Abstract

The trisubstituted pyrrole 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(1-methylpiperidine-4-yl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]pyridine (compound 1) is a potent inhibitor of cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinases from Apicomplexan protozoa and displays cytostatic activity against Toxoplasma gondii in vitro. Compound 1 has now been evaluated against T. gondii infections in the mouse and appeared to protect the animals when given intraperitoneally at 50 mg/kg twice daily for 10 days. However, samples from brain, spleen, and lung taken from infected treated mice revealed the presence of parasites after cessation of administration of compound 1, indicating that a transient asymptomatic parasite recrudescence occurs in all survivors. The ability of mice to control Toxoplasma infection after compound 1 treatment has been terminated suggested that the mouse immune system plays a synergistic role with chemotherapy in controlling the infection. To explore this possibility, gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-knockout mice were infected with parasites and treated with compound 1, and survival was compared to that of normal mice. IFN-γ-knockout mice were protected against T. gondii throughout the treatment phase but died during the posttreatment phase in which peak recrudescence was observed in treated immunocompetent mice. These data suggest that an IFN-γ-dependent immune response was essential for controlling and resolving parasite recrudescence in mice treated with compound 1. In addition, when compound 1-cured immunocompetent mice were rechallenged with a lethal dose of T. gondii, all survived (n = 32). It appears that the cytostatic nature of compound 1 provides an “immunization” phase during chemotherapy which allows the mice to survive the recrudescence and any subsequent challenge with a lethal dose of T. gondii.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite that infects a broad range of warm-blooded animals, including humans. Toxoplasma infections in humans are generally benign, but significant morbidity and mortality are frequent in congenital infections and in immunocompromised hosts such as cancer and transplant patients and patients with AIDS (9, 13–15). The clinical manifestation of toxoplasmosis in AIDS patients and other immunocompromised individuals includes development of encephalitis, which generally culminates in focal brain disease (12, 13). The reactivation of latent infection or tissue cysts is primarily responsible for the development of toxoplasmic encephalitis. The incidence of this is about 12% at the 1-year mark in patients whose CD4 counts have dropped below 200 per mm3 (1, 6, 14).

Currently, the recommended treatment for toxoplasmosis in humans is pyrimethamine in synergistic combination with sulfonamide. Treatment with this combination often includes folinic acid to minimize hematological toxicity (2). The pyrimethamine-sulfonamide regimen is often effective in both immunocompetent and immunocompromised individuals, including AIDS patients. However, significant toxicity is common, particularly in immunodeficient individuals, resulting in discontinuation of one or both drugs, particularly the sulfonamide (5, 8). Some more recent pharmacologic approaches have involved the use of other antibiotics such as clindamycin or atovaquone instead of sulfadiazine, but none of these combinations are superior to the pyrimethamine-sulfonamide standard (5). There is therefore a need for continued research aimed at the identification and development of new compounds for the treatment of toxoplasmosis either in monotherapy regimens or in combination with existing drugs.

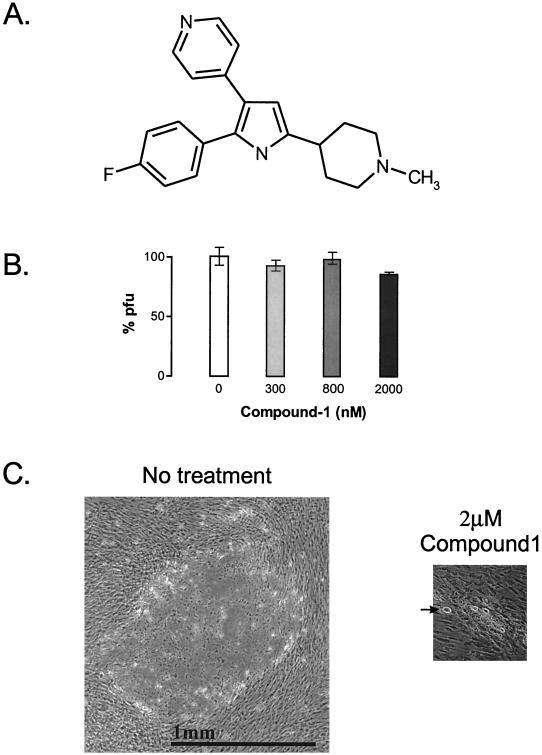

In the present study, we have evaluated the efficacy of compound 1 (Fig. 1A), a novel and selective inhibitor of protozoan cyclic GMP (cGMP)-dependent protein kinases (A. Gurnett et al., submitted for publication; R. Donald et al., submitted for publication), against a highly virulent form of T. gondii (RH strain) both in vitro and in vivo, using a murine model of acute toxoplasmosis. Our in vitro assays which assess parasite survival in human fibroblasts were used to determine if compound 1 was cytostatic or cytocidal. In vivo, we have established the dosing frequency required to resolve murine toxoplasmosis and also have determined whether monotherapy with compound 1 is dependent upon the immune system.

FIG. 1.

