Abstract

We compared the efficacy of ceftriaxone combined with gentamicin, both given once a day, with that of cloxacillin given every 4 h plus gentamicin given once a day or in three daily doses (t.i.d.) for the treatment of experimental methicillin-susceptible staphylococcal endocarditis. The antibiotics were administered by using human-like (H-L) pharmacokinetics that simulated the profiles of these drugs in human serum. Animals with catheter-induced endocarditis were infected intravenously with 105 CFU of Staphylococcus aureus S5 (MICs and minimal bactericidal concentrations of cloxacillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin, 0.5 and 2 μg/ml, 4 and 8 μg/ml, and 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, respectively). The animals were then treated for 24 h with cloxacillin at a dose of 2 g that simulated H-L pharmacokinetics (H-L 2 g) every 4 h alone or combined with gentamicin (administered at doses of H-L 1 mg/kg of body weight every 8 h or H-L 4.5 mg/kg every 24 h) or with ceftriaxone at H-L 2 g every 24 h alone or combined with gentamicin (administered at doses of H-L 1 mg/kg every 8 h or H-L 4.5 mg/kg every 24 h). The results of therapy for experimental endocarditis due to the S5 strain showed that (i) cloxacillin alone is more effective than ceftriaxone alone in reducing the bacterial load (P < 0.01), (ii) the combination of cloxacillin or ceftriaxone with gentamicin is more effective than each of these drugs alone (P < 0.01), and (iii) Ceftriaxone H-L plus gentamicin H-L 4.5 mg/kg, both administered every 24 h, showed efficacy similar to that of the “gold standard,” cloxacillin H-L plus gentamicin H-L 1 mg/kg t.i.d. (P > 0.05). An increase in the interval of administration of gentamicin to once daily resulted in a reduction in the numbers of bacteria in the vegetations equivalent to that achieved with the recommended regimen of cloxacillin plus gentamicin t.i.d. in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus. Ceftriaxone plus gentamicin, both administered once a day, may be useful for home-based therapy for selected cases of staphylococcal endocarditis.

In the preantibiotic era, endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus was almost universally fatal. Nowadays, even though antistaphylococcal antibiotics are available, endocarditis still carries a high rate of morbidity and mortality (6, 35). Antistaphylococcal penicillins such as oxacillin or methicillin are the antibiotics of choice for the treatment of infections due to methicillin-susceptible strains. The potential of narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, such as cefazolin and cephalothin, is evident from experimental studies, but few studies have investigated broad-spectrum cephalosporins in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) (21). The efficacies of β-lactams combined with aminoglycosides for the treatment of MSSA endocarditis have been demonstrated in experimental studies (29, 30), but use of the combination is not recommended in humans (38). It is accepted that aminoglycosides must be administered for a minimum of 15 days when treating staphylococcal prosthetic endocarditis (1). However, to avoid the potential toxic effects of prolonged aminoglycoside therapy, new treatment regimens, such as those that increase the aminoglycoside dosing interval, are being studied. Pharmacodynamic data obtained from animal models (17, 18, 37) have shown concentration-dependent killing by the aminoglycosides, which supports the idea that administration of these drugs once a day might be more effective. Along this line, gentamicin given once a day has been shown to be effective against experimental endocarditis due to viridans group streptococci (2, 11, 28) and experimental endocarditis due to Enterococcus faecalis (13, 20) and in in vitro simulations of enterococcal endocarditis (14, 32). To date, the efficacy of gentamicin administered once a day against MSSA has not been evaluated.

The recommended treatment for left native valve endocarditis due to MSSA is nafcillin or cloxacillin for 4 to 6 weeks (38). This regimen implies prolonged treatment in a hospital since administration on a home-therapy basis is complicated. It would be desirable to find alternatives that permit more convenient once-a-day administration for outpatient treatment. The prolonged half-life (t1/2) of ceftriaxone or teicoplanin allows once-a-day administration, and combinations of these drugs with aminoglycosides also administered once a day could be used as outpatient therapy for endocarditis. In experimental and clinical studies investigating treatments for streptococcal endocarditis, the efficacy of ceftriaxone plus aminoglycosides, both administered once a day, was similar to that of penicillin plus aminoglycosides 2, 8, 9; (H. F. Chambers, S. Kennedy, M. Fournier, M. S. Rouse, and W. R. Wilson, Program Abstr. 30th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 701, p. 203, 1990; C. W. Dorscher, B. M. Tallan, M. S. Rouse, J. M. Steckelberg, H. C. Chambers, and W. R. Wilson, Program Abstr. 30th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 700, p. 203, 1990). Additionally, the efficacy of teicoplanin plus gentamicin both administered once a day was similar to that of the standard therapy of ampicillin plus gentamicin in a rabbit model of enterococcal endocarditis (20).

In the case of staphylococcal endocarditis due to methicillin-sensitive strains, ceftriaxone plus gentamicin might be feasible as home-based therapy for selected patients with this condition. Once-a-day administration of this combination has not been studied in the treatment of MSSA experimental endocarditis. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of ceftriaxone plus gentamicin, both administered once a day, by using human-like (H-L) pharmacokinetics in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to MSSA in rabbits.

(This work was presented in part at the 35th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 17 to 20 September, 1995 [J. Gavalda, M. LaGuarda, J. A. Capdevila, L. Pou, E. Crespo, and A. Pahissa, Abstr. 35th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. B44, p. 33, 1995].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In vitro susceptibility studies.

