Abstract

Background:

The influence of diet on atherosclerotic progression is not well established, particularly in postmenopausal women, in whom risk factors for progression may differ from those for men.

Objective:

The objective was to investigate associations between dietary macronutrients and progression of coronary atherosclerosis among postmenopausal women.

Design:

Quantitative coronary angiography was performed at baseline and after a mean follow-up of 3.1 y in 2243 coronary segments in 235 postmenopausal women with established coronary heart disease. Usual dietary intake was assessed at baseline.

Results:

The mean (±SD) total fat intake was 25 ± 6% of energy. In multivariate analyses, a higher saturated fat intake was associated with a smaller decline in mean minimal coronary diameter (P = 0.001) and less progression of coronary stenosis (P =0.002) during follow-up. Compared with a 0.22-mm decline in the lowest quartile of intake, there was a 0.10-mm decline in the second quartile (P = 0.002), a 0.07-mm decline in the third quartile (P = 0.002), and no decline in the fourth quartile (P <0.001); P for trend =0.001. This inverse association was more pronounced among women with lower monounsaturated fat (P for interaction =0.04) and higher carbohydrate (P for interaction =0.004) intakes and possibly lower total fat intake (P for interaction =0.09). Carbohydrate intake was positively associated with atherosclerotic progression (P =0.001), particularly when the glycemic index was high. Polyunsaturated fat intake was positively associated with progression when replacing other fats (P = 0.04) but not when replacing carbohydrate or protein. Monoun-saturated and total fat intakes were not associated with progression.

Conclusions:

In postmenopausal women with relatively low total fat intake, a greater saturated fat intake is associated with less progression of coronary atherosclerosis, whereas carbohydrate intake is associated with a greater progression.

Keywords: Diet, saturated fat, carbohydrate, coronary atherosclerosis, women

INTRODUCTION

The optimal dietary pattern to reduce progression of atherosclerosis is not well established. On the basis of ecologic and animal studies, a reduction in the proportion of calories from fat, particularly saturated fat, is generally recommended (1). However, the results of prior studies have been conflicting regarding the relative importance of saturated fat intake on atherosclerotic progression (2, 3). Additionally, if the proportion of energy from saturated fat is reduced, it is uncertain whether replacement with polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, carbohydrate, or protein affects risk differently. High carbohydrate intake, for example, may adversely influence atherosclerotic risk (4–7). These questions are of considerable scientific and public health importance, particularly in light of the current controversy regarding the optimal diet and competing popular diets (4–14). Our understanding of the relations between nutrient intake and coronary heart disease (CHD) risk is also heavily weighted toward observations in men (15, 16), and there may be some differences in these relations in women (15, 17–22). The influence of diet in women may be particularly relevant after menopause, when changes in lipoprotein concentrations—particularly a decrease in HDL cholesterol—may mediate higher CHD risk (23).

We recently reported that modest fish intake was associated with less progression of coronary atherosclerosis among post-menopausal women (24). However, relations between other dietary factors and atherosclerotic progression in postmenopausal women are unknown. We therefore investigated the relations between usual dietary intake of major nutrients, assessed at baseline, and progression of coronary atherosclerosis during a 3-y follow-up of post-menopausal women enrolled in the Estrogen Replacement and Atherosclerosis (ERA) trial, a multicenter clinical trial evaluating the effects of hormone replacement therapy on atherosclerotic progression. We were particularly interested in evaluating the association of saturated fat intake with atherosclerotic progression and in estimating the effect of isocaloric replacement with other nutrients.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study design and population

The ERA trial was a randomized comparison of the effects of hormone replacement (0.625 mg/d oral conjugated estrogen with or without a continuous low dose of 2.5 mg/d progestin as medroxyprogesterone acetate) with those of a placebo on the angiographic progression of coronary atherosclerosis in 309 post-menopausal women with established CHD. The design, recruitment experience, participant characteristics, and primary results were previously described (25, 26). Briefly, 309 post-menopausal women were enrolled in 1995–1996 from 6 US sites: the University of Alabama, Birmingham; Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC; Moses Cone Health System, Greensboro, NC; Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT; Forsyth Memorial Hospital, Winston-Salem, NC; and Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC. Women were eligible if they were postmenopausal, were not currently receiving hormone replacement therapy, and had one or more epicardial coronary stenoses ≥30% of the luminal diameter. Women were excluded if they had known or suspected breast or endometrial carcinoma, previous or planned coronary bypass surgery, history of deep-vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, symptomatic gallstones, a serum aspartate aminotransferase concentration >1.5 times normal, a fasting triacylglycerol concentration >400 mg/dL, a serum creatinine concentration >2.0 mg/dL, left main stenosis >70%, uncontrolled hypertension, or uncontrolled diabetes. Of 815 women screened, 309 (38%) were enrolled. Each center’s institutional review committee approved the study, and all subjects gave informed consent.

At baseline, the participants completed standard questionnaires on health status, medical history, physical activity, dietary intake, and cardiovascular disease risk factors and underwent clinic examination and laboratory testing, including centralized measurement of fasting lipoproteins (25, 26). Diabetes was defined by the combination of self-report and treatment with diabetes medication. We excluded 61 women in whom follow-up coronary angiography was not available (including 12 women who died before follow-up angiography) and 13 women in whom a food-frequency questionnaire was not administered at baseline, resulting in 235 women with 2243 evaluable coronary segments (see below) included in this analysis. Except for less aspirin use among the women not included in this analysis (54% compared with 73%; P =0.003), baseline characteristics of the women who were not included were similar to those who were included.

Dietary assessment

Usual dietary intake was assessed at baseline with a validated, semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire (27–29). Participants were asked to indicate how often, on average, they had consumed given amounts of various specified foods during the past year. Open-ended questions were used for other supplements and foods, including breakfast cereal, multivitamin supplements, margarine, and vegetable oil used for frying or baking. Nutrient intakes were calculated as the frequency of intake multiplied by the nutrient composition of the specified portion size, modified by responses to the open-ended items. The reproducibility and validity of this food-frequency questionnaire were described in detail previously (27–29); for example, the correlation coefficient for saturated fat intake assessed by the questionnaire versus 2 one-week diet records was 0.75.

Coronary angiography

Participants underwent quantitative coronary angiography at baseline and after an average follow-up of 3.1 y. Methods for assessing change in minimal diameter of the major coronary epicardial segments were described previously (25, 26). Measurements were performed by using a previously validated system of cine projectors (SME-3500; Sony, Park Ridge, NJ) and software (QCAPlus; Sanders Data Systems, Palo Alto, CA) by operators unaware of the women’s dietary habits or temporal sequence of the films. With this system, the mean intraoperator difference between blinded duplicate measurements of minimal diameter for vessels with lesions was 0.02 mm (30). The reference, minimal, and average luminal diameters and the degree of stenosis as a percentage of the reference diameter were assessed in 10 proximal epicardial segments (26). From 2350 possible segments, 107 were not analyzed because of total occlusion or intervening coronary bypass surgery, resulting in 2243 segments (χ̄: 9.5 per participant) being analyzed.

