Abstract

We report on the antiproliferative effects and the ultrastructural and biochemical alterations induced in vitro by 22,26-azasterol, a sterol Δ24(25)-methyltransferase (24-SMT) inhibitor, on Leishmania amazonensis. When promastigotes and amastigotes were exposed to 100 nM 22,26-azasterol, complete growth arrest and cell lysis ensued after 72 (promastigotes) or 120 (amastigotes) h. Exposure of parasites to this azasterol led to the complete depletion of parasite endogenous sterols (episterol and 5-dehydroepisterol) and their replacement by 24-desalkyl sterols (zymosterol, cholesta-5,7,24-trien-3β-ol, and cholesta-7,24-dien-3β-ol), while 14-methyl-zymosterol and 4,14-dimethyl-zymosterol accumulated as a result of simultaneous incubation of the parasites with 22,26-azasterol and ketoconazole, a known inhibitor of the parasite’s sterol C14-demethylase. These results confirmed that 24-SMT is the primary site of action of the azasterol. Profound changes were also observed in the phospholipid compositions of treated cells, in which a twofold reduction in the content of phosphatidylserine was observed; this was accompanied by a concomitant increase in the content of phosphatidylinositol. Transmission electron microscopy showed that 22,26-azasterol induced marked morphological changes, including mitochondrial swelling, invaginations of the inner mitochondrial membrane, and the appearance of large bodies containing concentric membranes. Other modifications included increases in the numbers of acidocalcisomes, megasomes, and lipid inclusions and the appearance of typical autophagic structures and cell body protrusions toward the flagellar pocket. We conclude that the dramatic alteration of the lipid composition of the parasite’s membranes induced by the drug underlies the ultrastructural alterations that lead to the loss of cell viability and that 24-SMT inhibitors could be useful as selective antileishmanial agents.

Leishmaniasis, a parasitosis caused by organisms of the Leishmania genus, comprises three clinical forms: visceral, cutaneous, and mucocutaneous. These infections are associated with significant rates of morbidity and mortality throughout the world. The lesions may be confined to skin, in the case of cutaneous leishmaniasis, or may invade subcutaneous tissue, as in the potentially fatal visceral form, depending on the infecting organism and the immunological status of the host (26).

Chemotherapeutic treatment of leishmaniasis usually relies on the use of pentavalent antimonials such as sodium stibogluconate (Pentostam) and meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime), but toxic side effects and drug resistance are frequently encountered (10, 25, 26, 30). The second-line compounds used during the treatment of unresponsive cases generally include pentamidine and amphotericin B (10, 15, 26, 32, 65. Antifungal imidazole and triazole derivatives such as ketoconazole and itraconazole, which block ergosterol biosynthesis at the level of cytochrome P-450-dependent C14-demethylase (10, 19, 47, 48, 49, 56, 57, 58, 59), are also effective against different Leishmania species both in vitro and in vivo (6–10, 30, 34, 61). Ketoconazole seems to be more effective against infections caused by Leishmania mexicana than L. braziliensis (30, 37). A second group of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors (EBIs) includes the allylamines, which act on earlier steps of the ergosterol biosynthetic pathway by inhibiting squalene synthetase (50) or squalene epoxidase (34, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44). L. braziliensis promastigotes are naturally resistant to ketoconazole but become highly susceptible in the presence of the allylamine terbinafine (37). The growth of L. amazonensis is very susceptible to inhibition by ketoconazole and terbinafine in vitro (61).

Recent studies have described the antiproliferative effects of the inhibitors of the Δ24(25)- and Δ24(24′)-sterol methyltransferases. These enzymes, which catalyze the S-adenosylmethionine-mediated incorporation of methenyl groups at position 24 in sterols, are essential for the biosynthesis of fungal and protozoal sterol molecules. Indeed, inhibitors of these enzymes have been shown to be antiproliferative agents against yeasts, fungi, and plants in vitro (2, 11, 28, 31, 36). One important feature is the absence of this enzyme in the sterol of the parasite’s vertebrate host, which exclusively produces the 24-desalkyl sterol cholesterol (54). 20-Piperidin-2-yl-5α-pregnan-3β-20(R)-diol (22,26-azasterol; Fig. 1) is an inhibitor of Δ24(25)-sterol methyltransferase (24-SMT) in fungal cells (2) and in both epimastigotes and amastigotes of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (23, 52, 53); it has also been shown that this compound is a potent antiproliferative agent against this parasite both in vitro and in vivo (52, 53). Pneumocystis carinii, an opportunistic fungal pathogen which, in contrast to other fungi, is completely resistant to azoles and ampthotericin B (3, 4, 13, 27, 45), is also susceptible to 22,26-azasterol in vitro (55).

FIG. 1.

Molecular structure of 22,26-azasterol. Me, methyl.

In this report, we describe the antiproliferative effects and the associated ultrastructural and biochemical alterations produced by 22,26-azasterol on promastigote and amastigote forms of L. amazonensis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites.

The MHOM/BR/75/Josefa strain of L. amazonensis isolated from a patient with diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis by C. A. Cuba-Cuba (Universidade de Brasilia, Brazil) was used in the present study. It has been maintained by hamster footpad inoculation and, in the case of promastigotes, axenically cultured in Warren’s medium (brain heart infusion plus hemin and folic acid) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 25°C. Axenic amastigote cultures were maintained in Schneider’s insect medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) with 20% fetal bovine serum at 32°C (33). Cell densities were determined daily in a hemocytometer with a light microscope.

