Abstract

We identified a new type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) from two community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains. The novel element, designated type IV SCCmec, had a unique combination of the class B mec gene complex and the type 2 ccr gene complex and was much smaller in size (21 to 24 kb) than previously identified SCCmec elements of hospital-acquired MRSA. Consistent with the strains' susceptibilities to various non-β-lactam antibiotics, the type IV SCCmec was devoid of any antibiotic resistance genes other than the mecA gene.

Since the first discovery of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in 1961 in England, MRSA has become one of the most prevalent pathogens that cause nosocomial infections (13). MRSA produces a specific penicillin-binding protein (PBP) called PBP 2′ (or PBP 2a) that possesses reduced affinities for binding to β-lactam antibiotics (2, 7, 22). PBP 2′ is encoded by the mecA gene, which is carried by a large mobile genetic element that is designated staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) and that is integrated on the chromosomes of MRSA strains isolated from hospitals in various countries throughout the world (11, 12, 14, 15).

Recently, MRSA infections have increasingly been reported among groups of patients with no apparent connection to hospitals (4). Those strains, designated community-acquired MRSA (C-MRSA) strains, have been reported in various countries such as Australia (16, 18), New Zealand (19), the United Kingdom (20), Canada (5), and the United States (6, 8). The death of four children caused by C-MRSA strains has alerted us to the threat of latent dissemination of highly virulent C-MRSA strains in the community in the United States (3).

In contrast to hospital-acquired MRSA (H-MRSA), C-MRSA is characteristically susceptible to many antibiotics (3, 21), but it remains unclear whether C-MRSA is a descendant of H-MRSA or was born and evolved independently of the hospital environment (4). In order to understand the evolutionary relationship between C-MRSA and H-MRSA, we determined the entire nucleotide sequences of the SCCmec elements integrated into the chromosomes of two C-MRSA clinical strains. Strain CA05 (JCSC1968) was isolated from the joint fluid of a patient with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, and strain 8/6-3P (JCSC1978) was isolated from the perineum of another patient (10).

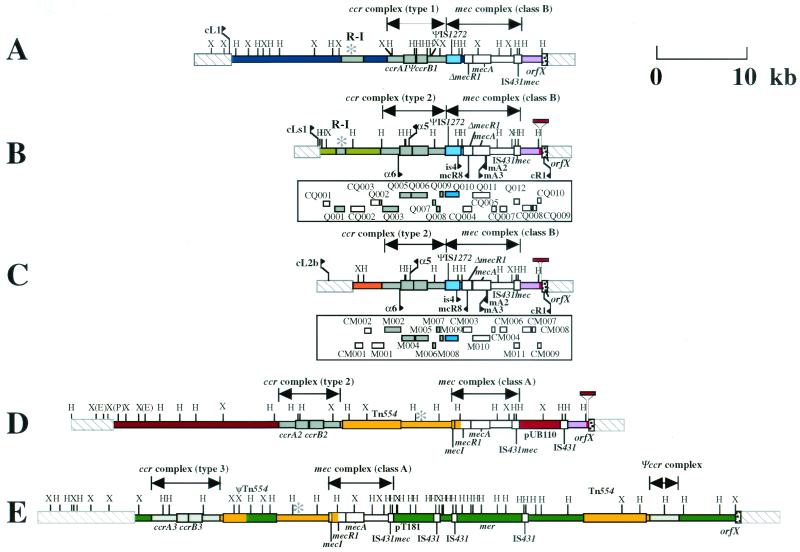

We amplified DNAs encompassing the entire SCCmec sequence by long-range PCR with several sets of primers, as follows. The region from the left extremity to the ccr genes (L-C region) was covered by primer sets α5 and cLs1 (CA05) or CL2b (8/6-3P) (Fig. 1). Primers α6 and mcR8 were used to cover the middle part (from the region just upstream of ccrA to mecR1; the C-M region). Two overlapping primer sets (primers is4 and mA2 and primers mA3 and cR1) were used to cover the right extremities (from IS431mec to orfX; the I-R region) (Fig. 1) (11, 12, 14). The rest of the element was amplified and sequenced with primers as described previously (11, 12, 14). The PCR products were purified with a High Pure PCR product purification kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), and their nucleotide sequences were determined as described previously (9).

FIG. 1.