We studied five methicillin-susceptible, non beta-lactamase-overproducing S. aureus strains isolated from patients with endocarditis. The in vivo studies were performed with the S5 strain. Working stock cultures were kept frozen at −70°C in double-strength skim milk medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Before each experiment, one aliquot was thawed and inoculated onto 5% sheep blood Columbia agar plates (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France). Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (CAMHB; bioMérieux) was used as the test medium. The following drugs were supplied by the indicated manufacturers: gentamicin, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.; cloxacillin, Antibioticos SA Madrid, Spain; and ceftriaxone, Roche SA, Madrid, Spain. Antibiotic solutions were prepared fresh on the day of use, following the recommendations of the manufacturers.

MICs were determined in duplicate by the microdilution method, in keeping with the procedures of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (24). Minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) were determined after 48 h of incubation of 0.025 ml each from the control well, from the first well with visible growth, and from all wells without visible growth plated onto 5% sheep blood Columbia agar plates for determination of the colony counts. S. aureus ATCC 29213 was used as the test control strain. The MBC was defined as the lowest concentration of antibiotic that killed at least 99.9% of the initial inoculum (16).

To perform the time-kill synergy studies, we followed the method described by Sahm and Torres (27). Prior to inoculation, each tube of fresh, prewarmed CAMHB was supplemented with gentamicin (final concentrations, 0.125, 0.5, and 1 μg/ml) either alone or in combination with cloxacillin (final concentrations, 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml) or ceftriaxone (final concentrations, 4 and 8 μg/ml). A positive-growth tube without antibiotics was used as a control. The test tubes were inoculated with 107 CFU of S. aureus in the logarithmic phase of growth per ml and incubated at 37°C in room air, and the log10 number of CFU per milliliter was determined after 0, 4, and 24 h of incubation. Synergy was defined as a ≥2 log10 decrease in the numbers of CFU/ml between the test tube with the combination and the test tube with the most active agent alone after 24 h, and the number of surviving organisms in the presence of the combination had to be ≥2 log10 CFU/ml below the starting inoculum. The combination was considered to have bactericidal activity when a ≥3 log10 reduction in colony counts was reached.

Animals.

New Zealand White rabbits (body weight, 2 kg) were obtained from BK Universal (Barcelona, Spain). The animals were housed in the animal facility of our hospital, which is equipped with automatic air exchange with a HEPA filter and a circadian light cycle. They were nourished with sterile water and food ad libitum.

Pharmacokinetic studies.

Cloxacillin, gentamicin, and ceftriaxone were administered by using a system that produces pharmacokinetics in rabbit serum that mimic the profile in human serum after an intravenous (i.v.) infusion of cloxacillin at 2 g every 4 h, ceftriaxone at 2 g every 24 h, gentamicin at 1 mg/kg of body weight every 8 h, or gentamicin at 4.5 mg/kg every 24 h. We used a computer-controlled infusion pump (Alice King) that delivered decreasing quantities of drug. The computer software was written by our group. With this program, the flow rate of the pump can be changed automatically and flow-rate sequences can be repeated as often as required. The approach involved three steps: (i) estimation of cloxacillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin pharmacokinetic parameters in the rabbit; (ii) application of a mathematical model to determine the infusion rate required to reproduce human pharmacokinetics in the animals; and (iii) in vivo experimental pharmacokinetic studies performed to simulate in rabbits the pharmacokinetic profiles of cloxacillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin in humans.

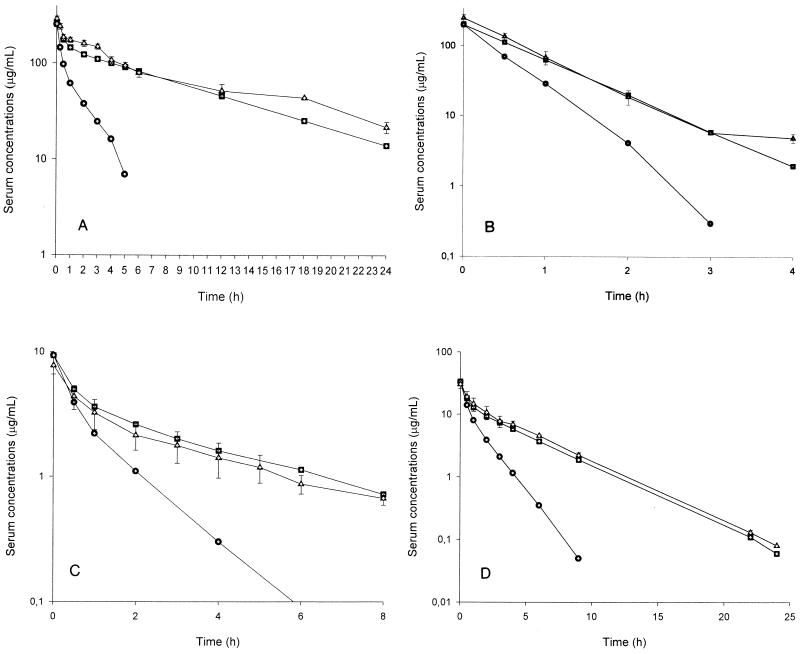

The pharmacokinetic studies which led to the H-L pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone and gentamicin in rabbits, including the explanation of the mathematical model used on the basis of an open two-compartment model, have been described previously (12, 20). The pharmacokinetic data from the human-adapted model of 2 g of ceftriaxone and gentamicin at 1 or 4.5 mg/kg given i.v. in rabbits are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1. The profile in serum and the pharmacokinetic parameters of ceftriaxone or gentamicin in rabbits administered by use of this model were similar to those of i.v. ceftriaxone or gentamicin in humans (12, 20).

TABLE 1.

