Abstract

Parallel in vitro tests, assessing the inhibition of schizont maturation, were conducted with 31 fresh isolates of Plasmodium falciparum from Thailand, using artemisinin, doxycycline, and combinations of both. The activities of artemisinin and doxycycline are obviously not correlated. Both compounds showed consistent synergism at 50% effective concentration (EC50), EC90, and EC99 levels.

With a yearly incidence of 300 million to 500 million cases and an annual number of 1.1 million to 2.7 million deaths, malaria is one of the world’s most important communicable diseases (21). Plasmodium falciparum is the cause of the most dangerous forms of malaria and is responsible for 90% of all infections worldwide. This parasite has acquired resistance to chloroquine in the large majority of areas to which it is endemic. Resistance to antifolates is widespread in South America and large parts of Southeast Asia and is rising in tropical Africa (14). Multiresistance, i.e., resistance to antimalarial agents of three or more distinct chemical groups, occurs in Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand (4, 6, 12; E. F. Boudreau, H. K. Webster, K. Pavanand, and L. Thosingha, Letter, Lancet 2:1335, 1982) and necessitates the use of artemisinin derivatives in association with other antimalarials in order to achieve effective cures (20).

Much of the problem of resistance is due to the use of drugs with a long half-life in areas with intensive malaria transmission (14, 16). In such areas it would be advantageous to use drugs with a short half-life, such as doxycycline and artemisinin or its derivatives. Although rapid in achieving clinical relief, monotherapy with artemisinin is associated with a high recrudescence rate (3, 8, 9, 11). This might be overcome by the combined use with doxycycline, which acts more slowly (2) albeit reliably. However, such a combination cannot be recommended without knowledge about the pharmacodynamic interaction of the compounds in the target parasite, P. falciparum, the subject of these investigations.

The studies were carried out at the Malaria Clinic of Mae Hong Son, northern Thailand, in the framework of the monitoring program of drug sensitivity of the Malaria Division, Ministry of Public Health. Malaria is hypoendemic in the area, but many patients come from neighboring Myanmar or have contracted the infection there (13).

The World Health Organization (WHO) in vitro microtest system MARK II (18) was employed in the sensitivity tests. It is based on assessment of the inhibition of schizont maturation (15). The predosed microtiter plates (8-by-12-well Falcon 3070; Becton Dickinson) for artemisinin, doxycycline, and their combinations were prepared at the Department of Specific Prophylaxis and Tropical Medicine, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria. The artemisinin plates (ART) contained the compound in a concentration range of 3- to 3,000-nmol/liter (0.847 to 847 ng/ml) of blood-medium-mixture (BMM). The concentration range of doxycycline (DOX-1) was 100 to 100,000 nmol/liter (0.044 to 44.45 μg/ml) of BMM. The plates with mixtures of artemisinin and doxycycline contained artemisinin at fixed concentrations of either 3 nmol/liter (0.847 ng/ml), corresponding to approximately a 13% effective concentration (EC13) (DOX-2), or 30 nmol/liter (8.470 ng/ml) of BMM, corresponding to approximately EC79 (DOX-3), and doxycycline over the range of 100 to 100,000 nmol/liter (0.044 to 44.45 μg/ml) of BMM. The artemisinin used for the preparation of the plates was provided by the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Beijing, People’s Republic of China. Doxycycline was obtained from SIGMA (D-9891, Lot 22H0119).

The parasite isolates came from patients suffering from uncomplicated monoinfections with P. falciparum with an asexual parasite density of 1,000 to 80,000/μl of blood. Recent treatment with antimalarials was an exclusion criterion. The blood samples for the sensitivity tests were drawn from the fingertip by sterile, heparinized micropipettes and processed according to the microtest methodology (15, 18).

The preincubation (asexual) parasite density was assessed according to the WHO standard method (19). The schizont counts in the thick films of the test were read on the basis of 200 asexual parasites per well (15). A summary evaluation of the individual tests was made on the basis of the end points of schizont maturation (cutoff point). The grouped data were used for calculating the geometric mean cutoff concentration (GMCOC) for each category. The method of Litchfield and Wilcoxon (5) in its computer adaptation (17) was employed for the analysis of the log-normally distributed artemisinin data. Nonlinear analysis (Hoerl regression) was used for processing the log-transformed concentration and probit-transformed response data obtained with doxycycline and its mixtures with artemisinin. Individual EC50s, EC90s, and EC99s were also calculated. Student’s t test was employed for the comparison of means. Correlation was tested by the Spearman rank and Pearson methods. Expected inhibition for the combination lines was calculated on the basis of the response to the single components, assuming fully additive activity and independent action of the two drugs. Ratios of observed/expected inhibitory concentrations of < 1 indicate higher-than-additive activity.