(A) Chemical structure of the trisubstituted pyrrole 4-[2-(4-fluorophenyl)-5-(1-methylpiperidine-4-yl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]pyridine (compound 1; molecular weight = 335.4). (B) Lack of effect of compound 1 on parasite viability. Parasites were inoculated onto T-25 HFF cell monolayers in triplicate, and treatment was initiated 8 h later. The numbers of plaques appearing after 7 days of continuous treatment are compared with those in an untreated control group (100% PFU). Error bars indicate standard errors. (C) Morphology of Toxoplasma plaques formed in HFF cell monolayers following 7 days of growth in the absence (no treatment) or continuous presence of 2 μM compound 1, shown at the same level of magnification. Foci formed with 2 μM compound 1 (≈10 times the IC50) were approximately 10-fold smaller and contained tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and refractile bodies (arrow) that were identified as cysts in immunofluorescence assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

The virulent T. gondii strain RH, stably expressing β-galactosidase from Escherichia coli (16, 23), was used throughout this study. In addition, the P strain, a clonal isolate from strain ME49 (27) of T. gondii, was used in the vaccination-challenge studies. Tachyzoites of T. gondii were maintained by serial passage in confluent monolayers of human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs) in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 1 to 2% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 25 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 50 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml. For routine maintenance, HFFs were passaged at a 1:4 dilution in T-175 flasks containing 50 ml of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 25 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 50 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml. All tissue culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, Calif.

Colorimetric assay for growth inhibition.

HFFs were plated in 96-well plates in 150 to 200 μl of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium lacking phenol red and allowed to reach confluency in 5% CO2. The spent medium was aspirated and replaced with 150 μl of MEM without phenol red containing 103 tachyzoites of T. gondii/well. Various concentrations (0 to 1,000 ng/ml) of compound 1 (synthesized by the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, N.J.) were added, using triplicate wells for each concentration, and incubation was carried out for 5 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. Twenty microliters of the β-galactosidase substrate 4-chlorophenol red–β-d-galactopyranoside (CPRG) (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) per well was added to give a final concentration of 100 μM, and the plates were returned to the incubator. After incubation with CPRG (2 to 4 h), the plates were analyzed (570 nm) on a Rainbow Thermo microtiter plate reader (TECAN, Durham, N.C.), at a time when wells containing parasites incubated in the absence of inhibitor had reached an absorbance of 1.0 (16).

To assess the toxicity of compound 1 to HFFs, cells were plated in 96-well plates at 103/well and allowed to adhere overnight prior to addition of compound. Cultures were incubated for 5 days at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Viability was assessed using the Cell-Titer 96 Aqueous One solution cell-proliferating assay (Promega, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

[3H]uracil uptake and plaque assays.

A modified [3H]uracil uptake assay (18) was also used to measure parasite growth inhibition. The incorporation of [5,6-3H]uracil (NEN Life Science Products, Inc., Boston, Mass.) (33 Ci/mmol), a parasite-specific metabolic label, was measured in parasite cultures grown in 96-well Cytostar-T scintillation culture plates (Amersham/Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). By permitting real-time, noninvasive monitoring of radiolabel incorporation into cell monolayers, Cytostar-T plates greatly enhance the utility of the conventional [3H]uracil uptake assay. HFF cells were initially seeded in the Cytostar-T microplates and allowed to grow to confluency. After removal of medium, twofold serial dilutions of the compound were distributed across the plate in duplicate, followed by the addition of 104 parasites and 2 μCi of [3H]uracil to each well. After 48 h of incubation, the radioactivity of the plates was counted in a 1450 Microbeta Plus liquid scintillation counter (Wallac, Gaithersburg, Md.). Fifty percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were determined from plots of samples run in duplicate, using nonlinear regression (curve fit) analysis from GraphPad Prism (version 3).

For plaque assays, T. gondii tachyzoites were incubated with confluent HFF monolayers in T-25 flasks containing 10 ml of MEM (20) in the presence or absence of up to 2 μM compound 1. Plaques were inspected 7 to 10 days later with an inverted microscope. Parasite viability was determined by counting plaques after fixing infected monolayers with methanol and staining with crystal violet (20). The presence of T. gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and tissue cysts growing within plaques in treated cultures was detected by immunofluorescence, using stage-specific antisera (P30 and P36 monoclonal antibodies [24]) and lectin reagents (Dolichos biflorus agglutinin [10]).

Animals and in vivo efficacy studies.

Mice were conventionally housed, within a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care in static microisolator cages with corncob bedding and provided ad libitum feed (catalog no. 7012; Teklad, Madison, Wis.) and reverse-osmosis-purified water. All procedures were performed in accordance with the highest standards for the humane handling, care, and treatment of research animals and were approved by the Merck Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Procedures for the care and use of research animals at Merck Research Laboratories meet or exceed all applicable local, national, and international laws and regulations.

