Abstract

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (InsP3Rs) were recently demonstrated to be activated independently of InsP3 by a family of calmodulin (CaM)-like neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins (CaBPs). We investigated the interaction of both naturally occurring long and short CaBP1 isoforms with InsP3Rs, and their functional effects on InsP3R-evoked Ca2+ signals. Using several experimental paradigms, including transient expression in COS cells, acute injection of recombinant protein into Xenopus oocytes and 45Ca2+ flux from permeabilised COS cells, we demonstrated that CaBPs decrease the sensitivity of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release (IICR). In addition, we found a Ca2+-independent interaction between CaBP1 and the NH2-terminal 159 amino acids of the type 1 InsP3R. This interaction resulted in decreased InsP3 binding to the receptor reminiscent of that observed for CaM. Unlike CaM, however, CaBPs do not inhibit ryanodine receptors, have a higher affinity for InsP3Rs and more potently inhibited IICR. We also show that phosphorylation of CaBP1 at a casein kinase 2 consensus site regulates its inhibition of IICR. Our data suggest that CaBPs are endogenous regulators of InsP3Rs tuning the sensitivity of cells to InsP3.

Keywords: Ca2+ , CaBP, InsP3 , signalling

Introduction

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ control a diverse array of cellular processes, including fertilisation, memory formation and gene transcription (Berridge et al, 2003). Increases in cytosolic Ca2+ levels may arise as a result of either its release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) intracellular Ca2+ store or influx across the plasma membrane. The principal Ca2+ release channels on the ER belong to the ryanodine receptor (RyR) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (InsP3R) families (Ehrlich, 1995; Iino, 1999).

Both families of channels are biphasically regulated by Ca2+ (Bezprozvanny et al, 1991). In addition, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) is a co-agonist for InsP3Rs (Bezprozvanny et al, 1991). The mechanism by which Ca2+ exerts its effect has been the subject of intense investigation resulting in the identification of several Ca2+ binding sites in the InsP3R (Sienaert et al, 1997). In addition to a direct action of Ca2+ on the receptor, Ca2+ may function through Ca2+-sensing proteins that either bind directly to or modify channel activity by the addition/removal of secondary modifications such as phosphate groups (Patel et al, 1999; Thrower et al, 2001; Nadif Kasri et al, 2002; Taylor and Laude, 2002; Roderick and Bootman, 2003). The tetra EF-hand-containing Ca2+ sensor protein calmodulin (CaM) has been shown to modulate the activity of InsP3Rs in both a Ca2+-dependent and -independent manner (Reviewed in Nadif Kasri et al, 2002; Taylor and Laude, 2002). The Ca2+-independent CaM binding domain has been mapped to two noncontiguous sites in the NH2-terminal 159 amino acids (aa) of the type 1 InsP3R (InsP3R1) (Sienaert et al, 2002). The interaction of CaM with these sites was shown to decrease the affinity of the receptor for InsP3 (Sienaert et al, 2002). The inhibition of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release (IICR) by CaM-like proteins may have great significance in neurons where it has been shown to underlie processes including axonal guidance, growth cone formation as well as excitability, which govern long-term potentiation and depression (LTD) associated with memory formation (Nakamura et al, 1999; Nagase et al, 2003). The propagation of Ca2+ release following repetitive stimulation of the parallel fibre/Purkinje cell synapses is generally restricted to the postsynaptic spines. This is surprising, since Purkinje cells abundantly express InsP3Rs throughout the cell (Snyder and Supattapone, 1989; Volpe et al, 1991). Thus, it has been proposed that the high levels of CaM also present in these cells (∼10 μM; Kakiuchi et al, 1982) decrease IICR and restrict excitability (Cardy and Taylor, 1998).

A family of neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins (CaBPs), sharing significant homology in sequence and structure with CaM, has recently been described in the retina and brain (Haeseleer et al, 2000). This family of proteins belongs to the superfamily of neuronal Ca2+ sensor proteins that also include NCS1 (or frequenin) and KChiPs, which have been shown to be involved in neuronal signalling (Burgoyne and Weiss, 2001). Unlike CaM, one or two of the EF hand Ca2+-binding domains in CaBPs are nonfunctional (Haeseleer et al, 2000). CaBPs have been shown to bind to the NH2-terminus of InsP3Rs in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Furthermore, it was reported that CaBP1 activated Ca2+ release through InsP3Rs independent of InsP3 binding (Yang et al, 2002). Thus, if CaBPs act as endogenous surrogates for InsP3, it is possible that InsP3Rs may be directly regulated by Ca2+, allowing them to act as true Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release channels in a manner similar to RyRs (Bootman et al, 2002).

In this study, we rigorously tested the functional relationship between CaBP- and InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release. We determined that CaBP1 interacted with InsP3Rs in a Ca2+-independent manner. This interaction was localised to a peptide sequence in the NH2-terminal 159 aa of InsP3R1 to which CaM has also been shown to bind. CaBP1 binding resulted in a decrease in the sensitivity of IICR. This was demonstrated by measuring IICR in COS cells overexpressing CaBP1, in Xenopus oocytes microinjected with recombinant CaBP1 and permeabilised COS cells exposed to recombinant CaBP1. In addition, CaBP1 by itself could not activate Ca2+ release. We also show that CaBP1 is phosphorylated at a casein kinase 2 consensus sequence, which regulates its efficacy to inhibit IICR. The use of COS cells and Xenopus oocytes, which do not express endogenous CaBP1, provided an ideal null background to investigate the function of CaBP1. Our data suggest that CaBP1 can behave as an endogenous regulator of InsP3R activity, and may serve to tune the sensitivity of InsP3Rs to InsP3. Although structurally similar to CaM, CaBPs have distinct effects and provide an additional facet of InsP3R regulation.

Results

CaBP1 inhibits agonist-induced Ca2+ signals

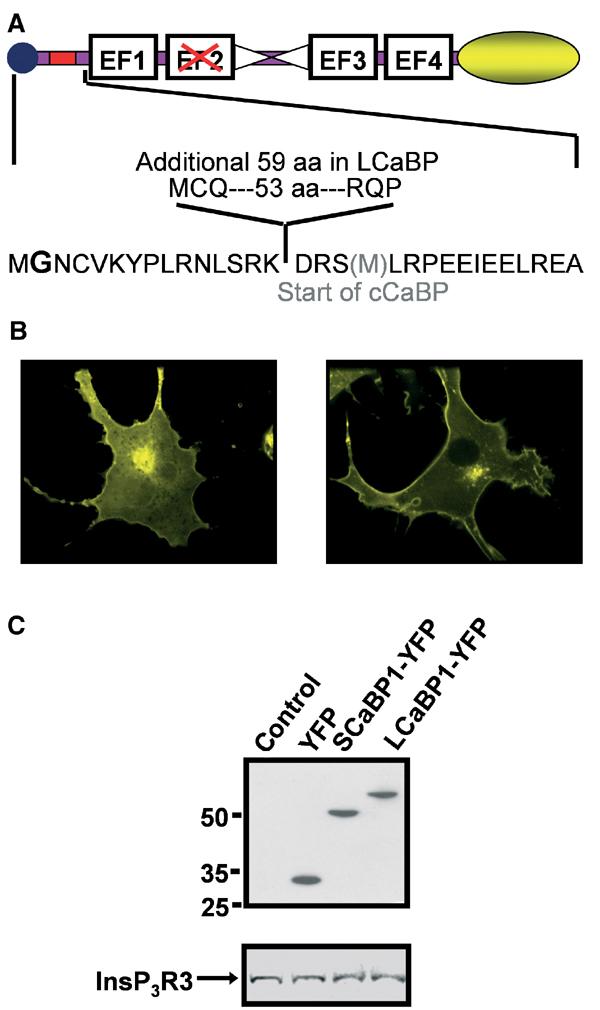

CaBP1 has previously been reported to increase the open probability of InsP3R independently of InsP3 in nuclei isolated from Xenopus oocytes (Yang et al, 2002). To test whether this was also true in an intact cellular system, we first adopted a heterologous expression approach. Expression vectors for both the naturally occurring long and short CaBP1 isoforms were generated. In addition, to identify cells expressing these constructs, YFP was appended to the COOH-terminus of the CaBPs (Figure 1A). Figure 1B shows that when overexpressed, both SCaBP1-YFP and LCaBP1-YFP are targeted primarily to the plasma membrane, with some of the protein also residing on intracellular membranes, including the Golgi apparatus. A weaker, but significant, fluorescence was also observed in the cytosol. Transiently expressed SCaBP1-YFP and LCaBP1-YFP, detected using an anti-GFP antibody, migrated at the expected molecular mass (Figure 1C, top panel). Equivalent levels of expression of the endogenous type 3 InsP3R (InsP3R3) were detected (the major InsP3R isoform in COS-7 cells; Wojcikiewicz, 1995) in lysates from FACS-isolated CaBP1-expressing cells, indicating that CaBP1 expression did not impact on the levels of endogenous InsP3Rs (Figure 1C, bottom panel).

