Abstract

Background

The maize inbred line Chang7-2 and derived lines are important male donors for hybrid production, contributing significantly to the development of high-yield and stress-tolerant hybrids. Additionally, Chang7-2 serves as a valuable model inbred line for genetic and genomic studies, facilitating the discovery of genes underlying hybrid vigor and other agronomic traits.

Results

Here, a reference genome assembly and a chemical-induced mutant population (N = 1,716) through ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) treatments are generated using Chang7-2. Each EMS line is whole genome sequenced and compared to the Chang7-2 genome, identifying 2,586,769 mutations with 4,939 mutations causing premature stop codons or altered splicing sites. The effect estimation of mutations using two large language artificial intelligence (AI) models, namely the protein language model ESM1b and the DNA language model PlantCaduceus, reveals 15,264 and 18,326 deleterious mutations, respectively. Mutation effects estimated with AI models accelerate revelation of four causal mutations underlying phenotypes of albino leaf, reduced cuticular wax, altered seed color, and male sterility. In addition, allelic expression quantification of genic mutations in 13 EMS M1 lines and their M2 heterozygous progeny, which contain both wildtype and mutant alleles, shows that mutant alleles are overall accumulated at a lower level compared to wildtype. Such allelic disparity is observed for some synonymous mutations, indicating they may not be biologically inconsequential.

Conclusions

AI-based estimation of mutation effects offers cross-species evidence for functional impacts of mutations. Our study demonstrates its application in revealing deleterious EMS mutations and identifying causal mutations responsible for mutant phenotypes.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13059-025-03890-2.

Keywords: Zea mays, Genome assembly, Mutation, EMS

Background

Maize is a staple crop worldwide. The species also serves as a model organism for essential research in fundamental biology and crop breeding. Many maize inbred lines have been established, preserving the high level of genetic diversity [1–4]. High-quality genome assemblies of diverse inbred lines provide resources for genetic improvement of maize [5–11]. The inbred line Chang7-2, established in 1986, is the best-known progeny of HuangZaoSi, which, in turn, represents a major maize germplasm heterotic group in China [12]. Due to the exceptional combining ability, resilience to drought and barren soil, high-level adaptability, and robust disease resistance, Chang7-2 and derived inbred lines are favorable male parents for hybrid lines, including the popular commercial hybrid ZhengDan 958 [13, 14]. Chang7-2, in itself, is an important model inbred for genetic and genomic studies, and a draft genome assembly of Chang7-2 has been generated [12].

Mutagenesis is a general approach for studying genetic variation. In maize, Mutator transposon tagging has been used to create the mutant stocks, UniformMu, BonnMu, and ChinaMu [15–18]. Mutator tagging has provided tens of thousands of knockout mutants although Mutator transposon is preferred to be integrated at gene promoters or untranslated genic regions [16, 19, 20]. Ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS), a highly effective and less biased mutagen, has been used to mutagenize inbred line B73, producing hundreds of thousands of EMS characteristic point mutations from G/C to A/T [21].

Here we generated 1,716 EMS lines of Chang7-2 and performed whole genome sequencing for all these lines. A chromosome-level Chang7-2 reference genome was constructed to facilitate accurate identification of EMS mutations. The high-quality genome and genome annotation, along with a recently developed prediction tool using large language models (LLM), enabled classification of numerous EMS mutations to functionally impactive mutations.

Results

Chang7-2 genome assembly and annotation

A contig assembly of Chang7-2 was created from approximately 40x PacBio HiFi sequencing reads through Hifiasm [22], which produced 2.32 Gb of sequences consisting of 1,740 contigs, with the longest contig being 150.4 Mb and the N50 of 55.6 Mb (Additional file 1: Fig. S1, Additional file 2: Table S1). HiC data of Chang7-2 were then used to scaffold the assembled contigs with 3d-dna and Juicebox [23, 24], resulting in the final genome assembly (Chang7-2v1) of ten chromosome-level pseudomolecules (2.13 Gb) and unanchored contigs (Additional file 1: Fig. S2, Additional file 2:Table S2). The repeat and transposable element annotation identified approximately repetitive DNA content of 86% with 70% long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (Additional file 2: Table S3). RNA-seq data of ten diverse tissues (Additional file 2: Table S4) were generated to facilitate gene annotation, which was conducted with an integrated pipeline [8]. Gene annotation resulted in the annotation version of Chang7-2v1a with 39,702 well-evidenced genes and 93,689 transcripts. The gene annotation includes 20,556 genes with a single isoform and two genes that each have the highest number of isoforms, with 26 isoforms per gene (Additional file 2: Table S5). BUSCO transcriptomic analysis showed the Chang7-2 gene annotation covers 97.5% (3,155/3,236) of Liliopsida conserved genes [25].

PacBio HiFi sequencing data were used to identify the 5-methylcytosine modification at CG sites. In total, 87.7% of 93.15 millions of CG sites were heavily methylated. The methylation level progressively increased from two arms of each chromosome to the centromere (Fig. 1). Most of CG methylation sites (92.1%) were in intergenic regions. and 4.1% were in gene body regions. The CG methylation was detected in 67.3% (N = 26,357) of genes, and most genes had less than 10 CG methylation sites per kb. Genic CG methylation sites were largely located within the gene body, with a pronounced reduction around translation start and end sites (Additional file 1: Fig. S3).

Fig. 1.

Circos plot of genomic features. Density of genes (A), repeat densities (B), Ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) mutants per Mb (C), average CG cytosine methylation levels per Mb (E) were plotted. D Syntenic regions with B73 larger than 200 kb and inversion regions larger than 50 kb were colored with gray and green, respectively

Comparative genomic analysis identified unique inversions in Chang7-2

The Chang7-2 genome sequences were compared with a collection of chromosome-level genomes of maize inbred lines, including B73, A188, Mo17, and additional twenty-five founders of the Nested Association Mapping (NAM) populations [5, 7, 8]. The Nucmer genome alignment tool and the structural variation pipeline Syri were used to identify syntenic blocks and structural variation [26, 27]. On average, 50% of chromosomal regions in Chang7-2 exhibit synteny with the other inbred lines (Additional file 2: Table S6). Approximately 3.8 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 0.6 insertion or deletion (INDEL) events per kilobase were observed in the syntenic blocks (Additional file 2: Table S6). The top 15 largest syntenic blocks are from comparisons with Mo17, Oh43, B97, Ms71, M162W and B73. Megabase-level large syntenic blocks exhibited a low level of DNA polymorphisms, and 9 out of 15 lay within 20 Mb around the centromeres. (Additional file 1: Fig. S4, Additional file 2: Table S7). At the gene level, approximately 65% of Chang7-2 genes were syntenic to B73v5 genes. Similar levels of syntenic gene pairs were found with the other inbred lines (Additional file 2: Table S8).

Structural variation analysis found inversions, translocations, copy number variations, and unaligned Chang7-2 sequences (Fig. 2, Additional file 2: Table S9). The unaligned Chang7-2 sequences presumably are absent in other maize lines or represent complex sequences possibly found in intractable repetitive regions. Notably, forty large inverted regions were found in Chang7-2v1 as compared with the 28 maize inbred lines. The largest event is 26.7 Mb in size and is located on the long arm of chromosome 2, from 94.5 Mb to 121.2 Mb. Genomes from CML322, Il14H, Oh7B, and P39 also possess this large inversion. Two inversions are unique to Chang7-2 (Additional file 2: Table S10). One Chang7-2-specific inversion (INV_29) spans approximately 4.4 Mb at around from 51 to 55 Mb on chromosome 6 and is near the centromere. The other Chang7-2-specific inversion (INV_2) is 25 Mb and located from the 228 Mb to 253 Mb in chromosome 1 of Chang7-2v1. The INV_2 interval was fully covered by a long recombination-suppression region in a recombinant inbred line (RIL) population developed from the cross between Chang7-2 and another maize inbred line Zheng58 (Additional file 1: Fig. S5), supporting the inversion of the INV_2 region between Chang7-2 and Zheng58 [28, 29]. The INV_2 region overlapped with a plant height quantitative trait locus (QTL) and an ear height QTL identified from the Zhang58 x Chang7-2 RIL population, of which the Chang7-2 allele positively contributed to the height [29]. On average 56.7% sequences of INV_2 were classified as highly divergent between Chang7-2 and all 28 maize inbreds. INV_2, therefore, may represent an ancient inversion event. The B73 and Chang7-2 regions of INV_2 contained 518 and 515 genes, respectively. Of these, 342 genes were syntenic, although arranged in largely reverse order. The proportion of syntenic genes in INV_2 was not significantly different from that in the genomic regions outside of INV_2 ( test, p-value = 0.503 for B73 and p-value = 0.418 for Chang7-2 genes). The composition of repetitive sequences was also similar between the two inverted regions (Additional file 2: Table S11).

test, p-value = 0.503 for B73 and p-value = 0.418 for Chang7-2 genes). The composition of repetitive sequences was also similar between the two inverted regions (Additional file 2: Table S11).