Comparison of pharmacokinetic parameters of cloxacillin, gentamicin at two doses and ceftriaxone in in vivo studies

| Treatment and model | kel (h−1) | t1/2 (h) | AUC0-∞ (μg · h/ml) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceftriaxone at 2 g i.v.a | |||

| Rabbitb | 0.4 ± 0.04 | 1.66 ± 0.15 | 260.72 |

| Humanc | 0.1 | 6.92 | 1,506.3 |

| Rabbit, human-liked | 0.09 ± 0.002 | 7.21 ± 0.19 | 1,819 ± 82.72 |

| Cloxacillin at 2 g i.v. | |||

| Rabbit | 2.78 ± 0.5 | 0.25 ± 0.05 | 71.94 |

| Human | 1.155 | 0.6 | 173.16 |

| Rabbit, human-like | 1.05 ± 0.3 | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 191.52 ± 1.43 |

| Gentamicin at 1 mg/kg i.v. | |||

| Rabbit | 0.64 ± 0.22 | 1.09 ± 0.3 | 9.6 |

| Human | 0.27 | 2.54 | 18 |

| Rabbit, human-like | 0.27 ± 0.034 | 2.5 ± 0.37 | 15.80 ± 1.24 |

| Gentamicin at 4.5 mg/kg i.v. | |||

| Rabbit | 0.64 ± 0.22 | 1.09 ± 0.3 | 24.05 |

| Human | 0.25 | 2.8 | 66.2 |

| Rabbit human-like | 0.24 ± 0.014 | 2.0 ± 0.18 | 76.84 ± 17.7 |

The pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated on the basis of an open one-compartment model.

t1/2 and kel data are for healthy rabbits treated with 100 mg of cloxacillin per kg, 6 mg of gentamicin per kg, and 50 mg of ceftriaxone per kg i.v. The AUC0-∞ was calculated from the data for an ideal profile obtained with a C0 of 150 μg/ml for cloxacillin, a concentration at 0.5 h (C0.5) of 5 μg/ml for gentamicin at a dose of 1 mg/kg, a concentration at 0.5 h of 18 μg/ml for gentamicin at 4.5 mg/kg, and a C0 of 256.8 μg/ml for ceftriaxone and the kel of each drug in rabbits.

kel, t1/2, and AUC0-∞ were obtained from an ideal profile in human serum of 2 g of cloxacillin, 1 and 4.5 mg of gentamicin per kg, and 2 g of ceftriaxone (22, 25, 31).

Data are for H-L pharmacokinetics of 2 g of cloxacillin, 1 and 4.5 mg of gentamicin per kg, and 2 g of ceftriaxone.

FIG. 1.

Results of pharmacokinetic studies in rabbits with H-L pharmacokinetics of 2 g of ceftriaxone (A), 2 g of cloxacillin (B), gentamicin at 1 mg/kg (C), and gentamicin at 4.5 mg/kg (D). Circles, ideal pharmacokinetics in rabbits; squares, pharmacokinetics in humans; triangles, H-L pharmacokinetics in rabbits.

The first step needed to obtain H-L pharmacokinetics of cloxacillin involved the estimation of cloxacillin pharmacokinetic parameters in the rabbit. Blood was drawn from a carotid catheter at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min after administration of an i.v. dose of 100 mg of cloxacillin per kg to five healthy rabbits. The test tubes with the blood were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 min, and the serum was removed and stored at −70°C. All the serum samples were processed in the same assay. Cloxacillin concentrations were determined by the bioassay method with S. aureus ATCC 6538P as the test organism and antibiotic agar 5 as the assay medium. Standard curves were determined with cloxacillin solutions (10, 14, 18, 22, and 26 μg/ml) in pooled rabbit serum. The serum samples were also diluted in pooled rabbit serum so that their inhibition zone size diameters would be within the range of those for the standard curve. The concentrations in serum were extrapolated from the standard curve. The standard samples were studied in quintuplicate, and the serum samples were studied in triplicate. The results were expressed as micrograms per milliliter of blood. The linearity (r2) of the standard curve was 0.95. The sensitivity of the assay was 3.1 μg/ml of sample, and the between- and within-day coefficients of variation for replicates (n = 7) at 10 and 40 μg/ml were less than 5%. The serum elimination constant rate (kel) and the volume of distribution (V; in liters per kilogram) of cloxacillin in rabbit serum on the basis of an open one-compartment model were determined by using a nonlinear least-squares regression analysis of the concentration in serum-versus-time curve.

The second step was application of a mathematical model to determine the doses required to reproduce in rabbits the drug levels observed in humans after administration of 2 g of cloxacillin. The mathematical model for administration of drugs with H-L pharmacokinetics on the basis of an open one-compartment model has been published previously (11, 13). Finally, studies were done to simulate in healthy rabbits the pharmacokinetic profile of 2 g of cloxacillin given every 4 h in humans. Briefly, two polyethylene catheters (inner diameter, 0.81 mm; outer diameter, 1.27 mm; Portex SA, Hythe, England) were inserted, one into the carotid artery (sampling) and the other into the vena cava through the jugular vein (infusion). Both lines were tunneled subcutaneously and brought to the interscapular region. The external portion of the jugular catheter was connected to a flowthrough swivel and then to a computer-controlled infusion pump system, as previously described (12, 20). The pump system was set up to deliver an i.v. infusion at previously calculated flow rates to simulate the kinetics in humans of 2 g of cloxacillin given i.v. This study was done with five rabbits. To determine serum cloxacillin concentrations, 2 ml of blood was sampled through the carotid artery catheter at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h after the start of infusion. The concentrations in serum were then assayed by the microbiological bioassay described above. Several pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated on the basis of an open one-compartment model to compare the pharmacokinetics of cloxacillin in rabbits, in the human-adapted model, and in humans. The pharmacokinetic parameters of cloxacillin were calculated with a concentration at time zero (C0) of 150 μg/ml.