Figure 1.

Design and expression of CaBP-YFP vectors. (A) Graphical representation of the LCaBP1-YFP and SCaBP1-YFP constructs used. The location of the additional aa in LCaBP1 compared to SCaBP1 is indicated by the red box. The central α-helix is indicated by the two triangles and the myristoylation sequence is represented by a circle. The four EF hand Ca2+-binding domains are indicated and the nonfunctional EF hand is shown by the red cross. The yellow ellipse illustrates the COOH-terminal YFP. In the lower panel, aa boundaries for both S/LCaBP and truncated cCaBP (additional methionine at the start of cCaBP shown in grey) are shown. The myristoylated glycine is in bold. (B) COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with S/LCaBP-YFP constructs. At 48 h post–transfection, cells were imaged confocally through a × 100, 1.4 n.a. oil immersion objective (Perkin-Elmer, Cambridge UK). The 488 nm line of the krypton/argon laser was used for excitation and emission collected >505 nm. (C) (Upper panel) Mobility of YFP, SCaBP1-YFP and LCaBP1-YFP was determined in transiently transfected COS-7 cells by Western blot using anti-GFP antibody. (Lower panel) Abundance of InsP3R3 was determined in cells transfected with YFP, SCaBP1, and LCaBP1 isolated by FACS.

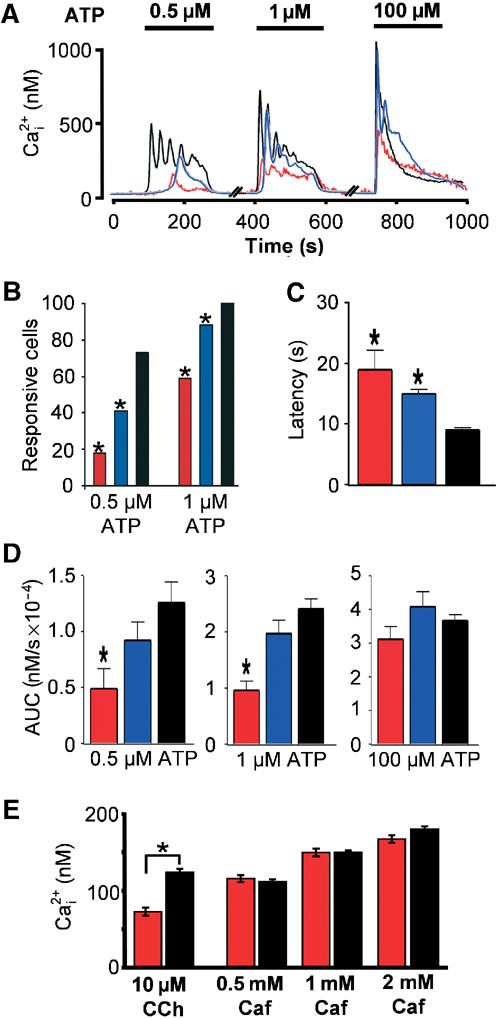

At 48 h post-transfection, ATP-evoked Ca2+ transients were monitored in Fura-2-loaded cells. Expression of either LCaBP1 or SCaBP1 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of responsive cells at both 0.5 and 1 μM ATP, and a decrease in the occurrence of agonist-evoked oscillations in those cells that responded (Figure 2A and B). In addition, the integrated Ca2+ response at these agonist concentrations was reduced (Figure 2D). The integrated Ca2+ response to maximal agonist (100 μM ATP) was not significantly affected by CaBP1 expression, indicating that the Ca2+ content of the agonist-sensitive store was unchanged (Figure 2D). Although the amplitude and integrated Ca2+ response to maximal ATP were not altered by CaBP expression, the latency between agonist addition and the peak response was significantly prolonged. Therefore, even in the face of maximal InsP3 increases, CaBP effected a delay in the development of the Ca2+ transient, consistent with a decrease in the sensitivity of InsP3Rs (Figure 2C). Similar results were obtained when SCaBP1 was expressed in HeLa, SH-SY5Y and HEK293 cells, indicating that CaBP1 could act on IICR from a variety of cell types expressing differing InsP3R isoform complements (data not shown). No effect on IICR was observed following expression of EYFP alone (data not shown). Since both LCaBP1 and SCaBP1 were inhibitory to Ca2+ release, an NH2-terminally truncated cDNA construct spanning the conserved regions of these two isoforms (cCaBP) was expressed (Figure 1A). cCaBP resulted in a significant decrease in the percentage of responding cells at 0.5 μM ATP from 63.9±2.9% in control cells to 26.4±3.7% in cCaBP-expressing cells (n=11, P<0.05), which is comparable to that observed for long and short CaBP (Figure 2B). The specificity of the effect of CaBP1 upon IICR was further demonstrated by the absence of any inhibition of caffeine-induced Ca2+ release through RyRs in HEK293 cells in which they are stably expressed (Rossi et al, 2002) (Figure 2E). Carbachol-induced Ca2+ release measured in the same cells overexpressing CaBP1 was however inhibited, suggesting that InsP3Rs were specifically targeted.

Figure 2.

CaBP1 inhibits agonist-induced Ca2+ release. Responses to the InsP3-generating agonist ATP were examined in COS-7 cells transfected with either SCaBP1 (red trace and bars) or LCaBP1 (blue trace and bars), respectively. (A) Responses from transfected and nontransfected (control, black trace) cells were recorded from the same field of view. The traces depict responses from individual cells. The concentrations of ATP used are shown by the solid bars above the traces. (B) Quantitative analysis of the experiments depicted in (A). (C) Latency between the application of agonist and the peak Ca2+ response in cells stimulated with 100 μM ATP. (D) Integrated Ca2+ signal observed with 0.5, 1 and 100 μM ATP. (E) Caffeine-induced Ca2+ release in HEK293 cells stably expressing RyR3 transiently transfected with SCaBP1-YFP. The inhibition of IICR in CaBP-expressing cells was confirmed by application of the InsP3-generating agonist carbachol (10 μM CCH, red bar). The peak amplitudes of the Ca2+ transients for control (black bars) and SCaBP1-YFP (red bars) induced by each caffeine concentration applied are indicated in the bar graph. Statistical significance is denoted by an asterisk.

To rule out that the effect of CaBP1 on IICR was mediated by Ca2+ buffering, the EF-hand-containing Ca2+ buffer protein calbindin was overexpressed and its effects on Ca2+ signals were examined. Unlike CaBP, calbindin overexpression did not significantly reduce the number of cells responding to ATP, even at the lowest agonist concentrations used (Supplementary Figure 1). Furthermore, overexpression of CaBP1 in which the three EF hands were disabled (CaBP1134) (Yang et al, 2002) resulted in a similar level of inhibition of IICR as cells expressing wild-type CaBP1 (13±6% of cells expressing CaBP134 versus 17.6±4.5% of cells for SCaBP1 responded to 0.5 μM ATP, P>0.05). Thus, we conclude that the inhibition of IICR by CaBP1 is Ca2+ independent.

