Abstract

Grepafloxacin, a 5-methyl-7-piperazinyl-3"-methyl analogue of ciprofloxacin, was used to obtain stepwise-selected mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae 7785. Analysis of the quinolone resistance-determining regions of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes in these mutants revealed that gyrA mutations preceded those in parC. Given that ciprofloxacin (5-H,7-piperazinyl) and AM-1121 (5-H,7-piperazinyl-3"-methyl) both act through topoisomerase IV, we conclude that the 5-methyl group of grepafloxacin favors gyrase in S. pneumoniae.

In recent years, fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin, grepafloxacin, gatifloxacin, moxifloxacin, and sparfloxacin have been introduced for the treatment of pneumonia and other diseases due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, a major gram-positive pathogen (2, 26). By interfering with DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV, two essential enzymes that function through a double-stranded DNA break (3, 7, 8, 13, 31), these agents are also effective against S. pneumoniae isolates that exhibit decreased susceptibility to penicillins and macrolides (29).

The precise mode of action of a quinolone against S. pneumoniae depends on its molecular structure (20, 23). One group of quinolones, whose archetype is ciprofloxacin and which includes levofloxacin, norfloxacin, pefloxacin, and trovafloxacin, selects first-step mutants altered in the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) of parC or parE, indicating that topoisomerase IV is the intracellular target (5, 9, 11, 16, 18, 24, 28). A second group includes sparfloxacin and NSFQ-105 and selects first-step gyrA QRDR mutants, implying that gyrase is the preferred target (1, 5, 20, 24). Clinafloxacin, gatifloxacin, gemifloxacin, and moxifloxacin select gyrA mutants at a rather low frequency (6, 10, 21) and seem to act through both enzymes, so they are called dual-targeting agents. Efforts to understand drug targeting have indicated a role for the C-7 and C-8 substituents (1, 6), but little is known about the effects of C-5 substitution. We realized that grepafloxacin, a simple 5-methyl-7-piperazinyl-3"-methyl derivative of ciprofloxacin (Fig. 1),could be informative. Previous work has shown that gyrA or parC mutations in S. pneumoniae raised the MIC of grepafloxacin some two- to fourfold, but no definite target assignment was made (30). Here we examine grepafloxacin action in S. pneumoniae by using defined mutants, by characterizing stepwise-selected mutants, and by using recombinant enzymes.

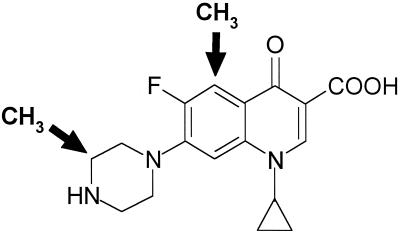

FIG. 1.

Grepafloxacin structure is related to that of ciprofloxacin through the addition of methyl groups at the C-3" position of the piperazine ring and at C-5 (arrows).

(Part of this study was presented at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, San Francisco, Calif., 26 to 29 September 1999.)

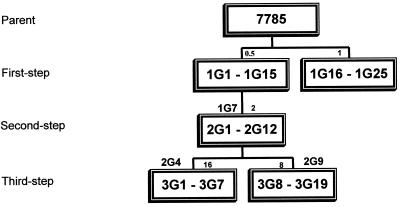

Approximately 5 × 109 CFU of susceptible isolate 7785 (18) was spread on brain heart infusion plates containing 10% horse blood and grepafloxacin at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 μg/ml, i.e., one and two times the MIC for the parent strain (Fig. 2).Mutants appeared after 48 h of aerobic incubation at 37°C. Mutants 1G1 to 1G15 and 1G16 to 1G25 from the two independent drug challenges were studied further. Second-step mutants 2G1 to 2G12 were obtained similarly using strain 1G7 as the parent strain and grepafloxacin at a concentration of 2 μg/ml, i.e., two times the MIC. Third-step mutants were selected from strains 2G4 and 2G9 using the drug at concentrations of 16 and 8 μg/ml, respectively (Fig. 2). Mutational frequencies for the first- and second-step selections ranged between 1.2 × 10−7 and 2.1 × 10−8. For the third-step selections, they were between 2.2 × 10−8 and 7.1 × 10−8. The gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE QRDRs were amplified by PCR and examined by HinfI restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) and DNA sequence analysis (18-21).

