Abstract

The MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump possessed by Neisseria gonorrhoeae is very similar to the MexA-MexB-OprM efflux pump of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Because the antimicrobial resistance property afforded by the MexA-MexB-OprM efflux pump also requires the TonB protein, we asked whether a similar requirement exists for the gonococcal efflux pump. Unlike earlier studies with P. aeruginosa, we found that constitutive levels of gonococcal resistance to hydrophobic antimicrobial agents (i.e., Triton X-100 [TX-100]) did not require the TonB, ExbB, or ExbD protein. However, inducible levels of TX-100 resistance in gonococci had an absolute requirement for the TonB-ExbB-ExbD system, suggesting that such resistance in gonococci has an energy requirement above and beyond that required for constitutive pump activity.

The ability of gram-negative bacteria to resist the toxic actions of structurally diverse antimicrobial agents is often a result of the synergistic activity of the impermeability barrier imposed by the outer membrane (OM) and the energy-dependent efflux of those agents that pass the OM (21). The mtr operon of Neisseria gonorrhoeae (17) encodes an energy-dependent efflux pump constituted by the MtrC membrane fusion protein, the MtrD transporter protein, and the MtrE outer membrane channel protein (3, 5, 6, 14, 22). The MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump provides for export of structurally diverse antimicrobial hydrophobic agents (HAs) such as certain antibiotics, dyes, detergents (6), and antibacterial peptides (27). Expression of the mtrCDE operon is negatively regulated by the product of the mtrR gene, which is divergently transcribed (5, 15). Mutations in mtrR or in the intergenic region between mtrCDE and mtrR result in the enhanced resistance of gonococci to several HAs. Many of those HAs bathe mucosal surfaces and include bile salts, gonadal steroids, and antibacterial peptides (3, 7, 19, 20, 27, 31). We recently described (26) that the levels of HA resistance mediated by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE pump could be elevated by growth of gonococci in the presence of sublethal concentrations of the nonionic detergent Triton X-100 (TX-100) or the spermicide nonoxynol 9. This induction was independent of the MtrR protein but was dependent on MtrA, an AraC-like transcriptional activator protein.

The gonococcal mtrCDE-encoded efflux system is similar to other efflux pumps possessed by Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12, 16, 23). Interestingly, a tonB mutant of P. aeruginosa deficient in iron siderophore uptake was shown to be hypersusceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics, reminiscent of the phenotypes of mutants with defects in the mexAB-oprM antibiotic efflux operon (13, 32). This finding suggests that proteins other than those recognized as forming efflux pumps may be needed for export activity. The TonB-ExbB-ExbD complex has been identified in many gram-negative bacteria, and it probably represents a conserved mechanism for the transfer of energy from the proton motive force to high-affinity receptors within the OM (2, 11, 24). Among the TonB-dependent receptors are those for siderophores, host iron chelates, group B colicins, certain phages, and vitamin B12. They have in common a conserved short stretch of amino acids termed the TonB box (9, 24). Although TonB proteins are generally implicated in uptake or import processes across the OM, a TonB-like protein identified in Aeromonas hydrophila was shown to play a role in the export of the exotoxin aerolysin (8).

In the work described here, we investigated if the TonB-ExbB-ExbD system could be involved with the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump to provide gonococci with resistance to HAs in a manner reported for the MexA-MexB-OprM efflux pump of P. aeruginosa (32). We now report that a tonB-exbB-exbD deletion mutant of gonococcal strain FA19 was incapable of being induced to have high levels of HA resistance with sublethal concentrations of TX-100 but had the same constitutive level of susceptibility to HAs.

TonB-ExbB-ExbD is not required for constitutive HA resistance in gonococci.