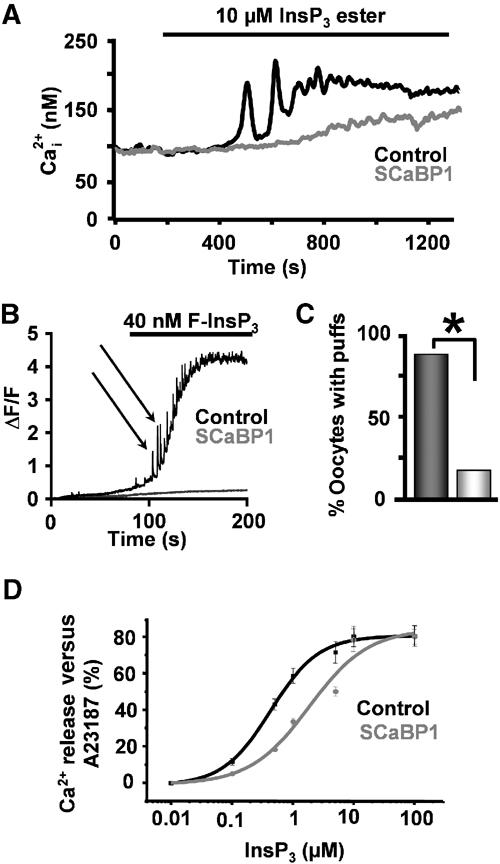

CaBP1 directly targets InsP3Rs to inhibit IICR

To test that the inhibition of IICR was due to a direct effect on InsP3Rs, we employed a number of strategies. Application of a cell-permeant InsP3 ester (InsP3BM) (Thomas et al, 2000) induced a robust Ca2+ transient preceded by Ca2+ oscillations in control COS-7 cells, which was not observed in CaBP1-overexpressing cells (Figure 3A). Confocal microscopy was also used to monitor the effect of CaBP on IICR in Fluo-4-loaded Xenopus oocytes. The oocytes were injected with either recombinant CaBP1 (8.5 μM final) or vehicle 30 min prior to imaging. In control oocytes, injection of 40 nM F-InsP3 resulted in an accumulating increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels punctuated by Ca2+ puffs (Figure 3B), which was not observed in the majority of oocytes injected with CaBP1 (Figure 3C). At 100 nM F-InsP3, however, Ca2+ release was observed in CaBP1-injected oocytes, although puffs prior to the Ca2+ tide were not apparent (data not shown). Furthermore, no calcium release was observed in oocytes imaged simultaneously with injection of recombinant CaBP1 alone (Supplementary Figure 2). These data indicated that CaBP1 did not induce Ca2+ release, did not irreversibly inhibit InsP3Rs, but significantly reduced the sensitivity of IICR.

Figure 3.

CaBP1 inhibits Ca2+ release induced by direct application of InsP3. (A) Ca2+ release following application of 10 μM cell-permeant InsP3 (InsP3BM) observed in control (black trace) and CaBP1-transfected (grey trace) COS-7 cells. (B, C) F-InsP3-induced Ca2+ release in control oocytes (black trace) and oocytes preinjected with 8.5 μM recombinant CaBP1 (grey trace). The black arrows in (B) indicate Ca2+ puffs. Oocytes were imaged as described in Materials and methods. (D) Effect of CaBP1 on InsP3-induced efflux of 45Ca2+ from COS cells. After loading permeabilised COS-1 cells for 45 min in 150 nM 45Ca2+, efflux was started in a medium containing 1 μM free Ca2+, with (circles) or without (squares) 10 μM SCaBP1. After 10 min of efflux, cells were challenged with InsP3 for 2 min. The increase in fractional loss provoked by the InsP3 challenge was plotted as a function of the applied InsP3 concentration. The Ca2+ release was normalized to the total releasable fraction by 5 μM A23187, which was taken as 100%. The results represent the mean±s.e.m. of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

In previous studies we have shown the affinity of the Ca2+-independent CaM binding site on InsP3R1 to be 2 μM (Sienaert et al, 2002). In this study, based on the amount of excess peptide required to prevent migration of CaBP into gels (depicted in Figure 4C) compared to CaM under the same conditions, we conclude that CaBP has a three-fold greater affinity for the InsP3R than CaM. Thus, to investigate the effects of CaBP on Ca2+ release, we used concentrations of the protein up to one order of magnitude greater than its Kd. To quantitate specifically the unidirectional flux of Ca2+, we measured InsP3-induced 45Ca2+ flux from permeabilised COS cells in the presence and absence of 10 μM His-tagged CaBP1. We found that CaBP1 significantly increased the IC50 of IICR from 0.41±0.13 to 1.83±0.21 μM (P<0.005) (Figure 3D).

Figure 4.

