Abstract

BMS 284756 penetrated well into inflamed meninges (44% ± 11%) and produced good bactericidal activity (−0.82 ± 0.22 Δlog10 CFU/ml · h) in the treatment of experimental meningitis in rabbits due to a penicillin-sensitive strain. BMS 284756 monotherapy had a greater potency than the standard regimen of ceftriaxone and vancomycin (−0.49 ± 0.08 Δlog10 CFU/ml · h) against a penicillin-resistant strain (MIC, 4 mg/liter). Even against a penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain, BMS 284756 showed good bactericidal activity (−0.52 ± 0.12 Δlog10 CFU/ml · h). The antibacterial activity of BMS 284756 was confirmed by time-killing assays over 8 h in vitro.

The global increase of drug-resistant pneumococci has complicated the treatment of pneumococcal infections. In the United States, a recent survey showed resistance rates around 51%, with 33% of the strains having intermediate resistance (10). Additional resistance to cephalosporins has further limited the therapeutic options for penicillin-resistant isolates. Despite the limitations of the actual therapeutic modalities, β-lactams remain the drugs of choice for pneumococcal diseases, except when their penetration into infected tissues is limited, as is the case in meningitis. Actually, a combination of vancomycin and a cephalosporin is recommended for meningitis due to resistant strains (11). However, a reliable monotherapy would represent a major advantage.

Among recently developed compounds, BMS 284756, a new quinolone, is one of the most promising, especially due to its activity against many gram-positive microorganisms, including penicillin-resistant pneumococci (R. N. Jones, M. A. Pfaller, D. J. Beidenbach, and M. Stillwell, 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1042, 2000; R. N. Jones, M. A. Pfaller, and M. Stillwell, 40th ICAAC, abstr. 1043, 2000). Little is known about the penetration of BMS 284756 into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The aim of this study was to investigate the penetration of BMS 284756 into the subarachnoid space and to test its bactericidal activity against penicillin-sensitive, penicillin-resistant, and penicillin- and quinolone-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model. The standard regimen consisted of ceftriaxone monotherapy for the penicillin-sensitive strain and ceftriaxone combined with vancomycin for the penicillin-resistant strain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rabbit meningitis model.

The meningitis model, originally described by Dacey and Sande (6), was slightly modified. The experimental protocol was accepted by the local ethical committee (Veterinäramt des Kantons Bern). Young New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2 to 2.5 kg were anesthetized by intramuscular injections of ketamine (30 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg) and were immobilized in stereotactic frames for induction of meningitis and CSF sampling. An inoculum containing approximately 105 CFU of either penicillin-sensitive, penicillin- resistant, or penicillin- and quinolone-resistant pneumococci serotype 6 was directly injected into the cisterna magna. The pneumococcal strain (WB4) was originally isolated from a patient with pneumonia at the University Hospital of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. The penicillin-sensitive strain was kindly provided by the Institute for Infectious Diseases, Bern, Switzerland. The MICs for the penicillin-resistant strain were as follows (in milligrams per liter): penicillin, 4; ceftriaxone, 0.5; vancomycin, 0.12 to 0.25; and BMS 284756, 0.06. The MICs for the penicillin-sensitive strain were as follows: penicillin, 0.05; ceftriaxone, 0.05; and BMS 284756, 0.06. The quinolone-resistant strain was obtained by sequential exposure of parental strain WB4 to trovafloxacin. The MICs were as follows: penicillin, 4; ceftriaxone, 0.5; vancomycin, 0.12 to 0.25; trovafloxacin, 4; ciprofloxacin, 32; BMS 284756, 0.5. MICs were determined by serial dilution in broth.

A long-acting anesthetic (ethylcarbamate [urethane]; 3.5 g/rabbit) was injected subcutaneously, and animals were returned to their cages. A catheter was introduced 14 h later into the femoral artery for serum sampling, and the cisterna magna was punctured again for periodic CSF sampling before and 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after initiation of therapy. Anesthesia was performed by repetitive injections of pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal). Blood samples for measuring BMS 284756 were drawn at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8 h after drug administration in rabbits. Antibiotics were administered through a peripheral ear vein as bolus injections at the following doses: BMS 284756, 30 mg/kg of body weight; ceftriaxone, 125 mg/kg; vancomycin, 20 mg/kg. Ceftriaxone and BMS 284756 were injected once at hour 0 and vancomycin was injected at hours 0 and 4 as described by Friedland et al. (7), Gerber et al. (8), and Cottagnoud et al. (5). Untreated controls received saline. All antibiotics and anesthetic drugs were purchased commercially, except for BMS 284756, which was kindly provided by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company.

