Abstract

In experimental meningitis a single dose of gentamicin (10 mg/kg of body weight) led to gentamicin levels in around cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of 4 mg/liter for 4 h, decreasing slowly to 2 mg/liter 4 h later. The CSF penetration of gentamicin ranged around 27%, calculated by comparison of areas under the curve (AUC in serum/AUC in CSF). Gentamicin monotherapy (−1.24 log10 CFU/ml) was inferior to vancomycin monotherapy (−2.54 log10 CFU/ml) over 8 h against penicillin-resistant pneumococci. However, the combination of vancomycin with gentamicin was significantly superior (−4.48 log10 CFU/ml) compared to either monotherapy alone. The synergistic activity of vancomycin combined with gentamicin was also demonstrated in vitro in time-kill assays.

The treatment of pneumococcal infections has been complicated by the worldwide spread of penicillin-resistant strains (3). In life-threatening infections, particularly in meningitis, penicillin is ineffective even against strains with intermediate resistance, and penicillin resistance is often associated with resistance to other β-lactam antibiotics. Because of treatment failures observed with cephalosporin monotherapy (4, 14), a combination of vancomycin with a broad-spectrum cephalosporin (ceftriaxone or cefotaxime) is usually recommended for treatment of meningitis with resistant strains (12).

However, in case of β-lactam allergy, the choice of an adequate therapy is more challenging. Little is known about the role of gentamicin in meningitis due to penicillin-resistant pneumococci. The aim of this study was to test gentamicin as monotherapy and in combination with vancomycin against penicillin-resistant strains in experimental meningitis. The standard treatment consisted of vancomycin combined with ceftriaxone.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rabbit meningitis model.

The meningitis model, originally described by Dacey and Sande (6), was slightly modified. The experimental protocol was accepted by the local ethical committee (Veterinäramt des Kantons Bern). Briefly, young New Zealand White rabbits weighing 2 to 2.5 kg were anesthetized by intramuscular injections of ketamine (30 mg/kg of body weight) and xylazine (15 mg/kg), and were immobilized in stereotactic frames for induction of meningitis and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samplings. An inoculum containing approximately 106 CFU of penicillin-resistant pneumococci serotype 6 was directly injected into the cisterna magna. The pneumococcal strain had originally been isolated from a patient with pneumonia at the University Hospital of Bern, Bern, Switzerland. The MICs were as follows (in milligrams per liter): penicillin, 4; ceftriaxone, 0.5; vancomycin, 0.12 to 0.25; and gentamicin, 4.

A long-acting anesthetic (ethyl carbamate [urethane] 3.5 g/rabbit) was injected subcutaneously, and animals were returned to their cages. Fourteen hours later, a catheter was introduced into the femoral artery for serum sampling, and the cisterna magna was punctured again for periodic CSF sampling before and 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after initiation of therapy. Anesthesia was performed by repetitive intravenous (i.v.) injections of nembutal. Antibiotics were administered through a peripheral ear vein as bolus injections at the following concentrations: gentamicin, 10 mg/kg; vancomycin, 20 mg/kg; and ceftriaxone, 125 mg/kg. Gentamicin and ceftriaxone were injected once at h 0, and vancomycin was injected at h 0 and 4 according to the literature (1, 11). Untreated controls received saline. Bacterial titers were measured by 10-fold serial dilutions of CSF samples, plated on blood agar plates containing 5% sheep blood, and incubated overnight at 37°C. In parallel, 20 μl of undiluted CSF samples was plated (limit of detectability, 50 CFU/ml). Comparison between different dilutions of CSF was used to exclude significant carryover effects during therapy. At the end of the experiment, euthanasia was induced by a lethal i.v. dose of nembutal. The antimicrobial activity of the regimens during the 8-h treatment was calculated by linear regression analysis and expressed as a decrease of log10 CFU per milliliter per hour and as the killing rate after 8 h. A value of 1.7 (log10 of the limit of detectability) was assigned to the first sterile CSF sample, and a value of 0 was assigned to any subsequent sterile sample. The results were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was determined by the Tukey multiple comparisons test. All antibiotics and anesthetic drugs were commercially purchased.

Measurement of antibiotic levels in the CSF.

Antibiotic concentrations in the CSF were determined by agar diffusion method. Standard curves were performed in saline with 5% rabbit serum in order to mimic the protein concentration in CSF during meningitis (5). Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633 was used as a test strain for vancomycin and gentamicin (7). The intra- and interday variability of this method was less than 10%. The limits of detection were 0.5 mg/liter for vancomycin, and 0.10 mg/liter for gentamicin.

In vitro assays.