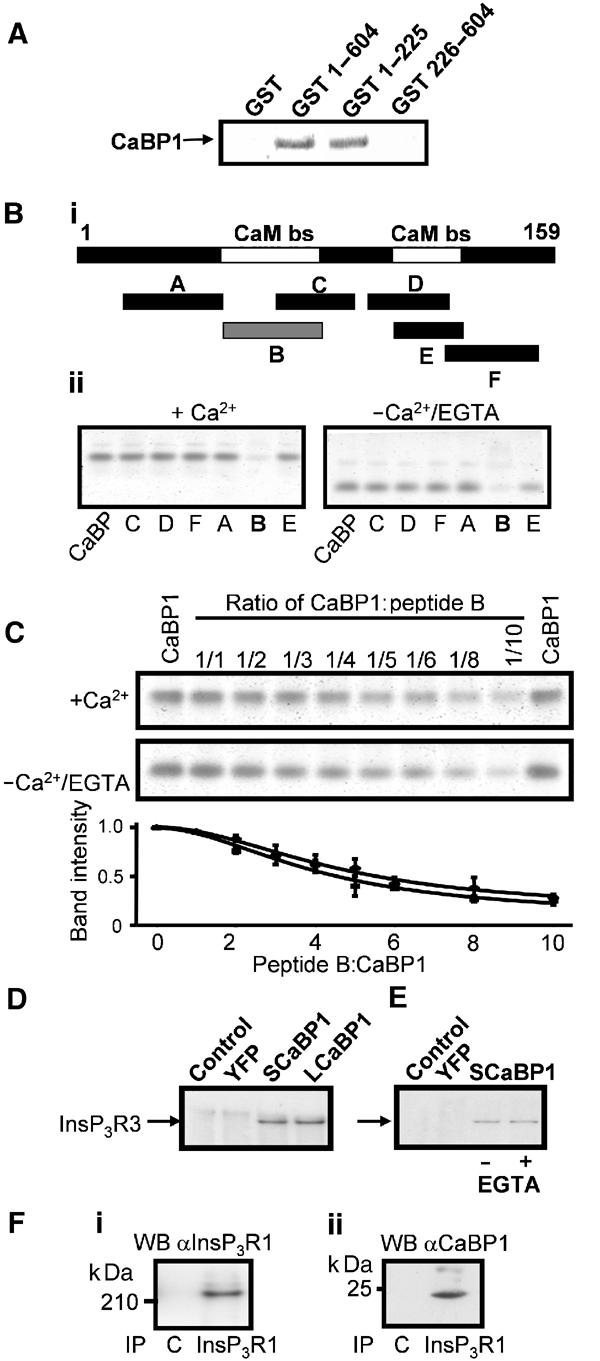

CaBP1 binds directly to the InsP3R. (A) SDS–PAGE gel, stained with SYPRO Orange™, showing the interaction between either 100 μg pGST, GST 1–604, GST 1–225, GST 226–604 or 100 μg SCaBP1 in a pull-down assay in the presence of 200 μM free Ca2+. In lanes 2 and 3, SCaBP1 was retained by GST 1–604 and GST 1–225, respectively. (Bi) Map showing positions of synthetic peptides (A–F) used for binding experiments relative to the NH2-terminal 159 aa region of the InsP3R. Peptide A (S16-N48), peptide B (P49-N81), peptide C (Y66-K91), peptide D (D97-L123), peptide E (E106-S128) and peptide F (I121-L151). White bars indicating the Ca2+-independent CaM binding sites on the InsP3R1 (Sienaert et al, 2002). Grey bar (B) showing a positive interaction of the peptide with SCaBP1. (Bii) Nondenaturating gel (15%) of 3.5 μM SCaBP1 in the presence of each of the InsP3R1 peptides (A–F) (35 μM) in 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4) containing either 200 μM free Ca2+ or 1 mM EGTA stained with SYPRO Orange™. In lane 1, SCaBP1 alone was used as a control. SCaBP1 bound to the peptide diminishes the intensity of the SCaBP1 band. (C) SDS–PAGE gel showing the interaction of SCaBP1 with increasing amounts of peptide B (P49-N81) in the presence of 200 μM Ca2+ or 1 mM EGTA stained with SYPRO Orange™. (Lower panel) Densitometric analysis of the SCaBP1 bands by ImageQuant 5.2 of the interaction between SCaBP1 and peptide B (P49-N81) in the presence of 200 μM Ca2+ (triangles) or 1 mM EGTA (squares). The vertical axis denotes the intensity of the SCaBP1 band. (D) co-IP of InsP3R3 from COS-7 cells transfected with either SCaBP1 or LCaBP-YFP. YFP-CaBP1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody. InsP3R3 immunoreactivity was detected using an anti-InsP3R3 monoclonal antibody and subsequent ECL. Transfected cDNA is indicated above the blot. (E) co-IP of InsP3R3 with SCaBP1-YFP was performed in the absence (lane 3) or presence of 1 mM EGTA (lane 4). Control IPs from YFP-transfected cells and nontransfected cells were also performed (lanes 1 and 2). (F) co-IP of CaBP with InsP3R1 from the brain. The antibody used for the IP is indicated below the blot and the antibody used for the Western blot (WB) is indicated above the blot. C indicates IP with a non-specific antibody. (Fi) IP of InsP3R1 subsequently detected by Western blot with anti-InsP3R1 antibody. (Fii) Parallel IP using an anti-InsP3R1 antibody and Western blot using an anti-CaBP antibody.

Interaction between CaBP1 and the NH2-terminal region of InsP3R1

To map the location of the CaBP-binding region within the NH2-terminus of InsP3R1, pull-down experiments using GST fusions of different NH2-terminal domains of the InsP3R1 were performed (Figure 4A). GST-(1–604) and GST-(1–225) but not GST-(226–604) or the GST control retained the purified SCaBP1. Similar results were obtained using the LCaBP-1 variant or proteins expressed without the HIS tag (data not shown). To identify the site(s) where CaBP1 interacts within the first 225 aa of the InsP3R, we performed band-shift experiments using a series of synthetic peptides spanning this region (Sienaert et al, 2002) (Figure 4Bi). A 15% nondenaturing gel illustrating the migration of SCaBP1 into the gel following incubation with a 10-fold molar excess of each of the five different peptides in either 200 μM free Ca2+ or 1 mM EGTA is shown (Figure 4Bii). The InsP3R peptides alone did not enter the gel because they were positively charged. Figure 4Bii shows that CaBP1 binds to peptide B independently of Ca2+, resulting in the formation of a complex that does not enter the gel. In a similar assay, CaM and apoCaM also interacted with peptide B (Sienaert et al, 2002), suggesting a common binding site for CaM and CaBP1. CaM and apoCaM, however, also interacted with peptide E (Sienaert et al, 2002). Since the peptide B/CaM interaction was Ca2+ independent (Sienaert et al, 2002), the Ca2+ dependence of the interaction of peptide B with SCaBP1 was investigated further. Band-shift analysis of this interaction in the presence of an increasing SCaBP1:peptide molar ratio revealed that the interaction was equally effective in the presence of 200 μM Ca2+ or 1 mM EGTA, and was thus Ca2+ independent (Figure 4C). Since our overexpression studies were carried out in COS-7 cells, we determined whether CaBP1 interacted with InsP3R3. By co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP), we demonstrated that both CaBP1 isoforms interact with InsP3R3 (Figure 4D). No co-IP of InsP3R3 was observed from lysates of control cells or from cells expressing YFP alone. Furthermore, the interaction between CaBP1 and InsP3Rs determined by co-IP was Ca2+ independent (Figure 4E). In parallel studies, co-IP of YFP-CaM with InsP3R3 from transfected cells was more difficult to obtain (data not shown). The efficient co-IP of CaBP with InsP3R1 from the brain demonstrates the physiological relevance of the CaBP–InsP3R interaction (Figure 4F).

CaBP1 inhibits InsP3 binding to InsP3Rs

We next investigated the effects of CaBP1 on InsP3 association with the ligand-binding domain of InsP3R1 (InsP3R1 aa 1–581, Lbs-1) (Sienaert et al, 2002). The presence of 5 μM Ca2+ inhibited [3H]-InsP3 binding to Lbs-1 by 22±1.9% as previously described (n=3, P<0.05) (Sienaert et al, 2002). SCaBP1 (10 μM) inhibited InsP3 binding to Lbs-1 by 36±5% in the absence of Ca2+. Inhibition by SCaBP1 was fully additive to inhibition by Ca2+, and amounted to 58±4% in the presence of Ca2+ (n=3, P<0.05). The inhibition of InsP3 binding to Lbs-1 observed for SCaBP1 was comparable to that by CaM (Ki for CaBP 1 μM compared with Ki of CaM 2 μM, data not shown). To exclude the possibility that the observed Ca2+-independent SCaBP1 effect was due to a constitutively occupied Ca2+-binding site with high affinity in the SCaBP1 protein, we used the EF hand mutant SCaBP1134. This non-Ca2+-binding mutant (10 μM) inhibited InsP3 association with Lbs-1 by 33±4% in the absence of Ca2+ and 49±5% in the presence of Ca2+. Similar results were obtained for full-length InsP3R1 (data not shown). SCaBP1 had no effect on InsP3 binding to Lbs-1 Δ1–225 (data not shown). Taken together, these results confirm that SCaBP1, like CaM, inhibits InsP3 binding to the InsP3R in a Ca2+-independent manner.