Electron microscopy.

Control and treated parasite cells were fixed for 3 h at 4°C in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma Chemical Co.) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2). After fixation, the cells were postfixed for 30 min in a solution containing 1% OsO4 and 0.8% potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, washed in the same buffer, dehydrated in acetone, and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and were observed in a Zeiss 900 electron microscope.

Three-dimensional reconstructions.

Promastigotes axenically grown in the presence or absence of 100 nM 22,26-azasterol for 24 h were processed for electron microscopy as described above. For serial sectioning, the blocks were trimmed with a very narrow face and sharp edges. The leading edge of the block was coated with a diluted solution of arabic gum in chloroform to make sure that the sections would form a ribbon. Ultrathin sections 60 to 100 nm thick were cut in a Reichert Ultracut E ultramicrotome a with a diamond knife, and ribbons were collected on uncoated single-slot copper grids (1.2 by 2.0 mm). Surface tension kept the ribbons correctly oriented in the slot, and the ribbon-containing grids were immediately placed over Formvar films stretched over a plastic ring. This procedure avoided Formvar film shrinkage and ribbon folding, which is common when ribbons are collected on precoated grids. After the grids dried they were stained with uranyl acetate for 40 min and lead citrate for 5 min and allowed to dry. Series of longitudinally oriented cells were followed and photographed at a magnification of ×20,000 on a Zeiss 900 transmission electron microscope. Serial micrographs were printed at a final magnification of ×50,000. The cell membrane, mitochondria, concentric membranes in mitochondrial matrix, flagellar pocket, nucleus, and Golgi complex were outlined on each micrograph with distinct colors, and each plane was separately traced in a digitizing table (Numonics 2205) into a three-dimensional reconstruction program for serial sections (66). The resulting data files consisted of contour outlines representing cross sections of the objects of interest within the volume. The files were then transferred to a Silicon Graphics workstation, and surfaces between planes were generated with the software package SYNU (synthetic universe) (20). Selected images were photographed in a Polaroid digital palette film recorder system.

Studies of lipid composition.

For the analysis of the effects of drugs on the lipid compositions of the promastigotes, total lipids from control and drug-treated cells were extracted and fractionated into neutral and polar lipid fractions by silicic acid column chromatography and gas-liquid chromatography (23, 52, 53). The neutral lipid fractions were first analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (on Merck 5721 silica gel plates with heptane-isopropyl ether-glacial acetic acid [60:40:4] as the developing solvent) and conventional gas-liquid chromatography (isothermic separation in a 4-m glass column packed with 3% OV-1 on Chromosorb 100/200 mesh, with nitrogen as the carrier gas at 24 ml/min and flame ionization detection in a Varian 3700 gas chromatograph). For quantitative analysis and structural assignments, the neutral lipids were separated in a capillary high-resolution Ultra-2 column (25 m by 0.20 mm [inner diameter]; 5% phenylmethyl-siloxane; (film thickness, 0.33 μm) in a Hewlett-Packard 6890 series II gas chromatograph equipped with an HP5973A mass-sensitive detector. The lipids were injected in ethyl acetate, and the column was kept at 50°C for 1 min. The temperature was then increased to 270°C at a rate of 25°C · min−1 and finally to 300°C at a rate of 1°C · min−1. The carrier gas (He) flow was kept constant at 1.0 ml · min−1. The injector temperature was 250°C, and the detector was kept at 280°C. The polar lipid fraction (containing mostly phospholipids) was analyzed as described before (12); briefly, the lipid fractions that eluted from the silicic acid column with chloroform-methanol (1:1 [vol/vol]) were pooled and further fractionated by thin-layer chromatography on Merck 5721 silica gel plates with chloroform-methanol-32.5% (vol/vol) ammonia (17:7:1, by vol) as the developing solvent (14). The phospholipid spots were visualized with iodine and scraped off the silica gel plates, and the total organic phosphorus was measured by the method of Ames and Dubin (1).

Drugs.

22,26-Azasterol was synthesized and purified as described before (52), while ketoconazole was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, Mo.). They were added to parasite cultures as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solutions, the final DMSO concentration never exceeded 1% (vol/vol), and it had no effect on the proliferation of parasites. Stock solutions were stored at 0 to 4°C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Antiproliferative effects.

The addition of 100 nM 22,26-azasterol to the culture medium of L. amazonensis induced a delayed lytic effect; i.e., growth arrest and cell lysis were observed 72 h after the addition of the drug. The 1 μM concentration of this azasterol induced 50% growth inhibition after 24 h (Fig. 2A). The viabilities of treated and nontreated parasite cells were assessed by the dye exclusion test, cell morphology, motility, and ultrastructural appearance. In the case of axenic amastigote forms, total growth arrest was observed in cultures incubated in the presence of 100 nM 22,26-azasterol after 120 h (Fig. 2B). The delayed onset of growth inhibition and cell lysis coincide with the depletion of the parasite’s endogenous sterols (see next section) and are not consistent with a direct effect of the azasterol on the parasite membranes; if the azasterol had a direct effect, it should have induced immediate effects on cell morphology and division. In P. carinii 22,26-azasterol induced the reduction of growth, with a 50% inhibitory concentration of 300 nM and an 80% reduction of growth after 96 h at 10 μM (54, 55). The minimum growth-inhibitory concentrations of 22,26-azasterol for T. cruzi epimastigotes and intracellular amastigotes are 10 μM and 100 nM, respectively, after 96 h of incubation (52, 53). Therefore, both L. amazonensis proliferative stages are more susceptible to 22,26-azasterol than extracellular P. carinii and T. cruzi forms but are as susceptible as intracellular stages of T. cruzi.