FIG. 2.

Relationships of S. pneumoniae mutants selected stepwise with grepafloxacin. Single numbers above the boxes indicate the concentrations of grepafloxacin (in micrograms per milliliter) used in each step of selection. The strains used in stepwise selection are indicated above the boxes (1G7, 2G4, 2G9).

Table 1 summarizes the properties of parental strain 7785, its derivatives 1C1 to 2S4 bearing defined quinolone resistance mutations (21), and the various stepwise-selected mutants. The MIC of grepafloxacin for strain 7785 was 0.5 μg/ml, i.e., fourfold lower than that of ciprofloxacin, with the difference attributed to greater hydrophobicity (27, 30, 32). The MICs of grepafloxacin for defined parC strains 2C6 and 2C7 and gyrA mutants 1S1 and 1S4 exhibited two- and fourfold increases, the inverse of the effect observed with ciprofloxacin (Table 1). parC-gyrA strains were highly resistant to both drugs. These data are consistent with earlier studies (30).

TABLE 1.

Fluoroquinolone resistance profiles of isogenic S. pneumoniae mutants

| Straina | MIC (μg/ml) ofb:

|

Mutation(s) in the QRDR ofc:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GREP | CIP | GyrA | ParC | GyrB | ParE | |

| 7785 | 0.5 | 2 | ||||

| 1C1 | 0.5 | 4 | None | None | None | None |

| 2C6 | 1 | 8 | None | S79Y | None | None |

| 2C7 | 1 | 8 | None | S79F | None | None |

| 1S1 | 2 | 2 | S81F | None | None | None |

| 1S4 | 2 | 2 | S81Y | None | None | None |

| 3C4 | 16 | 64 | S81Y | S79Y | None | None |

| 2S1 | 16 | 32-64 | S81F | S79Y | None | None |

| 2S4 | 16 | 32 | S81F | D83N | None | None |

| 1G7d | 1 | 2 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G9 | 1 | 2 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G12 | 1 | 2 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G14 | 1 | 2 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G17 | 2-4 | 4 | S81F | None | None | None |

| 1G18 | 2-4 | 4 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G20 | 2-4 | 4 | None | None | None | None |

| 1G22 | 2-4 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 1G23 | 4-8 | 4-8 | S81Y | None | None | None |

| 1G25 | 2-4 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G1 | 4 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G2 | 4 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G3 | 4-8 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G4d | 4-8 | 4 | S81F | None | None | None |

| 2G5 | 4-8 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G6 | 4-8 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 2G8 | 4 | 4 | None | None | ||

| 2G9d | 4 | 4 | S81F | None | None | None |

| 2G10 | 4 | 4 | None | None | ||

| 2G11 | 4 | 4 | S81Y | None | ||

| 2G12 | 4 | 4 | + | − | ||

| 3G1 | 32 | 64 | S81F | D83N | None | None |

| 3G3 | 64 | 64-128 | S81F | D83Y | None | None |

| 3G10 | 32 | 64 | S81F | S79F | None | None |

| 3G18 | 64 | 64-128 | S81F | S79Y | None | None |

Mutations in strains selected with ciprofloxacin (C) and sparfloxacin (S) have been described previously (21). In strains selected with grepafloxacin (G), the GyrA changes were S81F (TCC to TTC) and S81Y (TCC to TAC) and the ParC mutations were S79F (TCT to TTT), S79Y (TCT to TAT), D83N (GAT to AAT), and D83Y (GAT to TAT).

GREP, grepafloxacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin.

+ or − indicates the presence or absence, respectively, of a mutation detected by HinfI RFLP analysis of PCR products (18, 21).

