Abstract

SS750 [(R)-(−)-2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-1-(ethylsulfonyl)-1,1-difluoro-3-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-2-propanol] is a new triazole, and its potential as an antifungal agent was evaluated by in vitro and in vivo studies. In a comparison of the MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited (MIC50s) for all strains of Candida species and Cryptococcus neoformans tested, SS750 was four times or more active than fluconazole and had activity comparable to that of itraconazole. The most important advantage of SS750 was that, when the MIC90s were compared, SS750 had 64 and 32 times greater antifungal activities than fluconazole against Candida krusei and Candida glabrata, respectively, which are intrinsically less susceptible to fluconazole. In cyclophosphamide-immunosuppressed mouse models of systemic and pulmonary candidiasis caused by C. albicans, oral SS750 prolonged the number of days of survival of infected animals in a dose-dependent manner and was 4 and ≥64 times more potent than fluconazole and itraconazole, respectively. In a safety profile, SS750, like fluconazole, had less of an affinity for binding to mammalian cytochrome P450 compared with that of ketoconazole, despite its strong affinity for binding to fungal cytochrome P450. The mechanism for the increased in vitro antifungal activity of SS750 against C. krusei is partially due to the potent inhibitory activity (3.7 times versus that of fluconazole) of C. krusei cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase; SS750 showed a strong affinity for binding to cytochrome P450 of C. krusei, indicating that SS750 acts by inhibiting the cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase of fungal cells.

The incidence of opportunistic fungal infections has been increasing worldwide, especially due to the increase in the number of hosts immunocompromised because of cancer chemotherapy, organ and bone marrow transplantation, and human immunodeficiency virus infection (3, 8, 17, 24). Fluconazole (FLC) has been used with considerable success in the treatment of serious fungal infections caused by Candida albicans, a major opportunistic pathogen (7).

However, extensive use of FLC has led to increases in the numbers of FLC-resistant C. albicans isolates causing oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals and the numbers of non-C. albicans species that are less susceptible to FLC, such as Candida glabrata and Candida krusei (20). Moreover, although itraconazole (ITC) is also available as an alternative for such patients, its unpredictable lower concentration in plasma due to its highly hydrophobic nature has caused therapeutic failures in some cases (9, 19). Amphotericin B (AMB) remains the “gold standard” drug for life-threatening fungal infections, but its use is limited due to its severe toxicity and the inconvenience of intravenous dosing (18, 21).

Keeping these risk factors, adverse effects, and inconveniences in mind, we have attempted to develop new antifungal agents. In general, the azole compound is much less toxic than polyene antibiotics, e.g., AMB. Specifically, we have devoted attention to the azole compound, an ergosterol synthesis inhibitor, as a target for development.

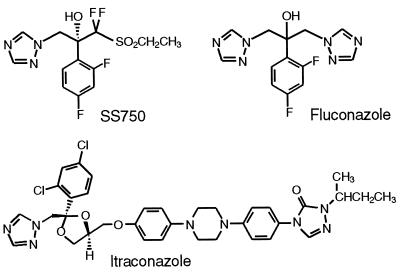

In order to enhance the in vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of this compound against pathogenic fungi, including strains less susceptible to FLC, we introduced fluorine atoms into antifungal triazoles; our research focused on discovering new azoles with a gem-difluoromethylene moiety (2). The introduction of fluorine into an organic molecule causes dramatic changes in biological activity, mainly because of the high electronegativity of fluorine, the strong carbon-fluorine bond, and the increased lipid solubility because of its relatively low molecular weight. We selected SS750 among various candidates for further evaluation because of its strong antifungal activity and lower level of toxicity (Fig. 1). It is strongly suggested that the ethylsulfonyl gem-difluoromethylene moiety in this molecule, coupled with its improved hydrophobic property compared with that of FLC, leads to increased antifungal activities against pathogenic fungi (S. Takeda, Y. Kaneko, M. Tokizawa, H. Eto, and S. Sato, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1080, p. 198, 2000).

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of three triazole derivatives (SS750, FLC, and ITC).

Furthermore, in comparison to FLC, SS750 has a broader antifungal spectrum and much stronger activity against pathogenic fungi, including filamentous fungi (K. Yokoyama, L. Wang, H. Kaji, J. Ito, M. Matsumoto, K. Kamei, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1084, p. 199, 2000).

In the present study, we evaluated the in vitro antifungal activity of SS750 against Candida species and Cryptococcus neoformans, its oral efficacy against candidiasis in mice, its effect on ergosterol biosynthesis, and its affinity of binding to cytochrome P450.