In vivo efficacy studies in the model of experimental endocarditis.

Experimental aortic valve infective endocarditis was induced in male New Zealand rabbits (weight, 2 to 2.3 kg) as described previously (10, 11). Briefly, a polyethylene catheter was inserted through the right carotid artery into the left ventricle and was kept in place during the experiment. On the same day, one or two catheters (inner diameter, 0.81 mm; outer diameter, 1.27 mm; Portex SA), depending on the treatment group, were inserted into the inferior venacava through the jugular vein by the same technique mentioned above (10, 11) to administer the different antimicrobials. The infusion pump delivered 2 ml of 0.9% saline/h to keep the catheters patent until the beginning of antimicrobial administration. Twenty-four hours after placement of the intracardiac catheter, the different groups of animals were infected via the marginal ear vein with 1 ml of a saline solution containing 105 CFU of S. aureus S5 in the stationary phase of growth. Blood (1 ml) was obtained 16 h after infection and just before the initiation of antimicrobial therapy to confirm the presence of endocarditis. The blood specimen was mixed with 20 ml of molten tryptic soy agar (Difco Laboratories). The agar plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C in room air, and the presence of staphylococci was interpreted as indicative of infective endocarditis.

Antimicrobial therapy was started 16 h after inoculation and was maintained for 24 h. Cloxacillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin were administered with the computer-controlled infusion pump system. The infected rabbits were randomized into the following treatment groups: control without treatment; ceftriaxone at a dose of 2 g that simulated H-L pharmacokinetics (H-L 2 g) every 24 h i.v., cloxacillin at H-L 2 g every 4 h i.v., cloxacillin at H-L 2 g every 4 h i.v. plus gentamicin at H-L 1 mg/kg every 8 h i.v., cloxacillin at H-L 2 g every 4 h i.v. plus gentamicin at H-L 4.5 mg/kg every 24 h i.v., and ceftriaxone at H-L 2 g every 24 h i.v. plus gentamicin at H-L 4.5 mg/kg every 24 h i.v. After 24 h of treatment and 6 h after the end of the antibiotic infusion, the rabbits were killed with a lethal i.v. injection of sodium pentothal. The chest was immediately opened, the heart was excised and opened, and the aortic valve vegetation was removed aseptically. The animals in the control group were killed 24 h after infection. Only those animals with proper placement of the catheter, macroscopic evidence of vegetations at the time of death, and S. aureus in cultures of blood obtained before the start of antimicrobial therapy were included in the study. The vegetations were rinsed with saline solution, weighed, and homogenized in 2 ml of tryptone soy broth (Difco Laboratories) in a tissue homogenizer (Stomacher 80). Homogenates were quantitatively cultured onto 5% sheep blood Columbia agar plates. In order to surmount the carryover effect, the vegetations of the animals treated with cloxacillin or ceftriaxone in combination with gentamicin were washed by centrifugation of the homogenate at 2,500 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and the bacterial pellet was resuspended in drug-free medium. We used two washings to ensure extensive drug removal. The homogenates of vegetations from animals treated with cloxacillin or ceftriaxone alone were not washed because we needed a 10−3 dilution to obtain a culture of organisms that could be counted. The plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C in room air. The results were expressed as the number of log10 CFU of S. aureus S5 per gram of vegetation. Bacterial densities in valvular vegetations calculated to be between 0 and 2 log10 CFU/g were reported as 2 log10 CFU/g rather than 0 log10 CFU/g because of the potential errors associated with the low weight of the valvular tissue. The results were expressed as the mean and the 95% confidence interval of the number of log10 CFU of S. aureus S5 per gram of vegetation. Differences in the number of log10 CFU of staphylococci per gram of vegetation were compared by one-way analysis of variance. When the F value was significant, the data for each treatment group were compared with those for the control group and each of the other treatment groups by Scheffe's test. P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

In vitro susceptibility studies.

The MICs and MBCs of cloxacillin, ceftriaxone, and gentamicin for the S. aureus S5 strain were 0.5 and 2 μg/ml, 4 and 8 μg/ml, and 0.5/1 μg/ml, respectively. The range of MICs of these antibiotics for the other four strains of S. aureus were 0.5 to 1 μg/ml for cloxacillin, 4 to 16 μg/ml for ceftriaxone, and 0.5 to 1 μg/ml for gentamicin.

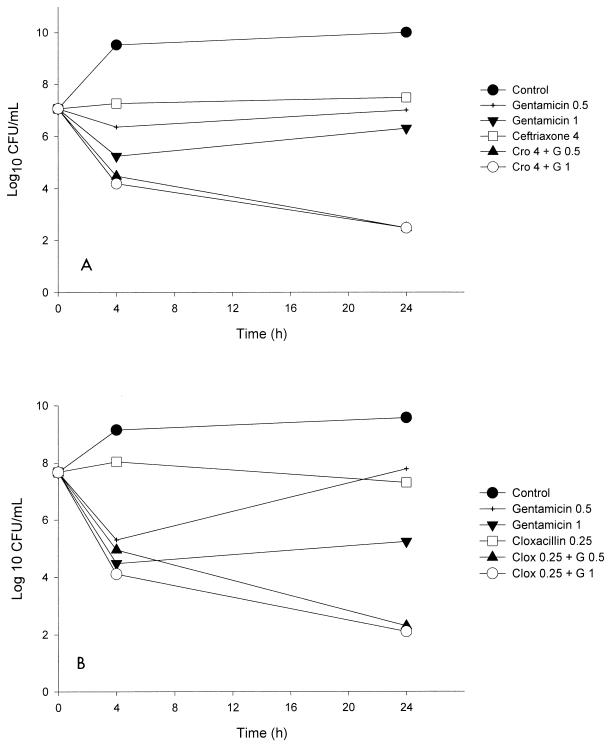

The results of the time-kill studies for the combination ceftriaxone plus gentamicin are shown in Table 2. The combination of 4 μg of ceftriaxone per ml plus 0.5 or 1 μg of gentamicin per ml resulted in synergistic activity against all five strains studied and was bactericidal for four of the strains, including strain S5. The graphic representation of the time-kill curve for strain S5 is shown in Fig. 2.