Freshly released tachyzoites of T. gondii were collected, washed in MEM, and counted. Female wild-type mice of the C57BL/6J strain and homozygous gamma interferon (IFN-γ)-disrupted (GKO) mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, Maine) were inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 103 to 3 × 103 T. gondii tachyzoites diluted in a final volume of 500 μl of MEM. Parasite titers used in inoculating mice were always confirmed by plaque assays. Compound 1 was dissolved in water and administered in 100-μl doses by intraperitoneal injections starting 24 h after parasite inoculation. Mice were monitored twice daily for clinical evidence of toxoplasmosis and mortality throughout the experimental period.

Quantitation of parasite loads in mouse tissues.

To determine the kinetics of T. gondii infection and curative rates of compound 1, samples of spleen, brain, lung, and peritoneal fluid were recovered from control and treated animals (three mice per group) at different days after inoculation. Mice were euthanized by exposure to CO2, and recovered tissues were washed two times in phosphate-buffered saline and suspended in 5 ml of MEM. For peritoneal samples, the peritoneal cavity was lavaged with 5 ml of MEM to recover any parasites within the cavity. Brain, spleen, and lung samples were each homogenized by direct pressure in 5 ml of MEM using Whirl Pack bags (Environmental Monitoring Systems, Charleston, N.C.). From each organ suspension, 100 μl was added to confluent HFF monolayers (100 μl) and serially diluted twofold across the plate in triplicate. After 5 to 7 days at 37°C, the plates were examined under an inverted microscope and the presence of parasite plaques was recorded for each well. CPRG was added, and β-galactosidase activity was determined as described above to confirm the plaque observations. The final parasite titer was considered to be the final dilution for which the monolayer contained at least one parasite (19), and all dilution factors were taken into account to obtain the final number of organisms per organ. Tissue samples from uninfected animals were included to serve as background signals for β-galactosidase activity.

Assay for levels of compound 1 in plasma.

The concentration of compound 1 in serum following a single intraperitoneal dose of 50 mg/kg in C57BL/6 female mice was evaluated using a cGMP-dependent protein kinase bioassay. Blood was collected in Microtainer separator tubes (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 18, and 24 h after dosing from six mice per time point. After centrifugation, 100 μl of plasma was combined with 100 μl of water and 25 μl of 50% acetonitrile and mixed gently by shaking. The samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 2,000 × g at room temperature. The liquid phase containing compound 1 was removed, evaporated to dryness, and stored at −20°C or reconstituted in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide. Diluted samples from plasma extracts were incubated with purified recombinant T. gondii cGMP-dependent kinase (Donald et al., submitted) to generate IC50s for the determination of the concentration of compound 1 in plasma. Plasma aliquots from untreated mice were spiked with different concentrations of compound 1, extracted as described above, and used to generate standard curves.

cGMP-dependent protein kinase activity was assayed using 96-well Multiscreen phosphocellulose plates (MAPH-NOB; Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) to capture 33P-phosphorylated kemptide peptide substrate. Kinase reactions were carried out in 40-μl volumes containing 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μM cGMP, 250 μM kemptide, 1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml, 20 μM ATP, 0.01 μM [γ-33P]ATP (NEN/DuPont) (3,000 Ci/mmol), and samples of serially diluted mouse plasma. The reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme, and reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 60 min. Dilutions of enzyme that ensured that reactions were linear over a time course of up to 2 h were used. Reactions were terminated by addition of phosphoric acid (2.5 mM final concentration) before samples were applied to a phosphocellulose plate mounted on a vacuum manifold. Wells were washed in 75 mM phosphoric acid and dried, and radiolabeled peptide was detected by scintillation counting on a 1450 Microbeta scintillation counter (Wallac).

Statistical analysis.

Accelerated failure-time regression models were fit to the data in each of the survival studies to account for the survival nature of the data and the presence of censored times, since some animals were still alive at the end of the studies. The underlying statistical assumptions of Gaussian distribution and equal variances were reasonably met in each case. Follow-up comparisons were based on these models to assess significance, using the common 5% cutoff, and to express magnitudes of effects in terms of percent change in median survival.

RESULTS

Inhibition of intracellular replication of T. gondii in vitro.

Using the activity of the transgenic β-galactosidase marker as an estimate of parasite activity (23), the trisubstituted pyrrole compound 1 (Fig. 1A) displayed a dose-dependent inhibition of T. gondii tachyzoites replicating inside HFFs, with an IC50 of 210 ± 100 nM (n = 5 experiments). Using the metabolic [3H]uracil uptake assay, we obtained an IC50 of 230 ± 90 nM (n = 7 experiments). Interestingly, at concentrations of compound 1 that were up to 10-fold above the IC50 (≤2 μM), parasite viability (assayed by the ability to form plaques) was not markedly affected (Fig. 1B). However, we noticed a dramatic reduction in plaque size that was proportional to the level of treatment; plaque diameter was reduced 10- to 15-fold in cultures exposed to 2 μM compound 1 for 1 week (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, unlike the clear lytic plaques formed in the absence of compound, the minute plaques formed with 2 μM compound 1 showed little evidence of cell lysis. Instead, these turbid foci contained slow-growing intracellular tachyzoites and bradyzoites as well as refractile cysts, as determined by staining with stage-specific antisera and lectin reagents (H. Wiersma and R. Donald, unpublished data). The suppression of lytic parasite growth by compound 1 was reversible. Replacement of the medium with medium lacking compound 1, after treatment for up to 7 days at 2 μM, resulted in complete lysis of HFF cell monolayers (not shown). Compound 1 was neither toxic nor inhibitory to proliferating or confluent monolayers of HFFs at concentrations of up to 10 μM.