Zhao et al. (32) demonstrated that a tonB mutation in P. aeruginosa leads to a phenotype of hypersensitivity to a wide variety of antibiotics that are exported by the MexA-MexB-OprM efflux pump. In order to investigate if the TonB system could be involved with the related MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump in gonococci, we constructed a tonB-exbB-exbD deletion mutant by transforming (3) wild-type strain FA19 (Table 1) with DNA extracted (18) from meningococcal strain IR3434. Strain IR3434 was constructed as follows: two DNA fragments, located upstream and downstream of the ton operon, were amplified by PCR with the following primers: TonB-DEL-A (5′-GGCTCGAGCGATATGGGGCAGGGGGTTCA-3′), TonB-DEL-B (5′-GCGAAGCTTGCGGGGGTTAAAATTCGTTCTT-3′), TonB-DEL-C (5′-ACAAAGCTTTAGAAGCCGCC-3′), and TonB-DEL-D (5′-GCGGATCCGGTCTCAGTGGGTATAGC-3′). Primers TonB-DEL-A and TonB-DEL-B were used to amplify a 426-bp DNA fragment (the left arm) encoding the first 10 codons of tonB. Primers TonB-DEL-C and TonB-DEL-D were used to amplify a 472-bp DNA fragment (the right arm) encoding the last 24 codons of exbD. The left and right arms were ligated together, creating a unique HindIII restriction site (pNVY1571). A spectinomycin (SPT) resistance cassette (4) was then inserted into the HindIII restriction site. The resulting fragment was then cloned into pBluescript SK(−) (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), creating pNVY1573. Plasmid pNVY1573 was linearized with XhoI and transformed into Neisseria meningitidis IR1072. SPT-resistant colonies were selected, and inactivation of the tonB-exbB-exbD operon was confirmed by Southern hybridization (data not shown). Genomic DNA was extracted from one transformant (IR3434) and was used to transform gonococcal strain FA19. The transformants were selected on gonococcal medium base (GCB) agar plates supplemented with 60 μg of SPT per ml. The insertion of the SPT resistance cassette in one transformant (strain CR7) was verified by PCR. CR7 could not use hemoglobin as a sole source of iron (data not shown), a property that is dependent on a functional TonB-ExbB-ExbD system (28).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in the present study

| Species and strain | Characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Meningococci | ||

| IR1072 | Wild type | 29 |

| IR2113 | IR1072 but tonB :: KAN | 29 |

| IR2500 | IR1072 but exbB :: KAN | This study |

| IR2502 | IR1072 but ΔexbD :: KAN | This study |

| IR3434 | IR1072 but ΔtonB exbB exbD :: SPT | This study |

| Gonococci | ||

| FA19 | Wild type | Kindly provided by P. F. Sparling |

| CR4 | FA19 but tonB :: KAN | This study |

| CR5 | FA19 butexbB :: KAN | This study |

| CR6 | FA19 but ΔexbD :: KAN | This study |

| CR7 | FA19 but ΔtonB exbB exbD :: SPT | This study |

| KH14 | FA19 but mtrD::KAN | 7 |

| KH15 | FA19 but mtrR-171 | 5 |

The susceptibilities of wild-type strain FA19 and its isogenic tonB-exbB-exbD deletion mutant CR7 to diverse HAs (erythromycin [ERY], polymyxin B [PB], and TX-100), known to be exported by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump (6), were tested. Both strains had the same levels of resistance to these HAs (Table 2), while a transformant (strain KH14) of strain FA19 harboring an insertionally inactivated mtrD gene (7) was hypersusceptible to these HAs. In order to test if the TonB system was required for high-level HA resistance due to overexpression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump, we transformed gonococcal strain KH15 (6) with genomic DNA from strain CR7 (FA19 ΔtonB exbB exbD :: SPT). KH15 is isogenic to FA19 but has a mutation (mtrR171) in the intergenic region between mtrCDE and mtrR that reduces mtrR gene transcription and enhances mtrCDE gene expression (5), resulting in constitutive high-level HA resistance. The level of TX-100 resistance of KH15 ΔtonB exbB exbD :: SPT was not decreased in comparison with that of its parental strain KH15 (MIC, >10,000 μg/ml) (Table 2). These results suggest that the tonB-exbB-exbD operon is not involved with the HA resistance afforded by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump when the pump is expressed at a constitutive low level (strain FA19) or high level (strain KH15).

TABLE 2.

Levels of HA resistance expressed by isogenic gonococci

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| TX-100 | ERY | PB | |

| FA19 | 150 | 0.25 | 100 |

| KH14 (FA19 mtrD::KAN) | 25 | 0.06 | 30 |

| CR7 (FA19 ΔtonB exbB exbD::SPT) | 150 | 0.25 | 100 |

| KH15 (FA19 mtrR171) | >10,000 | 5 | >250 |

| CR8 (KH15 ΔtonB exbB exbD::SPT) | >10,000 | 5 | >250 |

All values represent average results from at least three independent determinations.