Structure of the SCCmec elements identified from C-MRSA strains in comparison with the three types of SCCmec elements. (A) Type I SCCmec carried by NCTC 10442. (B) Type IV SCCmec carried by strain CA05 (subtype a). (C) Type IV SCCmec carried by strain 8/6-3P (subtype b). (D) Type II SCCmec carried by N315. (E) Type III SCCmec carried by 85/2082. The ORFs of greater than 200 nucleotides in six possible reading frames of type IV SCCmec elements are illustrated in the squares under the bars that represent essential genes and restriction sites for HindIII and XbaI. Differences in coloration correspond to differences in the nucleotide sequences. Color codes are as follows: white, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are conserved in all four types of SCCmec elements with greater than 99% amino acid identities; gray, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are conserved in four types of SCCmec with amino acid identities of 46 to 98%; magenta, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are common to type I and type II SCCmec elements; yellow, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are common to type II and type III SCCmec elements; blue, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are unique to type I SCCmec; red, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are unique to type II SCCmec; green, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are unique to type III SCCmec, light green, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are unique to type IVa SCCmec; and orange, ORFs or the parts of ORFs that are unique to type IVb SCCmec. The locations of primers used for amplification of the type IV SCCmec are indicated by arrows: they are primers α5 (5′-TGTTAAGTATATTGCACTTTATGATTCAATGCCT-3′), cLs1 (5′-TGCCAATCACAGTTCAATCAATT-3′), α6 (5′-ATTAGCCGATTTGGTAATTGAA-3′), mCR8 (5′-ATATTCCCGTATGAAAAACAGGACTTGAACTTGCA-3′), and CL2b (ATATTCCCGATAGAAAAACAGGACTTGAACTTGCA) and previously described primers is4, mA2, mA3, and cR1 (11, 12, 14). The entire nucleotide sequences of the type IV SCCmec elements are available in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession no. AB063172 (subtype a) and AB063173 (subtype b). H, HindIII, X, XbaI; E, EcoRI; P, Pst1.

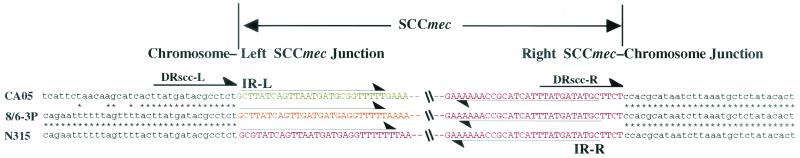

Figure 1 illustrates the genomic organizations of the SCCmec elements identified from the two C-MRSA strains in comparison with the three extant types of SCCmec. The SCCmec elements of strains CA05 and 8/6-3P were 24,248 and 20,920 bp, respectively, and were much smaller (34 to 67 kb) than three types of SCCmec elements identified from H-MRSA strains (12). Both elements were found to be integrated at the integration site for SCCmec, attBscc, which is found inside orfX, which has an unknown function and is located near the origin of replication of the S. aureus chromosome (12, 15). The SCCmec elements shared a pair of 15-bp direct repeat sequences: one (DRscc-R) at the right extremities and the other (DRscc-L) on the chromosome region abutting the left termini of the elements (shown as thick arrows in Fig. 2). Degenerate inverted repeats were also found in the extremities of the two SCCmec elements (shown by thin arrows in Fig. 2). The authenticity of the SCCmec boundaries was vindicated by using a previously described method (14); i.e., by confirming that the element was precisely cut out from the chromosomes of the two C-MRSA strains, regenerating attBscc in the chromosomes of the cell populations from which it was excised.

FIG. 2.

Chromosome-SCCmec junction sequences of type IV SCCmec. The nucleotide sequences around the left and right boundaries of the SCCmec elements of CA05 and 8/6-3P are aligned with those of type II SCCmec. Thin arrows indicate inverted repeats IR-L and IR-R at both extremities of SCCmec elements. Thick arrows indicate direct repeats DRscc-L and DRscc-R.