Statistical analysis

Nutrient intakes were evaluated as categorical (indicator) variables in quartiles and as continuous variables defined by the proportion of energy obtained from the nutrient. The prespecified primary outcome was the change in mean minimal luminal diameter of the major coronary epicardial segments. Secondary outcomes included the change in stenosis measured as a percentage of the reference diameter and clinical events. Outcomes were assessed by using maximum likelihood random-effects regression models, adjusted for location of the coronary segment, length of follow-up, enrollment site, early coronary angiography due to clinical indications (n = 10), and baseline measurements. This model allows for differential disease progression across different coronary segments and for correlation in segment changes with in a given participant. To minimize potential confounding, the base model was adjusted for covariates likely to be associated with the outcome of interest based on previously published data as well as those variables associated with exposures or outcomes in the current data set. Age, education, diabetes, smoking status, pack-years of smoking, use of lipid-lowering medication, and intakes of carbohydrate, protein, and total energy were included in the final model. Other covariates that did not materially alter the relations between nutrient intakes and angiographic progression and were therefore excluded from the final model included race; hypertension; prior myocardial infarction (MI); prior percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA); systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure; body mass index; waist-hip ratio; physical activity; hormone replacement group; use of aspirin, β-blockers, or angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors; serum lipoproteins; glycated hemoglobin; and intake of alcohol, n−3 fatty acids, trans fatty acids, fiber, fish, and antioxidant vitamins.

As previously described (16), the effect of isocaloric replacement of a nutrient with other nutrients was estimated by using nutrient density models, in which the interpretation of each nutrient’s coefficient is the effect of isocaloric substitution of that nutrient for other nutrients not included in the model. For example, when the model includes total fat, protein, and total energy, the coefficient for total fat estimates the effect of isocaloric replacement of total fat for carbohydrate; when the model includes saturated fat, carbohydrate, protein, and total energy, the coefficient for saturated fat estimates the effect of isocaloric replacement of saturated fat for other fats (monounsaturated or polyunsaturated). Given their correlation (r = 0.83), saturated and monounsaturated fat intakes were not included together in the main adjusted model but were evaluated together in more specific replacement models. Tests for linear trend were calculated by assigning women the median intake in their quartile of nutrient intake and then analyzing this as a continuous variable. Potential effect modification was assessed by using likelihood ratio testing in prespecified analyses for age, diabetes, smoking, and use of lipid-lowering medication and in post hoc analyses for body mass index, hormone replacement, prior MI, prior PTCA, severity of vessel stenosis, and intake of other nutrients. The ERA trial was powered to detect a difference of 0.054 mm in change in mean minimal luminal diameter from baseline to follow-up, driven by high precision (low variance) in the outcome as a result of repeated measures in each subject. Analyses were performed by using STATA 7.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). All P values are two-tailed (α= 0.05).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics overall and according to quartiles of saturated fat intake are shown in Table 1. The average age of the subjects was 66 y at baseline (range: 48–79 y). Approximately one-quarter of the participants had diabetes, three-quarters were overweight, and one-half were obese. In this cohort of women with established CHD, total fat intake was relatively low (x¯ ±SD: 25 ± 6% of energy). Saturated fat intake was positively associated with current smoking and pack-years of smoking and was inversely associated with the use of platelet inhibitors (aspirin or ticlopidine). A higher saturated fat intake was associated with a more favorable lipoprotein profile, including higher HDL, HDL2, and HDL3 cholesterol; higher apoprotein A-I; lower tri- acylglycerol concentrations; and a lower ratio of total cholesterol (TC) to HDL cholesterol (TC:HDL cholesterol). Women who consumed more saturated fat consumed less carbohydrate and dietary fiber and more total fat, protein, cholesterol, polyunsaturated fat, trans fatty acids, and monounsaturated fat.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics according to saturated fat intake1

| Quartile of saturated fat intake (range of intake, % of energy)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (3.5–7.0) (n = 59) | 2 (7.1–8.6) (n = 59) | 3 (8.7–10.5) (n = 59) | 4 (10.6–16.0) (n = 58) | P2 | |

| Age (y) | 65 ± 73 | 67 ± 6 | 67 ± 7 | 65 ± 7 | — |

| Nonwhite race (%) | 15 | 15 | 14 | 17 | — |

| Education > high school (%) | 26 | 22 | 14 | 26 | — |

| Diabetes (%) | 19 | 24 | 20 | 31 | — |

| Smoking (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| Never | 39 | 42 | 34 | 26 | — |

| Former | 53 | 49 | 49 | 40 | — |

| Current | 8 | 8 | 17 | 34 | — |

| Smoking (pack-years) | 18 ± 24 | 16 ± 24 | 15 ± 19 | 34 ± 33 | <0.01 |

| Hypertension (%) | 75 | 66 | 69 | 62 | — |

| Prior MI (%) | 56 | 44 | 42 | 47 | — |

| Prior PTCA (%) | 51 | 44 | 47 | 41 | — |

| Mean blood pressure (mm Hg) | 95 ± 10 | 94 ± 9 | 93 ± 10 | 94 ± 11 | — |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 5 | 29 ± 6 | 30 ± 5 | 30 ± 7 | — |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 0.88 ± 0.09 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 0.86 ± 0.10 | — |

| Physical activity, PASE score | 123 ± 76 | 120 ± 82 | 127 ± 88 | 107 ± 73 | — |

| Hormone replacement (%) | |||||

| Placebo | 37 | 37 | 29 | 33 | — |

| Estrogen only | 29 | 26 | 37 | 34 | — |

| Estrogen + progestin | 34 | 37 | 34 | 33 | — |

| Aspirin or ticlopidine (%) | 81 | 75 | 71 | 66 | <0.05 |

| β-Blockers (%) | 46 | 49 | 51 | 38 | — |

| Lipid-lowering medication (%) | 36 | 42 | 37 | 26 | — |

| ACE inhibitors (%) | 24 | 12 | 27 | 17 | — |

| Total:HDL cholesterol | 5.3 ± 1.5 | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 5.2 ± 1.5 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | <0.01 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 141 ± 44 | 137 ± 39 | 139 ± 40 | 135 ± 39 | — |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 44 ± 9 | 40 ± 12 | 44 ± 9 | 50 ± 14 | <0.01 |

| Triacylglycerols (mg/dL) | 201 ± 73 | 219 ± 93 | 210 ± 88 | 169 ± 77 | <0.05 |

| Lipoprotein(a) (mg/dL) | 32 ± 34 | 39 ± 46 | 32 ± 41 | 36 ± 32 | — |

| HDL2 (mg/dL) | 4.3 ± 4.4 | 4.7 ± 4.6 | 5.2 ± 5.0 | 5.9 ± 4.5 | <0.05 |

| HDL3 (mg/dL) | 40 ± 9 | 36 ± 11 | 39 ± 9 | 44 ± 13 | <0.05 |

| Apoprotein A-I (mg/dL) | 136 ± 21 | 127 ± 28 | 139 ± 19 | 144 ± 27 | <0.05 |

| Apoprotein B (mg/dL) | 120 ± 24 | 116 ± 23 | 117 ± 25 | 111 ± 26 | — |

| 2-h Glucose (mg/dL)4 | 137 ± 44 | 167 ± 74 | 161 ± 63 | 150 ± 67 | — |

| 2-h Insulin (μU/mL)4 | 61 ± 35 | 68 ± 35 | 65 ± 31 | 53 ± 27 | — |

| Total energy (kcal/d) | 1716 ± 578 | 1553 ± 585 | 1708 ± 604 | 1646 ± 609 | — |