Bacterial titers were measured by 10-fold serial dilutions of CSF samples, plated on blood agar plates containing 5% sheep blood, and incubated overnight at 37°C. In parallel, 20 μl of undiluted CSF samples were plated (limit of detectability, 50 CFU/ml). Comparison between dilutions of CSF was used to exclude significant carryover effects during therapy. The antimicrobial activity of the regimens during the 8-h treatment was calculated by linear regression analysis and expressed as change in log10 CFU per milliliter per hour and as change in viable count over 8 h. A value of 1.7 (log10 of the limit of detectability) was assigned to the first sterile CSF sample, and a value of 0 was assigned to any following sterile sample. The results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. Statistical significance was determined by the Newman-Keuls test.

Measurement of antibiotic levels in CSF.

Antibiotic concentrations in CSF were determined by the agar diffusion method. Standard curves were performed in saline with 5% rabbit serum in order to mimic CSF protein concentration (14). Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 was used as test strain for BMS 284756 (17). The intra- and interday variabilities of this method were less than 10%. The limits of detection were 0.5 mg/liter for vancomycin and 0.12 mg/liter for BMS 284756.

In vitro assays.

Pneumococcal strains (penicillin sensitive, penicillin resistant, and penicillin and quinolone resistant) were grown in C+Y medium (12) to an optical density of 0.3 at 590 nm and then diluted 40-fold to 106 CFU/ml, corresponding to the CSF bacterial titer in rabbits before initiation of therapy. BMS 284756 was added at concentrations corresponding to 1, 5, and 10 times the MIC (MICs, 0.06 mg/liter for the penicillin-sensitive and penicillin-resistant strains and 0.5 mg/liter for the penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain). Bacterial titers were determined at 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h by serial dilution of samples, plated on agar plates containing 5% sheep blood, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results were expressed as means ± standard deviations.

Pharmacokinetic analysis. (i) Descriptive analysis.

Peak CSF drug concentrations and time from drug administration (bolus injection at time 0) to peak concentrations in CSF were taken directly from the concentration-time curves. The areas under the concentration-time curves for serum and CSF up to the last measurable concentration (AUCS0-t and AUCCSF0-t, respectively) were estimated by the linear trapezoidal rule. For the three rabbits without measurements of concentrations in serum, AUCS0-t was set to the average AUCS0-t for rabbits with measurements in CSF and serum. CSF penetration by BMS 284756 (partition coefficient [PCAUC]) was calculated as the ratio AUCCSF0-t /AUCS0-t for each rabbit and also estimated from the population kinetic model (PCM; see below). Descriptive analyses were performed with the software package Splus 5 for UNIX (MathSoft, Inc., Seattle, Wash.).

(ii) Population kinetics model.

A zero-order input (single bolus injection at time 0), first-order elimination, three-compartment model was used to describe the time course of serum and CSF drug concentrations. Both the second (peripheral) and the third (CSF) compartment are linked to the central (serum) compartment (2, 18). The partition coefficient CSF/serum (PCM) is a model parameter. The relevant differential equations defining the population kinetic model are given in the appendix.

(iii) Fitting of the population kinetic model.

A population kinetic model was fitted to all measured plasma and CSF drug concentrations from all animals by using the computer program NONMEM (nonlinear mixed effects modeling; NONMEM Project Group, University of California at San Francisco) (3, 4). Observed concentrations in serum and CSF are modeled as their expected values, as predicted by the kinetic model, plus an independent normally distributed random error, with standard deviations proportional to the expected concentration values (see the appendix for details).