(This work was presented in part at the 40th Interscience. Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 17 to 20 September 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

SS750 [(R)-(−)-2-(2,4-difluorophenyl)-1-(ethylsulfonyl)-1,1-difluoro-3-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)-2-propanol] was synthesized at SSP Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. FLC and ITC were purchased from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Inc., Tokyo, Japan, and Janssen-Kyowa Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, respectively. AMB and ketoconazole (KTC) were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. [2-14C]mevalonic acid dibenzylethylenediamine salt (specific activity, 66.0 mCi/mmol) was purchased from Nycomed Amersham plc (Amersham, United Kingdom).

Fungus strains.

Most of the strains used in the present study were obtained from the Research Center for Pathogenic Fungi and Microbial Toxicoses, Chiba University, Chiba, Japan, and other suppliers. C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. krusei ATCC 6258 were also obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.).

In vitro antifungal activity.

The MICs of SS750 and the generally proven reference drugs FLC, ITC, and AMB for Candida species and C. neoformans were determined by a broth microdilution method according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) method M27-A (14). SS750 was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The strains were cultured at 35°C for 46 to 50 h. The MICs were read spectrophotometrically (Microplate Reader M-Vmax; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The MICs of SS750, FLC, and ITC were defined as the lowest concentration at which there was 80% inhibition of growth compared with the growth of a drug-free control; the MIC of AMB was defined as the lowest concentration at which there was 100% inhibition of growth.

Therapeutic effects on systemic and pulmonary candidiasis in immunosuppressed mice.

C. albicans IFM 40009 was grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C for 24 h and was prepared with sterile saline at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells/ml for systemic infection and 1 × 108 cells/ml for pulmonary infection. Five-week-old male ICR mice (weight, 22 to 26 g; Charles River Japan, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan) were used (10 mice per group). They were housed in cages of 10 per group and had access to food and water ad libitum. This study keenly respected established guidelines (6). For immunosuppression, cyclophosphamide (Endoxan; Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was administered intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 mg/kg of body weight per day on day 4 and day 1 before infection, on day 3 after infection, and every 4th day thereafter. Two-tenths milliliter (105 CFU) of the fungal suspension was injected into the tail vein for systemic infection. For the pulmonary infection study, 50 μl (5 × 106 CFU) of the fungal suspension was intranasally inoculated after the animals were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (Veterinary Ketalar 50; Sankyo Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at 20 mg/kg intravenously. SS750 and the triazole derivatives of FLC and ITC were orally administered once a day for 4 consecutive days, starting at 1 h after infection. The desired drug dose was given in a volume of 0.1 ml per 10 g of body weight. Fasting took place for 5 h before the first administration. As a solvent for SS750 and FLC, 0.5% carboxymethyl cellulose-sodium was used, and for ITC, 40% (wt/vol) hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Funakoshi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used by a method slightly modified from that reported previously (13). The infection control group was untreated. The animals were observed for survival or death for 21 days after infection. The duration of survival was determined by the Kaplan-Meier technique and was analyzed by the log rank test. Each series of experiments was performed at least in duplicate to ensure the consistency of the results.

Cell-free ergosterol biosynthesis assay.

In order to study the inhibitory effects of SS750, FLC, and ITC on cell-free ergosterol biosynthesis, C. albicans ATCC 90028 (a reference strain according to NCCLS guidelines [14]) and C. krusei ATCC 6258 (a quality control strain according to NCCLS guidelines [14]) were used. Crude enzyme was prepared, and sterol biosynthesis was measured by methods similar to those reported previously (5, 12, 16). Each strain was cultured at 30°C for 13 h in YPG broth (1% Bacto Peptone, 1% yeast extract, 4% glucose) under conditions of shaking at 110 or 90 rpm. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C and were washed twice with cold distilled water and suspended in cold buffer A (100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7.4], 30 nM nicotinamide, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM reduced glutathione). The cells were mixed with an equal volume of glass beads (diameter, 0.45 to 0.5 mm) and were homogenized with a cell homogenizer (Braun GmbH, Mesungen, Germany) operating at 4,000 rpm with nine 10-s bursts and intervals of 30 s with liquid carbon dioxide cooling (1). The cell debris and glass beads were removed by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants were centrifuged twice at 10,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C, and the cell-free supernatants were stored at −80°C before use. The protein concentration was quantified by the method of Lowry et al. (10). The cell-free supernatants were diluted with buffer A at 11.4 mg of protein/ml; MgCl2 and MnCl2 (61.0 and 39.6 mg/ml, respectively, in distilled water) were added at 10 μl/ml. This mixture was used as the crude enzyme extract. The reaction mixture consisted of crude enzyme extract (880 μl), a solution of an antifungal drug dissolved in DMSO (10 μl), [2-14C]mevalonate (10 μl, 0.25 μCi), and cofactor solution (100 μl containing 6 μM ATP, 3 μM glucose-6-phosphate, 1 μM NADPH, and 1 μM NAD in 1 mM potassium phosphate buffer [pH 7.4]). The mixture was incubated at 30°C for 30 min with shaking (100 rpm). The reaction was then stopped by adding 1 ml of freshly prepared saponification reagent (15% [wt/vol] KOH in 90% [vol/vol] ethanol); the mixture was heated at 80°C for 1 h for saponification. Nonsaponifiable lipids (sterols and sterol precursors) were extracted twice with 2 ml of n-heptane and were dried under nitrogen at 40°C. The nonsaponifiable lipid was applied to silica gel 60-precoated thin-layer chromatography plates (Merck Co., Ltd.), and the plates were developed with n-heptane, diisopropylether, acetic acid, and ethyl acetate (60:40:4:34.7; vol/vol). Radioactive metabolite zones were located and quantified with a BAS 2000 imaging analyzer (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo, Japan).