| Total fat (% of energy) | 18 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | 27 ± 4 | 32 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| Carbohydrates (% of energy) | 67 ± 7 | 61 ± 5 | 56 ± 5 | 48 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Protein (% of energy) | 16 ± 4 | 17 ± 4 | 17 ± 3 | 18 ± 3 | <0.001 |

| Polyunsaturated fat (% of energy) | 5 ± 2 | 5 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | 6 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| Monounsaturated fat (% of energy) | 7 ± 1 | 9 ± 1 | 11 ± 2 | 13 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| trans Fat (% of energy) | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol (mg/d) | 160 ± 82 | 195 ± 92 | 240 ± 149 | 265 ± 100 | <0.001 |

| n−3 Fatty acids (g/d) | 0.28 ± 0.28 | 0.25 ± 0.27 | 0.23 ± 0.22 | 0.26 ± 0.21 | |

| Alcohol use in past month (%) | 12 | 7 | 14 | 19 | — |

| Dietary fiber (g/d) | 25 ± 14 | 21 ± 10 | 20 ± 8 | 17 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| Time to follow-up (y) | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | — |

MI, myocardial infarction; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; PASE, Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Across quartiles according to tests for linear trend (linear or logistic regression with the characteristic as the dependent variable and quartiles of saturated fat intake as the independent variable; women were assigned in each quartile to the median intake in their quartile).

x¯± SD (all such values)

Oral-glucose-tolerance test among nondiabetic subjects.

Progression of atherosclerosis

Women with higher saturated fat intakes had less progression of coronary atherosclerosis (Table 2). Compared with a 0.15-mm decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter in the lowest quartile of intake, there were 0.08-mm, 0.07-mm, and 0.06-mm declines in the second, third, and fourth quartiles, respectively (P = 0.06, P = 0.02, and P = 0.02 for comparison with the first quartile, respectively; P for trend = 0.02; Table 2). This inverse relation was even more pronounced after adjustment for demographic, clinical, and dietary factors (Table 2, adjusted models). Compared with a 0.22-mm decline in the first quartile, there were 0.10-mm and 0.07-mm declines in the second (P = 0.002) and third (P = 0.002) quartiles and there was no decline (0.01-mm increase) in the fourth quartile (P < 0.001); P for trend = 0.001. Adjustment for carbohydrate and protein intakes (or, equivalently, adjustment for total fat intake) had the largest effect on the adjusted change in mean minimal coronary artery diameter associated with saturated fat intake. Saturated fat intake was also inversely associated with the progression of coronary atherosclerosis measured as the change in mean percentage stenosis (Table 2). Compared with an increase in mean percentage stenosis of 8.0% in the lowest quartile, there was only a 3.6% increase in the second quartile, a 2.7% increase in the third quartile, and no increase in the highest quartile (P = 0.004, P = 0.005, and P = 0.001 for comparison with the first quartile, respectively; P for trend = 0.002; adjusted models). When evaluated continuously, a greater saturated fat intake (for each 5% greater energy intake) was associated with a 0.16-mm lower decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter (95% CI: 0.06, 0.26; P = 0.002) and 5.8 less progression in mean percentage stenosis (95% CI: 2.0, 9.7; P = 0.003) (covariates as in the adjusted model, Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Progression of coronary atherosclerosis according to saturated fat intake1

| Quartile of saturated fat intake (range of intake, % of energy)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (3.5–7.0) | 2 (7.1–8.6) | 3 (8.7–10.5) | 4 (10.6–16.0) | P for trend | |

| Minimal coronary artery diameter (mm) | |||||

| Baseline | 1.86 ± 0.042 | 1.91 ± 0.04 | 1.90 ± 0.04 | 2.02 ± 0.043 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted baseline | 1.93 ± 0.06 | 1.92 ± 0.05 | 1.87 ± 0.04 | 1.95 ± 0.06 | 0.90 |

| Follow-up | 1.71 ± 0.05 | 1.82 ± 0.05 | 1.81 ± 0.05 | 1.95 ± 0.054 | 0.002 |

| Adjusted follow-up | 1.71 ± 0.07 | 1.82 ± 0.05 | 1.79 ± 0.05 | 1.95 ± 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Change | −0.15 ± 0.03 | −0.08 ± 0.03 | −0.07 ± 0.033 | −0.06 ± 0.033 | 0.02 |

| Adjusted change | −0.22 ± 0.04 | −0.10 ± 0.034 | −0.07 ± 0.034 | −0.01 ± 0.045 | 0.001 |

| Coronary artery stenosis (% of reference diameter) | |||||

| Baseline | 30.8 ± 1.1 | 29.5 ± 1.4 | 30.4 ± 1.1 | 28.1 ± 1.4 | 0.14 |

| Adjusted baseline | 29.4 ± 1.6 | 29.0 ± 1.2 | 31.2 ± 1.2 | 29.4 ± 1.7 | 0.85 |

| Follow-up | 36.9 ± 1.6 | 32.9 ± 1.6 | 34.1 ± 1.6 | 30.4 ± 1.64 | 0.01 |

| Adjusted follow-up | 37.4 ± 2.2 | 33.0 ± 1.7 | 34.7 ± 1.6 | 29.7 ± 2.4 | 0.09 |

| Change | 6.0 ± 1.0 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 1.03 | 2.0 ± 1.04 | 0.009 |

| Adjusted change | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 1.14 | 2.7 ± 1.04 | −0.1 ± 1.54 | 0.002 |

All values were estimated by using maximum likelihood random-effects regression models, adjusted for angiographic characteristics, including location of coronary segment, length of follow-up, enrollment site, and early coronary angiography; change also adjusted for baseline angiographic measurements. Adjusted models were further adjusted for age, education (<high school, high school, >high school), diabetes mellitus, smoking status (current, former, and never), pack-years of smoking, use of lipid-lowering medication, carbohydrate intake, protein intake, and total energy intake.

x¯± SE (all such values).

Significantly different from quartile 1: 3 P < 0.05, 4 P < 0.01, 5 P < 0.001.

Further adjustments for other characteristics had little effect on these results. For example, after further adjustment for physical activity, history of MI or PTCA, use of aspirin or angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors, and intakes of n−3 fatty acids, trans fatty acids, alcohol, and dietary fiber, women in the lowest quartile of saturated fat intake had a 0.21-mm decline in minimal coronary artery diameter compared with declines of 0.10 and 0.07 mm and no decline (0.01-mm increase) in the second, third, and fourth quartiles, respectively (P = 0.004, P = 0.003, and P = 0.001 compared with the first quartile, respectively; P for trend = 0.002). Additional adjustment for other covariates (including race, hypertension, blood pressure, body mass index, waist-hip ratio, hormone replacement group, β-blocker use, glycated hemoglobin, intakes of fish and antioxidant vitamins, and changes in smoking habits, antiplatelet medication use, and lipid-lowering medication use from baseline to follow-up (data not shown) had similarly little effect.

