Abstract

Candida dubliniensis is a newly identified species of Candida that is phenotypically similar to but genetically distinct from C. albicans. This organism has been recovered with increasing frequency from the oral cavities of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and AIDS patients and has been implicated as a causative agent of oral candidiasis and systemic disease. In the present study we characterized the molecular mechanisms of resistance to fluconazole (FLC) in C. dubliniensis clinical isolates from two different HIV-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Isolates were identified to the species level by phenotypic and genotypic tests. DNA-typing techniques were used to assess strain identity. Antifungal susceptibility testing was performed by NCCLS techniques. Northern blotting analysis was used to monitor the expression of genes encoding lanosterol demethylase (ERG11) and efflux transporters (CDR and MDR1) in matched sets of C. dubliniensis-susceptible and -resistant isolates by using probes generated from their homologous C. albicans sequences. In addition, ERG11 genes were amplified by PCR, and their nucleotide sequences were determined in order to detect point mutations with a possible effect in the affinity for azoles. Decreasing susceptibilities to FLC were detected in C. dubliniensis isolates recovered from both patients during the course of treatment. FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates from one patient demonstrated combined upregulation of the MDR1, CDR1, and ERG11 genes. Among the isolates from the second patient, all isolates showing decreased susceptibility to FLC demonstrated upregulation of MDR1, whereas the levels of mRNA for the ERG11 genes remained constant and the expression of CDR genes was negligible. Fourteen point mutations were found in the ERG11 genes of the isolates with decreased susceptibility to FLC. These data demonstrate that the development of azole resistance in C. dublinensis clinical isolates from HIV-infected patients treated with FLC is mediated by multiple molecular mechanisms of resistance, similar to the observations found in the case of C. albicans.

Candida dubliniensis is a newly identified species of Candida that is phenotypically similar to (chlamydospore and germ tube positive) but genetically distinct from C. albicans (5, 8, 20, 42, 43, 44). The vast majority of C. dubliniensis isolates have been recovered from the oral cavities of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected adults and children and patients with AIDS, most often in combination with C. albicans and/or other Candida species. C. dubliniensis has been implicated as a causative agent of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), particularly in patients with recurrent infections (3-6, 10, 14, 21, 26, 30, 33, 37, 41, 42). In addition, oral carriage of C. dubliniensis has been found and C. dubliniensis has been implicated as a causative organism in oral candidiasis in HIV-negative individuals, including healthy and diabetic individuals (5, 40, 47). Similarly, C. dubliniensis has been recovered from specimens from a variety of other anatomical sites, including feces, sputum, urine, wounds, the vagina, and the respiratory tract (13, 26). Finally, this organism has been implicated in clinically documented invasive infections in HIV- and non-HIV-infected populations, affecting individuals with severe underlying diseases (2, 22, 39).

Azole derivatives, particularly fluconazole (FLC), are effective in the treatment of mucosal candidiasis, even in patients with advanced immunodeficiency, and constitute the standard treatment for this disease (40). The vast majority of C. dubliniensis clinical isolates are susceptible to commonly used and experimental antifungal drugs (29). Recently, our group and others have also reported on the development of FLC resistance in C. dubliniensis clinical isolates from HIV-infected patients with OPC with prior exposure to FLC (14, 34). In addition, derivatives exhibiting a stable phenotype of FLC resistance have already been generated in vitro from FLC-susceptible isolates by growing colonies on medium containing increasing concentrations of the drug (23). Subsequent molecular studies showed that the primary resistance mechanism in FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis derivatives obtained in vitro was upregulation of the major facilitator Mdr1p (24). The emergence of resistance to azole derivatives and the underlying molecular mechanisms are well documented for C. albicans isolates from patients with AIDS and recurrent OPC after long exposures to the drug (17, 28, 31, 46). Phenotypically stable resistance to azole antifungal agents in C. albicans can result from mutations in or increased levels of expression of the genes involved in the ergosterol synthesis pathway and increased levels of expression of ATP-binding cassette transporters and major facilitator efflux pumps (17, 34, 35). However, similar molecular studies with C. dubliniensis clinical isolates are lacking. In this study, we report on the underlying molecular mechanisms responsible for the development of FLC resistance in C. dubliniensis clinical isolates from two HIV-infected patients with OPC who were repeatedly exposed to the drug.

(This work was presented in part at the 100th General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology, Los Angeles, Calif., 2000, and at the 40th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Specimen collection.

Clinical samples were obtained from HIV-infected patients enrolled in a prospective clinical study of OPC at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and the Audie L. Murphy Division, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio (31). All patients had advanced AIDS when they were enrolled in the study and had mean CD4 cell counts of <50/mm3. Samples for culture were obtained weekly during therapy and quarterly for surveillance by the use of oral saline rinses or by directly swabbing the oral lesion. At the time of initial isolation, oral samples were plated on RPMI and CHROMagar Candida (Paris, France) with FLC (8 and 16 μg/ml) and without FLC to maximize detection of resistant Candida yeasts, as described previously (17, 27). The color of the isolates was recorded, and three to five yeast colonies from each culture were randomly selected and stored on Sabouraud dextrose slants at −70°C. The patients were initially treated with FLC at a dose of 100 mg/day. The FLC doses were increased up to 800 mg/day for those individuals who developed clinical resistance, defined as the clinical requirement for increasing FLC doses for a response. C. dubliniensis isolates were tested for FLC susceptibility (NCCLS methodology) and were considered resistant when the FLC MIC for the isolate was ≥64 μg/ml (25, 32).

Phenotypic characterization.

Phenotypic characterization of these isolates was performed by the use of germ tube formation in human serum at 37°C for 3 h, differential growth at 37 and 42°C on Sabouraud dextrose agar (BBL, Cockeysville, Md.), identification with the API 20C system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France), and the color of the colonies in chromogenic medium (CHROMagar Candida) (12). Isolates were subcultured onto plates containing Sabouraud dextrose agar 48 h prior to propagation in YEPD medium (2% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% glucose).

Reference strains.