Strain used in the stepwise selection of grepafloxacin-resistant mutants.

The MICs of grepafloxacin for first-, second-, and third-step mutants were 1 to 8, 4 to 8, and 32 to 64 μg/ml, respectively (Table 1). To uncover common resistance mutations at codon 81 in gyrA and at codon 79 in parC, PCR products were generated and routinely screened by HinfI digestion (21). Among the first-step mutants 1G1 to 1G25, PCR products of strains 1G17, 1G22, 1G23, and 1G25 had lost a HinfI site overlapping codon 81 of gyrA, indicating the presence of a resistance mutation at this position. There was no change in the parC HinfI cleavage pattern for any of the first-step mutants. DNA sequence analysis of gyrA (codons 53 to 166), parC (codons 42 to 151), gyrB (codons 378 to 506), and parE (codons 405 to 477) QRDRs (20) of mutants 1G17 and 1G23 revealed the presence of S81F and S81Y GyrA changes. No changes were found in the four QRDR sequences of strains 1G7, 1G9, 1G12, 1G14, 1G18, and 1G20 (Table 1). Thus, the grepafloxacin resistance of first-step mutants involves gyrase changes or another mechanism, possibly efflux, or conceivably mutations elsewhere in topoisomerase genes.

HinfI RFLP analysis of second-step mutants 2G1 to 2G12 revealed that nine had acquired a gyrA codon 81 mutation and that none had parC codon 79 alterations. DNA sequence analysis confirmed the presence of S81F or S81Y GyrA changes in strains 2G4, 2G9, and 2G11 (Table 1). All 19 third-step mutants carried a parC mutation. Thus, except for 3G1 and 3G3, HinfI RFLP analysis showed that the other 17 third-step mutants had acquired an alteration in parC, shown for strains 3G10 and 3G18 to encode S79F and S79Y ParC changes, respectively. DNA sequencing demonstrated that strains 3G1 and 3G3 had acquired mutations encoding D83N and D83Y changes in ParC. The uniform selection of mutations first in gyrA and then in parC (Table 1) indicates that gyrase is the primary target and topoisomerase IV is the secondary target of grepafloxacin in S. pneumoniae, the inverse of what was observed with ciprofloxacin.

Using recombinant S. pneumoniae 7785 topoisomerases, we found that the drug concentrations causing 50% inhibition of DNA supercoiling by gyrase in vitro were 160 and 80 μM for grepafloxacin and ciprofloxacin, respectively. The drug concentrations causing 50% inhibition of kinetoplast DNA decatenation by topoisomerase IV were 10 to 20 μM for both drugs (data not shown). Other studies have reported similar findings (4, 14, 17, 22). In DNA cleavage assays for gyrase and topoisomerase IV, both drugs caused 25% linearization of input DNA at 80 and 2.5 μM, respectively. Topoisomerase IV is therefore the more sensitive quinolone target in vitro.

Mutant gyrase and topoisomerase IV enzymes have been expressed from ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates and shown to be ∼2- and 3- to 5-fold less sensitive than the wild type to catalytic inhibition by grepafloxacin (15). Leaving aside the fact that inhibition was studied rather than DNA cleavage (the relevant lesion), there are difficulties in that the enzymes used had low specific activities, were incompletely characterized at the sequence level, and were derived from nonisogenic strains. Similar to previous work with sparfloxacin and ciprofloxacin (23), we found that gyrase and topoisomerase IV complexes bearing a single validated S81F GyrA and S79F ParC change were >32- and >80-fold less effective in grepafloxacin-stimulated DNA cleavage than were the wild-type enzymes (data not shown). By contrast, the MICs of grepafloxacin for strains 1S1 and 2C7, expressing S81F GyrA and S79F ParC, exhibited only four- and twofold increases (Table 1). Evidently, in these strains, the full effect of the resistance mutation is moderated by drug action on the other topoisomerase target. These results and those from analysis of stepwise-selected mutants indicate that both gyrase and topoisomerase IV contribute as intracellular targets of grepafloxacin, with a preference for gyrase.