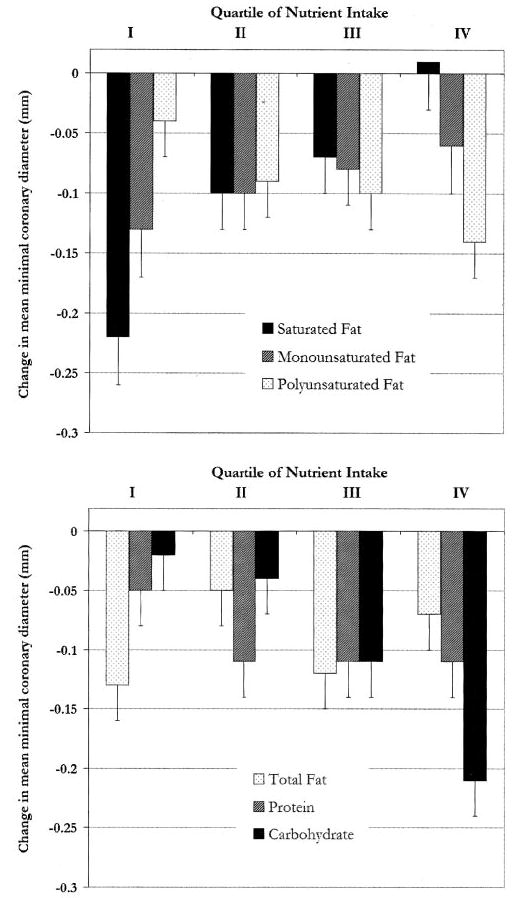

Other nutrients

We also evaluated the relations of other major dietary nutrients with atherosclerotic progression (Figure 1). Polyunsaturated fat intake was positively associated with a decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter (P for trend = 0.04). Carbohydrate intake was strongly positively associated with progression, with a 19-mm greater decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter in a comparison of extreme quartiles of intake (P for trend = 0.001). Mono-unsaturated fat, total fat, and protein intakes were not associated with progression, although the detection of a possible inverse relation between monounsaturated fat intake and atherosclerotic progression may have been limited by slightly larger SEEs. When evaluated continuously, a greater polyunsaturated fat intake (for each 5% greater energy intake) was associated with a 0.17-mm greater decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter (95%CI:0.08,0.26; P < 0.001) and a 5.8 greater progression in mean percentage stenosis (95% CI: 2.3, 9.3; P = 0.001), whereas a greater carbohydrate intake (for each 10% greater energy intake) was associated with a 0.07-mm greater decline in mean minimal coronary artery diameter (95% CI: 0.02, 0.12; P = 0.003) and a 2.8 greater progression in mean percentage stenosis (95% CI: 0.9, 4.6; P = 0.003) (adjustments as in Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Mean (±SE) change in minimal coronary artery diameter according to intake of different nutrients, with adjustments as in Table 2 (see footnote 1), except that total fat was not adjusted for carbohydrate, and carbohydrate and protein were also adjusted for polyunsaturated fat. These models estimate the effect of saturated fat replacing other fats (monounsaturated or polyunsaturated), monounsaturated fat replacing other fats (saturated or polyunsaturated), polyunsaturated fat replacing other fats (saturated or monounsaturated), total fat replacing carbohydrate, carbohydrate replacing saturated or monounsaturated fat, and protein replacing saturated or monounsaturated fat. Median intakes (% of energy) for quartiles 1-4 were as follows: saturated fat (6.1, 7.8, 9.5, and 12.0), monounsaturated fat (6.9, 8.6, 10.7, and 13.0), polyunsaturated fat (3.9, 5.2, 6.1, and 7.5), total fat (17.6, 21.7, 27.0, and 31.9), carbohydrate (47.1, 55.6, 60.5, and 68.9), and protein (12.7, 15.8, 18.0, and 21.2). P for trend = 0.001 (saturated fat), 0.40 (monounsaturated fat), 0.04 (polyunsaturated fat), 0.48 (total fat), 0.20 (protein), and 0.001 (carbohydrate).

Other replacement models

The models in Table 2 and Figure 1 can be interpreted as estimating the effect of a greater intake of saturated fat replacing other fats (polyunsaturated or monounsaturated), monounsaturated fat replacing other fats (saturated or polyunsaturated), poly-unsaturated fat replacing other fats (saturated or monounsaturated), total fat replacing carbohydrate, carbohydrate replacing saturated or monounsaturated fat, and protein replacing saturated or monounsaturated fat. We evaluated other potential relations of interest (Table 3). Carbohydrate intake was associated with greater atherosclerotic progression when replacing saturated fat (P = 0.04) and with a trend toward greater atherosclerotic progression when replacing monounsaturated fat (P = 0.09). Poly-unsaturated fat intake was associated with greater atherosclerotic progression when replacing saturated fat (P = 0.02).

TABLE 3.

Estimated effect of isocaloric substitution of nutrients on progression of coronary atherosclerosis1

| Greater intake of

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In place of | Monounsaturated fat | Polyunsaturated fat | Carbohydrate | Protein |

| Saturated fat | 0.07 (−0.08, 0.22) | −0.11 (−0.20 to −0.01)2 | −0.18 (−0.35 to −0.01)2 | 0.00 (−0.13 to 0.12) |

| Monounsaturated fat | −0.04 (−0.14 to 0.07) | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.03)3 | 0.01 (−0.11 to 0.12) | |

| Polyunsaturated fat | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.14) | 0.07 (−0.05 to 0.20) | ||

| Total fat | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05) | 0.00 (−0.10 to 0.09) | ||

| Carbohydrate | 0.00 (−0.08 to 0.08) | |||

Values are the differences (and 95% CIs) in change in mean minimal coronary artery diameter after a comparison of extreme quartiles of intake (negative numbers represent greater progression). The models include the covariates given in Table 2 plus all (mutually exclusive) nutrients except the replacement nutrient (see Subjects and Methods for details). For example, the effect of replacing nutrient A with B was estimated by including all nutrients except B; conversely, the effect of replacing B with A was estimated by including all nutrients except A. These paired models were consistent (one estimate was approximately the inverse of the other) except for 2 pairs—saturated fat and monounsaturated fat and saturated fat and protein—in which there was less progression when saturated fat replaced monounsaturated fat (P = 0.04) or protein (P = 0.02), but there was no significant difference when monounsaturated fat (P = 0.38) or protein (P = 0.58) replaced saturated fat. For these 2 pairs, the conservative (NS) latter results are presented.

P < 0.05 (comparison of extreme quartiles).

P < 0.10 (comparison of extreme quartiles).