Fig. 2.

Visual summary of genomic comparisons of chromosome 1. A Chromosome 1 comparison between B73 and Chang7-2. Blue and red regions on chromosomes represent unaligned and highly divergent regions. B Distributions of synteny (gray), inversion (green), translocation (orange), copy number variation (purple), and unaligned regions (blue) of Chang7-2 sequences as compared with other maize inbred lines on chromosome 1

Construction of Chang7-2 EMS mutants and detection of EMS mutations

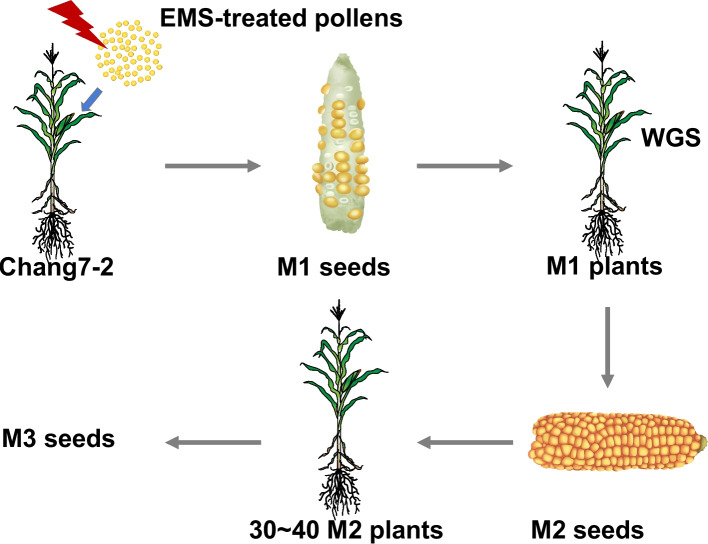

Chang7-2 pollen was treated with EMS and used to pollinate Chang7-2 wildtype plants. Approximately 2,000 M1 seeds were germinated and self-pollinated to generate M2 seeds (Fig. 3). Leaves of 1,802 M1 plants that successfully produced M2 seeds were used for DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing (WGS), of which 1,716 were maintained. Multiple visible traits were phenotyped for 1,063 families of M2 seeds, seedlings, and mature plants (Additional file 2: Table S12, Additional file 1: Fig. S6). Seed related phenotypes included mutants with small kernels, defective kernels, embryo-related mutations, the pale-yellow color, opaque and vivipary. Seedling phenotypes included albinism, yellowing, and glossy, accounting for 9.12% of 1,063 M2 families. Mature plant phenotypes included male sterility, female sterility, and lesion mimicry, which, in total, were observed in 7.24% of M2 families (Additional file 2: Table S12).

Fig. 3.

EMS mutagenesis of Chang7-2 and the mutant collection. Ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) treated Chang7-2 pollens were pollinated with Chang7-2 wildtype plants. M1 plants were self-pollinated to generate M2 seeds. Leaves of M1 plants were used for DNA extraction and whole genome sequencing (WGS) for detection of EMS mutations. M2 plants were self-pollinated to bulk M3 seeds

Approximately 25x whole genome sequencing (WGS) data were generated for each of seven M1 lines to assess the depth requirement for accurate read calls. Stringent criteria were used to identify polymorphic sites, which served as the ground truth for EMS mutant sites. We then downsampled WGS reads for EMS mutation validation. At least 70% of the mutations could be reliably identified using WGS of 10x sequencing depth, and the accuracy of the mutation discovery was estimated to be up to 78% for the seven test M1 lines (Additional file 2: Table S13). Accuracy was higher when a higher number of EMS mutations occurred in a line. Approximately 10x WGS data was generated for each of the 1716 EMS M1. The 1,716 EMS lines harbored 2,586,769 non-redundant mutations, ranging from 502 to 9,193 EMS mutations per EMS line (Additional file 2: Table S14). The EMS mutations were uniformly distributed in the genome and most EMS mutations were located in the intergenic (48.8%) or intron (15.0%) regions (Fig. 1E, Additional file 2: Table S15). The distribution of the levels of CG methylation at EMS mutation sites (N = 43,207) is highly similar to the distribution of the methylation levels at CG sites with no EMS mutations, indicative of no obvious connection between EMS mutation and cytosine methylation (Additional file 1: Fig. S7). One hundred and thirty-three mutations from 86 M1 EMS lines were selected for the validation. The EMS mutations selected for the validation were from 117 genes, including 62 premature stop codon gain mutations, 32 missense mutations, 31 mutations affecting splicing, and a few other types of mutations (Additional file 2: Table S16). PCR and Sanger sequencing of genomic DNAs from M2 of M3 family seedlings showed that 84% (113/133) mutations were recovered in homozygous or heterozygous forms (Additional file 2: Table S17). EMS mutants are available to order through the website https://maizedb.rmbreeding.cn. EMS mutations can be searched through inputting a gene model name or a genomic interval in the Chang7-2 genome. The website also allows users to search B73 gene models directly to identify EMS mutations on Chang7-2 homologous genes.

Annotation of EMS mutations to identify deleterious mutations

Potential functional impacts of EMS mutations were evaluated with SNPEff [30]. While the majority (96%) of the mutations were on non-coding sequences or synonymous substitutions, 4,939 EMS mutations of the original 2,586,769 were annotated to have high impacts on 4,240 genes (Additional file 2: Table S18). Among these, 596 genes had two or more EMS mutations. Genes with multiple mutations are associated with large gene size (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). Four genes, namely Zm00091aa003120, Zm00091aa006099, Zm00091aa029947, and Zm00091aa034435, carried the most mutations (N = 5). All these four genes are at least 12 kb in length. More than half of 4,939 mutations introduced premature stop codons. On average, each M2 family carried approximately 2–3 functionally high-impact mutations.

SNPEff analysis identified 55,615 EMS mutations causing single amino acid missense changes in encoded proteins of 23,337 genes. To refine the estimation of impacts due to missense mutations, the missense effect prediction ESM1b model, which is a large protein language model used to evaluate functional effects of human protein variants [31]. A curated Arabidopsis dataset including 2,910 mutations with detectable phenotypic changes and 1,583 neutral SNPs was used to evaluate the model performance for plant data. The method scores a variant effect for each missense mutation, the log-likelihood ratio (LLR) between the variant and the wildtype residue. A small negative LLR score (e.g., less than −7.5) indicates a predicted deleterious impact on protein function. Using the ESM1b LLR score cutoff of −7.5, the prediction precision was 97.2%, and the recall rate, or the detection rate, was 78.6% (Additional file 2: Table S19). The method with a high precision allows for accurate identification of deleterious missense EMS mutations.

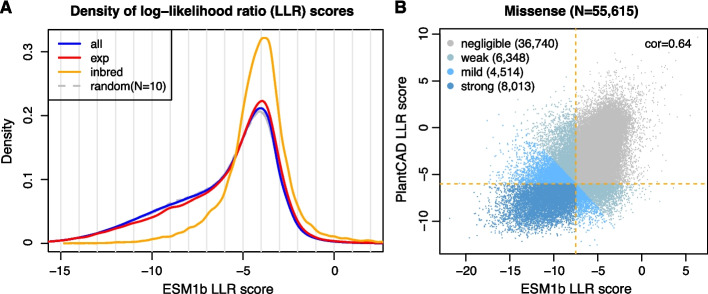

The prediction of 55,615 mutations detected from Chang7-2 EMS mutants at LLR scores peaked at around −4 (Fig. 4), indicating that most EMS missense mutations exhibited low or neutral impacts on protein function. Using the LLR score cutoff of −7.5, 15,264 predicted deleterious missense EMS mutations occurred in 9,602 genes. The LLR scores of all possible simulated EMS-type missense mutations in Chang7-2 revealed a LLR score distribution with a slightly higher proportion of deleterious missense EMS mutations (Fig. 4A). Many fewer deleterious mutations were predicted for native SNPs in the syntenic regions between Chang7-2 and other maize inbred lines. Overall, the fitness selection for missense EMS mutations in the heterozygous form in M1 plants appears to be weak. In contrast, naturally occurring missense alterations were subjected to a much stronger selection in inbred line populations.

Fig. 4.

