mmol of EDTA liter−1, pH 8.0). The TE buffer was then replaced with 1 ml of proteolysis buffer (0.05 mol of EDTA liter−1 [pH 8], 1% [wt/vol] N-lauroylsarcosine (Sigma), 200 mg of pronase E ml−1 [Boehringer Mannheim]). Proteolysis was carried out at 55°C for 48 h. Before restriction cleavage a 2-mm slice of each plug was washed three times in TE buffer and incubated for 2 h at 50°C in 200 μl of Pefablock (0.35 mg ml−1 [Boehringer Mannheim] in TE buffer), and again the plugs were washed three times in TE. Plugs were then incubated overnight in a solution consisting of 115 μl of restriction buffer; 868 μl of Milli-Q water; 10 μl of acetylated bovine serum albumin (10 mg ml−1; Promega, Madison, Wis.); 100 μl of buffer A (10× concentration; Boehringer Mannheim); and 22 μl of SmaI or ApaI (all enzymes at 10 U/ml; SmaI and ApaI from Boehringer Mannheim and AscI from New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.). The buffer used for restriction with the AscI enzyme contained 110 μl of NE buffer 4 (10× concentration; New England Biolabs) instead of buffer A and 12 μl of AscI. Restriction was carried out at 37°C for AscI, at 30°C for ApaI, and at 25°C for SmaI. The next day the restriction buffer was replaced with 0.5× TBE buffer (5× TBE, 89 mmol of Tris base liter−1, 89 mmol of boric acid liter−1, 2 mmol of EDTA liter−1, pH 8) for 1 h, then cast in a 1.2% agarose gel (Seakem Gold agarose; FMC BioProducts) in 0.5× TBE buffer, and run in a Pharmacia Gene Navigator. For AscI and ApaI the migration period was 24 h at 200 V and initial and final pulse times were 4.0 and 40.0 s, respectively; for SmaI, the migration period was 10 h at 300 V and the pulse time was 9 s. For both programs the circulating buffer (0.5× TBE) was kept at 8°C. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide (1 μg ml−1) for 20 min, washed in 0.5× TBE, and photographed over a 312-nm transilluminator. The photographs were analyzed visually and with Molecular Analyst Software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). Pearson correlation was used, and for optimization, fine alignment was 1%. The clustering method was the unweighted pair group method using arithmetic averages. Lambda ladder PFGE Marker 340 (New England Biolabs) was used as molecular weight markers. Each strain was tested at least twice with each enzyme. Isolates were considered to belong to the same clonal type if all patterns obtained with the described method were indistinguishable with all three enzymes.

Serotyping.

Serotyping was performed on isolates representing different clonal types according to a reference method (30).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Farm tank milk (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Number of milk specimens from farm tanks and frequency of L. monocytogenes and L. innocua

| Period | No. of samples (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Positive for species:

|

Total positive | ||

| L. monocytogenes | L. innocua | |||

| December-March | 153 | 2 (1.3) | 4 (2.6) | 6 (3.9) |

| August-September | 141 | 1 (0.7) | 3 (2.1) | 4 (2.8) |

| Total | 294 | 3 (1.0) | 7 (2.3) | 10 (3.4) |

L. monocytogenes was isolated from only three (1%) of the milk specimens from farm tanks. The incidence found in the present study is close to results obtained in investigations performed in other countries (10).

Of the two milk specimens harboring L. monocytogenes in the first sampling period, one contained <10 CFU of L. monocytogenes ml−1 and the other contained 60 CFU of L. monocytogenes ml−1. In all specimens the level of Listeria innocua was <10 CFU ml−1. At the second sampling time (August to September) all specimens contained <10 CFU of Listeria spp. ml−1. Only one farm was positive for Listeria spp. on both occasions. On the farm where 60 CFU of L. monocytogenes ml−1 was detected during the indoor season, L. innocua was detected during the outdoor season. A higher incidence of Listeria spp. during spring has been reported from studies of raw milk in farm tanks (for a review see reference 28).