Two reference strains, C. albicans reference strain NCPF 3153A and C. dubliniensis type strain NCPF 3949, were included in this study.

Genotypic identification and DNA-typing techniques.

Strain identity was established by karyotyping, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, and DNA fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive Ca3 probe from C. albicans and the Cd25 probe from C. dubliniensis, as described previously (12, 17, 28, 38). Hybridization with the Cd25 probe was also used as genotypic tool to confirm the identities of the isolates as C. dubliniensis. Chromosomal DNA from each isolate was prepared in agarose plugs and was separated by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). RFLP patterns were obtained by digestion of chromosomal DNA with SfiI and EcoRI (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.). The digested DNA present in the RFLP gels was transferred to nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell, Inc., Keene, N.H.) and hybridized with the Ca3 probe and subsequently with the Cd25 probe, radioactively labeled by random priming (Random Primers DNA Labeling system; Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.), and exposed to autoradiography film (Du Pont, Wilmington, Del.) overnight at −70°C. The resulting banding patterns were analyzed visually and by using computer-assisted methods (Dendron; Solltech Inc., Oakdale, Iowa).

Drug susceptibility testing.

Testing of the susceptibilities of the isolates to FLC (Pfizer Inc., Sandwich, United Kingdom), itraconazole (Janssen Pharmaceutica, Beerse, Belgium), voriconazole (Pfizer Inc.), posaconazole (SCH56592; Schering Plough, Kenilworth, N.J.), ravuconazole (Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute, Wallingford, Conn.), amphotericin B (Bristol-Myers Squibb), and caspofungin (MK-0991; Cancidas; Merck, Rahway, N.J.) was done by a broth microdilution method according to the methodology of NCCLS (25).

Northern blot analysis.

Cells were inoculated in fluconazole-free YEPD medium and were harvested while they were growing in the logarithmic phase at an approximate cell density of 7.5 × 107 cells/ml. Total RNA was obtained with an RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Santa Clarita, Calif.) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Equal amounts (approximately 5 μg) of RNA, as determined by measurement of the A260, were separated by electrophoresis and were subsequently transferred to nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell) with a Turboblotter apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell). Probes specific for the ERG11, MDR1, CDR, CDR1, and CDR2 genes were purified from plasmids containing inserts of the respective genes from C. albicans, as described before (17). In the case of the MDR1-specific probe, as has been shown previously, C. dublinienis and C. albicans MDR1 genes are highly homologous, being 92% identical at the nucleotide sequence level and 96.2% identical at the protein level. In the case of CDR-specific probes, the homologies between C. albicans and C. dubliniensis CDR1 and CDR2 at the nucleotide level are 91 and 98%, respectively (24). In our study we used three different probes for CDR genes: a CDR-specific probe, which is based on the whole sequence of C. albicans CDR1 and which has been shown to cross-hybridize with other members of this gene family, and CDR1- and CDR2-specific probes, which are specific for these two genes, which have less than 50% homology at the nucleotide sequence level (17, 24). All probes were labeled by random priming (Random Primers DNA Labeling system; Gibco BRL), and hybridizations were performed with Rapid-hyb buffer (Amersham Life Science Inc., Arlington Heights, Ill.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. After hybridization, the blots were washed under high-stringency conditions and were exposed to autoradiography film (Kodak) overnight at room temperature. Nylon membranes were probed sequentially with the different probes following stripping of the previously bound probe with heated (95°C) 1× SSC buffer (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 15 mM sodium citrate [pH 7.0]) with 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate twice for 15 min each time. For densitometric analysis, autoradiograms were scanned with the Adobe Photoshop program (Adobe Systems Inc., Mountain View, Calif.) and the signals were quantitated with Dendron software (Solltech Inc.). Relative values were adjusted for differences in sample loading based on quantification of 18S rRNA levels. A twofold increase in the densitometric values compared to the level of expression in matched susceptible isolates was arbitrarily identified as significant (upregulation). Figures 1 and 2 were prepared with the Adobe Photoshop program.

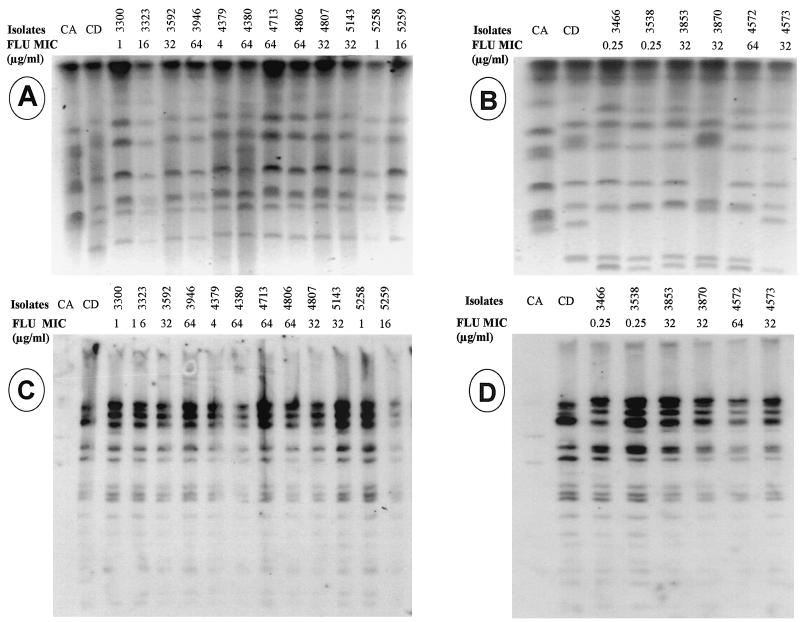

FIG. 1.

(A and C) Patient 1. (A) Karyotyping; (C) fingerprinting analysis of EcoRI digests with the Cd25 probe. Lanes CA, C. albicans reference strain 3153A; lanes CD, C. dubliniensis reference strain NCPF 3949; the remaining lanes contain clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis. (B and D) Patient 2. (B) Karyotyping; (D) fingerprinting analysis of EcoRI digests with the Cd25 probe. Lanes CA, C. albicans reference strain 3153A; lanes CD, C. dubliniensis reference strain NCPF 3949; the remaining lanes contain clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis. FLU, fluconazole.