The nucleotide sequences of the L-C regions of the two SCCmec elements differed from each other, but otherwise, they shared the same features: type 2 ccr gene complexes, the class B mec gene complexes (IS1272-ΔmecR1-mecA-IS431), and the I-R region that was 99.9% identical to that of type II SCCmec elements (Fig. 1). This combination of ccr and mec gene complexes was a novel one. That is, the class B mec gene complex has been found to be in close linkage with the type 1 ccr gene complex in type I SCCmec (12). However, the ccr gene complexes of the novel SCCmec elements were more similar to the type 2 gene complex than to the type 1 ccr gene complex: the amino acid identities between the novel CcrA proteins and the type 2 CcrA (CcrA2) and type 1 CcrA (CcrA1) proteins were about 98 and 75%, respectively; and those between the novel CcrB proteins and the CcrB2 and CcrB1 proteins were 97 to 99 and 72 to 81%, respectively (Table 1). Accordingly, we classified the genes as variants of ccrA2 and ccrB2 by designating them the ccrA2.1 and ccrA2.2 genes and the ccrB2.1 and ccrB2.2 genes, respectively (Table 1). As shown in Table 1, the predicted proteins encoded by the open reading frames (ORFs) surrounding the ccrA and ccrB genes also had significantly higher degrees of similarity to those of the type 2 gene complex than to those of the type 1 ccr gene complex. On the basis of this unique combination of the two complexes, we named the novel SCCmec elements type IV SCCmec and assigned the designations subtypes IVa and IVb to the individual elements of CA05 and 8/6-3P, respectively, on the basis of their unique nucleotide sequences in the L-C region (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

ORFs in SCCmec’s of CA05 and 8/6-3P

| Strain (element) and ORFa | Location (position)b | Size (bp) of gene | Description of gene product |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA05 (JCSC1968) (type IV SCCmec subtype a) | |||

| CQ001 | Complement (1280-1900) | 621 | Hypothetical protein |

| Q001 | 2653-3657 | 1,005 | Hypothetical protein |

| CQ002 | Complement (4281-5771) | 1,491 | Hypothetical protein |

| CQ003 | Complement (6389-7438) | 1,050 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q002 | 7577-7867 | 291 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q003 | 7867-9654 | 1,788 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q005 | 9888-11237 | 1,350 (ccrA2.1) | Cassette chromosome recombinase A |

| Q006 | 11259-12887 | 1,629 (ccrB2.1) | Cassette chromosome recombinase B |

| Q007 | 13409-13759 | 351 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q008 | 13846-14157 | 312 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q009 | 14169-14678 | 510 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| Q010 | 14679-16337 | 1,659 | Putative transposase of IS 1272 |

| CQ004 | Complement (16560-17546) | 987 (ΔmecR1) | Truncated signal transducer protein MecR1 |

| Q011 | 17646-19652 | 2,007 (mecA) | PBP 2′ |

| CQ005 | Complement (19698-20126) | 429 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| CQ007 | Complement (20223-20966) | 744 (ugpQ) | Glycerophosphoryldiester phosphodiesterase |

| Q012 | 22268-22942 | 675 tnp | Transposase for insertion sequence-like element IS431mec |

| CQ008 | Complement (22974-23213) | 240 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| CQ009 | Complement (23628-24659) | 1,032 | Truncated conserved hypothetical protein |

| CQ010 | Complement (24509-24883) | 375 | Truncated conserved hypothetical protein |

| (CQ011) | Complement (25205-25684) | 480 | OrfX |

| 8/6-3P (JCSC1978) (type IV SCCmec subtype b) | |||

| CM001 | Complement (325-1446) | 1,122 | Hypothetical protein |

| CM002 | Complement (1424-2194) | 771 | Hypothetical protein |

| M001 | 2311-3741 | 1,431 | Hypothetical protein |

| M002 | 3861-5651 | 1,791 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| M004 | 5885-7234 | 1,350 (ccrA2.2) | Cassette chromosome recombinase A |

| M005 | 7256-8884 | 1,629 (ccrB2.2) | Cassette chromosome recombinase B |

| M006 | 9406-9756 | 351 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| M007 | 9843-10154 | 312 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| M008 | 10166-10675 | 510 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| M009 | 10676-12334 | 1,659 | Putative transposase of IS1272 |

| CM003 | Complement (12557-13543) | 987 (ΔmecR1) | Truncated signal transducer protein MecR1 |

| M010 | 13643-15649 | 2,007 (mecA) | PBP 2′ |

| CM004 | Complement (15695-16123) | 429 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| CM006 | Complement (16220-16963) | 744 (ugpQ) | Glycerophosphoryldiester phosphodiesterase |

| M011 | 18265-18939 | 675 tnp | Transposase for insertion sequence-like element IS431mec |

| CM007 | Complement (18971-19210) | 240 | Conserved hypothetical protein |

| CM008 | Complement (19625-20656) | 1,032 | Truncated conserved hypothetical protein |

| CM009 | Complement (20506-20880) | 375 | Truncated conserved hypothetical protein |

| CM010 | Complement (21204-21683) | 480 | OrfX |

| Homology to ORFs of type I SCCmec

|

Homology to ORFs of type II SCCmec

|

Homology to ORFs of type III SCCmec

|

Homology to ORFs of type IV SCCmec subtype b

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Identityc | Corresponding ORF(s) (size [bp]) | % Identityc | Corresponding ORF(s) (size [bp]) | % Identityc | Corresponding ORF(s) (size [bp]) | % Identityc | Corresponding ORF(s) (size [bp]) |

| 96.4 | E024 (1329) | 72.4 | N053d (861) | 72.4 | Z025d (861) | ||

| 77.8 | CZ002 (1,068) | ||||||

| 46.2 | E025 (297) | 46 | N030 (297) | 45.7 | Z003 (288) | ||

| 77.3 | E026 (1,770) | 85.3 | N031 (1,794) | 66.3 | Z004 (1,569) | 82.4 | M002 (1791) |

| 75 | ccrA1 (1,350) | 97.6 | ccrA2 (1,350) | 72.4 | ccrA3 (1,350) | 98.2 | M004 (1350) |

| 72.4 | ∗ccrB1 (1,152) | 97.4 | ccrB2 (1,629) | 87.5 | ccrB3 (1,629) | 99.3 | M005 (1629) |

| 85.3 | E031 (351) | 88.8 | N041 (351) | 51.3 | Z011 (351) | 100 | M006 (351) |

| 85.4 | E032 (327) | 89.2 | N042 (312) | 47.2 | Z013 (396) | 100 | M007 (312) |

| 97.6 | E033 (510) | 92.7 | N043 (318) | 61.3 | Z014 (522) | 100 | M008 (510) |

| 100 | E034 (1,659) | 100 | M009 (1659) | ||||

| 100 | ΔmecR1NCTC10442 (987) | 100 | mecR1N315 (1,758) | 100 | ΔmecR185/2082 (114) | 100 | |

| 99.9 | mecANCTC10442 (2,007) | 100 | mecAN315 (2,007) | 99.7 | mecA85/2082 (2007) | 100 | |

| 99.3 | CE025 (429) | 100 | CN038 (429) | 100 | CZ029 (429) | 100 | CM004 (429) |

| 100 | CE026 (744) | 100 | CN039 (744) | 100 | CZ030 (744) | 100 | |

| 100 | E040 (675) | 100 | N062 and N070 (675) | 100, 99.6, 99.1, 99.1 | Z035, Z041, Z046, and Z058 (675) | 100 | |

| 100 | CE029 (240) | 100 | CM007 (240) | ||||

| 100 | CE030 (1,296) | 100 | CN050 (1,296) | 100 | CM008 (1032) | ||

| 98.4 | CE030 (1,296) | 98.4 | CN050 (1,296) | 100 | CM009 (375) | ||

| 100 | orfX (480) | 100 | orfX (480) | 100 | orfX (480) | 100 | CM010 (480) |

| 70.3 | E026 (1,770) | 80.7 | N031 (1,794) | 72.1 | Z004 (1,569) | ||

| 75.2 | ccrA1 (1,350) | 96.2 | ccrA2 (1,350) | 73.5 | ccrA3 (1,350) | ||

| 80.6 | ccrB1 (1,152) | 98.2 | ccrB2 (1,629) | 87.1 | ccrB3 (1,629) | ||

| 85.3 | E031 (351) | 88.8 | N041 (351) | 5.3 | Z011 (351) | ||

| 85.4 | E032 (327) | 89.2 | N042 (312) | 4.2 | Z013 (396) | ||

| 97.6 | E033 (510) | 92.3 | N043 (318) | 61.3 | Z014 (522) | ||

| 100 | E034 (1,659) | ||||||

| 100 | ΔmecR1NCTC10442 (987) | 100 | mecR1N315 (1,758) | 100 | ΔmecR185/2082 (114) | ||

| 99.9 | mecANCTC10442 (2,007) | 100 | mecAN315 (2,007) | 99.7 | mecA85/2082 (2,007) | ||

| 99.3 | CE025 (429) | 100 | CN038 (429) | 100 | CZ029 (429) | ||

| 100 | CE026 (744) | 100 | CN039 (744) | 100 | CZ030 (744) | ||

| 100 | E040 (675) | 100 | N062 and N070 (675) | 100, 99.6, 99.1, 99.1 | Z035, Z041, Z046, and Z058 (675) | ||

| 100 | CE029 (240) | ||||||

| 100 | CE030 (1,296) | 100 | CN050 (1,296) | ||||

| 98.4 | CE030 (1,296) | 98.4 | CN050 (1,296) | ||||

| 100 | orfX (480) | 100 | orfX (480) | 100 | orfX (480) | ||

ORFs shown in parentheses were located outside of SCC mec.

The nucleotide position in the nucleotide sequences deposited under DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession no. AB063172 (type IV subtype a) and AB063173 (type IV subtype b).

Identity to amino acid sequences of each ORF.

Incomplete ORFs that are potentially defective genes or pseudogenes containing either a deletion, a nonsense mutation, or a frameshift mutation.

The BLAST and MOTIF programs failed to assign any biological functions to the hypothetical ORFs in the L-C regions of type IV SCCmec elements (1, 17). With their simple genetic organizations, neither a virulence factor nor antibiotic resistance other than that encoded by mecA was found to be encoded by the entire regions of the novel SCCmec elements. This lack of genes encoding resistance to non-β-lactam antibiotics in the type IV SCCmec was consistent with the notable characteristic of C-MRSA; i.e., its susceptibility to various antibiotics except β-lactams (3, 6). In fact, as shown in Table 2, the two strains were susceptible to all the non-β-lactam antibiotics tested.

TABLE 2.

Antibiotic susceptibility profiles of the two C-MRSA strains in comparison with those of H-MRSA strains

| Strain | Type of SCC mec | MIC (mg/liter)a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxacillin | Ampicillin | Ceftizoxime | Imipenem | Erythromycin | Tobramycin | Kanamycin | Tetracycline | ||

| CA05 | IV | 8 | 32 | 128 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 2 | 0.125 |

| 8/6-3P | IV | 8 | 16 | 128 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 0.125 |

| NCTC 10442 | I | 256 | 256 | >512 | 16 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 1 | 128 |

| N315 | II | 16 | 32 | 16 | 1 | >512 | 512 | >512 | 0.125 |

| 85/2082 | III | 32 | 32 | >512 | 0.5 | >512 | 8 | 512 | 128 |

| ATCC 29213b | 0.25 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.03 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.125 | |

The MICs were determined by the agar plate dilution method of the NCCLS.

A methicillin-susceptible S. aureus type strain.

