Abstract

TEM-71, a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase from a Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolate, had an isoelectric point of 6.0 and a substrate profile showing preferential hydrolysis of cefotaxime over ceftazidime. It differed from TEM-1 by two substitutions, Gly238Ser and Glu240Lys, and was under the control of the strong P4 promoter.

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are enzymes that confer resistance to oxyimino-β-lactams such as cefotaxime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, and the monobactam aztreonam but not to cephamycins or carbapenems (5). ESBLs, which are predominantly derivatives of plasmid-mediated TEM or SHV β-lactamases, arise through mutations that introduce one or more amino acid substitutions that alter the configuration or binding properties of the active site, resulting in an expansion of the substrate range of the enzymes (G. A. Jacoby and K. Bush, website [http://www.lahey.org/studies/webt.htm]) (3, 5). ESBL-producing clinical isolates are frequently associated with nosocomial outbreaks (9, 21), with production detected most commonly in Klebsiella pneumoniae (8, 17) in addition to other members of the Enterobacteriaceae family (8) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (19). Novel ESBLs continue to be reported at an alarming rate (Jacoby and Bush, website) (3). Here, we describe another novel ESBL, designated TEM-71, produced by a clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae obtained from the blood of a patient in San Antonio, Tex., in 1994.

The susceptibility of K. pneumoniae 3635 to selected antimicrobial agents was determined by broth microdilution with cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) according to National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS) methods (20).

The antimicrobial agents used for susceptibility testing or kinetic studies were in some cases obtained from different sources. Amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cephaloridine, penicillin G, and piperacillin were from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.); aztreonam was from Bristol-Myers Squibb (Princeton, N.J.) and ICN Biomedicals, Inc. (Aurora, Ohio); cefepime was from Bristol-Myers Squibb; clavulanic acid was from GlaxoSmithKline (Collegeville, Pa.) and U.S. Pharmacopeia (Rockville, Md.); cefpodoxime was from Pharmacia & Upjohn (Kalamazoo, Mich.); ceftazidime was from Eli Lilly (Indianapolis, Ind.) and U.S. Pharmacopeia; cefoxitin and imipenem were from Merck (Rahway, N.J.); and tazobactam was from Wyeth-Ayerst Research (Pearl River, N.Y.).

Isoelectric focusing was performed as previously described (22), and the isoelectric point (pI) of the enzyme was determined in reference to TEM-1 (pI, 5.4), TEM-2 (pI, 5.6), TEM-3 (pI, 6.3), and SHV-3 (pI, 7.0).

Plasmid DNA was prepared by using a Qiagen plasmid midi kit (Qiagen, Chatsworth, Calif.) as previously described (22). The plasmids were separated vertically in a 0.9% agarose gel prepared with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and electrophoresed first at 40 V for 50 min and then at 120 V for 4 h.

Conjugal transfer of β-lactam resistance plasmids was performed as previously described (13). A spontaneous mutant of Escherichia coli J53 (F− met pro) resistant to 250 μg of sodium azide per ml was used as a recipient in resistance transfer studies (13).

Hybridization studies were performed as described previously (22). DNA transferred from agarose gels to positively charged nylon membranes (Zeta-Probe; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was hybridized with a 351-bp digoxigenin-labeled blaTEM DNA probe (22).

A 1,082-bp PCR product that included both the blaTEM-71 structural gene and its upstream regulatory region was amplified from both K. pneumoniae 3635 and its transconjugant with oligonucleotide primers (18) and concentrations of PCR reactants (22) as previously described. Cycling parameters for the amplification of the blaTEM gene included a 5-min denaturation at 96°C followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (96°C for 1 min), annealing (55°C for 1 min), and extension (72°C for 1 min) and ending with a final extension period of 72°C for 10 min. A 351-bp digoxigenin-labeled blaTEM probe was prepared under the same conditions, but an alternate deoxynucleoside triphosphate mixture containing substituted nucleosides was used (22).

