Abstract

Expression patterns of gene products provide important insights into gene function. Reporter constructs are frequently used to analyze gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans, but the sequence context of a given gene is inevitably altered in such constructs. As a result, these transgenes may lack regulatory elements required for proper gene expression. We developed Gene Catchr, a novel method of generating reporter constructs that exploits yeast homologous recombination (YHR) to subclone and tag worm genes while preserving their local sequence context. YHR facilitates the cloning of large genomic regions, allowing the isolation of regulatory sequences in promoters, introns, untranslated regions and flanking DNA. The endogenous regulatory context of a given gene is thus preserved, producing expression patterns that are as accurate as possible. Gene Catchr is flexible: any tag can be inserted at any position without introducing extra sequence. Each step is simple and can be adapted to process multiple genes in parallel. We show that expression patterns derived from Gene Catchr transgenes are consistent with previous reports and also describe novel expression data. Mutant rescue assays demonstrate that Gene Catchr-generated transgenes are functional. Our results validate the use of Gene Catchr as a valuable tool to study spatiotemporal gene expression.

INTRODUCTION

The availability of genome sequence data for an ever increasing number of metazoans provides an invaluable tool for understanding gene function. Characterization of the individual genes, however, represents an enormous challenge. In order to rapidly analyze genes, biological investigations are increasingly being performed on a genome-wide scale using high-throughput techniques. Owing to the scope of these projects, it is not always possible to achieve the sensitivity and resolution obtained from studies of single genes. The challenge, thus, is to combine the benefits of traditional ‘gene-by-gene’ approaches with the efficiency and scalability of techniques that can be used for genome-wide studies.

Gene expression patterns provide information regarding the developmental timing and spatial location of gene activity, which contribute to the understanding of gene function. Caenorhabditis elegans represents an ideal model system in which to study gene expression patterns. It is transparent, facilitating live imaging of gene expression throughout development. The complete cell lineage has been described and is essentially invariant from animal to animal (1–3), allowing unequivocal identification of cells in which specific genes are being expressed. The C.elegans genome is relatively small, yet it contains a surprisingly large number of genes (∼20 000), of which nearly 40% show homology to those of other multicellular animals (4).

Antibody staining provides the most accurate and sensitive in vivo protein localization data, but the time and cost involved in generating antibodies for each C.elegans protein preclude its application to the study of many proteins in parallel. In attempting an analysis of gene expression, it would be ideal to modify endogenous genes in their genomic context. Insertion of reporters into the genome has been used to study expression patterns in several organisms, notably in yeast (5) and Drosophila (6,7) (http://flytrap.med.yale.edu). Homologous gene targeting is not yet routinely successful in C.elegans and has to date been used to insert a GFP reporter at only one locus (8).

Several large-scale techniques are currently being employed to generate a more comprehensive C.elegans expression pattern map, including RNA in situ hybridization (http://nematode.lab.nig.ac.jp) and production of reporter-fusions (9–14) (http://bgypc059.leeds.ac.uk/~web; http://elegans.bcgsc.ca). While these methods are extremely powerful, they have certain limitations. In situ hybridization patterns in C.elegans provide low resolution information about RNA accumulation, and may differ from patterns of protein expression. Reporter-fusion constructs represent important analytical tools, but many contain only short fragments of 5′ flanking sequence from the gene of interest and may lack more distal upstream regulatory elements as well as any within introns, 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) and 3′ flanking sequence, which are important for gene expression and protein localization in C.elegans (15–17) and in other animals (18–20). It would be ideal to include the complete open reading frame (ORF) and all relevant regulatory elements associated with a gene of interest when generating reporter transgenes. To this end, we have developed Gene Catchr: Gene Cloning And Tagging for C.elegans using yeast Homologous Recombination, a novel method for generating functional translational GFP fusions of worm genes that exploits YHR. This system confers several useful features. It avoids the use of long-range PCR and attendant risk of mutagenesis, and is not constrained by the existence of convenient restriction sites. YHR facilitates the cloning and tagging of entire loci within arbitrarily large genomic regions; it thus maximizes the possibility that a reporter construct will capture all regulatory elements associated with a given endogenous gene and faithfully mimic its expression pattern. Gene Catchr is highly flexible in that any fluorescent reporter and/or epitope tag can be inserted at any desired site without introducing extraneous marker sequences that may interfere with protein expression or localization. Finally, the system requires only yeast transformation, PCR and plating on selective media. Each step is simple and can be adapted to process multiple genes in parallel.

Using Gene Catchr, we have reproduced expression patterns for a number of C.elegans gene products, demonstrating the accuracy of our system, and also describe novel expression data. We have established that our transgenes are functional by rescuing several mutant phenotypes. Gene Catchr represents a valuable tool for gene expression studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains

Yeast strains used in this study were the YAC host strain, AB1380 (MATa ade2–1 can1-100 lys2-1 trp1-289 ura3-52 his5 [ψ+]) (21) and the cytoduction recipient strain, ASHSY2 (MATα leu2-3,112 ura3-52 his5Δ::kanMX6 cyh2 kar1-1). ASHSY2 was derived from CBY668 (MATα ade2-101 leu2-3,112 ura3-52 cyh2 kar1-1) (22) by restoring a wild-type copy of ADE2 and by deleting HIS5 using standard PCR-based methods (23).

Worm strains and nomenclature

We used the standard wild-type strain of C.elegans var. Bristol, N2. All strains and alleles used in this study are derivatives of N2 and can be found in WormBase (http://www.wormbase.org) and references therein. Strains and alleles used in this study are: CB190 unc-54(e190) I, CB3591 tra-2(e1095)/mnC1 II, GE1076 pha-1(e2123) III; lon-2(e678) X and MT5475 aex-3(n2166) X. We denote full-length translational fusions as gfp::gen-1 for N-terminal fusions and gen-1::gfp for C-terminal fusions where gen-1 represents the gene in question. (For examples see Figure 1.)

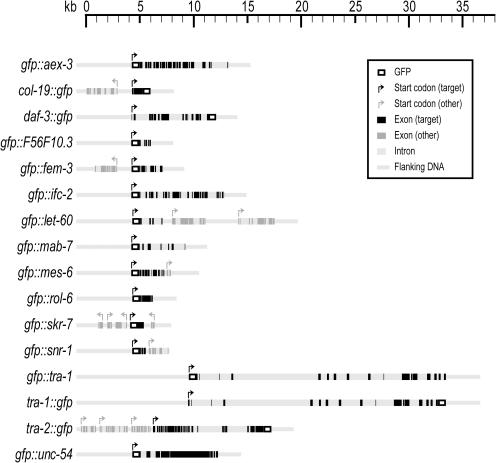

Figure 1.

Genomic architecture of representative genes targeted by Gene Catchr. All cloned regions contain ∼5 kb upstream and 2 kb downstream of the ORF of the gene of interest, with the exception of tra-1 which contains ∼10 kb of upstream and 3 kb of downstream sequence. Scale bar units are in kilobases. Gene orientation is indicated by the direction of the start codon arrow. Additional cloned genes are represented as lighter boxes.

Worm transformation

C.elegans was cultured and manipulated as described previously (24) on MYOB agar (25). To generate expression lines Gene Catchr constructs were microinjected (26) into N2, except for gfp::rol-6, which was microinjected into GE1076 (27,28). All injection mixtures contained 3–100 µg/ml of Gene Catchr construct. Injection mixtures for N2 worms contained 50 or 100 µg/ml of the transformation marker plasmid pRF4 (26). Injection mixtures for GE1076 worms contained 50 µg/ml of the transformation marker plasmid pC1 (27).

For mutant rescue experiments, gfp::unc-54 DNA was injected at 50 µg/ml, tra-2::gfp was injected at 50 µg/ml along with 50 µg/ml of pRF4, and gfp::aex-3 was injected at 10 µg/ml, along with 40 µg/ml of pRF4. For both expression and mutant rescue assays, at least three independent lines were generated for each transgene. In all cases, the total DNA concentration in the injection mixtures was kept between 100 and 200 µg/ml by adding carrier DNA where necessary. All transgenes were maintained in worms as extrachromosomal arrays.

Plasmid construction

pCatchr1 and pCatchr4 were derived from pCRG29 and pCRG26, respectively (all pCRG vectors are described in http://www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC/protocols/Gapture.cfm). The URA3 marker from pCRG29/26 was replaced with HIS5 using YHR. A HIS5 fragment was amplified from yeast genomic DNA using primers HIS5 up BsiWI 17.F and HIS5 down BsiWI 2064.R and inserted into a BstBI-linearized YCplac33 derivative (29) using YHR. Primers HIS5 CRG.F and HIS5 CRG.R were used to amplify the cloned HIS5 fragment, which was then inserted into NsiI-linearized pCRG29 or 26 by YHR. In addition, the CYH2 marker of pCRG26 was replaced with URA3. The URA3 insert was amplified from pJJ242 (30) using primers URA CRG.F and URA CRG.R and inserted into SphI-linearized pCRG26 by YHR, producing pCatchr4. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1S.

pCatchr2 is a derivative of pCRG13, but contains the URA3 marker in place of the CYH2 marker.

pCatchr3: A XhoI–EcoRI fragment containing part of the GFP coding sequence, was subcloned from pPD95.67 (http://www.ciwemb.edu/pages/firelab.html). A SmaI–SalI fragment containing the URA3 marker was subcloned from pJJ242. These fragments were cloned simultaneously into BstZ17I–EcoRI cut pPD95.67, generating pCatchr3.