Interaction by nutrients and risk factors

Greater saturated fat intake was significantly or nearly significantly associated with less progression of coronary atherosclerosis among a variety of risk factor and nutrient intake subgroups (Table 4). This association was more pronounced among women consuming less monounsaturated fat (P for interaction = 0.04) and possibly less total fat (P for interaction = 0.09). The association was significant for carbohydrate intake dichotomized at median intake (P for interaction = 0.004). Additionally, among the women not taking lipid-lowering medication at baseline or during follow-up, there was 0.22 mm less progression for each 5% greater energy intake from saturated fat, compared with 0.09 mm less progression for each 5% greater energy intake from saturated fat among women taking lipid-lowering medication (P for interaction = 0.008). The inverse association between saturated fat intake and progression was not statistically different by a variety of other dietary and risk factors (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Progression of coronary atherosclerosis in women according to saturated fat intake, by dietary nutrient and risk factor subgroups1

| Difference in change (95% CI)2 | P for interaction3 | |

|---|---|---|

| Dietary nutrient (% of energy) | mm | |

| Total fat | ||

| ≤20 (n = 62) | 0.21 (0.01, 0.42) | |

| 21–29 (n = 125) | 0.17 (0.03 to 0.30) | 0.09 |

| ≥30 (n = 48) | 0.11 (−0.04 to 0.26) | |

| Carbohydrate | ||

| <58.7 (n = 118) | 0.11 (0.01 to 0.21) | 0.004 |

| ≥58.7 (n = 117) | 0.31 (0.17 to 0.45) | |

| Protein | ||

| <16.7 (n = 118) | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.35) | 0.45 |

| ≥16.7 (n = 117) | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.22) | |

| Polyunsaturated fat | ||

| <5.6 (n = 118) | 0.17 (0.05 to 0.29) | 0.76 |

| ≥5.6 (n = 117) | 0.14 (0.02 to 0.25) | |

| Monounsaturated fat | ||

| < 9.7 (n = 118) | 0.24 (0.11 to 0.38) | 0.04 |

| ≥9.7 (n = 117) | 0.11 (0.00 to 0.22) | |

| Glycemic index | ||

| < 55.1 (n = 118) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | 0.11 |

| ≥55.1 (n = 117) | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.31) | |

| Risk factor | ||

| Age (y) | ||

| ≤66 (n = 116) | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.24) | 0.27 |

| >66 (n = 119) | 0.19 (0.08 to 0.30) | |

| BMI (kg/m2)4 | ||

| <25 (n = 58) | 0.15 (0.01 to 0.28) | |

| 25–30 (n = 75) | 0.20 (0.07 to 0.34) | 0.76 |

| >30 (n = 97) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | |

| Diabetes | ||

| No (n = 180) | 0.14 (0.04 to 0.24) | 0.22 |

| Yes (n = 55) | 0.21 (0.08 to 0.34) | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never (n = 83) | 0.21 (0.09 to 0.33) | |

| Former (n = 112) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.26) | 0.25 |

| Current (n = 40) | 0.10 (−0.04 to 0.24) | |

| Lipid-lowering medication | ||

| No (n = 103) | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33) | 0.008 |

| Yes (n = 132) | 0.09 (−0.02 to 0.20) | |

| Hormone replacement therapy | ||

| None (n = 80) | 0.20 (0.08 to 0.32) | |

| Estrogen (n = 74) | 0.12 (0.00 to 0.24) | 0.42 |

| Estrogen + progestin (n = 81) | 0.16 (0.04 to 0.27) | |

| Prior MI | ||

| No (n = 124) | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.25) | 0.36 |

| Yes (n = 111) | 0.18 (0.07 to 0.29) | |

| Prior PTCA | ||

| No (n = 127) | 0.15 (0.04 to 0.25) | 0.75 |

| Yes (n = 108) | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.27) | |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)4 | ||

| <138 (n = 109) | 0.16 (0.05 to 0.27) | 0.88 |

| ≥138 (n = 109) | 0.15 (0.02 to 0.28) | |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)4 | ||

| <44 (n = 118) | 0.13 (0.01 to 0.25) | 0.72 |

| ≥44 (n = 114) | 0.17 (0.06 to 0.28) | |

| Vessels with ≥30% stenosis5 | ||

| No | 0.17 (0.07 to 0.28) | 0.41 |

| Yes | 0.14 (0.04 to 0.25) | |

| Time to follow-up (y) | ||

| <3.3 (n = 118) | 0.16 (0.06 to 0.26) | 0.18 |

| ≥3.3 (n = 117) | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.25) | |

MI, myocardial infarction; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty.

The difference in change in mean minimal coronary artery diameter associated with greater saturated fat intake (for each 5% greater energy intake); positive numbers represent less progression (covariates as in Table 2).

Log-likelihoodratiotest,withcontinuousinteractiontermsforcontinuous covariates, except for carbohydrate, which was evaluated as a binary variable dichotomized at median intake.

Not all women were included because of missing values.

There were a total of 1269 segments in 231 women with <30% stenosis and 951 segments in 227 women with ≥30% stenosis.

In similar analyses (data not shown), the positive association between polyunsaturated fat intake and atherosclerotic progression was more pronounced among women with diabetes (P for interaction = 0.001), lower HDL cholesterol (P for interaction = 0.007), a lower protein intake (P for interaction = 0.006), and a higher glycemic index (P for interaction = 0.02) (adjustments as in Figure 1). The positive association between carbohydrate intake and atherosclerotic progression was perhaps more pronounced among women with less physical activity (P for interaction = 0.07); furthermore, a higher carbohydrate intake (for each 10% greater energy intake) was associated with a 0.14-mm greater decline (95% CI: 0.07, 0.20; P < 0.001) in mean minimal coronary artery diameter in analyses restricted to women with a higher glycemic index (≥55.1) but was not associated with change in mean minimal coronary artery diameter (0.01-mm increase; 95% CI: −0.08, 0.05; P = 0.73) in analyses restricted to women with a glycemic index lower than the median (<55.1) (adjustments as in Figure 1).

Potential mediators

Effects of dietary macronutrients on atherosclerosis may be in part mediated by effects on body mass index, insulin sensitivity, or serum lipids. We therefore evaluated the extent to which differences in these factors—both at baseline and follow-up—might mediate the observed associations. Additional adjustment for baseline body mass index, 2-h glucose, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triacylglycerols (other covariates as in Table 2 and Figure 1) did not greatly alter the change in mean minimal coronary artery diameter associated with intake of saturated fat (0.15 mm less progression per every 5% greater energy intake from saturated fat: 95% CI: 0.04, 0.26; P = 0.006), poly-unsaturated fat (0.17 mm greater progression per every 5% greater energy intake from polyunsaturated fat: 95% CI: 0.08, 0.27; P < 0.001), or carbohydrate (0.07 mm greater progression per every 10% greater energy intake from carbohydrate: 95% CI: 0.02, 0.13; P = 0.007). Changes in body mass index, glucose, or serum lipids at follow-up also did not appear to mediate the observed associations; of note, differences in lipids according to categories of nutrient intake remained relatively constant from baseline to follow-up, which suggested that relative rankings of nutrient intakes were consistent over time (data not shown).

Specific saturated fatty acids

We also separately evaluated relations of stearic acid (18:0) (25% of saturated fat intake) compared with lauric (12:0), myristic (14:0), and palmitic (16:0) acids (67% of saturated fat intake) with angiographic progression. After adjustments (as in Table 2 footnote), each 1% greater energy intake from stearic acid was associated with 0.11 mm less of a decline in minimal coronary artery diameter (95% CI: 0.03, 0.18; P = 0.004), whereas each 1% greater energy intake from lauric, myristic, or palmitic acid was associated with 0.05 mm less of a decline in minimal coronary artery diameter (95% CI: 0.02, 0.08; P = 0.001).