The DNA sequences of both strands of the blaTEM-71 gene in K. pneumoniae 3635 and its E. coli transconjugant J53 (pMG259) were determined from purified PCR products (QIAquick spin columns; Qiagen) by using previously described oligonucleotides (18, 23). Purified pMG259 was used as a template to confirm and complete the blaTEM-71 sequence, particularly outside of the coding region of the gene.

The cycle sequencing reactions, purification of products, and analysis of data were performed as previously described (22). The DNA sequences of the leading and lagging strands were determined by using products of independent PCRs. DNA sequencing data were analyzed with DNASIS for Windows (Hitachi Software Genetic Systems, San Francisco, Calif.).

Transconjugant E. coli J53 (pMG259), the source of the TEM-71 enzyme, was grown overnight at 37°C in 2 liters of Trypticase soy broth supplemented with 200 μg of ampicillin/ml. The enzyme was purified for kinetic analysis as previously described (22). The enzyme for kcat determination was further purified by anion-exchange chromatography through a HiTrap Q column (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) in 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5). This preparation was 35% pure and unstable except in the presence of 10% glycerol. The purified enzyme focused as a single β-lactamase with a pI of 6.0. The protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Kinetic studies to determine Km and Vmax values were performed as previously described (22). The inhibition of hydrolysis was measured after the addition of 985 μl of cephaloridine (100 μM) to 5 μl of enzyme preincubated for 5 min with the inhibitor in 10 μl of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) at 25°C (4). The 50% inhibitory concentrations were determined graphically (4).

Based on NCCLS interpretive criteria for non-ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae (20), K. pneumoniae 3635 was resistant to ampicillin, cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, and piperacillin, intermediate to aztreonam, and susceptible to amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefepime, cefotaxime, cefoxitin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, and piperacillin-tazobactam (Table 1). Reductions in the MICs of aztreonam, cefotaxime, cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, and ceftriaxone by three or more twofold dilutions in the presence of clavulanic acid were indicative of ESBL production (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

MICs of selected antimicrobial agents for various strainsa

| Antimicrobial agent | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| K. pneumoniae 3635 | E. coli J53 | E. coli J53 (pMG259) | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanateb | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Ampicillin | >64 | 8 | >64 |

| Aztreonam | 16 | 0.12 | >64 |

| Aztreonam-clavulanatec | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| Cefepime | 1 | 0.06 | 2 |

| Cefotaxime | 8 | 0.25 | 16 |

| Cefotaxime-clavulanatec | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Cefoxitin | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Cefpodoxime | 32 | 2 | 128 |

| Cefpodoxime-clavulanatec | 0.12 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Ceftazidime | 32 | 0.25 | 128 |

| Ceftazidime-clavulanatec | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.25 |

| Ceftriaxone | 8 | 0.25 | 32 |

| Ceftriaxone-clavulanatec | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Imipenem | ≤1 | ≤1 | ≤1 |

| Piperacillin | >128 | ≤2 | >128 |

| Piperacillin-tazobactamd | 4 | 2 | ≤1 |

Quality control organisms for MIC determinations were Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212, E. coli ATCC 25922, E. coli ATCC 35218, K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603, P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213.

2:1 concentration ratio.

Clavulanic acid was used at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml.

Tazobactam was used at a final concentration of 4 μg/ml.

K. pneumoniae 3635 contained a β-lactamase with a pI of 6.0 and a second β-lactamase with a pI of 7.6 (data not shown). The latter was identified by DNA sequence analysis as SHV-1. Strain 3635 carried two plasmids with molecular sizes of approximately 101 and 71 kb. Resistance to ceftazidime was associated with the 71-kb plasmid, which was transferable to E. coli J53 via conjugation. The blaTEM gene was localized to the 71-kb plasmid with a blaTEM-specific digoxigenin-labeled probe (data not shown). The transconjugant E. coli J53 (pMG259) expressed a single β-lactamase with a pI of 6.0 and was resistant to ampicillin, aztreonam, cefpodoxime, ceftazidime, and piperacillin (Table 1).

The MICs of aztreonam and several of the extended-spectrum cephalosporins were consistently higher for the transconjugant E. coli J53 (pMG259) than for K. pneumoniae 3635 (Table 1). Quantitative studies showed that the higher MICs for the transconjugant were due to an increase in β-lactamase activity, possibly suggesting better expression in E. coli (data not shown).

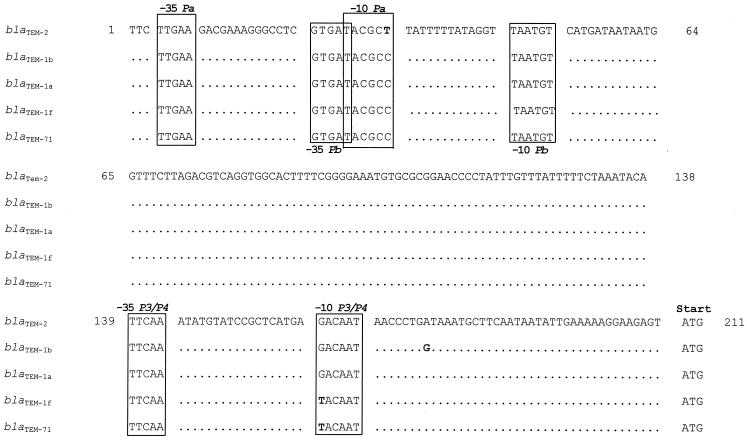

A comparison of nucleotide mutations and inferred amino acid substitutions at key sites within the regulatory and coding regions of blaTEM-71, blaTEM-1a (25), blaTEM-1b (10), blaTEM-1c (11), blaTEM-1d (15, 16), blaTEM-1e (15, 16), blaTEM-1f (15, 16), and blaTEM-2 (10) is shown in Table 2. The DNA sequence of blaTEM-71 revealed that it could be a derivative of the recently described blaTEM-1f gene (15, 16). Although both blaTEM-71 and blaTEM-1f possess all of the silent mutations found in blaTEM-2 (10) compared to the blaTEM-1a gene (25), neither gene encodes the Gln39Lys substitution characteristic of the TEM-2 enzyme. Furthermore, the P4 promoter (containing a G162→T transversion which is located at position 1 of the −10 consensus Pribnow box sequence of the P3 promoter) (11, 24) (Fig. 1) was found upstream of both blaTEM-71 and blaTEM-1f (15, 16) instead of the overlapping Pa and Pb promoters located upstream from the blaTEM-2 gene (7, 10) (Table 2 and Fig. 1). The P4 promoter has been shown to result in hyperproduction of TEM-1 (24).

TABLE 2.

Nucleotide mutations and amino acid substitutions among selected blaTEM genes and corresponding enzymesa

| Gene (promoter) | Nucleotide (amino acid) at indicated positionb

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32 | 162 | 175 | 226 (6) | 317 (39) | 346 (48) | 436 (78) | 604 (134) | 682 (160) | 913 (237) | 914 (238) | 917 (240) | 925 (242) | Reference | |

| blaTEM-1a (P3) | C | G | A | C | C (Gln) | A | C | G | T | C | G (Gly) | G (Glu) | G | 25 |

| blaTEM-1b (P3) | G | T | T | T | 10 | |||||||||

| blaTEM-1c (P3) | T | 11 | ||||||||||||

| blaTEM-1d (P3) | T | T | 15, 16 | |||||||||||

| blaTEM-1e (P3) | G | T | G | T | T | 15, 16 | ||||||||

| blaTEM-1f (P4) | T | G | T | C | A | 15, 16 | ||||||||

| blaTEM-71 (P4) | T | G | T | C | A (Ser) | A (Lys) | A | This study | ||||||

| blaTEM-2 (Pa/Pb) | T | A (Lys) | G | T | C | A | 10 | |||||||

FIG. 1.

Comparison of promoter sequences of the β-lactamase genes blaTEM-2 (10), blaTEM-1b (10), blaTEM-1a (25), blaTEM-1f (15, 16), and blaTEM-71. The differences are shown in boldface. The −35 and −10 regions of Pa, Pb, and P3/P4 are boxed. The start codon is indicated. The nucleotide positions are numbered according to Sutcliffe (25).

