Abstract

A mixed culture of an hypermutable hexA Streptococcus pneumoniae mutant strain and its hexA+ isogenic ancestor was challenged with low cefotaxime concentrations. Despite identical original cefotaxime MICs, the hexA mutant population was significantly selected at very low concentrations, and all of the tested selected variants harbored the Thr550→Ala mutation in pbp2x. Since cefotaxime selects hypermutators, the risk of secondary acquisition of antibiotic resistance is increased; as expected, the cefotaxime-resistant mutants had a mutation frequency 10 times higher in response to to ciprofloxacin. The present study presents a model (not necessarily reflecting the clinical setting) illustrating the risk of selection of mutators in the evolution of multiple resistance.

During the last several years, a number of studies and reviews have addressed the relationship between antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae (4). The salient message of these various studies is that antibiotics exert a selective force on preexisting S. pneumoniae-resistant clones, most frequently belonging to particular serogroups and, not surprisingly, those in which the maximal density of cells are reached in human hosts and community. On the contrary, the possibility that antibiotics may influence the evolvability (14) of S. pneumoniae populations to develop antibiotic resistance has not been frequently considered. We model here the enrichment of hypermutable S. pneumoniae populations by hitchhiking with antibiotic resistance. This enrichment increases the adaptive possibilities of the entire S. pneumoniae population. This concept may have important implications for the understanding of the effects of antibiotics in the emergence (and not only in the selection) of multiple antibiotic resistance in S. pneumoniae.

Genetic variability in bacterial organisms is essentially the result of the interplay of processes of recombination and mutation. The role of recombination in the acquisition of penicillin resistance in S. pneumoniae is a well-recognized phenomenon by which a number of bacterial clones have acquired segments of penicillin-resistant penicillin-binding proteins from other types of streptococci, giving rise to hybrid genes presenting a high degree of mosaicism (3, 8). Mutational events as a primary source of antibiotic resistance in S. pneumoniae may occur in cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, and macrolides (6, 9, 16). Genes involved in methyl mismatch repair (MMR) play a central role in the avoidance of the emergence of mutations occurring during the replication process. In S. pneumoniae the hexA-hexB MMR genes are equivalent to the mutS-mutL genes in Escherichia coli. In organisms with a defective hexA function, the mutation frequency increases by about 10 fold (7, 13). In other organisms, bacterial populations with defective MMR systems significantly increase the rate of mutational antibiotic resistance (12). A competition model-system was established here to test whether subinhibitory cefotaxime concentrations were able to select a hypervariable hexA mutant S. pneumoniae population over its isogenic hexA+ ancestor and also to determine the reasons and possible consequences of this selective event. The competition was established between the isogenic strains S. pneumoniae R800 (R6 derivative, ami+, aliA+, aliB+, hexA+ strains) and S. pneumoniae R310 (R800 hexA::synspc derivative) (1). The respective mutation frequencies in Columbia blood agar (CBA) plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) containing rifampin (2 μg/ml) were 2.6 × 10−8 ± 0.07 × 10−8 for R800 and 1.06 × 10−7 ± 0.04 × 10−7 for R310 (mean of five separate experiments). Both strains had identical susceptibility to cefotaxime (0.008 μg/ml) and ciprofloxacin (0.5μg/ml) in repeated testing experiments with the conventional microdilution NCCLS method (10). A mixture of identical 1:1 volumes (mixture culture A) of S. pneumoniae R800 and R310 strains was prepared from separate 4-h cultures in Columbia broth lysed blood (CBLB). Then, 100 μl of mixture A was diluted in 5 ml of new prewarmed CBLB (mixture B), and a sample was immediately seeded into CBA. After overnight incubation, 100 colonies were restreaked on CBA plates containing or not containing spectinomycin (50 μg/ml). Initial inocula of both S. pneumoniae R800 and R310 in the seeding mixture B proved to be identical: 2.2 × 107 CFU/ml. The mixture was centrifuged and immediately frozen with glycerol (to prevent spontaneous lysis). Before this, an aliquot was incubated at 37°C for 4 h and, after this period, counts for both strains were determined as described above, and the results were quite similar: ca 8.5 × 108 CFU/ml. The next day, mixture B was thawed, and 100 μl was resuspended in 5 ml of fresh prewarmed CBLB medium (mixture C) and incubated for 4 h. A sample of the mixture was seeded in CBA and, after overnight incubation, 100 colonies were again restreaked on CBA plates with or without spectinomycin (50 μg/ml) for differential R800 (hexA+)-R310 (hexA mutant) counting. To assure the neutrality of the spectinomycin marker and of the hexA mutation in the absence of antibiotic, this procedure was followed repeatedly until 48 h. The proportion of the R310 strain in the total culture was essentially identical at 0 h (51%), 4 h (53%), 24 h (54%), and 48 h (49%), thus establishing the desired neutrality.