TonB-ExbB-ExbD system is required for inducible HA resistance.

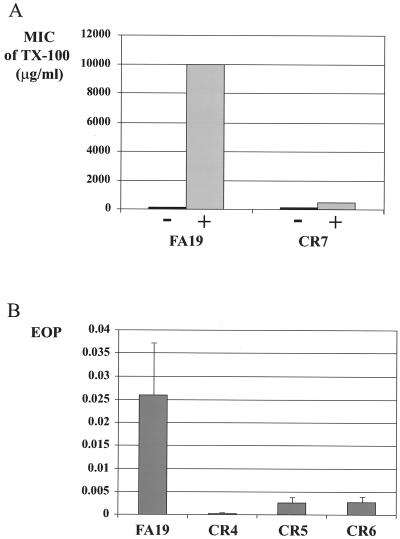

We previously demonstrated that the level of expression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump could be induced in strain FA19 by sublethal concentrations of TX-100 (26) to permit higher levels of resistance to TX-100. This induction process required the MtrA transcriptional activator and the MtrCDE efflux pump because transformants of strain FA19 bearing an insertional mutation in mtrC (6) or mtrD (i.e., strain KH14 used in the present study [data not shown]) were no longer inducible by TX-100. In order to determine if the TonB system could be involved in this induction, we examined the TX-100 resistance of wild-type strain FA19 and its isogenic mutant, CR7, from which tonB-exbB-exbD was deleted after overnight growth in the presence of 50 μg of TX-100 per ml. The presence of a sublethal concentration of this nonionic detergent enhanced the TX-100 resistance of parental strain FA19 by more than 66-fold. However, tonB-exbB-exbD mutant CR7 displayed only a slight increase in TX-100 resistance after growth under inducing conditions (Fig. 1A), suggesting that the TonB system is necessary for full induction of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump in N. gonorrhoeae. In order to verify that the level of resistance to TX-100 observed after induction was due to the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump, we evaluated the level of resistance to ERY, another HA exported by MtrC-MtrD-MtrE pump (6), after induction. We performed an efficiency-of-plating (EOP) experiment on GCB agar plates supplemented with 0.2 μg of ERY per ml after growth of strains FA19 and CR7 on GCB agar plates or on GCB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg of TX-100 per ml. The EOPs of both strains were equivalent without induction. However, after induction the EOP of strain FA19 was at least twofold higher than the EOP of strain CR7 (data not shown). These data confirm the previous results obtained with TX-100 that show that the resistance of strain CR7 is not fully inducible by a sublethal concentration of TX-100.

FIG. 1.

TX-100 resistance of FA19 and its isogenic tonB mutants. (A) MICs of TX-100 for gonococcal strains FA19 and CR7 (FA19 ΔtonB exbB exbD :: SPT) after overnight growth on GCB agar plates (−) or on GCB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg of TX-100 per ml (+). (B) EOPs of FA19, CR4 (FA19 without tonB-exbB-exbD), CR5 (FA19 without exbB-exbD), and CR6 (FA19 without exbD) on GCB agar plates supplemented with 200 μg of TX-100 per ml after growth overnight on GCB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg of TX-100 per ml. EOPs are average values from at least three independent determinations.