Density of variant effect scores of EMS mutants using large language models. A The blue curve represents the density of variant effect, or LLR, scores of all possible Ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) mutations (all). The red curve represents the density of LLR scores of experimentally collected EMS mutations (exp). Dashed gray curves represent the density of randomly selected EMS-type mutants with an equal number to those of the experimental mutation set (random). Ten dashed curves were plotted from 10 repeated random selections. The orange curve represents the density of a set of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on syntenic regions between Chang7-2 and other maize inbred lines (inbred). B Scatterplot between ESM1b LLR scores and the LLR scores from PlantCAD. cor: correlation coefficient

The large DNA language model PlantCaduceus, or PlantCAD, was used to estimate functional effects of all EMS mutations, including missense mutations [32]. A similar LLR score was determined for each mutation. The same curated Arabidopsis missense mutation dataset was used to evaluate the performance of PlantCAD. The effect estimation between PlantCAD and ESM1b was highly consistent (Additional file 1: Fig. S9, Additional file 2: Table S20). Using the LLR score cutoff of −6, the prediction precision was 88.2%, and the recall rate was 86.4% (Additional file 2: Table S19). The PlantCAD LLR score less than −6 was therefore applied to identify 18,326 deleterious EMS mutations, including 4,028 deleterious EMS mutations on non-coding regions or causing synonymous amino acid changes whose effects could not be estimated by either SNPEff or ESM1b (Fig. 4B, Additional file 2: Table S21).

To understand the reliability of using the LLR thresholds of −7.5 and −6 for predicting maize deleterious mutations with ESM1b and PlantCAD, respectively. We created a Maize Missense Mutation Database (v0.3), 3MD, including 54 missense deleterious mutations causing visible mutant phenotypes (Additional file 2: Table S22). As a control, 54 SNPs in Chang7-2 regions syntenic with the genomes of maize inbred lines, A188, Mo17 and 26 NAM parents were randomly selected and referred to as non-deleterious missense mutations. Both ESM1b and PlantCAD predictions showed a very high precision (> 97%) (Additional file 2: Table S23, Table S24). The recall rate using ESM1b was 90.7%. However, the recall rate using PlantCAD was relatively low (68.8%). The result indicated the deleterious maize missense mutations identified by either of the two models are reliable, and some deleterious mutants may be overlooked by using only one model.

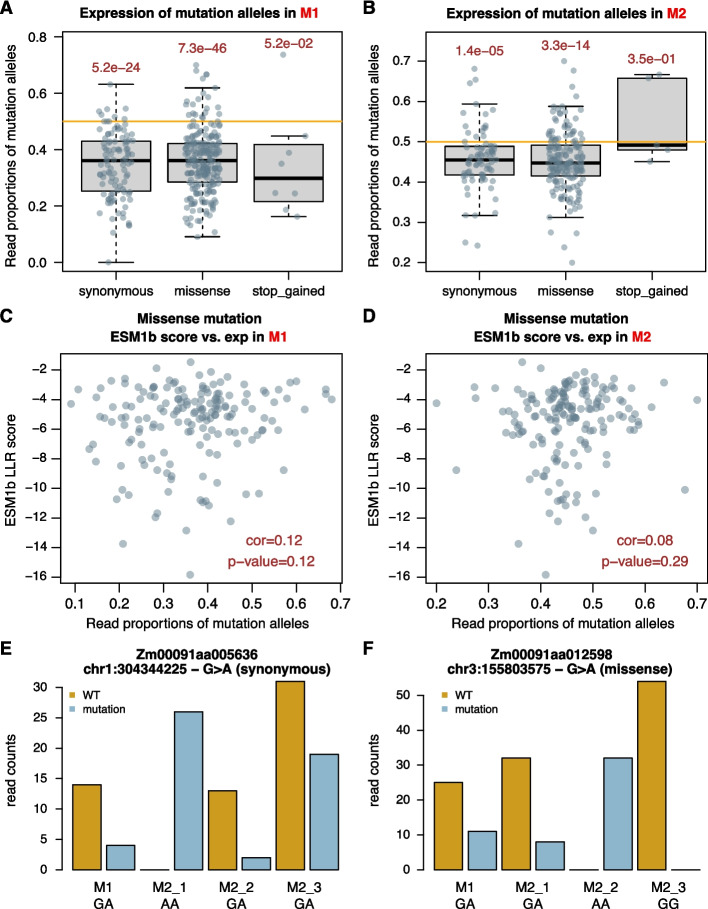

Transcriptional analysis of genic EMS alleles

To understand transcriptional expression of mutant alleles of EMS mutations on genes, RNA-seq was generated for additional 13 Chang7-2-derived EMS M1 lines, which exhibited heterozygous for each EMS mutation site. For each M1 line, three RNA-seq datasets were generated for three M2 individual plants. In total, four RNA-seq datasets were generated per M1 family. At the same time, WGS was produced for each of the 13 M1 lines for discovering EMS mutations. On average, 1,243 EMS mutations were identified from each M1 using WGS data. To find EMS mutations on expressed transcripts, EMS mutations were called independently using all the RNA-seq datasets. Only EMS mutations discovered by using both WGS and RNA-seq were further analyzed. To further avoid falsely discovered EMS mutations, we required that each EMS mutation was detected in one M1 family and only in one M1 family. As a result, 30.3% EMS mutations detected using WGS data were supported by RNA-seq reads covering transcribed genic regions. Of M1, relative expression of a mutant allele was determined by calculating the proportion of RNA-seq reads of the mutant allele to the total reads from both mutant and wildtype alleles. Of M2, for each EMS mutation, the heterozygous EMS mutation genotype was first found from three M2 individuals. If identified, relative expression of a mutant allele was determined by calculating the proportion of total RNA-seq reads of the mutant allele to the total reads from both mutant and wildtype alleles of all heterozygous M2 individuals. In both M1 and M2, the means of relative expression of EMS mutant alleles were significantly lower than 0.5 (t-tests, p-value = 1.8e-50 for M1 and p-value = 6.7e-17 for M2), indicative of lower expression of the mutant allele as compared to the wildtype allele in general. Among mutation types, the means of relative expressions of missense and synonymous mutant alleles were significantly lower than those of wildtype alleles in both M1 and M2 (Fig. 5A, B). For example, both a synonymous EMS mutation on Zm00091aa005636 and a missense EMS mutation on Zm00091aa012598 showed consistently lower expression of the mutant alleles as compared to that of wildtype alleles in both M1 and M2 heterozygous individuals (Fig. 5C, D). Zm00091aa005636 is a cnr7 homologous gene encoding a cell number regulator that could potentially affect plant and organ size [33], while Zm00091aa012598 is a poc1B homologous gene ensure centriole integrity in human cells [34]. Most relative expressions of mutant alleles due to premature stop codons were low in M1 but not in M2 (Fig. 5A, B). To examine the potential underlying mechanisms for the biased expression of missense or synonymous mutation alleles, the functional effect of each missense allele and the codon usage of synonymous alleles were examined. As a result, the relative expression of missense alleles was not associated with their effect scores as estimated by using the ESM1b model (Fig. 5E, F). Codon usages of synonymous mutations were also analyzed. As compared with wildtype alleles, codons of most synonymous mutations were less frequently used in Chang7-2 coding sequences (Additional file 1: Fig. S10). However, for synonymous mutations, we did not observe the association between the ratios (mutant:wildtype) of codon usages and relative expressions of mutation alleles in both M1 and heterozygous M2 individuals (p-values > 0.38) (Additional file 1: Fig. S10).

Fig. 5.

Expression of mutant alleles in EMS lines. A, B Proportions of RNA-seq reads from mutant alleles of total reads in M1 (A) and in heterozygous M2 (B) were used to represent the relative expression (exp) of a mutant allele, which were plotted versus mutation types. Stop_gained stands for mutations introducing premature stop codons. C, D Relative expressions of missense alleles in M1 (C) and in heterozygous M2 (D) versus variant effect scores (LLR) estimated by ESM-variants (ESM1b). cor: correlation coefficient; p-value: the p-value from a correlation test. E, F Read counts of wildtype (WT) and EMS mutation alleles of two genes in four RNA-seq datasets. Genotypes (e.g., GA) in M1 and three M2 individuals are listed below sample names. GA: heterozygous; GG: homozygous wildtype; AA: homozygous mutation

Language models facilitated identification of causal mutations underlying mutant phenotypes

Chang7-2 EMS mutants provide a valuable resource for forward genetics analyses. We analyzed an albino mutant observed in the EMS accession of ems21S398203. BSR-seq, bulked segregant RNA-seq analysis, was conducted on the EMS mutant populations to map the genomic locus underlying the albino phenotype (Fig. 6A) [35]. BSR-seq analysis using EMS mutations of ems21S398203 found that the EMS mutation site at 147,910,306 bp on chromosome 10 was strongly associated with the albino mutant phenotype (Fig. 6B, Additional file 2: Table S25). The PlantCAD LLR score of the mutation was −8.1, indicating it is a deleterious mutation. The mutation produced a glycine (G) to glutamic acid (E) change at the 989th amino acid (G989E) of Zm00091aa039132, which is homologous to a known albino gene, w2 (Fig. 6C) [36]. The ESM1b LLR score of the G989E missense mutation was −14.4, consistently evidencing its deleterious impact on the gene function. Genotyping the mutation site in Zm00091aa039132 of M2 plants showed that only homozygous mutants of the mutated allele exhibited an albino phenotype (Additional file 2: Table S26), further supporting the G989E alternation is the causal mutation and suggesting the mutation allele is recessive.