FIG. 2.

Effect of azasterol on the growth of L. amazonensis promastigotes (A) and amastigotes (B). Parasites of both forms were incubated as described in Materials and Methods, and the drug was added to the cultures at 0 h. The cells were counted daily. ⧫, control; ▪, DMSO-treated control; ▴, treatment with 0.1 μM azasterol; * (top), treatment with 1.0 μM azasterol; * (bottom), treatment with 10 μM azasterol. The bars indicate standard deviations.

Over the concentration range studied, axenic amastigotes were about 100-fold more suceptible to 22,26-azasterol than promastigotes (Fig. 2). Similar results were observed when the susceptibilities of epimastigotes and amastigotes of T. cruzi were compared (23, 53). It has been proposed, on the basis of detailed biochemical studies, that the greater susceptibility of the intracellular T. cruzi amastigote to EBIs is due to their smaller pools of preformed sterols (23).

Effects of 22,26-azasterol and ketoconazole on promastigote’s lipid composition.

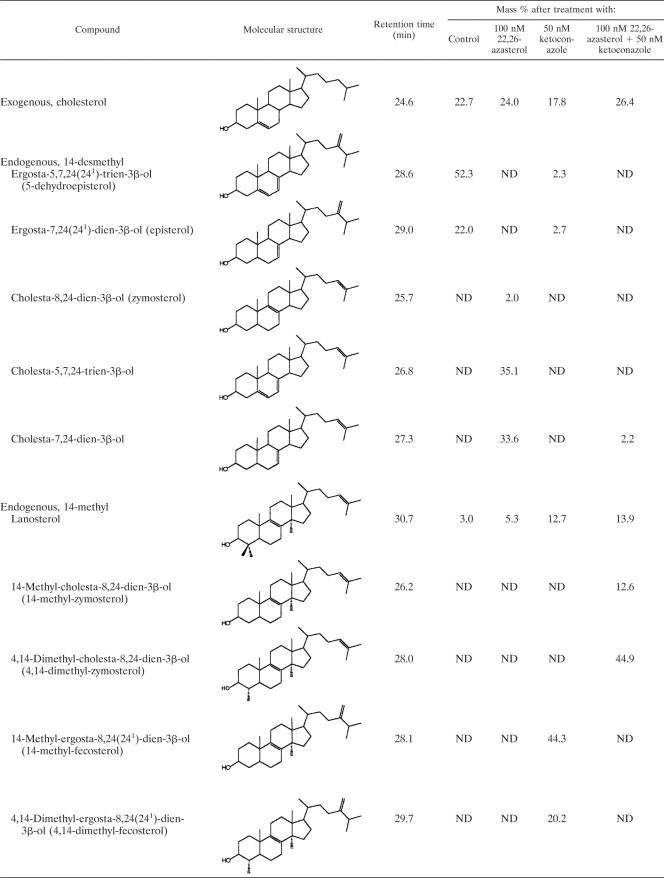

Neutral and polar lipids were extracted from both control (untreated) and drug-treated promastigotes and analyzed, as described in Materials and Methods. Two independent experiments were carried out, with essentially identical results. Table 1 shows that in cells exposed to 22,26-azasterol at the MIC (100 nM) for 72 h, at which time complete growth arrest and cell lysis ensued, essentially all the parasite’s endogenous free sterols, episterol [ergosta-7,24(241)-dien-3β-ol)] and 5-dehydroepisterol (17, 37), were replaced by 24-desalkyl sterols such as cholesta-5,7,24-trien-3β-ol and cholesta-7,24-dien-3β-ol, with lower levels of cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol (zymosterol). These results coincide with those obtained by Haughan et al. (18) with L. donavani promastigotes and also with those obtained by Urbina and colleagues (23, 52, 53) with both epimastigotes and amastigotes of T. cruzi. When these cells were incubated in the presence of 50 nM ketoconazole, a known inhibitor of the sterol C14-demethylase of fungi and trypanosomatid parasites (37, 54), the normal parasite sterols were replaced by lanosterol, 4,14-dimethyl-fecosterol, and 14-methyl-fecosterol (Table 1); a simultaneous incubation of the cells with 100 nM 22,26-azasterol and 50 nM ketoconazole led instead to the accumulation of lanosterol, 4,14-dimethyl-zymosterol, and 14-methyl-zymosterol (Table 1). Taken together, these results support the notion that the primary mechanism of action of 22,26-azasterol against trypanosomatids is inhibition of 24-SMT, as is found in fungi, yeasts, and plants (2, 11, 28, 31, 36). They also indicate that 24-SMT in L. amazonensis can use zymosterol or its 14-methyl or 4,14-dimethyl derivatives as substrates, as reported before for L. braziliensis and L. mexicana (40); similar results were obtained with T. cruzi (23, 52, 53). In contrast, Beach et al. (6) report for other strains of L. mexicana, L. tropica, and L. donovani that the main sterols which accumulated in cells incubated with ketoconazole were lanosterol, 4,14-dimethyl-zymosterol, and 14-methyl-zymosterol, which indicated that for these organisms the substrate specificity of 24-SMT is restricted to zymosterol. In Fig 3 we present a minimum metabolic model for the de novo synthesis of sterols in L. amazonensis promastigotes, consistent with the results of the present and previous studies (6, 40).