A procedure identical to that described above was performed in the presence of cefotaxime (Aventis Pharma, Romainville, France) concentrations ranging from 0.002 to 0.06 μg/ml. The fresh CBLB used for resuspension of cells grown during the previous 4-h period had the same cefotaxime concentrations. After 4 and 8 h of contact with cefotaxime, cells were centrifuged and then resuspended in antibiotic-free CBLB containing 100 U of P99 beta-lactamase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml to allow the enrichment of the residual population that may have survived the action of the antibiotic, as previously described (11). This procedure mimics the recolonization process after antibiotic use on patients. After an 18-h incubation, identical sample volumes from each cefotaxime concentration were seeded into CBA and, the next day, 100 individual colonies from each sample (and controls) were spotted onto CBA with or without spectinomycin for differential R800 (hexA+)-R310 (hexA mutant) counting. In all tests, three replicate experiments were run in parallel.

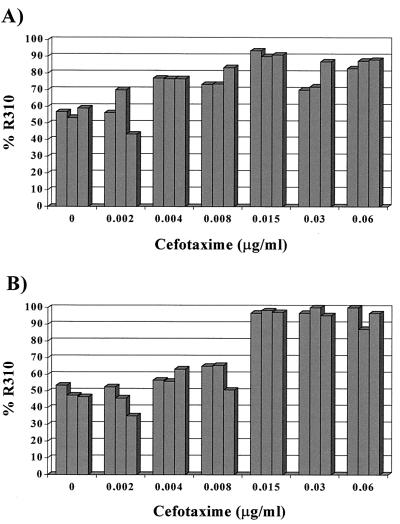

The results obtained in the experiments are presented in Fig. 1. After 4 h of challenge with a cefotaxime concentration of 0.002 μg/ml and subsequent enrichment of residual populations, the relative proportion of R310 (hexA mutant) and R800 (hexA+) remained essentially constant in relation to the controls without antibiotic (mean 0.71% decrease in the R310 proportion). After challenge with 0.004 and 0.008 μg/ml, the R310 (hexA mutant) population started to predominate in the enrichment cultures, with mean increases of 14.4 and 16.2% over the original proportion. After exposure to 0.015 μg/ml, the dominance of the R310 (hexA mutant) population was maximal (32.2% increase) and was maintained, at a lower rate, after challenge with 0.03 or 0.06 μg/ml (18.3 and 26% increases). After 8 h of exposure of the R310-R800 mixture, no R310 selection was detectable with 0.002 μg/ml (4.7% increase), but it started after challenge with 0.004 and 0.008 μg/ml (9.4 and 11.2% increases) and again increased to a maximum value of 0.015 μg/ml (48.2%). Selection was maintained at high levels after challenge with 0.03 or 0.06 μg/ml for 8 h. At this stage, >95% of the population is made up of the R310 (hexA mutant) hypermutable variant.

FIG. 1.

Changes in the frequency of S. pneumoniae R310 (hexA mutant) in mixed culture with the isogenic R800 (hexA+) strain after a 4-h (A) or an 8-h (B) challenge with increasing cefotaxime concentrations. The proportions were obtained from survivor cells after overnight culture in drug-free broth. The hypermutable R310 variant is selected at higher concentrations. Bars represent the results obtained from three replicate experiments.