Fig. 6.

Characterization of ems21S398203 mutant. A Phenotypes of a wild type and an albino mutant (ems21S398203). B BSR-seq analysis of Ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) mutations. X-axis stands for the accumulated chromosomal position of each mutation. Y-axis stands for the probability of complete linkage of each mutation with the albino causal mutation. The size of each dot representing an EMS mutation is scaled with its PlantCAD prediction score. The red arrow points at a prioritized EMS mutation with a high linkage probability and predicted as a deleterious mutation. C The gene model of w2, and the missense mutation (G989E) of the ems21S398203 mutant in the w2 gene. The red asterisk indicates the EMS mutation site

A glossy mutant (ems21S377304) was observed in an M2 family (Additional file 1: Fig. S11A). Examination of wax accumulation on leaf surfaces via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) confirmed the reduction of cuticular wax in mutants (Additional file 1: Fig. S11A). Total leaf surface wax on ems21S377304 was reduced by 42% (Additional file 1: Fig. S11B). A missense mutation at 172,623,220 bp on chromosome 4 occurred in the previously identified glossy gene gl4 [37]. The PlantCAD LLR score of the mutation was −11.3 and the predicted ESM1b LLR score of the missense change from glutamic acid to lysine at the 152th amino acid (E152K) of Zm00091aa017103 was −12.1, strongly indicative of a deleterious impact (Additional file 1: Fig. S11C). The phenotypic co-segregation with the mutation genotype supported that the missense mutation is recessive and responsible for the mutant phenotype (Additional file 2: Table S26). Using a similar strategy, underlying EMS mutations were identified for two additional phenotypes. An EMS mutation (ems21S371203) in the splicing acceptor of y9 resulted in the phenotype of white kernels [38] (Additional file 1: Fig. S12). A nonsense mutation (ems21S399802) in ms28, a known male sterility gene, was associated with male sterility (Additional file 1: Fig. S12) [39]. Both y9 and ms28 mutations were predicted to impose deleterious impacts through PlantCAD, whose LLR scores were −10.4 and −7.6, respectively. Collectively, both large language models provide highly valuable tools for evaluating the functional impacts of mutations, facilitating the identification of causality.

Discussion

This study constructed a chromosome-level reference genome for the elite maize inbred line Chang7-2 with both protein-coding genes and transposable elements annotated. The genome assembly is near-complete as 10 chromosomes, or pseudomolecules, contain only 81 gaps. Comparisons with other diverse maize inbred lines found unique genomic variations, including a highly divergent 25 Mb inversion (INV_2). However, no lines in the 28 elite inbred lines developed in the US, A188, Mo17, and 26 NAM founders, carried the Chang7-2 haplotype of INV_2. The result indicates that Chang7-2 related varieties likely have not been introduced in early breeding programs in the US. Inbred Chang7-2 is an important genetic source developing male donors for hybrid production. Understanding the uniqueness of Chang7-2 and functional genetic elements relevant to agronomic traits is valuable for the revelation of its heterotic contribution in the future. The genome sequence and annotation produced in this study are valuable for future genetic studies of Chang7-2.

This study contributes one of the largest resources of EMS mutations for exploring genetics and genomics in maize. The collection of over 2.5 million EMS mutations of Chang7-2 will complement the current sequence-indexed maize mutant resources, such as the B73 EMS mutant stock [21], Zheng58 EMS mutants [40], and various Mutator mutant stocks [15–18]. From the breeding point of view, among published mutant stocks, the Chang7-2 EMS mutant stock is an important large-scale mutant resource for direct improvement of male donors. The EMS mutant stock along with its high-quality genome will open a door for genetic studies of agronomic traits and heterosis.

We established a WGS and bioinformatics procedure for reliable identification of EMS mutations, each of which was in the heterozygous form in M1 plants. Initially, 10x was demonstrated to achieve reasonable accuracy and power for mutation detection. Second, we developed a mutation calling pipeline through GATK4 [41]. Only EMS-type mutations, which involve G(C) to A(T) transitions were analyzed. For the final mutation set, the maximum of four EMS lines carrying the same EMS mutations were allowed, which is referred to as a population filtering. The population filtering is critical to avoid falsely discovered mutations that were derived from errors in the reference genome, misalignments, heterozygous residues, and, possibly, genomic sites vulnerable to sequence errors [42]. Although the initial in silico estimated accuracy of the mutation discovery using seven EMS lines ranged from 49 to 78% (Additional file 2: Table S13), the experimental validation of over 100 mutations obtained after the population filtering revealed that 84% of the mutations can be recovered from M2 or M3 seeds. The higher validation than the in silico estimation may attribute to the population filtering, and/or the limited EMS lines used in the validation.

We annotated EMS mutations to find EMS mutations with substantial functional impacts. As expected, only a small proportion of EMS mutations were annotated with deleterious impacts on protein functions due to sequence alterations at stop codons and splicing sites. We evaluated the impacts of large numbers of missense mutations with the ESM1b protein model, an artificial intelligence (AI) tool using a large language model [31], adding 15,264 EMS mutations, 27% of missense mutations, as potentially impactful mutations. The DNA language model PlantCAD enables the prediction of functional impacts at every EMS mutation site and the prediction does not rely on gene annotation [32]. Our validation using both Arabidopsis and maize curated missense mutation databases showed that the precisions from both ESM1b and PlantCAD predictions were very high, suggesting that deleterious missense mutations identified by either model could probably impose a high functional impact. The PlantCAD prediction indicates, unsurprisingly, that the proportion of deleterious mutations on non-coding regions or causing synonymous changes is much smaller than that of mutations causing non-synonymous mutations or affecting splicing. From our result, 0.1–1% percent of mutations in non-coding sequences or those causing synonymous changes could have deleterious impacts. They, however, are often overlooked due to the lack of assessment tools. DNA language models, such as PlantCAD, could help fill this gap by providing accurate effect estimation for these mutations. The adaptation of both protein and DNA large language models to assess functional impacts of EMS mutations represents an early demonstration of the potential of state-of-the-art AI models in genomics. Our results highlight the promise of AI-driven approaches for advancing genomic analysis and interpretation.

The density distributions of ESM1b prediction scores of the EMS missense mutations identified from our experiments and all possible EMS missense mutations in the Chang7-2 genome are nearly identical with a slightly lower proportion of experimental EMS mutations predicted with deleterious impacts. The result indicates the experimental EMS missense mutations were under a very weak selection, which is expected given all the experimental missense mutant alleles were in the heterozygous form and deleterious dominant mutations are probably rare. In contrast, missense mutations predicted to possess deleterious impacts were largely purified in diverse maize inbred lines. The result indicates that massive novel functional variations are present in the Chang7-2 EMS mutant stock, providing valuable resources for genetics studies and breeding.

Transcription analysis in M1 and M2 leaf samples showed that, overall, mutant alleles on transcribed regions expressed at a lower level as compared to corresponding wildtype alleles. We should note that some WGS-informed genic EMS mutations that were not supported by RNA-seq may be due to complete silence of the mutant alleles. We did not examine this group of EMS mutations because these EMS mutations cannot be clearly distinguished from the EMS mutations falsely discovered by using WGS. It was well known that nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) could reduce mRNA with a premature stop codon caused by a nonsense mutation [43]. However, we did not detect significant reduction in the transcript accumulation of nonsense mutation alleles in both M1 and M2. In M1, the relative expressions of most nonsense mutation alleles were lower than 0.4, which was derived from the expected value of 0.5 in M1. The failure to detect a significant impact of nonsense mutation alleles may be attributed to the small number of total nonsense mutations with a few outliers. For unknown reasons, relative expressions of most nonsense mutations in heterozygous M2 plants were close to 0.5.