TABLE 1.

Effects of 22,26-azasterol and ketoconazole on free sterol composition of L. amazonensis promastigotesa

Sterols were extracted from cells exposed to drug at the indicated concentration for 72 h; they were separated from polar lipidis by silic acid column chromatography and analyzed by quantitative capillary gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. ND, not detected.

FIG. 3.

Minimum model for the sterol biosynthesis pathway in L. amazonensis promastigotes. I, squalene; II, lanosterol; III, 4,14-dimethyl-zymosterol; IV, 14-methyl-zymosterol; V, 4,14-dimethyl-fecosterol; VI, 14-methyl-fecosterol; VII, cholesta-8,24-dien-3β-ol (zymosterol); VIII, cholesta-5,8,24-trien-3β-ol; IX, cholesta-7,24-dien-3β-ol; X, cholesta-5,7,24-trien-3β-ol; XI, ergosta-7,24(241)-dien-3β-ol (episterol); XII, ergosta-5,7,24(241)-trien-3β-ol (5-dehydroepisterol); XIII, ergosterol. SQSI, squalene synthase inhibitors; SEI, squalene epoxidase inhibitors; SMTI, sterol methyltransferase inhibitors; SMRI, sterol methylreductase inhibitors; SDMI, sterol 14-demethylase inhibitors. See text for details.

When the polar lipid (mainly phospholipid) fraction was analyzed, it was found (Table 2) that in control promastigotes the main phospholipid components were phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylserine (PS), and phosphatidylcholine (PC), with smaller amounts of sphingomyelin (SPM) and phosphatidylinositol (PI). The results differ quantitatively from those reported by Beach et al. (5) for L. tarentaolae, where PC and PE were found to be the main phospholipid species and no significant levels of PS were detected. In L. amazonensis promastigotes treated with 100 nM 22,26-azasterol for 72 h, marked differences in their phospholipid contents compared with those of control cells were found (Table 2): a twofold reduction in the relative content of PS with a concomitant twofold increase in PI levels, accompanied by smaller increases in the levels of choline-containing phospholipids (PC and SPM). These changes indicate a marked increase in the relative activity of PI synthase over that of PS synthase, two membrane-bound enzymes that compete for their common substrate, CDP-diacylglycerol (38); the results also suggest an increase in the activity of PC (SPM)-PE-N-methyltransferases. Contreras et al. (12) have also found previously that treatment of T. cruzi epimastigotes with 22,26-azasterol or other EBIs leads, together with the expected changes in sterol composition, to profound changes in their phospholipid compositions. We interpreted these changes as resulting from alterations of the activities of phospholipid biosynthetic enzymes due to the altered sterol composition.

TABLE 2.

Effects of 22,26-azasterol on phospholipid composition of L. amazonensis promastigotesa

| Phospholipid species | Mol % after treatment with:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control (no drug) | 100 nM 22,26-azasterol | |

| PC | 13.9 | 17.5 |

| PE | 34.5 | 31.5 |

| PI | 10.4 | 19.0 |

| PS | 31.8 | 15.7 |

| SPM | 9.4 | 15.4 |

Promastigotes were grown in Warren’s medium with and without the indicated drug concentration for 72 h, and polar lipids were separated from the total lipid extract by silic acid column chromatography and thin-layer chromatography, as described in Materials and Methods. The different phospholipid species present were quantified by measuring organic phosphorus levels. The results are the means of two independent experiments.

Effect of 22,26-azasterol on fine structure of L. amazonensis.

The general structures of promastigote and amastigote forms of L. amazonensis seen by transmission electron microscopy of thin sections have been described previously (35). During the present study, controls were carried out in which the parasites were incubated in the presence of 0.1% DMSO, the same concentration found in the final solutions of 22,26-azasterol used to incubate the parasites. As shown in Fig. 4 and 5, with this concentration of the solvent the promastigote and amastigote forms showed normal morphologies.

Figure 4-6.

FIG. 4–5: Electron micrographs of promastigote and amastigote forms of L. amazonensis showing a normal morphology in the presence of 0.1% DMSO, the same concentration of DMSO as in the final solutions of azasterol used. N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast; FP, flagellar pocket; M, mitochondrion; GC, Golgi complex. Bars, 1 μm.

FIG. 6: Promastigote treated with 1.0 μM azasterol for 24 h. This parasite presented a protrusion of the cell body toward the flagellar pocket (arrow). Bar, 0.5 μm.