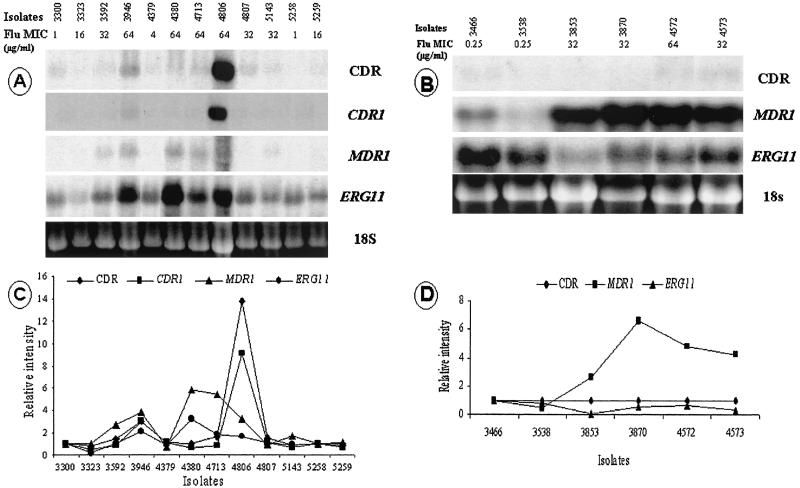

FIG. 2.

(A and B) Northern analysis of total RNA from C. dubliniensis clinical isolates from patients 1 and 2 with ERG11, MDR1, and CDR genes from C. albicans as probes. (C and D) The signal intensities of the levels of mRNA for CDR, MDR1, and ERG11 were quantified densitometrically and normalized to the intensity of the susceptible isolate. 18S rRNA was used to standardize signal levels according to lane loading parameters. Flu, fluconazole.

Cloning and sequencing of ERG11 genes from C. dubliniensis isolates.

The ERG11 genes were amplified from the genomic DNA of the C. dubliniensis isolates by PCR. Genomic DNA was extracted with the YeaStar Genomic DNA system (Zymo Research, Orange, Calif.) and was used as a template for amplification of the ERG11 genes with the following primers: 5′ GCG GAT CCT TAA AAC ATA CAA GTT TCT CTT TT 3′ and 5′ ACG CGT CGA CAA TAT GGC TAT TGT TGA AAC TGT C 3′. The sequences of these primers have previously been shown to span the entire C. albicans ERG11 open reading frame (28). PCRs were carried out in a 100-μl volume containing 100 ng of genomic DNA; each primer at a concentration of 300 nM; dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP, each at a concentration of 350 μM; 1.75 mM PCR buffer with MgCl2; and 0.75 μl of an enzyme mixture (Thermostable Taq and Pwo polymerases). The Expand Long Template PCR system (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) was used. Amplification was performed in a thermal cycler (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, Mass.) for 1 cycle of 4 min at 94°C and then for 30 cycles, each of which consisted of 30 s at 94°C, 1 min at 54°C, and 2 min at 68°C; this was followed by 1 final cycle similar to the previous 30 cycles but with 7 min at 68°C. The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels and were visualized by transillumination after staining of the gels with ethidium bromide. The PCR products were subsequently cloned into the pCR 2.1 vector system (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The insert DNAs of the recombinant plasmids were sequenced by primer elongation with an automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Both strands of all the clones were sequenced. For C. dubliniensis type strain NCPF 3949, the sequences of both strands of three independent clones were obtained.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequence of C. dublinienis type strain NCPF 3949 ERG11 has been deposited in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under accession no. AY034876.

RESULTS

Case reports.

FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates were isolated from two patients with AIDS and prior episodes of OPC who were receiving treatment with FLC. In patient 1, at the initial episode of OPC under study, C. albicans (FLC MIC, 0.5 μg/ml) and C. glabrata (FLC MIC, 64 μg/ml) were both detected in the oral sample. The patient was treated with 100 mg of FLC per day for a week, and a great improvement was observed, but with a single, localized lesion being maintained. C. albicans was no longer isolated, C. glabrata (FLC MIC range, 16 to >64 μg/ml) persisted, and C. dubliniensis (FLC MIC range, 1 to 16 μg/ml) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (FLC MIC range, 16 to >64 μg/ml) were first detected. A clinical response to FLC occurred after administration of a dose of 100 mg/day for 14 days. Both C. dubliniensis (FLC MIC range, 16 to >64 μg/ml) and C. glabrata persisted in quarterly surveillance cultures, even though treatment with FLC at 200 mg/day was suppressive. FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis was continuously isolated along with C. glabrata for a period of 8 months, after which C. dubliniensis could not be recovered again, coinciding with immunological recovery (CD4 lymphocyte count, >200/mm3) and an undetectable viral load (<400 copies/ml) while the patient was receiving treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). The patient did not present with an OPC relapse and remained free of symptoms, despite the persistent colonization with FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates. In the second patient, FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis appeared after five episodes of recurrent mixed OPC (C. albicans [FLC MIC range, 0.5 to 64 μg/ml] and C. dubliniensis [FLC MIC range, 0.25 to 64 μg/ml]) treated with high doses of FLC on an intermittent basis. At the time of presentation of FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis, the patient was not responding to HAART, had a severely compromised immunological status, and had clinical symptoms of OPC.

Strain identification.