TABLE 2.

Results of time-kill curve studies for combinations of ceftriaxone and gentamicin against five strains of S. aureus

| Antimicrobial agent (dose [mg/kg]) | Change in log10 CFU/ml at the indicated times with respect to the initial inoculum

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S. aureus S5 (4/0.5)a

|

S. aureus M1.2 (16/0.5)

|

S. aureus D22-1 (4/0.5)

|

S. aureus A7-4 (4/1)

|

S. aureus O16-3 (4/0.5)

|

|||||||

| 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h | 4 h | 24 h | ||

| Growth control | +2.46 | +2.94 | +1.07 | +1.49 | +0.12 | +1.83 | +1.08 | +1.47 | +2.1 | +3.04 | |

| Ceftriaxone (4) | +0.20 | +0.42 | +0.62 | +1.02 | −1.38 | −2.15 | −2.13 | +0.04 | −0.49 | −1.31 | |

| Gentamicin (0.5) | −0.7 | −0.06 | +0.98 | +1.35 | −1.19 | −3.23 | −0.93 | +0.56 | −3.44 | +1.76 | |

| Gentamicin (1) | −1.82 | −0.76 | +0.86 | +1.09 | −1.51 | −3.25 | −4.73 | +0.1 | −2.31 | −1.38 | |

| Ceftriaxone (4) + gentamicin (0.5) | −2.58 | −4.59 | −0.06 | −2.51 | −1.32 | −5.44 | −3.47 | −4.09 | −2.03 | −5.17 | |

| Ceftriaxone (4) + gentamicin (1) | −2.87 | −3.82 | −0.03 | −2.21 | −1.51 | −5.84 | −4.18 | −5.23 | −3.45 | −5.49 | |

Values in parentheses are MIC of ceftriaxone/MIC of gentamicin, in micrograms per milliter.

FIG. 2.

(A) Time-kill curve for ceftriaxone (Cro) at 4 μg/ml and gentamicin (G) at 0.5 and 1 μg/ml for the treatment of endocarditis caused by S. aureus S5. (B) Time-kill curve for cloxacillin (Clox) at 0.25 μg/ml and gentamicin (G) at 0.5 and 1 μg/ml for the treatment of endocarditis caused by S. aureus S5.

Pharmacokinetic studies.

The rabbit pharmacokinetic data for ceftriaxone, determined with seven healthy rabbits that had received one i.v. bolus dose of 50 mg/kg, were as follows (values are means ± standard deviations [SDs]): distribution phase (α), 3.7 ± 0.41 h−1; elimination phase (β), 0.42± 0.07 h−1; k21 (rabbit elimination disposition rate constant at the distribution phase on the basis of an open two-compartment pharmacokinetic model), 1.53 ± 0.3 h−1; k13 (rabbit elimination constant from the central compartment, per hour), 1.07 ± 0.3 h−1; and V, 0.16 ± 0.01 liter/kg. The concentration profile in human serum produced by an i.v. injection of 2 g of ceftriaxone was successfully simulated in rabbits (Fig. 1A). The pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from the human-adapted model were similar to those for 2 g of ceftriaxone administered i.v. in humans (Table 1). This resulted in peak and trough ceftriaxone levels in rabbit serum (mean ± SD) of 242.7 ± 17.6 μg/ml at 15 min and 21.6 ± 2.9 μg/ml at 24 h, respectively.

The pharmacokinetic data for cloxacillin after an administration of an i.v. bolus of 100 mg/kg to five healthy rabbits were as follows: kel, 2.78 h−1; elimination t1/2 (t1/2β) 0.25 h; and the area under the concentration-time curve from time zero to infinity (AUC0-∞), 71.94 mg·h/ml. The pharmacokinetic profile in human serum after i.v. administration of 2 g of cloxacillin was also well reproduced in rabbits (Fig. 1B). Table 2 shows the pharmacokinetic data for the human-adapted model (kel, 1.05 ± 0.03 h−1, t1/2β, 0.66 ± 0.02 h; AUC0-∞ 191.52 ± 31.43 mg·h/ml), which were similar to those of 2 g of cloxacillin administered i.v. in humans.

The pharmacokinetic data for 6 mg of gentamicin per kg given i.v. to nine healthy rabbits were as follows: α, 2.96± 0.86 h−1; β, 0.6 ± 0.13 h−1; k21, 1.49 ± 0.23 h−1; k13, 1.14 ± 0.12 h−1; and V, 0.2 ± 0.05 liter/kg. The results for the human-adapted model in rabbits, which reproduce the pharmacokinetic parameters of i.v. administration of 1 and 4.5 mg of gentamicin per kg in humans, are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 1C and D.

In vivo efficacy studies in model of experimental endocarditis.