In vivo activity of compound 1.

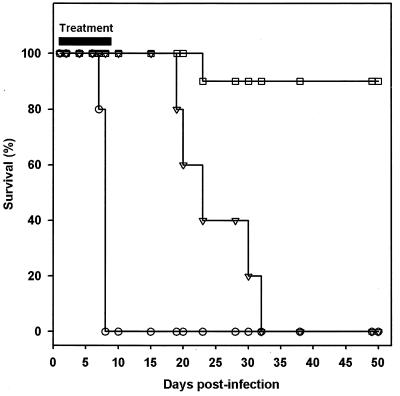

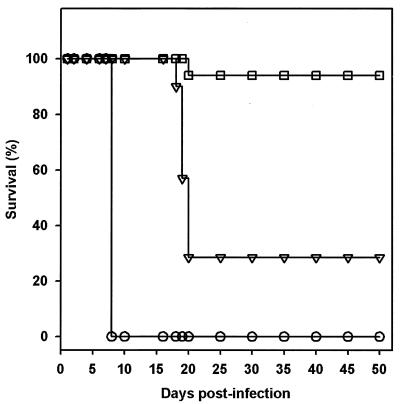

Assessment of the efficacy of compound 1 was performed with the mouse model of toxoplasmosis using C57BL/6J female mice inoculated intraperitoneally with 1 × 103 to 3 × 103 tachyzoites of T. gondii. Preliminary experiments conducted with single intraperitoneal daily doses of 10, 25, or 50 mg of compound 1 per kg resulted in recrudescence and death of mice after cessation of treatment. When 50 mg of compound 1 per kg was given as a twice-daily dose for 10 days, nearly 90% of the mice (89% ± 7%; n = 4 independent experiments) survived a dose of T. gondii that is lethal to control mice (P < 0.001 versus untreated animals). The results of a representative experiment are shown in Fig. 2. There was no evidence of clinical recrudescence in these cured mice for up to 12 months following treatment. In contrast, when compound 1 was given once daily for 10 days at 50 mg/kg, the mice were only partially protected, with 100% mortality observed by day 33 posttreatment. Untreated or placebo-treated animals succumbed to the infection by day 7 to 8 after inoculation with T. gondii tachyzoites. The prolonged survival observed in animals treated with 50 mg/kg once daily for 10 days was significant compared to that of untreated controls (P < 0.001). We did not observe any overt signs of compound 1-related toxicity in mice that were treated in this study.

FIG. 2.

Survival of mice infected with a virulent strain (RH) of T. gondii and treated with compound 1. Compound 1 was administered intraperitoneally at 50 mg/kg once daily (▿) or twice daily (□), starting 24 h after infection, for 10 days. Control animals (○) were injected with vehicle (sterile water) throughout the treatment period. Four independent trials were conducted using groups of at least 10 mice per treatment group, and results are presented as the percent survival from one representative trial.

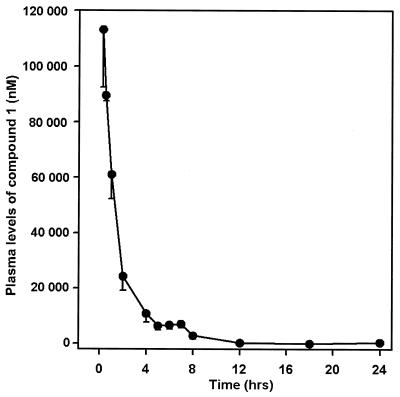

Administration of a single intraperitoneal dose of 50 mg of compound 1 per kg resulted in levels in plasma that were detectable by a cGMP-dependent protein kinase bioassay up to 24 h after dosing (Fig. 3). However, concentrations of compound 1 were below 100 ng/ml (300 nM) by the 8-h time point. The half-life was 1.8 h, with an average mean residence time of 2.7 h.

FIG. 3.

Concentration of compound 1 in plasma following a single intraperitoneal dose of 50 mg/kg in uninfected mice. Drug levels in plasma were obtained using a cGMP-dependent protein kinase bioassay. A plot of compound 1 concentration in plasma at various times after administration is shown as means ± standard errors for six mice for each time point.

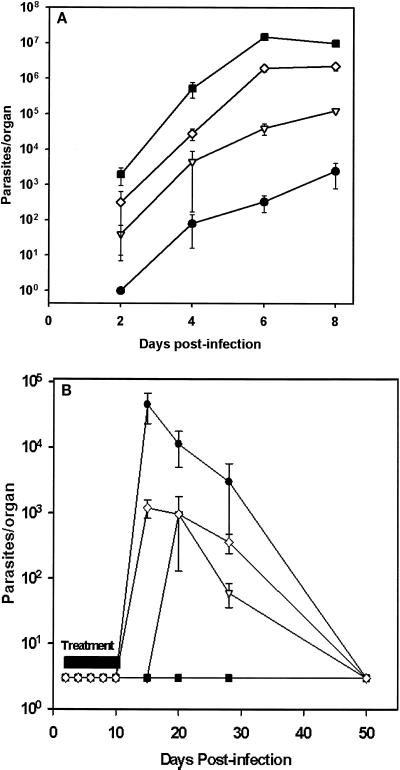

Determination of parasite load in mouse tissues.