The finding of reduced transcripts of mutation alleles was consistent across two major mutant types, namely, missense and synonymous mutations. Our analysis showed that the functional impacts of missense mutations estimated by using homologous protein sequences across kingdoms were not significantly associated with transcript accumulation. Synonymous mutations are generally considered to impose neutral functional impacts due to no alteration in protein sequences [44]. Synonymous mutations were found to frequently disturb gene expression and affect fitness in yeast, indicative of non-neutral impacts [45]. A recent study showed a synonymous substitution on a gene encoding an aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase caused changes in m6A modification on surrounding adenosine residues and the RNA structural conformation [46]. Here, we observed that some synonymous mutant alleles exhibited reduced accumulation of mRNA transcripts. Codon analysis showed that a high proportion of synonymous mutations introduce codons that are less frequently used. However, codon usages appear to not be the major reason for the reduction of the transcript accumulation of synonymous alleles. In the future, further examination of epitranscriptional modifications and mRNA structural conformation might provide additional clues. Nevertheless, our result supports that synonymous mutations are not necessarily silent changes. The observation is important for the genetics community and breeding applications that synonymous mutants should not be completely ignored.

Conclusions

In this study, the chromosome-level Chang7-2 genome was assembled and annotated, and comparisons with other maize genomes showed that Chang7-2 carries unique sequences that are not commonly present in other maize lines. More than 2.5 million mutations in Chang7-2 were generated through EMS mutagenesis, of which over 15 thousand mutations were annotated to be deleterious with the aid of large protein and DNA language models. The effective annotation of deleterious mutations accelerated the discovery of four causal mutations responsible for various traits.

Methods

Chang7-2 reference genome assembly

Genomic DNA of Chang7-2 was extracted from the third leaves of four-leaf plants using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (QIAGEN). Genomic DNA was sheared using g-Tubes (Covaris) and purified with AMPure PB magnetic beads. SMRT bell libraries were constructed using the Pacific Biosciences SMRT bell template prep kit 1.0. The constructed library was size-selected by Sage ELF for molecules 14–17 kb, followed by primer annealing and the binding of SMRT bell templates to polymerases with the DNA Polymerase Binding Kit. Sequencing was carried out on a Pacific Bioscience Sequel II platform at Annoroad Gene Technology company. Software Hifiasm (0.16.1-r375) was used for the de novo assembly with the parameters of “-l0 -n5” [22].

Prior to scaffolding, contigs from mitochondria and chloroplasts were identified based on the homology with the mitochondrion and chloroplast reference genomes and differential coverages of Illumina short reads from leaf and immature embryo tissues. The proportion of mitochondrial DNAs are expected to be more in immature embryos and the proportion of chloroplast DNAs are expected to be more in leaves [7]. Therefore, we categorized contigs to potential mitochondrial sequences (pmt) if aligned reads per kilobase of contig sequences per million total reads (RPKM) of immature embryos is 1.5 times of that of leaves. In contrast, if the contig RPKM value of leaves was five times that of immature embryos, the contig was categorized to a potential chloroplast sequence (ppt).

For scaffolding, HiC libraries were generated and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq, producing 2 × 150 bp reads [47]. The software 3d-dna (version:180922) was used with HiC data for scaffolding the contigs that were not categorized to either pmt or ppt [24]. The parameters of “-r 0 -q 10” were specified for “run-asm-pipeline.sh”. The 3d-dna scaffolding result was manually examined in Juicebox (version 1.11.08) for corrections [23]. Scaffolds and contigs with a length less than 25 kb were discarded. The remaining sequences were then merged with pmt and ppt sequences with at least 25 kb, resulting in the Chang7-2 reference genome version 1 (Chang7-2v1).

Genome annotation

The transposable element (TE) annotator EDTA (v2.0.0) was used to annotate TEs and other repetitive sequences [48].

We referred to an updated gene annotation process used for annotating NAM genomes [8, 49]. RNA-seq from ten tissues of Chang7-2 were produced to provide evidence for gene annotation. Ten tissue types include root, seedling, the base, middle, and tip of leaves, tassel, ear, anther, endosperm, and embryo (Additional file 2: Table S4). RNA-seq were mapped to Chang7-2v1 using STAR (2.7.9a) [50]. STAR alignments were used for the identification of splicing junctions using Portcullis (v1.2.4) [51], and for transcript assembly using multiple programs, namely, Cufflinks (v2.2.1) [52], Stringtie (v2.0) [53], Class2 (v2.1.7) [54], and Strawberry (v1.0.2) [55]. The resulting assembled transcripts were collapsed, selected, and improved using Mikado (v2.3.3) [56] with the additional inputs of splicing junctions using Portcullis (v1.2.4) [51], open reading frames (ORFs) using TransDecoder (v5.5.0) [57], and homology in the Viridiplantae SWISS-Prot database (https://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/33090) identified using BLASTX (v2.12.0) [58]. TEs of Mikado gene models were removed using TESorter with the parameter of –filtpara “-cov 80 -eval 1e-6” (v1.3) [59].

In addition to the gene prediction from Mikado, two more gene annotation datasets were generated. First, GeMoMa (v1.8) was used to project gene models of five NAM founders, namely B73, P39, Tx303, M37W, and NC350 on Chang7-2v1 [60]. All five predicted transcripts were merged using GeMoMa. Second, BRAKER2 (v2.1.6) was used for gene annotation with RNA-seq evidence from STAR alignments and protein evidence from the Mikado output [61]. Three gene annotation datasets were merged using GeMoMa with the weight of 1.2 for the GeMoMa gene annotation, 1.1 for the Mikado gene annotation, and 0.2 for the BRAKER2 gene annotation. The merged gene annotation was input to Maker (v2.31.10) to assess evidence supports for gene prediction, which was quantified using the Annotation Edit Distance (AED) score [62]. The Maker annotation using the repeat-masked genome generated with Repeatmasker (4.0.7) (http://www.repeatmasker.org). Predicted transcripts with AED smaller than 0.75 remained. TESorter was then implemented to filter TE genes, resulting in the final gene annotation of Chang7-2 (Chang7-2v1a).

Functional annotation was conducted through InterProScan (v5.55–88.0) and BLASTP to all proteins to the SWISS-Prot database (www.uniprot.org) with the e-value cutoff of 1e − 6.

Syntenic genes between Chang7-2 and B73

Synima was used to identify syntenic gene pairs between Chang7-2 and B73 [63]. In brief, the reference genome, genome annotation, the coding DNA sequences and the protein sequences of both Chang7-2 and B73 were input to identify orthologous and paralogous gene clusters between Chang7-2 and B73 by the “Orthofinder” method in Synima [64]. Genes in a cluster and within 10 Mb in distance between gene positions in the two genomes were deemed as syntenic gene pairs by the “DAGchainer” package in Synima [65].

Identification of CG methylation using HiFi reads

PacBio HiFi sequencing data were used to identify 5-methylcytosine (5mC) modification, cytosine methylation, at CG sites, including four steps (https://github.com/PacificBiosciences): 1) Raw subreads were merged to consensus reads with HiFi kinetics annotation by the package “pbccs” of PacBio tools. 2) A model implemented in the primrose software was used to predict 5mC probabilities from HiFi reads and the SAM tags encoding 5mC positions and methylation scores were added to all HiFi reads. 3) HiFi reads with 5mC tags (supplied in an unaligned BAM format) were aligned to the reference genome using pbmm2. (4) From alignments, pileup scores for 5mC across CG sites were obtained using PacBio’s CG tools. The Modification Probabilities (MP) of each nucleotide site represents the possibility of the site to be methylated. According to the ratio of sites under different MPs, nucleotide sites with MPs less than 10% were considered as unmethylated sites and nucleotide sites with MPs larger than 80% were considered as methylated sites.

Detection of synteny and structural variation between maize genomes

The Syri pipeline using Nucmer as the aligner was employed for analyzing structural variation with 28 diverse maize inbred lines [26, 27]. The genome sequences of the 28 inbred lines include the reference genome B73 (B73-5.0), A188v1, telomere-to-telomere Mo17 assembly (Mo17CAU2), and the first version of assemblies of the other 25 NAM founders [5, 7, 8]. Syntenic regions, highly divergent regions, inversions, and other structural variations were parsed from Syri outputs.

Conversion of physical coordinates between different versions of B73 reference genomes

Genomic locations on B73v2 of a large recombination suppression region in chromosome 1 and QTLs identified from a previous study [29] were converted to locations on B73v5 through a web tool: https://plants.ensembl.org/Zea_mays/Tools/AssemblyConverter?db=core.

EMS mutagenesis of Chang7-2

The Chang7-2 pollen was treated with the 0.07% solution of EMS (M0880, Sigma-Aldrich) in paraffin oil (M18512; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min prior to the application to silks of Chang7-2 ears for pollination, producing M1 seeds [66]. M1 plants grown from M1 seeds were then self-pollinated to generate M2 seeds. Similarly, M2 plants were selfed for M3 seeds.

Mutation validation

EMS mutations were chosen for the validation. Primers were designed to produce fragments of 400–1000 bp containing mutation sites (Additional file 2: Table S16). Genomic DNA was extracted from M2 or M3 seedlings derived from M1 plants containing mutations. PCR products were Sanger sequenced and compared with the wildtype Chang7-2.