The results of the different therapeutic regimens for experimental endocarditis caused by S. aureus S5 are shown in Table 3. After 24 h of treatment, bacterial counts were reduced in the vegetations of the animals treated with all the drug regimens compared to those in the control group (P < 0.001). Comparisons between the treated groups revealed that ceftriaxone administered alone was less effective than cloxacillin administered alone (P < 0.01). The combinations of gentamicin plus cloxacillin or ceftriaxone were significantly more effective than cloxacillin or ceftriaxone administered as single therapy (P < 0.01). Ceftriaxone at a dose that simulated H-L pharmacokinetics (ceftriaxone H-L) plus gentamicin at H-L 4.5 mg/kg, both administered once a day, was effective and displayed activity similar to that of the “gold standard,” cloxacillin H-L plus gentamicin H-L 1 mg/kg three times a day (P > 0.05), and was more effective than cloxacillin or ceftriaxone alone (P < 0.01).

TABLE 3.

Treatment of experimental endocarditis caused by S. aureus S5 with a H-L pharmacokinetic profiles of cloxacillin alone or in combination with gentamicin and H-L profiles of ceftriaxone alone or with gentamicin

| Treatment groupa | No. of rabbits that survived/total no. tested | Log10 CFU/g of vegetationb |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 13/16 | 11.44 (11.09-11.78) |

| Cloxacillin | 16/20 | 5.59 (4.93-6.25)c,d |

| Cloxacillin + gentamicin three times a day | 15/18 | 3.27 (2.57-3.97)c,e |

| Cloxacillin + gentamicin once a day | 12/14 | 2.61 (2.25-2.97)c,e |

| Ceftriaxone | 14/17 | 7.01 (6.23-7.79)c |

| Ceftriaxone + gentamicin once a day | 12/16 | 3.74 (2.88-4.61)c,e |

The treatments consisted of cloxacillin at H-L 2 g every 4 h i.v., ceftriaxone at H-L 2 g every 24 i.v., gentamicin at H-L 1 mg/kg every 8 h, at and gentamicin at 4.5 mg/kg every 24.

Results are means (95% confidence intervals).

P < 0.001 versus control.

P < 0.01 versus ceftriaxone.

P < 0.01 versus cloxacillin and ceftriaxone.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to determine the efficacy of ceftriaxone plus gentamicin, both administered once a day as at doses that simulate H-L pharmacokinetics, compared to that of the standard treatment of cloxacillin plus gentamicin for the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to MSSA. Our results showed that the two combinations were equally effective and that the combinations were superior to treatment with cloxacillin or ceftriaxone alone. Cloxacillin was somewhat more effective than cephalosporin as single-drug therapy.

Narrow-spectrum cephalosporins are mainly active against gram-positive organisms and are equivalent to antistaphylococcal penicillins against MSSA in vitro (19). They have also been shown to have efficacy in the treatment of experimental MSSA endocarditis. The activities of cephalothin and cefazolin were similar to that of methicillin for the treatment of experimental staphylococcal endocarditis, despite the in vitro inactivation of cefazolin by staphylococcal beta-lactamase (4, 26). In contrast, the broad-spectrum cephalosporins are, in general, less active in vitro than nafcillin and cefazolin against MSSA (15). In the study of Dhawan et al. (5), who compared the activities of cefmenoxime, cefotaxime, latamoxef, and nafcillin in the treatment of experimental MSSA endocarditis, nafcillin showed an efficacy similar to that of latamoxef and better than those of cefmenoxime and cefotaxime. Steckelberg et al. (34) compared the efficacies of cefpirome, cefazolin, cefuroxime, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftizoxime, cefoperazone, ceftazidime, and nafcillin in the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to MSSA. In vivo, nafcillin was the most active agent and was significantly more effective than ceftizoxime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, cefuroxime, or cefazolin. Our results concur with those reported before. The outcome for the group treated with ceftriaxone was poorer than that for the group treated with cloxacillin alone. Ceftriaxone alone was less effective than cloxacillin for the treatment of experimental MSSA endocarditis.

Penicillin or an antistaphylococcal penicillin combined with an aminoglycoside has been shown to be effective in vitro and in animal models of MSSA endocarditis (3, 29, 30). There are few experimental data on the efficacy of ceftriaxone combined with an aminoglycoside for the treatment of staphylococcal endocarditis. Tallan et al. reported that ceftriaxone at doses of 7.5 mg/kg given intramuscularly (i.m.) combined with gentamicin at 1.5 mg/kg given i.m., both administered twice daily, was more active than 50 mg of cefazolin per kg administered i.m. alone thrice daily and was as active as cefazolin plus gentamicin at 1 mg/kg given i.m. in three separate doses (B. M. Tallan, M. S. Rouse, N. K. Henry, J. M. Steckelberg, and W. R. Wilson, Program Abstr. 31st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 364, p. 159, 1991). The results from our experiments are in concordance with those in previous reports; the efficacy of combination therapy was clearly superior to the efficacy of beta-lactams administered alone. The aminoglycoside dosing interval is still under discussion. A meta-analysis conducted by Munckhof et al. (23) evaluated all the randomized clinical studies dealing with once-a-day administration of aminoglycosides. They reported that aminoglycosides can be given once daily rather than in divided doses for the treatment of human infections other than endocarditis without a loss of efficacy or increased toxicity, offering greater simplicity and potentially improved cost-effectiveness. Recently, the efficacy of gentamicin administered once a day instead of in three divided doses has been evaluated for the treatment of nonstaphylococcal experimental endocarditis (2, 8, 11, 13, 14, 20, 28, 32). To date, the efficacy of gentamicin administered once a day against experimental MSSA endocarditis has not been evaluated. Our results confirm the fact that the efficacy of gentamicin given once daily in combination with either cloxacillin or ceftriaxone was similar to that of the combination of cloxacillin with the gentamicin given in three divided doses.