RESULTS

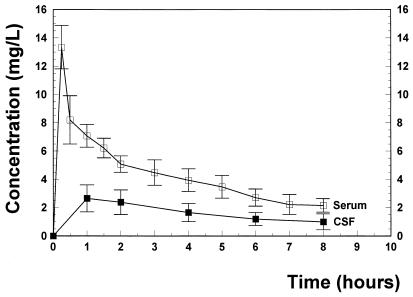

Figure 1 presents the observed serum and CSF concentration-time profiles following the administration of a single intravenous 30-mg/kg BMS 284756 dose. During almost the entire therapy period, BMS 284756 levels remained above the MIC (0.06 mg/liter for the penicillin-sensitive and -resistant strain and 0.5 mg/liter for the quinolone-resistant strain). CSF/MIC ratios ranged between 46 and 18 for the penicillin-sensitive and -resistant strain and between 5.6 and 2.2 for the quinolone-resistant strain. The overall goodness of fit for the population kinetic three-compartment model is excellent. The kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. The penetration of BMS 2842756 was around 44% ± 11%. The killing rates of the different treatment groups are summarized in Table 2. In untreated controls, bacterial titers remained almost constant during 8 h (+0.06 ± 0.10 Δlog10 CFU/ml · h). BMS 284756 produced a highly bactericidal activity against the penicillin-sensitive strain, comparable to the standard regimen (ceftriaxone monotherapy), and sterilized the CSF of 9 of 11 rabbits after 8 h. Even against the penicillin-resistant strain, one injection of 30 mg of BMS 284756 per kg sterilized the CSF of 9 of 11 rabbits. It is interesting that BMS 284756 monotherapy was significantly more efficacious than the standard regimen of ceftriaxone combined with vancomycin. Even against the penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain, BMS 284756 produced a good antibacterial effect, sterilizing the CSF of 5 of 9 rabbits after 8 h.

FIG. 1.

BMS 284756 concentrations in serum and CSF during 8 h after intravenous injection of 30 mg/kg. The concentration of BMS 284756 in CSF remained above the MICs (0.06 and 0.5 mg/liter, respectively) throughout the treatment period.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for BMS-284756 in serum and CSF following the administration of a single 30-mg/kg intravenous bolus dose to rabbits

| Parameter | Mean (SD [%]) |

|---|---|

| Kinetic parameter (descriptive analysis) | |

| AUCS0-ta | 34 (2.3) |

| AUCCSF0-ta | 15 (3.6) |

| PCAUC (%) | 44 (11) |

| Peak concentration in CSF | 2.8 (0.5) |

| Time to peak concentration in CSF | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Population kinetic parameters (kinetic model) | |

| Central volume of distribution (VS) (liters) | 3.1 (2.0) |

| Peripheral volume of distribution (VP) (liters) | 4.6 |

| Intercompartmental clearance between VS and VP (liters/h) | 4.4 |

| Clearance (liters/h) | 0.98 (17) |

| Elimination rate constant (h−1) | 0.32 (6.9) |

| CSF equilibration rate constant (h−1) | 0.85 (16) |

| CSF residence time (h) | 1.2 (23) |

| PCM (%) | 46 (7.3) |

| Residual error (concentrations in serum) | 0.36 |

| Residual error (concentrations in CSF) | 0.31 |

Estimated up to the last measurable concentration (see the text for details).

TABLE 2.

Single-drug and combination therapies against penicillin- and penicillin- and quinolone-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in experimental meningitisa

| Strain type | Antibiotic (no. of strains) | Initial titer (log10 CFU/ml) | Killing rate (Δlog10 CFU/ml ·) | Killing rate/8 h (log10 CFU/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin sensitive | Controls (8) | 6.30 ± 0.51 | + 0.06 ± 0.10 | + 0.34 ± 0.09b |

| BMS 284756 (11) | 5.29 ± 0.79 | − 0.82 ± 0.22 | − 5.47 ± 0.72 | |

| Ceftriaxone (5) | 5.55 ± 0.70 | − 0.90 ± 0.27 | − 5.55 ± 0.72 | |

| Penicillin resistant | Controls (4) | 6.65 ± 0.91 | + 0.12 ± 0.18 | + 0.45 ± 0.32 |

| BMS 284756 (11) | 5.61 ± 0.97 | − 0.75 ± 0.18 | − 5.14 ± 0.96c | |

| Ceftriaxone + vancomycin (7) | 5.96 ± 0.93 | − 0.49 ± 0.08 | − 3.66 ± 0.59 | |

| Penicillin and quinolone resistant | Controls (6) | 5.65 ± 0.57 | + 0.26 ± 0.19 | + 0.48 ± 0.35 |

| BMS 284756 (9) | 5.83 ± 1.20 | − 0.52 ± 0.12 | − 4.50 ± 0.87 |

Data are means ± standard deviations.

P < 0.05 versus all other groups.

P < 0.02 versus value for ceftriaxone plus vancomycin.