Affinity of binding to microsomal cytochrome P450.

We compared the affinities of binding of SS750, FLC, and ITC to microsomal cytochrome P450 in C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. krusei ATCC 6258. KTC, an imidazole derivative, was additionally used in a comparison of affinities of binding to microsomal cytochrome P450 in rat and human liver. Rat and human liver microsomal fractions were purchased from Charles River Japan, Inc., Kanagawa, Japan, and from Gentest Co., Woburn, Mass., respectively. Fungus microsomal fractions were prepared by methods similar to those reported previously (5, 22). Each test strain was precultured in YPG broth medium (1% yeast extract, 1% Bacto Peptone, 2% glucose) at 30°C for 16 h and inoculated and cultured in 4% glucose-containing YPG broth medium at 30°C for 13 h under agitation at 110 rpm. Cells in the logarithmic phase were obtained. These cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min; washed with distilled water; suspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM disodium EDTA, and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Then, Zymolyase-20T (15 mg per 1 g [wet weight] of cells; Seikagaku Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was added and the suspension was gently stirred at 30°C for 90 min. The spheroplasts were harvested by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min. After being washed with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 1.2 M sorbitol and 10 mM disodium EDTA, the spheroplasts were suspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mM disodium EDTA and 0.1 mM reduced glutathione. This spheroplast suspension was homogenized in a glass homogenizer and was centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 5 min to remove debris and unbroken spheroplasts. The supernatant was centrifuged twice at 10,000 × g for 20 min, followed by centrifugation at 105,000 × g for 90 min to produce a pellet. The pellet was suspended in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) containing 20% (vol/vol) glycerol and was stored at −80°C until use. The cytochrome P450 contents in all microsomal fractions were measured and were calculated by a previously reported method (15) as the difference in the absorbance between 448 nm (C. albicans and C. krusei) or 450 nm (rat and human) and 490 nm from that for the control. Each microsomal suspension was diluted with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) so that the cytochrome P450 concentration was 0.15 nM per ml. An antifungal drug solution of 2.2 μl in DMSO was added to a 1.5-ml tube containing 550 μl of the microsomal suspension, and the tube was incubated at 37°C for 10 min (final DMSO concentration, 0.4%). The suspensions reduced with sodium hydrosulfite were transferred to semimicro quartz cells. Carbon monoxide was used to aerate the suspensions for 30 s. One minute later, the absorption spectrum from 550 to 360 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer (DU 640; Beckman Instruments Inc., Fullerton, Calif.). The differences in the absorbance between 448 nm (C. albicans and C. krusei) or 450 nm (rat and human) and 490 nm were compared.

RESULTS

In vitro antifungal activity.