Parallel tests with all four lines (ART, DOX-1, DOX-2, and DOX-3) were successfully performed with 31 P. falciparum isolates. The basic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The correlation coefficients of all regressions are >0.98, and the χ2 values for heterogeneity are well below the permissible limits, indicating a good fit of the data points to the mathematically derived regression lines. The sensitivity to artemisinin, with an EC50 of 11.31 nM (3.19 ng/ml), EC90 of 52.13 nM (14.72 ng/ml), and GMCOC of 69.10 nM (19.51 ng/ml), closely resembled the status of the previous year (23). The EC50 for doxycycline alone (DOX-1) was 14,272 nM (6.34 μg/ml), compared to 8,001 nM (3.56 μg/ml) when the drug was associated with 3 nM (0.85 ng/ml) artemisinin (DOX-2). The EC90 for DOX-1 was 39,482 nM (17.55 μg/ml), compared to 21,890 nM (9.73 μg/ml) with DOX-2 and 5,011 nM (2.23 μg/ml) when doxycycline was associated with 30 nM (8.47 ng/ml) artemisinin (DOX-3). The GMCOC for DOX-1 was 70,179 nM (31.19 μg/ml), compared to 30,208 nM (13.43 μg/ml) for DOX-2 and 1,870 nM (0.83 μg/ml) for DOX-3.

TABLE 1.

In vitro response parameters for artemisinin, doxycycline, and for mixtures of artemisinin and doxycycline with P. falciparum isolates from Mae Hong Son, Thailand, 1997 (results from 31 isolates)a

| Parameter | Concn (nm) | Value for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemisinin | Doxycycline | DOX-2b | DOX-3c | ||

| % SMI (mean) | 3 | 12.76 | |||

| 10 | 45.00 | ||||

| 30 | 82.16 | ||||

| 100* | 96.04 | 3.63 | 7.89 | 67.38 | |

| 300* | 99.73 | 5.43 | 10.26 | 74.79 | |

| 1,000* | 100.00 | 11.22 | 19.05 | 78.11 | |

| 3,000* | 100.00 | 14.44 | 28.34 | 84.60 | |

| 10,000* | 24.30 | 67.84 | 96.73 | ||

| 30,000* | 90.84 | 99.61 | 100.00 | ||

| 100,000* | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | ||

| Slope | 3.2735 | ||||

| r | 0.9967 | 0.9917 | 0.9979 | 0.9865 | |

| χ2 obs. | 0.439 | 4.860 | 0.380 | 0.112 | |

| χ2 max. permitted | 9.488 | 10.070 | 11.070 | 9.488 | |

| EC50 (nM) | 11.31 | 14,727 | 8001 | ||

| EC90 (nM) | 52.13 | 39,482 | 21,890 | 5,011 | |

| EC99 (nM) | 181.19 | 63,299 | 25,034 | 13,529 | |

| GMCOC (nM) | 69.10 | 70,179 | 30,208 | 1,870 | |

SMI, inhibition of schizont maturation; GMCOC, geometric mean cutoff concentration of schizont maturation; asterisk, value reflects also the doxycycline concentration in DOX-2 and DOX-3; obs., observed; max., maximum.

ART (3 nM) plus DOX.

ART (30 nM) plus DOX.

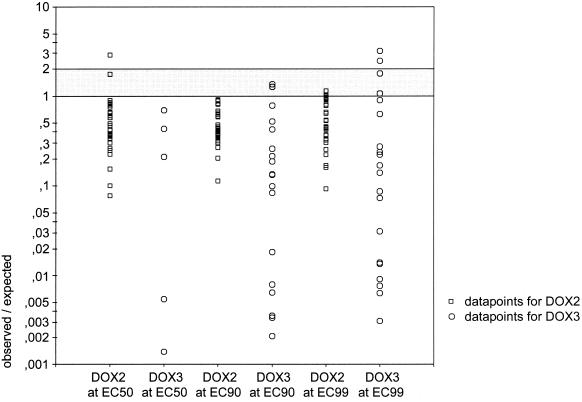

Spearman rank (rS) and Pearson (rp) tests failed to show a significant correlation between the activities of doxycycline and artemisinin at the EC50 level (rS = 0.248 and P = 0.179; rp = 0.147 and P = 0.439) and at the EC90 level (rS = 0.305 and P = 0.095; rp = 0.165 and P = 0.376). For DOX-2, the observed EC50s, EC90s, and EC99s of the individual isolates were significantly lower than the expected values (t(EC50) = 2.7582 and P < 0.01; t(EC90) = 6.5138 and P < 10−7; t(EC99) = 6.7891 and P < 10−7). For DOX-3 the comparison was restricted to isolates with an EC84 (probit 1) for artemisinin of ≤30 nM artemisinin. Also here, the observed EC90s and EC99s were significantly lower than the expected concentrations (t(EC90) = 4.6030 and P < 0.001; t(EC99) = 3.9456 and P < 0.001). The data points for observed/expected EC50s, EC90s, and EC99s with DOX-2 and DOX-3 are shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Observed/expected EC50s, EC90s, and EC99s for P. falciparum isolates (n = 31) exposed to mixtures of doxycycline and 3 nM artemisinin (DOX-2) or doxycycline and 30 nM artemisinin (DOX-3). Values of <1 denote synergism; 1 denotes fully additive activity; values of >1 and <2 denote partially additive activity.