Cloning linker and targeted-tag synthesis

All primers were obtained either from Invitrogen or Tim Hughes' laboratory at the University of Toronto. For both standard and alternative methods, cloning linkers were synthesized using Taq DNA Polymerase and worm genomic DNA as a template. Primers for the standard cloning method are listed in Supplementary Table 2S, and for the alternative cloning method in Supplementary Table 3S. Amplification conditions were as follows: 94°C for 5 min; 3 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; 21 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min; 24 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 7 min. Linkers were passed through Montage PCR columns (Millipore). For tagging, targeted-tags were generated by PCR amplification of the GF-URA3-FP cassette from pCatchr3 using TaKaRa Ex Taq (TAKARA BIO Inc.) as described by the manufacturer. Targeted-tag primers are listed in Supplementary Table 4S. Amplification conditions were as follows: 3 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min, 30 s; 27 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, 72°C for 2 min, 30 s, followed by 72°C for 7 min. In all cases, concentrations of the PCR fragments were estimated from 1 to 2% agarose gels.

Yeast transformation and selective plating

Yeast transformation reactions were performed essentially as described (http://www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/medicine/biochem/gietz).

For standard cloning, the following components were used to transform yeast bearing the appropriate YAC strain: 100 ng of SrfI (Stratagene)-linearized pCatchr1/4, 1 µg of upstream linker and 1 µg of downstream linker. Transformation reactions were plated on SC-HIS, and positive clones were then patched onto SC-HIS plus 5-Fluoro-orotic acid (1 mg/ml 5-FOA; Bioshop Canada Inc.), permitting the growth of only those yeast cells that contained the correct plasmid, but had lost the YAC during cell division. For tagging, 0.5–1.5 µg of the targeted-tag was used to transform yeast bearing the pCatchr1/4 target clone. Transformation reactions were plated on SC-HIS-URA.

For the alternative cloning method, the following components were used to transform the AB1380 yeast strain: 100 ng of SrfI-linearized pCatchr1, 400 ng of HpaI-linearized pCatchr2, 1 µg of upstream linker and 1 µg of downstream linker. Transformation reactions were plated on SC-HIS-URA. Constructs (targeting vectors) were isolated by yeast plasmid rescue, amplified in bacteria (see Yeast plasmid rescue section below) and linearized with SrfI. In a second yeast transformation reaction, the yeast bearing the appropriate YAC strain was transformed with 100 ng of SrfI-linearized targeting vector. Transformation reactions were plated on SC-HIS, and positive clones were then patched onto SC-HIS plus 5-FOA as described above for the standard cloning method.

Selection of exceptional cytoductants and assembly of GFP tag

Positive transformants containing both GF-URA3-FP tagged and untagged target regions in pCatchr1/4 in the AB1380 genetic background (the donor strains) were patched on to SC-HIS-URA and incubated at 30°C for 2 days. ASHSY2 (the kar1-1 recipient strain) was grown up as a lawn at 30°C on solid YPD medium. ASHSY2 lawns were replica-plated onto fresh solid YPD medium. The donor strains were then replica-plated on top of the ASHSY2 lawns. The strains were mated at 30°C overnight. To facilitate the isolation of GF-URA3-FP containing plasmids in the ASHSY2 background, a series of selective plating steps was carried out. The mated yeast strains were replica-plated onto SC-HIS plus 3 µg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma–Aldrich, Inc.) and incubated at 30°C for 6 days. White colored papillae were streaked onto SC-HIS plus 3 µg/ml cycloheximide plates. The resulting single white colonies were then streaked onto SC-HIS-URA and subsequently streaked onto YPD or SC-HIS media. To select yeast in which YHR resulted in the excision of the intervening URA3 marker from the isolated GF-URA3-FP tagged plasmids, plasmid cytoductants were patched onto SC-HIS plus 5-FOA.

Diagnostic PCR assays

Yeast transformants containing the target gene, the target gene with the GF-URA3-FP tag or the target gene with the reconstituted GFP tag were detected by whole-cell diagnostic PCR after 5–7 days. PCR assays were performed in 96-well format, first in pools of 3–4 colonies, followed by identification of single positives, using Taq DNA Polymerase. Diagnostic primers are listed in Supplementary Table 5S–8S. Amplification conditions were as follows: 94°C for 8 min, 30–45 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 58°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, followed by 72°C for 7 min. Sizes of PCR products were determined from 1 to 2% agarose gels.

Yeast plasmid rescue

Plasmid DNA was prepared from yeast by either of two methods: (i) cell wall lysis in zymolyase (ICN) (http://www.chin-sang.ca) followed by standard miniprep (Qiagen, Inc.) or (ii) phenol:chloroform extraction coupled with glass beads (0.5 mm, BioSpec Products, Inc.) as described previously (31) with minor modifications: after vortexing the yeast cells in the presence of lysis buffer and glass beads, 200 µl of TE, pH 8.0, was added, the samples were spun for 5 min and the aqueous phase collected. NaOAc (3M) (30 µl) and 1 ml of 100% ethanol were added to the aqueous phase, the samples were spun for 10 min, and the supernatant removed. The pellet was washed twice with 70% ethanol, dried and resuspended in 50 µl of dH2O. Electrocompetent Escherichia coli DH10B™ was transformed with 1–3 µl of DNA, and plated on Luria–Bertani containing 6.8 µg/ml chloramphenicol (Sigma–Aldrich, Inc.). Low-copy plasmid DNA from individual colonies was isolated by midiprep (Qiagen, Inc.) and analyzed by restriction digest.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA). Detailed protocols and reagents are available upon request.

RESULTS

Overview of the Gene Catchr method

The Gene Catchr method was developed using a set of genes with various characteristics that would enable us to test the capabilities of the system. Our target genes span a size-range representative of worm genes, some of which reside in operons (Figure 1 and Table 1). We included well-characterized genes to test the ability of our transgenes to generate accurate protein localization patterns. We also chose genes that have corresponding mutant alleles in order to determine if our transgenes are functional in genetic assays.

Table 1.

Summary of genes cloned by Gene CATCHR: gene function, structure and size of target region, and cloning efficiency

| Gene | Function | Operon | Other genes targeteda | Target size (kb) | Efficiencyb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aex-3 | Guanine nucleotide exchange factor; regulates defecation and male mating | 15.2 | 3/32c | ||

| bar-1d | Beta-catenin/armadillo homolog; affects vulval specification and cell migration | 11.7 | 3/48 | ||

| C02H7.1 | Uncharacterized | T04G9.5; T04G9.3; (T04G9.7) | 14.3 | 4/16c | |

| che-2 | Affects chemotaxis, dauer formation, and longevity | 12.1 | 1/16 | ||

| col-19 | Member of the collagen superfamily | ZK1193.3 | 10.0 | 1/16 | |

| daf-3 | Encodes a Smad protein; required for formation of the dauer larval stage | 14.2 | 2/48 | ||

| dom-6e,f | Cell cycle control protein homolog | CEOP4294 | mes-6 | 10.7 | 2/9 |

| F13C5.1 | Uncharacterized | F13C5.4; F13C5.5 | 17.1 | 1/16 | |

| F13C5.2 | Uncharacterized | F13C5.3; F13C5.4 | 14.2 | 2/16 | |

| F28C10.2 | Uncharacterized | F28C10.4; F28C10.1 | 11.0 | 4/32c | |

| F39H12.4 | Uncharacterized | 12.7 | 1/16 | ||

| F56F10.1 | Uncharacterized | 10.8 | 2/16 | ||

| F56F10.3 | Uncharacterized | 8.3 | 1/16 | ||

| F56F10.4 | Uncharacterized | (F56F10.1) | 13.0 | 2/64 | |

| fem-3f | Promotes male development | C01F6.3 | 9.5 | 7/104 | |

| gei-10 | GEX Interacting protein | 16.8 | 1/32 | ||

| hsp-16.2f | Heat shock protein | (hsp-16.41; Y46H3A.1) | 7.5 | 1/111 | |

| ifc-2 | Intermediate filament protein required for movement and growth | 15.0 | 1/9 | ||

| irk-2 | Inwardly rectifying potassium channel | M02A10.1 | 13.3 | 2/16 | |

| let-60f | RAS proto-oncogene family member required for viability and vulval induction | CEOP4472 | ZK792.5; ZK792.4 | 19.7 | 1/64 |