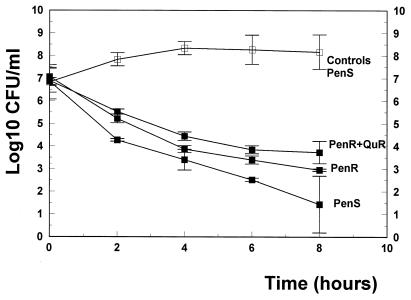

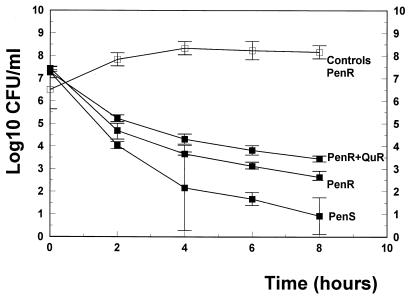

In vitro, BMS 284756 produced excellent bactericidal activity against all strains tested with concentrations above the MIC (5 and 10 times the MIC) in time-killing assays over 8 h (Fig. 2 and 3). Concentrations of 5 and 10 times the MIC led to a dose-dependent decrease of the viable cell count over 8 h (4.6 and 6.3 log10 CFU/ml against the penicillin-sensitive strain and 4.1 and 4.9 log10 CFU/ml against the penicillin-resistant strain). Even against the quinolone-resistant strain, BMS 284756 showed good antibacterial activity in concentrations above the MIC (3.3 and 3.6 log10 CFU/ml, for 5 and 10 times the MIC, respectively).

FIG. 2.

Killing rates of BMS 284756 (▪) in vitro at concentrations corresponding to 5 times the MIC against a penicillin-sensitive strain (PenS), a penicillin-resistant strain (PenR), and a penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain (PenS+QuR). □, untreated controls. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and killing rates are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

FIG. 3.

Killing rates of BMS 284756 (▪) in vitro at concentrations corresponding to 10 times the MIC against a penicillin-sensitive strain (PenS), a penicillin-resistant strain (PenR), and a penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain (PenS+QuR). □, untreated controls. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and killing rates are expressed as means ± standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The continuous spread of penicillin-resistant isolates has jeopardized the successful treatment of pneumococcal diseases by β-lactam antibiotics, underlining the need for alternative therapies. Newer quinolones with extended activity against gram-positive microorganisms are among the most promising candidates.

BMS 284756 is a recently developed des-F(6)-quinolone with an excellent activity against penicillin-sensitive and -resistant pneumococci (Jones et al., 40th ICAAC, abstr. 1042; Jones et al., 40th ICAAC, abstr. 1043). BMS 284756 (800 mg per os) led to maximal peak levels in serum around 15.3 mg/liter in humans (D. Grasela, D. Gaijar, A. Bello, Z. Ge, and L. Christopher, 40th ICAAC, abstr. 2260, 2000) corresponding approximately to levels (13.2 mg/liter) in serum in the rabbit meningitis model obtained after a single 30-mg/kg intravenous dose. PCM, obtained from the kinetic three-compartment model, is close to the average of PCAUC derived from the AUC ratios (46% versus 44%). The doses of ceftriaxone and vancomycin were standard doses that have been used in previous studies in the same model (5, 7, 8) and led to levels in CSF corresponding to those achieved with high doses in humans (1, 16).

In the present study, BMS 284756 produced a pronounced antibacterial activity in vivo against penicillin-sensitive and -resistant strains and sterilized the CSF of the majority of the animals after 8 h. All animals survived in the BMS 284756 groups except for one animal in the penicillin- and quinolone-resistant group. BMS 284756 monotherapy was slightly more potent than the standard regimen (ceftriaxone combined with vancomycin) and superior to trovafloxacin and grepafloxacin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the same animal model (9, 16).

Against the penicillin- and quinolone-resistant strain, BMS 284756 was slightly less efficacious, correlating with the killing rates of BMS 284756 obtained in vitro.

It is interesting that BMS 284756 was more bactericidal against the penicillin-sensitive strain than against the penicillin-resistant strain despite the identical MICs. The underlying mechanism is not clear, but it is reminiscent of the cross-tolerance observed in vancomycin-tolerant pneumococci (13, 15). It is noteworthy that the killing rates over 8 h in vitro seem to have some predictive value regarding the efficacy of BMS 284756 in vivo. The decrease of the viable cell counts in vitro obtained with the highest concentration (10 times the MIC) correlates well with the killing rates over 8 h for the three strains tested in the experimental model (r = 0.992; P = 0.07; P is not significant because only three strains have been tested so far).

The efficacy of BMS 284756 in vitro and in the meningitis model, due to its bactericidal activity and its good penetration into the CSF, deserves further clinical investigation, especially against resistant strains.

Appendix

Pharmacokinetic three-compartment model.