Parasites incubated in the presence of 22,26-azasterol showed significant morphological changes, which varied from discrete alterations to total destruction of the parasite, depending on the drug concentration and the time of incubation. One of the first indications of morphological changes in drug-treated parasites took place in the region of the flagellar pocket; these changes appeared as protrusions of the cell body toward the pocket (Fig. 6) and as concentric membranes within the pocket (see Fig. 10 and 11). In Fig. 7 to 9 we show a sequence of protrusions on the flagellar pocket; these images suggest that protrusions are formed by the plasma membrane and are then released from the cell body with a portion of the cytoplasm. At present we do not have a clear explanation for the mechanisms involved in these changes. The presence of protrusions indicates a change in the plasticity of the membrane lining the flagellar pocket from its normal disposition, allowing the formation of exocytic projections. Protrusions were not seen in other portions of the plasma membrane. However, it is important to point out that in all regions except the flagellar pocket, a layer of subpellicular microtubules underlies the plasma membrane, making the formation of such structures difficult (35). Concerning the concentric membranes seen in the flagellar pocket, we cannot exclude the possibility that they result from the secretion into this region of abnormal lipids, which accumulate as a consequence of the drug action (see the previous section) and then assemble in these concentric, myelin-like figures, probably due to their different physical properties (51). Indeed, some images obtained, as shown in Fig. 10 to 12, strongly suggest an intense secretory process with the appearance of various membranous structures within the pocket. It is well established that the flagellar pocket is the main site of endocytic (46) and exocytic (60, 64) activity in trypanosomatids. Previous studies have shown that when L. amazonensis cells are incubated in the presence of 12-O tetradecanoyl phorbol-13-acetate, an activator of proteinase kinase C, a marked increase in the exocytic activity occurs, with the appearance of membranous structures within the pocket similar to those observed in parasites treated with 22,26-azasterol (60).

FIG. 10–13.

Amastigote forms treated with 0.1 μM azasterol for 72 h (Fig. 10) and 1.0 μM azasterol for 48 h (Fig. 11) presented myelin-like figures within flagellar pocket (arrows). In Fig. 11 we observed a megasome (asterisk). N, nucleus; K, kinetoplast; FP, flagellar pocket. Bars, 0.5 μm.

FIG. 7–9.

Protrusions of the flagellar pocket in sequence. The promastigote form was treated with 1.0 μM azasterol for 24 h. The arrows show the protrusions formed by the membrane, and the stars show the vesicles released from the cell body into the flagellar pocket. FP, flagellar pocket. Bars, 1.0 μm.

Another early change observed in 22,26-azasterol-treated parasites takes place in the mitochondrion. This modification started at the inner mitochondrial membrane, which folded toward the mitochondrial matrix, forming complex and elaborate structures which could be seen in conventional sections (Fig. 13) and which were better visualized in three-dimensional reconstructions of treated cells (Fig. 20); control (untreated) parasites analyzed in the same manner had normal mitochondrial ultrastructures (Fig. 18 and 19). Subsequently, the mitochondrial matrix in cells incubated with the azasterol became less electron dense, and later, a typical swelling of the mitochondrion was observed (Fig. 14 and 15). In some cells the intense swelling facilitated the visualization of all regions of this highly ramified organelle (Fig. 14). In a previous study we observed the same type of mitochondrial alterations in T. cruzi epimastigotes and amastigotes treated with 22,26-azasterol (63), as well as in T. cruzi and L. amazonensis incubated in the presence of other EBIs such as ICI 195,739 (22), ketoconazole, and terbinafine (21, 61). Taken together, these observations suggest that the presence of ergosterol and analogs is essential for the maintenance of a normal structural organization of the mitochondrial membrane in trypanosomatids, especially the inner one. Recent biochemical studies have shown that, contrary to what is known for mammalian cells, there are large amounts of endogenous and exogenous sterols in the mitochondrial membranes of trypanosomatids (39). Our present observations, in association with other observations published previously, also indicate that the special mitochondrion present in trypanosomatids is one important target in chemotherapy.

FIG. 18–20.

Three-dimensional reconstruction images showing the control promastigote form presenting a normal morphology in the mitochondria. Gray, plasma membrane; blue, nucleus; green, mitochondria; pink, kinetoplast; brown, Golgi complex. We did not observe concentric membranes in the mitochondrial matrix in control cells.

Figure 14-17.

FIG. 14–15: Promastigotes treated with 10 μM azasterol for 48 h (Fig. 14; stars) and 1.0 μM azasterol for 48 h (Fig. 15; asterisks) presented intense mitochondrial swelling. N, nucleus. Bars, 1 μm (Fig. 14) and 0.5 μm (Fig. 15).

FIG. 16: Electron micrograph showing increases in the numbers of acidocalcisomes (arrowheads) in association with the endoplasmic reticulum. Bar, 0.5 μm.

FIG. 17: Ultrathin section of promastigote form treated with azasterol showing the mitochondrion enveloping by endoplasmic reticulum (arrows). N, nucleus. Bar, 0.5 μm.