| let-756 | FGF-like ligand | (C05D11.5) | 10.1 | 2/19 | |

| mab-7 | Required for male ray morphogenesis | 11.3 | 2/32 | ||

| mes-6e,f | Required for germline development | CEOP4294 | dom-6 | 10.7 | 2/9 |

| mrp-1g | Uncharacterized | CEOPX154 | 18.2 | 1/16 | |

| nas-38 | Nematode AStacin protease | hlh-19 | 12.6 | 3/16 | |

| ppp-1e,f | PyroPhosPhorylase family member | CEOP2268 | tra-2; (C15F1.6; C15F1.5) | 19.3 | 3/102 |

| pqn-40 | Prion-like-(Q/N-rich)-domain-bearing protein | 14.0 | 1/63 | ||

| rol-6f | Cuticle collagen | 8.4 | 1/24 | ||

| skr-7f | Homolog of yeast Skp1 | Y47D7A.7; (skr-14; Y47D7A.2; Y47D7A.9) | 8.1 | 1/14 | |

| sli-1 | Homolog of the proto-oncogene c-Cbl | 12.3 | 1/16 | ||

| snr-1d | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein SmD3 | (Y116A8C.43) | 7.8 | 3/48 | |

| T04G9.1 | Uncharacterized | 14.0 | 1/44 | ||

| T19D7.3 | Uncharacterized | T19D7.2; T19D7.4; (T19D7.5) | 15.9 | 2/16 | |

| tra-1d | Homolog of human GLI3; required for female fate specification | 36.4 | 1/32 | ||

| tra-2e,f | Transmembrane receptor; required for female fate specification | CEOP2268 | ppp-1; (C15F1.6; C15F1.5) | 19.3 | 3/102 |

| unc-54f | Muscle myosin class II heavy chain; required for locomotion and egg-laying | 14.9 | 2/14 | ||

| Y87G2A.10d | Uncharacterized | CEOP1708 | Y87G2A.11; Y87G2A.12; (Y87G2A.13) | 19.0 | 10/24 |

aBracketed genes are contained as complete ORFs, but may be flanked by <5 kb of upstream sequence and/or <2 kb of downstream sequence.

bEfficiency = (number of positive colonies)/(total number of colonies tested). 9–111 colonies tested (mean = 37).

cSome numbers in the efficiency column may reflect an under representation, as a positive pool was counted as a single positive, but may contain more than one positive clone.

dThese genes were cloned by the alternative cloning method (see Figure 4).

edom-6 and mes-6 reside in the same operon, and therefore do not represent distinct clones. The same is true for ppp-1 and tra-2.

fThese genes were cloned into pCATCHR4; all others were cloned into pCatchr1.

gmrp-1 is the most upstream gene in operon CEOPX154. The downstream gene in the operon, mrp-2, was not subcloned.

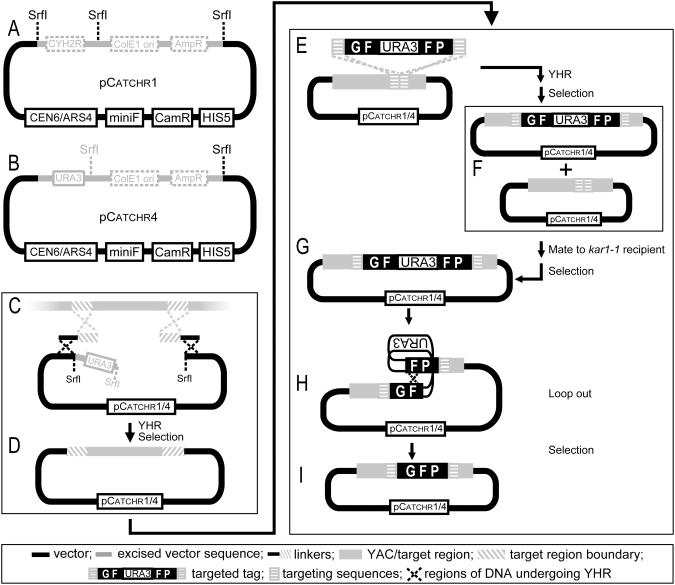

Gene Catchr involves several simple steps which are described in more detail below. The method is straightforward, and involves only yeast transformation, PCR, selective plating and plasmid purification. The first few steps are performed in a yeast host in order to exploit YHR. First, the target gene is subcloned from a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) into a shuttle vector in one yeast transformation reaction. In a second yeast transformation reaction, the cloned gene is tagged with a gfp cassette containing a selectable marker. The marker is subsequently excised by plating the yeast on the appropriate selective media. The plasmid containing the tagged-target gene is then recovered from yeast, amplified in bacteria and purified. As is routinely done in C.elegans, constructs are introduced into worms by microinjection.

Cloning

Our objective was to clone each worm gene along with all of its associated regulatory elements. The gene density in C.elegans is approximately one gene per 5 kb (4) and regulatory regions generally reside within 4 kb of DNA upstream of a start codon (15), and may reside within introns and 3′-UTRs. Therefore, for each gene of interest, we decided to target genomic regions, referred to as ‘target regions’, which extend from ∼5 kb upstream of the start codon to 2 kb downstream of the stop codon (Figure 1 and Table 1). If a gene was part of an operon, the entire operon was targeted.

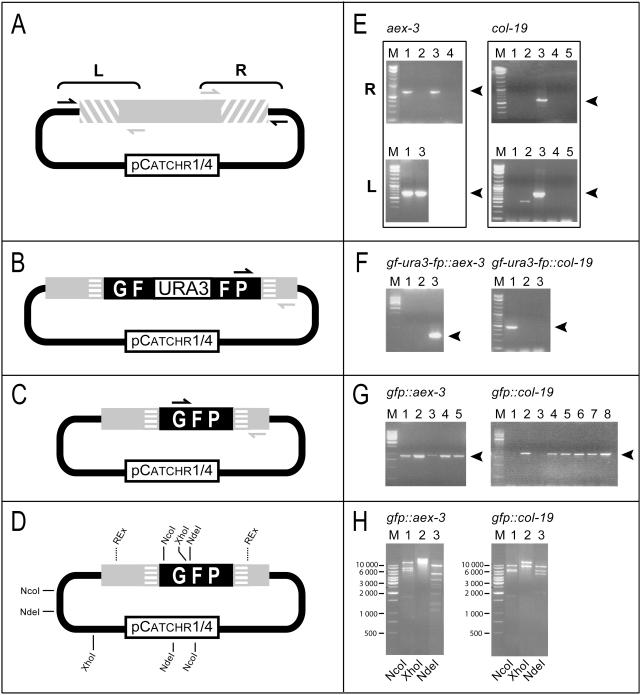

To clone target regions, we used a variation of linker-mediated gap repair in yeast (32,33) and exploited a YAC collection representing 98% of the C.elegans genome. A target region is subcloned into a linearized shuttle vector, pCatchr1 or pCatchr4 (Figure 2A and B), in one yeast transformation step (Figure 2C and D). For each target region, the yeast strain bearing a YAC containing the desired target is transformed simultaneously with three pieces of DNA: the shuttle vector (linearized pCatchr1/4), plus upstream and downstream linkers (PCR products containing homology to both the shuttle vector and the target region boundaries). Colonies arising from each transformation reaction are tested directly by a whole-cell diagnostic PCR assay (Figure 3A and E). Positive clones are then patched onto selective media to permit the growth of only those yeast cells that contain the correct plasmid, but have lost the YAC during cell division. This step is necessary, as the presence of a YAC, which contains a URA3 marker, would interfere with the subsequent tagging step.

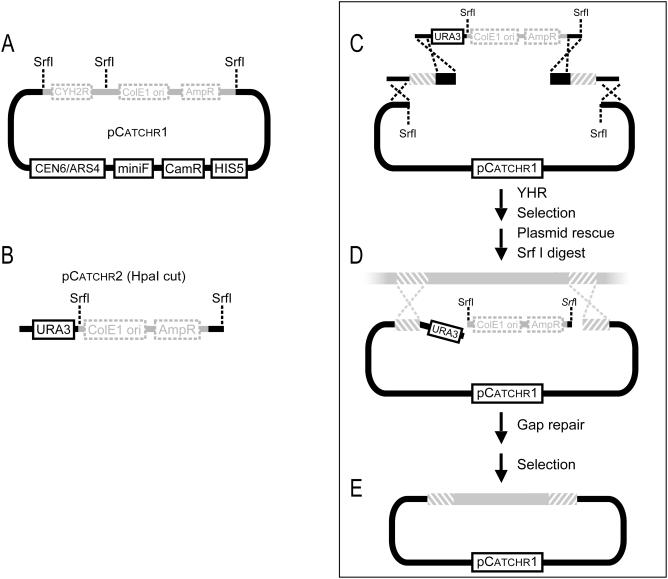

Figure 2.