Scanning electron microscope of epicuticular wax

Glossy mutants ems21S377304 and wild types were grown in the greenhouse (28 °C) under 16/8 h light/dark. The second leaves collected from mutant and wild types were used for scanning electron microscopy (SEM; SU8010, Hitachi, Japan) analysis [67]. In brief, samples were cut into a small square and immediately put into 1% osmium acid fixative solution for 48 h. Leaves were dehydrated and dried, and then analyzed with a SEM.

Pilot analysis to optimize the sequencing depth for mutant detection

To optimize the depth of WGS for detecting EMS mutations, we generated a high-depth sequencing data (> 25x) for each of seven EMS M1 lines. An in-house Perl script “vcfbox” (github.com/liu3zhenlab/vcfbox) was used to filter variants discovered by GATK to identify the ground truth mutations from seven EMS mutants [41]. Briefly, five reads for each of the reference and mutant alleles are required for a mutation site. Each mutation must be G to A or C to T changes and only occurs in one EMS mutant. Further, WGS sequencing Illumina data of wildtype Chang7-2 mentioned above were used to ensure that the mutation sites showed the reference allele types in wildtype Chang7-2.

Raw reads were then randomly downsampled to various sequencing depths, ranging from 5x to 15x, with seqtk (https://github.com/lh3/seqtk), for examining the accuracy of mutation detection at each sequencing depth. The 10x depth balancing the power of mutation detection and the sequencing cost was selected for sequencing all other M1 lines.

Identification of EMS mutations in Chang7-2 M1 lines

First, adaptor and low-quality sequences of reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic (version 0.38) with the parameters of “ILLUMINACLIP: < adaptor > :3:20:10:1:true LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:13 MINLEN:50” [68]. Trimmed reads were aligned to Chang7-2v1 with BWA [69]. Second, GATK4 was used to identify variants between each Chang7-2 M1 line and Chang7-2v1 [41]. Prior to variant calling, the GATK module “MarkDuplicates” was used to mark duplicated reads. Then the GATK module “HaplotypeCaller” was used to identify raw variants. Third, to identify EMS mutations, additional filtering was implemented: 1) Only bi-allelic variant sites with at least three supporting reads were retained. 2) Perl script “vcfbox.pl” (github.com/liu3zhenlab/vcfbox.git) was used to find sites with sufficient read support for the mutant/wildtype alleles with the parameters “-A 5 -a 0.9 -R 1 -r 0.1 -N 3 -n 0.2”. 3) Only variant sites with the mutation from G to A or C to T were considered as candidate EMS mutations. 4) Across all EMS lines, candidate EMS mutations that existed in more than four M1 lines were removed.

Filtering Chang7-2 M1 lines that were sequenced

We removed M1 lines with too high (> 10,000) or too low (< 500) EMS mutations found, or an unexpected rate of mutations from A to G or T to C (i.e., > 0.4 of the ratio between these mutations and mutations of all types). As a result, of 1802 EMS M1 lines with WGS data, four lines containing at least 0.25 million mutations were considered to be contaminated lines and thus were removed. Eighty-two EMS lines containing no more than 500 mutations were also removed as the falsely discovered mutations may be high in these 82 mutants.

Evaluation of functional impacts of EMS mutations with SNPEff

The SNPEff software (5.0e) was used to annotate EMS mutations [30]. The impacts of mutations were grouped to four categories: high, moderate, low, and modifier (http://pcingola.github.io/SnpEff/se_inputoutput/).

Predicting impacts of missense EMS mutations with the protein language model ESM1b

Impacts of missense mutations identified from SNPEff were further assessed with ESM-variants [31]. The ESM1b model (ESM1b model: esm1b_t33_650M_UR50S) was used (github.com/ntranoslab/esm-variants). The model performance was evaluated by analyzing the curated Arabidopsis curated data containing 2,910 missense mutations causing detectable mutant phenotypes and 1,583 non-deleterious missense mutations [70]. Based on the evaluation result, missense EMS mutations with ESM1b LLR scores smaller than −7.5 were categorized as deleterious missense mutations.

Predicting impacts of EMS mutations with the DNA language model PlantCAD

Zero-shot scores, also referred to as PlantCAD LLR scores, were estimated using the model PlantCaduceus_l32 to represent the functional impacts of all EMS mutations [32]. The Arabidopsis curated data containing 2,910 missense mutations were first used to assess the model performance [70]. Since only protein sequences and amino acid changes were available in curated data, we mapped proteins to the TAIR10 reference genome with miniprot and converted amino acid changes to all possible DNA changes [71, 72]. The correlation of PlantCAD LLR scores between duplicated DNA changes for the same amino acid changes was 0.91 (Additional file 1: Fig. S13). We therefore used their average score to represent the effect of each missense mutation. In the final DNA mutation set, 1,872 deleterious mutations and 1,509 non-deleterious mutations were examined using both ESM1b and PlantCAD. Based on the assessment of the effect prediction of missense mutations, EMS mutations with PlantCAD LLR scores smaller than −6 were categorized to the group with deleterious impacts.

Evaluation of LLR thresholds for deleterious mutations using maize missense mutations causing visible mutant phenotypes

Missense mutations (N = 54) on 35 genes causing visible phenotypes in maize plants were collected. These missense mutations represent a small set of deleterious maize mutations, referred to the Maize Missense Mutation Database (3MD) v0.3 (Additional file 2: Table S22). The effects of these missense mutations were predicted using both ESM1b and PlantCAD. Similar to the Arabidopsis missense mutation collection, changes in protein sequences were curated. We therefore employed a similar strategy to map proteins to the B73v5 reference genome with miniprot and convert amino acid changes to all possible DNA changes. As a result, 49 mutations were confidently mapped and seven had two types of DNA alternations per amino acid mutations. The PlantCAD LLR scores between duplicated DNA changes for the same amino acid changes were also similar. We therefore used their average PlantCAD LLR score to represent the effect of each missense mutation.

We extracted missense SNPs in the syntenic regions between Chang7-2 and at least two genomes from the NAM founders, A188, and Mo17. The functional effects of these missense SNPs were deemed to be non-deleterious, although a very small proportion might impose some levels of deleterious impacts. We applied ESM1b to estimate their functional effects. Fifty-four missense SNPs were randomly extracted to pair with the 3MD (v0.3) for the assessment of ESM1b and PlantCAD models.

Allelic transcription analysis of 13 M1 plants

Both WGS and RNA-seq data of leaf samples of 13 Chang7-2 EMS M1 plants were conducted. WGS was first used to identify EMS mutations with the method for the EMS mutation discovery described. For each of 13 M1 families, three M2 individuals were subjected to RNA-seq. In total, four RNA-seq datasets per family were produced, including one M1 sample and three M2 samples. Variants were then called using RNA-seq data as the method employed for BSR-seq. Overlapping variants identified by using both WGS and RNA-seq were quantified for expression of mutation alleles. To avoid falsely discovered mutations, for each mutation, at least one individual sample identified as a heterozygote or a homozygote of the mutation allele in four RNA-seq samples of a family. We therefore only examined EMS mutation sites where mutation alleles were transcribed in at least one RNA-seq sample. Note that some EMS mutations in transcribed regions in genes might not be included due to undetectable expression of the mutant allele.

For allelic expression analysis, the proportion of the mutation allele out of total reads summed from both wildtype and mutation alleles was used to represent the relative expression of a mutation allele. In M1, only the mutation sites with the total reads larger than 18 were analyzed. In M2, for each mutation site, heterozygous individuals were identified when both wildtype and mutation alleles had more than one read and read counts of each allele were higher than 5% of the total reads from both alleles. Expression of mutation alleles were only examined for heterozygous M2 individuals. SNPEff was employed to evaluate the impacts of all mutation sites examined [30]. T-tests were conducted to test the null hypothesis that the mean of relative expressions of mutation alleles is no difference from 0.5. For missense mutations, ESM1b was employed for assessing their functional impacts [31].

Codon usage analysis

Usages of codons were determined for Chang7-2 using the coding sequences of the annotation of Chang7-2v1a. The codon usage analysis determined the occurrence of each codon in coding sequences. We then determined the codon change caused by a synonymous mutation from 13 families that were subjected to RNA-seq. For each synonymous mutation, the codon occurrences of the wildtype and mutation alleles in Chang7-2 coding sequences can be determined, and then their ratio (mutation:wildtype) was calculated. The codon usage ratios of synonymous mutations were examined for their relationship with relative expressions of mutation alleles in both M1 and M2 through fitting a linear model.

