Abstract

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major global health challenge, necessitating novel therapeutic approaches. β-carboline alkaloids, natural compounds with anticancer properties, have shown potential to inhibit cancer cell viability. Here, we synthesized β-carboline derivatives and explored their potential as CRC inhibitors.

Methods

The IC50 values of β-carboline derivatives were determined by cell viability assay. The biological effects of the leading candidate were evaluated via cell cycle analysis, proliferation assay, colony formation, apoptosis assay, and reactive oxygen species detection. Mechanistic studies were performed using transcriptomic and proteomic analysis, validated by immunoblotting, pulldown assay, cycloheximide-chasing assay, and co-immunoprecipitation. An in vivo CRC xenograft model was used to assess the efficacy of the leading candidate.

Results

Z-7 was identified as the leading candidate due to its ability to induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in CRC cells. Transcriptomic and proteomic data revealed that Z-7 activated the p53 signaling pathway in p53 wild-type CRC by binding to MDM2 at the RING domain, and inhibiting the E3 ligase activity of MDM2, leading to the reduction of p53 ubiquitination. In vivo study showed Z-7 treatment elevated p53 expression and significantly suppressed tumor growth in xenograft models.

Conclusion

Z-7 is a promising candidate for CRC therapy, particularly in patients with functional p53 and elevated MDM2, warranting further clinical evaluation.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13402-025-01111-3.

Keywords: β-carboline alkaloid, MDM2-p53 pathway, Small-molecule compounds, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide with approximately 1.93 million cases and 0.9 million deaths annually [1]. Given the difficult diagnosis of early stage of CRC, it is always too late for most patients with advanced tumors. Once metastasis occurs, the 5-year survival rate of CRC patients falls to a low of 15% around [2]. The CRC carcinogenesis is very complex and heterogeneous which could be processed through continuous accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations, and finally gives rise to a malignancy under Darwinian selection [3]. It is well established that the inactivation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) and TP53, along with activation of KRAS oncogene triggers the malignant epithelial-mesenchymal transformation in CRC [4, 5].

TP53 is a well-known tumor suppressor gene which responds to DNA damage and repair and induces cell apoptosis and senescence. TP53 mutation is frequently associated with poor clinical outcomes in a myriad of human malignancies and accounts for almost ~ 40% to 50% in CRC [6, 7]. p53, encoded by TP53, is a sequence-specific transcription factor that regulates the expression of downstream genes, such as CDKN1A, BBC3, and BAX whose promoters or enhancers contain a p53 response element, and thereby controls cell proliferation and cell death, as well as several other processes [8, 9]. As a growth suppressor, the expression and activity of p53 is strictly regulated at a very low level. The E3 ubiquitin ligase mouse double minute 2 homolog (MDM2) is a key negative regulator of p53 activity in the absence of stress by targeting it for degradation or preventing its transcriptional activity [10, 11]. However, upon cell stressed by oncogene activation, DNA damage, nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress and other stress, p53 is released from its negative regulators and activated to control the cell transformation [9].

Targeting dysfunctional p53 in tumors has been pursued for cancer treatment [12]. In mutant p53-expressing tumors, the predominant strategy is to restore tumor suppressor function with pharmacological compounds [13, 14] or genetic manipulation [15]. Gendicine, a recombinant human p53 adenovirus, has been approved by the China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA) to treat head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) in combination with radiotherapy via overexpressing the functional p53 [16]. In wild-type (WT) p53 tumor, targeting the negative regulators of p53 with inhibitors has been developed in many ways, including the inhibition of the deregulated or amplified MDM2. Certain compounds block the E3 ligase activity of MDM2 (namely, HLI98, MEL23 and MEL24) can reduce the viability of cells with WT p53, although they have not been developed further for clinical use [17, 18]. Nutlin-3a, a selective inhibitor of MDM2 binding to p53, induced p53 accumulation and suppressed the growth of WT p53-expressing cancer cells of different origin in vitro and in vivo [19]. Based on the structure of Nutlin-3a, a series of MDM2 inhibitors (MDM2i) has been identified and investigated by institutes and big pharma which indicates the potential translation of MDM2i into clinical treatment of various types of cancer with functional p53 and deregulated MDM2 expression [20].

The development of small-molecule compounds is always the most important foundation for the chemotherapy. β-carboline alkaloid extracted from natural products has been reported to be the major active pharmaceutical ingredient and their pharmacological activity has been studied for many years, especially in the anti-tumor field [21]. The restoration of p53 is partially contributed to the cancer cell death induced by β-carboline alkaloid. Flavopereirine (3-ethyl-12 H-indolo[2,3-a]-quinolizinium perchlorate), a natural β-carboline alkaloid extracted from Geissospermum vellosii (Pao pereira), suppresses the growth of CRC through p53 signaling [22]. SP-141 (6-methoxy-1-(naphthalen-1-yl)-9 H-pyrido[3,4-b]indole), derived from pyrido[b]indole, can directly bind to MDM2, inhibit MDM2 expression and induce its autoubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, finally displays anti-tumor activity in breast cancer via stabilizing the p53 [23]. Based on the structure of Eudistomin-type of Indole alkaloid marine natural products, we synthesized a series of novel chiral β-carboline derivatives by taking advantage of photocatalytic enantioselective Minisci reaction [24] and screened out Z-7 as a candidate which significantly inhibited the tumor proliferation. In the present study, we identify Z-7 as a novel MDM2i which inhibits the CRC viability by restoring the p53 function.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture conditions

The human colorectal cell lines HCT116 (RRID:CVCL_0291), HT-29 (RRID:CVCL_0320), DLD1 (RRID:CVCL_0248) and LoVo (RRID:CVCL_0399), the mouse colorectal cell lines CT26 (RRID:CVCL_7254) and MC38 (RRID:CVCL_B288), the human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines PC9 (RRID:CVCL_B260), A549 (RRID:CVCL_0023), SPCA1 (RRID:CVCL_6955), H460 (RRID:CVCL_0459), and H1299 (RRID:CVCL_0060), the human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293T cell line (RRID:CVCL_0063), and the human breast carcinoma cell line MCF-7 (RRID:CVCL_0031) were all sourced from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). The cells were cultured in either Roswell Park Memorial Institute-1640 (RPMI-1640, SH30809, Cytiva, Uppsala, Sweden) or Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, C11995500CP, Gibco, NY, USA) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, FS301–02, TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. All cell lines were tested by STR profiling to verify the authenticity. Additionally, the mycoplasma testing was performed regularly to ensure the absence of mycoplasma contamination.

Cell viability assay

The cytotoxic activity of the compounds was evaluated using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, C0037, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Cells (104 cells/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were then treated with compounds at the concentration of 3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, or 100 μM for 48 hours. After treatment, the medium from adherent cells was carefully removed. Then, 100 μL of complete medium containing 10% CCK-8 reagent was added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 2 hours. The optical density was subsequently measured at 450 nm using a Thermo Varioskan LUX microplate reader (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, C0037, Beyotime) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 500 cells/well in medium containing 2.5 µM of Z-7 or a DMSO control. At 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours post-treatment, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent along with 100 µL of fresh growth medium was added to each well. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour, after which absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Thermo Varioskan LUX microplate reader (Thermo).

Cell colony formation assay

For colony formation assay, 1000 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. After adherence, cells were treated with the indicated concentration of Z-7. The medium was refreshed every four days to sustain the drug concentration. After 15 days, the medium was removed, and cells were washed twice with PBS buffer, and 20% methanol was added to fix the cells for 10 minutes. Following fixation, cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet solution for 20 minutes at room temperature. Excess crystal violet was washed off with water, and the colonies were air-dried before analysis. Image J was used to analyze the colony numbers.