Both in vitro and in vivo experiments were conducted with a transgenic RH strain of T. gondii expressing the β-galactosidase gene from E. coli (16, 23) to facilitate the determination of IC50s with in vitro-grown parasite cultures and to simplify the determination of parasite tissue load in infected mice. However, the utility of the β-galactosidase assay to determine parasite tissue burden was limited by low sensitivity and high background levels, particularly in spleen and lung homogenates. Accordingly, parasite foci or plaques formed on HFF monolayers after incubation with tissue homogenates were utilized as the primary indicator of parasite burden within the tissue. Parasites were detected in the spleen, peritoneal cavity, and lungs as early as day 2 postinfection, and parasitic loads progressively increased until the death of the untreated animals at day 7 to 8 (Fig. 4A). The appearance of T. gondii in the brain was delayed somewhat compared to that in the peritoneum, spleen, or lung. In infected mice that were treated with compound 1 at 50 mg/kg twice daily, parasites were undetectable throughout the 10-day treatment period in each of the tissues examined (Fig. 4B). Five days after cessation of therapy (15 days postinfection), parasites could be detected in the spleens and brains of treated animals. Significant parasite loads were also observed in the lungs of these animals by day 10 following cessation of treatment, indicating significant recrudescence in these animals. We were unable to detect T. gondii in the peritoneal cavities of compound 1-treated mice throughout the posttreatment phase. The parasite load in the spleens, brains, and lungs peaked within the first 5 to 10 days after cessation of compound 1 treatment. Thereafter the parasite load declined in these tissues, reaching undetectable levels by day 50 and day 80 after inoculation. Compound 1-treated animals did not exhibit any clinical signs of toxoplasmosis during the posttreatment phase despite significant tissue parasite loads early after cessation of treatment. Up to 10% of mice treated with compound 1 died within 10 to 25 days after cessation of treatment at 50 mg/kg twice daily. When these mice were sampled for T. gondii tissue load, large numbers of tachyzoites were identified only in the brains. In contrast, moribund or dead mice sampled during this period that had been treated with subcurative doses of compound 1 contained parasites in all tissues examined. In light of the observation that in vitro-grown parasites form cysts in the presence of cytostatic levels of compound 1, we also examined brain homogenates for evidence of tissue cysts. None were found either in the subpopulation of compound 1-treated moribund mice or in the larger population of cured long-term survivors sampled at up to 6 months after parasite inoculation.

FIG. 4.

Kinetics of parasite load in mice infected with tachyzoites of T. gondii. Infected mice were dosed at 24 h postinfection with vehicle (A) or compound 1 (B) twice daily for 10 days. Brain (•), lungs (▿), spleen (◊), and peritoneal fluid (▪) were recovered from control and treated mice (three mice per group) at various time intervals, and tissue parasites were quantitated using plaque assay as described in Materials and Methods. Results represent the total number of parasites per organ corrected according to the initial dilution. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Protection against T. gondii challenge infection.

Because compound 1 was able to protect the majority of C57/BL/6J mice indefinitely against a primary infection of T. gondii, we investigated the response of these mice to a secondary challenge of parasite. Compound 1-cured mice challenged 6 months later with an intraperitoneal injection of 1 × 103 to 2 × 103 RH strain organisms were able to survive this secondary infection (Fig. 5). By way of comparison, age-matched naive mice all succumbed to this infection within 8 days. A third group of mice that was “immunized” with tachyzoites of the avirulent P strain of T. gondii showed a 25 to 30% survival rate when challenged with the RH strain of T. gondii (P < 0.001; data from two experiments). Mice that were cured of primary toxoplasmosis with compound 1 and rechallenged at either 3, 6, or 9 months showed greater than a 90% survival rate (P < 0.001) following a secondary challenge with the same virulent RH strain of T. gondii. Figure 5 shows the results of a representative experiment in which mice were rechallenged 6 months after the primary infection or “vaccination” event.

FIG. 5.

Compound 1-cured mice are immune to a secondary T. gondii infection. The first group of mice (n = 12) was infected with 1 × 103 to 3 × 103 tachyzoites of T. gondii (RH strain) and cured with a twice-daily dose of 50 mg of compound 1 per kg (□). The second group of mice (n = 10) was infected with 5 × 103 tachyzoites of the avirulent P strain of T. gondii (▿), while the third age-matched group of mice (n = 5) served as uninfected controls (○). Each of the three groups of mice was challenged 6 months after the initial infections with 103 tachyzoites of T. gondii (RH strain), and survival was monitored. Two additional trials, with long-term survivors rechallenged at 3 months (n = 8) and at 9 months (n = 9) following the primary parasite inoculation, yielded protection frequencies of 100%.