The pneumococcal strain was grown in C + Y medium (8) to an optical density at 590 nm of 0.3 and then diluted 40-fold to 106 CFU/ml, corresponding to the CSF bacterial titer in rabbits before initiation of therapy. Gentamicin was added in concentrations corresponding to one time the MIC (4 mg/liter), corresponding to levels achieved in the CSF; vancomycin was added in concentrations ranging from one to two times the MIC. Combination therapy with vancomycin and gentamicin was also tested. Bacterial titers were determined at h 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 by serial dilution of samples; plated on agar plates containing 5% sheep blood; and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and results are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Synergy was defined as bactericidal effect of a drug combination greater than 2-log killing over the most active drug alone.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

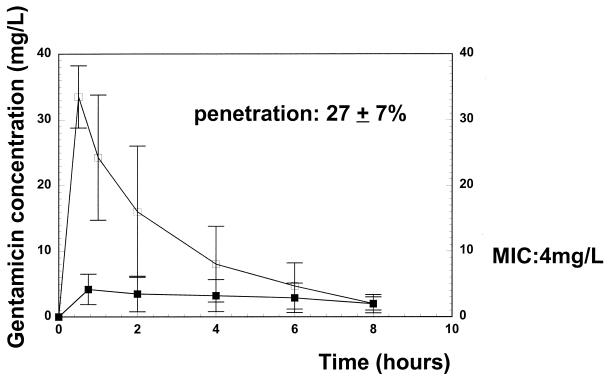

We decided to administer gentamicin in a single dose in order to produce higher levels in CSF than were achievable by conventional multiple daily dosing during the major part of the treatment period (1). A single injection of gentamicin led to peak levels in serum of around 33 mg/liter, declining to 2 mg/liter 8 h later. The peak levels in CSF ranged around 4.3 mg/liter, and the trough levels were around 2.2 mg/liter at the end of the treatment period. The CSF penetration by gentamicin was calculated for each animal by comparison of serum and CSF areas under the curve (AUC) (Systat software; SSPP Inc., Evanston, Ill.). In our model, the penetration of gentamicin into the CSF was 27% ± 7%, confirming previous studies (1). The CSF gentamicin levels remained around the MIC (4 mg/liter) for approximately 4 h (Fig. 1). The peak concentrations of gentamicin in serum were similar to those observed in humans after one single-dose regimen (10). The CSF vancomycin levels ranged between 3.5 and 1.5 mg/liter, remaining above the MIC during the entire treatment period (data not shown), and corresponded to levels achieved in humans (2, 11).

FIG. 1.

Gentamicin concentrations during 8 h in serum and CSF after a single dose of gentamicin (10 mg/kg). Open squares represent serum drug levels, and solid squares represent CSF drug levels. The concentration of gentamicin remained around the MIC (4 mg/liter) for approximately 4 h. Vertical bars represent ± standard deviation.

The killing rates of the different regimens are summarized in Table 1. Gentamicin monotherapy produced a negligible antibacterial activity due to the pharmacokinetic profile of a single dose of gentamicin leading to CSF gentamicin levels around the MIC only during half of the treatment period (Fig. 1). In our experimental model, vancomycin as either monotherapy or combined with ceftriaxone showed antibacterial activities comparable to those described previously (8, 5, 13). It is interesting to note that the addition of vancomycin to gentamicin led to a synergy and significantly increased the killing rate of gentamicin, producing an antimicrobial activity comparable to that of the standard regimen (vancomycin plus ceftriaxone). The synergistic activity between vancomycin and gentamicin was also found in vitro in time-kill assays over 8 h. In this experimental setting, a gentamicin concentration of one time the MIC (4 mg/liter) was selected, corresponding to levels achieved in the CSF of rabbits.

TABLE 1.

Gentamicin, vancomycin, and combination therapy against penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae in experimental meningitisa

| Antibiotic | (n) | Initial titer (log10 CFU/ml) | Killing rate (Δlog10 CFU/ml · h)b | Killing rate over 8 h (log10 CFU/ml)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | (5) | 6.30 ± 0.64 | +0.05 ± 0.10* | +0.25 ± 0.12* |

| Gentamicin | (7) | 6.02 ± 1.38 | −0.18 ± 0.32 | −1.24 ± 0.54†,‡ |

| Vancomycin | (7) | 6.53 ± 1.25 | −0.35 ± 0.20 | −2.54 ± 0.80†,‡ |

| Vancomycin + ceftriaxone | (7) | 6.05 ± 0.15 | −0.52 ± 0.27 | −4.10 ± 0.90§ |

| Vancomycin + gentamicin | (7) | 6.28 ± 0.87 | −0.57 ± 0.18 | −4.48 ± 1.00‡,§ |

Values are means ± standard deviation.