RNA sequencing

RNA sequencing was conducted on HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with Z-7 for 24 hours. The total RNA was extracted and sequenced by Benagen Technology (Wuhan, China). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the reads count data of each sample. Genes showing significant differential expression were identified with the cutoff threshold of foldchange ≥ 2 or ≤ 0.5 and p value < 0.05.

Protein mass spectrometry

Protein mass spectrometry was performed by SpecAlly Life Technology (Wuhan, China). A high-resolution liquid-mass spectrometry (HRL-MS) system was used for the mass spectrometry analysis of the cell samples to obtain the quantitative proteomic information of the samples and to compare the quantitative proteomic differences between the samples, and then to analyze the functional annotations and enrichment analysis of the differential proteins, as well as the analysis of the protein interaction network, to analyze the proteomic characteristics of the samples, and to screen for important proteins related to the differences between the groups.

Apoptosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) detection assay

Apoptosis was assessed using the Apoptosis Detection Kit (640922, BioLegend, San Diego, CA,USA). Briefly, 5 × 105 cells were treated with Z-7 at concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, and 5 μM. After 48 hours, both floating cells and adherent cells were harvested. Cells were then washed with PBS and stained with FITC-Annexin V and 7AAD for 15 min at room temperature in dark. Apoptosis was then detected using the NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). To investigate the involvement of caspases in Z-7 induced apoptosis, cells were treated with various concentration of Z-7 at the presence or absence of the pan caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (HY-16658B, MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and analysed by flowcytometry.

ROS levels in Z-7 treated CRC were detected using the Cellular ROS Assay Kit (Deep Red) (ab185029, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Cell cycle detection assay

1 × 106 cells (HCT116 and HT29) were seeded in 6-well plates and incubated overnight. Cells were then treated with Z-7 at concentrations of 1.25, 2.5 and 5 μM for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were harvested and fixed with 70% ethanol for at least 30 minutes and stained in PBS containing 10 μg/mL propidium iodide (ST511, Beyotime) and 50 μg/mL RNase A (DE111–01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Samples were incubated at 37 °C for 30 minutes in the dark and analysed by the NovoCyte flow cytometer (Agilent Technologies). The data were analyzed by Flow Jo software.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (P0013C, Beyotime) supplemented with protease inhibitors (HY-K0010, MCE) and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 15 min to obtain the clarified protein supernatant. Protein concentration was determined using a BCA assay kit (P0010, Beyotime). Equal amount of protein from each sample were loaded and separated in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels using electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were then transferred to 0.45 µM polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), which were then blocked with 5% skimmed milk (P0216, Beyotime) for 1 hour at room temperature. Subsequently, the PVDF membranes were probed with indicated primary antibody overnight at 4 °C, then washed at least 3 times with TBST buffer and incubated with corresponding secondary antibody (BA1050/BA1054, Boster, Wuhan, China) for 2 hours at room temperature. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (1705061, Bio-Rad) on Invitrogen iBright Imaging Systems (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Antibodies used for western blot analysis included anti-β-Actin (66009–1-Ig, Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA), anti-p53 (2524S, CST, Danvers, MA,USA), anti-HA (66006–2-Ig, Proteintech), anti-PARP (9532T, CST), anti-MDM2 (D260611, Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), anti-Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) (9718T, CST), anti-Cleaved PARP (9541T, CST), anti-P21 (2947T, CST), anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (9664S, CST), anti-Flag (F1804, Sigma, St. Louis, MO,USA), and anti-Myc (2276S, CST).

Animal experiments and evaluation of toxicity

All animal experiments were approved and performed in accordance with the protocols of the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. A2155). Male BALB/c nude mice, aged 6–8 weeks (Beijing Viton Lifestyle Laboratory Animal Technology, China), were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions. HCT116 cells (1 × 107) were injected subcutaneously into the right flanks of the mice. When the tumors attained a size of 50 mm3, mice were randomly divided into 2 groups: control group (injected with PBS), Z-7 treatment group (injected with 5 mg/kg of Z-7). Control and Z-7 were locally injected into the tumor mass every two days, respectively. A caliper was used to measure the length and width of each tumor. The equation of volume = (length×width× width)/2 was used to calculate tumor volumes. After two weeks treatment (a total of 6 injections), the animals were sacrificed, and the xenograft tumors were excised for tumor weight, western blot, and immunohistochemistry analysis. To assess potential toxicity of Z-7, BALB/c mice were orally administered 60 mg/kg of Z-7 or corn oil. After two weeks, major organs, including the heart, liver, lungs, and kidneys, were collected and subjected to hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining for histopathological examination.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Xenograft tumors or organs from animal model were dissected, fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) before being observed by an experienced pathologist (Haihui Huang). The IHC protocol has been thoroughly described in our previous study [25]. p53 (7F5) Rabbit antibody (2527S, CST) was used. Representative images were captured by light microscopy at 20X and 400X.

Molecular docking analysis

In the Pubchem database, the information about Z-7 compound (Pubchem CID: 166069500) was retrieved and downloaded, and the geometry optimization of Z-7 compound was carried out using Schrodinger software. Then we downloaded the information about human MDM2 (ID:4193) from NCBI database, predicted the MDM2 structure using AlphaFlod2 and downloaded the prediction results. Import the MDM2 structure file and the structure file of Z-7 into Schrodinger software and optimize the MDM2 protein, start the docking program and export the molecular docking results.

Cycloheximide chasing assay

HEK-293T cells transfected with pCDH-TP53 were treated with 5 µM of Z-7 for 24 hours, and then were incubated with 10 µg/mL of cycloheximide (HY-12320, MCE) for the indicated durations. Cells were lysed by Laemmli lysis buffer and subjected to western blot analysis.

Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP)

Cells were first co-transfected pCDH-FLAG-MDM2 and pCMV-Myc-TP53 and treated with indicated concentration of Z-7 for 24 hours. Cells were lysed in IP lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40) on ice. After determining lysate concentrations with BCA, 1000 mg of lysate was incubated with the anti-FLAG magnet beads (HY-K0207, MCE) overnight at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitants were washed with IP lysis buffer three times and eluted by incubating with 50 µL of 1×Laemmli lysis buffer at 95 °C for 10 minutes. The elutes were subjected to western blot analysis.

Ubiquitination detection

HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pCDH-TP53, pCDH-FLAG-MDM2, and pCMV-HA-Ub plasmids and treated with indicated concentration of Z-7 for 24 h. Then cells were lysed with lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris pH-8.0, 2% SDS), and incubated at 95 °C for 10 minutes and brief sonication to shear the DNA. This lysate was subsequently diluted tenfold with IP dilution buffer (10 mM Tris pH-8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1%Triton), and incubated at 4 °C for 60 minutes followed by centrifuging at 13000x RCF for 30 minutes at 4 °C. Subsequently, diluted lysate mixed with 10 µL of protein A/G magnetic beads (HY-0202, MCE) and 1 µg of anti-p53 (2524S, CST) was incubated at 4 °C overnight. After the incubation, beads were washed with washing buffer (10 mM Tris pH-8.0, 1 M NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40) three times and eluted with 50 µL of 1×Laemmli lysis buffer at 95 °C for 10 minutes. The elutes were subsequently subjected to western blot analysis.