Ceftriaxone and teicoplanin have long t1/2s (6 to 9 h), making once-daily administration practicable. The evaluation of their efficacies when they are combined with aminoglycosides in a single dose for the treatment of experimental endocarditis due to different microorganisms could lead to a therapeutic strategy that allows treatment of this infection on an outpatient basis. Although it is possible that oxacillin may be administered via a programmable infusion pump for home-based therapy, this approach is not always available, and the therapeutic regimens that may be administered once a day merit further examination. Our group demonstrated that the efficacy of teicoplanin combined with gentamicin, both given once a day, was as effective as the gold standard treatment for experimental enterococcal endocarditis, which uses ampicillin plus gentamicin in three divided doses (20). The results from a recent clinical study by Venditti et al. (36) provide further evidence that a single daily dose of teicoplanin plus gentamicin could be a good option for the home-based treatment of selected cases of enterococcal endocarditis. Six patients with enterococcal endocarditis were cured when they were treated with teicoplanin in combination with gentamicin or netilmicin once a day. In addition, the efficacy of once-daily administration of aminoglycosides associated with ceftriaxone has been documented for the treatment of viridans group streptococcal endocarditis in humans (9, 33). Two clinical studies demonstrated that a 2-week regimen of ceftriaxone plus gentamicin once daily or 4 weeks of treatment with ceftriaxone is efficacious and safe for the treatment of penicillin-susceptible streptococcal endocarditis and may allow partial or complete outpatient management for selected patients. No experimental studies have evaluated this issue with an animal model of staphylococcal endocarditis. Our studies showed that ceftriaxone at H-L 2 g plus gentamicin at H-L 4.5 mg/kg, both administered once a day, was effective and displayed activity similar to that of the gold standard, cloxacillin H-L plus gentamicin at H-L 1 mg/kg three times a day, and was more effective than treatment with cloxacillin or ceftriaxone alone. There are few data on the efficacy of this combination in humans with staphylococcal endocarditis. Francioli (7) reported that a once-daily injection of ceftriaxone and gentamicin administered for 15 days was used successfully in Cameroon to treat 14 patients with endocarditis due to S. aureus.

Thus, the results obtained in our experiments suggest that the combination of ceftriaxone with gentamicin, both administered in a single daily dose, could be considered an alternative to the elective treatment and, in selected patients, after stabilization, as an outpatient therapeutic regimen in the treatment of MSSA endocarditis. However, further studies with animal models and humans are needed to confirm these data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bisno, A. L., W. E. Dismukes, D. T. Durack, E. L. Kaplan, A. W. Karchmer, D. Kaye, S. H. Rahimtoola, M. A. Sande, J. P. Sandford, C. Watanakunakorn, and W. R. Wilson. 1989. Antimicrobial treatment of infective endocarditis due to viridans streptococci, enterococci and staphylococci. JAMA 261:1471-1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blatter M., U. Flukiger, J. Entenza, M. P. Glauser, and P. Francioli. 1993. Simulated human serum profiles of one daily dose of ceftriaxone in the treatment of experimental streptococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1971-1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos, M. E., S. Rabinovich, and I. M. Smith. 1974. Therapy of experimental staphylococcal infection with antibiotic combinations. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 83:241-248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrizosa, J., J. Santoro, and D. Kaye. 1978. Treatment of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis: comparison of cephalothin, cefazolin, and methicillin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 13:74-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dhawan, V. K., H. Thadepalli, M. K. Maier, M. Nayyar, M. B. Bansal, and S. K. Chuah. 1984. Newer beta-lactam antibiotics in the treatment of experimental Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 14:165-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espersen, F., and N. Frimodt-Moller. 1986. Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. A review of 119 cases. Arch. Intern. Med. 146:1118-1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Francioli, P. B. 1993. Ceftriaxone and outpatient treatment of infective endocarditis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 7:97-115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francioli, P. B., and M. P. Glauser. 1993. Synergistic activity of ceftriaxone combined with netilmicin administered once daily for treatment of experimental streptococcal endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:207-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francioli, P. B., W. Ruch, D. Stamboulian, and the International Infective Endocarditis Study Group. 1995. Treatment of streptococcal endocarditis with a single daily dose of ceftriaxone and netilmicin for 14 days: a prospective multicenter study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 21:1406-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garrison, P. K., and L. R. Freedman. 1970. Experimental endocarditis. I. Staphylococcal endocarditis in rabbits resulting from placement of a polyethylene catheter in right side of the heart. Yale J. Biol. Med. 42:394-410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gavaldà, J., A. Pahissa, B. Almirante, M. Laguarda, E. Crespo, L. Pou, and F. Fernández. 1995. Effect of gentamicin dosing interval on therapy of viridans streptococcal experimental endocarditis with penicillin plus gentamicin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2098-2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gavaldà, J., C. Torres, C. Tenorio, P. Lopez, M. Zaragoza, J. A. Capdevila, B. Almirante, F. Ruiz, N. Borrell, C. Pigrau, F. Baquero, and A. Pahissa. 1999. Efficacy of ampicillin plus ceftriaxone in treatment of experimental endocarditis due to Enterococcus faecalis strains highly resistant to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:639-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gavaldà, J., P. J. Cardona, B. Almirante, J. A. Capdevila, M. Laguarda, L. Pou, E. Crespo, C. Pigrau, and A. Pahissa. 1996. Treatment of experimental endocarditis due to Enterococcus faecalis using once-daily dosing regimen of gentamicin plus simulated profiles of ampicillin in human serum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:173-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Houlihan, H. H., D. P. Stokes, and M. J. Rybak. 2000. Pharmacodynamics of vancomycin and ampicillin alone and in combination with gentamicin once daily or thrice daily against Enterococcus faecalis in an in vitro infection model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:79-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karchmer, A. W. 1995. Cephalosporins, p. 247-264. In G. L. Mandell, J. E. Bennett, and R. Dolin (ed.), Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's principles and practice of infectious diseases, 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 16.Knapp, C., and J. A. Moody. 1992. Tests to assess bactericidal activity. In H. D. Isenberg (ed.), Clinical microbiology procedures handbook. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 17.Leggett, J. E., B. Fantin, S. Ebert, K. Totsuka, W. Calame, H. Mattie, and W. A. Craig. 1989. Comparative antibiotic dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals in murine pneumonitis and thigh-infection models. J. Infect. Dis. 159:281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leggett, J. E., S. Ebert, B. Fantin, and W. A. Craig. 1991. Comparative dose-effect relations at several dosing intervals or beta-lactam, aminoglycoside and quinolone antibiotics against gram-negative bacilli in murine thigh-infection and pneumonitis models. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 74(Suppl.):179-184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livermore, D. M., and J. D. Williams. 1996. β-Lactams: mode of action and mechanisms of bacterial resistance, p. 502-578. In V. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 4th ed. The Williams & Wilkins Co., Baltimore, Md.