Clinical observations with combined medication with doxycycline and artemisinin or its derivatives (1, 7, 10, 22) have yielded, so far, ambiguous results, but in none of the studies were the drugs employed according to the conventional principles of blood schizontocidal treatment in malaria. The results of our studies would justify a new and thorough look at the therapeutic usefulness of such combinations.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bich, N. N., P. J. De Vries, H. Van Thien, T. H. Phong, L. N. Hung, T. A. Eggelte, T. K. Anh, and P. A. Kager. 1996. Efficacy and tolerance of artemisinin in short combination regimens for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 55:438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Budimulja, A. S., Syafruddin, P. Tapchaisri, P. Wilairat, and S. Marzuki. 1997. The sensitivity of Plasmodium protein synthesis to prokaryotic ribosomal inhibitors. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 84:137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bwijo, B., M. H. Alin, N. Abbas, W. Wernsdorfer, and A. Bjorkman. 1997. Efficacy of artemisinin and mefloquine combinations against Plasmodium falciparum. In vitro simulation of in vivo pharmacokinetics. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2:461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ketrangsee, S., S. Vijaykadga, P. Yamokgul, S. Jatapadma, K. Thimasarn, and W. Rooney. 1992. Comparative trial on the response of Plasmodium falciparum to halofantrine and mefloquine in Trat Province, eastern Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 23:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litchfield, J. T., and F. Wilcoxon. 1949. A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 96:99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Looareesuwan, S., D. E. Kyle, C. Viravan, S. Vanijanonta, P. Wilairatana, P. Charoenlarp, C. J. Canfield, and H. K. Webster. 1992. Treatment of patients with recrudescent falciparum malaria with a sequential combination of artesunate and mefloquine. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 47:794–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Looareesuwan, S., C. Viravan, S. Vanijanonta, P. Wilairatana, P. Charoenlarp, C. J. Canfield, and D. E. Kyle. 1994. Randomized trial of mefloquine doxycycline, and artesunate doxycycline for treatment of acute uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 50:784–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maeno, Y., T. Toyoshima, H. Fujioka, Y. Ito, S. R. Meshnick, A. Benakis, W. K. Milhous, and M. Aikawa. 1993. Morphologic effects of artemisinin in Plasmodium falciparum. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 49:485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meshnick, S. R., Y. Z. Yang, V. Lima, F. Kuypers, S. Kamchonwongpaisan, and Y. Yuthavong. 1993. Iron-dependent free radical generation from the antimalarial agent artemisinin (qinghaosu). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1108–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Na Bangchang, K., T. Kanda, P. Tipawangso, A. Thanavibul, K. Suprakob, M. Ibrahim, Y. Wattanagoon, and J. Karbwang. 1996. Activity of artemether-azithromycin versus artemether-doxycycline in the treatment of multiple drug resistant falciparum malaria. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 27:522–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen, D. S., B. H. Dao, P. D. Nguyen, V. H. Nguyen, N. B. Le, V. S. Mai, and S. R. Meshnick. 1993. Treatment of malaria in Vietnam with oral artemisinin. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 48:398–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nosten, F., F. ter Kuile, T. Chongsuphajaisiddhi, C. Luxemburger, H. K. Webster, M. Edstein, L. Phaipun, K. L. Thew, and N. J. White. 1991. Mefloquine resistant falciparum malaria on the Thai Burmese border. Lancet 337:1140–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Somboon, P., A. Aramrattana, J. Lines, and R. Webber. 1998. Entomological and epidemiological investigations of malaria transmission in relation to population movements in forest areas of north west Thailand. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 29:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wernsdorfer, W. H. 1994. Epidemiology of drug resistance in malaria. Acta Trop. 56:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wernsdorfer, W. H. 1980. Field evaluation of drug resistance in malaria. In vitro micro test. Acta Trop. 37:222–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wernsdorfer, W. H., and D. Payne. 1991. The dynamics of drug resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Pharmacol. Ther. 50:95–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wernsdorfer, W. H., and M. G. Wernsdorfer. 1995. The evaluation of in vitro tests for the assessment of drug response in Plasmodium falciparum. Mitt. Österr. Ges. Tropenmed. Parasitol. 17:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization. 1990. World Health Organization document MAP/87.1, Rev. 1. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 19.World Health Organization. 1991. Basic malaria microscopy, vol. 1. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 20.World Health Organization. 1998. The use of artemisinin and its derivatives as anti-malarial drugs. W. H. O./MAL/98.1086. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 21.World Health Organization. 2000. World Health Organization Expert Committee on Malaria. WHO Tech. Rep. Ser. 892:1–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ye, Z., and K. Van Dyke. 1994. Interaction of artemisinin and tetracycline or erythromycin against Plasmodium falciparum in vitro. Parasite 1:211–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zatloukal, C., B. Woitsch, H. Noedl, S. Prajakwong, G. Wernsdorfer, and W. H. Wernsdorfer. 1998. Longitudinale Beobachtungen über die Artemisininempfindlichkeit von Plasmodium falciparum in Thailand. Mitt. Österr. Ges. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 20:165–170. [Google Scholar]