RNA isolation and RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted by RNA-easy isolation reagent (R701–01, Vazyme) as the manufacturer’s instructions and the concentration was measured by NanoDrop (Thermo). The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed using the HiScript II Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (R223–01, Vazyme). cDNA was then diluted 10-fold and prepared for quantitative PCR according to the ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Q311–02, Vazyme) instructions. The mRNA expression of target genes was analyzed by the 2-ΔΔCt method. Each real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR reaction was performed in triplicate and normalized to the internal reference β-ACTIN. The primers for TP53 (F: 5′- CCTCAGCATCTTATCCGAGTGG-3′, R: 5′- TGGATGGTGGTACAGTCAGAGC-3′), MDM2 (F:5′- TGTTTGGCGTGCCAAGCTTCTC-3′, R:5′- CACAGATGTACCTGAGTCCGATG-3′), BBC3 (F:5′- ACGACCTCAACGCACAGTACGA-3′, R:5′- CCTAATTGGGCTCCATCTCGGG-3′), CDKN1A (F:5′- AGGTGGACCTGGAGACTCTCAG-3′, R:5′- TCCTCTTGGAGAAGATCAGCCG-3′), ACTB (F:5′- CATCCGCAAAGACCTGTACG-3′, R:5′- CCTGCTTGCTGATCCACATC-3′).

Establishment of p53 knock-down cells

p53 knock-down cells were established by lentivirus-mediated delivery of TP53 shRNA. The oligonucleotide (targeting sequence for TP53 shRNA #1: 5′-CACCATCCACTACAACTACAT-3′, TP53 shRNA #2: 5′-GAGGGATGTTTGGGAGATGTA-3′) was synthesized and cloned into pLKO.1-puro. For virus package, constructed plasmid was co-transfected with pMD2.G (12259, Addgene) and psPAX2 (12260, Addgene) into HEK293T cells. After 48 hours, culture medium containing the lentivirus particles was harvested and filtered through a 0.45 μM filter. Target cells were then infected with the viral supernatant in the presence of polybrene. Following the infection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin for selection. After 48 hours of puromycin selection, cells were harvested and evaluated for p53 knock-down efficiency using qPCR and Western blot analysis.

In vitro Z-7 pulldown assay

Z-7 was first tagged with biotin and conjugated to streptavidin magnetic beads (HY-K0208, MCE). Subsequently, Biotin-Z-7-streptavidin magnetic beads complex was incubated with HEK293T cells transfected with the indicated plasmids harvested using NTEN buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP40). After the overnight incubation, beads were then washed 5 times with wash buffer (100 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 2 mM EDTA, 1% NP40, 0.01% SDS), and then the pulldown protein was eluted with SDS sample buffer and subjected to Western blot analysis.

For construction of truncated MDM2 fragments, truncated MDM2 fragments were PCR cloned from pCDH-FLAG-MDM2 with following primers: MDM2-△p53 binding domain, FWR: 5′-GTCAATCAGCAGGAATC-3′, REV: 5′ - CTCTTGTTCCGAAGC-3′; MDM2-△RING, FWR: 5′- CGGGATCCATGGTGAGGAGCAG −3′, REV: 5′ - CCGCTCGAGTAAGGCATTAAGGGGCAAACTAGATTCC −3′; MDM2-△ZF+RING, FWR: 5′- CGGGATCCATGGTGAGGAGCAG −3′, REV: 5′ - ccGCTCGAGTAACCCTGCCTGATACACAGTAAC −3′; MDM2-ZF+RING, FWR: 5′- CGGGATCCACAGATTCATTTGAAGAAGA-3′, REV: 5′ - CCGCTCGAGCTAATGATGATGATG −3′. All fragments were sub-cloned into pCDH-FLAG vector through BamHI and XhoI sites.

Statistical analysis

All in vitro data were present in mean ± SD unless specifically mentioned otherwise and performed at least in triplicate. Statistical analyses were performed by two tailed Student’s t-test, and ANOVA t-test, as appropriate, using GraphPad Prism (Prism 8.0, GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). For all tests, a p value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

β-carboline alkaloid derivative Z-7 inhibited proliferation in CRC cells

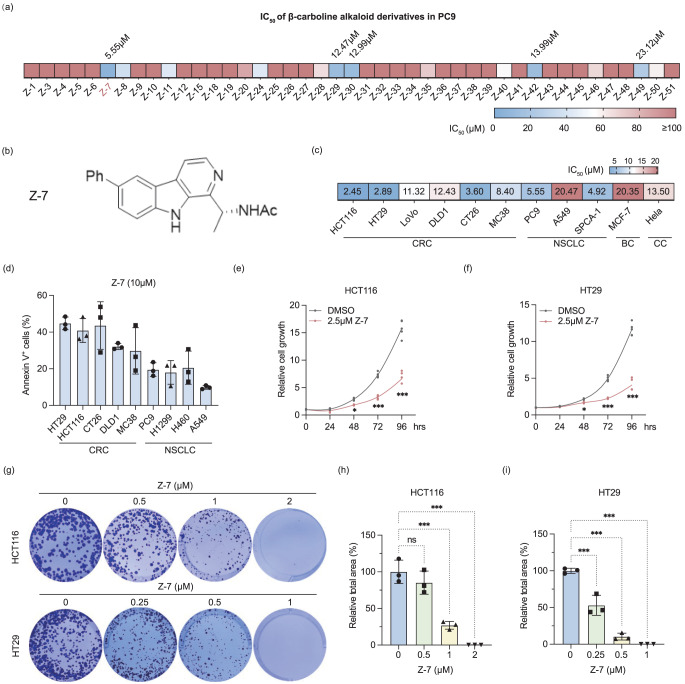

A β-carboline alkaloid derivatives library, consisting of 43 compounds (SI. 1a) was previously constructed via photocatalytic synthesis [24]. To assess the potential anti-tumor properties of these compounds, we initially determined the IC50 values of these candidate compounds using a cell viability assay in human non-small cell lung cancer PC9 cells. Among the compounds tested, Z-7 exhibited the lowest IC50 value of 5.55 µM (Fig. 1a and 1b).

Fig. 1.

Z-7 inhibited cells proliferation and promoted apoptotic rates in CRC cells. (a) The IC50 of 43 β-carboline alkaloid derivatives in NSCLC cell line PC9; (b) The molecular structure of Z-7; (c) The IC50 of Z-7 in different types of cancer; CRC, colorectal cancer; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; BC, breast cancer; CC, cervical cancer; (d) The percentage of Annexin V+ cells in different types of cancers treated with 10 µM Z-7; (e-f) The inhibition of cell proliferation in 2.5 µM Z-7 treated HCT116 (e) and HT29 (f) at different time points; (g-i) Colony formation assays of HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with various concentrations of Z-7; (h) Quantification of colony formation was analyzed by ImageJ (h and i)

To further investigate the anti-tumor efficacy of Z-7, we evaluated its IC50 in various cancer cell lines, including human colorectal cancer cell lines (HCT116, HT29, LoVo, and DLD1), mice colorectal cancer cell lines (CT26 and MC38), human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines (PC9, A549, and SPCA-1), human breast cancer MCF-7 cells, and human cervical cancer Hela cells. Our findings indicated that colorectal cancer cells and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells were more sensitive to Z-7 treatment than other cancer cells (SI. 2a-k, Fig. 1c).

Further analysis was conducted to evaluate the ability of Z-7 to induce apoptosis across different cell lines. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that 10 µM of Z-7 treatment for 24 hours induced higher Annexin V positive cell rate in the colorectal cancer cells than NSCLC cells (Fig. 1d). Then, we explored whether other β-carboline alkaloid derivatives exhibit similar effects on colorectal cancer cells. We examined the cell viability of HCT116 after 10 µM of β-carboline alkaloid derivatives for 48 hours, and the results conclusively demonstrated that Z-7 robustly induced the lowest cell viability (SI. 2 l).