In order to evaluate the relative importance of each of the three proteins constituting the TonB-ExbB-ExbD system in gonococci, we constructed mutants of strain FA19 that lacked TonB-ExbB-ExbD, ExbB-ExbD, or ExbD. The donor DNAs were from meningococcal strains IR2113, IR2500, and IR2502 (Table 1) that have a polar kanamycin (KAN) cassette inserted into the tonB, exbB, and exbD genes, respectively. The construction of IR2113 has been described previously (29). Strains IR2500 and IR2502 were constructed as follows. Plasmid pIRS1137, which contains the 1.3-kb KSAC KAN resistance cassette (1) in the BclI site of the N. meningitidis exbB gene, was linearized with EcoRI and transformed into N. meningitidis IR1072, producing a chromosomal exbB mutant (strain IR2500). The StyI restriction fragment of pIRS1099, which encodes the C-terminal third of the ExbD protein, was replaced with the KAN resistance cassette from plasmid pKD102 (30), creating pIRS1236. pIRS1236, from which the exbD gene is deleted, was linearized with EcoRI and transformed into N. meningitidis IR1072, producing a chromosomal exbD mutant (strain IR2502). Inactivation of both genes was confirmed by Southern blotting hybridization (data not shown). Transformation of gonococcal strain FA19 with genomic DNA from meningococcal strains IR2113, IR2500, and IR2502 gave rise to strains CR4, CR5, and CR6, respectively. None of the mutants was able to use hemoglobin as a sole source of iron (data not shown). In order to detect minor differences in TX-100 susceptibility among these strains, we used the EOP assay to evaluate the antigonococcal action of TX-100. The EOPs of CR4 (tonB-exbB-exbD mutant), CR5 (exbB-exbD mutant), CR6 (exbD mutant), and isogenic parental strain FA19 were determined on GCB agar plates containing 200 μg of TX-100 per ml after growth overnight on GCB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg of TX-100 per ml. The results are presented in Fig. 1B. The EOP of parental strain FA19 was 0.026. In comparison, the EOPs of the mutant strains were dramatically decreased: 0.00017, 0.0022, and 0.0027 for strains CR4, CR5, and CR6, respectively. Thus, the mutation in strain CR5 that abrogated expression of the exbB and exbD genes resulted in a 10-fold decrease in the EOP, but an additional mutation in the tonB gene (strain CR4) led to a 150-fold decrease in the EOP on GCB agar plates supplemented with 200 μg of TX-100 per ml. These results suggest that the TonB protein may play a more significant role in the process of induction than the ExbB and ExbD proteins or that the exbB and exbD mutations can be partially complemented by genes encoding proteins with similar functions.

To provide evidence that the lack of increased TX-100 resistance after induction in CR7 was due to a lack of enhanced efflux mediated by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump, we performed an EOP analysis using ERY and crystal violet (CV), which are known substrates for the pump (6, 7, 5, 22). The EOPs of FA19 and CR7 were determined on GCB agar plates supplemented with 0.1 μg of ERY per ml or 1.5 μg of CV per ml after growth of the strains on GCB agar or GCB agar supplemented with 50 μg of TX-100 per ml. While the EOP assay of gonococcal strain FA19 showed a fourfold increase in ERY resistance and a twofold increase in CV resistance after induction, there was no measurable increase in the level of resistance to ERY or CV for CR7 (data not shown).

Iron availability does not influence TX-100 induction.

Because the TonB, ExbB, and ExbD proteins are involved with most bacterial iron uptake (2, 11, 25, 28), the likely consequence of a tonB-exbB-exbD mutation is iron deprivation of the bacterial cells. In order to investigate if iron deprivation could influence HA resistance mediated by the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump, we determined the MIC of TX-100 after overnight growth of strains FA19 and CR7 (FA19 ΔtonB exbB exbD) in the presence of the iron chelator desferoxamine mesylate (Desferal) at a concentration of 10 μM. We also added 10 μM desferoxamine mesylate to the GCB agar plates with TX-100 because the TX-100 induction of resistance in gonococci is a reversible phenomenon (C. Rouquette-Loughlin et al., unpublished results). Without TX-100 induction, the MICs of TX-100 in the presence of Desferal were the same (150 μg/ml) for both strains. This result suggests that iron availability does not regulate the constitutive expression of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump. In order to test if iron restriction could abolish the induction of resistance to TX-100, we then determined the MIC of TX-100 in the presence of Desferal after growing the strains in the presence of 50 μg of TX-100 per ml plus 10 μM Desferal late. The TX-100 resistance of FA19 was still inducible (MIC, 10,000 μg/ml), but the TX-100 resistance of CR7 could not be induced to similar levels (MIC, 200 μg/ml). These results indicated that the absence of induction of TX-100 resistance in CR7 was not a consequence of the iron restriction that could result from the tonB-exbB-exbD deletion. In order to confirm this result, we determined the MIC of TX-100 in the presence of an excess of iron [400 μM Fe(NO3)3] to verify that an excess of iron could not restore the inducibility of TX-100 resistance in CR7. We determined the MICs of TX-100 with or without induction by 50 μg of TX-100 per ml for strains FA19 and CR7. The resistance of strain CR7 remained mostly noninducible (MIC, 500 μg/ml), and the resistance of FA19 remained fully inducible (MIC, >10,000 μg/ml).

In order to confirm that strain FA19 was in a state of iron starvation when it was grown in the presence of 10 μM Desferal but not in the presence of 400 μM Fe(NO3)3, we prepared OM samples (25). The samples were solubilized and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (10). Visualization of the separated proteins by staining of the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue revealed the overexpression of certain proteins in the OM sample obtained from gonococci grown on GCB agar plates containing Desferal (data not shown). One of these proteins migrated with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 85,000 Da. Using a rabbit polyclonal serum against the B subunit of the neisserial hemoglobin receptor (HpuB), which is known to be an iron-repressible protein (28), we determined that this protein was overexpressed in strain FA19 when it was grown on agar containing Desferal and was present at significantly lower levels in the OM samples from gonococci when it was grown in the presence of added iron (400 μM) (data not presented). Hence, we concluded that our growth conditions involving the addition of 10 μM Desferal to the GCB agar resulted in the iron starvation of the gonococci. Taken together, these results suggested that iron availability did not interfere with the induction of TX-100 resistance in FA19 and that the TonB system could have a more direct role in the process of induction.

Unlike the MexA-MexB-OprM efflux pump in P. aeruginosa (32), the gonococcal MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump does not require the TonB system for constitutive low- or high-level resistance to antimicrobial agents. However, inducible levels of gonococcal resistance to HAs do require the TonB-ExbB-ExbD system. It is not clear why the TonB system is required only for inducible resistance to HAs mediated by MtrC-MtrD-MtrE, while the functionally similar efflux pump in P. aeruginosa requires TonB for constitutive activity. We could, however, envision two possibilities. First, during the induction process in gonococci, a TonB-dependent receptor for TX-100 becomes available that promotes its entry into the cell, an event essential for gene activation. In that case, a tonB-exbB-exbD deletion mutant would no longer be able to import TX-100 and the transcriptional activation mediated by MtrA (26) would not occur. An alternative hypothesis is one advanced originally by Zhao et al. (32): cytoplasmic membrane energy-coupling protein TonB may facilitate the channel opening of the OM protein of the efflux pump, i.e., OprM in P. aeruginosa and MtrE in N. gonorrhoeae. However, this would mean that the mechanism of channel opening is different in gonococci during constitutive and inducible efflux pump activity. Further studies are necessary to determine the physiologic events involved in the induction of the MtrC-MtrD-MtrE efflux pump.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by PHS grants AI-21150 (to W.M.S.), AI-37945 (to W.M.S.), and AI-472870 (to I.S.) from NIH. W. M. Shafer is the recipient of a Senior Research Career Scientist Award from the Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barany, F. 1985. Single-stranded hexameric linkers: a system for in-phase insertion mutagenesis and protein engineering. Gene 37:111–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biswas, G. D., J. E. Anderson, and P. F. Sparling. 1997. Cloning and functional characterization of Neisseria gonorrhoeae tonB, exbB and exbD genes. Mol. Microbiol. 24:169–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delahay, R. M., B. D. Robertson, J. T. Balthazar, W. M. Shafer, and C. A. Ison. 1997. Involvement of the gonococcal MtrE protein in the resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to toxic hydrophobic agents. Microbiology 143:2127–2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frey, J., and H. M. Krisch. 1985. Omega mutagenesis in gram-negative bacteria: an electable interposon which is strongly polar in a wide range of bacterial species. Gene 36:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagman, K. E., and W. M. Shafer. 1995. Transcriptional control of the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 171:4162–4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagman, K. E., W. Pan, B. G. Spratt, J. T. Balthazar, R. C. Judd, and W. M. Shafer. 1995. Resistance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to antimicrobial hydrophobic agents is modulated by the mtrRCDE efflux system. Microbiology 141:611–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagman, K. E., C. E. Lucas, J. T. Balthazar, L. A. Snyder, M. Nilles, R. C. Judd, and W. M. Shafer. 1997. The MtrD protein of Neisseria gonorrhoeae is a member of the resistance/nodulation/division protein family constituting part of an efflux system. Microbiology 143:2117–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howard, S. P., H. G. Meiklejohn, D. Shivak, and R. Jahagirdar. 1996. A TonB-like protein and a novel membrane protein containing an ATP-binding cassette function together in exotoxin secretion. Mol. Microbiol. 22:595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadner, R. J. 1990. Vitamin B12 transport in Escherichia coli. Energy coupling between membranes. Mol. Microbiol. 4:2027–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen, R. A., P. S. Myers, J. T. Skare, C. L. Seachord, R. P. Darveau, and K. Postle. 1996. Identification of TonB homologues in the family Enterobacteriaceae and evidence for conservation of TonB-dependent energy transduction complexes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1363–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, X.-Z., H. Nikaido, and K. Poole. 1995. Role of MexA-MexB-OprM in antibiotic efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1948–1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, X.-Z., and K. Poole. 2001. Mutational analysis of the OprM outer membrane component of the MexA-MexB-OprM multidrug efflux system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 183:12–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lucas, C. E., K. E. Hagman, J. C. Levin, D. C. Stein, and W. M. Shafer. 1995. Importance of lipooligosaccharide structure in determining gonococcal resistance to hydrophobic antimicrobial agents resulting from the mtr efflux system. Mol. Microbiol. 16:1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lucas, C. E., J. T. Balthazar, K. E. Hagman, and W. M. Shafer. 1997. The MtrR repressor binds the DNA sequence between the mtrR and mtrC genes of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Bacteriol. 179:4123–4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma, D., D. N. Cook, M. Alberti, H. Nikaido, and J. E. Hearst. 1993. Molecular cloning of the acrA and acrE genes of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 175:6299–6313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maness, M. J., and P. F. Sparling. 1973. Multiple antibiotic resistance due to a single mutation in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J. Infect. Dis. 128:321–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAllister, C. F., and D. S. Stephens. 1993. Analysis in Neisseria meningitidis and other Neisseria species of genes homologous to the FKBP immunophilin family. Mol. Microbiol. 10:13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morse, S. A., and P. G. Lysko. 1980. The cell envelope of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, p.1–6. In D. Daniellson and S. Normark (ed.), Genetics and immunobiology of pathogenic Neisseria. Norrlands-tryck I Umea, Umea, Sweden.