Dependency of compound 1 efficacy on the mouse immune system.

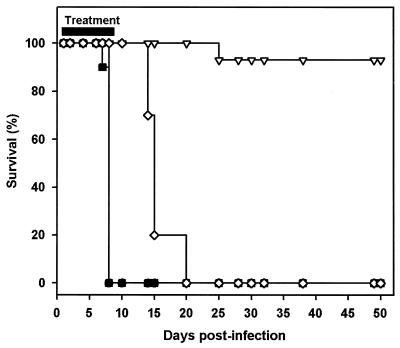

The ability of compound 1-cured mice to survive a secondary challenge of T. gondii suggested a role for the immune system in synergizing with chemotherapy to control primary toxoplasmosis. To delineate the requirements for an immune response in compound 1-mediated resolution of primary toxoplasmosis, the course of a T. gondii infection was monitored in GKO mice (26) versus wild-type mice. Previous studies (21, 22, 25) have shown that an IFN-γ-mediated immune response is essential for the control of murine toxoplasmosis. As shown in Fig. 6, T. gondii infections caused death in 100% of untreated wild-type and GKO mice by day 7 to 8 postinfection. In contrast, all infected GKO mice treated with compound 1 (50 mg/kg twice daily) survived throughout the 10-day treatment period. After termination of medication, mortality was observed in this group starting at day 13 and reached 100% by day 15 postinfection (Fig. 6). Survival of GKO mice that were treated with compound 1 was statistically significant (P < 0.001) compared with that of both untreated groups. As previously observed, compound 1 treatment produced greater than 90% survival (P < 0.001 versus all other groups) in T. gondii-infected wild-type mice throughout the experimental period.

FIG. 6.

Effects of compound 1 on the course of toxoplasmosis in wild-type versus GKO mice. Groups of 10 mice were infected with 1 × 103 to 3 × 103 tachyzoites of T. gondii and treated with a twice-daily dose of 50 mg of compound 1 per kg or vehicle control for 10 consecutive days. The ability to survive acute toxoplasmosis was assessed in wild-type mice treated with vehicle (•), GKO mice treated with vehicle (▪), GKO mice treated with compound 1 (◊), and wild-type mice treated with compound 1 (▿).

DISCUSSION

The antiparasitic activity of compound 1 was discovered in whole-cell screening assays, and the molecular target has been identified as a cGMP-dependent protein kinase in T. gondii and Eimeria tenella (Gurnett et al., submitted; Donald et al., submitted). We show in the present work that compound 1, a trisubstituted pyrrole, is cytostatic in cultured tachyzoites of T. gondii and cures murine toxoplasmosis following a monotherapy regimen of 50 mg/kg twice daily for 10 consecutive days.

Antitoxoplasma activity of compound 1 in vitro.

Evaluation of the inhibition of growth of T. gondii by compound 1 using the transgenic β-galactosidase marker or the traditional [3H]uracil uptake assay produced similar IC50s of ≈200 nM. While compound 1 is able to reduce parasite growth in HFF monolayers, it has a minimal effect on tachyzoite viability. Parasite growth and replication resume when compound 1 is removed from the culture medium. These observations suggest indirectly that the cGMP-dependent protein kinase target of compound 1, a putative signal transduction protein, may be involved in the control of parasite replication. The cytostatic nature of compound 1 could provide an opportunity for the development of chemotherapy-induced immunity in the host during treatment of protozoan parasites.

Resolution of acute murine toxoplasmosis and effects on parasite loads in tissues.

The results show that the clinical course of acute toxoplasmosis was altered by compound 1 when given at 10 to 50 mg/kg. However, only a twice-daily dosing of 50 mg/kg produced clinical and parasitological cures in greater than 90% of the treated animals. The observations that compound 1 was cytostatic towards T. gondii in vitro led us to investigate the presence of parasites in tissues of mice after cessation of treatment by sampling organs which are commonly affected in acute murine toxoplasmosis. The kinetics of toxoplasmosis in untreated mice were characterized by early involvement of the spleen, lung, and peritoneum (site of inoculation), with later progression to the brain. T. gondii was not detected in any of the organs during the 10-day compound 1 treatment phase, but parasites rebounded immediately after cessation of treatment, suggesting that the compound was not curative. During this recrudescent phase, parasite loads were highest in the brain and undetectable in the peritoneum. The failure of compound 1 to completely clear the parasites in acute toxoplasmosis could be related to its cytostatic nature or perhaps could be due to pharmacokinetic factors; i.e., effective concentrations are not achieved in the relevant mouse tissues. There was no evidence of clinical symptoms despite the parasitological recrudescence (especially in the lung, brain, and spleen) in all mice after cessation of compound 1 treatment. The presence of relatively high parasite loads in mouse tissues with no clinical signs after cessation of compound 1 treatment suggests the involvement of the immune system in controlling T. gondii in these animals. Previous studies with a pyrimethamine-sulfadiazine combination (19) showed the presence of parasites in mouse tissues after cessation of treatment, and this was related to the timing of initial treatment. In those studies, early treatment after infection was curative and parasites were not detected in any of the tissues, while delayed treatment produced relapses after cessation of treatment. Such relapses were attributed to a failure of the drugs to reach critical concentrations in certain organs, which allowed parasites to replicate and spread to additional areas prior to initiation of treatment. In other studies, the efficacy of pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine was limited to the period of administration, and relapse involving the lung and brain was observed soon after cessation of drug treatment (4, 19). However, in our study, infected mice were able to control posttreatment parasitological recrudescence, suggesting a potential synergy between treatment with compound 1 and the immune system.