The MICs of SS750, FLC, ITC, and AMB for Candida species and C. neoformans, most of which were isolated clinically, are shown in Table 1. The data are presented as MIC ranges, the MICs at which 50% of isolates are inhibited (MIC50s), and MIC90s. The MIC90 of SS750 for 55 strains of C. albicans was 0.125 μg/ml, which was four times greater than those of FLC and AMB and two times less than that of ITC. On the basis of the NCCLS breakpoints for the FLC resistance of C. albicans, involving multiefflux mechanisms, the MICs of SS750, FLC, and ITC were >16, >64, and >8 μg/ml, respectively, for two resistant strains (data not shown). SS750 showed cross-resistance and might be a substrate for an efflux pump for these two strains. The MIC50 and MIC90 of SS750 for FLC-resistant C. albicans including resistant and dose-dependent susceptible strains were 1 and >16 μg/ml, respectively. In a comparison of the MIC50s, SS750 was 32 times more potent than FLC and 2 times less potent than ITC and AMB. The MIC90s of SS750 for Candida parapsilosis, C. krusei, and C. glabrata, i.e., Candida species less susceptible to FLC, were 0.25, 1, and 2 μg/ml, respectively. SS750 was 32 to 64 times more potent than FLC and had potency comparable to or slightly less than that of ITC; the performance of SS750 was comparable to that of AMB. SS750 showed better activities against Candida tropicalis, Candida guilliermondii, Candida kefyr, and C. neoformans, with an MIC90 range of 0.063 to 2 μg/ml. SS750 was four to eight times more active than FLC and was slightly less active than ITC. The performance of SS750 was comparable to that of AMB. Moreover, the MIC50s of SS750 for Candida species and C. neoformans ranged from 0.031 to 1 μg/ml. In a comparison of the MIC50s, SS750 was four or more times more potent than FLC and had potency comparable to those of ITC and AMB.

TABLE 1.

MICs of SS750, FLC, ITC, and AMB for Candida species and C. neoformansa

| Organism (no. of strains) and drug | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 50% | 90% | |

| C. albicans (55) | |||

| SS750 | 0.031–0.25 | 0.063 | 0.125 |

| FLC | 0.125–2 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| ITC | ≤0.008–0.125 | 0.031 | 0.063 |

| AMB | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Fluconazole-resistant C. albicans (6)b | |||

| SS750 | 0.5–>16 | 1 | >16 |

| FLC | 16–>64 | 32 | >64 |

| ITC | 0.5–>8 | 0.5 | >8 |

| AMB | 0.5–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| C. tropicalis (17) | |||

| SS750 | 0.031–0.5 | 0.063 | 0.5 |

| FLC | 0.25–4 | 1 | 2 |

| ITC | 0.016–0.25 | 0.063 | 0.125 |

| AMB | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| C. parapsilosis (15) | |||

| SS750 | ≤0.016–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| FLC | 0.25–8 | 2 | 8 |

| ITC | 0.016–0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| AMB | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 |

| C. guilliermondii (14) | |||

| SS750 | ≤0.016–1 | 0.125 | 1 |

| FLC | 0.25–8 | 4 | 4 |

| ITC | 0.016–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| AMB | 0.125–1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| C. kefyr (9) | |||

| SS750 | 0.031–0.063 | 0.031 | 0.063 |

| FLC | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| ITC | 0.016–0.25 | 0.063 | 0.25 |

| AMB | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| C. krusei (16) | |||

| SS750 | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

| FLC | 16–>64 | 64 | 64 |

| ITC | 0.063–0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| AMB | 0.5–1 | 1 | 1 |

| C. glabrata (14) | |||

| SS750 | 0.063–4 | 1 | 2 |

| FLC | 0.5–64 | 16 | 64 |

| ITC | 0.031–4 | 1 | 4 |

| AMB | 0.125–0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| C. neoformans (26) | |||

| SS750 | 0.125–2 | 0.5 | 2 |

| FLC | 1–16 | 4 | 8 |

| ITC | 0.031–0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| AMB | 0.25–1 | 0.5 | 1 |

MICs were determined by the broth microdilution method according to NCCLS method M27-A (14).

Three resistant and three dose-dependent susceptible strains, on the basis of NCCLS breakpoints for FLC resistance in C. albicans, were included.

Therapeutic effects against systemic and pulmonary candidiasis in immunosuppressed mice.