CaBP1 is regulated by phosphorylation

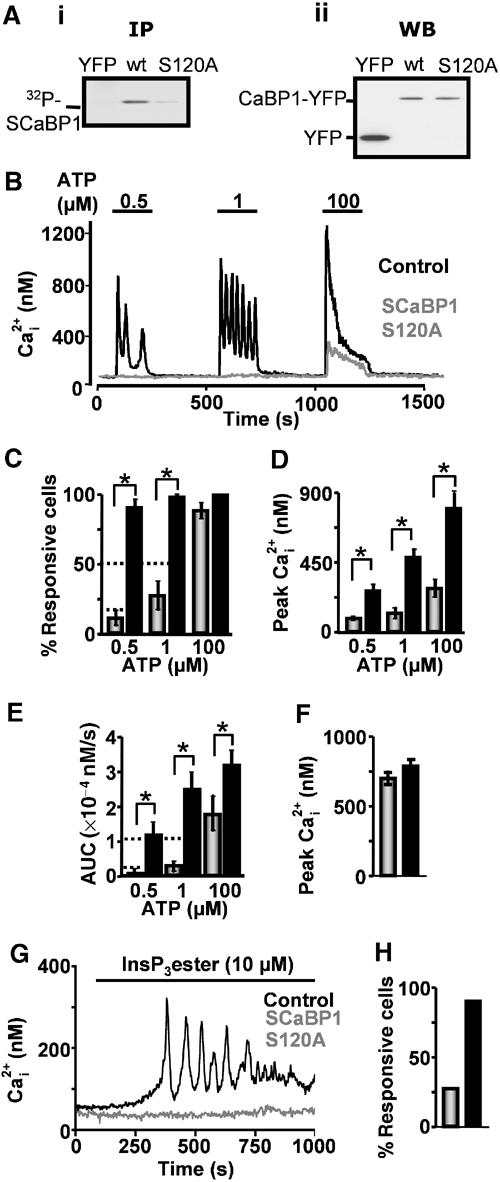

Caldendrin, the NH2-terminal extended isoform of CaBP1, is phosphorylated, although the site of phosphorylation and its function are not known (Seidenbecher et al, 1998). Using the PROSITE Database of protein families and domains (Sigrist et al, 2002), we identified a unique consensus site for phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 in SCaBP1 (S120), which is located at the COOH-terminus of its α-helical region. The functional consequence of phosphorylation of the structurally equivalent site in CaM (S101) is a decrease in its affinity for substrates (Quadroni et al, 1998). To test whether this was the case for CaBP1, the S120 residue was mutated to an alanine (S120A). By immunoprecipitation (IP) of SCaBP1-YFP from cells incubated with 32P-orthophosphate, we found that wild-type SCaBP1-YFP was phosphorylated, whereas phosphorylation of SCaBP1-S120A-YFP was barely detectable (Figure 5Ai). Equivalent levels of SCaBP1-YFP and SCaBP1-S120A-YFP in the input lysate were determined by Western blotting (Figure 5Aii) and by FACS analysis of SCaBP1-YFP-expressing cells (data not shown). When stimulated with ATP, SCaBP1-S120A-expressing cells displayed a significantly lower percentage of responding cells, lesser integrated Ca2+ signals and lower peak Ca2+ transient amplitude in comparison to control cells (Figure 5B–E). Furthermore, the degree of inhibition was significantly greater than that observed for cells expressing wild-type SCaBP1-YFP (P<0.05). No significant difference was observed in the amplitude of ionomycin-induced Ca2+ release between CaBP-S120A-expressing cells (n=14) and controls (n=43, P>0.5), indicating that the ER calcium stores were intact (Figure 5F). As shown for the wild-type CaBP (Figure 3A), the SCaBP-S120A mutant also inhibited InsP3 ester-induced Ca2+ release, indicating a direct effect on InsP3Rs (Figure 5G and H).

Figure 5.

Phosphorylation of S120 regulates CaBP1 activity. (Ai) IP using an anti-GFP antibody of SCaBP1-YFP and SCaBP1-S120A-YFP from 32P-labelled cells. Control IPs of YFP-transfected cells are also shown. (Aii) Equivalent levels of protein in the input lysate are shown in the Western blot using an anti-GFP antibody. The content of each lane is indicated in the figure. (B) Ca2+ imaging of control cells (black trace) and cells expressing SCaBP1-S120A-YFP (grey trace). (C) Number of responsive cells. (D) Peak amplitude of responses. (E) Integrated Ca2+ response (AUC). Control and CaBP-transfected cells are represented by black and grey bars, respectively. (F) Peak amplitude of Ca2+ release following ionomycin treatment (10 μM) for control cells (black bars) and SCaBP-S120A-YFP-transfected cells (grey bars). (G) Ca2+ release following stimulation with 10 μM InsP3 ester for control (black trace) and SCaBP-S120A-YFP-transfected cells (grey trace). (H) Percentage of control (black bars) and SCaBP-S120A-YFP-transfected cells (grey bars) responding to InsP3 ester stimulation is shown in the bar graph. Statistical significance is indicated by an asterisk.

Discussion

The neuronal CaBPs are a novel group of InsP3R-regulating proteins. The results presented here demonstrate a clear functional interaction between CaBP1 and the InsP3R Ca2+ release channel. Furthermore, we find that CaBP1 activity is regulated by phosphorylation. The consequences of InsP3R inhibition by CaBP1 may have great significance for neuronal Ca2+ signalling, impacting on synaptic plasticity and neuronal growth.

In this study, we characterised a cellular function of CaBP1. Our findings contrast with a previous report using an in vitro assay, which suggested that CaBP1 stimulated Ca2+ release independent of InsP3 (Yang et al, 2002). We found that both the long and short naturally occurring isoforms of CaBP1 as well as the NH2-terminally truncated cCaBP inhibited Ca2+ release induced by application of an InsP3-generating agonist when expressed in COS-7 cells. Since CaBP1 also inhibited Ca2+ release induced by application of cell-permeant InsP3 in transfected COS-7 cells, IICR from permeabilised COS cells and from intact Xenopus oocytes, we concluded that CaBP1 was directly targeting InsP3Rs. The effects of CaBP1 were not due to Ca2+ buffering, since CaBP1134, in which the three functional EF hands had been disabled, had a similar effect as the wild-type protein. Furthermore, the effects of CaBP1 on Ca2+ signalling were unlike those observed for calbindin, another EF-hand-containing protein that functions solely as a Ca2+ buffer (John et al, 2001). In addition, CaBP1 expression did not affect caffeine-induced Ca2+ release through RyRs. As well as showing specificity for IICR, these data support our conclusions that CaBP1 is not causing an artefactual adaptive response in overexpressing cells. The lack of an effect on RyRs is not surprising, since the affinity of the interaction between CaBP1 and RyRs, unlike that between CaM and RyRs, is very low (S Hamilton, personal communication). Our band-shift and co-IP data, together with the data of Yang et al (2002), which demonstrated that CaM was unable to displace CaBP1 from InsP3Rs, suggest that the affinity of the CaBP1–InsP3R interaction is greater than that between CaM and InsP3Rs. We also found that when overexpressed in COS-7 cells, CaM did not inhibit IICR to the same degree as CaBP1 (MD Bootman and HL Roderick, unpublished observations). Thus, in neurons that express InsP3Rs and RyRs, CaBP1 may serve to inhibit IICR specifically whereas CaM may target RyRs. Indeed, by co-IP from brain tissue we readily observe an interaction between CaBP and InsP3Rs, whereas an interaction between InsP3Rs and CaM is more difficult to detect (Figure 4F; K Rietdorf, MD Bootman and HL Roderick, unpublished observations).

CaM has a dual role in regulating IICR. It binds in a Ca2+-dependent manner to the regulatory domain of InsP3Rs, where it has been suggested to inactivate the receptor following Ca2+ release (Michikawa et al, 1999; Adkins et al, 2000). It also binds independently of Ca2+ to the NH2-terminus of InsP3Rs, inhibiting InsP3 binding and resultant Ca2+ release (Patel et al, 1997; Cardy and Taylor, 1998; Sipma et al, 1999; Adkins et al, 2000; Sienaert et al, 2002). Interestingly, in this study we observe that CaBP1 also binds to the NH2-terminus of the InsP3R resulting in inhibition of InsP3 binding. Unlike CaM however, which binds to two noncontiguous sequences in the first 159 aa of InsP3R1 (Sienaert et al, 2002), CaBP1 bound to the first of these sequences alone.