Overview of the Gene Catchr method. (A–D) Cloning steps; (E–I) tagging steps. Schematic representations of the shuttle vectors (A) pCatchr1 and (B) pCatchr4. pCatchr1/4 has two origins of replication for E.coli: miniF for low-copy plasmid maintenance, and ColE1 for high-copy plasmid maintenance. The ColE1 origin allows for efficient amplification of pCatchr1/4, but is removed by SrfI digestion once a large insert is subcloned, to prevent rearrangements often associated with large high-copy plasmids (33,63,64). Linearization of pCatchr1/4 with SrfI produces a vector with free ends, and a URA3 overhanging fragment in the case of pCatchr4 only [(C) shown in gray]. Subsequent selection against the URA3 marker ensures that pCatchr4 plasmids incorrectly formed by recircularization are eliminated. (C) Linkers contain 450–700 bp of homology to the target region boundaries and 40 bp of homology to the free vector ends. Yeast containing the appropriate YAC are transformed with SrfI-linearized pCatchr1/4 and linkers. (D) Correct plasmids are formed by YHR, and contain the target region cloned into pCatchr1/4. (E–I) Summary of the Gene Catchr tagging method. (E) The GF-URA3-FP targeted-tag contains the GFP coding sequence with 288 bp direct repeats (‘F’) encoding parts of gfp exons 2 and 3, interrupted by the URA3 marker, and flanked by targeting sequences (40–50 bp) homologous to the insertion site in the cloned gene. (E and F) GF-URA3-FP is inserted into the cloned worm gene in pCatchr1/4 by YHR. (F) After selection, vectors containing both tagged and untagged genes are present in the resulting yeast colonies. (F and G) Exceptional cytoduction (mating to a kar1-1 recipient strain and subsequent selection steps) is used to isolate yeast cells containing only the tagged plasmids. (H and I) Direct repeats (‘F’) in the gfp sequence allow for the excision of the URA3 marker, thereby reconstituting the GFP tag.

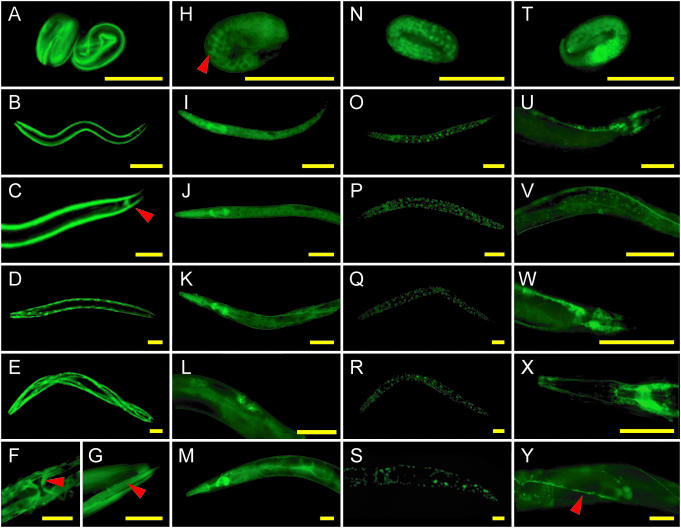

Figure 3.

Sample whole-cell diagnostic PCR assays and restriction digests. Examples are shown for aex-3 and col-19. Arrowheads indicate expected PCR products. (A and E) Diagnostic PCR assays to identify correctly cloned target regions in pCatchr1/4. Only clones that are positive for both the left (L) and right (R) junctions are correct (i.e. aex-3 clones 1 and 3; col-19 clone 3). (B and F) Diagnostic PCR assays to identify clones containing the GF-URA3-FP tag (correct clones: gf-ura3-fp::aex-3 clone 3; gf-ura3-fp::col-19 clone 1). (C and G) Diagnostic PCR assays to identify clones containing a reconstituted GFP tag (correct clones: gfp::aex-3 clones 1–5; gfp::col-19 clones 2, 4–8). (D and H) Restriction digests of plasmid DNA to confirm the final construct. The restriction enzymes NcoI, XhoI and NdeI cut within the GFP tag and the vector, and tend to cut within the target region (REx represents gene-specific recognition sites), and allow us to differentiate between clones that contain an interrupted GFP tag, a reconstituted GFP tag or no tag.

The largest fragment that we cloned using this method was 28 kb (data not shown). It may be possible to clone larger target regions, as we have not tested the upper limit of the insert size that we can capture. We subcloned 31 out of 35, or 89%, of target regions (Table 1), indicating that the cloning step is efficient for capturing large genomic regions. The remaining four genes were cloned by an alternative cloning method (see below).

Tagging

Tagging of genes cloned into pCatchr1/4 is performed in three simple steps (Figure 2E–I): (i) introduction of an interrupted targeted-tag (GF-URA3-FP), (ii) isolation of the desired tagged plasmid from a heterogeneous plasmid population and (iii) formation of an uninterrupted tag. In the first step, a yeast strain containing the worm gene of interest cloned in pCatchr1/4 is transformed with GF-URA3-FP (Figure 2E) (22,34). This fragment (Materials and Methods) consists of the GFP coding sequence interrupted by a URA3 marker, and flanked on each end by sequences with homology to the tag integration site in the worm gene. A portion of the GFP coding sequence (denoted ‘F’) is repeated on each side of the URA3 marker. Integration of the tag at the appropriate site is accomplished by YHR, and positive clones are identified by a whole-cell diagnostic PCR assay (Figure 3B and F).

As observed previously by Hawkins et al. (22), we found that in addition to the desired product, positive yeast clones frequently contained untagged constructs which interfered with subsequent recovery of the tagged construct (Figure 2F). To eliminate this problem, a second step was introduced. Individual tagged plasmids from positive transformants (donors) were transferred into a kar1-1 recipient yeast strain by exceptional cytoduction (22), which simply involves a mating step followed by a series of replica-platings. kar1-1 mutants are deficient in nuclear fusion, and exchange of chromosomal DNA between cells during mating is limited. Occasionally, the resulting transient heterokaryons segregate haploid progeny termed exceptional cytoductants which result from the transfer of either a single chromosome or a plasmid from the nucleus of a donor strain to the nucleus of a recipient strain (35,36). We isolated yeast containing only tagged plasmids by selecting for the appropriate exceptional cytoductants: those with the nuclear genotype of the kar1-1 recipient containing tagged plasmids from the donor strain.

The third step is the assembly of an uninterrupted GFP tag (Figure 2H and I). Selection against URA3 allows the isolation of plasmids in which recombination between the flanking ‘F’ repeats leads to the excision of the intervening URA3 sequence (22,34) producing a functional GFP coding sequence. Positive clones containing the assembled GFP tag are identified by a whole-cell diagnostic PCR assay (Figure 3C and G). Tagged plasmids are then isolated from yeast by plasmid rescue, amplified in E.coli, and verified by restriction enzyme analysis (Figure 3D and H).

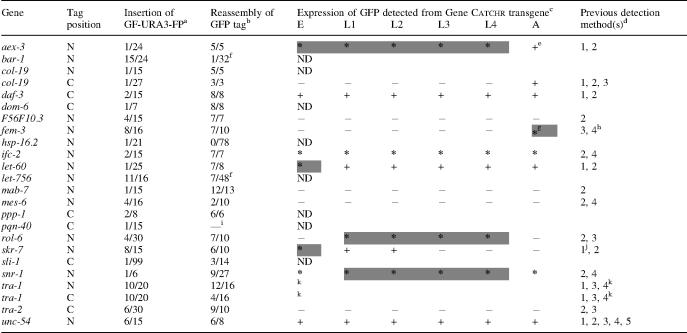

The genes tagged using Gene Catchr are listed in Table 2. Integration of the GF-URA3-FP tag at the desired site was successful in 24 out of 29, or 83%, of our attempts. Reassembly of the functional GFP coding sequence by URA3 loop-out was successful in 22 out of 24, or 92%, of our attempts. Once the final tagged vectors were obtained in yeast, the efficiency of recovering the constructs was 91% (20 out of 22 attempts).

Table 2.

Summary of genes tagged by Gene CATCHR: tagging efficiencies, expression patterns generated and comparisons with previously reported data

a,b(number of positive colonies)/(total number of colonies tested).

a6–99 colonies tested (mean = 21).

b3–78 colonies tested (mean = 15).

cAll expression patterns were examined in hermaphrodites, except where noted. Symbols used to describe GFP expression patterns generated from Gene CATCHR transgenes: E, embryo; L1–L4, larval stages 1 through 4; A, adult; ND, not done; plus, GFP detected; minus, GFP not detected; asterisks, GFP detected, expression from reporter transgene previously unpublished; shaded cells, protein localization data previously unpublished.

dAs described in WormBase (http://www.wormbase.org) and references therein or the Nematode Expression Pattern DataBase (NEXTDB, http://nematode.lab.nig.ac.jp) with additional information as indicated. 1, translational reporter-fusion; 2, RNA in situ hybridization; 3, northern analysis/dot blot; 4, antibody staining; 5, transcriptional reporter-fusion.

eExpression patterns from a translational fusion have been analyzed in adults, but it is unclear what other developmental stages were examined (44).

fConstructs containing a reassembled GFP tag were detected by PCR; however, the constructs were not successfully isolated from yeast.

gExpression examined in males.

hA. Puoti, personal communication.

iAfter cytoduction, no colonies formed on SC-HIS plus 5-FOA plates.

jAlso K. Nakayama, personal communication.

kM. Schvarzstein and A. M. Spence, manuscript in preparation.

A typical timeline for cloning and tagging is as follows: one week for subcloning, one week for tag insertion, three weeks for cytoduction, and one week for the final loop-out and plasmid recovery. Therefore, a standard construct takes ∼6 weeks from beginning to end. It is worth noting that the majority of this time is spent waiting for yeast to grow; only 5–6 days of laboratory benchwork are required.

Alternative cloning method

A small number of genes (bar-1, snr-1, tra-1 and Y87G2A.10) (Table 1) were refractory to the cloning method presented above, and these were cloned by an alternative approach adapted from a previously described recombinational cloning method (http://www.genome.washington.edu/UWGC/protocols/Gapture.cfm) and reviewed in (37). The method involves the generation of a targeting vector, followed by insertion of worm DNA into the targeting vector by gap repair from a YAC (Figure 4). This approach is more laborious than the standard method, as it requires an extra yeast transformation reaction and an extra plasmid rescue step. However, it has a higher probability of success because the final product results from two recombination events, as opposed to the four recombination events required for the standard method.

Figure 4.

Alternative cloning method. Two plasmids are required: (A) pCatchr1 (SrfI-linearized) and (B) pCatchr2 (HpaI-linearized). pCatchr2 serves as a ‘stuffer fragment’ that contains the high-copy ColE1 origin of replication, exploited as described in Figure 2, and a URA3 marker to prevent recircularization of empty vectors. (C) The first cloning step consists of generating a targeting vector. The yeast strain AB1380 is simultaneously transformed with four DNA fragments: SrfI-linearized pCatchr1, HpaI-linearized pCatchr2, and upstream and downstream linkers. Linkers are generated by PCR and contain 450–700 bp of homology to the target region boundaries flanked by 40 bp of sequence homologous to the pCatchr1 and pCatchr2 vector ends. The desired product from this transformation reaction results from four homologous recombination events, and consists of the stuffer fragment, flanked by target region boundaries, inserted in pCatchr1. Transformation reactions are plated on selective media, and resulting plasmids are purified from yeast. (D) The next step involves gap repair of the targeting vector. The targeting vector is linearized with SrfI to release the ColE1 ori cassette, leaving behind free worm DNA ends with a URA3 overhanging fragment on the upstream end. A yeast strain bearing a YAC containing the desired worm target region is transformed with the SrfI-linearized targeting vector. The worm genomic region is gap repaired from the YAC into the targeting vector. (E) Correct plasmids contain the target region cloned into pCatchr1. The remaining diagnostic and selection steps are identical to those described for the standard cloning method. See Figure 2 for legend details.

We successfully cloned all of the genes attempted using the alternative cloning method (Table 1). Notably, a 36 kb fragment containing tra-1, the terminal regulator of sex determination in C.elegans, was subcloned using this method. tra-1 represents one of the larger C.elegans genes (23 kb transcription unit), and it resides in a region of the genome that has proven refractory to conventional cloning methods (38). Our Gene Catchr derived transgene will facilitate further functional analysis of tra-1. Our ability to isolate tra-1 illustrates the general utility of the Gene Catchr system.

Gene expression analysis

To test the accuracy of the expression patterns generated by our system, we used Gene Catchr to produce GFP-tagged translational fusions of genes that have been characterized previously by one or more methods (Table 2). Moreover, we extended our analysis to all stages of worm development and also included genes for which there are no published reports of either protein localization or reporter expression. In cases where GFP was detected, the spatiotemporal expression patterns were in agreement with previous reports and consistent with gene function (Table 2, Figures 5 and 6) (http://www.wormbase.org and references therein; http://nematode.lab.nig.ac.jp), demonstrating the accuracy of the Gene Catchr system.

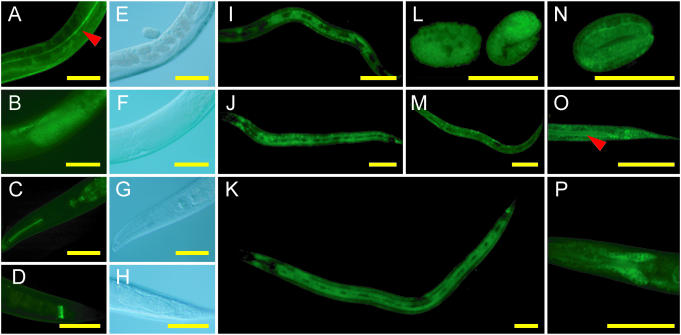

Figure 5.

Fluorescence images of developmental GFP expression patterns of transgenic worms carrying Gene Catchr-derived transgenes. (A–G) GFP::UNC-54; (H–M) GFP::LET-60; (N–S) GFP::SNR-1; (T–Y) GFP::AEX-3. (A, H, N and T) Embryos; (B, I, O and U) L1 larvae; (C, J, P and V) L2 larvae; (D, K, Q and W) L3 larvae; (E, L, R and X) L4 larvae; (F, G, M, S and Y) adults. In all images, anterior is to the left. (K, M and X) anterior region; (F, L, V and Y) midbody region; (C, G, S, U and W) posterior region. Consistent with results obtained by antibody staining and reporter-fusions (16,65,66), we detect GFP::UNC-54 in body wall muscles from late embryogenesis to adulthood (A–G), in vulval muscles as indicated by the red arrowhead in (F), and in the anal depressor as indicated by the red arrowhead in (C). Notably, the GFP::UNC-54 fusion protein accurately localizes to myofilaments of body wall muscles, indicated by the red arrowhead in (G). (H–M) GFP::LET-60 is detected throughout development in many tissues and cell types including the pharynx, intestine, hypodermis, neurons and vulva, in accordance with previous results (67). Note accumulation at the cell periphery in embryos (H) indicated by the red arrowhead. (N–S) Nuclear accumulation of GFP::SNR-1. (T–Y) GFP::AEX-3 expression in neurons. The ventral nerve cord is indicated by the red arrowhead in (Y). Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Figure 6.

Representative expression patterns of transgenic worms carrying Gene Catchr-derived transgenes. (A and E) COL-19::GFP; (B and F) GFP::FEM-3; (C, D, G and H) GFP::IFC-2; (I–K) GFP::ROL-6; (L and M) GFP::SKR-7; (N–P) DAF-3::GFP. (L and N) Embryos; (I, M and O) L1 larvae; (J and P) L2 larvae; (K) L4 larva; (A–H) adults. (E–H) DIC images corresponding to GFP fluorescence images (A–D), respectively. (A and E) COL-19::GFP is detected in the cuticle of adult worms, in agreement with previous results (41,68). Note localization to the lateral alae indicated by the red arrowhead (A). (B and F) GFP::FEM-3 accumulation in sperm in adult males. (C and G) GFP::IFC-2 in the pharynx and (D and H) in the posterior of the intestine. In accordance with results obtained by antibody staining (69), we detect GFP::IFC-2 in pharyngeal and intestinal cells at all stages of development (C, D, G and H and data not shown). This represents the first account of ifc-2 expression from a reporter transgene. (I–K) GFP::ROL-6 expression in the hypodermis, excluding the seam cells. (L and M) GFP::SKR-7 is widely expressed in embryos (L), L1 larvae (M) and L2 larvae (not shown). (N–P) DAF-3::GFP is expressed in several tissues including the tail and lumenal surface of the intestine (indicated by the red arrowhead) (O), and the head neurons (P), consistent with results obtained from a translational fusion construct (70). Scale bars represent 50 µm.

We generated novel protein expression data for several genes including snr-1, rol-6 and fem-3. Barbee et al. (39) previously used a pan-SNR antibody to detect SNR protein accumulation in the nuclei and cytoplasm of embryos and in the adult germline. Our Gene Catchr-derived GFP::SNR-1 fusion extends this result by showing that SNR-1 accumulates in the nuclei of many cell types throughout development (Figure 5N–S). The rol-6 gene encodes a cuticular collagen, and while its mRNA is detectable during each larval stage (40) (http://nematode.lab.nig.ac.jp), a previously described reporter construct was not detectably expressed (41). A Gene Catchr-derived GFP::ROL-6 fusion, in contrast, shows expression in the hypodermis excluding the seam cells, in L1-L4 worms at the time of each molt (Figure 6I–K and data not shown). This represents the first report of ROL-6 protein localization. Finally, the fem-3 gene is required for spermatogenesis and for development of the male soma. Northern analysis demonstrated its expression in the germline (42), but evidence of its expression in situ has not been published. We observed GFP::FEM-3 in the spermatids of both adult males (Figure 6B and F) and hermaphrodites (data not shown). FEM-3 immunofluorescence has yielded similar results (A. Puoti, personal communication).

Through our analysis of each stage of worm development, we uncovered novel expression data for several genes whose expression patterns have only been partially characterized, including skr-7 and aex-3. In accordance with previous observations, GFP::SKR-7 is widely expressed in L1 and L2 larvae (Figure 6M and data not shown), but is not apparent in L3, L4 or adult animals (43). We also detected GFP::SKR-7 throughout embryos (Figure 6L). This embryonic expression pattern has not been reported, but is consistent with previous unpublished observations (K. Namayaka, personal communication). Iwasaki et al. (44) have shown that aex-3 is expressed in nearly all neurons in adults. Our Gene Catchr-derived GFP::AEX-3 expression pattern extends these results by demonstrating that AEX-3 accumulates in many neurons at all stages of the C.elegans life cycle (Figure 5T–Y).

We did not detect GFP in 4 of 16 transgenic lines: gfp::mes-6, tra-2::gfp, gfp::F56F10.3 and gfp::mab-7. No previous reports of expression of translational reporters exist for these genes (Table 2). Failure to detect GFP may be due to low protein levels. For instance, tra-2 is translationally repressed through elements in its 3′-UTR (45) which are retained in the Gene Catchr tra-2::gfp construct. It is therefore probable that translational downregulation accounts for our inability to detect TRA2::GFP. The ability of our tra-2 transgene to rescue a tra-2 mutant (Figure 7F and G) indicates, however, that it is expressed at physiologically relevant levels too low for us to visualize.

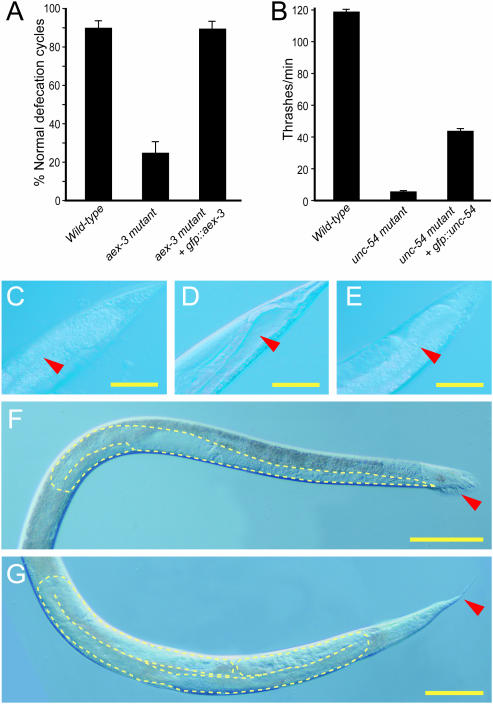

Figure 7.

Rescuing activity of representative Gene Catchr-generated transgenes. (A and C–E) Rescue of aex-3 mutants; (B) rescue of unc-54 mutants; (F and G) rescue of tra-2 mutants. (A) Percentage of successful defecation cycles of wild-type worms, aex-3 mutants and aex-3 mutants carrying gfp::aex-3 transgene. Note that the rate of successful defecation among transgenic animals is equal to that of wild-type. In each case, the mean of 60 defecation cycles among four animals for each of two independent transgenic lines was measured. Intestinal lumen (indicated by the red arrowhead) of adult wild-type worms (C), aex-3 mutants (D) and aex-3 mutants carrying gfp::aex-3 (E). Note the absence of the constipated phenotype in mutants containing a transgene (E) compared with mutants lacking a transgene (D). (B) Rescue of unc-54 mutants: mobility of wild-type worms, unc-54 mutants, and unc-54 mutants carrying gfp::unc-54 measured by mean number of thrashes per minute in M9 buffer. Wild-type (40) and unc-54 (40) mutant worms were counted. For unc-54 mutants carrying gfp::unc-54, 20 worms were counted from each of four independent transgenic lines and the mean was taken. Movement of transgenic animals was restored to 37% of wild-type, compared with 5% of wild-type in unc-54 mutants lacking a transgene. (A and B) Error bars represent standard error. (F) tra-2 mutant XX hermaphrodite transformed into a pseudomale with male one-armed gonad morphology (outlined in yellow) and male-like tail anatomy (indicated by the red arrowhead). (G) Rescue of the soma of tra-2 mutant XX animals carrying tra-2::gfp. Note the hermaphrodite whip-like tail anatomy (indicated by the red arrowhead) and the two-armed gonad (outlined in yellow). (C–G) Scale bars represent 50 µm.

Knowledge of the precise subcellular localization of a protein is essential for the understanding of its function. Reporter-fusions generated from ongoing large-scale expression pattern analysis projects in C.elegans generally fail to provide information about protein localization. In contrast, the translational reporter-fusions generated using the Gene Catchr system provide the opportunity to analyze the subcellular localization of proteins of interest. We find that fusion proteins expressed from Gene Catchr-derived transgenes are accurately localized. As expected for a small GTPase (46), GFP::LET-60 localizes, in part, to the periphery of cells in embryos (Figure 5H) and during later stages of development (data not shown). This report represents the first account of embryonic LET-60 protein expression. The Gene Catchr-derived GFP::UNC-54, GFP::SNR-1 and COL-19::GFP fusion proteins also localize to the appropriate cellular compartments: GFP::UNC-54 to myofilaments of body wall muscles (Figure 5F and G), COL-19::GFP to the lateral alae (Figure 6A) and circumferential annular rings (data not shown) of the cuticle, and GFP::SNR-1 to the nucleus (Figure 5N–S). The subcellular localization patterns produced from Gene Catchr-derived transgenes correspond to those reported previously by both antibody staining and translational fusion constructs (http://www.wormbase.org and references therein).

Collectively, the results obtained from our expression pattern analyses show that Gene Catchr-derived reporter-fusions recapitulate endogenous gene expression patterns, and are properly localized within cells. By analyzing each developmental stage, we have described complete expression patterns for several genes that were previously only partially characterized. Further, we have uncovered novel protein expression data for a number of genes.

Mutant rescue

One concern when tagging genes is that the addition of a tag can disrupt gene function or cause misexpression or mislocalization of the tagged-gene product. To determine if the fusion proteins produced from Gene Catchr-derived transgenes retain the function of the corresponding endogenous proteins, we assayed the ability of gfp::aex-3, tra-2::gfp and gfp::unc-54 to rescue the phenotypes of corresponding mutants (Figure 7, for mutant genotypes see Materials and Methods).

We obtained full rescue of aex-3 mutants and full somatic rescue of tra-2 mutants. aex-3 is required for certain aspects of the C.elegans defecation cycle and aex-3 mutants are constipated (47). Presence of gfp::aex-3 fully rescued the defecation defect as well as the constipated phenotype (Figure 7A and C–E). tra-2 functions in the sex determination pathway to specify hermaphrodite development (48,49). tra-2 mutant XX hermaphrodites are transformed into infertile pseudomales with male one-armed gonad morphology and male-like tail anatomy (48) (Figure 7F). In our rescue assays, the soma of tra-2 mutant XX animals carrying tra-2::gfp was completely feminized (rescued) as evidenced by the hermaphrodite whip-like tail anatomy and the two-armed gonad (Figure 7G).

unc-54 is the major myosin heavy chain in C.elegans and is required for locomotion (50). We obtained partial rescue of the semi-paralyzed phenotype of unc-54 mutants (Figure 7B). This level of rescue is comparable with that observed in a previous report using cosmid DNA containing the full unc-54 gene and extensive flanking DNA (51). Partial rescue is a common phenomenon owing to the nature in which exogenous DNA is maintained in C.elegans. Transgenes in C.elegans are generally transmitted as large, repetitive extrachromosomal arrays composed of many copies of the injected DNA (26,52). Owing to the high number of copies of the transgene in an extrachromosomal array, total transgene expression can be elevated relative to that of the corresponding endogenous gene (51), which in some cases can interfere with gene function. In addition, transgenes are not necessarily expressed in every cell in which they may be required owing to mosaic loss of the extrachromosomal array (52). One way around these limitations is to generate low-copy integrated transgenic lines by microparticle bombardment (53,54) (Discussion).

The mutant rescue data demonstrate that our transgenes retain endogenous gene function, providing strong evidence that the expression and localization of the tagged-gene products recapitulate that of the corresponding endogenous gene products. Gene Catchr-derived transgenes are therefore useful for both gene expression studies and as rescuing constructs, serving as important tools for genetic analyses.

DISCUSSION

Methods for analyzing the expression of many genes inevitably sacrifice resolution, accuracy or completeness for the goal of obtaining many expression patterns. Reporter constructs are widely used to analyze expression patterns in C.elegans, but as conventionally produced, they may lack regulatory elements required to recapitulate the expression of corresponding endogenous genes. To overcome this limitation, we developed Gene Catchr as a flexible method to generate reporter constructs that preserve as much as possible of the original regulatory context of the target gene. The method's exploitation of YHR provides great flexibility with respect to the size and endpoints of the target region, which facilitates inclusion of the complete ORF, distal regulatory elements, and those located within introns and UTRs. Moreover, Gene Catchr allows the study of genes in operons as they are regulated in their native context. This is important, as ∼2600 genes in C.elegans are contained in operons (55).