Clinical outcomes

We also evaluated associations of saturated fat intake with clinical events. After adjustment for other risk factors (as in Table 2 footnote), greater intake of saturated fat (for each 5% greater energy intake) was not associated with coronary revascularization [odds ratio (OR): 0.64; 95% CI: 0.1, 6.1; n = 55), unstable angina (OR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.2, 3.3; n = 47), or MI or CHD death (OR: 0.83; 95% CI: 0.2, 3.3; n = 18), although there was low power to detect these potential associations.

DISCUSSION

Among postmenopausal women with established CHD, greater saturated fat intake was associated with less progression of coronary atherosclerosis over an average follow-up of 3 y, whereas polyunsaturated fat and carbohydrate intakes were associated with greater progression. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the associations between dietary macronutrients and atherosclerotic progression in women. Although the findings do not establish causality, the associations were independent of a variety of other risk factors, including age, diabetes, smoking, body mass index, physical activity, prior MI or PTCA, and other dietary habits. Thus, known clinical risk factors do not appear to account for the observed relations.

The inverse association between saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic progression was unexpected. However, this finding should perhaps be less surprising. Ecologic and animal experimental studies showed positive relations between saturated fat intake and CHD risk (8). However, cohort studies and clinical trials in humans have been far less consistent (9–12). Furthermore, most studies of dietary fat and CHD risk have been performed in men (15, 16). The relations in women—particularly postmenopausal women—are much less well-established, and evidence from dietary intervention trials suggests that diets low in saturated fat may have different effects on CHD risk factors in women (15, 17–22).

Women were excluded from prior studies evaluating nutrient intake and atherosclerotic progression (2, 3, 31). In the only large cohort study to focus on relations between dietary fat and CHD events in women, saturated fat intake was positively associated with CHD risk, but this association was attenuated and no longer significant after adjustment for intakes of polyunsaturated fat and other nutrients (16). The absence of an inverse association in that study may have been due to different study populations (generally healthy pre- and postmenopausal women compared with postmenopausal women with established CHD), outcomes (incident CHD events compared with atherosclerotic progression), or background diets (eg, mean total fat intake of 38% compared with 25%). In a prospective study of 661 diabetic persons, saturated fat intake was inversely (P = 0.007) and carbohydrate intake was positively (P = 0.002) associated with incident MI in women but not in men (22); however, the analyses were not adjusted for other risk factors. Of 15 trials that included dietary intervention for primary or secondary prevention of CHD (32–46), 10 excluded women and 3 included only ≈10% women and did not report results by sex (Table 5). Even among trials comprised exclusively or largely of men, diets low in saturated fat have not consistently reduced CHD risk (32–39), especially when compared with diets focusing on fish, α-linolenic acid, fruit, vegetables, nuts, and monounsaturated fat (40, 43–46). Thus, there is a relative paucity of literature on dietary fat and CHD risk in women, particularly postmenopausal women.

TABLE 5.

Clinical trials including dietary intervention for primary or secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (CHD)1

| Trial | Population | Intervention | Outcome | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Committee, 1965 (33) | 264 men post-MI | ↓Total fat | MI and fatal CHD ↑1% | NS |

| Medical Research Council, 1968 (34) | 393 men post-MI | ↑ALA, ↓ saturated fat | MI and fatal CHD ↓18% | NS |

| Oslo Diet-Heart, 1970 (35) | 412 men post-MI | ↑P:S | CHD mortality ↓16% | 0.10 |

| Sydney Diet-Heart, 1978 | 458 men post-MI | ↑P:S | Total mortality ↑42% | < 0.01 |

| (36) | ||||

| Los Angeles Veterans, 1968 (37) | 846 men | ↑P:S | MI and sudden death ↓33% | NS |

| Oslo Study Group, 1981 (38) | 1232 men | ↓Total fat, ↓saturated fat; ↑fiber2 | MI and fatal CHD ↓46% | 0.03 |

| European Collaborative Group, 1986 (39) | 60 881 men | ↓Total fat, ↓saturated fat3 | MI and fatal CHD ↓10% | 0.07 |

| MRFIT, 1990 (40) | 12 866 men | ↓Total fat, ↑P:S4 | CHD mortality ↓11% | NS |

| Finnish Mental Hospital, 1979 (41) | 461 men | ↑↑ALA, ↑P:S | ECG change and CHD death ↓68% | 0.03 |

| Finnish Mental Hospital, 1983 (42) | 591 women | ↑↑ALA, ↑P:S | ECG change and CHD death ↓60% | 0.10 |

| Minnesota Coronary Survey, 1989 (43) | 4664 women, 4393 men | ↑P:S | MI and sudden death ↑6% | NS |

| DART, 1989 (44)5 | 2033 men post-MI | Cereal fiber | CHD death ↑27% | NS |

| DART, 1989 (44)5 | 2033 men post-MI | Fatty fish | CHD death ↓32% | < 0.01 |

| Singh et al, 1992 (45) | 505 men post-MI | Nuts, fruit, and vegetables, whole grains | MI and sudden death ↓40% | < 0.001 |

| Lyon Diet-Heart, 1994 (46) | 61 women, 544 men post-MI | Canola oil, legumes, fruit and vegetables, fish | MI and CHD death ↓73% | 0.001 |

| Indo-Mediterranean Diet- Heart, 2002 (47) | 103 women, 897 men | Nuts, fruit and vegetables, whole grains | MI and sudden death ↓52% | < 0.001 |

MRFIT, Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial; DART, Diet and Reinfarction Trial; MI, myocardial infarction; P:S, ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fatty acids; ECG, electrocardiogram; ALA, α-linolenic acid.

Intervention group also received advice on smoking cessation.

Intervention group also received advice on smoking cessation, blood pressure control, weight control, and exercise.

Intervention group also received advice on smoking cessation and drug treatment to control hypertension.

2 × 2 factorial design.

The magnitude, independence, and consistency of the inverse association between saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic progression are notable. Are there plausible biologic mechanisms for such an effect? In contrast with the findings of experimental studies (20, 21, 47–50), saturated fat intake was not associated with LDL concentrations in our study. Women with lower saturated fat intake at enrollment may have previously had higher LDL-cholesterol concentrations and thus lowered their saturated fat intake. If so, they were successful in lowering their LDL cholesterol to concentrations similar to those of other women in this cohort; however, even at similar LDL-cholesterol concentrations, their rate of atherosclerotic progression was much higher, which indicates that factors besides LDL are important in determining atherosclerotic progression in postmenopausal women. A greater saturated fat intake was associated with other lipid differences, including higher HDL, higher HDL2, higher apoprotein A-I, lower triacylglycerol concentrations, and a lower TC:HDL cholesterol ratio. These findings are consistent with those of experimental studies that showed unfavorable effects of low-fat, low-saturated-fat diets on HDL cholesterol, HDL2 cholesterol, the TC:HDL cholesterol ratio, and postprandial triacyl-glycerol concentrations in women (18, 20, 21, 47–51), particularly when compared with men (18, 20–21). For example, among hypercholesterolemic subjects treated with a National Cholesterol Education Program Step II diet (< 30% fat, < 7% saturated fat), HDL decreased 1.3% in men and 7.6% in women (P < 0.001 for sex difference), HDL2 increased 0.5% in men and decreased 16.7% in women (P < 0.001), apoprotein A-I was unchanged in men but decreased 5.3% in women (P < 0.001), and the TC:HDL cholesterol ratio decreased 3% in men and increased 3% in women (P < 0.01) (20).