- 20.López, P., J. Gavaldà, M. T. Martin, B. Almirante, X. Gomis, C. Azuaje, N. Borrell, L. Pou, V. Falcó, C. Pigrau, and A. Pahissa. 2001. Efficacy of teicoplanin-gentamicin given once a day on the basis of pharmacokinetics in humans for treatment of enterococcal experimental endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1387-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McColm, A. A., D. M. Ryan, and P. Acred. 1984. Comparison of ceftazidime, cefuroxime and methicillin in the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis in rabbits. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 14:373-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mensa, J., J. M. Gatell, M. T. Jiménez de Anta, G. Prats, and A. Dominguez-Gil. 1994. Antimicrobianos, p. 2-138. In J. Mensa, J. M. Gatell, M. T. Jiménez de Anta, G. Prats, and A. Dominguez-Gil (ed.), Gu&ıacute;a terapéutica antimicrobiana, 4th ed. Masson, Barcelona, Spain.

- 23.Munckhof, W. J., M. L. Grayson, and J. D. Turnidge. 1996. A meta-analysis of studies on the safety and efficacy of aminoglycosides given either once daily or as divided doses. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 37:645-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests on bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 25.Patel, I. H., S. Chen, M. Parsonnet, M. R. Hackman, M. A. Brooks, J. Konikoff, and S. A. Kaplan. 1981. Pharmacokinetics of ceftriaxone in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 20:634-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouse, M. S., B. M. Tallan, N. K. Henry, J. M. Steckelberg, and W. R. Wilson. 1992. Animal models as predictors of outcome of therapy with broad spectrum cephalosporins. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29(Suppl. A):39-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sahm, D. F., and C. Torres. 1988. Effects of medium and inoculum variations on screening for high-level aminoglycoside resistance in Enterococcus faecalis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:250-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleh-Mghir, A., A. C. Crémieux, J. M. Vallois, M. Muffat-Jolly, C. Devine, and C. Carbon. 1992. Optimal aminoglycoside dosing regimen for penicillin-tobramycin synergism in experimental Streptococcus adjacens endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:2403-2407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sande, M. A., and K. B. Courtney. 1976. Nafcillin-gentamicin synergism in experimental staphylococcal endocarditis. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 88:118-124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sande, M. A., and M. L. Johnson. 1975. Antimicrobial therapy of experimental endocarditis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 131:367-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schentag, J. J., W. J. Jusko, J. W. Vance, T. J. Cumbo, E. Abrutyn, M. DeLattre, and L. M. Gerbracht. 1977. Gentamicin disposition and tissue accumulation on multiple dosing. J. Pharmacokinet. Biopharm. 5:559-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwank, S., and J. Blaser. 1996. Once versus thrice-daily netilmicin combined with amoxicillin, penicillin, or vancomycin against Enterococcus faecalis in a pharmacodynamic in vitro model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2258-2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sexton, D. J., M. J. Tenenbaum, W. R. Wilson, J. M. Steckelberg, A. D. Tice, D. Gilbert, W. Dismukes, R. H. Drew, D. T. Durack, and the Endocarditis Treatment Consortium Group. 1998. Ceftriaxone once daily for four weeks compared with ceftriaxone plus gentamicin once daily for two weeks for treatment of endocarditis due to penicillin-susceptible streptococci. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:1470-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steckelberg, J. M., M. S. Rouse, B. M. Tallan, D. R. Osmon, N. K. Henry, and W. R. Wilson. 1993. Relative efficacies of broad-spectrum cephalosporins for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus experimental infective endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:554-558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tornos, P., B. Almirante, S. Mirabet, G. Permanyer, A. Pahissa, and J. Soler Soler. 1999. Infective endocarditis due to Staphylococcus aureus: deleterious effect of anticoagulant therapy. Arch. Intern. Med. 159:473-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venditti, M., A. Tarasi, A. Capone, M. Galie, F. Menichetti, P. Martino, and P. Serra. 1997. Teicoplanin in the treatment of enterococcal endocarditis: clinical and microbiological study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40:449-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogelman, B., S. Gudmundsson, J. Leggett, J. Turnidge, S. Ebert, and W. A. Craig. 1988. Correlation of antimicrobial pharmacokinetic parameters with therapeutic efficacy in an animal model. J. Infect. Dis. 158:831-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson, W. R., A. W. Karchmer, A. S. Dajani, K. A. Taubert, A. Bayer, D. Kaye, A. L. Bisno, P. Ferrieri, S. T. Shulman, and D. T. Durack. 1995. Antibiotic treatment of adults with infective endocarditis due to streptococci, enterococci, staphylococci and HACEK microorganisms. JAMA 274:1706-1713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]