Pharmacokinetics of compound 1 in the mouse.

Single daily dosing with compound 1 failed to control acute murine toxoplasmosis, suggesting the lack of sustained plasma drug concentrations required to arrest parasite growth in the tissues. A bioassay using recombinant Toxoplasma cGMP-dependent protein kinase demonstrates that the concentration of compound 1 in plasma drops below 100 ng/ml within 8 h of dosing. Compound 1 is required at concentrations of greater than 100 ng/ml (300 nM) to effectively arrest the growth of T. gondii in cultured fibroblasts. Although bioassay measurements will not distinguish between compound 1 and any potential metabolites, only forms of the compound that inhibit the target enzyme are detected, thus providing a measure of levels of active compound in the plasma. To overcome the limitations of compound 1 pharmacokinetics, administration twice daily was required to control T. gondii infections. An alternative strategy would be to develop analogs of compound 1 with greater potency and/or improved pharmacokinetic profiles in order to achieve once-daily dosing.

Role of the immune system in the efficacy of compound 1.

The ability of mice to control recrudescence of toxoplasmosis following compound 1 treatment in our study suggested involvement of the immune system. Experiments in which mice that had been previously cured with compound 1 were protected from a subsequent Toxoplasma infection confirmed that suppression of parasite proliferation with treatment permits active development of an effective long-term immune response. Although parasite titers were undetectable during the treatment period, there were presumably sufficient numbers of parasites present at this time to adequately prime the immune system for the successful resolution of parasite recrudescence (upon withdrawal of therapy) and for the effective control of a subsequent secondary parasite infection upon rechallenge. Interestingly, we observed that compound 1-cured mice are better protected from a subsequent parasite infection than untreated mice exposed to an even higher dose of the relatively avirulent P strain of T. gondii.

We used GKO mice to further investigate role of the immune system in the antiparasitic efficacy of compound 1. The kinetics of T. gondii infection, progression of clinical signs, and ultimate mortality patterns were similar in susceptible wild-type and GKO mice, suggesting that IFN-γ does not influence the outcome of a primary infection with a virulent strain of Toxoplasma. However, in the posttreatment phase, IFN-γ is required for the prevention of mortality associated with recrudescence. The cytostatic nature of compound 1 on T. gondii could provide an opportunity for the development of an IFN-γ-dependent immunity during the 10-day treatment period when parasite replication is limited. It is well established that the control of both acute and chronic T. gondii infection is dependent upon IFN-γ and that the major sources of this cytokine are NK and T cells (7, 21, 22). A role of the immune system in chemotherapy of toxoplasmosis has also been suggested for sulfadiazine (17), one of the major drugs that are currently used for the treatment of human toxoplasmosis.

In summary, we have demonstrated the efficacy of a new chemical entity, compound 1, against toxoplasmosis in the mouse model of acute infection. Compound 1 is an inhibitor of protozoan cGMP-dependent protein kinase, and its efficacy against T. gondii is dependent upon a functional immune system. The effectiveness of this new class of compounds against toxoplasmosis may provide an alternative component for use in combination therapy with other drugs (3, 11) or potentially as a monotherapeutic regimen.