Bulked segregant RNA-seq (BSR-seq) analysis of Chang7-2 EMS mutants

The M2 segregation population of an albino mutant (ems21S398203) was used for BSR-seq [35]. Raw RNA-seq reads were trimmed by Trimmomatic with the same parameters as used in EMS variant calling. Trimmed reads were aligned to Chang7-2v1 by STAR [50] with the parameters “–alignIntronMax 100000 –alignMatesGapMax 100000 –outSAMattrIHstart 0 –outSAMmultNmax 1 –outSAMstrandField intronMotif –outFilterIntronMotifs RemoveNoncanonicalUnannotated –outFilterMismatchNmax 5 –outFilterMismatchNoverLmax 0.05 –outFilterMatchNmin 50 –outSJfilterReads Unique –outFilterMultimapNmax 1 –outSAMmapqUnique 60 –outFilterMultimapScoreRange 2”. The variants were called by GATK4 HaplotypeCaller function through an RNA-seq short variant calling pipeline [41]. The bi-allelic SNPs that passed the standard GATK hard-filtering cutoff (FS > 60, ReadPosRankSum < −8.0, QUAL < 30.0, SOR > 3.0, MQ < 40.0, MQRankSum < −12.5) were retained for BSR-seq analysis. BSR-seq statistical analysis was described previously. The probability of complete linkage between a marker and the potential causal variant larger than 0.3 were considered as a significant marker associated with the phenotype.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Length distribution of PacBio HiFi reads. Fig. S2. HiC contact heatmap and scaffolding of the genome assembly. Fig. S3. CG methylation within and around genes. Fig. S4. SNP density of syntenic blocks. Fig. S5. Recombination rates per megabase on chromosome 1. Fig. S6. Phenotypes of M2 mutants. Fig. S7. Density of cytosine methylation percentages at CG sites. Fig. S8. Boxplots of lengths genes with multiple EMS mutations. Fig. S9. Comparison of predictions with PlantCAD versus ESM1b. Fig. S10. Allelic expression and codon usage of synonymous mutations. Fig. S11. Characterization of ems21S377304 mutant. Fig. S12. Characterization of ems21S371203 and ems21S399802 mutants. Fig. S13. PlantCAD scores of two DNA mutations of the same missense mutations.

Additional file 2: Table S1. Statistics of assembled contigs prior to scaffolding. Table S2. Lengths of assembled chromosomes. Table S3. Summary of repeat contents from EDTA. Table S4. Tissues used for RNA-seq. Table S5. Summary of isoform counts per gene. Table S6. Synteny of 10 chromosomes between Chang7-2 and other maize lines. Table S7. The top 15 largest syntenic blocks between Chang7-2 and other maize inbred lines. Table S8. Counts of genes mutually uniquely syntenic with Chang7-2 genes. Table S9. Summary of structural variations between Chang7-2 and other inbreds. Table S10. List of large inversions between Chang7-2 and other inbreds. Table S11. Summary of repeat contents of INV_2 regions. Table S12. Summary of visible mutant phenotypes observed in the M2 population. Table S13. Mutation detection power and accuracy using downsampled data. Table S14. Summary of WGS 2 × 150 reads and mutations of EMS lines. Table S15. Counts of EMS mutations in different genome regions. Table S16. PCR validation of selected EMS mutations. Table S17. Validation of EMS mutations. Table S18. Summary of the SNPEff evaluation of EMS mutations. Table S19. Evaluation of variant prediction AI models using curated Arabidopsis data. Table S20. Prediction results of curated Arabidopsis missense mutations using ESM1b and PlantCAD. Table S21. Classification of deleterious mutants determined by PlantCAD prediction. Table S22. A collection of missense mutations causing visible plant phenotypes in maize. Table S23. Prediction results of curated maize missense mutations using ESM1b and PlantCAD. Table S24. Evaluation of variant prediction AI models using curated maize data. Table S25. Linkage probabilities of EMS mutations with the causal gene through BSR-seq analysis. Table S26. The phenotype of mutants with different genotypes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Matthew Hufford and Arun Seetharam at Iowa State University for sharing information related to genome annotation, Li Lei at the DOE Joint Genome Institute for providing guidance on accessing Arabidopsis variant annotation data. Data analysis was supported by the high-performance computing platform of Bioinformatics Center, Nanjing Agricultural University.

Peer review information

Mingqiu Dai and Wenjing She were the primary editors of this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team. The peer-review history is available in the online version of this article.

Authors’ contributions

J.Z., S.L., H.W., M.G., X.Z., and J.F. conceived and designed experiments. Y.W., Q.W., R.L., and Y.Q. performed the EMS mutagenesis and collected data. C.H., Y.W., Q.W., J.Y., F.F.W., J.Z., and S.L. assembled the genome and analyzed data. J.Z., Y.W., Q.W., R.L., Y.Q., Q.H., H.L., and X.L. managed the mutant collection. Y.W., C.H., Q.W., F.F.W., J.Z., and S.L. wrote the manuscript with comments from other authors. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

We thank the funding provided by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1200500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U24A20384), the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of CAAS (CAAS-CSCB-202403), the DOE awards (DE-SC0023138 and DE-SC0026031), the USDA NIFA awards (2021-67013-35724), and the NSF awards (2311738 and 2011500). This is contribution no. 24-234-J from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station, Manhattan, Kansas.

Data availability

The Chang7-2 genome assembly was deposited at NCBI (JBFRYI000000000) [73]. Both the genome assembly (Chang7-2v1) and the annotation (Chang7-2v1a) were deposited to [MaizeGDB.org](http:/maizegdb.org) [74]. Raw PacBio whole-genome sequencing data, Illumina whole-genome sequencing data, Illumina RNA-Seq data are available at Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the project of PRJNA1117575 [75]. Scripts related to the manuscript are available on GitHub at https://github.com/PlantG3/Chang7-2v1.git [76]. The release version (v1.0.0) of the GitHub repository has been published in Zenodo [77]. All scripts are distributed under the MIT license. The mutant datasets generated in this study are available publicly [78]. The curated *Arabidopsis* missense dataset was downloaded from Table S2 in Kono et al. [70, 79].

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SL is the co-founder of Data2Bio, LLC. Other authors claim no competing interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Yiru Wang, Cheng He and Qiqi Wang contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Sanzhen Liu, Email: liu3zhen@ksu.edu.

Jun Zheng, Email: zhengjun02@caas.cn.