The pharmacokinetic three-compartment model for a generic individual is as follows (2):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

where AS(t) is the amount of drug in the central compartment (serum), AP(t) is the amount of drug in the peripheral compartment, ACSF(t) is the amount of drug in the CSF compartment, CS(t) is the serum drug concentration, and CCSF(t) is the CSF drug concentration at any time (t), VS is the central volume of distribution (in liters), VP is the peripheral volume of distribution, VCSF is the volume of distribution in CSF (in liters), CL is the clearance (in liters per hour), QC is the intercompartmental clearance between central and peripheral compartment (in liters per hour), CLin is the clearance from central to CSF compartment (in liters per hour), CLeq is the equilibration clearance from CSF to central compartment (in liters per hour), keq is the equilibration rate constant from CSF to serum compartment (per hour), teq is the equilibration half-life time in CSF (in hours), MRT is the mean residence time in CSF, and PCM is the CSF/serum partition coefficient. The initial condition at time zero for AS is the initial dose (single bolus injection, 30 mg/kg).

Hierarchical statistical model.

The hierarchical statistical model expressed generically is as follows.

|

where CXij is the drug concentration in compartment X (X = serum or CSF) observed at the jth scheduled time point during the study in the ith individual, fij is a model for the expectation of CXij, conditional on PI, a vector of kinetic parameters for BMS 284756 for the Ith individual, and ɛXij is an independent normally distributed mean zero error with the standard deviation ςX.

|

where Pik is the kth element of PI, gik is a model for its (log) expectation, and ηik is a normally distributed mean zero random effect. The vector θ consists of such population mean parameters as CL, keq, and PCM.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, A. 1997. A critical evaluation of vancomycin for treatment of bacterial meningitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 16:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson, B. J., H. G. Holford, G. A. Woollard, and P. L. S. Chan. 1998. Paracetamol plasma and cerebrospinal fluid pharmacokinetics in children. Br J. Clin. Pharmacol 46:237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beal, S., and L. Sheiner. 1980. The NONMEM system. Am. Stat. 34:118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benett, J. E., and J. C. Wakefield. 1996. A comparison of Bayesian population method with two methods as implemented in commercially available software. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 4:403–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottagnoud, P., F. Acosta, M. Cottagnoud, K. Neftel, and M. G. Täuber. 2000. Synergy between trovafloxacin and ceftriaxone against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2179–2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dacey, R. G., and M. A. Sande. 1974. Effect of probenecid on cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of penicillin and cephalosporin derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6:437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedland, I. R., M. Paris, S. Ehret, S. Hickey, K. Olsen, and G. H. McCracken, Jr. 1993. Evaluation of antimicrobial regimens for treatment of experimental penicillin- and cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1630–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerber, C., M. Cottagnoud, K. Neftel, M. G. Täuber, and P. Cottagnoud. 2000. Evaluation of cefepime alone and in combination with vancomycin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model and in vitro. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:63–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber, C. M., L. Tovar, M. Cottagnoud, K. A. Neftel, M. G. Täuber, and P. Cottagnoud. 2000. Grepafloxacin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.M. R. Jacobs. 1999. Drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: rational antibiotic choices. Am. J. Med. 106(Suppl.):19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan, S. L., and E. O. Mason. 1998. Management of infections due to antibiotic-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:628–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lack, S., and R. D. Hotchkiss. 1960. A study of the genetic material determining an enzyme activity in pneumococcus. Biochem. Biophys. Acta 39:508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCullers, J. A., B. K. English, and R. Novak. 2000. Isolation and characterization of vancomycin-tolerant Streptococcus pneumoniae from the cerebrospinal fluid of a patient who developed recrudescent meningitis. J. Infect. Dis. 181:369–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nau, R., K. Kaye, M. Sachdeva, E. Sande, and M. G. Täuber. 1994. Rifampin for the therapy of experimental pneumococcal meningitis in rabbits. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1186–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novak, R., A. Cauwels, E. Charpentier, and E. Tuomanen. 1999. Identification of a Streptococcus pneumoniae gene locus encoding proteins of an ABC phosphate transporter and a two-component regulatory system. J. Bacteriol. 181:1126–1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodoni, D., F. Hänni, C. M. Gerber, M. Cottagnoud, K. Neftel, M. G. Täuber, and P. Cottagnoud. 1999. Trovafloxacin in combination with vancomycin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:963–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon, H. J., and E. Y. Yin. 1970. Microbioassay of antimicrobial agents. Appl. Microbiol. 19:573–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang, L., R. Price, F. Aweeka, S. E. Bellibas, and L. B. Sheiner. 2001. Making the most of sparse clinical data by using predictive-model-based analysis, illustrated with a stavudine pharmacokinetic study. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 12:377–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]