The oral samples were plated in chromogenic and RPMI media with and without FLC. Among the isolates with decreased susceptibilities to azoles (MICs, ≥16 μg/ml), 9 of 13 were recovered from plates not containing FLC. Among the isolates from patient 1, all the isolates for which the MIC was in the range of 16 to 32 μg/ml and two of the four isolates for which the MIC was 64 μg/ml were originally isolated from plates not containing FLC. Among the isolates from patient 2, the three isolates for which the MIC was 32 μg/ml were recovered from plates with FLC, while the isolate for which the FLC MIC was 64 μg/ml was recovered from a plate without FLC. Since evaluation of the molecular mechanisms of resistance requires the use of matched sets of susceptible and resistant isolates, DNA-typing techniques were used to assess the isogenicities between a total of five highly resistant isolates (FLC MICs, ≥64 μg/ml) selected for analysis and their corresponding susceptible isolates recovered from both HIV-infected patients. For each patient, the currently available DNA-typing techniques indicated the development of resistance in a persistent strain. A high degree of relatedness among susceptible and resistant isolates obtained from the same patient was confirmed by all typing methods used (karyotyping, RFLP analysis, and fingerprinting with C. dubliniensis-specific probe Cd25). A Dendron similarity coefficient (SAB) of ≥0.9 was obtained when the dendrograms computed by use of the patterns obtained by karyotyping and with the Cd25 probe for all isolates from patient 1 were compared. In the case of patient 2, because of the different patterns obtained for isolates 3870 and 4573 by karyotyping, the SAB coefficient computed by use of those patterns was 0.7. However, because these isolates had the same patterns by RFLP (SfiI) analysis and analysis with the Cd25 probe as the other isolates, they were considered substrains or variants of the same persistent strain rather than different unrelated strains. These results also demonstrated that each patient harbored a different C. dubliniensis strain (Fig. 1).

Antifungal susceptibility testing.

The MICs of FLC, itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole, ravuconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin for the different isolates are summarized in Table 1. The initial isolate of the series from each patient was FLC susceptible (FLC MIC, ≤8 μg/ml). Although the MICs of itraconazole, as well as those of the newer triazole agents, remained quite low (≤1 μg/ml) for all the FLC-resistant isolates studied, decreased susceptibilities to itraconazole, voriconazole, and ravuconazole were detected among the FLC-resistant isolates from patient 1, with the increases in the MICs being up to 4 twofold dilutions for some isolates. Decreased susceptibility to posaconazole was also noted among FLC-resistant isolates from patient 1, with the increases in the MICs being 2 twofold dilutions. Similarly, decreased susceptibilities to itraconazole and voriconazole were detected among the FLC-resistant isolates from patient 2, with the increases in the MICs being 3 to 5 twofold dilutions. A slight decrease in susceptibility to posaconazole was also noted among the FLC-resistant isolates, with the increases in the MICs being 1 twofold dilution. Despite the increase in the MICs of the triazoles tested, all isolates, including the FLC-resistant strains, remained susceptible to these antifungals. Susceptibility to caspofungin remained stable regardless of the change in triazole susceptibility. Likewise, no cross-resistance to amphotericin B was observed.

TABLE 1.

Susceptibilities of C. dubliniensis isolates from AIDS patients to a panel of antifungal agents

| Patient no. | Isolate | Sourcea | Date (mo/day/yr) | MICs (μg/ml) at 24 h/48 hb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLC | ITC | VRC | PSZ | RAV | AMB | MKc | ||||

| 1 | 3300 | C-0 | 7/15/96 | 0.5/1 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 |

| 3323 | C-0 | 7/22/96 | 8/16 | 0.03/0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.015/0.06 | 0.03/0.25 | 0.06/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 3592 | C-0 | 10/22/96 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.125/0.25 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.016/0.06 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 3946 | C-0 | 2/14/97 | 2/64 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.008/0.03 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4379 | C-8 | 7/10/97 | 4/4 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.03/0.06 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.008/0.016 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4380 | C-16 | 7/10/97 | 32/64 | 0.03/0.25 | 0.25/0.25 | <0.015/0.06 | <0.008/0.25 | 0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4713 | C-8 | 9/9/97 | 32/64 | <0.015/0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.015/0.06 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4806 | C-0 | 10/8/97 | 32/64 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.125/0.125 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.016/0.006 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4807 | C-0 | 10/8/97 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.125/0.125 | <0.015/0.03 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 5143 | C-0 | 1/8/98 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.125/0.25 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.016/0.06 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 5258 | C-0 | 1/8/98 | 1/1 | <0.015/0.03 | <0.015/0.06 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 5259 | C-0 | 1/8/98 | 8/16 | <0.015/0.03 | 0.03/0.25 | <0.015/<0.015 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 2 | 3466 | C-0 | 9/4/96 | 0.25/0.25 | <0.015/0.03 | <0.015/0.03 | <0.015/0.06 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 |

| 3538 | C-0 | 10/14/96 | <0.125/0.25 | <0.015/0.125 | <0.015/0.125 | <0.015/0.125 | <0.008/0.016 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 3853 | C-8 | 1/29/97 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.125 | <0.015/0.25 | 0.03/0.125 | 0.125/0.25 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 3870 | C-8 | 2/6/97 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.25/0.25 | 0.06/0.125 | 0.125/0.25 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4572 | C-0 | 8/19/97 | 32/64 | <0.015/0.25 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.015/0.125 | 0.25/0.5 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

| 4573 | C-8 | 8/19/97 | 16/32 | <0.015/0.06 | <0.015/0.06 | <0.015/0.06 | 0.06/0.25 | <0.03/0.06 | 0.5/0.5 | |

C-0, CHROMagar without FLU; C-8, CHROMagar with 8 μg of FLC/ml; C-16, CHROMagar with 16 μg of FLC/ml.

ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; PSZ, posaconazole; RAV, ravuconazole; AMB, amphotericin B; MK, caspofungin.

RPMI medium was used.

Expression of ERG11, MDR1, and CDR genes in fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates.