Like other members of the neuronal Ca2+-binding protein family of proteins, CaBP1 is myristoylated at its NH2-terminus (Haeseleer et al, 2000; Burgoyne and Weiss, 2001). In the case of hippocalcin and recoverin, an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ results in exposure of their myristoyl moieties, which results in their translocation to intracellular membranes (Burgoyne and Weiss, 2001). We find that CaBP1 is primarily localised to the plasma membrane and Golgi, but is also present in the cytosol (Figure 1B). This distribution did not change following an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ (data not shown). Furthermore, myristoylation is not required for CaBP1 activity since IICR is inhibited by recombinant CaBP and the NH2-terminally truncated CaBP1 (cCaBP). The similar levels of inhibition of IICR observed in cells expressing a myristoylation mutant (SCaBP-G2A-YFP) (Supplementary Figure 3), despite expression levels approximately two-fold higher than the wild-type protein (determined by FACS), suggest that myristoylation and thus membrane localisation increase the potency of CaBP in inhibiting IICR. Although concentrated at the plasma membrane and Golgi apparatus, CaBP clearly affects InsP3Rs. Since the Golgi apparatus is a functional InsP3-sensitive Ca2+ store (Pinton et al, 1998), CaBP is strategically located to inhibit release from this organelle. In addition, it is possible that in the dendrites where CaBP1 is endogenously expressed, myristoylation serves to target CaBP1 to the cellular membranes where its function in regulating IICR is performed. In neurons, regions of the ER lie in close proximity to the plasma membrane, which may thus facilitate an interaction between InsP3Rs and CaBP (Blaustein and Golovina, 2001). Furthermore, CaBPs may modulate other processes at the plasma membrane, for example Ca2+ influx into neurons through Cav2.1 channels (Lee et al, 2002).

The existence of a constitutive inhibitor of InsP3Rs in neurons suggests that IICR is strictly governed. As suggested for CaM, this effect may contribute to the low sensitivity of InsP3Rs reported in Purkinje neurons, which require InsP3 concentrations several orders of magnitude greater than that needed for channel opening in peripheral tissues (Khodakhah and Ogden, 1993; Cardy and Taylor, 1998; Fujiwara et al, 2001). A mechanism to allow Ca2+ release under conditions of repetitive stimulation such as during memory formation would, however, be advantageous to the cell. We identified a casein kinase 2 consensus site in SCaBP1 (S120) that is structurally conserved with a previously identified site in CaM (S101). Phosphorylation of this serine in CaM has been shown to decrease its affinity for substrates (Quadroni et al, 1998). In this study, we find that S120 is the predominant site for phosphorylation in CaBP1. Furthermore, the potency of CaBP1 in inhibiting IICR was increased by mutation of S120 to alanine. Thus, the phosphorylation status of CaBP1 may contribute to the dynamic regulation of InsP3R sensitivity in cells where it is expressed.

The data presented here contrast with that previously published (Yang et al, 2002). In that study, a truncated form of CaBP1 (cCaBP) spanning the conserved regions of long and short CaBP1 and caldendrin was used (Figure 1A). Since the NH2-terminus of other neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins is known to be important in their function, we speculated that this might also be the case for CaBP1. cCaBP, however, had a similar effect on Ca2+ signalling as the full-length wild-type protein. We also considered that a possible drawback of the heterologous expression approach used in this study is that the cell may adapt to CaBP1 overexpression, possibly by decreasing the abundance of InsP3Rs. This appeared not to be the case since IICR in Xenopus oocytes and COS cell microsomes was inhibited by recombinant CaBP. Furthermore, when IICR was investigated at earlier time points following transfection, similar, yet less dramatic, effects on Ca2+ release were observed (data not shown). In addition, as shown in Figure 1, we were also unable to detect any change in InsP3R levels.

In summary, in this study we have characterised a novel mechanism of action of a newly described InsP3R-associated neuronal Ca2+-binding protein. CaBP1 forms part of a wide array of proteins associated with InsP3Rs, which enable them to integrate multiple signalling inputs modulating Ca2+ release activity and subsequent intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis (Roderick and Bootman, 2003). In addition, CaBP1 may prove to be an important determinant of neuronal function regulating the activity of multiple partners yet to be identified. Future studies involving gene knockout and transgenic approaches will be required to resolve these issues.

Materials and methods

Generation of YFP expression vectors

cDNAs for both long and short CaBP1 were amplified by PCR from pSh-CaBP1-GFP and pLh-CaBP1-GFP, respectively (Haeseleer et al, 2000), using primers containing an Nhe1 site at the 5′ end and a HindIII site at the 3′ end. The resultant PCR products were digested with Nhe1 and HindIII, gel purified and ligated into similarly digested pEYFP-N1 (Clontech). CaBP1134 (EF hand mutant) was amplified by PCR using pGEX-CaBP1-c1m3EFH as template and primers to introduce EcoR1 restriction sites at both the 5′ and 3′ ends of the sequence. The PCR product was digested with EcoR1, gel purified and ligated into similarly digested pEYFP-N1-SCaBP1. The G2A (myristoylation site) mutant and the casein kinase 2 mutant CaBP1-S120A were generated using the Quick Change mutagenesis protocol (Stratagene). The presence of both mutations was confirmed by sequencing. To generate YFP-CaM and YFP-CaM1234, cDNAs were amplified by PCR using pAED4-hCaM and pET21B-CaM1234, respectively, as templates and primers to introduce BamH1 sites at either end of the sequence. The PCR products were digested with BamH1 and ligated into similarly digested pEYFP-C1 vector (Clontech). The calbindin cDNA was generously provided by Dr B Schwaller (University of Freiburg).

Expression of CaBP-YFP fusion proteins

COS-7 cells were plated on 22 mm coverslips in 35 mm dishes at 50–60% confluency 24 h prior to transfection. Cells were transfected using the GeneJuice™ transfection reagent (Novagen) using 1 μg of DNA per well. Experiments were performed at 48 h post-transfection unless otherwise stated.

Fura-2 imaging of transfected cells

Videoimaging of Fura-2-loaded cells was performed as previously described using a Sutter (Lambda Technologies, Brattleboro) filter wheel-based imaging system (Peppiatt et al, 2003), except that the cells were loaded with 1 μM Fura-2 AM (Molecular Probes). In addition, images of YFP-positive and -negative cells were captured using excitation at 488 nm and emission >520 nm and saved as reference.

Imaging of Xenopus oocytes

Ovaries were extracted from albino Xenopus laevis following euthanasia with 0.4% tricaine methane sulphonate (MS222). Oocytes were isolated and maintained as previously described (Camacho and Lechleiter, 2000). Oocytes were injected with Fluo-4 (Molecular Probes) to a final concentration of 40 μM 30 min prior to imaging. Imaging was performed using a Noran Oz confocal attached to a Nikon TE200 microscope equipped with a 40 × 1.4 n.a. oil immersion S-Fluor objective. The Ca2+ dye was excited by laser illumination at 488 nm. Images of 512 × 512 pixels at a 0.8 zoom were collected at 15 frames per second with a jump average of 2 and a slit width of 25 μm. Ca2+ release was initiated by injection with the nonmetabolisable InsP3 analogue F-InsP3 (Calbiochem) at final concentrations of 40 or 100 nM. Recombinant CaBP1 (described below) was either coinjected with the indicator dye 30 min prior to imaging or during image acquisition to a final concentration of 8.5 μM. This protocol has previously been successfully used to inject other Ca2+-binding proteins into oocytes (John et al, 2001). Image analysis was performed using the public domain software ImageJ (NIH, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij).

45Ca2+ fluxes

45Ca2+ fluxes were performed on saponin-permeabilised COS-1 cells as previously described (Missiaen et al, 2001). Here, 2 μM thapsigargin was added during the efflux to block the ER Ca2+ pumps. The efflux medium was replaced every 2 min during 18 min, and the efflux was performed at 25°C. The additions of 45Ca2+and InsP3 are indicated in the legends to the figures. At the end of the experiment, the 45Ca2+ remaining in the stores was released by incubation with 1 ml of a 2% sodium dodecyl sulphate solution for 30 min. Ca2+ release is plotted as the fractional loss, that is, the amount of Ca2+ released in 2 min divided by the total store Ca2+ content at that time. The latter value was calculated by summing in retrograde order the amount of tracer remaining in the cells at the end of the efflux and the amount of tracer collected during the successive time intervals.

Preparation of His-tagged CaBP1

Recombinant His-tagged long and short CaBP1 isoforms were prepared as described previously (Nadif Kasri et al, 2003).

Expression of GST fusion proteins encoding the NH2-terminal part of InsP3R1

cDNA fragments encoding different regions of the NH2-terminal part of InsP3R1 (aa 1–159, 1–225, 1–604 and 224–604) were subcloned by PCR amplification using the mouse InsP3R1 (p400C1 plasmid kindly provided by Dr K Mikoshiba, University of Tokyo) as a template into the pGEX6p2 vector. The PCR products were digested with BamHI and EcoRI, cloned in the pGEX6p vector and expressed in BL21(DE3) host cells. Expression and purification of GST fusion proteins was carried out as described previously (Sienaert et al, 1997).

Interaction between SCaBP1 and the NH2-terminal part of InsP3R1

For the pull-down assay, 100 μg of purified and dialysed GST fusion protein was rebound to glutathione-sepharose 4B beads for 2 h at 4°C. After washing (TBS/lysis buffer, Pierce, Belgium), 100 μg His-tagged SCaBP1 was added to the immobilised GST fusion proteins in the presence of 200 μM free Ca2+. Following an incubation of 2 h at 4°C, the protein complexes were washed extensively with binding buffer containing 200 μM of free Ca2+, and the retained protein was eluted by 100 mM glutathione in TBS/lysis buffer. Analysis of the eluted proteins was performed on NuPAGE® gels, 4–12% Bis–Tris in MES–SDS buffer (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and detected by Sypro™ Orange staining (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Band-shift assays by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis

The band-shift assays were performed as described previously (Sienaert et al, 2002).

InsP3 binding assay

3H-InsP3 binding to the NH2-terminal (aa 1–581) part of InsP3R1 (Lbs-1) was performed as described previously (Sipma et al, 1999). In all, 4 μg of purified Lbs-1 protein was used.

Western blotting

For CaBP expression analysis, cell lysates were prepared as described previously (Roderick et al, 2000). Extracts were prepared from either subconfluent cells isolated by trypsinisation or from YFP-positive cells isolated by FACS. A measure of 10–20 μg of the cell extract was analysed using the NuPAGE® gel system on 4–12% linear gradient gels, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed for CaBP-YFP using either polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (dilution 1:5000; Roderick et al, 1998) or a polyclonal anti-CaBP1 antibody (dilution 1:5000, UW72; Haeseleer et al, 2000). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Pierce) was used to detect immunoreactive bands after incubation of secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, dilution 1:10 000). For InsP3R analysis, COS-7 cell lysates were boiled for 2 min in Laemmli sample buffer, analysed on NuPAGE® Tris-acetate 3–8% gradient gels, transferred to Immobilon-P and probed with an isoform-specific antibody against InsP3R3 (I31220, Transduction Laboratories, dilution 1:5000). Quantification of the immunoreactive bands was performed after incubation with secondary antibodies coupled to alkaline phosphatase, detection using Vistra™ ECF (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) (Vanlingen et al, 1997).

32P labelling of CaBP-YFP

At 24 h postseeding in 60 mm Petri dishes, COS-7 cells were transfected with the appropriate CaBP1-YFP vectors. At 40 h post–transfection, cells were washed × 1 in phosphate-free MEM (ICN, cat. #1642349) containing 10% dialysed calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (labelling media). A measure of 1.5 ml of labelling media containing 0.375 μCi/ml 32P-phosphorous (orthophosphate in acid-free aqueous solution, Amersham, cat. #PBS13) was added to the cells and incubated for 6 h at 37°C. Following washing in ice-cold TBS, cells were scraped into 0.6 ml of RIPA buffer and processed for IP with 5 μl of a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody used per tube. Protein A/G sepharose (Santa Cruz) was used to capture immune complexes. Isolated proteins were incubated at 95°C for 5 min in 1 × Laemmli buffer containing β-mercaptoethanol prior to analysis through Bis–Tris NuPAGE® 4–12% linear gradient gels. Gels were fixed, dried and exposed to the film for 24 h.

Co-IP of InsP3Rs and CaBP

Lysates were prepared as described for Western blotting from 10 cm dishes of COS-7 cells expressing appropriate CaBP1-YFP constructs. Following clarification, 30 μl of each lysate was retained for Western blot analysis and the remainder diluted four-fold in lysis buffer without detergent. IP using 5 μl of anti-GFP antibody was performed and immune complexes were captured by incubation with 30 μl protein A/G sepharose. Immunoprecipitates were boiled in 30 μl sample buffer and analysed by SDS–PAGE and Western blot using a monoclonal antibody directed against the InsP3R3. Immunoreactive bands were visualised by ECL following incubation with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. For IP from rat brain, whole rat brain was disrupted with a Dounce homogeniser in cell lysis buffer described above. Following 1 h incubation on ice, the insoluble matter was isolated by centrifugation at 5000 g for 10 min. A measure of 2 mg of cell lysate was used for each IP. A polyclonal antibody against InsP3R1 was used to immunoprecipitate InsP3Rs (Parys et al, 1995).

Data analysis

For the percentage of responding cells, an average of the responding cells per coverslip was taken. A response was characterised as a deflection greater than 25 nM from baseline. The integrated Ca2+ response is the area under the Ca2+ transient minus baseline. Statistical analysis was by Student's t-test or χ2 test. Data are presented as mean±s.e.m. Significance was accepted at P<0.05 and is indicated by an asterisk.

Note added in proof

During review of this manuscript, a paper appeared in the press that described an inhibitory effect of CaBP on IICR in PC12 and HeLa cells (Haynes et al, 2003). Their findings complement our data showing an inhibition of Ca2+ release using direct stimulation of InsP3Rs.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following individuals for providing reagents: Dr K Mikoshiba (InsP3R1 cDNA), Dr K Foskett (CaBP134 cDNA), Dr F Haeseleer (long and short CaBP cDNAs and UW72 antibody), Dr Z Grabarak (CaM cDNA), Dr J Adelman (CaM1234 cDNA), Dr V Sorrentino (RyR-expressing HEK293 cells) and Dr B Schwaller (calbindin cDNA). We thank Lea Bauwens for her skilful technical assistance. This work was supported by grant 3.0207.99 from the FWO-Vlaanderen, grants P4/23 and P5/05 from the Program on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction, grant 99/08 from the Concerted Actions of the KU Leuven, The Babraham Institute, The Royal Society, and grant RGP71/2002 from the HFSP and the BBSRC. We also thank the EPSRC Mass Spectrometry service (Swansea) for mass spectra.

References

- Adkins CE, Morris SA, De Smedt H, Sienaert I, Torok K, Taylor CW (2000) Ca2+-calmodulin inhibits Ca2+ release mediated by type-1, -2 and -3 inositol trisphosphate receptors. Biochem J 345: 357–363 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL (2003) Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 4: 517–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezprozvanny I, Watras J, Ehrlich BE (1991) Bell-shaped calcium-response curves of Ins(1,4,5)P3- and calcium-gated channels from endoplasmic reticulum of cerebellum. Nature 351: 751–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein MP, Golovina VA (2001) Structural complexity and functional diversity of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ stores. Trends Neurosci 24: 602–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Roderick HL (2002) Activating calcium release through inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors without inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 7320–7322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoyne RD, Weiss JL (2001) The neuronal calcium sensor family of Ca2+-binding proteins. Biochem J 353: 1–12 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho P, Lechleiter JD (2000) Xenopus oocytes as a tool in calcium signaling research. In Calcium Signaling, Putney J (ed) pp 157–181. Boca Raton, FL: CRC [Google Scholar]