Dairy silo milk (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Number of milk specimens from dairy silos 1, 2, and 3 and frequency of L. monocytogenes and L. innocua

| Silo | No. of samples (%)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tested | Positive for species:

|

||

| L. monocytogenes | L. innocua | ||

| 1 | 97 | 27 (27.8) | 7 (7.2) |

| 2 | 98 | 16 (16.3) | 7 (7.1) |

| 3 | 100 | 15 (15.0) | 11 (11.0) |

| Total | 295 | 58 (19.6) | 25 (8.5) |

The incidence of L. monocytogenes in the dairy silo milk was higher than that in the farm tank milk. Theoretically only one transport of L. monocytogenes in contaminated milk at a time is needed to keep the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in the silo tanks high.

L. monocytogenes bacteria were found in the raw whole milk from all three dairy silos. In dairy silo 1 the frequency was 27.8%, which was about twice the frequency in the other two dairy silos. The higher frequency in dairy silo 1 could be due either to a persistent contamination in the silo or to the fact that this silo, by coincidence, was the recipient of most of the contaminated raw milk. In the present study, L. monocytogenes was found in all three silos every tested month during the period of investigation (Table 3). The incidence was slightly higher during January to March than during the other months of the year. L. innocua was found at a frequency of 7.1 to 11.0%. Why the frequency of L. innocua was twice that of L. monocytogenes in the farm tanks and the opposite in the dairy silos in the present study is unclear. The milk in the dairy silos was stored longer than that in the farm tanks before the samples were taken. It might be possible that the lactoperoxidase system of the raw milk affects L. innocua even more than L. monocytogenes (26). However, to our knowledge this has not been investigated. The detected level of Listeria spp. in raw whole milk from dairy silos varies in different studies; this may possibly be due to the age and storage conditions of the milk at sampling. Canillac and Mourey (7) detected no L. monocytogenes but found L. innocua in 25% of the raw whole milk specimens. Harvey and Gilmour (13) reported a 33.3% incidence of L. monocytogenes (54.0% for Listeria spp.) in raw whole milk from dairy silos.

TABLE 3.

Distribution of clonal types of L. monocytogenes (A to O) found in milk from the three dairy silos and frequency of L. innocua

| Mo and part of moa | Result for silo:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Nov. 1996 | |||

| 1 | L. innocua | A | |

| 2 | G | A | |

| 3 | L. innocua | ||

| 4 | |||

| Dec. 1996 | |||

| 1 | L. innocua | A | |

| 2 | A | ||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| Jan. 1997 | |||

| 1 | C | ||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | M | E | |

| 4 | A | A | L. innocua |

| Feb. 1997 | |||

| 1 | A | ||

| 2 | A | L. innocua | |

| 3 | E | ||

| 4 | A, C | B | H |

| Mar. 1997b | |||

| Apr. 1997 | |||

| 1 | C | B | |

| 2 | B | A | C |

| 3 | |||

| 4 | L. innocua | ||

| May 1997 | |||

| 1 | B | ||

| 2 | L. innocua | ||

| 3 | L. innocua | ||

| 4 | |||

| June 1997 | |||

| 1 | B | D | |

| 2 | E | L. innocua | |

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| July 1997b | |||

| Aug. 1997 | |||

| 1 | D | ||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | L. innocua | ||

| 4 | E | D | |

| Sept. 1997 | |||

| 1 | D | ||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | E | ||

| 4 | |||

| Oct. 1997 | |||

| 1 | L. innocua | D | |

| 2 | E | ||

| 3 | F | ||

| 4 | |||

| Nov. 1997 | |||

| 1 | N | ||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | L. innocua | ||

| 4 | D | ||

| Dec. 1997 | |||

| 1 | L. innocua | ||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4 | |||

| Jan. 1998 | |||

| 1 | |||

| 2 | F | L. innocua | L. innocua |

| 3 | J | O | |

| 4 | K | L | J, J |

| Feb. 1998 | |||

| 1 | K | L. innocua | L. innocua |

| 2 | L. innocua | B | |

| 3 | F | ||

| 4 | F | J | |

| Mar. 1998 | |||

| 1 | L. innocua | L. innocua | |

| 2 | J, L. innocua | ||

| 3 | J | L. innocua | |

| 4 | F | J | I |

| Apr. 1998 | |||

| 1 | F | J | |

| 2 | L. innocua | J | I |

| 3 | J | ||

| 4 | |||

Jan., January; Feb., February; Mar., March; Apr., April; Aug., August; Sept., September; Oct., October; Nov., November; Dec., December. Each month is divided into four parts.