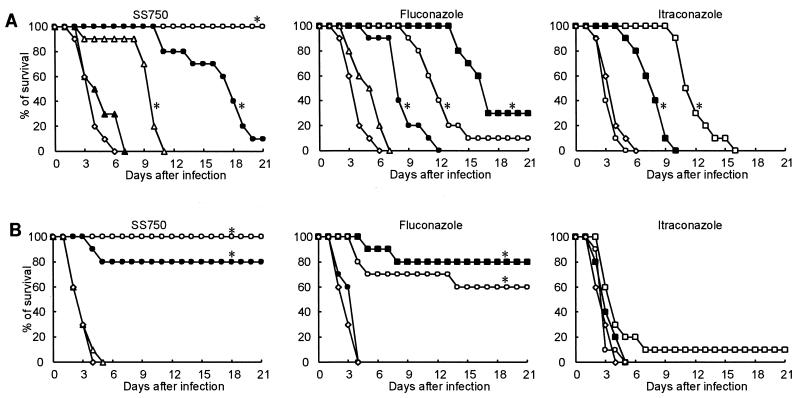

The therapeutic effects of SS750, FLC, and ITC against systemic and pulmonary candidiasis caused by C. albicans IFM 40009 in immunosuppressed mice after oral administration for 4 consecutive days are shown in Fig. 2. SS750, FLC, and ITC prolonged the number of days of survival in animals with systemic and pulmonary candidiasis in a dose-dependent manner. SS750 at doses of 0.25 and 1 mg/kg of body weight per day in animals with systemic and pulmonary candidiasis, respectively, significantly prolonged the number of days of survival compared with those for the animals in the untreated control group (P < 0.01). When the substances were compared according to the minimum dose necessary to yield significantly prolonged survival, SS750 was 4 and 64 times more potent against systemic candidiasis than FLC and ITC, respectively, and was also 4 and >64 times more potent against pulmonary candidiasis than FLC and ITC, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Therapeutic effects of SS750, FLC, and ITC against systemic (A) and pulmonary (B) candidiasis caused by C. albicans IFM 40009 in immunosuppressed mice. The MICs for the infectious strain were 0.063 μg/ml for SS750, 0.025 μg/ml for FLC, and 0.031 μg/ml for ITC. SS750 and the reference drugs were orally administered to 10 animals per group once daily for 4 consecutive days, starting at 1 h after infection. Symbols: □, 64 mg/kg; ▪, 16 mg/kg; ○, 4 mg/kg; •, 1 mg/kg; ▵, 0.25 mg/kg; ▴, 0.063 mg/kg; ◊, untreated control; *, significantly different from the survival of untreated controls (P < 0.01 by the Kaplan-Meier technique and the log rank test).

Inhibitory effects on cell-free ergosterol biosynthesis.

The inhibitory effects of SS750, FLC, and ITC on ergosterol biosynthesis in cell extracts and their activities on the inhibition of growth of C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. krusei ATCC 6258 are listed in Table 2. SS750, FLC, and ITC inhibited the incorporation of [14C]mevalonate into the ergosterols of C. albicans and C. krusei at concentrations less than their MICs. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of SS750 for ergosterol biosynthesis in cell extracts and the MIC of SS750 for C. albicans were 0.019 and 0.17 μM, respectively. For C. albicans, the inhibitory effect of SS750 on ergosterol biosynthesis in cell extracts was 1.5 times stronger than that observed with FLC, and it was identical to that observed with ITC; the antifungal activity of SS750 was 4.8 times stronger than that observed for FLC but was 4.3 times less than that observed for ITC. SS750 also inhibited ergosterol synthesis in cell extracts, with an IC50 of 0.21 μM, and at 1.36 μM it inhibited the growth of C. krusei. For C. krusei, the inhibitory effect of SS750 on ergosterol biosynthesis in cell extracts was 3.7 times stronger than that observed for FLC, and it was identical to that observed for ITC; the SS750 MIC was 76.8 times lower than that of FLC but was 3.9 times higher than that of ITC.

TABLE 2.

IC50s and MICs of SS750, FLC, and ITC for C. albicans and C. krusei

| Strain and drug | IC50 (μM)a | MIC (μM)b |

|---|---|---|

| C. albicans ATCC 90028 | ||

| SS750 | 0.019 | 0.17 |

| FLC | 0.028c | 0.82 |

| ITC | 0.019 | 0.04 |

| C. krusei ATCC 6258 | ||

| SS750 | 0.21 | 1.36 |

| FLC | 0.78d | 104.5 |

| ITC | 0.21 | 0.35 |

IC50s were the concentrations needed to inhibit ergosterol synthesis from [14C]mevalonate by 50% in cell extracts of C. albicans ATCC 90028 and C. krusei ATCC 6258. Results are the means of three experiments. Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used to compare the IC50s obtained in the three experiments.

MICs were determined by the broth microdilution method according to NCCLS method M27-A (14).

P < 0.05. versus the IC50s of SS750 and ITC.

P < 0.01 versus the IC50s of SS750 and ITC.