- 20.Morse, S. A., P. G. Lysko, L. McFarland, J. S. Knapp, E. Sandstrom, C. Critchlow, and K. K. Holmes. 1982. Gonococcal strains from homosexual men have outer membranes with induced permeability to hydrophobic molecules. Infect. Immun. 37:432–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikaido, H. 1994. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264:382–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan, W., and B. G. Spratt. 1994. Regulation of the permeability of the gonococcal cell envelope by the mtr system. Mol. Microbiol. 11:769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poole, K., K. Krebs, C. McNally, and S. Neshat. 1993. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: evidence for the involvement of an efflux system. J. Bacteriol. 175:7363–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Postle, K. 1993. TonB protein and energy transduction between membranes. J. Bioenerget. Biomembr. 25:591–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richardson, A. R., and I. Stojiljkovic. 1999. HmbR, a hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein of Neisseria meningitidis undergoes phase variation. J. Bacteriol. 181:2067–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouquette, C., J. B. Harmon, and W. M. Shafer. 1999. Induction of the mtrCDE-encoded efflux pump system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae requires MtrA, an AraC-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 33:651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shafer, W. M., X.-D. Qu, A. J. Waring, and R. I. Lehrer. 1998. Modulation of Neisseria gonorrhoeae susceptibility to vertebrate antibacterial peptides due to a member of the resistance/nodulation/division efflux pump family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:1829–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stojiljkovic, I., J. Larson, V. Hwa, S. Anic, and M. So. 1996. HmbR outer membrane receptors of pathogenic Neisseria spp.: iron-regulated, hemoglobin-binding proteins with a high level of primary structure conservation. J. Bacteriol. 178:4670–4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stojiljkovic, I., and, N. Shrinivasan. 1997. Neisseria meningitidis tonB, exbB, and exbD genes: Ton-dependent utilization of protein bound iron in neisseriae. J. Bacteriol. 179:805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trieu-Cuot, P., A. Klier, and P. Courvalin. 1985. DNA sequences specifying the transcription of the streptococcal kanamycin resistance gene in Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veal, W. L., A. Yellen, J. T. Balthazar, W. Pan, B. G. Spratt, and W. M. Shafer. 1998. Loss-of-function mutations in the mtr efflux system of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Microbiology 144:621–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao, Q., X.-Z. Li, A. Mistry, R. Srikumar, L. Zhang, O. Lomovskaya, and K. Poole. 1998. Influence of the TonB energy-coupling protein on efflux-mediated multidrug resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2225–2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]