To determine if FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis clinical isolates exhibited increased levels of expression of the ERG11, MDR1, and CDR genes, which are involved in azole resistance, Northern blotting analysis of total cellular RNA extracted from the different isolates growing in YEPD medium in the absence of an antifungal drug was performed with probes obtained from their homologous C. albicans ERG11, MDR1, CDR, CDR1, and CDR2 sequences. In isolates from patient 1, upregulation of ERG11 and/or genes encoding efflux pumps was found for all clinical isolates with high-level resistance to FLC (MICs, ≥64 μg/ml) and one of the isolates with decreased fluconazole susceptibility (MIC = 32 μg/ml). By comparison with the fluconazole-susceptible isogenic isolates, overexpression of the CDR and CDR1 genes was detected for isolates 3946 and 4806, and this was associated with the concomitant upregulation of MDR1 and ERG11. No CDR2 upregulation was found for any of these isolates. Upregulation of MDR1 was observed for isolates 3592, 4380, and 4713; and upregulation of the ERG11 gene was found for isolate 4380. The two remaining isolates had decreased susceptibilities to fluconazole (MIC, 32 μg/ml), but no upregulation of genes encoding efflux pumps or of ERG11 was found. Among the isolates from patient 2, the only mechanism of resistance present in the FLC-resistant isolate (isolate 4572) and the isolates showing decreased susceptibility to fluconazole (isolates 3853, 3870, and 4573) was upregulation of MDR1; the FLC-susceptible isogenic isolates did not upregulate this gene (Fig. 2).

Identification of ERG11 gene in C. dubliniensis type strain.

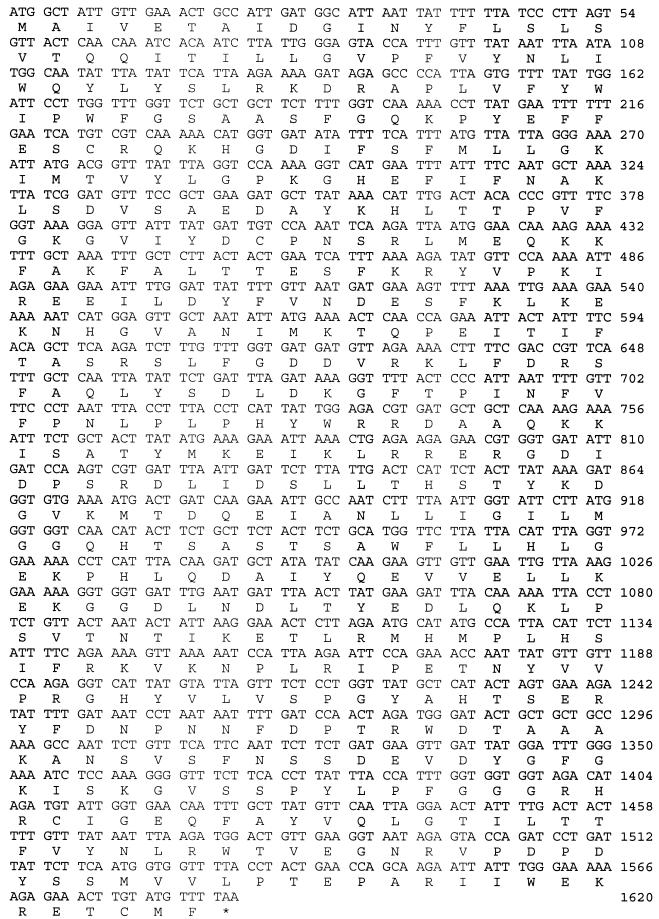

The ERG11 gene was amplified from the genomic DNA of the C. dubliniensis type strain by PCR with high-fidelity DNA polymerase and primers that have previously been shown to span the entire C. albicans ERG11 open reading frame. A fragment of the expected length (1.6 kb) was obtained, cloned, and subsequently sequenced. The sequences of both strands from three independent clones were obtained, with identical results. Figure 3 shows the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of C. dubliniensis lanosterol 14α-demethylase. At the DNA level, the sequence is highly similar to that of C. albicans (92% homology). The deduced amino acid sequence is also highly similar, both in size (528 amino acids) and in amino acid homology (96% amino acid identity) (15). The comparison of both sequences confirmed that the structurally and functionally important residues, such as the heme binding residues, the residues that interact with the redox-partner protein and/or that are involved in electron transfer, the residues that line the substrate access channel, and the substrate binding residues, are conserved in the C. dubliniensis lanosterol 14α-demethylase (1, 11, 36).

FIG.3.

Nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence of C. dubliniensis lanosterol 14α-demethylase. ∗, stop codon.

Mutations in ERG11 genes from C. dubliniensis isolates with decreased susceptibilities to azole antifungal agents.

In order to identify whether point mutations were present in the ERG11 genes of C. dubliniensis isolates with decreased susceptibilities to azoles, we obtained their sequences as described in Materials and Methods. All the sequences contained at least one cryptic nucleotide variation compared to the ERG11 sequence of the C. dubliniensis type strain (data not shown). As shown in Table 2, a total of 14 different nucleotide changes in ERG11 alleles from clinical C. dubliniensis isolates yielded 14 different amino acid substitutions compared to the sequence of the C. dubliniensis type strain. Most of these substitutions were found in combination. Four of these mutations (F126L, G307A, V437A, and G464S) have previously been described in azole-resistant C. albicans clinical isolates (16, 18, 19, 28, 36). The V125L, F126L, and V437A mutations were found in ERG11 genes from both azole-susceptible and azole-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates and therefore are not likely to represent mutations linked with an phenotype of resistance to an azole antifungal agent. Only the G307A and G464S mutations have been shown, using functional expression of the genes in S. cerevisiae, to decrease the affinity of the target enzyme for the azoles in C. albicans clinical isolates (28, 36). The other nine mutations (S113F, F148L, T199A, R210G, D288G, G289D, L300P, R398G, and P515S) have not been described in C. albicans.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid substitutions in ERG11 genes from C. dubliniensis clinical isolates

| Patient no. | Isolate | FLC MIC (μg/ml) | Substitutiona

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S113F | V125A | F126L | F148L | T199A | R210G | D288G | G289D | L300P | G307A | R398G | V437A | G464S | P515S | |||

| 1 | 3300 | 1 | T374C | C378A | T1310C | |||||||||||

| 3946 | 64 | C378A | A595G | A628G | ||||||||||||

| 4380 | 64 | G1390A | ||||||||||||||

| 4713 | 64 | G1390A | ||||||||||||||

| 4806 | 64 | T442C | G920C | C1543T | ||||||||||||

| 4807 | 32 | A863G | T899C | T1310C | ||||||||||||

| 5143 | 32 | T374C | C378A | A1192G | T1310C | |||||||||||

| 2 | 3466 | 0.25 | ||||||||||||||

| 4572 | 64 | C338T | G866A | |||||||||||||

The base numbers are with respect to the first ATG codon of ERG11.

DISCUSSION

C. dubliniensis is a newly described species that has been identified as an important cause of mucosal colonization and infection in HIV-infected individuals (42). Stable FLC resistance can be induced in vitro after exposure to this drug (23). In addition, FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates have been isolated from clinical samples of AIDS patients exposed to FLC for prolonged periods of time (14, 34). However, the clinical significance of this finding remains unclear.

The purpose of the present study was to determine the nature of the molecular mechanisms of resistance to FLC in C. dubliniensis clinical isolates from two HIV-infected patients with OPC who were undergoing treatment with this drug. Because C. dubliniensis is usually found in mixed cultures with C. albicans, several phenotypic methods for identification and discrimination from C. albicans were used in this study, including formation of dark green colonies on CHROMagar Candida medium, negligible or no growth at 42°C, and distinctive carbohydrate assimilation profiles (14). Furthermore, a specific C. dubliniensis fingerprinting probe, Cd25, was used to confirm the identities of the C. dubliniensis isolates analyzed in this study at the genotypic level. It has been demonstrated that C. dubliniensis can develop FLC resistance in vitro when it is exposed to the drug for short periods of time. Therefore, the majority of resistant isolates analyzed in this study were selected from plates that did not contain FLC, thus reducing the possibility of having induced FLC resistance in vitro during the initial processing and culturing of clinical samples (23).

Since evaluation of molecular mechanisms of resistance requires the use of matched sets of susceptible and resistant isolates, DNA-typing techniques were used to assess the relatedness of FLC-resistant and FLC-susceptible isolates from both patients. According to the molecular typing results, highly related C. dubliniensis strains colonized the mouths of both patients, persisted over time, and became resistant to FLC upon repeated exposure to the drug. Although resistance to FLC was associated with decreases in susceptibilities to itraconazole, voriconazole, ravuconazole, and, to a lesser extent, posaconazole, all these drugs remained active against the strains of C. dubliniensis with decreased susceptibilities to FLC. All isolates remained susceptible to amphotericin B and caspofungin.

The most frequent molecular mechanism of resistance found was upregulation of efflux pumps. Thus, overexpression of MDR1 genes was detected in all isolates showing high levels of FLC resistance. Concomitant upregulation of the CDR and ERG11 genes was found in 40 and 60% of these isolates, respectively. However, no upregulation of efflux pumps or of ERG11 genes was found in two isolates with decreased FLC susceptibility from one patient. It has previously been postulated that the CDR genes in C. albicans appear to remove many azole drugs, while MDR1 appears to be specific to FLC (35, 46). Because of the presence of decreased susceptibilities to other azoles in isolates in which we have only detected overexpression of MDR1 genes, other mechanisms of resistance besides the ones described above, such as the presence of point mutations in the gene encoding the azole target enzyme (lanosterol 14α-demethylase), could also be implicated. For that reason the sequences of the ERG11 genes of the isolates were obtained. In the first place, it was necessary to identify the homolog of the C. albicans ERG11 gene in C. dubliniensis. We accomplished this by PCR with primers spanning the entire C. albicans ERG11 open reading frame. Subsequent sequencing of the amplicons indicated that the C. dubliniensis ERG11 gene encodes a protein highly similar to its counterpart in C. albicans. A total of 14 nucleotide changes (compared to the wild-type sequence) that led to 14 amino acid substitutions were found in the clinical isolates with decreased susceptibilities to FLC. Four of these mutations (F126L, G307, V437A, and G464S) have been also found in clinical isolates of C. albicans with decreased susceptibilities to FLC, and two of them (G464S and G307A) have been shown to affect the affinity of the enzyme for the azoles. Some point mutations were detected in susceptible isolates and are not likely to play a role in resistance but, rather, may be indicative of differences between strains, as has been described in the case of C. albicans (28, 36). Also, even though we used high-fidelity polymerase, the possibility still remains that some of the nucleotide changes detected in the present study may have been introduced during PCR amplification, although this is highly unlikely. Functional expression assays with S. cerevisiae for assessment of the link between the novel point mutations found in the resistant isolates and alterations in the affinity of the ERG11 protein for the azole derivatives are being performed in our laboratory.

While the most relevant mechanism of resistance observed in experiments with FLC-resistant derivatives generated in vitro was the upregulation of efflux pumps (24), in vivo FLC resistance in C. dubliniensis appears to be a more complex and multifactorial phenomenon, similar to the observations found in the case of C. albicans (17, 24). This difference may be of relevance when considering strategies for resistance modulation in the clinical setting.

The clinical significance of the emergence of FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis is unknown. One of the patients in this series did not have any clinical symptoms of OPC, even though the patient was colonized with FLC-resistant C. dubliniensis isolates for an extended period of time, while the second patient had a severe episode of mixed (C. albicans and C. dubliniensis) OPC that did not respond to high doses of FLC. However, both patients differed markedly in their immunological status and the HIV type 1 RNA levels in their plasma. While one patient was responding to HAART and had an undetectable viral load, the second one did not respond to antiretroviral therapy and had progressive AIDS. These observations confirm that, as has previously been found for C. albicans, the recovery of host immunity and the decline in HIV type 1 RNA levels that follow the use of HAART play critical roles in determining the clinical relevance of yeast colonization of the oral cavities of HIV-infected patients (7, 9, 45). In addition, in the second patient, C. dubliniensis was isolated in conjunction with FLC-resistant C. albicans, making it impossible to determine the pathogenic role played by C. dubliniensis alone.