References

- 1.Springer NM, Ying K, Fu Y, Ji T, Yeh C-T, Jia Y, et al. Maize inbreds exhibit high levels of copy number variation (CNV) and presence/absence variation (PAV) in genome content. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenaillon MI, Sawkins MC, Long AD, Gaut RL, Doebley JF, Gaut BS. Patterns of DNA sequence polymorphism along chromosome 1 of maize (Zea mays ssp. mays L.). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9161–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walbot V. Genomic, chromosomal and allelic assessment of the amazing diversity of maize. Genome Biol. 2004;5:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Q, Dooner HK. Remarkable variation in maize genome structure inferred from haplotype diversity at the bz locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17644–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Wang Z, Tan K, Huang W, Shi J, Li T, et al. A complete telomere-to-telomere assembly of the maize genome. Nat Genet. 2023;55:1221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Y, Colantonio V, Müller BSF, Leach KA, Nanni A, Finegan C, et al. Genome assembly and population genomic analysis provide insights into the evolution of modern sweet corn. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin G, He C, Zheng J, Koo D-H, Le H, Zheng H, et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of a regenerable maize inbred line A188. Genome Biol. 2021;22:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hufford MB, Seetharam AS, Woodhouse MR, Chougule KM, Ou S, Liu J, et al. De novo assembly, annotation, and comparative analysis of 26 diverse maize genomes. Science. 2021;373:655–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nie S, Wang B, Ding H, Lin H, Zhang L, Li Q, et al. Genome assembly of the Chinese maize elite inbred line RP125 and its EMS mutant collection provide new resources for maize genetics research and crop improvement. Plant J. 2021;108:40–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnable PS, Ware D, Fulton RS, Stein JC, Wei F, Pasternak S, et al. The B73 maize genome: complexity, diversity, and dynamics. Science. 2009;326:1112–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang N, Liu J, Gao Q, Gui S, Chen L, Yang L, et al. Genome assembly of a tropical maize inbred line provides insights into structural variation and crop improvement. Nat Genet. 2019;51:1052–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang B, Hou M, Shi J, Ku L, Song W, Li C, et al. De novo genome assembly and analyses of 12 founder inbred lines provide insights into maize heterosis. Nat Genet. 2023;55:312–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lai J, Li R, Xu X, Jin W, Xu M, Zhao H, et al. Genome-wide patterns of genetic variation among elite maize inbred lines. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1027–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang R, Xu G, Li J, Yan J, Li H, Yang X. Patterns of genomic variation in Chinese maize inbred lines and implications for genetic improvement. Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131:1207–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Settles AM, Holding DR, Tan BC, Latshaw SP, Liu J, Suzuki M, et al. Sequence-indexed mutations in maize using the UniformMu transposon-tagging population. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcon C, Altrogge L, Win YN, Stöcker T, Gardiner JM, Portwood JL 2nd, et al. Bonnmu: a sequence-indexed resource of transposon-induced maize mutations for functional genomics studies. Plant Physiol. 2020;184(2):620–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang L, Zhou L, Tang Y, Li N, Song T, Shao W, et al. A sequence-indexed mutator insertional library for maize functional genomics study. Plant Physiol. 2019;181:1404–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang L, Wang Y, Han Y, Chen Y, Li M, Wu Y, et al. <article-title update="added">Expansion and improvement of ChinaMu by MuT‐seq and chromosome‐level assembly of the Mu ‐starter genome. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024;66:645–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Yeh C-T, Ji T, Ying K, Wu H, Tang HM, et al. Mu transposon insertion sites and meiotic recombination events co-localize with epigenetic marks for open chromatin across the maize genome. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarty DR, Settles AM, Suzuki M, Tan BC, Latshaw S, Porch T, et al. Steady-state transposon mutagenesis in inbred maize. Plant J. 2005;44:52–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu X, Liu J, Ren W, Yang Q, Chai Z, Chen R, et al. Gene-indexed mutations in maize. Mol Plant. 2018;11:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng H, Concepcion GT, Feng X, Zhang H, Li H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat Methods. 2021;18:170–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durand NC, Robinson JT, Shamim MS, Machol I, Mesirov JP, Lander ES, et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 2016;3:99–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dudchenko O, Batra SS, Omer AD, Nyquist SK, Hoeger M, Durand NC, et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science. 2017;356:92–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marçais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, Zimin A. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput Biol. 2018;14:e1005944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goel M, Sun H, Jiao WB, Schneeberger K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 2019;20:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan DT. A cytogenetic study of inversions in Zea mays. Genetics. 1950;35:153–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang B, Liu H, Liu Z, Dong X, Guo J, Li W, et al. Identification of minor effect QTLs for plant architecture related traits using super high density genotyping and large recombinant inbred population in maize (Zea mays). BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brandes N, Goldman G, Wang CH, Ye CJ, Ntranos V. Genome-wide prediction of disease variant effects with a deep protein language model. Nat Genet. 2023;55:1512–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhai J, Gokaslan A, Schiff Y, Berthel A, Liu Z-Y, Lai W-Y, et al. Cross-species modeling of plant genomes at single-nucleotide resolution using a pretrained DNA language model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2025;122:e2421738122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo M, Rupe MA, Dieter JA, Zou J, Spielbauer D, Duncan KE, et al. Cell number regulator1 affects plant and organ size in maize: implications for crop yield enhancement and heterosis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1057–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Venoux M, Tait X, Hames RS, Straatman KR, Woodland HR, Fry AM. Poc1A and Poc1B act together in human cells to ensure centriole integrity. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:163–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, Yeh C-T, Tang HM, Nettleton D, Schnable PS. Gene mapping via bulked segregant RNA-Seq (BSR-seq). PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Udy DB, Belcher S, Williams-Carrier R, Gualberto JM, Barkan A. Effects of reduced chloroplast gene copy number on chloroplast gene expression in maize. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:1420–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu S, Dietrich CR, Schnable PS. DLA-based strategies for cloning insertion mutants: cloning the gl4 locus of maize using Mu transposon tagged alleles. Genetics. 2009;183:1215–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li F, Murillo C, Wurtzel ET. Maize Y9 encodes a product essential for 15-cis-zeta-carotene isomerization. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:1181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Huang Y, Pan L, Zhao Y, Huang W, Jin W. Male sterile 28 encodes an ARGONAUTE family protein essential for male fertility in maize. Chromosome Res. 2021;29:189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chong L, Su H, Liu Y, Zheng L, Tao L, Bie H, et al. Creating a gene-indexed EMS mutation library of Zheng58 for improving maize genetics research. Theor Appl Genet. 2025;138:83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu F, Romay MC, Glaubitz JC, Bradbury PJ, Elshire RJ, Wang T, et al. High-resolution genetic mapping of maize pan-genome sequence anchors. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brogna S, Wen J. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) mechanisms. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:107–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King JL, Jukes TH. Non-Darwinian evolution. Science. 1969;164:788–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shen X, Song S, Li C, Zhang J. Synonymous mutations in representative yeast genes are mostly strongly non-neutral. Nature. 2022;606:725–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xin T, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Li X, Wang S, Wang G, et al. Recessive epistasis of a synonymous mutation confers cucumber domestication through epitranscriptomic regulation. Cell. 2025. 10.1016/j.cell.2025.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belton JM, McCord RP, Gibcus JH, Naumova N, Zhan Y, Dekker J. Hi-C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods. 2012;58:268–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ou S, Su W, Liao Y, Chougule K, Agda JRA, Hellinga AJ, et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 2019;20:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Phillips AR, Seetharam AS, AuBuchon-Elder T, Buckler ES, Gillespie LJ, Hufford MB, et al. A happy accident: a novel turfgrass reference genome. bioRxiv. 2022. p. 2022.03.08.483531. Available from: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2022/03/09/2022.03.08.483531. Cited 2022 Dec 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mapleson D, Venturini L, Kaithakottil G, Swarbreck D. Efficient and accurate detection of splice junctions from RNA-seq with Portcullis. Gigascience. 2018. 10.1093/gigascience/giy131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pertea M, Kim D, Pertea GM, Leek JT, Salzberg SL. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1650–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Song L, Sabunciyan S, Florea L. CLASS2: accurate and efficient splice variant annotation from RNA-seq reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu R, Dickerson J. Strawberry: fast and accurate genome-guided transcript reconstruction and quantification from RNA-Seq. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13:e1005851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venturini L, Caim S, Kaithakottil GG, Mapleson DL, Swarbreck D. Leveraging multiple transcriptome assembly methods for improved gene structure annotation. Gigascience. 2018;7. 10.1093/gigascience/giy093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Blood PD, Bowden J, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1494–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang RG, Li GY, Wang XL, Dainat J, Wang ZX, Ou S, et al. TEsorter: an accurate and fast method to classify LTR-retrotransposons in plant genomes. Hortic Res. 2022. 10.1093/hr/uhac017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Keilwagen J, Hartung F, Grau J. GeMoMa: homology-based gene prediction utilizing intron position conservation and RNA-seq data. Methods Mol Biol. 2019:161–77. 10.1007/978-1-4939-9173-0_9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Brůna T, Hoff KJ, Lomsadze A, Stanke M, Borodovsky M. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genomics Bioinform. 2021;3:lqaa108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holt C, Yandell M. MAKER2: an annotation pipeline and genome-database management tool for second-generation genome projects. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Farrer RA. Synima: a synteny imaging tool for annotated genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18:507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emms DM, Kelly S. Orthofinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Wortman JR, Salzberg SL. DAGchainer: a tool for mining segmental genome duplications and synteny. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3643–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neuffer MG, Coe J EH. Paraffin oil technique for treating mature corn pollen with chemical mutagens. 1978. Available from: https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.5555/19781667515.

- 67.Aharoni A, Dixit S, Jetter R, Thoenes E, van Arkel G, Pereira A. The SHINE clade of AP2 domain transcription factors activates wax biosynthesis, alters cuticle properties, and confers drought tolerance when overexpressed in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2463–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kono TJY, Lei L, Shih C-H, Hoffman PJ, Morrell PL, Fay JC. Comparative genomics approaches accurately predict deleterious variants in plants. G3 Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2018;8:3321–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lamesch P, Berardini TZ, Li D, Swarbreck D, Wilks C, Sasidharan R, et al. The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR): improved gene annotation and new tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D1202–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li H. Protein-to-genome alignment with miniprot. Bioinformatics. 2023;39:btad014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/JBFRYI000000000.1.

- 74.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. https://www.maizegdb.org/genome/assembly/Zm-Chang7_2-REFERENCE-CAAS-1.0.

- 75.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/?term=PRJNA1117575.

- 76.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. https://github.com/PlantG3/Chang7-2v1.git.

- 77.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. 10.5281/zenodo.17573167.

- 78.Wang Y, He C, Wang Q, Li R, Qin Y, Wang H, et al. Large DNA and protein language models enhance discovery of deleterious mutations in maize. 2025. https://maizedb.rmbreeding.cn.

- 79.Kono TJY, Lei L, Shih CH, Hoffman PJ, Morrell PL, Fay JC. Comparative genomics approaches accurately predict deleterious variants in plants. 2025. https://figshare.com/ndownloader/articles/6998387/versions/1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials