Abstract

A-315675 is a novel, pyrrolidine-based compound that was evaluated in this study for its ability to inhibit A and B strain influenza virus neuraminidases in enzyme assays and influenza virus replication in cell culture. A-315675 effectively inhibited influenza A N1, N2, and N9 and B strain neuraminidases with inhibitor constant (Ki) values between 0.024 and 0.31 nM. These values were comparable to or lower than the Ki values measured for oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071), zanamivir, and BCX-1812, except for the N1 enzymes that were found to be the most sensitive to BCX-1812. The time-dependent inhibition of neuraminidase catalytic activity observed with A-315675 is likely due to its very low rate of dissociation from the active site of neuraminidase. The half times for dissociation of A-315675 from B/Memphis/3/89 and A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) influenza virus neuraminidases of 10 to 12 h are significantly slower than the half times measured for oseltamivir carboxylate (33 to 60 min). A-315675 inhibited the replication of several laboratory strains of influenza virus in cell culture with potencies that were comparable or superior to those for oseltamivir carboxylate and BCX-1812, except for the A/H1N1 viruses that were found to be two- to fourfold more susceptible to BCX-1812. A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate exhibited comparable potencies against a panel of A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 influenza virus clinical isolates, but A-315675 was found to be significantly more potent than oseltamivir carboxylate against the B strain isolates. The favorable in vitro results relative to other clinically effective agents provide strong support for the further investigation of A-315675 as a potential therapy for influenza virus infections.

The influenza virus is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality within the U.S. population. In an average year, between 10 and 20% of the population becomes ill with influenza (5) resulting in roughly 20,000 deaths (8). Annual vaccination plays a role in the prevention of influenza, but variable efficacy in high-risk groups (27) and underutilization by the broader community have limited their contribution to influenza disease management. Safe and effective anti-influenza drugs are clearly needed to treat the segment of the population that suffer from influenza each year. The antiviral drugs amantidine and rimantidine have been available for many years but have not been widely used because of safety concerns, ineffectiveness against B strains of influenza virus, and rapid emergence of resistance (10, 12).

Oseltamivir and zanamivir are two new drugs that were recently approved for the treatment of influenza infections. Both drugs block viral replication by inhibiting the enzymatic activity of the viral neuraminidase (17, 33). Neuraminidase appears to be required for elution of newly synthesized virus from infected cells (25, 26) and may also have a role in allowing the virus to move through the mucus of the respiratory tract, which is rich in N-acetylneuraminic acid-containing molecules (18). Oseltamivir is an oral drug but sometimes causes transient nausea after dosing (14). Zanamivir is administered as an inhaled powder due to its poor oral bioavailability. Both drugs demonstrate some efficacy in reducing symptom severity and duration of illness (13, 29, 32). A third neuraminidase inhibitor, BCX-1812 (also known as RWJ-270201), has entered the clinic for evaluation as an orally administered therapy for influenza (F. Hayden, J. Treanor, R. Qu, and C. Fowler, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1156, 2000). The in vitro properties (2, 3, 30) and preclinical efficacy in animal models (2, 3, 28) for BCX-1812 were recently described. The possible emergence of virus that is resistant to drugs is always a concern for antiviral drug therapy. Although widespread drug resistance has not arisen to date for the neuraminidase inhibitor class, several viruses have been isolated from clinical trials and from in vitro passage studies that are resistant to one or more neuraminidase inhibitors (20). It therefore seems prudent to continue to search for new compounds with improved dosing convenience, therapeutic properties, or different resistance profiles relative to the presently marketed agents.

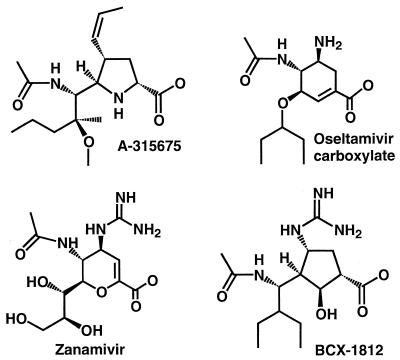

We have previously reported the initial discovery (16) and limited optimization (34) of a novel series of influenza neuraminidase inhibitors containing a pyrrolidine core. Further optimization has led to the discovery of 5-[(1R,2S)-1-(acetylamino)-2-methoxy-2-methylpentyl]-4-[(1Z)-1-propenyl]-(4S,5R)-d-proline (A-315675). The chemical structure of A-315675 is shown in Fig. 1 along with the corresponding structures for zanamivir, oseltamivir carboxylate, and BCX-1812. In this study we report the in vitro characterization of A-315675 relative to its peers in terms of binding affinities to a panel of influenza virus neuraminidases, as well as antiviral potencies against several laboratory-derived influenza viruses and low-passage clinical isolates.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of influenza neuraminidase inhibitors. Oseltamivir carboxylate, BCX-1812, and zanamivir are also known as GS4071, RWJ-270201, and GG167, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Neuraminidases.

Purified B/Memphis/3/89 fast-growing influenza virus was treated with tosylsulfonyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone-trypsin followed by centrifugation to pellet the viral cores. The supernatant was then subjected to sucrose density gradient centrifugation and dialysis in order to obtain purified B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase heads (1). Neuraminidase heads from the reassortant virus A/NWS/33 × A/tern/Australia/G70c/75 (H1N9) were isolated and purified as reported by Laver et al. (19). The neuraminidase heads for B/Hong Kong/5/72, A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), and A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) influenza viruses were not isolated. Instead, enzyme assays using these viral strains utilized the neuraminidase activities present on the surface of the whole virus. Thus, MDCK-propagated virus was briefly centrifuged, and the supernatants, with appropriate dilution, were used directly in enzyme assays. Control assays established that the diluted cell culture media alone had no neuraminidase activity.

Inhibitors.

The synthesis of A-315675 will be described elsewhere (C. J. Maring et al., unpublished data). The details of the synthetic procedure can be obtained prior to publication by contacting the corresponding author. Zanamivir (GG167) was generously provided by the GlaxoSmithKline Co. Oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071) was synthesized according to the published procedure (17) from quinic acid. BCX-1812 was prepared as described by Babu et al. (2).

Cells and viruses.

Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) high glucose (Gibco BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (JRH Biosciences), 20 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco BRL), and the antibiotics penicillin G (100 units/ml) and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml) (Gibco BRL). Cells were routinely cultured in flasks or roller bottles at 37°C and 5% CO2.

The influenza virus strains B/Hong Kong/5/72 and A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The B/Memphis/3/89 fast-growing virus, A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) virus, and the A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) virus were obtained from the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (Memphis, Tenn.), Viral Antigens (Memphis, Tenn.), and the University of Virginia, respectively. Viral stocks for these five influenza virus strains were prepared as follows: roller bottles containing MDCK cells grown to a confluent state at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, 40 mM HEPES buffer, penicillin G (100 U/ml), and streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml) were inoculated with virus at a multiplicity of infection of approximately 0.1 PFU/cell. The roller bottles were maintained at 37°C until the cytopathogenic effect of the virus was complete, at which time the bottles were placed into a −80°C freezer in order to lyse the cells. The roller bottles were then thawed, and the contents were subjected to a low-speed centrifugation. The supernatants containing the viral stocks were stored at −80°C. The A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) virus used for neuraminidase enzyme assays was propagated in the allantoic sacs of fertilized hen eggs and purified by sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

The influenza B/Memphis/20/96 virus clinical isolate was kindly provided by Robert Webster of the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital and was passaged seven times in MDCK cells. The other influenza clinical isolates were obtained from the University of Virginia and were passaged between two and four times in MDCK cells.

Measurement of Ki values using a preincubation method.

Experiments to measure the Ki values for A-315675 and other test compounds were performed using a modification of an assay described previously (15). Test compounds at several concentrations were preincubated for 2 h with influenza neuraminidases from the various serotypes in neuraminidase assay buffer (20 mM N-ethylmorpholine, pH 7.5, buffer containing 10 mM CaCl2). The amount of neuraminidase used in the assays was predetermined so that the uninhibited control reactions yielded initial enzymatic velocities of 20 to 50 fluorescence units/min in the fluorogenic assay described below. Reactions were started by the addition of a small aliquot of 4-methylumbelliferyl-N-acetylneuraminic acid substrate (Sigma Chemical Co.) to yield a final concentration of 20 μM substrate (15 μM for B/Hong Kong/5/72 neuraminidase tests) in a final volume of 200 μl in white 96-well plates. Fluorescence measurements were obtained every 90 seconds for 2 h using a Fluoroskan II fluorescence plate reader (Titertek Instruments) equipped with excitation and emission filters of 355 ± 35 nm and 460 ± 25 nm, respectively. DeltaSoft II software (Biometallics) controlled the plate reader. Reaction velocities were calculated from the linear region of the progress curves. The Ki values were calculated by nonlinear regression curve fitting of the velocity data to the tight-binding inhibition equation 1 (24).

|

(1) |

where A = αVmax (S)/2[Km + (S)]; α is a factor to convert fluorescence units to molar concentration; Ki′ = Ki[1 + (S)/Km]; It = total inhibitor concentration; and Et = total active concentration of enzyme. The Km values for the various influenza neuraminidases with 4-methylumbelliferyl sialic acid substrate were measured from independent studies of the dependence of enzymatic velocities on substrate concentration. The Km values used to correct Ki′ to Ki values were 8.5, 8.9, 9.0, 15, 30, and 73 μM for B/Memphis/3/89, B/Hong Kong/5/72, A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1), and A/tern/Australia/G70c/75 (H1N9) neuraminidases, respectively.

Measurement of association (kon) and dissociation (koff) rate constants using the progress curve method.

The individual rate constants were measured using a modification of a previously described method (15). Reaction mixtures were placed in white, U-bottomed, 96-well plates and contained 20 μM 4-methylumbelliferyl sialic acid substrate in neuraminidase assay buffer and various concentrations of A-315675 or oseltamivir carboxylate at room temperature. Reactions were initiated by the addition of a small aliquot of either B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase heads or A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) whole virus into a final volume of 200 μl. The fluorescence increase resulting from the enzymatic reaction was monitored every 2 min for 2 to 4 h using the Fluoroskan II plate reader. The progress curve data were fit to equation 2 (7) using nonlinear regression and Kaleidagraph software.

|

(2) |

where Vo = initial velocity, Vs = final steady state velocity, kobs = first-order rate constant for the transition from initial to final velocity, and Fo and Ft represent the fluorescence values at time zero and time t, respectively. Replots of kobs versus inhibitor concentration were prepared, and the apparent kon and koff values were then calculated from the slope and intercept, respectively (7).

Measurement of dissociation rate constants using the dilution method.

B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase was preincubated for 2 h at room temperature in neuraminidase assay buffer only or with 200 nM of either A-315675 or oseltamivir carboxylate. These mixtures were then diluted 1,000-fold in neuraminidase assay buffer. Aliquots were removed immediately after dilution and periodically thereafter and assayed for neuraminidase enzymatic activity. Velocities from inhibitor-treated samples (Vi) were compared with the velocities from samples not treated with inhibitor (Vo) for each timepoint. The data were plotted as a function of time, and then the first-order rate constant for dissociation was measured by nonlinear regression to equation 3.

|

(3) |

The values for A and d were 1.0 and 0, respectively, for analysis of the oseltamivir carboxylate data. The A and d values were 0.9 and 0.1, respectively, for the analysis of the A-315675 data, which accounts for the expected 10% residual inhibition at the diluted concentration.

Plaque assays in MDCK cells.

The phenotypic susceptibility of influenza virus clinical isolates to neuraminidase inhibitors was determined using the plaque assay with confluent MDCK cell monolayers in the presence of the test compound and an agar overlay as previously described (11). Briefly, duplicate monolayers were inoculated with virus (25 to 60 PFU/well of a six-well plate) and were incubated at room temperature for 1 h with agitation. The virus inoculum was then discarded, and the cell monolayers were overlaid with DMEM supplemented with trypsin, agarose (0.6%), and the test compound. After 68 to 72 h of incubation at 34°C, the agar overlay was removed and the cell monolayers were stained with 0.1% crystal violet in 10% formaldehyde. The antiviral efficacy of the test compounds against the clinical isolates was assessed by measuring the diameter of the plaques at each drug concentration. The 50% effective concentration of the drug, i.e., that which reduced plaque size by 50% (EC50), was determined with the dose-effect analysis software from Biosoft (Cambridge, United Kingdom). All experiments were done in duplicate. The cytotoxicities of the test compounds were studied by exposing MDCK cells growing in log phase to test compounds for 4 days. The cytopathogenic effects were then quantitated using a slight modification of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide dye metabolism procedure described previously (16).

The effectiveness of the test compounds at reducing plaque number was also assessed using B/Hong Kong/5/72, B/Memphis/3/89 high grower, A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2), A/PR/8/34 (H1N1), and A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) influenza viruses. The protocol was similar to the plaque size reduction assay described above except that the viral inoculum contained 40 to 100 PFU/well and test compound, and it was not discarded before the agar overlay was applied. Cultures were incubated at 36°C for 3 to 5 days followed by treatment with 3.7% formalin in phosphate-buffered saline overnight. The agar overlay was removed, and the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet in distilled water. Plaques were counted manually from duplicate wells, and the compound concentration that reduced plaque number by 50% was calculated using linear regression.

RESULTS

Inhibition of influenza neuraminidases.

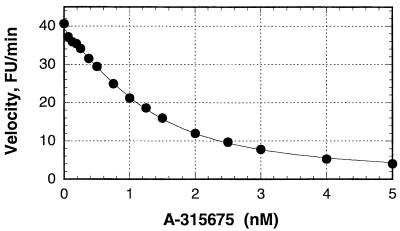

A-315675 and the other three compounds shown in Fig. 1 were evaluated as inhibitors of representative neuraminidases from three medically relevant influenza virus neuraminidase serotypes (A/N1, A/N2, and B) and an N9 serotype found in birds. Analysis of the inhibitory dose-response curves showed that all four compounds caused significant enzyme inhibition at low to subnanomolar concentrations. This observation raised the possibility that these compounds might be acting as reversible active-site titrants (24), causing inhibition at concentrations within a few times the concentration of enzyme used in the assay. This was a concern because 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) often underestimate the potency of active-site titrants, since no compound can achieve an IC50 lower than 50% of the concentration of enzyme in the assay. Therefore, we fit the dose-response curves to the tight-binding equation. This data analysis procedure enables the accurate measurement of dissociation equilibrium constants (Ki values) up to 100-fold lower than the concentration of enzyme used in the assay. A representative dose-response and curve fit to the tight-binding equation is shown in Fig. 2 using data corresponding to the inhibition of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase by A-315675. A concentration of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase active sites was estimated to be 1.3 nM in this experiment. This enzyme concentration brackets the range of A-315675 concentrations used in the experiment (0.06 to 5 nM) which justifies the use of the tight-binding equation to measure Ki. The apparent Ki of 0.47 nM was corrected by the factor 1 + (substrate concentration)/Km to obtain the true Ki of 0.14 nM. Thus, the difference between an IC50 and the true Ki can be substantial, as shown by the nearly 10-fold difference in values obtained in the experiment shown in Fig. 2. Table 1 shows a compilation of true Ki values measured in a similar way for the inhibition of various neuraminidases by the four test compounds.

FIG. 2.

Measurement of Ki for the inhibition of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase by A-315675. B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase heads and the indicated concentrations of A-315675 were preincubated for 2 h prior to initiating the reactions with substrate. The resulting initial velocities (closed circles) were fit to equation 1 using nonlinear regression as shown by the solid line. Note that the IC50 of A-315675 was 1.2 nM from this curve fit, yet the true Ki measured from this set of data and equation 1 was 0.14 nM. The concentration of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase active sites was estimated to be 1.3 nM from the curve fit. FU, fluorescence units.

TABLE 1.

A-315675 inhibits influenza neuraminidases from A and B strains

| Compound |

Ki (in nM)a for inhibition of neuraminidases derived from influenza virus strains

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/Hong Kong/5/72 | B/Memphis/3/89 | A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) | A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) | A/tern/Australia/G70c/75 (H1N9) | |

| A-315675 | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.073 ± 0.007 | 0.024 ± 0.004 |

| Oseltamivir carboxylate | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.05 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.10 ± 0.002 | 0.11 ± 0.007 | 0.11 ± 0.008 |

| BCX-1812 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 0.019 ± 0.001 | 0.014 ± 0.002 | 0.015 ± 0.011 |

| Zanamivir | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.086 ± 0.003 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.059 ± 0.003 | 0.11 ± 0.008 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

The Ki values reported in the the table are measurements of the dissociation equilibrium constants of the compounds with the influenza neuraminidases. These values were obtained from neuraminidase inhibition studies using at least 12 concentrations of inhibitor as described in the text. An example of this type of study is shown in Fig. 2. The numbers reported are the Ki ± the standard error of the measurement.

Analysis of the neuraminidase Ki values indicates that A-315675 is a potent, broad-spectrum inhibitor of neuraminidases derived from A/H1N1, A/H3N2, A/H1N9, and B strains of influenza virus (Table 1). A-315675 exhibited potency that was superior to that of oseltamivir carboxylate against the B and N2 neuraminidases and potency that was equivalent to that of oseltamivir carboxylate against the N1 neuraminidases. A-315675 also appeared to be somewhat superior to BCX-1812 against the B and N2 neuraminidases, although BCX-1812 was clearly more potent against the N1 enzymes. Zanamivir and A-315675 showed nearly equivalent potencies against the neuraminidases from the N1, N2, and B strains, but A-315675 was clearly more active than zanamivir against the N9 neuraminidase. With regard to the range of potencies across the three medically relevant neuraminidase serotypes (N1, N2, and B), A-315675 and zanamivir both showed a fairly narrow potency range of 4.5-fold. In contrast, the potency ranges for oseltamivir carboxylate and BCX-1812 were much wider, about 20- and 73-fold, respectively. The B/Hong Kong/5/72 neuraminidase was the least susceptible enzyme towards inhibition by A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate (Table 1). Likewise, the neuraminidases of N2 (from A/Tokyo/3/67) and N9 (from A/tern/Australia/G70c/75) subtypes were the least susceptible enzymes to the inhibition by BCX-1812 and zanamivir, respectively. If one judges the effectiveness of these neuraminidase inhibitors from the Ki values towards their least susceptible enzyme strains (Table 1), then A-315675 is roughly 6.5-fold more active than oseltamivir carboxylate, 3.5-fold more active than BCX-1812, and 4-fold more active than zanamivir.

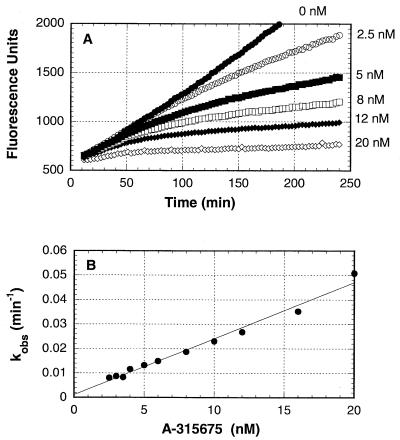

A-315675 dissociates more slowly from influenza neuraminidases than does oseltamivir carboxylate.

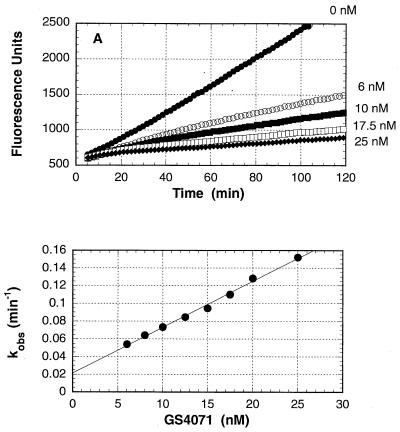

The progress curves shown in Fig. 3A indicate that the inhibition of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase by A-315675 was time dependent when the enzymatic reactions were started by the addition of neuraminidase. The observed first-order rate constants which describe the transition from initial to final steady-state velocities were measured for each concentration of A-315675 and plotted in Fig. 3B. The kon of 1.3 × 105 M−1 s−1 was calculated from the slope of the line in Fig. 3B after correction by the factor 1 + (substrate concentration)/Km. The koff of 1.9 × 10−5 s−1 was measured from the y axis intercept. A Ki of 0.15 nM was calculated from the ratio of these two rate constants. An experiment conducted in parallel with oseltamivir carboxylate is shown in Fig. 4A and 4B, and the rate constant results are reported in Table 2. The overall Ki values for A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate calculated from the progress curve data were in very close agreement with the Ki values measured independently using a 2-h preincubation method described above. This close correlation using the two methods provides an added measure of confidence to the accuracy of the kon and koff values reported in Table 2. Although the kon values for A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate differed by only 2.3-fold, the koff value for A-315675 was 18-fold lower than the value for oseltamivir carboxylate. The corresponding half times for dissociation of the compounds from B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase calculate to 10 h for A-315675, compared to only 33 min for oseltamivir carboxylate.

FIG. 3.

Time-dependent inhibition of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase by A-315675. (A) Reaction progress curves for the hydrolysis of 4-methylumbelliferyl sialic acid substrate by neuraminidase in the presence of the indicated concentrations of A-315675. Reactions were started by the addition of neuraminidase. (B) Dependence of the values for kobs on the concentration of A-315675. The solid line represents the best linear regression fit to a straight line. The apparent kon and koff rate constants were obtained from the slope and intercepts, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Time-dependent inhibition of B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase by oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071). (A) Reaction progress curves for the hydrolysis of 4-methylumbelliferyl sialic acid substrate by neuraminidase in the presence of the indicated concentrations of oseltamivir carboxylate. Reactions were started by the addition of neuraminidase. (B) Dependence of the values for kobs on the concentration of oseltamivir carboxylate. The solid line represents the best linear regression fit to a straight line. The apparent kon and koff rate constants were obtained from the slope and intercepts, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Rate and equilibrium constants for inhibition of influenza neuraminidases by A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071)

| Compound | Neuraminidase strain | Progress curve method

|

Preincubation/dilution methods

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kon (M−1 s−1) | koff (s−1) | Off-rate half-life (h) | Calculated Ki (in nM) | Measured Ki (in nM) | kon (M−1 s−1) | koff(s−1) | Off-rate half-life (h) | ||

| A-315675 | B/Memphis/3/89 | 1.3 × 105 | 1.9 × 10−5 | 10.1 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.4 × 105 | 2.0 × 10−5 | 9.7 |

| GS4071 | B/Memphis/3/89 | 2.9 × 105 | 3.5 × 10−4 | 0.55 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 × 105 | 2.4 × 10−4 | 0.79 |

| A-315675 | A/Tokyo/3/67 | 1.1 × 105 | 1.6 × 10−5 | 12.3 | 0.14 | 0.19 | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| GS4071 | A/Tokyo/3/67 | 2.7 × 105 | 1.9 × 10−4 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.3 | Not done | Not done | Not done |

A similar set of investigations was performed for the inhibition of A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) neuraminindase by A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate. The results reported in Table 2 indicate that A-315675 dissociates about 12-fold more slowly than does oseltamivir carboxylate from this enzyme, again with a half time for dissociation of many hours. Thus, A-315675 dissociates much more slowly than does oseltamivir carboxylate from both the A and B strains of influenza neuraminidase.

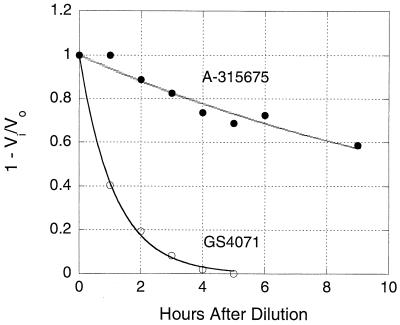

The results shown in Fig. 5 are from an experiment designed to directly measure the koff values using a dilution method. B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase was treated with saturating concentrations of A-315675 or oseltamivir carboxylate for 2 h, and then this mixture was diluted 1,000-fold to give a final concentration of compound that would yield 10% or less inhibition. Aliquots from this diluted mixture were removed periodically, assayed for enzymatic activity, and compared to uninhibited controls. The inhibition data were plotted as a function of time in Fig. 5 and fit to a first-order rate of decay to obtain the koff values of 0.0715 h−1 for A-315675 and 0.872 h−1 for oseltamivir carboxylate. These rate constants correspond to half times for dissociation from B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase of 9.7 h for A-315675 and 47.7 min for oseltamivir carboxylate. These values are in good agreement with those measured independently using the progress curve method described above and confirm the much lower rate of dissociation of A-315675 than for oseltamivir carboxylate.

FIG. 5.

Measurement of the koff rate constants using the dilution method. B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase was preincubated either with buffer or with saturating concentrations of A-315675 (•) or oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071) (○) for 2 h and was then diluted 1,000-fold into assay buffer. Samples were removed periodically after dilution and assayed for enzymatic activity. Vi and Vo are the enzymatic velocities of the inhibitor-treated and uninhibited control samples, respectively. The solid lines represent nonlinear regression fits to a first-order decay equation in order to measure the koff rate constants.

Anti-influenza activity of A-315675 in cell culture.

The anti-influenza activity of the neuraminidase inhibitors was determined against selected influenza A and B viruses which represent the three medically important major neuraminidase serotypes using a standard cell culture plaque reduction assay. The EC50 for each combination of compound and virus is shown in Table 3. These results indicate that A-315675 was three- to sevenfold more potent than oseltamivir carboxylate against all the influenza viruses tested in this panel. A-315675 appeared to be more potent than BCX-1812 against the B/Hong Kong/5/72 virus but two- to fourfold weaker against the two A/N1 strain viruses. The 35-fold range of EC50s for A-315675 is broader than the 4.5-fold Ki value range observed in the enzymatic assay (Table 1). Similar observations have been published for zanamivir (36) and oseltamivir carboxylate (22). This is not surprising because the EC50 for a particular virus is influenced by the properties of both the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase proteins (21). For a given panel of influenza viruses, one would expect a wider range of EC50s than of Ki values due to the additional differences of hemagglutinins within the panel. Thus, the antiviral activities are best interpreted by comparing the EC50s for the three inhibitors against the same viral strain, rather than comparing the EC50s between strains. It should be noted that MDCK cells replicating in log phase showed no signs of cytotoxicity when treated with A-315675 at compound concentrations as high as 200 μM or with oseltamivir carboxylate or BCX-1812 at compound concentrations as high as 100 μM.

TABLE 3.

A-315675 inhibits replication of influenza viruses in cell culture

| Compound | EC50s (in nM)a for inhibition of influenza virus replication

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B/Hong Kong/5/72 | B/Memphis/3/89 | A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) | A/PR/8/34 (H1N1) | A/Texas/36/91 (H1N1) | |

| A-315675 | 14.1 ± 3.1 | 6.7 ± 2.5 | 5.9 ± 3.1 | 0.4 ± 0.2 | 0.4 ± 0.3 |

| Oseltamivir carboxylate | 79 | 45 | 34 | 1.2 | 2.1 |

| BCX-1812 | 41 | 8.4 | 5.5 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

EC50s represent the concentration of compound necessary to reduce the plaque number by 50% relative to control wells that did not contain a test compound. The values reported for A-315675 antiviral activity represent the mean EC50 and standard deviation resulting from five experiments conducted on separate occasions. The values associated with the antiviral activities for oseltamivir carboxylate and BCX-1812 were from single determinations.

The antiviral activities of A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate were also tested against recent clinical isolates representing the H1N1, H3N2, and B serotypes in a plaque size reduction assay. The results shown in Table 4 indicate that both A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate were active against all the isolates tested. If one defines significantly greater potency as being manifested when the EC50 for one compound is more than threefold lower than the EC50 for its competitor, then A-315675 was more active than oseltamivir carboxylate against three (C23d, C31d,and C9d) of the eight H1N1 isolates. Similarly, oseltamivir carboxylate was more active than A-315675 against two H1N1 isolates (C23c and C9c) with the other isolates in this category exhibiting equivalent susceptibility to the two drugs. For the four H3N2 isolates, oseltamivir carboxylate was more active than A-315675 against one isolate (C32c), with the other three showing equivalent susceptibilities. A-315675 exhibited antiviral potencies that were more active than oseltamivir carboxylate against eight of the nine B strain influenza clinical isolates. The remaining B strain isolate (G72) exhibited equivalent susceptibilities to the two compounds.

TABLE 4.

Susceptibility of clinical isolates to neuraminidase inhibitors A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate (GS4071) in MDCK cells

| Isolate | Yr of isolation | Antigenicity | EC50 (μg/ml)a, b for:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-315675 | GS4071 | |||

| H1N1 | ||||

| C23c | 1991-1992 | A/Taiwan/01/86-like | ≤1.5 ± 1.5 | ≤0.045 ± 0.035 |

| C23d | 1991-1992 | A/Taiwan/01/86-like | 0.01 | 0.10 |

| C28c | 1994-1995 | A/Texas/36/91-like | ≤0.015 ± 0.005 | 0.01 ± 0.00 |

| C31c | 1995-1996 | A/Texas/36/91-like | ≤0.02 ± 0.01 | ≤0.03 ± 0.02 |

| C31d | 1995-1996 | A/Texas/36/91-like | ≤0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| C1d | 1983-1984 | Untyped | ≤0.025 ± 0.02 | ≤0.01 ± 0.00 |

| C9c | 1986-1987 | A/Singapore/6/86-like | 1.25 ± 0.75 | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| C9d | 1986-1987 | A/Singapore/6/86-like | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| H3N2 | ||||

| C25c | 1993-1994 | A/Beijing/32/92-like | ≤0.04 ± 0.03 | ≤0.015 ± 0.005 |

| C26c | 1994-1995 | A/Shangdong/09/93-like | 5.1 ± 4.9 | 5.1 ± 5.0 |

| C32c | 1995-1996 | A/Johannesburg/33/94-like | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.075 ± 0.025 |

| C34c | 1996-1997 | A/Wuhan/359/95-like | ≤0.03 ± 0.02 | ≤0.01 ± 0.00 |

| B | ||||

| C17c | 1990-1991 | Untyped | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.055 ± 0.005 |

| C29c | 1994-1995 | B/Beijing/184/93-like | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.045 ± 0.005 |

| C33d | 1995-1996 | B/Beijing/184/93-like | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.045 ± 0.005 |

| C35c | 1996-1997 | B/Beijing/184/93-like | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.055 ± 0.005 |

| B/Memphis/20/96 | 1996 | B/Beijing/184/93-like | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.055 ± 0.005 |

| G26 | 1998-1999 | Untyped | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.05 ± 0.00 |

| G42 | 1998-1999 | Untyped | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.125 ± 0.075 |

| G62 | 1998-1999 | Untyped | <0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.04 ± 0.01 |

| G72 | 1998-1999 | Untyped | <0.01 ± 0.00 | ≤0.01 ± 0.00 |

EC50 represents the concentration of test compound that results in a 50% reduction of plaque size. The reported values represent the mean and standard deviation from two measurements, except for C23d, which was tested only once. In cases where an individual EC50 was < 0.01 μg/ml, the mean and standard deviation were calculated using a value of 0.01 μg/ml with the reported EC50 in the table having the symbol “≤” as a prefix. The “<” prefix indicates that both replicates yielded EC50 values that were < 0.01 μg/ml.

The average plaque size for the untreated controls for the individual isolates ranged from 1.0 to 1.8 mm, and the standard deviations ranged from 0.1 to 0.6 mm.

DISCUSSION

A-315675 is a highly optimized, pyrrolidine-based influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor, as demonstrated by the Ki values reported in Table 1. Indeed, the potency of A-315675 against the B/Memphis/3/89 neuraminidase represents a 107-fold improvement in binding affinity relative to the original pyrrolidine screening hit that started our influenza neuraminidase inhibitor program (16). Although influenza neuraminidase inhibitor potencies are often reported as IC50s (2, 3, 22), we have elected to measure potencies as Ki values. Ki values reflect true binding affinity, whereas IC50s for competitive inhibitors are influenced by substrate concentrations (4) and, in cases where potent enzyme inhibitors are evaluated, the enzyme concentrations used in the assays (24, 35). For competitive inhibitors, Ki values are always lower than IC50s, which likely explains why the Ki values measured in this study are, on average, 7.5-fold lower than the IC50s reported in the literature for oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir (3, 22) when comparable experiments are examined. The Ki values reported here thus represent the most comprehensive study of true binding affinities for the four most potent influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitors studied to date. Overall, A-315675 exhibited potencies that were comparable to, or in some cases, superior to those of the three other compounds against all influenza neuraminidase subtypes tested, except for the two N1 enzymes that appeared to be very sensitive to BCX-1812. This favorable overall comparison with clinically effective agents leads us to conclude that A-315675 possesses sufficient binding affinity towards the various influenza virus neuraminidase subtypes to warrant further investigation as an anti-influenza drug.

This study established that A-315675 is a time-dependent inhibitor of B/Memphis/3/89 and A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) influenza virus neuraminidases. Time-dependent inhibition, sometimes referred to as slow-binding inhibition (23), has also been described for the potent neuraminidase inhibitors zanamivir (9), oseltamivir carboxylate (15, 31), and BCX-1812 (E. Z. Baum, K. Andries, R. Willbrords, L. Ly, and K. Bush, Antivir. Res. 46:A58, abstr. 74, 2000). The X-ray crystal structure of A-315675 bound to N9 neuraminidase shows that no obvious changes occur to the protein or inhibitor upon binding, except for a small conformational change in the Glu 278 side chain (Maring et al., unpublished). However, this Glu 278 side-chain conformational change also occurs with the original pyrrolidine screening hit (16), but this screening hit does not show time-dependent inhibition. Thus, this small conformational change is not likely to be the mechanism responsible for the time-dependent inhibition phenomenon. It has been suggested that the time-dependent inhibition observed for oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir arises from the low rates of dissociation of these compounds from influenza neuraminidases (15). Studies to measure the koff values of A-315675 from B/Memphis/3/89 and A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) influenza virus neuraminidases establish the koff to be 1.6 × 10−5 to 2.0 × 10−5 s−1 (Table 2). As previously reported (15), any compound with a koff of 3 × 10−4 s−1 or less will show the time-dependent inhibition phenomenon when tested at concentrations within 10-fold of its Ki. Thus, the time-dependent inhibition of influenza virus neuraminidases observed for A-315675 likely arises only because the compound dissociates very slowly from the enzyme.

It is interesting that the koff values for A-315675 are 12- to 18-fold lower than the koff rate measured for oseltamivir carboxylate under identical conditions. The koff values of 2 × 10−4 to 3 × 10−4 s−1 for oseltamivir carboxylate reported in this study at pH 7.5 are similar to the values measured previously with B/Memphis/3/89 and A/Tokyo/3/67 (H3N2) neuraminidase heads at pH 6.0 (15). koff values of roughly 2 × 10−4 s−1 have also been reported for zanamivir against influenza A and B strain neuraminidases (9), and so zanamivir and oseltamivir carboxylate appear to have koff values of similar magnitude. The corresponding half times for dissociation of these compounds from neuraminidases calculate to 10 to 12 h for A-315675 but only 0.55 to 1 h for oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir. This large difference in half times for dissociation may have some therapeutic implications. For example, A-315675 might exert a prolonged duration of action relative to oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir under conditions when bulk drug has been removed from the site of the viral infection. If a postantibiotic effect (6) were to be observed with A-315675, then this property might translate into less frequent dosing for A-315675 than for oseltamivir carboxylate and zanamivir, both of which are dosed twice per day. It should be noted that the kon values for both A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate are sufficiently high so that both compounds should bind to neuraminidase within seconds when the compounds are present at concentrations above 0.1 μg/ml. Lastly, the narrow range of Ki values for A-315675 across the various neuraminidase subtypes makes it likely that the koff values will also not vary by more than a few times. Thus, the very great half time for dissociation of A-315675, and any therapeutic benefits derived from it, will likely apply to the inhibition and treatment of a broad range of influenza virus neuraminidase subtypes.

The trends that were observed in the neuraminidase inhibition assay were also apparent when the compounds were tested for anti-influenza activity in cell culture. Specifically, A-315675 exhibited potencies comparable or superior to those of oseltamivir carboxylate and BCX-1812 against a panel of laboratory strain viruses, although BCX-1812 may be slightly more active against the N1 viruses (Table 3). A more extensive evaluation of A-315675 and oseltamivir carboxylate against a panel of recent influenza virus clinical isolates suggested that the two compounds were roughly comparable in potencies toward influenza viruses containing the N1 and N2 neuraminidase subtypes but that B strain viruses were significantly more susceptible to A-315675 (Table 4). This latter finding is consistent with the superior potency of A-315675 relative to that of oseltamivir carboxylate against influenza B strain laboratory viruses in cell culture as well as against B strain neuraminidases in enzyme assays. The combined cell culture results establish A-315675 as a compound with potent anti-influenza properties in cell culture.

In summary, we have presented evidence to establish that A-315675 is a potent inhibitor of both A and B strain influenza virus neuraminidases and an effective, broad-spectrum anti-influenza agent in cell culture. A-315675 exhibits potencies that are clearly superior to those of oseltamivir carboxylate against B strain neuraminidases in enzyme assays. This property was also shown to translate to clear superiority of A-315675 versus oseltamivir carboxylate in cell culture assays against both laboratory- and clinic-isolated B strain influenza viruses. The favorable enzyme potencies, low rate of dissociation, and antiviral results relative to those for oseltamivir carboxylate and other clinically effective agents provide strong support for the further investigation of A-315675 as a potential therapy for influenza virus infections.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge A. Chris Krueger and Darold Madigan for the synthesis of BCX-1812 and the entire antiviral chemistry team for the synthesis of A-315675. We are also grateful to W. Graeme Laver of the Australian National University for the gift of several neuraminidase subtypes. Lastly, we thank Shing Chang and Dan Norbeck for their support of our influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Air, G. M., W. G. Laver, M. Luo, S. J. Stray, G. Legrone, and R. G. Webster. 1990. Antigenic, sequence and crystal variation in influenza B neuraminidase. Virology 177:578-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babu, Y. S., P. Chand, S. Bantia, P. Kotian, A. Dehghani, Y. El-Kattan, T.-H. Lin, T. L. Hutchison, A. J. Elliott, C. D. Parker, S. L. Ananth, L. L. Horn, G. W. Laver, and J. A. Montgomery. 2000. BCX-1812 (RWJ-270201): discovery of a novel, highly potent, orally active, and selective influenza neuraminidase inhibitor through structure-based drug design. J. Med. Chem. 43:3482-3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bantia, S., C. D. Parker, S. L. Ananth, L. L. Horn, K. Andries, P. Chand, P. L. Kotian, A. Dehghani, Y. El-Kattan, T. Lin, T. L. Hutchison, J. A. Montgomery, D. L. Kellog, and Y. S. Babu. 2001. Comparison of the anti-influenza virus activity of RWJ-270201 with those of oseltamivir and zanamivir. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1162-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng, Y.-C., and W. H. Prusoff. 1973. Relationship between the inhibition constant, Ki, and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 22:3099-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couch, R. B. 1993. Advances in influenza virus vaccine research. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 685:803-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Craig, W. A. 1993. Post-antibiotic effects in experimental infection models: relationship to in-vitro phenomena and to treatment of infections in man. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 31(Suppl. D):149-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duggleby, R. G., P. V. Attwood, J. C. Wallace, and D. B. Keech. 1982. Avidin is a slow-binding inhibitor of pyruvate carboxylase. Biochemistry 21:3364-3370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glezen, W. P. 1982. Serious morbidity and mortality associated with influenza epidemics. Epidemiol. Rev. 4:25-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart, G. J., and R. C. Bethell. 1995. 2,3-Didehydro-2,4-dideoxy-4-guanidino-N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid is a slow-binding inhibitor of sialidase from both influenza A virus and influenza B virus. Mol. Biol. Int. 36:695-703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayden, F. G., R. B. Belshe, R. D. Clover, A. J. Hay, M. G. Oakes, and W. Soo. 1989. Emergence and apparent transmission of rimantidine-resistent influenza A virus in families. New Engl. J. Med. 321:1696-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayden, F. G., K. M. Cote, and R. G. Douglas, Jr. 1980. Plaque inhibition assay for drug susceptibility testing of influenza viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 17:865-870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayden, F. G., and A. J. Hay. 1992. Emergence and transmission of influenza A viruses resistant to amantadine and rimantidine. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 176:119-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayden, F. G., A. D. M. E Osterhaus, J. Treanor, D. M. Fleming, G. Y. Aoki, K. G. Nicholson, A. M. Bohnen, H. M. Hirst, O. Keene, and K. Wightman. 1997. Efficacy and safety of the neuraminidase inhibitor zanamivir in the treatment of influenza virus infections. New Engl. J. Med. 337:874-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayden, F. G., J. J. Treanor, R. S. Fritz, M. Lobo, R. F. Betts, M. Miller, N. Kinnersley, R. G. Mills, P. Ward, and S. E. Straus. 1999. Use of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in experimental human influenza. JAMA 282:1240-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kati, W. M., A. S. Saldivar, F. Mohamadi, H. L. Sham, W. G. Laver, and W. E. Kohlbrenner. 1998. GS4071 is a slow-binding inhibitor of influenza neuraminidase from both A and B strains. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 244:408-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kati, W. M., D. Montgomery, C. Maring, V. S. Stoll, V. Giranda, X. Chen, W. G. Laver, W. Kohlbrenner, and D. W. Norbeck. 2001. Novel α- and β-amino acid inhibitors of influenza virus neuraminidase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2563-2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim, C. U., W. Lew, M. A. Williams, H. Liu, L. Zhang, S. Swaminathan, N. Bischofberger, M. S. Chen, D. B. Mendel, C. Y. Tai, W. G. Laver, and R. C. Stevens. 1997. Influenza neuraminidase inhibitors possessing a novel hydrophobic interaction in the enzyme active site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119:681-690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klenk, H.-D., and R. Rott. 1988. The molecular biology of influenza virus pathogenicity. Adv. Virus Res. 34:247-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laver, W. G., P. M. Colman, R. G. Webster, V. S. Hinshaw, and G. M. Air. 1984. Influenza virus neuraminidase with haemagglutinin activity. Virology 137:314-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKimm-Breschkin, J. L. 2000. Resistance of influenza viruses to neuraminidase inhibitors—a review. Antivir. Res. 47:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKimm-Breschkin, J. L., T. J. Blick, A. Sahasrabudhe, T. Tiong, D. Marshall, G. J. Hart, R. C. Bethell, and C. R. Penn. 1996. Generation and characterization of variants of NWS/G70c influenza virus after in vitro passage in 4-amino-Neu5Ac2en and 4-guanidino-Neu-5Ac2en. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:40-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendel, D. B., C. Y. Tai, P. A. Escarpe, W. Li, R. W. Sidwell, J. H. Huffman, C. Sweet, K. J. Jakeman, J. Merson, S. A. Lacy, W. Lew, M. A. Williams, L. Zhang, M. S. Chen, N. Bischofberger, and C. U. Kim. 1998. Oral administration of a prodrug of the influenza virus neuraminidase inhibitor GS4071 protects mice and ferrets against influenza infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:640-646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison, J. F. 1982. The slow-binding and slow, tight-binding inhibition of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 7:102-105. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison, J. F., and S. R. Stone. 1985. Approaches to the study and analysis of the inhibition of enzymes by slow- and tight-binding inhibitors. Comments Mol. Cell. Biophys. 2:347-368. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palese, P., K, Tobita, M. Ueda, and R. W. Compans. 1974. Characterization of temperature sensitive influenza virus mutants defective in neuraminidase. Virology 61:397-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palese, P., and R. W. Compans. 1976. Inhibition of influenza virus replication in tissue culture by 2-deoxy-2,3-dehydro-N-trifluoroacetylneuraminic acid (FANA): mechanism of action. J. Gen. Virol. 33:159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Powers, D. C. 1996. Influenza virus vaccines. Drugs Today 3:225-237. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sidwell, R. W., D. F. Smee, J. H. Huffman, D. L. Barnard, K. W. Bailey, J. D. Morrey, and Y. S. Babu. 2001. In vivo influenza virus inhibitory effects of the cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitor RWJ-270201. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:749-757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silagy, C. A., and the MIST Study Group. 1998. Randomised trial of efficacy and safety of inhaled zanamivir in treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. Lancet 352:1877-1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smee, D. F., J. H. Huffman, A. C. Morrison, D. L. Barnard, and R. W. Sidwell. 2001. Cyclopentane neuraminidase inhibitors with potent in vitro anti-influenza virus activities. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:743-748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tai, C. Y., P. A. Escarpe, R. W. Sidwell, M. A. Williams, W. Lew, H. Wu, C. U. Kim, and D. B. Mendel. 1998. Characterization of human influenza virus variants selected in vitro in the presence of the neuraminidase inhibitor GS4071. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:3234-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treanor, J. J., F. G. Hayden, P. S. Vrooman, R. Barbarash, R. Bettis, D. Riff, S. Singh, N. Kinnersley, P. Ward, and R. G. Mills. 2000. Efficacy and safety of the oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir in treating acute influenza. JAMA 283:1016-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.von Itzstein, M., W.-Y. Wu, G. B. Kok, M. S. Pegg, J. C. Dyason, B. Jin, T. V. Phan, M. L. Smythe, H. F. White, S. W. Oliver, P. M. Colman, J. N. Varghese, D. M. Ryan, J. M. Woods, R. C. Bethell, V. J. Hotham, J. M. Cameron, and C. R. Penn. 1993. Rational design of potent sialidase-based inhibitors of influenza virus replication. Nature 363:418-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, G. T., Y. Chen, S. Wang, R. Gentles, T. Sowin, W. Kati, S. Muchmore, V. Giranda, K. Stewart, H. Sham, D. Kempf, and W. G. Laver. 2001. Design, synthesis, and structural analysis of influenza neuraminidase inhibitors containing pyrrolidine cores. J. Med. Chem. 44:1192-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams, J. W., and J. F. Morrison. 1979. The kinetics of reversible tight-binding inhibition. Methods Enzymol. 63:437-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods, J. M., R. C. Bethell, J. A. V. Coates, N. Healy, S. A. Hiscox, B. A. Pearson, D. M. Ryan, J. Ticehurst, J. Tilling, S. M. Walcott, and C. R. Penn. 1994. 4-Guanidino-2,4-dideoxy-2,3-dehydro-N-acetylneuraminic acid is a highly effective inhibitor both of the sialidase (neuraminidase) and of growth of a wide range of influenza A and B viruses in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:1473-1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]