Although LDL cholesterol strongly predicts CHD risk in men, these non-LDL lipid variables are stronger predictors in women (19, 23, 52, 53). Effects of saturated fat intake on HDL and triacylglycerols may be especially important after menopause, when HDL-cholesterol concentrations are lower and CHD risk is correspondingly greater (23). In our study, the inverse association between saturated fat intake and atherosclerotic progression was greater among women not taking lipid-lowering medication; if saturated fat intake reduces CHD risk via lipoprotein effects, such an influence may be less pronounced when lipids are more potently affected by lipid-lowering medication. This relation was also less pronounced among women with higher monounsaturated fat intake, which has similar favorable effects on HDL and triacylglycerols (4, 6). Thus, these results are consistent with potential biologic effects of saturated and monounsaturated fat intakes in postmenopausal women. However, lipid concentrations at baseline and follow-up did not appear to mediate the observed relations, which suggests either mediation by non-lipid effects of these nutrients or that single baseline and follow-up fasting lipid panels do not adequately capture effects on serum lipids.

Carbohydrate intake was positively associated with atherosclerotic progression when replacing saturated fat and monounsaturated fat but not when replacing total fat, polyunsaturated fat, or protein. The association was perhaps stronger among women with lower physical activity, who would be more susceptible to adverse effects of carbohydrates—particularly refined carbohydrate—on HDL cholesterol, triacylglycerols, glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and weight gain (4–7). Consistent with such biologic mechanisms, the relation between carbohydrate intake and atherosclerotic progression appeared to be stronger in women with a higher glycemic index.

Polyunsaturated fat intake was not associated with atherosclerotic progression when replacing carbohydrate or protein but was positively associated when replacing other fats, especially saturated fat. Few prior studies have evaluated relations between polyunsaturated fat intake and CHD risk in women; those that have been conducted have had conflicting results. In one observational study in women, polyunsaturated fat intake was inversely associated with incident CHD (16). However, in a cohort of diabetic persons, a higher ratio of polyunsaturated to saturated fat (P:S) predicted lower CHD risk in men but not in women (22). Among 591 institutionalized women, a higher P:S diet nonsignificantly lowered CHD risk by 60% (P = 0.10), but the intervention diet also included much higher (by 500%) amounts of n−3 α-linolenic acid (41). A higher P:S causes a greater decline in HDL in women than in men (18). In a clinical trial of 4393 men and 4664 women, a higher-P:S diet did not affect risk in men and women combined, but there were nonsignificant trends toward 32% more CHD events (P = 0.16) and 16% higher total mortality (P = 0.29) in women (42). The positive association seen in our study was more pronounced in diabetic women and in those with a lower HDL cholesterol, a lower protein intake, and a higher glycemic index; confirmation of these results in other studies is indicated.

Our study has several strengths. Outcomes were prospectively ascertained, which reduced the potential for recall bias. A variety of participant characteristics were assessed by using standardized methods, which increased the capacity to adjust for confounding. Angiographic outcomes were centrally evaluated by operators using validated methods who were unaware of the participants’ dietary habits or the temporal sequence of films, which minimized the potential for misclassified or biased outcome measures. The precision in the outcome due to repeated measures provided ample power to detect differences in change in mean minimal luminal diameter from baseline to follow-up.

There were also potential limitations to our findings. Usual dietary intake was assessed at baseline, and there may have been changes in diet over time. Nutrient intakes were estimated from a variety of food items, which limited precise estimation (though relative intakes were probably ranked correctly at the extremes). Without apparent bias, dietary changes over time and measurement errors would attenuate findings toward the null; however, such errors would not cause a harmful association to appear beneficial. Relations of saturated fat intake with atherosclerotic progression may be different among women in whom follow-up coronary angiography is not available; however, the baseline characteristics of these women were generally similar to those included in the analysis, and only 12 women (4%) died before follow-up angiography. We could not assess the relations of nutrient intake with other factors related to CHD risk, such as platelet aggregation or thrombosis; on the other hand, progression of atherosclerosis predicts clinical events (54). Residual confounding by incompletely measured or unknown factors cannot be excluded. This was a post hoc analysis among participants in a randomized trial, and our findings may not be generalizable to all postmenopausal women.

Although CHD is the leading cause of death among both men and women, prior studies have historically focused on relations between risk factors and CHD in men. Our findings are not consistent with the hypothesis—based largely on observations in men—that saturated fat intake increases atherosclerotic progression in postmenopausal women but instead suggest that saturated fat intake may reduce such progression, especially when mono-unsaturated fat intake is low or carbohydrate intake is high. Our findings also suggest that carbohydrate intake may increase atherosclerotic progression, especially when refined carbohydrates replace saturated or monounsaturated fats. Confirmation of these findings in other studies and examination of potential mechanisms and alternative explanations are warranted.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful for the helpful criticisms and insightful comments of Alice Lichtenstein and Arja Erkkilä during the preparation of this manuscript.

All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final submitted manuscript. DH contributed to the acquisition of funding and the data collection. DM contributed to the conception and design of the study. None of the authors had a conflict of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

From the Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and the Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston (DM and EBR); the Health Services Research and Development Program, Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle (DM); the Cardiovascular Nutrition Laboratory, Jean Mayer US Department of Agriculture Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston (AHL and ATE); and the Section on Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, and the Department of Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, NC (DMH).

Supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01 HL-45488) and the National Center for Research Resources General Clinical Research Center (M01 RR07122). Support for DM was provided in part by a Health Services Research & Development fellowship at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System and by an NRSA Training Grant in Academic Nutrition (DK07703) at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Address reprint requests to D Mozaffarian, 665 Huntington Avenue, Building 2, Room 315, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: dmozaffa@hsph.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, et al. American Heart Association’s Dietary Guidelines: revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2000;102:2284–99. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.18.2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watts GF, Jackson P, Mandalia S, et al. Nutrient intake and progression of coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:328–32. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blankenhorn DH, Johnson RL, Mack WJ, el Zein HA, Vailas LI. The influence of diet on the appearance of new lesions in human coronary arteries. JAMA. 1990;263:1646–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katan MB, Grundy SM, Willett WC. Should a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet be recommended for everyone? Beyond low-fat diets. N Engl J Med 1997;337:563–6 (discussion 566–7). [PubMed]