These results indicate that in the hypermutable R310 S. pneumoniae variant population there was a higher number of survivors than among the wild-type ancestor population after a 4- or 8-h exposure to very low cefotaxime concentrations. This difference is reflected in the higher proportion of hexA mutant cells in the enrichment cultures. The selection of hypermutator variant cells could be explained as a hitchhiking phenomenon: the hexA mutant strain is more likely to develop advantageous mutations, in this case cefotaxime resistance, and thus the cefotaxime-resistant variants should be most frequently hypermutators. This possibility was fully confirmed in our experiments. First, a 10- 50-fold greater mutation frequency in response to cefotaxime (0.03 μg/ml) was consistently documented in the R310 variant compared to the R800 wild-type strain in five independent experiments (means of 3.7 × 10−7 and 1.13 × 10−8, respectively). Second, the pbp2x gene of five strains obtained after different challenge experiments (one with 0.03 μg/ml during 4 h and four with 0.008, 0.015, 0.03, and 0.06 μg/ml during 8 h) and of the two original strains R800 and R310, which had not been subjected to any antibiotic exposure, was PCR amplified (primers PBP2x-1 [5′-GGAATTCACACGATTTGCAATTAAAC-3′] and PBP2x-2 [5′-CCGGAATTCAGTAAAAATGTCACAATTCCA-3′]) and fully sequenced. The sequence of nonexposed R800 and R310 was fully conserved, but all five cefotaxime surviving strains showed the same Thr550→Ala change, which is known to produce cefotaxime resistance in S. pneumoniae (2, 5). The same mutation was detected in the original R310 strain after plating on plates containing 0.03 μg of cefotaxime/ml. In all strains having undergone such a change, the cefotaxime MIC rose to 0.12 μg/ml. In summary, the Thr550→Ala mutation was selected by cefotaxime, which resulted in an increase in the proportion of hypermutable hexA mutant variant.

It is difficult to ascertain whether the selected mutation was previously present in few individuals in the inoculum of the hypermutable strain or whether it emerged during the antibiotic challenge. At very low cefotaxime concentrations (0.002 μg/ml), the population density of both R800 and R310 after incubation is obviously higher than at higher concentrations, and thus the expected emergence of a mutation should be also higher, particularly for R310. Nevertheless, since this concentration is too low to kill the susceptible cells, selection does not take place. At immediately higher concentrations, the bacterial population density still increases, but a certain selection is simultaneously exerted for resistant variants, most probably arising from the hexA mutant strain. At higher concentrations, the cefotaxime-susceptible R800 and R310 populations decrease significantly in cell density, and the selection of cefotaxime-resistant R310 variants takes place. At even higher concentrations, cefotaxime-resistant mutants probably start to die, and the selection begins to be less efficient. Our results suggest that, particularly after a 4-h challenge, there is a peak of selection at intermediate concentrations (0.015 μg/ml), probably reflecting the compromise between the availability of mutants (proportional to the population size) and the antibiotic selective power. The existence of a selection window for resistant S. pneumoniae variants at particular antibiotic concentrations has been previously described by our group (11). We cannot discard the possibility of induced mutational events during antibiotic-promoted bacterial stress, since we have shown that ceftazidime is able to increase mutation frequency in E. coli (J. Blázquez, M.-R. Baquero, J. M. Gómez-Gómez, T. Coque, M. Lobo, and F. Baquero, Abstr. 39th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 33, 1999).

Finally, we should consider our results, which are based on the selection of hexA mutant hypermutators, to be only a model experiment to illustrate the evolutionary advantages of hypermutable phenotype in S. pneumoniae. First, the proportion of the mutator strain in the experiment was very high. This may occur in vivo by successful invasion of hypermutable strain, but if the mutant is expected to arise in the original population, the frequency should be much lower. If the hypermutable strain does not reach a sufficient number of cells, the possibility of getting an advantageous adaptive mutation (such as Thr550) should be very low. Second, we are not proposing here that hexA mutant hypermutators are the basic mechanism for mutational resistance in this species. Indeed, we failed to detect a significantly higher frequency of hexA or hexB mutants among a limited number of antibiotic-resistant strains (data not shown). An increase in recombinational events may explain this result (see below). Eventually, disruptions in Hex-independent systems of repair may be more effective in promoting resistance in the real world. A homologue of mutY in E. coli, specifically repairing A/G mismatches, has been recently found in S. pneumoniae (15). Note that the Thr550→Ala mutation in pbp2x leading to cefotaxime resistance is based on a ACG→GCG change.