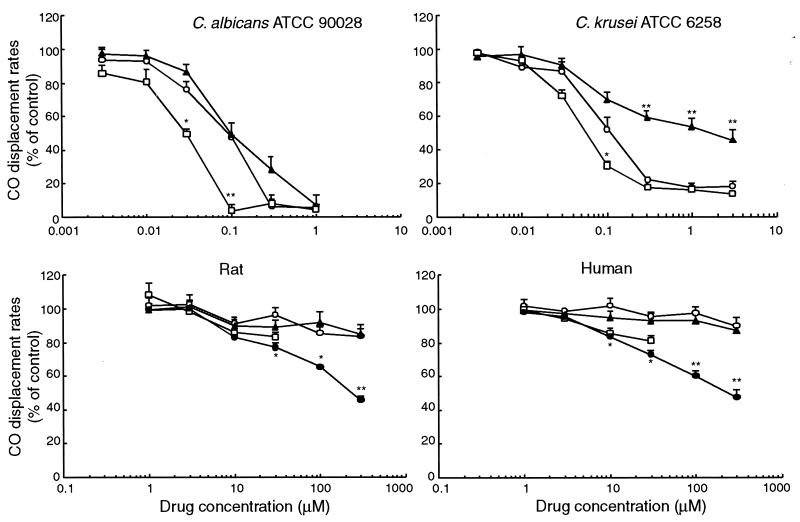

Affinity of binding to microsomal cytochrome P450.

The affinities of binding of SS750 and reference drugs, shown by CO displacement rates, to fungal and mammalian microsomal cytochrome P450s are presented in Fig. 3. SS750, FLC, and ITC inhibited CO and cytochrome P450 (CO-P450) complex formation in samples from C. albicans and C. krusei cultures in a dose-dependent manner. The CO displacement rates of SS750 at 0.1 and 0.3 μM for C. albicans cytochrome P450 were 47.8 and 6.7%, respectively. The binding affinities of SS750 were similar to those of FLC at 0.1 and 0.3 μM, but they were weaker than that of ITC at 0.1 μM (P < 0.01) and similar to that of ITC at 0.3 μM. Moreover, the CO displacement rates of SS750 at 0.1 and 0.3 μM for C. krusei cytochrome P450 were 52.4 and 22.2%, respectively. The binding affinity of SS750 was similar to that of FLC, weaker than that of ITC at 0.1 μM (P < 0.05), stronger than that of FLC (P < 0.01), and similar to that of ITC at 0.3 μM. In contrast, the CO displacement rates of SS750 at 30 and 300 μM for rat liver and human liver cytochrome P450s were 96.1 and 83.9% and 95.5 and 90.2%, respectively. The binding affinities of SS750 were similar to those of FLC and ITC and weaker than those of KTC at 30 μM (P < 0.05); they were also similar to those of FLC and weaker than those of KTC at 300 μM (P < 0.01) for rat and human liver cytochrome P450s.

FIG. 3.

Affinities of binding of SS750 (○), FLC (▴), ITC (□), and KTC (•) to the microsomal cytochrome P450 of C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. krusei ATCC 6258, rat liver, and human liver on the basis of the carbon monoxide displacement spectrum. ITC was not tested at a concentration of >100 μM because of its insolubility. The differences in absorbance between 448 nm (C. albicans and C. krusei) or 450 nm (rat liver and human liver) and 490 nm are shown as a percentage of that observed in controls. Results are the means ± standard errors of three experiments. Symbols: * and **, P < 0.05, and P < 0.01, respectively, versus the results for SS750, according to Tukey’s multiple comparison.

DISCUSSION

Numerous attempts have been made to develop novel antifungal agents because of the recent increases in the rates of fungal infections in immunocompromised hosts. However, only a few agents are clinically available, despite the increased need for drugs with more effective and safer profiles than those currently available. In the present study, SS750 was evaluated for its potential as an antifungal agent.

The in vitro antifungal activities of SS750 against the Candida species and C. neoformans strains tested were stronger than those of FLC. Although FLC-resistant C. albicans strains resistant on the basis of NCCLS breakpoints may show cross-resistance to SS750, the most important advantage of SS750 is its increased activity against strains that are intrinsically resistant to FLC, such as C. krusei and C. glabrata. Furthermore, in the survival study, oral SS750 proved to be the most effective drug treatment for systemic and pulmonary candidiasis caused by C. albicans in immunosuppressed mice. The pharmacokinetic study of SS750 was reported by Kogure et al. (T. Kogure, K. Yoshimura, R. Ikeda, I. Kawase, K. Kuramoto, H. Oka, and K. Tachibana, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1082, p. 198, 2000). Although SS750 is eliminated quickly (elimination half-life, 1.4 h) after administration of a single oral dose of SS750 (4 mg/kg of body weight) to male rats, it has a maximum concentration in serum of 1.89 μg/ml, and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve from time zero to infinity is 7.07 μg · h/ml. Moreover, SS750 is highly bioavailable (75.8%). Radiolabeled SS750 has been demonstrated to have a high absorption ratio (>93.7%), to be widely distributed throughout the body, and to have a relatively low plasma protein-binding rate (52.9 to 63.3%) in rats. The pharmacokinetic properties of SS750 participate in its high degree of efficacy in animal models; however, further examination will be necessary in order to interpret the in vivo results.