Given the data showed Z-7 inhibits the colorectal cancer cell viability, we further explored the impacts of Z-7 on colorectal cancer cells. Specifically, we evaluated the cells proliferation of HCT116 and HT29 after treated with or without Z-7. Cell proliferation assay showed 2.5 µM of Z-7 significantly impeded the cell proliferation of HCT116 (Fig. 1e) and HT29 (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, a dose-dependent inhibition of cell proliferation and colony formation capability was confirmed in colony formation assay using HCT116 and HT29 (Fig. 1g–i). Collectively, these results underscore the potent inhibition of Z-7 treatment across several cancer cell lines, with particularly pronounced effects observed in CRC.

Z-7 induced G2/M arrest and apoptotic cell death in CRC cells

To investigate the mechanism of Z-7 induced inhibition in CRC, we assessed the potential role of Z-7 in cell cycle. Cell cycle analysis indicated Z-7 induced notable G2/M arrest in both HCT116 and HT29 cancer cells in dose dependent manner, with more pronounced effect observed in HT29 cells (Fig. 2a–d).

Fig. 2.

Z-7 induced the cell cycle arrest and apoptotic cell death in CRC cells. (a-d) Cell cycle analysis of HCT116 (a) and HT29 (b) cells treated with varying concentrations of Z-7 for 24 hours. Quantification of cell cycle phases was analyzed by NovoExpress Software (c and d); (e-g) Flow cytometry analysis of apoptosis (e) in HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with different concentrations of Z-7 for 24 hours. Quantification of Annexin V+ cells percentage in HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with Z-7 (f and g); (h) Western blot analysis of apoptotic markers in HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with Z-7 for 24 hours; (i-j) Quantification of Annexin V+ cells percentage in HCT116 (i) and HT29 (j) following different concentration of Z-7 treatment with or without Z-VAD-FMK (20 µM); Statistical significance is indicated as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

Cell death is critical for reducing cell viability and numbers. Subsequently, we evaluated the cell death induced by Z-7 in CRC via Annexin V and 7AAD. Flow cytometry analysis revealed Z-7 significantly increased Annexin V+ HCT116 and HT29 in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2e–g). Then we conducted western blot to analyze the molecular pathway in Z-7 treated HCT116 and HT29 (Fig. 2h). Elevated phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser139) expression in both Z-7 treated HCT116 and HT29 indicated the Z-7 may cause DNA damage and apoptosis. However, the expression of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 shows difference between HCT116 and HT29. Cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 gradually increased under Z-7 treatment in HCT116 in a dose dependent way while there was not any band of cleaved PARP or cleaved caspase-3 detected in HT29. This result implied that Z-7 induced a caspase-dependent apoptosis in HCT116 while a caspase-independent cell death in HT29. Indeed, the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK can inhibit the Z-7 induced HCT116 cell death (Fig. 2i and SI. 3a) but had no effect on that of HT29 (Fig. 2j and SI. 3b). It is suggesting that Z-7 is able to induce cell death via distinct mechanisms in different CRC cell lines.

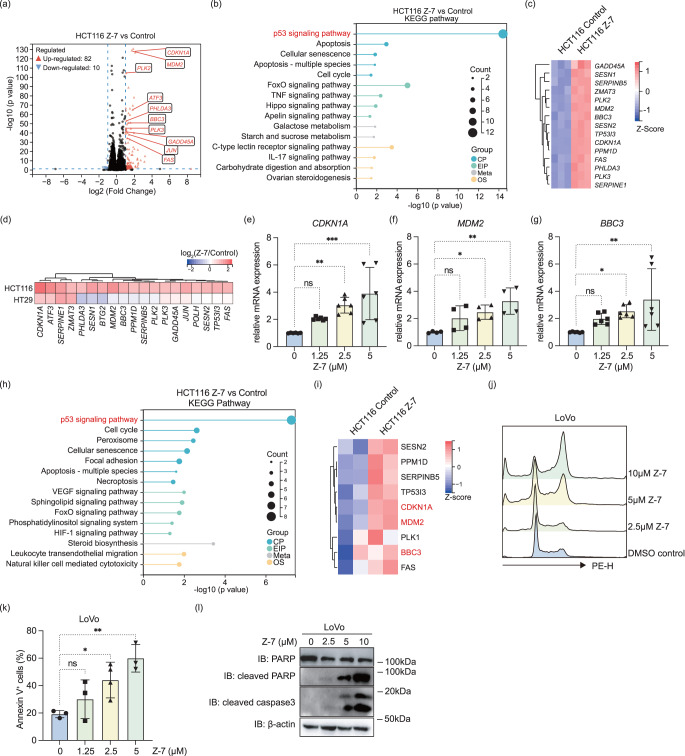

Z-7 activated p53 signaling pathway in p53WT but not p53Mut CRC

To understand the signaling pathways involved in the Z-7 induced CRC inhibition, we conducted RNA-sequencing to further explore the changes in gene expression in Z-7 treated HCT116 and HT29. Interestingly, in the Z-7 treated HCT116, a number of differential expressed genes (DEGs, ≤0.5 fold or ≥ 2 folds, p < 0.05, SI. Table 1) was detected (Fig. 3a), and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis of these DEGs showed p53 signaling pathway was the most prominently up-regulated pathway by Z-7 (Fig. 3b and 3c). In contrast, despite more DEGs were detected in Z-7 treated HT29 (SI. 4a), the p53 signaling pathway was not significantly regulated by Z-7 (p = 0.127) based on the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis (SI. 4b and SI. Table 2). Additionally, most of p53 signaling pathway related genes were highly up-regulated in Z-7 treated HCT116 while not in Z-7 treated HT29 (Fig. 3d). This consequence is reasonable since the TP53 gene is wildtype in HCT116 while mutated in HT29 (TP53 R273H). Following, we confirmed the increased mRNA level of well-known p53 down-stream genes, such as CDKN1A (Fig. 3e), MDM2 (Fig. 3f), and BBC3 (Fig. 3g), in Z-7 treated HCT116 compared to control.

Fig. 3.

p53 signaling pathway was the major pathway regulated by Z-7 in p53WT CRC cells. (a) Volcano plot of DEGs from RNA-seq of HCT116 cells treated with Z-7; (b) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed the DEGs were enriched in the p53 pathway and other cell cycle related pathways; (c) Heatmap of p53 pathway related genes expression in HCT116 treated with Z-7; (d) Heatmap of selected differentially expressed genes in both HCT116 and HT29 cells treated with Z-7; (e-g) qPCR analysis of p53 down-stream genes CDKN1A (e), MDM2 (f), and BBC3 (g) in Z-7 treated HCT116 cells; (h) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed the differential expressed proteins were enriched in the p53 signaling pathway and cell cycle related pathways; (i) Heatmap of p53 pathway related proteins expression in HCT116 treated with Z-7; (j) Cell cycle analysis of LoVo treated with different concentrations of Z-7 for 24 hours; (k) Quantification of Annexin V+ cells percentage in LoVo treated with different concentrations of Z-7; (l) Western blot analysis of apoptotic markers in LoVo cells treated different concentrations of with Z-7 for 24 hours. CP, cellular process; EIP, encrionmental information processing; Meta, metabolism; OS, organismal systems. Statistical significance is indicated as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

Given the importance of p53 signaling pathway in the tumor suppression, we carried out a proteomic analysis and validated the p53 signaling pathway still activated at protein level on the Z-7 treated HCT116. Consistent with the RNA-seq results, quantitative mass spectrum analysis elucidated p53 signaling pathway was the leading pathway regulated by Z-7 according to the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (Fig. 3h and SI. 4c and 4d). In line with previous qPCR results, quantitative mass spectrum analysis revealed a significant up regulation of p21 (encoded by CDKN1A), MDM2, and BBC3 protein (Fig. 3i).