A third important morphological change observed in treated cells was a significant increase in the number of some organelles in drug-treated cells, such as (i) acidocalcisomes, which are organelles that appear as vacuoles containing an electron-dense content (Fig. 16) and that are involved in polyphosphate storage and control of the intracellular calcium concentrations in trypanosomatid and apicomplexan parasites (16, 29) (previous studies [62] have shown that other drugs such as ketoconazole and terbinafine produce the same effect), and (ii) megasomes, which are lysosome-like structures typically found in the amastigote form of the complex Leishmania mexicana (Fig. 11). We also observed a dramatic increase in the number of autophagosomal structures, characterized by the presence of profiles of the endoplasmic reticulum surrounding various organelles such as the acidocalcisomes and mitochondrion (Fig. 15 to 17). Other studies have shown that various drugs, such as suramin (24), induce the appearance of autophagic bodies in drug-treated parasites. The appearance of an increased number of autophagosomal structures (Fig. 21 and 22) probably involved in the breakdown and recycling of abnormal membrane structures strongly suggests the existence of an intense process of remodeling of intracellular organelles irreversibly damaged by the drug used. Other related morphological changes observed include increases in the numbers of lipidic inclusions and the presence of concentric membranes in the cytoplasm (Fig. 21). These features are characteristic of autophagic processes and could again be associated with the accumulation of aberrant lipids (see above), which are probably not wholly incorporated into the plasma membrane or the membranes lining the various cellular organelles.

Figure 21-22.

FIG. 21-22.

Promastigote treated with 10 μM azasterol for 24 h presented a myelin-like figure in the cytoplasm (arrows). Bar, 0.5 μm.

Ultrathin section of promastigote treated with 0.1 μM azasterol for 48 h showing proliferation in the number of autophagosomal structures (asterisks). Bar, 0.5 μm.

In conclusion, 22,26-azasterol is a very potent in vitro inhibitor of growth of both proliferative stages of L. amazonensis, probably acting via alteration of the sterol and indirectly via alteration of the phospholipid compositions of these cells, which in turn leads to irreversible alterations to subcellular structures and cell lysis. Similar results at the biochemical level have been obtained previously with L. donovani (18) and more recently with L. mexicana (J. A. Urbina et al., unpublished data). In vivo studies have shown that this compound has selective antiparasitic activity in a murine model of acute Chagas’ disease (53), and studies with murine models of leishmaniasis are also being performed.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Commission (contract ERB IC18-CT98-0371 to W.D. and J.A.U.), the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (grant 75301-554202 to J.A.U.), Programa de Núcleos de Excelência (PRONEX), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ). We are grateful to the National Center for Microscopy and Image Research, San Diego, Calif., supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant NIHRR0450 to Mark H. Ellisman, for the use of its facilities.

J.A.U. is grateful to Dhuwya Otero and Luis Alvarez for help with the preparation of Fig. 3. J.C.F.R. thanks Rossiane Cláudia Vommaro for critical reading of the manuscript.

J.A.U. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Research Scholar.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames, B., and D. Dubin. 1960. The role of polyamines in the neutralization of deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 235:769–775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barret-Bee, K., and N. S. Ryder. 1992. Biochemical aspects of ergosterol biosynthesis inhibition, p.410–436. In J. Sutcliffe and N. H. Georgopapadakou (ed.), Emerging targets in antibacterial and antifungal chemotherapy. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Bartlett, M. S., and J. W. Smith. 1991. Pneumocystis carinii, an opportunist in immunocompromised patients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 4:137–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartlett, M. S., S. F. Queener, M. M. Shaw, J. D. Richardson, and J. W. Smith. 1994. Pneumocystis carinii is resistant to imidazole antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1859–1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beach, D. H., G. G. Holz, Jr., and G. E. Anekwe. 1979. Lipids of Leishmania promastigotes. J. Parasitol. 65:203–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beach, D. H., L. J. Goad, and G. G. Holz, Jr. 1988. Effects of antimycotic azoles on growth and sterol biosynthesis of Leishmania promastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 31:149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berman, J. D. 1981. Activity of imidazoles against Leishmania tropica in human macrophage cultures. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 30:566–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman, J. D., G. G. Holz, Jr., and D. H. Beach. 1984. Effects of ketoconazole on growth and sterol biosynthesis of Leishmania mexicana promastigotes in culture. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 12:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berman, J. D., L. J. Goad, D. H. Beach, and G. G. Holz, Jr. 1986. Effects of ketoconazole on sterol biosynthesis by Leishmania mexicana mexicana amastigotes in murine macrophage tumor cells. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 20:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berman, J. D. 1988. Chemotherapy of leishmaniasis: biochemical mechanisms, clinical efficacy, and future strategies. Rev. Infect. Dis. 10:560–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyle, F. T. 1990. Drug discovery: a chemist approach, pp.3–30. In J. F. Ryley (ed.), Chemotherapy of fungal infections. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 12.Contreras, L. M., J. Vivas, and J. A. Urbina. 1997. Altered lipid composition and enzyme activities of plasma membranes from Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi epimastigotes grown in the presence of sterol biosynthesis inhibitors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 53:697–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cushion, M. T., A. Harmsen, Y. Matsumoto, J. R. Springer, A. E. Wakefield, and M. Yamada. 1994. Recent advances in the biology of Pneumocystis carinii. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 32:217–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cuzner, M. L., and A. N. Davison. 1967. Quantitative thin layer chromatography of lipids. J. Chromatogr. 27:388–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson, R. N., S. L. Croft, A. Scott, M. Maini, A. H. Moody, and A. D. M. Bryceson. 1991. Liposomal amphotericin B in drug-resistant visceral leishmaniasis. Lancet 337:1061–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Docampo, R., and S. N. J. Moreno. 1999. Acidocalcisome: a novel Ca2+ storage compartment in trypanosomatids and apicomplexan parasites. Parasitol. Today 15:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goad, L. J., G. G. Holz, Jr., and D. H. Beach. 1984. Sterols of Leishmania species. Implications for biosynthesis. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 10:161–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haughan, P. A., M. L. Chance, and L. J. Goad. 1995. Effects of an azasterol inhibitor of 24-transmethylation on sterol biosynthesis and growth of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Biochem. J. 308:31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heeres, J., L. J. J. Backx, J. H. Mostmans, and J. V. Cutsem. 1979. Antimycotic imidazoles. Part 4. Synthesis and antifungal properties of ketoconazole, a new potent orally active broad-spectrum antifungal agent. J. Med. Chemother. 22:1003–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hessler, D., S. J. Young, B. O. Carragher, M. Martone, J. E. Hinshaw, R. A. Milligan, E. Masliah, M. Whitaker, S. Lamont, and M. H. Ellisman. 1992. Programs for visualization in three-dimensional microscopy. Neuroimage 1:55–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazardi, K., J. A. Urbina, and W. de Souza. 1990. Ultrastructural alterations induced by two ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors, ketoconazole and terbinafine, on epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2097–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazardi, K., J. A. Urbina, and W. de Souza. 1991. Ultrastructural alterations induced by ICI 195,739, a bis-triazole derivate with strong antiproliferative action against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:736–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liendo, A., G. Visbal, M. M. Piras, R. Piras, and J. A. Urbina. 1998. Sterol composition and biosynthesis in Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 104:81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macadan, R. F., and J. Williamson. 1974. Drug effects on the fine structure of Trypanosoma rhodesiense: suramim, tryparsamide and mapharside. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 68:301–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marsden, P. D. 1985. Pentavalent antimonials: old drugs for new diseases. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 18:187–198. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marsden, P. D., and T. C. Jones. 1985. Clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis, p. 183–198. In K. P. Chang and R. S. Bray (ed.), Human parasitic diseases, vol. 1. Leishmaniasis. Elsevier Science Publishers, New York, N.Y.