The flexibility offered by Gene Catchr extends to the choice of tag, the site of its insertion and the source of genomic DNA. Instead of the GFP tag that we have used for studying expression and localization patterns, a ‘tandem affinity purification’ (TAP) tag can be inserted to facilitate purification of complexes containing the protein of interest and allow mapping of protein–protein interactions in vivo. Alternatively, the recently described ‘localization and affinity purification’ (LAP) tag (56), consisting of GFP and S-peptide tags, would serve the dual purpose of allowing visualization and purification of the target protein. Tag position is an important consideration in generating reporter transgenes: a large-scale study of yeast protein localization found that a C-terminal tag altered the localization of 95% of proteins containing C-terminal localization signals (5). The loop-out tagging strategy employed by Gene Catchr allows the site of tag insertion to be chosen so as to avoid disrupting functional motifs within the target protein. Moreover, this strategy, unlike one that relies on a selectable marker located downstream of the tag, introduces no other extraneous sequence which might affect gene regulation. Gene Catchr is applicable to any organism whose genome is represented by YAC sets, including human, mouse, Drosophila and others (57–59). It is useful to note that while Gene Catchr takes advantage of YACs as a convenient source of DNA, it is not restricted to YACs; any DNA fragment (such as a plasmid, cosmid, BAC or PCR product) can be used with appropriate manipulation. In addition to the numerous features that Gene Catchr offers, our constructs represent a useful library of individually cloned and tagged genes for applications such as transgenic complementation assays. Further, using the Gene Catchr method, one can generate mutations within transgenes in order to analyze gene function. To this end, we have exploited the Gene Catchr method to create deletions in a tra-1 transgene that have led to important insights into TRA-1 function (M. Schvarzstein and K. Dawson, personal communication). In view of the impracticality of routine gene targeting in C.elegans, the Gene Catchr method represents the best way to manipulate genes in a manner that preserves their endogenous context. Gene Catchr constructs might prove useful substrates to improve recombination efficiency of gene targeting experiments as they contain extensive regions of homology to endogenous loci. Previous studies have shown that recombination efficiency is dependent on length of homology (60). Thus, as well as producing accurate expression data, Gene Catchr derived transgenes can be used as genetic tools. Our system is adaptable to different sizes and sources of genomic region, tags, tag insertion sites and organisms.

Certain challenges were encountered and addressed during the development of the Gene Catchr system. In a small number of cases, the YACs in our collection did not appear to contain the predicted target region. Alternative YACs spanning the same region were available in each such case. Four target regions were refractory to the standard cloning method. By implementing an alternative cloning approach, we successfully cloned all of these target regions. Application of either the standard or alternative cloning method allowed us to clone 35 of 35 attempted target regions. In some cases, the presence of background colonies after the cloning and tagging yeast transformations required that many colonies be screened in order to detect positives. For instance, in the tagging step, background colonies may arise owing to gene conversion of the genomic ura3 mutant locus by the wild-type URA3 copy in the targeted-tag. A yeast strain deleted for the entire URA3 locus would be an ideal host, but we were limited to the genetic background of the AB1380 yeast strain in which the YAC library was made. In AB1380, the ura3 mutation is caused by insertion of a transposable element (61). Despite this limitation, the PCR detection method for identifying positives is simple, efficient and highly sensitive, making the screening of sufficiently large numbers of clones trivial. Upon introduction of the targeted-tag, we observed the persistence of untagged plasmids in the yeast host which interfered with subsequent recovery of the tagged construct. We successfully recovered tagged constructs by implementing an exceptional cytoduction step, in which tagged plasmids were transferred to a new yeast host. Alternatively, one could use a prolonged positive selection protocol in order to isolate the desired plasmid (62). Both methods are equally straightforward and efficient. Finally, generation of transgenic worms by microinjection often leads to germline silencing and/or overexpression of transgenes. To overcome these limitations, and to increase our potential to generate low-copy integrated transgenic lines, we are currently using ballistic transformation (53,54).

We are implementing methods to create a high-throughput Gene Catchr system. We have optimized 96-well format protocols for linker and tag synthesis, diagnostic PCR and cloning transformations. For efficient large-scale primer design, we have developed a bioinformatics program in collaboration with the Center for Computational Biology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Our database contains precalculated primer sequences for cloning and tagging all predicted genes, according to the current annotation of the C.elegans genome. Furthermore, the program predicts protein localization motifs that may affect choice of tag location, and produces the sequence of Gene Catchr-generated constructs in a GenBank-compatible format. Given our success rate of 83–100% at each stage of cloning and tagging so far, we estimate that ∼70% of C.elegans genes will be amenable to the Gene Catchr technique. This is comparable with an ongoing project in which C.elegans promoters are being cloned into Gateway™ vectors. In this study, 73% of promoter fragments attempted were successfully cloned (14). The Gene Catchr method is useful for detailed analyses of a small number of genes, and can also be scaled up in order to study multiple genes in parallel.