Furthermore, we treated the other p53WT CRC like LoVo with Z-7 and observed p53 downstream genes also up-regulated (SI. 4e-g). The cell cycle of LoVo was also arrested in the G2/M phase (Fig. 3j). Additionally, Z-7 treated LoVo presented similar phenomenon of increased Annexin V+ cells (Fig. 3k and SI. 4 h) and elevated cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3 as HCT116 (Fig. 3l), which indicated Z-7 could function through initiating p53 signaling pathway in p53WT CRC.

p53 signaling pathway was critical for Z-7’s function in p53WT CRC cells

Then we want to know how the Z-7 initiates the p53 activation. Unfortunately, we have not found any information of p53 gene and protein from RNA-Seq and MS data. Next, we checked the mRNA and protein level of TP53 in Z-7 treated p53WT CRC. It seems Z-7 had no effect on the transcription of TP53 in HCT116 (SI. 5a) and LoVo (SI. 5b), but promoted the dose-dependent accumulation of p53 and p21 proteins in HCT116 (Fig. 4a) and LoVo (Fig. 4b). We speculated the augment of p53 protein may contribute to the activating of the p53 signaling pathway and CRC growth inhibition. Hence, we constructed stable TP53-knockdown HCT116 cell lines. Similar with scramble HCT116, Z-7 has no influence on the mRNA level of TP53 in TP53-knockdown HCT116 (Fig. 4c). qPCR analysis of key down-stream genes of p53 signaling pathway showed knockdown of TP53 in HCT116 cells significantly reduced the expressions of CDKN1A (Fig. 4d), BBC3 (Fig. 4e), MDM2 (Fig. 4f) which indicated the expression of p53 is necessary for the Z-7 induced p53 signaling pathway activation.

Fig. 4.

Z-7 inhibited proliferation of p53WT CRC cells through activation of the p53 signaling pathway. (a-b) Western blot analysis of p53 and p21 expression in HCT116 (a) and LoVo (b) after varied concentrations of Z-7 treatment; (c-f) qPCR analysis of TP53 (c) and down-stream genes CDKN1A (d), MDM2 (e), and BBC3 (f) in TP53 knockdown HCT116 cells after varied concentrations of Z-7 treatment; (g) Western blot analysis of apoptotic markers, p53, and p21 in TP53 knockdown HCT116 cells after varied concentrations of Z-7 treatment; (h) Quantification of Annexin V+ cells percentage in TP53 knockdown HCT116 cells after varied concentrations of Z-7 treatment; (i) Cell cycle analysis of TP53 knockdown HCT116 treated with 2.5 µM Z-7. Statistical significance is indicated as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001

Furthermore, Z-7 treated TP53 knockdown HCT116 showed a down-regulation of cleaved PARP and cleaved Caspase 3 compared to that of the scramble (Fig. 4g) which was consistent with the significantly reduction of the Z-7 elicited apoptosis (Fig. 4h and SI. 5c) and cell cycle arrest (Fig. 4i). The above data suggest the Z-7 promotes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via activating the p53-caspase signaling pathway in p53WT CRC.

The mutation of TP53 is account more than half percent of the CRC. Pervious data also showed Z-7 inhibited the proliferation of p53R273H HT29. However, we did not find any changes of p53 and p21 after Z-7 treatment in HT29 (SI. 5d). It is reported ROS play a critical role in the induction of mutant CRC cell death [26]. Indeed, we observed the cellular ROS increased in two p53Mut CRC cells, HT29 and DLD1 (SI. 5e and 5f), after Z-7 treatment. ROS eliminated by 5 mM of NAC reduced Z-7 induced cell death in HT29 (SI. 5 g and 5 h) and DLD1 (SI. 5i and 5j).

Z-7 interfered the MDM2 mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation

Given the above data indicating Z-7 induced p53 protein accumulation in p53WT CRC, we suspected the Z-7 stabilizes p53 by preventing its degradation. Cycloheximide (CHX) chasing assay was applied to evaluate the impact of Z-7 on p53 protein stability. Interestingly, in the p53 over-expressed HEK-293T cells, Z-7 significantly reduce the turnover rate of p53 (Fig. 5a and 5b). The MDM2 is the major E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for p53 stability [27]. To test if Z-7 affects the MDM2 mediated p53 degradation, we assessed the p53 protein level following Z-7 treatment with gradually increased FLAG-MDM2 in 293T cells. The result showed MDM2 over-expression counteracted Z-7 induced p53 accumulation (Fig. 5c), suggesting functional targeting of MDM2 by Z-7. Furthermore, ubiquitination detection assay revealed Z-7 decreased the MDM2 mediated ubiquitination level of p53 (Fig. 5d). These data suggested Z-7 could stabilize p53 via interfering the MDM2 mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation.

Fig. 5.

Z-7 restored p53 protein level through MDM2 mediated p53 ubiquitination by inhibiting E3 ligase function of MDM2. (a) Cyclohexamide (CHX) chasing assay showed Z-7 stabilizing p53 protein level; (b) Statistical data of two independent CHX chasing experiments was generated by using grayscale analysis in ImageJ; (c) Western blot analysis showed over expressing MDM2 can reverse the effects of Z-7 on p53 accumulation; (d) Western blot analysis showed Z-7 down regulated the MDM2 mediated ubiquitin level of p53; (e) The structure of Z-7 tagged with biotin label at the end of acetyl group (named Biotin-Z-7); (f) Competition assay showed the Z-7 physically interacted with MDM2. Whole cell lysis (WCL) of HEK-293T cells with over-expressed FLAG-MDM2 was incubated with or without 100 µM of Z-7 first, and then incubated with streptavidin beads coated with different concentrations of Biotin-Z-7, M for marker; (g) Co-IP showed Z-7 did not interrupt the MDM2-p53 interaction. Briefly, FLAG-MDM2 and Myc-p53 were co-transfected into 293T cells, followed by treatment with or without Z-7. Nutlin-3A served as a positive control. Samples were harvested after treatment, and subjected to immunoprecipitation using an anti-FLAG antibody. (h) Schematic overview of the truncated MDM2 fragments; (i) Pulldown assay showed the Z-7 bound to the RING domain of MDM2. WCL of HEK-293T cells with over-expressed truncated FLAG-MDM2 fragments were incubated with streptavidin beads coated with DMSO or 25 µM of Z-7; (j) Western blot analysis showed Z-7 inhibited MDM2 auto-ubiquitination. FLAG-MDM2 and HA-Ub were co-transfected into 293T cells following Z-7 treatment for 24 hours. Before sampls were harvested, samples were treated with or with 10 µM of MG-132 for 6 hours. Then samples were subjected to ubiquitin analysis and western blot analysis. Statistical significance is indicated as *, p < 0.05

To explore if Z-7 directly interact with MDM2, we performed molecular docking simulation to predict the interaction between Z-7 and MDM2. The result showed that Z-7 may insert into the N-terminal formed hydrophobic pocket of MDM2 by hydrophobic force (SI. 6a). To validate this, we synthesized a biotin-conjugated Z-7 (named Biotin-Z-7, Fig. 5e), and incubated with FLAG-MDM2 over-expressed HEK-293T whole cell lysate, and pulldown with streptavidin magnetic beads subsequently. Notably, western blot analysis of pulldown samples showed Biotin-Z-7 captured FLAG-MDM2 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5f, left panel), and this interaction was competitively inhibited by free Z-7 (Fig. 5f, right panel). These data indicate the Z-7 physically interacts with MDM2.