Samples were not taken in March and July 1997.

Clonal types.

Restriction enzyme analysis and PFGE applied to the L. monocytogenes isolates from farm tanks and the 58 L. monocytogenes isolates from dairy silos resulted in 16 different clonal types. The different clonal types found in the raw milk from the dairy silos and the farm tanks have been designated with the letters A to P. Clonal types D and O were found in the farm tank milk as well as in the dairy silos. Clonal type P was found only in the farm tank milk. From the farm sample that contained 60 CFU of L. monocytogenes ml−1 five isolates were investigated, and all were of the same clonal type (O).

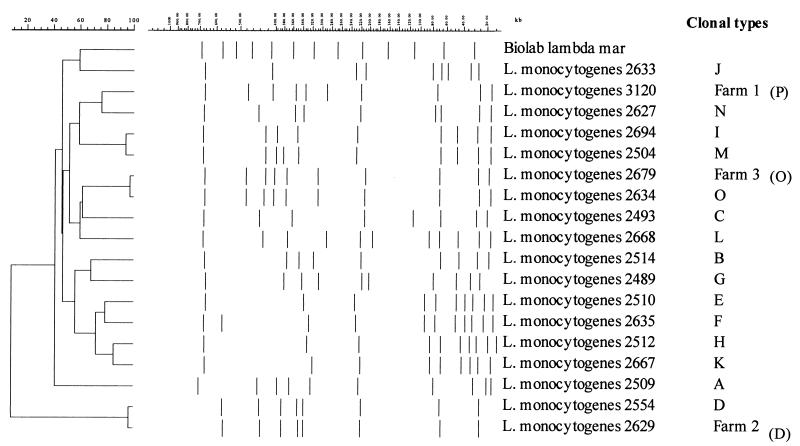

The patterns (AscI) of the different clonal types are shown in the cluster correlation figure (Fig. 1). The clonal types K and H and types I and M, respectively, correlate at the level of 90% or more with the enzymes used. There is only a slight difference between these strains, usually only a one-band difference. It appears that the clonal types E, H, and K are identical, but there is a difference between the strains when the other enzymes are used. We consider the clonal types E, H, and K closely related (32). One isolate representing each clonal type was serotyped; clonal type G belonged to serovar 1/2b, and all the other clonal types belonged to serovar 1/2a.

FIG. 1.

Restriction enzyme analysis band patterns from AscI cleavage of chromosomal DNA of L. monocytogenes strains isolated from farm tank and silo milk.

Arimi et al. (1) studied the diversity of Listeria ribotypes isolated from different farm and dairy-related environments. They suggested that the raw milk is contaminated by numerous Listeria ribotypes endemic to the farm environment. In the present study, the clonal types A, B, D, E, F, and J were found several times over a period of several months (Table 3). The longest period is recorded for clonal type E, which was found six times during a 10-month period. The source of this clonal type could be the udder of a cow with subclinical mastitis, as a period of 10 months is in agreement with the lactation period of a cow (Tetra Pak dairy processing handbook; Tetra Pak Processing Systems AB, Lund, Sweden). There might also be a persistent contamination in, for example, the farm tank (13, 29, 31, 35).

Dairy plant and equipment.

When the milk arrives at the dairy plant, milk from a certain farm is usually always pumped into the same dairy silo. This may explain why a certain clonal type is often found in the same dairy silo (Table 3). Another explanation might be that the pipes or dairy silos get contaminated and that it sometimes takes several weeks for the Listeria bacteria to be washed out. The cleaning-in-place program for the dairy silos and piping at the investigated dairy plant consisted of rinsing with water and then use of alkaline detergent (SU 224; DiverseyLever; 20 g liter−1) at 68°C for 20 min, followed by rinsing. It has been shown elsewhere that L. monocytogenes can attach not only to stainless steel surfaces but also to rubber, glass, and polypropylene (15, 23) and grow as a biofilm (4). Arizcun et al. (2) investigated decontamination procedures to remove L. monocytogenes growing in biofilms on glass surfaces. A time-temperature treatment of 63°C for 30 min resulted in a decline of 5.5 log units in biofilm population. Thus, theoretically, the cleaning-in-place program at the plant would remove a possible biofilm formation on the surfaces in the piping or tanks. The fact that all of the samples in the present study taken from the equipment (rinse water, swabs, and gaskets) were negative for Listeria spp. supports this statement. All product and drain samples in the present study were negative for Listeria spp. However, the Listeria Rapid Test was used for these samples and may be less efficient than the culture method (5).