- 27.Masur, H. 1992. Prevention and treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 327:1853–1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercer, E. I. 1993. Inhibitors of sterol biosynthesis and their applications. Progr. Lipd. Res. 32:357–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miranda, K., M. Benchimol, R. Docampo, and W. de Souza. 2000. The fine structure of acidocalcisomes in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol. Res. 86:373–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Navin, T. R., B. A. Arana, J. D. Berman, and J. F. Chafon. 1992. Placebo-controlled clinical trial of sodium stibogluconate (Pentostan) versus ketoconazole for treating cutaneous leishmaniasis in Guatemala. J. Infect. Dis. 165:528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oehlschlager, A. C., and E. Czyzewska. 1992. Rationally designed inhibitors of sterol biosynthesis, p.437–475. In J. Sutcliffe and N. H. Georgopapadakou (ed.), Emerging targets in antibacterial and antifungal chemotherapy. Chapman & Hall, New York, N.Y.

- 32.Olliaro, P. L., and A. D. M. Bryceson. 1993. Practical progress and new drugs for changing patterns of leishmaniasis. Parasitol. Today 9:323–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan, A. A., S. M. Duboise, S. Eperon, L. Rivas, V. Hodgkinson, Y. Traub-Cseko, and D. Mcmahon-Pratt. 1993. Developmental life cycle of Leishmania—cultivation and characterization of cultured extracellular amastigotes. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 40:213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrany, G., N. S. Ryder, and A. Stutz. 1984. Allylamine derivates: new class of synthetic antifungal agents inhibiting fungal squalene epoxidase. Science 224:1239–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pimenta, P. F. P., and W. de Souza. 1985. Fine structure and cytochemistry of the endoplasmic reticulum and its association with the plasma membrane of Leishmania mexicana amazonensis. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. 17:413–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahur, A., M. Taton, and P. Benveniste. 1990. Inhibition of sterol biosynthesis in higher plants by analogues of high energy carbocationic intermediates, p.206–221. In P. J. Kuhn, A. P. J. Trinci, M. J. Jung, M. W. Goosey, and L. G. Copping (ed.), Biochemistry of cell walls and membranes in fungi. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 37.Rangel, H., F. Dager, A. Hernandez, A. Liendo, and J. A. Urbina. 1996. Naturally azole-resistant Leishmania braziliensis promastigotes are rendered susceptible in the presence of terbinafine. A comparative study with azole-susceptible Leishmania mexicana. Antmicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2785–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robson, G. D., M. Wiebe, P. J. Kuhn, and A. P. J. Trinci. 1990. Inhibitors of phospholipid biosynthesis, p.261–281. In P. J. Kuhn, A. P. J. Trinci, M. J. Jung, M. W. Goosey, and L. G. Copping (ed.), Biochemistry of cell walls and membranes in fungi. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Germany.