Subsequently, we investigated whether Z-7 interrupt the interaction between p53 and MDM2. Co-IP was performed by co-transfecting FLAG-MDM2 and Myc-p53 in HEK-293T following Z-7 treatment. Nutlin-3a, a commercial MDM2 inhibitor, was used as a positive control. In line with published study [28], co-immunoprecipitated Myc-p53 was decreased after Nutlin-3a treatment. Interestingly, no significant change in Myc-p53 in Z-7 treated samples indicated Z-7 does not interrupt the MDM2-p53 interaction (Fig. 5g). This data was controversial against computational docking simulation. To further investigate the interaction pattern between Z-7 and MDM2, several plasmids expressing truncated MDM2 fragments were constructed (Fig. 5h) to identify the domain that Z-7 interacts with. Pulldown assay showed MDM2 fragments with RING domain were enriched by Biotin-Z-7, while fragments without RING domain were not, suggesting the RING domain of MDM2 was critical for Z-7 binding (Fig. 5i).

The RING domain was highly related to E3 ligase activity of MDM2, we therefore examined the auto-ubiquitination of MDM2 which regulated its substrate ubiquitin ligase activity [29]. Strikingly, Z-7 treatment significantly attenuated MDM2 auto-ubiquitination (Fig. 5j), indicating the Z-7 bound to the RING domain of MDM2 and inhibited the E3 ligase activity of MDM2.

Intra-tumoral administration of Z-7 restricted CRC growth in vivo

To evaluate the potential therapeutic effect of Z-7 on CRC growth in vivo, we established xenograft HCT116 tumor model in BALB/c nude mice and intratumorally treated them with or without Z-7 (Fig. 6a). The results showed Z-7 administration significantly inhibited the growth of HCT116 in nude mice compared to the control (Fig. 6b) without any loss of body weight (SI. 7a). The weight and size of the tumor are significantly reduced in Z-7 treated mice compared to the control (Fig. 6c and 6d). Furthermore, we detected the p53 protein level in xenograft tumors by western blot (Fig. 6e) and immunohistochemistry (Fig. 6f) and observed Z-7 up-regulated p53 protein level in tumor. At last, we explored the safety of Z-7 in vivo. Cell viability assay showed the IC50 of Z-7 treated PBMC was 44.67 µM (SI. 7b). Subsequently, C57BL/6J mice were administrated by oral gavage with 60 mg/kg of Z-7 every two days for 14 days. H&E staining revealed no significant pathological change in several organs between Z-7 treatment and control group (SI. 7c). Thus, our findings suggest Z-7 is a potential therapeutic drug for colorectal cancer with relative high safety.

Fig. 6.

Z-7 suppressed the growth of HCT116 xenograft model in mice. (a) Schematic overview and timeframe of the animal experiments. BALB/c nude mice were first inoculated subcutaneously with HCT116 cells. From day 6, control or Z-7 was administered via intratumorally injection. All mice were sacrificed on day 16 and the xenografts were excised for further analysis; (b) HCT116 xenograft tumor growth curves of intra-tumoral Z-7 administration in nude mice compared with control group; (c) The weight of HCT116 xenograft tumors in Z-7 treatment group compared with control group; (d) Representative image of HCT116 xenograft tumors with or without Z-7 treatment in nude mice; (e) Western blot analysis of p53 and p21 in HCT116 xenograft tumor treated with or without Z-7 in nude mice. 50 mg of sample was excised from each xenograft tumor, then homogenized and lysed with Laemmli lysis buffer, and subjected to immunoblotting analysis; (f) Immunohistochemistry analysis of p53 expression level in HCT116 xenograft tumor treated with or without Z-7; (g) Proposed model. Z-7 may inhibit MDM2 E3 ligase function, resulting downregulation of p53 ubiquitination level, thereby stabilizing p53 protein and activating relevant downstream proteins in the p53 signaling pathway, eventually leading to inhibit the colorectal cancer progression. Moreover, Z-7 also can increase the ROS level which also promotes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in colorectal cancer. All results are shown as mean±S.E.M (n = 5). *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01,*** p < 0.001

In conclusion, we screened out a potential MDM2-p53 inhibitor from synthesized β-carboline alkaloid derivatives based on the structure of Eudistomin-type of Indole alkaloid. Z-7 restricts CRC growth in vitro and in vivo by inducing cell death and cell cycle arrest. In p53WT CRC, Z-7 induced p53 activation through preventing the MDM2 mediated p53 ubiquitination and degradation. However, in p53Mut CRC, the increased ROS may lead to the cell death (Fig. 6g).

Discussion

Up to now, the improvement of CRC is highly dependent on the chemotherapy which refers to applying certain approved drugs in patients including fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin, and so on [30, 31]. While advances have been made in current chemotherapies, their benefits are limited in clinical practice because of multi drug resistance [32]. Therefore, low-toxicity, highly efficacious, and multi-targets drugs are urgently needed for CRC. β-carboline alkaloid and derivatives have been reported to elicit anti-tumor activity which provides a direction for exploiting novel anti-tumor small-molecule compounds [21]. Based on the structure of Eudistomin-type of Indole alkaloid, our collaborators synthesized a series of derivatives [24] and from that we screened out a potential candidate Z-7 due to its best inhibitory effect on the proliferation of CRC. We observed that Z-7 treatment induced cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in vitro. The analysis of RNA-sequencing and mass spectrometry data demonstrated the p53 signaling pathway was activated by Z-7 treatment in CRC. Mechanically, Z-7 interacted with the RING domain of MDM2 and prevents the MDM2 mediated p53 degradation via inhibiting the E3 ligase activity of MDM2. Moreover, Z-7 treatment significantly elevated the p53 expression in transplanted human CRC and reduced the tumor growth in vivo.

Despite Z-7 is the best choice in all synthesized derivatives, it is still not so good as other reported compounds containing the β-carboline backbone. Ling et al. designed and synthesized a novel series of hybrids from β-carboline and hydroxamic acid and observed the compound 11c displays a lower IC50 (0.83 μM) than Z-7 in HCT116 which displays enhanced anti-tumor activity via regulation of the p53 signaling pathway by targeting both histone deacetylase and DNA [33]. In addition, Liu et al. utilized the structural simplification strategy to construct a novel bis-β-carboline scaffold via “one-pot” condensation-Mannich reaction. Anti-tumor evaluation revealed the compound 3 m displays a lower IC50 (1.19 μM) in the HCT116 compared with Z-7 [34]. Certain optimization of Z-7 according to the difference between Z-7 and other effective compounds might be helpful to create some novel small-molecules with higher anti-tumor bioactivity.

In our study, the treatment of Z-7 activated the p53 signal pathway without any change of TP53 mRNA level indicated Z-7 may influence p53 protein stability. Subsequently, we identify MDM2 is the direct target of Z-7. As an E3 ligase, MDM2 mediates the p53 degradation through proteasome [11]. As a downstream gene of p53, MDM2 and p53 form a negative-feedback loop to fine-tune the intensity of p53 activation. However, the gene amplification of MDM2 is observed in a myriad of human tumors [35, 36], especially in leukemias [37], sarcoma [38], and melanomas [39], which suppresses the expression of p53 and impairs relevant anti-tumor effect. Recently, a comprehensive systematic review pointed out the potential of MDM2 inhibitors [40]. The first potent and selective small-molecule MDM2 antagonist, the Nutlin-3A, were identified from a class of cis-imidazoline compounds and blocked the MDM2-p53 interaction [19]. Intriguingly, our data showed, unlike the Nutlin-3A, Z-7 does not interrupt the MDM2-p53 binding. Instead, Z-7 binds to the RING domain of MDM2 and inhibits MDM2 E3 ligase activity, thereby reducing p53 ubiquitin level and stabilizing p53 protein. However, our current data did not provide direct evidence to confirm whether RING domain binding alone underlies the loss of E3 activity of MDM2. One possible mechanism is that binding of Z-7 to MDM2’s RING domain may hinder the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme recruitment. Further investigation is warranted to elucidate this mechanism in detail.