In order to elucidate the mechanism for the observed in vitro increase in the antifungal activity of SS750 against C. krusei, we focused on the inhibitory effects on cell-free ergosterol biosynthesis, as catalyzed by cytochrome P450 sterol 14α-demethylase (P45014dm), the target enzyme; we also observed the affinity of binding of SS750 to microsomal cytochrome P450 by CO-P450 complex formation in C. krusei. Moreover, as a safety profile, we compared the affinities of binding of SS750 to microsomal cytochrome P450 in mammalian livers.

C. krusei is inherently resistant to FLC. Orzco et al. (16) reported that this resistance is due to the decreased susceptibility of P45014dm to the inhibitory effect of FLC. The results of our studies with FLC and C. albicans and C. krusei resembled those reported by Orzco et al. (16), although the strains used in that study were different from those used in the present study. Briefly, the inhibitory effect of SS750 on P45014dm in the cell extract of C. krusei was greater than that of FLC (i.e., by 3.7 times), whereas SS750 inhibited the P45014dm of C. albicans a little more effectively than FLC did (i.e., by 1.5 times). Furthermore, it is well known that the intracellular accumulation of antifungal agents is important for their antifungal activities. Marichal et al. (11) reported that the low level of intracellular accumulation of FLC due to its highly hydrophilic property perhaps contributes much more to the primary resistance of C. krusei to FLC. From our results, ITC, the most hydrophobic triazole in the present study, showed the strongest antifungal activity among the triazole derivatives tested against C. krusei, whereas the inhibitory activity of P45014dm against C. krusei was identical to that of SS750. The Prolog P values, which estimate hydrophobic properties, were 1.114 for SS750, −0.016 for FLC, and 6.074 for ITC. SS750, which possesses the ethylsulfonyl gem-difluoromethylene moiety, is more hydrophobic than FLC, and it might accumulate in C. krusei and the other Candida species and C. neoformans strains tested to a greater extent than FLC did, resulting in the increased growth-inhibitory activity of SS750 (11). A comparative study of the intracellular accumulations of radiolabeled SS750 and the reference drugs will be necessary to elucidate further the mechanisms of the activity of SS750 against C. krusei.

SS750 and FLC showed similar strong binding affinities to microsomal cytochrome P450 in C. albicans. This result reflects the considerable differences in the inhibitory effects of P45014dm in the cell extract, as reported previously for FLC (23). Although SS750 showed a relatively strong affinity of binding to microsomal cytochrome P450 in C. krusei, FLC did not. These results appear to correlate with the inhibitory activities of SS750 and FLC for the C. albicans and C. krusei P45014dms. ITC showed a strong affinity of binding to microsomal cytochrome P450, suggesting that in C. albicans and C. krusei, ITC is a more potent inhibitor of CO-P450 complex formation than either SS750 or FLC.

Cytochrome P450s are a superfamily of heme-containing mixed-function oxygenases that are expressed in many mammalian tissues and that are found in the highest levels in liver tissue. Therefore, safe azole antifungal drugs must be highly selective for fungal cytochrome P450 as opposed to mammalian cytochrome P450. The binding affinity of SS750 for mammalian cytochrome P450 was weak even at a concentration of 300 μM, a finding similar to that observed in the case of FLC. In contrast, the affinity of binding of KTC to mammalian cytochrome P450, even at a concentration of 10 μM, was stronger than that of SS750. KTC is known to negatively affect steroid synthesis in adrenal and other tissues in humans by inhibiting human cytochrome P450 (4, 18). In contrast, FLC is a well-known antifungal agent with fewer adverse effects than those observed with KTC treatments. The affinity of binding of SS750 to mammalian cytochrome P450 was comparable to that of FLC. Accordingly, as for FLC treatment, treatment with SS750 is expected to result in adverse effects that are fewer in number and less severe than those produced by treatment with KTC. However, further evaluation of the effects of SS750 on cytochrome P450 in humans will be necessary to ensure the safety of treatment with this drug, i.e., with regard to its potential for drug-drug interactions and genetic polymorphisms.