- Cardy TJ, Taylor CW (1998) A novel role for calmodulin: Ca2+-independent inhibition of type-1 inositol trisphosphate receptors. Biochem J 334: 447–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich BE (1995) Functional properties of intracellular calcium-release channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol 5: 304–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara A, Hirose K, Yamazawa T, Iino M (2001) Reduced IP3 sensitivity of IP3 receptor in Purkinje neurons. Neuroreport 12: 2647–2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Verlinde CL, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pronin AN, Benovic JL, Fariss RN, Palczewski K (2000) Five members of a novel Ca2+-binding protein (CaBP) subfamily with similarity to calmodulin. J Biol Chem 275: 1247–1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes LP, Tepikin AV, Burgoyne RD (2003) Calcium binding protein 1 is an inhibitor of agonist-evoked, inositol 1,4,5-trisphophate-mediated calcium signalling. J Biol Chem [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iino M (1999) Dynamic regulation of intracellular calcium signals through calcium release channels. Mol Cell Biochem 190: 185–190 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John LM, Mosquera-Caro M, Camacho P, Lechleiter JD (2001) Control of IP(3)-mediated Ca2+ puffs in Xenopus laevis oocytes by the Ca2+-binding protein parvalbumin. J Physiol 535: 3–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi S, Yasuda S, Yamazaki R, Teshima Y, Kanda K, Kakiuchi R, Sobue K (1982) Quantitative determinations of calmodulin in the supernatant and particulate fractions of mammalian tissues. J Biochem, (Tokyo) 92: 1041–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodakhah K, Ogden D (1993) Functional heterogeneity of calcium release by inositol trisphosphate in single Purkinje neurones, cultured cerebellar astrocytes, and peripheral tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 4976–4980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A, Westenbroek RE, Haeseleer F, Palczewski K, Scheuer T, Catterall WA (2002) Differential modulation of Ca(v)2.1 channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein 1. Nat Neurosci 5: 210–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michikawa T, Hirota J, Kawano S, Hiraoka M, Yamada M, Furuichi T, Mikoshiba K (1999) Calmodulin mediates calcium-dependent inactivation of the cerebellar type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Neuron 23: 799–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiaen L, Van Acker K, Parys JB, De Smedt H, Van Baelen K, Weidema AF, Vanoevelen J, Raeymaekers L, Renders J, Callewaert G, Rizzuto R, Wuytack F (2001) Baseline cytosolic Ca2+ oscillations derived from a non-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ store. J Biol Chem 276: 39161–39170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadif Kasri N, Bultynck G, Sienaert I, Callewaert G, Erneux C, Missiaen L, Parys JB, De Smedt H (2002) The role of calmodulin for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor function. Biochim Biophys Acta 1600: 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadif Kasri N, Sienaert I, Parys JB, Callewaert G, Missiaen L, Jeromin A, De Smedt H (2003) A novel Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mechanism in A7r5 cells regulated by calmodulin-like proteins. J Biol Chem 278: 27548–27555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase T, Ito KI, Kato K, Kaneko K, Kohda K, Matsumoto M, Hoshino A, Inoue T, Fujii S, Kato H, Mikoshiba K (2003) Long-term potentiation and long-term depression in hippocampal CA1 neurons of mice lacking the IP(3) type 1 receptor. Neuroscience 117: 821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Barbara JG, Nakamura K, Ross WN (1999) Synergistic release of Ca2+ from IP3-sensitive stores evoked by synaptic activation of mGluRs paired with backpropagating action potentials. Neuron 24: 727–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parys JB, de Smedt H, Missiaen L, Bootman MD, Sienaert I, Casteels R (1995) Rat basophilic leukemia cells as model system for inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor IV, a receptor of the type II family: functional comparison and immunological detection. Cell Calcium 17: 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Joseph SK, Thomas AP (1999) Molecular properties of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Cell Calcium 25: 247–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Morris SA, Adkins CE, O'Beirne G, Taylor CW (1997) Ca2+-independent inhibition of inositol trisphosphate receptors by calmodulin: redistribution of calmodulin as a possible means of regulating Ca2+ mobilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 11627–11632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peppiatt CM, Collins TJ, Mackenzie L, Conway SJ, Holmes AB, Bootman MD, Berridge MJ, Seo JT, Roderick HL (2003) 2-Aminoethoxydiphenyl borate (2-APB) antagonises inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release, inhibits calcium pumps and has a use-dependent and slowly reversible action on store-operated calcium entry channels. Cell Calcium 34: 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton P, Pozzan T, Rizzuto R (1998) The Golgi apparatus is an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ store, with functional properties distinct from those of the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J 17: 5298–5308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadroni M, L'Hostis EL, Corti C, Myagkikh I, Durussel I, Cox J, James P, Carafoli E (1998) Phosphorylation of calmodulin alters its potency as an activator of target enzymes. Biochemistry 37: 6523–6532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick HL, Bootman MD (2003) Bi-directional signalling from the InsP3R: regulation by calcium and accessory factors. Biochem Soc Trans 31: 950–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick HL, Lechleiter JD, Camacho P (2000) Cytosolic phosphorylation of calnexin controls intracellular Ca2+ oscillations via an interaction with SERCA2b. J Cell Biol 149: 1235–1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roderick HL, Llewellyn DH, Campbell AK, Kendall JM (1998) Role of calreticulin in regulating intracellular Ca2+ storage and capacitative Ca2+ entry in HeLa cells. Cell Calcium 24: 253–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Simeoni I, Micheli M, Bootman M, Lipp P, Allen PD, Sorrentino V (2002) RyR1 and RyR3 isoforms provide distinct intracellular Ca2+ signals in HEK 293 cells. J Cell Sci 115: 2497–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher CI, Langnaese K, Sanmarti-Vila L, Boeckers TM, Smalla KH, Sabel BA, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, Kreutz MR (1998) Caldendrin, a novel neuronal calcium-binding protein confined to the somato-dendritic compartment. J Biol Chem 273: 21324–21331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienaert I, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Parys JB, Sipma H, Casteels R (1997) Molecular and functional evidence for multiple Ca2+-binding domains in the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. J Biol Chem 272: 25899–25906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienaert I, Nadif Kasri N, Vanlingen S, Parys JB, Callewaert G, Missiaen L, de Smedt H (2002) Localization and function of a calmodulin–apocalmodulin-binding domain in the N-terminal part of the type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Biochem J 365: 269–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist CJ, Cerutti L, Hulo N, Gattiker A, Falquet L, Pagni M, Bairoch A, Bucher P (2002) PROSITE: a documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Brief Bioinform 3: 265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipma H, De Smet P, Sienaert I, Vanlingen S, Missiaen L, Parys JB, De Smedt H (1999) Modulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate binding to the recombinant ligand-binding site of the type-1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor by Ca2+ and calmodulin. J Biol Chem 274: 12157–12162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder SH, Supattapone S (1989) Isolation and functional characterization of an inositol trisphosphate receptor from brain. Cell Calcium 10: 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CW, Laude AJ (2002) IP3 receptors and their regulation by calmodulin and cytosolic Ca2+. Cell Calcium 32: 321–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas D, Lipp P, Tovey SC, Berridge MJ, Li W, Tsien RY, Bootman MD (2000) Microscopic properties of elementary Ca2+ release sites in non-excitable cells. Curr Biol 10: 8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrower EC, Hagar RE, Ehrlich BE (2001) Regulation of Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor isoforms by endogenous modulators. Trends Pharmacol Sci 22: 580–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlingen S, Parys JB, Missiaen L, De Smedt H, Wuytack F, Casteels R (1997) Distribution of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor isoforms, SERCA isoforms and Ca2+ binding proteins in RBL-2H3 rat basophilic leukemia cells. Cell Calcium 22: 475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe P, Villa A, Damiani E, Sharp AH, Podini P, Snyder SH, Meldolesi J (1991) Heterogeneity of microsomal Ca2+ stores in chicken Purkinje neurons. EMBO J 10: 3183–3189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojcikiewicz RJ (1995) Type I, II, and III inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors are unequally susceptible to down-regulation and are expressed in markedly different proportions in different cell types. J Biol Chem 270: 11678–11683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, McBride S, Mak DO, Vardi N, Palczewski K, Haeseleer F, Foskett JK (2002) Identification of a family of calcium sensors as protein ligands of inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 7711–7716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Data