- 5.Liu S, Manson JE. Dietary carbohydrates, physical inactivity, obesity, and the ‘metabolic syndrome’ as predictors of coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grundy SM, Abate N, Chandalia M. Diet composition and the metabolic syndrome: what is the optimal fat intake? Am J Med. 2002;113:25S–9S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00988-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira MA, Liu S. Types of carbohydrates and risk of cardiovascular disease. J Womens Health. 2003;12:115–22. doi: 10.1089/154099903321576501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Connor WE, Connor SL. Should a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet be recommended for everyone? The case for a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. N Engl J Med 1997;337:562–3 (discussion 566–7). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Corr LA, Oliver MF. The low fat/low cholesterol diet is ineffective. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:18–22. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golomb BA. Dietary fats and heart disease—dogma challenged? J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:461–4. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taubes G. Nutrition. The soft science of dietary fat. Science. 2001;291:2536–45. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5513.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ravnskov U, Allen C, Atrens D, et al. Studies of dietary fat and heart disease. Science. 2002;295:1464–5. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1464c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson JW, Konz EC, Jenkins DJ. Health advantages and disadvantages of weight-reducing diets: a computer analysis and critical review. J Am Coll Nutr. 2000;19:578–90. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2000.10718955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crouse JR., III Gender, lipoproteins, diet, and cardiovascular risk. Sauce for the goose may not be sauce for the gander. Lancet. 1989;1:318–20. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, et al. Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1491–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711203372102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LaRosa JC. Lipids and cardiovascular disease: do the findings and therapy apply equally to men and women? Womens Health Issues. 1992;2:102–11. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(05)80278-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cobb M, Greenspan J, Timmons M, Teitelbaum H. Gender differences in lipoprotein responses to diet. Ann Nutr Metab. 1993;37:225–36. doi: 10.1159/000177772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bass KM, Newschaffer CJ, Klag MJ, Bush TL. Plasma lipoprotein levels as predictors of cardiovascular death in women. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2209–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walden CE, Retzlaff BM, Buck BL, Wallick S, McCann BS, Knopp RH. Differential effect of National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Step II diet on HDL cholesterol, its subfractions, and apoprotein A-I levels in hypercholesterolemic women and men after 1 year: the beFIT Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1580–7. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.6.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z, Otvos JD, Lamon-Fava S, et al. Men and women differ in lipoprotein response to dietary saturated fat and cholesterol restriction. J Nutr. 2003;133:3428–33. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soinio M, Laakso M, Lehto S, Hakala P, Ronnemaa T. Dietary fat predicts coronary heart disease events in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:619–24. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bittner V. Lipoprotein abnormalities related to women’s health. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:77I–84I. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erkkilä AT, Lichtenstein AH, Mozaffarian D, Herrington DM. Fish intake is associated with reduced progression of coronaryartery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal women with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Klein KP, et al. The estrogen replacement and atherosclerosis (ERA) study: study design and baseline characteristics of the cohort. Control Clin Trials. 2000;21:257–85. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herrington DM, Reboussin DM, Brosnihan KB, et al. Effects of estrogen replacement on the progression of coronaryartery atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:522–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008243430801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:1114–26. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garland M, Sacks FM, Colditz GA, et al. The relation between dietary intake and adipose tissue composition of selected fatty acids in US women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:25–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willett W, Stampfer M, Chu NF, Spiegelman D, Holmes M, Rimm E. Assessment of questionnaire validity for measuring total fat intake using plasma lipid levels as criteria. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:1107–12. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung WH, Sanders W, Alderman EL. Coronary artery quantitation and data management system for paired cineangiograms. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1991;24:121–34. doi: 10.1002/ccd.1810240211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arntzenius AC, Kromhout D, Barth JD, et al. Diet, lipoproteins, and the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. The Leiden Intervention Trial. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:805–11. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198503283121301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Research Committee. Low-fat diet in myocardial infarction: a controlled trial. Lancet. 1965;2:501–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Report of a Research Committee to the Medical Research Council. Controlled trial of soyabean oil in myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1968;2:693–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leren P. The Oslo Diet-Heart Study. Eleven-year report. Circulation. 1970;42:935–42. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.42.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woodhill JM, Palmer AJ, Leelarthaepin B, McGilchrist C, Blacket RB. Low fat, low cholesterol diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1978;109:317–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-0967-3_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dayton S, Pearce ML, Goldman H, et al. Controlled trial of a diet high in unsaturated fat for prevention of atherosclerotic complications. Lancet. 1968;2:1060–2. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91531-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hjermann I, Velve Byre K, Holme I, Leren P. Effect of diet and smoking intervention on the incidence of coronary heart disease. Report from the Oslo Study Group of a randomised trial in healthy men. Lancet. 1981;2:1303–10. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)91338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organisation European Collaborative Group. European collaborative trial of multifactorial prevention of coronary heart disease: final report on the 6-year results. Lancet. 1986;1:869–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Mortality rates after 10.5 years for participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1990;263:1795–801. doi: 10.1001/jama.1990.03440130083030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Turpeinen O, Karvonen MJ, Pekkarinen M, Miettinen M, Elosuo R, Paavilainen E. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease: the Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1979;8:99–118. doi: 10.1093/ije/8.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miettinen M, Turpeinen O, Karvonen MJ, Pekkarinen M, Paavilainen E, Elosuo R. Dietary prevention of coronary heart disease in women: the Finnish Mental Hospital Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1983;12:17–25. doi: 10.1093/ije/12.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Frantz ID, Jr, Dawson EA, Ashman PL, et al. Test of effect of lipid lowering by diet on cardiovascular risk. The Minnesota Coronary Survey Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:129–35. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, et al. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial (DART) Lancet. 1989;2:757–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90828-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singh RB, Rastogi SS, Verma R, et al. Randomised controlled trial of cardioprotective diet in patients with recent acute myocardial infarction: results of one year follow up. BMJ. 1992;304:1015–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6833.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Mamelle N, et al. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1994;343:1454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92580-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh RB, Dubnov G, Niaz MA, et al. Effect of an Indo-Mediterranean diet on progression of coronary artery disease in high risk patients (Indo-Mediterranean Diet Heart Study): a randomised single-blind trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1455–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11472-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lichtenstein AH, Ausman JM, Jalbert SM, et al. Efficacy of a Therapeutic Lifestyle Change/Step 2 diet in moderately hypercholesterolemic middle aged and elderly female and male subjects. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:264–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lichtenstein AH, Ausman LA, Jalbert S, Schaefer EJ. Effects of different forms of dietary hydrogenated fats on serum lipoprotein cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1933–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geil PB, Anderson JW, Gustafson NJ. Women and men with hypercholesterolemia respond similarly to an American Heart Association step 1 diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 1995;95:436–41. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(95)00118-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ginsberg HN, Kris-Etherton P, Dennis B, et al. Effects of reducing dietary saturated fatty acids on plasma lipids and lipoproteins in healthy subjects: the DELTA Study, protocol 1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:441–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.3.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kuusi T, Ehnholm C, Huttunen JK, et al. Concentration and composition of serum lipoproteins during a low-fat diet at two levels of polyunsaturated fat. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:360–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hong MK, Romm PA, Reagan K, Green CE, Rackley CE. Usefulness of the total cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio in predicting angiographic coronary artery disease in women. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1646–50. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90323-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Walldius G, Jungner I, Holme I, Aastveit AH, Kolar W, Steiner E. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358:2026–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)07098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Azen SP, Mack WJ, Cashin-Hemphill L, et al. Progression of coronary artery disease predicts clinical coronary events. Long-term follow-up from the Cholesterol Lowering Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 1996;93:34–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]