Platinum drugs, such as oxaliplatin, are the mainstay of CRC chemotherapy. Similar with Z-7, oxaliplatin partially attributed to its capacity to induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis which arise from DNA damage and activated p53 pathway [41]. However, there are approximately 40%-60% of CRC patients carry TP53 gene mutations [42] which confers CRC resistance to platinum drugs. Remarkablely, Z-7 treatment also inhibited p53 mutant CRC growth independent of p53 signaling. We still need to understand why Z-7 can function independent of p53. One possible reason may involve increased ROS level, similar to the impact of Gallium complex K6 in p53 mutant CRC cells, which induces DNA damage and cell death [26]. Indeed, we also observed the DNA damage in Z-7 treated HT29 and identified the critical role of ROS in the HT29 and DLD1 cell death after Z-7 treatment. In the context of cancer, ROS levels can function as a double edge sword: moderate ROS may be vital for tumor cell progression and survival, while excessive ROS could overwhelm antioxidant defenses, resulting in irreversible damage and cell death [43]. Our findings suggest Z-7 may shilf the balance towards lethal ROS accumulation. This ROS-induced cell death may represent a potential therapeutic target for overcoming the chemoresistance in CRC patients with p53 mutations. Further research is need to elucidate the molecular mechanism between Z-7 and the ROS pathway.

Given the Z-7 actives the p53 signaling pathway in vitro, we try to explore the application of Z-7 in vivo to be an anti-tumor drug. In nude mice, we observed Z-7 has effects on the HCT116 tumor growth by intratumor administration while not by oral administration. However, in the immunocompetent mice, oral administration of Z-7 can reduce the B16 tumor growth which is even resistant to the Z-7 treatment in vitro (data not shown) which reflects the importance of the anti-tumor immunity induced by Z-7. Several research have mentioned the MDM2-p53 pathway plays a critical role in the immune system. It is reported that p53 plays a role in murine CD4+ T cell proliferation and apoptosis [44, 45], and p53 restricts the M2 polarization of macrophage via c-Myc inhibition [46]. Intra-tumoral injection of Nutlin-3a in the EL4 and B16 bearing mice caused the p53 mediated immunogenic cell death which induced anti-tumor CTL (Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte) response in WT mice while not in the Rag1-/- immunodeficient mice [47]. Further study investigated that MDM2 is a key factor for infiltrated CD8+ T cell survival in the tumor microenvironment. MDM2 inhibitor APG115 can stabilize the p53 and increase MDM2 expression in T cells which enhanced the T cell survival in tumor bearing mice and inhibited tumor growth [48]. These works indicated Z-7 may synergize with the immunotherapy to cure the tumor.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

F.Z., C.C., S.W., and H.X. developed the initial idea, designed experiments, and analyzed the results. Z.F and S.W. designed and synthesized the compounds. F.Z. and C.C. carried out the major experiments. H.H., Y.K., and X.L. performed animal and IHC experiments. W.C. and Y.Z. assisted with the bioinformatics analysis. Z.X. offered perspectives on experimental designs and data analysis. F.Z., C.C., and H.X. drafted the manuscript. T.X. and H.X. supervised the research work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82273208 to H.X., 82173066 to T.X.), the Guangdong University Characteristic Innovation Project (Natural Science 2022KTSCX222 to H.X.), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20220818101601004 to H.X., JCYJ20210324101810028 to S.W.), and 2024 Hospital-level Clinical Research Key Project (20243357014 to T.X.).

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethical approval

These current animal studies were approved by and performed in accordance with the protocols and guidelines of the institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC) of the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. A2155).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Fanbin Zeng and Cheng Chen contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Shouguo Wang, Email: shouguo.wang@szu.edu.cn.

Tian Xiao, Email: txiao@szu.edu.cn.

Houjun Xia, Email: xiahoujun@suat-sz.edu.cn.

References

- 1.F. Bray, M. Laversanne, H. Sung, J. Ferlay, R.L. Siegel, I. Soerjomataram, A. Jemal, CA Cancer. J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024). 10.3322/caac.21834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.R.L. Siegel, K.D. Miller, S.A. Fedewa, D.J. Ahnen, R.G.S. Meester, A. Barzi, A. Jemal, CA Cancer. J. Clin. 67, 177–193 (2017). 10.3322/caac.21395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.T. Heide, J. Househam, G.D. Cresswell, I. Spiteri, C. Lynn, M. Mossner, C. Kimberley, J. Fernandez-Mateos, B. Chen, L. Zapata, C. James, I. Barozzi, K. Chkhaidze, D. Nichol, V. Gunasri, A. Berner, M. Schmidt, E. Lakatos, A.M. Baker, H. Costa, M. Mitchinson, R. Piazza, M. Jansen, G. Caravagna, D. Ramazzotti, D. Shibata, J. Bridgewater, M. Rodriguez-Justo, L. Magnani, T.A. Graham, A. Sottoriva, Nature 611, 733–743 (2022). 10.1038/s41586-022-05202-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.E.R. Fearon, Annu. Rev. Pathol. 6, 479–507 (2011). 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.N., Cancer genome atlas. Nature 487, 330–337 (2012). 10.1038/nature11252