In summary, we have developed a method for generating translational reporter-fusions that are functional and recapitulate endogenous gene expression. Moreover, we have used this method to uncover novel expression data for several genes. The accuracy of the expression data that we have presented demonstrates that Gene Catchr has the potential to be a powerful tool for the study of gene expression, regulation and function.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Alan Coulson for providing YAC strains, Chris Beh for the yeast strain CBY668, Christopher Raymond for recombination subcloning reagents, and Tim Hughes' laboratory for primers. We thank Michael Schertzberg and Sandra Monkewich for technical assistance. We are grateful to Brigitte Lavoie for extremely valuable suggestions, Peter Roy and his laboratory for useful discussions, and Brenda Andrews' laboratory for plasmids, reagents and advice. We thank Peter Roy, Brigitte Lavoie, Henry Krause and Howard Lipshitz for critical reading of the manuscript. Work on this project not described in this paper has been greatly facilitated by the Bioinformatics tool developed by Ted Chiang at the Center for Computational Biology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto. Nematode strains used in this work were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the NIH National Center for Research Resources. This project was funded by Genome Canada. H.E.S. was supported by NSERC and Ontario Graduate Scholarships. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Genome Canada.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sulston J.E., Horvitz H.R. Post-embryonic cell lineages of the nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 1977;56:110–156. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sulston J.E., Schierenberg E., White J.G., Thomson J.N. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimble J., Hirsh D. The postembryonic cell lineages of the hermaphrodite and male gonads in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 1979;70:396–417. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90035-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.C.elegans Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence of the nematode C.elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huh W.K., Falvo J.V., Gerke L.C., Carroll A.S., Howson R.W., Weissman J.S., O'Shea E.K. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 2003;425:686–691. doi: 10.1038/nature02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clyne P.J., Brotman J.S., Sweeney S.T., Davis G. Green fluorescent protein tagging Drosophila proteins at their native genomic loci with small P elements. Genetics. 2003;165:1433–1441. doi: 10.1093/genetics/165.3.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morin X., Daneman R., Zavortink M., Chia W. A protein trap strategy to detect GFP-tagged proteins expressed from their endogenous loci in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:15050–15055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261408198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett P.L., Fleming J.T., Gobel V. Targeted gene alteration in Caenorhabditis elegans by gene conversion. Nature Genet. 2004;36:1231–1237. doi: 10.1038/ng1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hope I.A. ‘Promoter trapping’ in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1991;113:399–408. doi: 10.1242/dev.113.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lynch A.S., Briggs D., Hope I.A. Developmental expression pattern screen for genes predicted in the C.elegans genome sequencing project. Nature Genet. 1995;11:309–313. doi: 10.1038/ng1195-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mounsey A., Bauer P., Hope I.A. Evidence suggesting that a fifth of annotated Caenorhabditis elegans genes may be pseudogenes. Genome Res. 2002;12:770–775. doi: 10.1101/gr208802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassata G., Kagoshima H., Pretot R.F., Aspock G., Niklaus G., Burglin T.R. Rapid expression screening of Caenorhabditis elegans homeobox open reading frames using a two-step polymerase chain reaction promoter-gfp reporter construction technique. Gene. 1998;212:127–135. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hope I.A., Stevens J., Garner A., Hayes J., Cheo D.L., Brasch M.A., Vidal M. Feasibility of genome-scale construction of promoter:reporter gene fusions for expression in Caenorhabditis elegans using a multisite gateway recombination system. Genome Res. 2004;14:2070–2075. doi: 10.1101/gr.2463804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dupuy D., Li Q.R., Deplancke B., Boxem M., Hao T., Lamesch P., Sequerra R., Bosak S., Doucette-Stamm L., Hope I.A., et al. A first version of the Caenorhabditis elegans Promoterome. Genome Res. 2004;14:2169–2175. doi: 10.1101/gr.2497604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGhee J., Krause M.W. Transcription Factors and Trascriptional Regulation. In: Riddle D.L., Blumenthal T., Meyer B.J., Priess J.R., editors. C.elegans II. Plainview, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1997. pp. 147–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okkema P.G., Harrison S.W., Plunger V., Aryana A., Fire A. Sequence requirements for myosin gene expression and regulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1993;135:385–404. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuersten S., Goodwin E.B. The power of the 3′-UTR: translational control and development. Nature Rev. Genet. 2003;4:626–637. doi: 10.1038/nrg1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun-Wada G.H., Kamei Y., Wada Y., Futai M. Regulatory elements directing gut expression of the GATA6 gene during mouse early development. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 2004;135:165–169. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Hir H., Nott A., Moore M.J. How introns influence and enhance eukaryotic gene expression. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:215–220. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkie G.S., Dickson K.S., Gray N.K. Regulation of mRNA translation by 5′- and 3′-UTR-binding factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:182–188. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00051-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke D.T., Carle G.F., Olson M.V. Cloning of large segments of exogenous DNA into yeast by means of artificial chromosome vectors. Science. 1987;236:806–812. doi: 10.1126/science.3033825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawkins N.C., Garriga G., Beh C.T. Creating precise GFP fusions in plasmids using yeast homologous recombination. Biotechniques. 2003;34:74–78. doi: 10.2144/03341st03. 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Longtine M.S., McKenzie A., III, Demarini D.J., Shah N.G., Wach A., Brachat A., Philippsen P., Pringle J.R. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77:71–94. doi: 10.1093/genetics/77.1.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Church D.L., Guan K.L., Lambie E.J. Three genes of the MAP kinase cascade, mek-2, mpk-1/sur-1 and let-60 ras, are required for meiotic cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development. 1995;121:2525–2535. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.8.2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mello C.C., Kramer J.M., Stinchcomb D., Ambros V. Efficient gene transfer in C.elegans: extrachromosomal maintenance and integration of transforming sequences. EMBO J. 1991;10:3959–3970. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04966.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granato M., Schnabel H., Schnabel R. pha-1, a selectable marker for gene transfer in C.elegans. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1762–1763. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.9.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnabel H., Schnabel R. An organ-specific differentiation gene, pha-1, from Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1990;250:686–688. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4981.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gietz R.D., Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones J.S., Prakash L. Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae selectable markers in pUC18 polylinkers. Yeast. 1990;6:363–366. doi: 10.1002/yea.320060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman C.S., Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeMarini D.J., Creasy C.L., Lu Q., Mao J., Sheardown S.A., Sathe G.M., Livi G.P. Oligonucleotide-mediated, PCR-independent cloning by homologous recombination. Biotechniques. 2001;30:520–523. doi: 10.2144/01303st02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raymond C.K., Sims E.H., Olson M.V. Linker-mediated recombinational subcloning of large DNA fragments using yeast. Genome Res. 2002;12:190–197. doi: 10.1101/gr.205201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alani E., Cao L., Kleckner N. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics. 1987;116:541–545. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.541.test. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dutcher S.K. Internuclear transfer of genetic information in kar1-1/KAR1 heterokaryons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1981;1:245–253. doi: 10.1128/mcb.1.3.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sigurdson D.C., Gaarder M.E., Livingston D.M. Characterization of the transmission during cytoductant formation of the 2 micrometers DNA plasmid from Saccharomyces. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1981;183:59–65. doi: 10.1007/BF00270139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shashikant C.S., Carr J.L., Bhargava J., Bentley K.L., Ruddle F.H. Recombinogenic targeting: a new approach to genomic analysis—a review. Gene. 1998;223:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodgkin J. Molecular cloning and duplication of the nematode sex-determining gene tra-1. Genetics. 1993;133:543–560. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbee S.A., Lublin A.L., Evans T.C. A novel function for the Sm proteins in germ granule localization during C.elegans embryogenesis. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1502–1506. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park Y.S., Kramer J.M. The C.elegans sqt-1 and rol-6 collagen genes are coordinately expressed during development, but not at all stages that display mutant phenotypes. Dev. Biol. 1994;163:112–124. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thein M.C., McCormack G., Winter A.D., Johnstone I.L., Shoemaker C.B., Page A.P. Caenorhabditis elegans exoskeleton collagen COL-19: an adult-specific marker for collagen modification and assembly, and the analysis of organismal morphology. Dev. Dyn. 2003;226:523–539. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenquist T.A., Kimble J. Molecular cloning and transcript analysis of fem-3, a sex-determination gene in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genes Dev. 1988;2:606–616. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamanaka A., Yada M., Imaki H., Koga M., Ohshima Y., Nakayama K. Multiple Skp1-related proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans: diverse patterns of interaction with Cullins and F-box proteins. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:267–275. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00657-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwasaki K., Staunton J., Saifee O., Nonet M., Thomas J.H. aex-3 encodes a novel regulator of presynaptic activity in C.elegans. Neuron. 1997;18:613–622. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80302-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodwin E.B., Okkema P.G., Evans T.C., Kimble J. Translational regulation of tra-2 by its 3′ untranslated region controls sexual identity in C.elegans. Cell. 1993;75:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80074-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han M., Sternberg P.W. let-60, a gene that specifies cell fates during C.elegans vulval induction, encodes a ras protein. Cell. 1990;63:921–931. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90495-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas J.H. Genetic analysis of defecation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1990;124:855–872. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.4.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hodgkin J.A., Brenner S. Mutations causing transformation of sexual phenotype in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1977;86:275–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuwabara P.E., Okkema P.G., Kimble J. tra-2 encodes a membrane protein and may mediate cell communication in the Caenorhabditis elegans sex determination pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1992;3:461–473. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.4.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacLeod A.R., Waterston R.H., Fishpool R.M., Brenner S. Identification of the structural gene for a myosin heavy-chain in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Mol. Biol. 1977;114:133–140. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fire A., Waterston R.H. Proper expression of myosin genes in transgenic nematodes. EMBO J. 1989;8:3419–3428. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08506.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stinchcomb D.T., Shaw J.E., Carr S.H., Hirsh D. Extrachromosomal DNA transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1985;5:3484–3496. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Praitis V., Casey E., Collar D., Austin J. Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2001;157:1217–1226. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilm T., Demel P., Koop H.U., Schnabel H., Schnabel R. Ballistic transformation of Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene. 1999;229:31–35. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blumenthal T., Evans D., Link C.D., Guffanti A., Lawson D., Thierry-Mieg J., Thierry-Mieg D., Chiu W.L., Duke K., Kiraly M., et al. A global analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans operons. Nature. 2002;417:851–854. doi: 10.1038/nature00831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cheeseman I.M., Niessen S., Anderson S., Hyndman F., Yates J.R., III, Oegema K., Desai A. A conserved protein network controls assembly of the outer kinetochore and its ability to sustain tension. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2255–2268. doi: 10.1101/gad.1234104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cai H., Kiefel P., Yee J., Duncan I. A yeast artificial chromosome clone map of the Drosophila genome. Genetics. 1994;136:1385–1399. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.4.1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen D., Chumakov I., Weissenbach J. A first-generation physical map of the human genome. Nature. 1993;366:698–701. doi: 10.1038/366698a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nusbaum C., Slonim D.K., Harris K.L., Birren B.W., Steen R.G., Stein L.D., Miller J., Dietrich W.F., Nahf R., Wang V., et al. A YAC-based physical map of the mouse genome. Nature Genet. 1999;22:388–393. doi: 10.1038/11967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deng C., Capecchi M.R. Reexamination of gene targeting frequency as a function of the extent of homology between the targeting vector and the target locus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:3365–3371. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.8.3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rose M., Winston F. Identification of a Ty insertion within the coding sequence of the S. cerevisiae URA3 gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1984;193:557–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00382100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vidalain P.O., Boxem M., Ge H., Li S., Vidal M. Increasing specificity in high-throughput yeast two-hybrid experiments. Methods. 2004;32:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frengen E., Weichenhan D., Zhao B., Osoegawa K., van Geel M., de Jong P.J. A modular, positive selection bacterial artificial chromosome vector with multiple cloning sites. Genomics. 1999;58:250–253. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shizuya H., Birren B., Kim U.J., Mancino V., Slepak T., Tachiiri Y., Simon M. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:8794–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ardizzi J.P., Epstein H.F. Immunochemical localization of myosin heavy chain isoforms and paramyosin in developmentally and structurally diverse muscle cell types of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Biol. 1987;105:2763–2770. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Graham P.L., Johnson J.J., Wang S., Sibley M.H., Gupta M.C., Kramer J.M. Type IV collagen is detectable in most, but not all, basement membranes of Caenorhabditis elegans and assembles on tissues that do not express it. J. Cell Biol. 1997;137:1171–1183. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.5.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dent J.A., Han M. Post-embryonic expression pattern of C.elegans let-60 ras reporter constructs. Mech. Dev. 1998;72:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abrahante J.E., Miller E.A., Rougvie A.E. Identification of heterochronic mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans. Temporal misexpression of a collagen:green fluorescent protein fusion gene. Genetics. 1998;149:1335–1351. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.3.1335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karabinos A., Schulze E., Klisch T., Wang J., Weber K. Expression profiles of the essential intermediate filament (IF) protein A2 and the IF protein C2 in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech. Dev. 2002;117:311–314. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patterson G.I., Koweek A., Wong A., Liu Y., Ruvkun G. The DAF-3 Smad protein antagonizes TGF-beta-related receptor signaling in the Caenorhabditis elegans dauer pathway. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2679–2690. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.20.2679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.