The potential consequences of the selection of hypermutators during antibiotic therapy are of obvious clinical and epidemiological interest. In fact, four hexA mutant clones harboring the Thr550→Ala mutation selected by cefotaxime challenge had a consistently higher rate of mutation in response to ciprofloxacin (mean, 1.8 × 10−7) than the hexA+ original R800 strain (1.5 × 10−8). These mutants are now resistant to both cefotaxime and ciprofloxacin. Thus, the whole process of hypermutators selection tends to facilitate multidrug mutational resistance. Moreover, disruption in mismatch repair systems not only increases mutation but also facilitates hyperrecombination (J. E. LeClerq et al., Letter, Science 289:391–392, 2000). This may contribute to a frequent reacquisition of the hexA+ alleles from other cells, once the adaptive bottleneck has been crossed, thereby limiting the biological cost necessarily associated with hypermutation (risk of deadaptive, deleterious mutations). On the other hand, hyperrecombination may influence the spread of mutated genes among bacterial communities. The possibility that some antibiotics may influence the evolvability of bacterial populations is becoming another key reason to optimize the use of these drugs in human communities.

Acknowledgments

S. pneumoniae strains R800 and R310 were kindly provided by J. P. Claverys (Toulouse, France).

This work was supported by the grants BIO4-CT98-0424 from the European Commission and 08.3/0028.3/98 from Comunidad de Madrid. M.-R. Baquero was the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship (02/0067/1998) from the Consejería de Educación de la Comunidad de Madrid. R. del Campo is the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship (09/447639.6/00) from the Comunidad de Madrid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alloing, G., B. Martin, C. Granadel, and J. P. Claverys. 1998. Development of competence in Streptococcus pneumoniae: pheromone autoinduction and control of quorum sensing by oligopeptide permease. Mol. Microbiol. 29:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coffey, T. J., M. Daniels, L. K. McDougal, C. G. Dowson, F. C. Tenover, and B. G. Spratt. 1995. Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with high-level resistance to expanded-spectrum cephalosporins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1306–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dowson, C. G, A. Hutchison, J. A. Brannigan, R. C. George, D. Hansman, J. Liñares, A. Tomasz, J. M. Smith, and B. G. Spratt. 1989. Horizontal transfer of penicillin-binding protein genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:8842–8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granizo, J. J., L. Aguilar, J. Casal, C. García-Rey, R. Dal-Re, and F. Baquero. 2000. Streptococcus pneumoniae resistance to erythromycin and penicillin in relation to macrolide consumption in Spain (1986–1997). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:767–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grebe, T., and R. Hakenbeck. 1996. Penicillin-binding proteins 2b and 2x of Streptococcus pneumoniae are primary resistance determinants for different classes of beta-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:829–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hooper, D. C. 2001. Emerging mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:337–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humbert, O., M. Prudhomme, R. Hakenbeck, C. G. Dowson, and J. P. Claverys. 1995. Homeologous recombination and mismatch repair during transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae: saturation of the Hex mismatch repair system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:9052–9056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laible, G., B. G. Spratt, and R. Hakenbeck. 1991. Interspecies recombinational events during the evolution of altered PBP2x genes in penicillin-resistant clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Mol. Microbiol. 5:1993–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mouz, N., A. M. Guilmi, E. Gordon, R. Hakenbeck, O. Dideberg, and T. Vernet. 1999. Mutations in the active site of penicillin-binding protein PBP2x from Streptococcus pneumoniae: role in the specificity for beta-lactam antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 274:19175–19180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 11th informational supplement. M11–S11. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 11.Negri, M. C., M. I. Morosini, E. Loza, and F. Baquero. 1994. In vitro selective antibiotic concentrations of beta-lactams for penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae populations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:122–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oliver, A., R. Cantón, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blázquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prudhomme, M., V. Mejean, B. Martin, and J. P. Claverys. 1991. Mismatch repair genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae: HexA confers a mutator phenotype in Escherichia coli by negative complementation. J. Bacteriol. 173:7196–7203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radman, M., I. Matic, and F. Taddei. 1999. Evolution of evolvability. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 870:146–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Samrakandi, M. M., and F. Pasta. 2000. Hyperrecombination in Streptococcus pneumoniae depends on an atypical mutY homologue. J. Bacteriol. 182:3353–3360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tait-Kamradt, A., T. Davies, P. C. Appelbaum, F. Depardieu, P. Courvalin, J. Petitpas, L. Wondrack, A. Walker, M. R. Jacobs, and J. Sutcliffe. 2000. Two new mechanisms of macrolide resistance in clinical strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae from Eastern Europe and North America. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3395–3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]