- 39.Rodrigues, C. O., R. Catisti, S. A. Uyemura, A. E. Vercesi, R. Lira, C. Rodriguez, J. A. Urbina, and R. Docampo. 2001. The sterol composition of Trypanosoma cruzi changes after growth in different culture media and results in different sensitivity to digitonin permeabilization. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 48:588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ryder, N. S., G. Seidl, and P. F. Troke. 1984. Effect of the antimycotic drug naftifine on growth and sterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 25:483–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryder, N. S. 1985. Specific inhibition of fungal steroid biosynthesis by SF-86327, a new allylamine antimycotic agent. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27:252–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryder, N. S. 1985. Effect of allylamine antimycotic agents on sterol biosynthesis measured by sterol side-chain methylation. J. Gen. Microbiol. 131:1595–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryder, N. S., and M. Dupont. 1985. Inhibition of squalene epoxidase by allylamine antimycotic compounds. A comparative study of the fungal and mammalian enzymes. Biochem. J. 230:765–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryder, N. S. 1988. Mechanism of action and biochemical selectivity of allylamine antimycotic agents. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 544:208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smulian, A. G., and P. D. Walzer. 1992. The biology of Pneumocystis carinii. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 18:191–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soares, M. J., and W. de Souza. 1991. Endocytosis of gold-labeled proteins and LDL by Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitol. Res. 77:461–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sud, I. J. S., and D. S. Feingold. 1981. Mechanism of action of antimycotic imidazoles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 76:438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sud, I. J. S., and D. S. Feingold. 1981. Heterogeneity of action mechanisms among antimycotic imidazoles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 20:71–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Troke, P. F., M. S. Marriot, K. Richardson, and M. H. Tarbit. 1988. In vitro potency and in vivo activity of azoles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 544:284–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Urbina, J. A., K. Lazardi, T. Aguire, M. M. Piras, and R. Piras. 1988. Antiproliferative synergism of the allylamine SF 86-327 and ketoconazole on epimastigotes and amastigotes of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1237–1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Urbina, J. A., S. Pekerar, H. B. Le, J. Patterson, B. Montez, and E. Oldfield. 1995. Molecular order and dynamics of phosphatidylcholine bilayer membranes in the presence of cholesterol, ergosterol and lanosterol—a comparative study using 2H-, 13C- and 31P-NMR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1238:163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Urbina, J. A., J. Vivas, G. Visbal, and L. M. Contreras. 1995. Modification of the sterol composition of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi epimastigotes by Δ24(25)-sterol methyltransferase inhibitors and their combinations with ketoconazole. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 73:199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urbina, J. A., J. Vivas, K. Lazardi, J. Molina, G. Payares, M. M. Piras, and R. Piras. 1996. Antiproliferative effects of Δ24(25)-sterol methyltransferase inhibitors on Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Chemotherapy (Tokyo) 42:294–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urbina, J. A. 1997. Lipid biosynthesis pathways as chemotherapeutic targets in kinetoplastid parasites. Parasitology 114:S91–S99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Urbina, J. A., G. Visbal, L. M. Contreras, G. Mclaughlin, and R. Docampo. 1997. Inhibitors of Δ24(25)-sterol methyltransferase block sterol synthesis and cell proliferation in Pneumocystis carinii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1428–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van den Bossche, H., G. Willemsens, W. Cools, W. F. J. Lauwers, and L. Le Jeune. 1978. Biochemical effects of miconazole in fungi. II. Inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans. Chem. Biol. Interact. 21:59–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Bossche, H., G. Willemsens, W. Cools, F. Cornelissen, W. F. J. Lauwers, and J. V. Van Custrem. 1980. In vitro and in vivo effects of the antimycotic drug ketoconazole on sterol synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17:922–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van den Bossche, H., D. Bellens, W. Cools, J. Gorrens, P. Marechal, H. Verhoeven, G. Willimsens, D. De Coster, D. Beerens, C. C. Haelterman, M. C. Coene, W. Lauwers, and L. le Jeunes. 1986. Cytochrome P-450: target for itraconazole. Drug Dev. Res. 8:287–298. [Google Scholar]

- 59.van den Bossche, H., P. Marichal, J. Gorrens, H. Geerts, and P. A. J. Janssen. 1988. Basis for the search of new antifungal drugs. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 544:191–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vannier-Santos, M. A., A. Martiny, J. R. Meyer-Fernandes, and W. de Souza. 1995. Leishmanial protein kinase C modulates host cell infection via secreted acid phosphatase. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 67:112–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vannier-Santos, M. A., J. A. Urbina, A. Martiny, A. Neves, and W. de Souza. 1995. Alterations induced by the antifungal compounds ketoconazole and terbinafine in Leishmania. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 42:337–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vannier-Santos, M. A., A. Martiny, U. Lins, J. A. Urbina, V. M. Borges, and W. de Souza. 1999. Impairment of sterol biosynthesis leads to phosphorus and calcium accumulation in Leishmania acidocalcisomes. Microbiology 145:3213–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vivas, J., J. A. Urbina, and W. de Souza. 1996. Ultrastructural alterations in Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi induced by Δ24(25)-sterol methyltransferase inhibitors and their combinations with ketoconazole. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 7:235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Webster, P., and D. G. Russel. 1993. The flagellar pocket of trypanosomatids. Parasitol. Today 9:201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Werbovitz, K. A., S. M. B. Jeronimo, T. L. Macdonald, and R. D. Pearson. 1992. Treatment of leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 5:840–848. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Young, S. J., S. M. Royer, P. M. Groves, and J. C. Kinnamon. 1987. Three-dimensional reconstruction from serial micrographs using an IBM PC. J. Elec. Microsc. Tech. 6:207–215. [Google Scholar]