The kettle milk at the investigated dairy plant is pasteurized at 73°C for 15 s (flow diversion valve temperature, 70.4°C), and the production area is segregated as a high-risk area from the area of raw milk reception (16). These measures seem to be efficient, as all product and drain samples taken to ensure product quality during the period were negative for Listeria spp. In other investigations in dairies, Listeria spp. have been found at a high frequency on floors and in drains (8, 20). They have also been found on machinery in the dairy process area, e.g., on presses and conveyor belts (25), and in the cheese ripening area, especially in the brushing machines (7).

The present and previous studies (7, 13) illustrate that Listeria spp. are very likely to be present in raw milk at the dairy and thus present a hazard for further contamination of the dairy plant and dairy products if strict hygiene measures are not enforced.

Acknowledgments

We express thanks to Jacques Bille and Elizabeth Bannerman at Centre National des Listeria, Institut de Microbiologie, Lausanne, Switzerland, for serotyping the strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arimi, S. M., E. T. Ryser, T. J. Pritchard, and C. W. Donnelly. 1997. Diversity of Listeria ribotypes from dairy cattle, silage and dairy processing environments. J. Food Prot. 60:811-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arizcun, C., C. Vasseur, and J. C. Labadie. 1998. Effect of several decontamination procedures on Listeria monocytogenes growing in biofilms. J. Food Prot. 61:731-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bille, J., and M. P. Glauser. 1988. Zur Listeriose-Situation in der Schweitz. Bull. Bundesamtes Gesundheitswesen 3:28-29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackman, I. C., and J. F. Frank. 1996. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes as a biofilm on various food-processing surfaces. J. Food Prot. 59:827-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco, M. M., J. F. Fernández-Garayzábal, C. Cabrero, J. Alemany, and L. Dominguez. 1998. Comparison between two commercial ELISAs and a culture procedure for the detection of Listeria spp. Z. Lebensm.-Unters. -Forsch. 206:148-150. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brosch, R., C. Buchrieser, and J. Rocourt. 1991. Subtyping of Listeria monocytogenes serovar 4 b by use of low-frequency-cleavage restriction endonucleases and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Res. Microbiol. 142:667-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canillac, N., and A. Mourey. 1993. Sources of contamination by Listeria during the making of semi-soft surface-ripened cheese. Sci. Aliments 13:533-544. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charlton, B. R., H. Kinde, and L. H. Jensen. 1989. Environmental survey for Listeria species in California milk processing plants. J. Food Prot. 3:198-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dalton, C.-B., C. C. Austin, J. Sobel, P. S. Hayes, W. F. Bibb, L. M. Graves, B. Swaminathan, M. E. Proctor, and P. M. Griffin. 1997. An outbreak of gastroenteritis and fever due to L. monocytogenes in milk. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:100-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donnelly, C. W. 2001. Factors associated with hygienic control and quality of cheeses prepared from raw milk: a review. Bull. IDF 369:16-27. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenlon, D. R., T. Stewart, and W. Donachie. 1995. The incidence, number and types of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from farm bulk silos. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 20:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fistrovici, E., and D. L. Collins-Thompson. 1990. Use of plasmid profiles and restriction endonuclease digest in environmental studies of Listeria spp. from raw milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 10:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey, J., and A. Gilmour. 1992. Occurrence of Listeria species in raw milk and dairy products produced in Northern Ireland. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 72:119-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey, J., and A. Gilmour. 1994. Application of multilocus enzyme electrophoresis and restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis to the typing of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from raw milk, nondairy foods, and clinical and veterinary sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1547-1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herald, P. J., and E. A. Zottola. 1988. Attachment of Listeria monocytogenes to stainless steel surfaces at various temperatures and pH values. J. Food Sci. 53:1549-1552, 1562. [Google Scholar]

- 16.International Dairy Federation. 1997. Bulletin of the International Dairy Federation, no. 324. International Dairy Federation, Brussels, Belgium.