Acknowledgments

B.N. and R.G.K.D. contributed equally to this work

We thank Tesfaye Biftu for supplying compound 1; Ken Bartizal, Maryann Powles, and Dennis Schmatz for help with experimental design and sampling; Jean-François Dubremetz for antibodies; Christopher Hunter and Louis Weiss for advice on the murine toxoplasmosis model; and Kirby Pasloske for assistance with the calculations of pharmacokinetic parameters. We are grateful to Bill Pikounis for performing statistical analyses on all of the animal survival data. We also thank Dennis Schmatz, Wesley Shoop, and Cameron Douglas for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammassari, A., R. Muri, A. Cingolani, A. De Luca, and A. Antinori. 1996. AIDS-associated cerebral toxoplasmosis: an update on diagnosis and treatment. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 219:209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaman, M. H., R. E. MaCabe, S.-Y. BOTTOM-BORDERnd J. S. Remington. 1995. Toxoplasma gondii, p.2455–2487. In R. G. Mandell, R. R. G. Douglas, and J. E. Bennett (ed.), Principles and practice of infectious diseases, 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 3.Dannemann, B. J., J. A. McCutchan, D. Israelski, D. Antoniskis, C. Leport, B. Luft, J. Nussbaum, N. Clumeck, P. Morlat, J. Chiu, J.-L. Vilde, M. Orellana, D. Feigal, A. Bartok, P. Heseltine, J. Leedom, J. S. Remington, and the California Collaborative Team. 1992. Treatment of toxoplasmic encephalitis in patients with AIDS. A randomized trial comparing pyrimethamine plus clindamycin to pyrimethamine plus sulfadiazine. Ann. Intern. Med. 116:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derouin, F., R. Almadany, F. Chau, B. Rouveix, and J. J. Pocidalo. 1992. Synergistic activity of azithromycin and pyrimethamine or sulfadiazine in acute experimental toxoplasmosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:997–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fung, H. B., and H. L. Kirschchenbaum. 1996. Treatment regimens for patients with toxoplasmic encephalitis. Clin. Ther. 18:1037–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furrer, H., M. Egger, M. Opravil, E. Bernasconi, B. Hirschel, M. Battegay, A. Telenti, P. L. Vervazza, M. Rickenbach, M. Flepp, and R. Malinverni, for the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. 1999. Discontinuation of primary prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in HIV-1-Infected adults treated with combination antiretroviral therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 340:1301–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazzinelli, R. T., E. Y. Denkers, and A. Sher. 1993. Host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii: model for studying the selective induction of cell-mediated immunity by intracellular parasites. Infect. Agents Dis. 2:139–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haverkos, H. W. 1987. Assessment of therapy for Toxoplasma encephalitis. The TE study group. Am. J. Med. 82:907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Isrealski, D. M., and J. S. Remington. 1993. Toxoplasmosis in patients with cancer. Clin. Infect. Dis. 17:423–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knoll, L., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1998. Isolation of developmentally regulated genes from Toxoplasma gondii by gene trap with the positive and negative selectable marker HXGPRT. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:807–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kovacs, J. A., and the NIAD-Clinical Center Intramural AIDS Program. 1992. Efficacy of atovaquone in treatment of toxoplasmosis in patients with AIDS. Lancet 340:637–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levy, R. M., D. E. Bredesen, and M. L. Rosenblum. 1995. Neurological manifestations of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): experience at UCSF and review of literature. J. Neurosurg. 62:475–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luft, B. J., and J. S. Remington. 1988. AIDS commentary: toxoplasmic encephalitis. J. Infect. Dis. 157:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luft, B. J., R. Hafner, A. H. Korzun, C. Leport, D. Antoniskis, E. M. Bosler, D. D. Bourland, R. Uttamchandani, J. Fuhrer, J. Jacobson, and members of the ACTG 077p/ANRS 009 Study Team. 1993. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 329:995–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luft, B. J., and J. S. Remington. 1992. Toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.MacFadden, D. C., F. Seeber, and J. C. Boothroyd. 1997. Use of Toxoplasma gondii expressing β-galactosidase for colorimetric assessment of drug activity in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1849–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray, H. W., R. Teitelbaum, and J. Harisprashad. 1992. Response to treatment for intracellular infection in a T cell-deficient host: toxoplasmosis in nude mice. J. infect. Dis. 167:1173–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfefferkorn, E. R., and L. C. Pfefferkorn. 1977. Specific labeling of intracellular Toxoplasma gondii with uracil. J. Protozool. 24:449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piketty, C., F. Derouin, B. Rouveix, and J.-J. Pocidalo. 1990. In vivo assessment of antimicrobial agents against Toxoplasma gondii by quantification of parasites in the blood, lungs, and brain of infected mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1467–1472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roos, D. S., R. G. K. Donald, N. S. Morrissette, and L. C. Moulton. 1994. Molecular tools for genetic dissection of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Methods Cell Biol. 45:27–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scharton-Kersten, T., E. Y. Denkers, R. Gazzinelli, and A. Sher. 1996. Role of IL-12 in induction of cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Res. Immunol. 147:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scharton-Kersten, T. M., W. T. Denkers, E. Y. Bala, E. Grunvald, S. Hieny, R. T. Gazzinelli, and A. Sher. 1996. In the absence of endogenous IFN-gamma, mice develop unimpaired IL-12 responses to Toxoplasma gondii while failing to control acute infection. J. Immunol. 157:4045–4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeber, F. C., and J. C. Boothroyd. 1996. Escherichia coli beta-galactosidase as an in vitro and in vivo reporter enzyme and stable transfection marker in the intracellular protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Gene 169:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soete, M., D. Camus, and J.-F. Dubremetz. 1994. Experimental induction of bradyzoite-specific antigen expression and cyst formation by the RH strain of Toxoplasma gondii in vitro. Exp. Parasitol. 78:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki, Y., M. A. Orellana, R. D. Schreiber, and J. S. Remington. 1988. Interferon-γ: the major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science 240:516–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tagawa, Y., K. Sekikawa, and Y. Iwakura. 1997. Suppression of concanavalin A-induced 1 hepatitis in IFN-g −/− mice, but not in TNF-a −/− mice. J. Immunol. 159:1418–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ware, P. L., and L. H. Kasper. 1987. Strain-specific antigens of Toxoplasma gondii. Infect.Immun. 55:778–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]