In conclusion, the in vitro activity of SS750 against Candida species and C. neoformans is stronger than that of FLC. In particular, the most important advantage of SS750 is its increased activity against C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, and C. glabrata. Furthermore, SS750 shows a higher degree of efficacy against candidiasis caused by C. albicans in mice. SS750 strongly inhibits P45014dm and binds to the cytochrome P450 of C. krusei, indicating that SS750 acts by inhibiting fungal cell P45014dm. Moreover, SS750 appears to have less of an affinity to mammalian cytochrome P450. These data suggest that SS750 might have potential for clinical efficacy in the treatment of deep mycoses caused by Candida species and C. neoformans in immunocompromised humans from the viewpoint of its antifungal activity and safety.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toshimitsu Uchiyama, Department of Pharmacology, Toho University School of Medicine, for guidance during the study and reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barrett-Bee, K. J., A. C. Lane, and R. W. Turner. 1986. The mode of antifungal action of tolnaftate. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 24:155–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eto, H., Y. Kaneko, S. Takeda, M. Tokizawa, S. Sato, K. Yoshida, S. Namiki, M. Ogawa, K. Maebashi, K. Ishida, M. Matsumoto, and T. Asaoka. 2001. New antifungal 1,2,4-triazoles with difluoro (substituted sulfonyl) methyl moiety. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 49:173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fridkin, S. K., and W. R. Jarvis. 1996. Epidemiology of nosocomical fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fromtling, R. A. 1988. Overview of medically important antifungal azole derivatives. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1:187–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hitchcock, C. A., S. B. Brown, E. G. V. Evans, and D. J. Adams. 1989. Cytochrome P-450-dependent 14α-demethylation of lanosterol in Candida albicans. Biochem. J. 260:549–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Japanese Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 1987. Guidelines for animal experimentation. Japanese Association for Laboratory Animal Science, Tokyo, Japan.

- 7.Kauffman, C. A., and P. L. Carver. 1997. Antifungal agents in the 1990s. Drugs 53:539–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larocco, M. T., and S. J. Burgert. 1997. Infection in the bone marrow transplant recipient and role of the microbiology laboratory in clinical transplantation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:277–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lortholary, O., and B. Dupont. 1997. Antifungal prophylaxis during neutropenia and immunodeficiency. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:477–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marichal, P., J. Gorrens, M.-C. Coene, L. L. Jeune, and H. Vanden Bossche. 1995. Origin of differences in susceptibility of Candida krusei to azole antifungal agents. Mycoses 38:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariott, M. S. 1980. Inhibition of sterol biosynthesis in Candida albicans by imidazole-containing antifungals. J. Gen. Microbiol. 117:253–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikami, Y., T. Sakamoto, K. Yazawa, Y. Tanaka, and A. Matsumae. 1994. Effect of carrier solvents on the efficacy of oral itraconazole therapy in aspergillosis in mice. Jpn. J. Med. Mycol. 35:263–267. [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing for yeasts. Approval standard. Document M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 15.Omura, T., and R. Sato. 1964. The carbon monoxide-binding pigment of liver microsomes. J. Biol. Chem. 239:2370–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orzco, A. S., L. M. Higginbotham, C. A. Hitchcock, T. Parkinson, D. Falconer, A. S. Ibrahim, M. A. Ghannoum, and S. G. Filler. 1998. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida krusei. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2645–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patel, R., and C. V. Paya. 1997. Infections in solid-organ transplant recipients. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:86–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perfect, J. R., M. H. Lindsay, and R. H. Drew. 1992. Adverse drug reactions to systemic antifungals: prevention and management. Drug Safety 7:323–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poirier, J. M., F. Berlioz, F. Isnard, and G. Cheymol. 1996. Marked intra- and inter-patient variability of itraconazole steady state plasma concentrations. Therapie 51:163–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rex, J. H., M. G. Rinaldi, and M. A. Pfaller. 1995. Resistance of Candida species to fluconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabra, R., and R. A. Branch. 1990. Amphotericin B nephrotoxicity. Drug Safety 5:94–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanden Bossche, H., P. Marichal, J. Gorrens, D. Bellens, H. Verhoeven, M.-C. Coene, W. Lauwers, and P. A. J. Janssen. 1987. Interaction of azole derivatives with cytochrome P-450 isozymes in yeast, fungi, plants and mammalian cells. Pestic. Sci. 21:289–306. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venkateswarlu, K., D. W. Denning, N. J. Manning, and S. L. Kelly. 1996. Comparison of D0870, a new triazole antifungal agent, to fluconazole for inhibition of Candida albicans cytochrome P-450 by using in vitro assays. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1382–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh, T. J., C. Gonzalez, E. Roilides, B. U. Mueller, N. Ali, L. L. Lewis, T. O. Whitcomb, D. J. Marshall, and P. A. Pizzo. 1995. Fungemia in children infected with the human immunodeficiency virus: new epidemiologic patterns, emerging pathogens, and improved outcome with antifungal therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 20:900–906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]