In summary, we have performed a study to evaluate the molecular mechanisms of azole resistance in C. dubliniensis clinical isolates with high-level FLC resistance from two HIV-infected patients who presented with OPC while receiving treatment with FLC. The results obtained show that azole resistance in clinical isolates of C. dubliniensis is the result of a combination of different molecular mechanisms, with the predominant mechanism being the overexpression of efflux transporters (major facilitators and ABC transporters), alone or in combination with overexpression of and point mutations in the target enzyme, the cytochrome P-450 lanosterol 14 α-demethylase. Larger studies are needed to determine the impact of FLC resistance on the pathogenic role of C. dubliniensis in patients with OPC.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants 5 R01 DE11381-04A2 from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (to T.F.P). Additional support was provided by Public Health Service grant R29 AI42401 (to J.L.L.-R.), a Supplemental Postdoctoral Minority Fellowship Grant (to M.M.), Public Health Service grant M01-RR-01346 for the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center, and a grant from Pfizer, Inc. S.P. acknowledges the receipt of a NATO postdoctoral fellowship. Chromogenic medium was provided by CHROMagar Candida.

We thank the Fungus Testing Laboratory at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio for performing antifungal susceptibility testing; D. R. Soll for providing C. albicans reference strain 3153A and the Ca3 and Cd25 probes; T. C. White for providing the plasmids containing the ERG11, CDR, and MDR1 sequences; D. Sanglard for providing plasmids containing the CDR1 and CDR2 sequences; and J. R. Naglik for C. dubliniensis type strain NCPF 3949.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boscot, P. E., and G. H. Grant. 1994. Modelying cytochrome P450 14α-demethylase (Candida albicans) from P450cam. J. Mol. Graphics 12:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandt, M. E., L. H. Harrison, M. Pass, A. N. Sofair, S. Huie, R. K. Li, C. J. Morrison, and D. W. Warnock. 2000. Candida dubliniensis fungemia: the first four cases in North America. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:46-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown, D. M., M. A. Jabra-Rizk, W. A. Falker, A. A. Baqui, and T. F. Meiller. 2000. Identification of Candida dublinienis in a study of HIV-seropositive pediatric dental patients. Pediatr. Dent. 22:234-238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman, D., D. Sullivan, B. Harrington, K. Haynes, M. Henman, D. Shanley, D. Bennett, G. Moran, C. McCreary, and L. O'Neill. 1997. Molecular and phenotypic analysis of Candida dubliniensis: a recent identified species linked with oral candidosis in HIV-infected and AIDS patients. Oral Dis. 1:96-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman, D. C., D. J. Sullivan, D. E. Bennett, G. P. Moran, H. J. Barry, and D. B. Shanley. 1997. Candidiasis: the emergence of a novel species, Candida dubliniensis. AIDS 11:557-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman, D. C., M. G. Rinaldi, K. A. Haynes, J. H. Rex, R. C. Summerbell, E. J. Anaissie, A. Li, and D. J. Sullivan. 1998. Importance of other species of Candida albicans as opportunistic pathogens. Med. Mycol. 1:156-165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Detels, R., A. Munoz, G. McFarlane, and Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study Investigators. 1998. Effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy on time to AIDS and death in men with known HIV infection duration. JAMA 280:1497-1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilfillan, G. D., D. J. Sullivan, K. Haynes, T. Parkinson, D. C. Coleman, and N. A. R. Gow. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: phylogeny and putative virulence factors. Microbiology 144:829-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottfredsson, M., G. M. Cox, O. S. Indridason, G. M. de Almeida, A. E. Heald, and J. R. Perfect. 1999. Association of plasma levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA and oropharyngeal Candida colonization. J. Infect. Dis. 180:534-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jabra-Rizk, M. A., A. A. M. Baqui, J. I. Kelley, W. A. Falkler, W. G. Merz, and T. F. Meiller. 1999. Identification of Candida dubliniensis in a prospective study of patients in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:321-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji, H., W. Zhang, Y. Zhou, M. Zhang, J. Zhu, Y. Song, J. Lu, and J. Zhu. 2000. A three-dimensional model of lanosterol 14α-demethylase of Candida albicans and its interaction with azole antifungals. J. Med. Chem. 43:2493-2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joly, S., C. Pujol, M. Rysz, K. Vargas, and D. R. Soll. 1999. Development and characterization of complex DNA fingerprinting probes for the infectious yeast Candida dubliniensis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamei, K., M. J. McCullough, and D. A. Stevens. 2000. Initial case of Candida dubliniensis infection from Asia: non-mucosal infection. Med. Mycol. 38:81-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirkpatrick, W. R., S. G. Revankar, R. K. McAtee, J. L. Lopez-Ribot, A. W. Fothergill, D. I. McCarthy, S. E. Sanche, R. A. Cantu, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Detection of Candida dubliniensis in oropharyngeal samples from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in North America by primary CHROMagar Candida screening and susceptibility testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3007-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai, M. H., and D. R. Kirsch. 1989. Nucleotide sequence of cytochrome P450 LIA1 (lanosterol 14α-demethylase) from Candida albicans. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:804.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Löffler, J., S. L. Kelly, H. Hebart, U. Schumacher, C. Lass-Flörl, and H. Einsele. 1997. Molecular analysis of cyp51 from fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 151:263-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lopez-Ribot, J. L., R. K. McAtee, L. N. Lee, W. R. Kirkpatrick, T. C. White, D. Sanglard, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2932-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manavathu, E. K., S. Kallakuri, M. T. Arganoza, and J. A. Vazquez. 1999. Amino acid variations of cytochrome P-450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51A1) from fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 16:198-203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marichal, P., L. Koymans, S. Willemsens, D. Bellens, P. Verhasselt, W. Luyten, M. Borges, F. C. Ramaekers, F. C. Odds, and H. Vanden Bossche. 1999. Contribution of mutations in the cytochrome P450 14α-demethylase (Erg11, Cyp51p) to azole resistance in Candida albicans. Microbiology 145:2701-2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCullough, M. J., K. V. Clemons, and D. A. Stevens. 1999. Molecular and phenotypic characterization of genotypic Candida albicans subgroups and comparison with Candida dubliniensis and Candida stellatoidea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:417-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meiller, T. F., M. A. Jabra-Rizk, A. A. Baqui, J. I. Kelley, V. I. Meeks, W. G. Merz, and W. A. Falkler. 1999. Oral Candida dubliniensis as a clinically important species in HIV-seropositive patients in the United States. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 88:573-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meis, J. F. G., M. Ruhnke, B. E. De Pauw, F. C. Odds, W. Siegert, and P. E. Verweij. 1999. Candida dubliniensis candidemia with chemotherapy-induced neutropenia and bone marrow transplantation. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 5:150-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moran, G. P., D. J. Sullivan, M. C. Henman, C. E. McReary, B. J. Harrington, D. B. Shanley, and D. C. Coleman. 1997. Antifungal drug susceptibilities of oral Candida dubliniensis isolates from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected and non-HIV-infected subjects and generation of stable fluconazole-resistant derivatives in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:617-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran, G. P., D. Sanglard, S. M. Donnelly, D. B. Shanley, D. J. Sullivan, and D. C. Coleman. 1998. Identification and expression of multidrug transporters responsible for fluconazole resistance in Candida dubliniensis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1819-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Committee for Clinical and Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical and Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 26.Odds, F. C., L. Van Nuffel, and G. Dams. 1998. Prevalence of Candida dubliniensis isolates in a yeast stock collection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2869-2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patterson, T. F., S. G. Revankar, W. R. Kirkpatrick, O. P. Dib, A. W. Fothergill, S. W. Redding, D. A. Sutton, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1996. Simple method for detecting fluconazole-resistant yeasts with chromogenic agar. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1794-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perea, S., J. L. López-Ribot, R. K. McAtee, W. R. Kirkpatrick, R. A. Santillan, D. Calabrese, D. Sanglard, and T. F. Patterson. 2001. Prevalence of molecular mechanisms of resistance to azole antifugal agents in Candida albicans isolates displaying high-level fluconazole resistance from HIV-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2674-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pfaller, M. A., S. A. Messer, S. Gee, S. Joly, C. Pujol, D. J. Sullivan, D. C. Coleman, and D. R. Soll. 1999. In vitro susceptibilities of Candida dubliniensis isolates tested against the new triazole and echinocandin antifungal agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:870-872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polacheck, I., J. Strahilevitz, D. Sullivan, S. Donnelly, I. F. Salkin, and D. C. Coleman. 2000. Recovery of Candida dubliniensis from non-human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in Israel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:170-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Revankar, S. G., O. P. Dib, R. W. Kirkpatrick, R. K. McAtee, A. W. Fothergill, M. G. Rinaldi, S. W. Redding, and T. F. Patterson. 1997. Clinical evaluation and microbiology of oropharyngeal infection due to fluconazole-resistant Candida in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 26:960-963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rex, J. H., M. A. Pfaller, J. N. Galgiani, M. S. Bartlett, A. Espinel-Ingroff, M. A. Ghannoum, M. Lancaster, F. C. Odds, M. G. Rinaldi, T. J. Walsh, and A. L. Berry. 1997. Development of interpretive breakpoints for antifungal susceptibility testing: conceptual framework and analysis of in vitro-in vivo correlation data for fluconazole, itraconazole, and Candida infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 24:235-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodero, L., M. Losso, C. Canteros, F. Hochenfellner, and G. Davel. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: 1st isolation in Argentina. Rev. Argent. Microbiol. 30:39-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruhnke, M., A. Schmidt-Westhausen, and J. Morschhäuser. 2000. Development of simultaneous resistance to fluconazole in Candida albicans and Candida dubliniensis in a patient with AIDS. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:291-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sanglard, D., K. Kuchler, F. Ischer, J. L. Pagani, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1995. Mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans isolates from AIDS patients involve specific multidrug transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2378-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, L. Koymans, and J. Bille. 1998. Amino acid substitutions in the cytochrome P-450 lanosterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51A1) from azole-resistant Candida albicans clinical isolates contribute to resistance to azole antifungal agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:241-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sano, A., M. M. Vilela, I. Takahashi, K. Fudushima, K. Takizawa, M. T. da Silva, J. Uno, K. Nishimura, and M. Miyaji. 2000. Isolation of Candida dubliniensis from the oral cavity of an HIV-positive child in Brazil. Nippon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi 41:177-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schimd, J., E. Voss, and D. R. Soll. 1990. Computer-assisted methods for assessing strain relatedness in Candida albicans by fingerprinting with the moderately repetitive sequence Ca3. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28:1236-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sebti, A., T. E. Kiehn, D. Perlin, V. Chatuverdi, M. Wong, A. Doney, S. Park, and K. A. Sepkowitz. 2001. Candida dubliniensis at a cancer center. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32:1034-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheehan, D. J., C. A. Hitchock, and C. M. Sibley. 1999. Current and emerging azole antifungal agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:40-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sullivan, D., K. Haynes, J. Bille, P. Boerlin, L. Rodero, S. Lloyd, M. Henman, and D. Coleman. 1997. Widespread geographic distribution of oral Candida dubliniensis strains in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:960-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan, D., and D. Coleman. 1998. Candida dubliniensis: characteristics and identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sullivan, D., and D. Coleman. 1997. Candida dubliniensis: an emerging opportunistic pathogen. Curr. Top. Med. Mycol. 8:15-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sullivan, D., T. H. Westerneng, K. A. Haynes, D. E. Bennet, and D. Coleman. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141:1507-1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valdez, H., B. M. Gripshover, R. A. Salata, and M. M. Lederman. 1998. Resolution of azole-resistant oropharyngeal candidiasis after initiation of potent combination antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 12:538.. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White, T. C., K. A. Marr, and R. A. Bowden. 1998. Clinical, cellular and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:382-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willis, A. M., W. A. Coulter, and D. J. Sullivan. 2000. Isolation of C. dubliniensis from insulin-using diabetes mellitus patients. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 29:86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]