Selection of first-step gyrA mutants, but an in vitro target preference for topoisomerase IV, is a feature of several quinolones (1, 23). On the basis of recent sparfloxacin studies, two explanations can be discounted. First, the primary intracellular target does not depend on the selective pressure: first-step gyrA mutants are selected by sparfloxacin at one, four, and eight-to-sixteen times the MIC (5, 20, 25), in accord with the poison mechanism of quinolone action (12). Second, first-step gyrA mutants do not carry an additional undetected non-QRDR mutation in topoisomerase IV responsible for resistance (14): strains 1S1 and 1S4, selected with sparfloxacin and resistant to grepafloxacin (Table 1), express wild-type topoisomerase IV proteins (23). We prefer a model in which drug-dependent differences in the formation, repair, or processing of cleavable complexes in vivo can override the in vitro enzyme preference to determine the killing pathway (23).

Grepafloxacin has a structure identical to that of ciprofloxacin except for the addition of a methyl group at C-5 and at the C-3" position of the 7-piperazinyl ring (Fig. 1). Ciprofloxacin and its 5-H-7-piperazinyl-3"methyl derivative (AM-1121) act through topoisomerase IV in S. pneumoniae (6). Therefore, it appears the C-5 methyl substituent of grepafloxacin, by changing steric, hydrophobic, or polar properties, favors the targeting of gyrase in S. pneumoniae. Sparfloxacin, which carries an amino group at C-5 in addition to the C-7 and C-8 substituents, also acts through gyrase (20) but so do the C-5-H quinolones, moxifloxacin and NSFQ-105 (1, 25). We conclude that quinolone targeting in S. pneumoniae is governed by a series of structure-activity relationships involving moieties at C-5 as well as at the C-7 and C-8 positions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Andrew Moult for his comments on the manuscript.