*, P < 0.05 versus all groups; †, P < 0.05 for vancomycin versus gentamicin (Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test); ‡, P < 0.001 for vancomycin plus gentamicin versus all monotherapies (Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test); §, P not significant for vancomycin plus ceftriaxone versus vancomycin plus gentamicin.

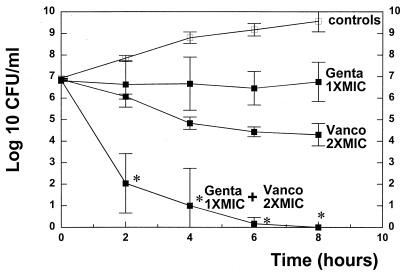

Addition of vancomycin in higher concentrations (two times the MIC) clearly resulted in synergy and sterilized the cultures after 6 h (Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained with another penicillin-resistant pneumococcal strain (KR4) in vitro (MIC of penicillin, 4 mg/liter; MIC of gentamicin, 4 mg/liter) (data not shown). Improved activity of gentamicin in vitro by addition of vancomycin has already been described, without reaching an extent qualifying as synergy (9). The reasons for the synergy observed in vitro by increasing the vancomycin dose is not clear, but is reminiscent of the synergy between β-lactam antibiotics as cell wall-active antibiotics and aminoglycosides observed in enterococci. A synergy between amoxicillin and gentamicin against resistant pneumococci has already been observed in a mouse pneumonia model (77).

FIG. 2.

Solid squares represent killing rates of vancomycin (Vanco2XMIC [0.25 mg/liter]), gentamicin (Genta1XMIC: [4 mg/liter]), and the combination of the two antibiotics (Genta1X MIC + Vanco 2XMIC) in vitro. Open squares represent untreated controls. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. *, P < 0.05 versus either single drug therapy.

Based on our data, it is obvious that gentamicin cannot be recommended as monotherapy for pneumococcal meningitis due to resistant strains because of its insufficient penetration into the CSF and its narrow safety profile. However, gentamicin combined with vancomycin could be a conceivable alternative regimen, especially in case of β-lactam allergy. These data deserve further evaluation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed, A., M. M. Paris, M. Trujillo, S. M. Hickey, L. Wubbel, S. L. Shelton, and G. H. McCracken, Jr. 1997. Once-daily gentamicin therapy for experimental Escherichia coli meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, A. 1997. A critical evaluation of vancomycin for treatment of bacterial meningitis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 16:895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley, J., and W. M. Scheld. 1997. The challenge of penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis: current antibiotic therapy in the 1990s. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24(Suppl. 2):213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley, J. S., and J. D. Connor. 1991. Ceftriaxone failure in meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to β-lactam antibiotics. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:871–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cottagnoud, P., F. Acosta, M. Cottagnoud, K. Neftel, and M. G. Täuber. 2000. Synergy between trovafloxacin and ceftriaxone against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2179–2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dacey, R. G., and M. A. Sande. 1974. Effect of probenecid on cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of penicillin and cephalosporin derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6:437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Darras-Joly, C., J. P. Bédos, C. Sauve, P. Moine, E. Vallée, C. Carbon, and E. Azoulay-Dupuis. 1996. Synergy between amoxicillin and gentamicin in combination against a highly penicillin-resistant and -tolerant strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a mouse pneumonia model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2147–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedland, I. R., M. Paris, S. Ehrett, S. Hickey, K. Olsen, and G. H. McCracken, Jr. 1993. Evaluation of antimicrobial regimens for treatment of experimental penicillin- and cephalosporin-resistant pneumococcal meningitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1630–1636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedland, I. R., M. Paris, S. Shelton, and G. H. McCracken. 1993. Time-kill studies of antibiotic combinations against penicillin-resistant and -susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 34:231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilbert, D. N. 1991. Once-daily aminoglycoside therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawley, H. B., and D. W. Gump. 1973. Vancomycin therapy in bacterial meningitis. Am. J. Dis. Child. 126:261–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quagliarello, V. J., and M. W. Scheld. 1997. Treatment of bacterial meningitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 336:708–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodoni, D., F. Hänni, C. M. Gerber, M. Cottagnoud, K. Neftel, M. G. Täuber, and P. Cottagnoud. 1999. Trovafloxacin in combination with vancomycin against penicillin-resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:963–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sloas, M. M., F. F. Barrett, P. J. Chesney, B. K. English, B. C. Hill, F. C. Tenover, and R. J. Leggiardo. 1991. Cephalosporin treatment failure in penicillin- and cephalosporin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Ped. Infect. Dis. J. 11:662–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]