- 17.International Organization for Standardization. 1995. ISO draft international standard ISO/DIS 11290-1. International Organization for Standardization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 18.Jacquet, C., J. Rocourt, and A. Reynaud. 1993. Study of Listeria monocytogenes contamination in a dairy plant and characterization of the strains isolated. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 20:13-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James, S. M., S. L. Fannin, B. A. Agee, B. Hall, E. Parker, J. Vogt, G. Run, J. Williams, L. Lieb, C. Salminen, T. Pendergast, S. B. Werner, and J. Chin. 1985. Listeriosis outbreak associated with Mexican-style cheese—California. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 34:357-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klausner, R. B., and C. W. Donnelly. 1991. Environmental sources of Listeria and Yersinia in Vermont dairy plants. J. Food Prot. 54:607-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linnan, M. J., L. Mascola, X. D. Lou, V. Goulet, S. May, C. Salminen, D. W. Hird, M. L. Yonkura, P. Hayes, R. Weaver, A. Audrurier, B. D. Plikaytis, S. L. Fannin, A. Kleks, and C. V. Broome. 1988. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N. Engl. J. Med. 319:823-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyytikäinen, O., T. Autio, R. Maijala, P. Ruutu, J. T. Honkanen-Buzalski, M. Miettinen, M. Hatakka, J. Mikkola, V. Anttila, T. Johansson, L. Rantala, T. Aalto, H. Korkeala, and A. Siitonen. 1999. An outbreak of Listeria monocytogenes serotype 3a infections from butter in Finland. J. Infect. Dis. 181:1838-1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mafu, A. A., D. Roy, J. Goulet, and P. Magny. 1990. Attachment of Listeria monocytogenes to stainless steel, glass, polypropylene, and rubber surfaces after short contact times. J. Food Prot. 53:742-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Margolles, A., B. Mayo, and C. G. de los Reyes-Gavilán. 1998. Polymorphism of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from short-ripened cheeses. J. Appl. Microbiol. 84:255-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menendez, S., M. R. Godinez, J. L. Rodriguez-Otero, and J. A. Centeno. 1997. Removal of Listeria spp. in a cheese factory. J. Food Safety 17:133-139. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitt, W. M., T. J. Harden, and R. R. Hull. 2000. Investigation of the antimicrobial activity of raw milk against several foodborne pathogens. Milchwissenschaft 55:249-252. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pritchard, T. J., K. J. Flanders, and C. W. Donnelly. 1995. Comparison of the incidence of Listeria on equipment versus environmental sites within dairy processing plants. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 26:375-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryser, E. T., and E. H. Marth. 1991. Listeria, listeriosis, and food safety, p. 294-296. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 29.Sanaa, M., B. Poutrel, J. L. Mannered, and F. Serieys. 1993. Risk factors associated with contamination of raw milk by Listeria monocytogenes in dairy farms. J. Dairy Sci. 76:2891-2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seeliger, H. P. R., and K. Höhne. 1979. Serotyping of Listeria monocytogenes and related species. Methods Microbiol. 13:33-46. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slade, P. J., E. C. Fistrovici, and D. L. Collins-Thompson. 1989. Persistence at source of Listeria spp. in raw milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 9:197-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unnerstad, H., E. Bannerman, J. Bille, M.-L. Danielsson-Tham, E. Waak, and W. Tham. 1996. Prolonged contamination of a dairy with Listeria monocytogenes. Neth. Milk Dairy J. 50:493-499. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waak, E., W. Tham, and M.-L. Danielsson-Tham. 1999. Comparison of the ISO and IDF methods for detection of Listeria monocytogenes in blue veined cheese. Int. Dairy J. 9:149-155. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoshida, T., Y. Kato, M. Sato, and K Hirai. 1998. Sources and routes of contamination of raw milk with Listeria monocytogenes and its control. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60:1165-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]