The lack of function of type IV SCCmec other than those for the movement of the element (ccr genes) and methicillin resistance (mecA), together with its small size, may lead to the view that the element has gone through evolutionary refinement as a specific carrier of DNA for methicillin resistance. Furthermore, the lack of superfluous functions may make the element more fit as a mobile genetic element for S. aureus in the community than any other type of SCCmec, for the following reasons. A number of ORFs carried by type I and type II SCCmec elements in their long L-C regions are considered unnecessary for the benefit of the host cells that carry the elements (11, 12). Actually, many of them are mutated or partially deleted and do not seem to be active. Moreover, an ORF for type I SCCmec encoding plasmin-sensitive surface protein may even be hazardous to the host cell because it interferes with the fibrinogen- and fibronectin-binding properties of the host cell (23). Although the type III SCCmec has a short L-C region comparable in size to those of type IV SCCmec elements, the size of the element is extremely large (68 kb) because of the accumulation of multiple genes for resistance to various antibiotics and heavy metals (12). The determinants for resistance to multiple antibiotics carried by the previously studied types of SCCmec elements (type II and type III elements) may be suited for the survival of H-MRSA in the hospital environment, where various antibiotics as well as antiseptics provide selective pressure, but their large sizes and potentially hazardous arrays of exogenous genes may not be suited to MRSA strains in the community, where selective advantage would make strains more inclined to have a higher growth rate and to be better able to colonize humans than to have a multidrug resistance phenotype. From this viewpoint, the type IV SCCmec may be one of the fit SCCmec types that can confer β-lactam resistance to community strains of S. aureus without greatly compromising their competitiveness among the natural flora of humans. Future analyses of many community-acquired strains will be required to test if this hypothesis holds true.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The subtype a and b type IV SCCmec elements have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession no. AB063172 and AB063173, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Core University System Exchange Program under the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, coordinated by the University of Tokyo Graduate School of Medicine and Mahidol University. The study was also partly supported by a grant for International Health Cooperation Research (grant 11C-4) from the Ministry of Health and Welfare of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, D. F., and P. E. Reynolds. 1980. Intrinsic resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics in Staphylococcus aureus. FEBS Lett. 122:275-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1999. Four pediatric deaths from community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—Minnesota and North Dakota, 1997-1999. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 48:707-710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers, H. F. 2001. The changing epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:178-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Embil, J., K. Ramotar, L. Tomance, M. Alfa, J. Conly, S. Cronk, G. Taylor, B. Sutherland, T. Louie, E. Henderson, et al. 1994. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in tertiary care institutions on the Canadian prairies 1990-1992. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 15:646-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gross-Schulman, S., D. Dassey, L. Mascola, and C. Anaya. 1998. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. JAMA 280:421-422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartman, B. J., and A. Tomasz. 1984. Low-affinity penicillin-binding protein associated with beta-lactam resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 158:513-516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herold, B. C., L. C. Immergluck, M. C. Maranan, D. S. Lauderdale, R. E. Gaskin, S. Boyle-Vavra, C. D. Leitch, and R. S. Daum. 1998. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA 279:593-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiramatsu, K., K. Asada, E. Suzuki, K. Okonogi, and T. Yokota. 1991. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the regulator region of mecA gene in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). FEBS Lett. 298:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain, F. M., S. Boyle-Vavra, C. D. Bethel, and R. S. Daum. 2000. Current trends in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus at a tertiary care pediatric facility. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 19:1163-1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, and K. Hiramatsu. 1999. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1449-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito, T., Y. Katayama, K. Asada, N. Mori, K. Tsutsumimoto, C. Tiensasitorn, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1323-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jevons, M. P. 1961. “Celbenin”-resistant staphylococci. Br. Med. J. 124:124-125. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katayama, Y., T. Ito, and K. Hiramatsu. 2000. A new class of genetic element, staphylococcus cassette chromosome mec, encodes methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1549-1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuroda, M., T. Ohta, I. Uchiyama, T. Baba, H. Yuzawa, I Kobayashi, L. Cui, A. Oguchi, K. Aoki, Y. Nagai, J. Lian, T. Ito, M. Kanamori, H. Matsumaru, A. Maruyama, H. Murakami, A. Hosoyama, Y. Mizutani-Ui, N. K. Takahashi, T. Sawano, R. Inoue, C. Kaito, K. Sekimizu, H. Hirakawa, S. Kuhara, S. Goto, J. Yabuzaki, M. Kanehisa, A. Yamashita, K. Oshima, K. Furuya, C. Yoshino, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, N. Ogasawara, H. Hayashi, and K. Hiramatsu. 2001. Whole genome sequencing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 357:1225-1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maguire, G. P., A. D. Arthur, P. J. Boustead, B. Dwyer, and B. J. Currie. 1998. Clinical experience and outcomes of community-acquired and nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a northern Australian hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 38:273-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakai, K., and P. Horton. 1999. PSORT: a program for detecting sorting signals in proteins and predicting their subcellular localization. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24:34-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimmo, G. R., J. Schooneveldt, G. O'Kane, B. McCall, and A. Vickery. 2000. Community acquisition of gentamicin-sensitive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in southeast Queensland, Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3926-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rings Terry, R. F., and S. Lang. 1998. Ethnicity and methicillin-resistant S. aureus in South Auckland. N. Z. Med. J. 24:151.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stacey, A. R., K. E. Endersby, P. C. Chan, and R. R. Marples. 1998. An outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in a rugby football team. Br. J. Sports Med. 32:153-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suggs, A. H., M. C. Maranan, A. Boyle-Vavra, and R. S. Daum. 1999. Methicillin-resistant and borderline methicillin-resistant asymptomatic Staphylococcus aureus colonization in children without identifiable risk factors. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 18:410-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Utsui, Y., and T. Yokota. 1985. Role of an altered penicillin-binding protein in methicillin- and cephem-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 28:397-403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vaudaux, P. E., V. Monzillo, P. Francois, D. P. Lew, T. J. Foster, and B. Berger-Bachi. 1998. Introduction of the mec element (methicillin resistance) into Staphylococcus aureus alters in vitro functional activities of fibrinogen and fibronectin adhesins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:564-570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]