J.E.M. and this work were supported by a project grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alovero, F. L., X.-S. Pan, J. E. Morris, R. H. Manzo, and L. M. Fisher. 2000. Engineering the specificity of antibacterial fluoroquinolones: benzenesulfonamide modifications at C-7 of ciprofloxacin change its primary target in Streptococcus pneumoniae from topoisomerase IV to gyrase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:320-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartlett, J. G., and L. M. Grundy. 1995. Community-acquired pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 333:1618-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drlica, K., and X. Zhao. 1997. DNA gyrase, topoisomerase IV, and the 4-quinolones. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:377-392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez-Moreira, E., D. Balas, I. Gonzalez, and A. G. de la Campa. 2000. Fluoroquinolones inhibit preferentially Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA topoisomerase IV than DNA gyrase native proteins. Microb. Drug Resist. 6:259-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukuda, H., and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Primary targets of fluoroquinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:410-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda, H., R. Kishii, M. Takei, and M. Hosaka. 2001. Contributions of the 8-methoxy group of gatifloxacin to resistance selectivity, target preference, and antibacterial activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1649-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gellert, M., K. Mizuuchi, M. H. O'Dea, T. Itoh, and J.-I. Tomizawa. 1977. Nalidixic acid resistance: a second genetic character involved in DNA gyrase activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:4772-4776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gellert, M., K. Mizuuchi, M. H. O'Dea, and H. A. Nash. 1976. DNA gyrase: an enzyme that introduces superhelical turns into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 73:3872-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gootz, T. D., R. Zaniewski, S. Haskell, B. Schmieder, J. Tankovic, D. Girard, P. Courvalin, and R. J. Polzer. 1996. Activity of the new fluoroquinolone trovafloxacin (CP-99,219) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae selected in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2691-2697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heaton, V. J., J. E. Ambler, and L. M. Fisher. 2000. Potent antipneumococcal activity of gemifloxacin is associated with dual targeting of gyrase and topoisomerase IV, an in vivo target preference for gyrase, and enhanced stabilization of cleavable complexes in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3112-3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Janoir, C., V. Keller, M.-D. Kitzis, N. J. Moreau, and L. Gutmann. 1996. High-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae requires mutations in parC and gyrA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2760-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreuzer, K. N., and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1979. Escherichia coli mutants thermosensitive for deoxyribonucleic acid gyrase A subunit: effects on deoxyribonucleic acid replication, transcription, and bacteriophage growth. J. Bacteriol. 140:424-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuuchi, K., L. M. Fisher, M. H. O'Dea, and M. Gellert. 1980. DNA gyrase action involves the introduction of transient double-strand breaks into DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:1847-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey, I., and J. George. 1999. Activities of fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae type II topoisomerases purified as recombinant proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:2579-2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrissey, I., and J. T. George. 2000. Purification of pneumococcal type II topoisomerases and inhibition by gemifloxacin and other quinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45(Suppl. 1):101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muñoz, R., and A. G. De La Campa. 1996. ParC subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a primary target of fluoroquinolones and cooperates with DNA gyrase A subunit in forming resistance phenotype. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2252-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Onodera, Y., Y. Uchida, M. Tanaka, and K. Saito. 1999. Dual inhibitory activity of sitafloxacin (DU-6859a) against DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:533-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pan, X.-S., J. Ambler, S. Mehtar, and L. M. Fisher. 1996. Involvement of topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase as ciprofloxacin targets in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2321-2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan, X.-S., and L. M. Fisher. 1996. Cloning and characterization of the parC and parE genes of Streptococcus pneumoniae: role in fluoroquinolone resistance. J. Bacteriol. 178:4060-4069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pan, X.-S., and L. M. Fisher. 1997. Targeting of DNA gyrase in Streptococcus pneumoniae by sparfloxacin: selective targeting of gyrase or topoisomerase IV by quinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:471-474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pan, X.-S., and L. M. Fisher. 1998. DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV are dual targets of clinafloxacin action in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2810-2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan, X.-S., and L. M. Fisher. 1999. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA gyrase and topoisomerase IV: overexpression, purification, and differential inhibition by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1129-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan, X.-S., G. Yague, and L. M. Fisher. 2001. Quinolone resistance mutations in Streptococcus pneumoniae GyrA and ParC proteins: mechanistic insights into quinolone action from enzymatic analysis, intracellular levels, and phenotypes of wild-type and mutant proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3140-3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perichon, B., J. Tankovic, and P. Courvalin. 1997. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1166-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pestova, E., J. J. Millichap, G. A. Noskin, and L. R. Peterson. 2000. Intracellular targets of moxifloxacin: a comparison with other fluoroquinolones. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piddock, L. J., M. Johnson, V. Ricci, and S. L. Hill. 1998. Activities of new fluoroquinolones against fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens of the lower respiratory tract. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2956-2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stewart, B. A., A. P. Johnson, and N. Woodford. 1999. Relationship between mutations in parC and gyrA of clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae and resistance to ciprofloxacin and grepafloxacin. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:1103-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tankovic, J., B. Perichon, J. Duval, and P. Courvalin. 1996. Contribution of mutations in gyrA and parC genes to fluoroquinolone resistance of mutants of Streptococcus pneumoniae obtained in vivo and in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2504-2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thornsberry, C., P. T. Ogilvie, H. P. Holley, and D. F. Sahm. 1998. In vitro activity of grepafloxacin and 25 other antimicrobial agents against Streptococcus pneumoniae: correlation with penicillin resistance. Clin. Ther. 20:1179-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varon, E., C. Janoir, M.-D. Kitzis, and L. Gutmann. 1999. ParC and GyrA may be interchangeable initial targets of some quinolones in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:302-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, J. C. 1996. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:635-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiedemann, B., and P. Heisig. 1997. Antibacterial activity of grepafloxacin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 40(Suppl. A):19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]