- 6.T. Takayama, K. Miyanishi, T. Hayashi, Y. Sato, Y. Niitsu, J. Gastroenterol. 41, 185–192 (2006). 10.1007/s00535-006-1801-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A.I. Robles, J. Jen, C.C. Harris, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6 (2016). 10.1101/cshperspect.a026294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.A.J. Levine, Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 471–480 (2020). 10.1038/s41568-020-0262-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.E.R. Kastenhuber, S.W. Lowe, Cell. 170, 1062–1078 (2017). 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.M.H. Kubbutat, S.N. Jones, K.H. Vousden, Nature 387, 299–303 (1997). 10.1038/387299a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Y. Haupt, R. Maya, A. Kazaz, M. Oren, Nature 387, 296–299 (1997). 10.1038/387296a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.S. Peuget, X.L. Zhou, G. Selivanova, Nat. Rev. Cancer 24, 192–215 (2024). 10.1038/s41568-023-00658-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.H. Ramos, M.I.L. Soares, J. Silva, L. Raimundo, J. Calheiros, C. Gomes, F. Reis, F.A. Monteiro, C. Nunes, S. Reis, B. Bosco, S. Piazza, L. Domingues, P. Chlapek, P. Vlcek, P. Fabian, A.T. Rajado, A.T.P. Carvalho, R. Veselska, A. Inga, E.M.T. Pinho, L. Saraiva, Cell. Rep. 35, 108982 (2021). 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.M. Hiraki, S.Y. Hwang, S.G. Cao, T.R. Ramadhar, S. Byun, K.W. Yoon, J.H. Lee, K. Chu, A.U. Gurkar, V. Kolev, J.M. Zhang, T. Namba, M.E. Murphy, D.J. Newman, A. Mandinova, J. Clardy, S.W. Lee, Chem. Biol. 22, 1206–1216 (2015). 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.07.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A. Ventura, D.G. Kirsch, M.E. McLaughlin, D.A. Tuveson, J. Grimm, L. Lintault, J. Newman, E.E. Reczek, R. Weissleder, T. Jacks, Nature 445, 661–665 (2007). 10.1038/nature05541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Y. Xia, X. Li, W. Sun, Curr. Gene. Ther. 20, 127–141 (2020). 10.2174/1566523220999200731003206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Y. Yang, R.L. Ludwig, J.P. Jensen, S.A. Pierre, M.V. Medaglia, I.V. Davydov, Y.J. Safiran, P. Oberoi, J.H. Kenten, A.C. Phillips, A.M. Weissman, K.H. Vousden, Cancer Cell. 7, 547–559 (2005). 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A.G. Herman, M. Hayano, M.V. Poyurovsky, K. Shimada, R. Skouta, C. Prives, B.R. Stockwell, Cancer Discov. 1, 312–325 (2011). 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.L.T. Vassilev, B.T. Vu, B. Graves, D. Carvajal, F. Podlaski, Z. Filipovic, N. Kong, U. Kammlott, C. Lukacs, C. Klein, N. Fotouhi, E.A. Liu, Science 303, 844–848 (2004). 10.1126/science.1092472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.M. Konopleva, G. Martinelli, N. Daver, C. Papayannidis, A. Wei, B. Higgins, M. Ott, J. Mascarenhas, M. Andreeff, Leukemia 34, 2858–2874 (2020). 10.1038/s41375-020-0949-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.B. Luo, X.Q. Song, Eur. J. Criminol. Med. Chem. 224 (2021). 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113688 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.J.M. Li, Y.C. Huang, Y.H. Kuo, C.C. Cheng, F.C. Kuan, S.F. Chang, Y.R. Lee, C.C. Chin, C.S. Shi, Cancers 11 (2019). 10.3390/cancers11071034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.W. Wang, J.J. Qin, S. Voruganti, K.S. Srivenugopal, S. Nag, S. Patil, H. Sharma, M.H. Wang, H. Wang, J.K. Buolamwini, R. Zhang, Nat. Commun. 5, 5086 (2014). 10.1038/ncomms6086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.M.P. Luo, Y.J. Gu, S.G. Wang, Chem. Sci. 14, 251–256 (2023). 10.1039/d2sc05313f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.H.J. Xia, B.L. He, C.Y. Wang, H.L. Zhang, G.Z. Ge, Y.X. Zhang, L.B. Lv, J.L. Jiao, C. Chen, Eur. J. Cancer 50, 3230–3242 (2014). 10.1016/j.ejca.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.W. Li, C. Yang, Z. Cheng, Y. Wu, S. Zhou, X. Qi, Y. Zhang, J. Hu, M. Xie, C. Chen, M., 5, e665 (2024). 10.1002/mco2.665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.H. Wang, M. Guo, H. Wei, Y. Chen, Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 8(92 (2023). 10.1038/s41392-023-01347-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.S. Shangary, S. Wang, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. toxicol. 49, 223–241 (2009). 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R.S. Ranaweera, X. Yang, J. Biol. Chem. 288, 18939–18946 (2013). 10.1074/jbc.M113.454470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.P. Ragnhammar, L. Hafstrom, P. Nygren, B., Glimelius and S.B.-g.S.C.o.T.A.i.H. Care, Acta. Oncol. 40, 282–308 (2001). 10.1080/02841860151116367 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.A.M. Gonzalez-Angulo, J. Fuloria, Ochsner J. 4, 163–167 (2002) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.S. Ashique, M. Bhowmick, R. Pal, H. Khatoon, P. Kumar, H. Sharma, A. Garg, S. Kumar, U. Das, Adv. Cancer Biol-Met. 10 (2024). 10.1016/j.adcanc.2024.100114

- 33.Y. Ling, C. Xu, L. Luo, J. Cao, J. Feng, Y. Xue, Q. Zhu, C. Ju, F. Li, Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, X. Ling, J. Med. Chem. 58, 9214–9227 (2015). 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.W. Liu, M. Wang, Z. Guo, Y. He, H. Jia, J. He, S. Miao, Y. Ding, S. Wang, Bioorg. Chem. 133, 106401 (2023). 10.1016/j.bioorg.2023.106401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.S. Kato, J.S. Ross, L. Gay, F. Dayyani, J. Roszik, V. Subbiah, R. Kurzrock, Jco Precis. Oncol. 2018 (2018). 10.1200/PO.17.00235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.J.D. Oliner, A.Y. Saiki, S. Caenepeel, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 6 (2016). 10.1101/cshperspect.a026336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.C.E. Buesoramos, Y. Yang, E. Deleon, P. Mccown, S.A. Stass, M. Albitar, Blood 82, 2617–2623 (1993) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.J.D. Oliner, K.W. Kinzler, P.S. Meltzer, D.L. George, B. Vogelstein, Nature 358, 80–83 (1992). 10.1038/358080a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.C. Poremba, D.W. Yandell, D. Metze, D. Kamanabrou, W. Bocker, B. Dockhorndworniczak, Oncol. Res. 7, 331–339 (1995) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.W. Wang, N. Albadari, Y. Du, J.F. Fowler, H.T. Sang, W. Xian, F. McKeon, W. Li, J. Zhou, R. Zhang, Pharmacol. Rev. 76, 414–453 (2024). 10.1124/pharmrev.123.001026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.R.L. Hayward, J.S. Macpherson, J. Cummings, B.P. Monia, J.F. Smyth, D.I. Jodrell, Mol. Cancer Ther. 3, 169–178 (2004) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.M. Olivier, M. Hollstein, P. Hainaut, Cold. Spring. Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a001008 (2010). 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.C. Glorieux, S. Liu, D. Trachootham, P. Huang, Nat Rev Drug. Discov. 23, 583–606 (2024). 10.1038/s41573-024-00979-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.M. Watanabe, K.D. Moon, M.S. Vacchio, K.S. Hathcock, R.J. Hodes, Immunity 40, 681–691 (2014). 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.A. Banerjee, K. Thyagarajan, S. Chatterjee, P. Chakraborty, P. Kesarwani, M. Soloshchenko, M. Al-Hommrani, K. Andrijauskaite, K. Moxley, H. Janakiraman, M.J. Scheffel, K. Helke, K. Armenson, V. Palanisamy, M.P. Rubinstein, E.G. Mayer, D.J. Cole, C.M. Paulos, J.C. Voelkel, M.I. Nishimura, S. Mehrotra, Cancer Res. 76, 5229–5240 (2016). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.L. Li, D.S. Ng, W.C. Mah, F.F. Almeida, S.A. Rahmat, V.K. Rao, S.C. Leow, F. Laudisi, M.T. Peh, A.M. Goh, J.S. Lim, G.D. Wright, A. Mortellaro, R. Taneja, F. Ginhoux, C.G. Lee, P.K. Moore, D.P. Lane, Cell. Death Differ. 22, 1081–1093 (2015). 10.1038/cdd.2014.212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.G. Guo, M. Yu, W. Xiao, E. Celis, Y. Cui, Cancer Res. 77, 2292–2305 (2017). 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.J. Zhou, I. Kryczek, S. Li, X. Li, A. Aguilar, S. Wei, S. Grove, L. Vatan, J. Yu, Y. Yan, P. Liao, H. Lin, J. Li, G. Li, W. Du, W. Wang, X. Lang, W. Wang, S. Wang, W. Zou, Nat. Immunol. 22, 460–470 (2021). 10.1038/s41590-021-00888-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.