The amino acid sequence inferred from the DNA sequence of blaTEM-71 revealed two substitutions compared to the TEM-1 enzyme (25): Gly238Ser and Glu240Lys, both thought to play key roles in the hydrolysis of oxyimino-β-lactams and the monobactam aztreonam (6, 14, 26). TEM-71 is the first natural variant of TEM β-lactamase that contains both a serine at position 238 and a lysine at position 240 unaccompanied by additional substitutions (Jacoby and Bush, website).

TEM-48 and TEM-49 are two enzymes that contain both the Gly238Ser and Glu240Lys substitutions in addition to other mutations (9). A comparison of the DNA sequences of the blaTEM-48 and blaTEM-49 genes with the sequence of blaTEM-71 suggests the possibility of a close relationship. The three genes differ within the coding region by only three mutations: C→T transitions at nucleotide positions 263 (Leu21Phe substitution in TEM-48 and TEM-49) and 990 (Thr265Met substitution in TEM-48 and TEM-49) and an A→G transition at position 998 (Ser268Gly substitution in TEM-49) (9). The blaTEM-48, blaTEM-49, and blaTEM-71 genes share G→A transitions at nucleotide positions 914 (Gly238Ser substitution in TEM-48, TEM-49, and TEM-71) and 917 (Glu240Lys substitution in TEM-48, TEM-49, and TEM-71) as well as four silent mutations (A346→G, C436→T, T682→C, and G925→A) (9) (Table 2) in their sequences compared to the DNA sequence of blaTEM-1a (25). Whether these genes also share similar promoters is not known, since the nucleotide sequences reported for blaTEM-48 and blaTEM-49 did not include their upstream regulatory regions (9).

The simultaneous presence of the Gly238Ser and Glu240Lys substitutions is more typically observed within the SHV family of enzymes than in variants of TEM β-lactamase (Jacoby and Bush, website) (3). Included among these is SHV-5, which, like TEM-71, contains the mutations at positions 238 and 240 without additional substitutions (2).

The kinetic parameters for TEM-71 are consistent with those of an ESBL (Table 3). The highest Vmax values were for cefotaxime and cephaloridine and were approximately twice the rate for penicillin and 10-fold greater than that for ceftazidime. Both extended-spectrum cephalosporins were hydrolyzed at relative rates at least 3 orders of magnitude higher than by TEM-1 (5). The lowest hydrolysis rate of the five substrates tested was for aztreonam.

TABLE 3.

Kinetic properties of purified TEM-71 β-lactamase

| Substrate | Mean Vmaxa ± SD | Relative Vmax (%) | Mean Km ± SD (μM) | Relative Vmax/Km (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G | 0.49 ± 0.004 | 100 | 2.1 ± 0.14 | 100 |

| Cephaloridineb | 0.87 ± 0.06 | 180 | 8.3 ± 1.2 | 43 |

| Ceftazidime | 0.11 ± 0.005 | 22 | 100 ± 20 | 0.4 |

| Cefotaxime | 1.1 ± 0.05 | 220 | 73 ± 5.0 | 6.0 |

| Aztreonamc | <0.03 | <6 | NDd | ND |

Nanomoles of substrate hydrolyzed per minute per milligram of protein.

kcat for cephaloridine was 13 s−1.

Values based on estimated Vmax.

ND, not determined. The rate of hydrolysis of aztreonam was too low to obtain an accurate Km value.

The TEM-71 enzyme had strong binding for both penicillin and cephaloridine, based on Km values of 2.1 and 8.3 μM, respectively (Table 3). The relative hydrolytic efficiencies, measured by Vmax/Km, revealed that penicillin was hydrolyzed at least twice as efficiently as cephaloridine and approximately 17 and 250 times better than cefotaxime and ceftazidime, respectively. Cefotaxime was hydrolyzed 15 times as efficiently as ceftazidime. Although the rates of hydrolysis of ceftazidime and aztreonam compared to that of cefotaxime were lower than expected given their MICs, this relationship has been reported in the characterization of other β-lactamases as well (22, 28).

Although the substitutions in SHV-5 and TEM-71 are analogous, their kinetic properties appear to differ (12). Cefotaxime is hydrolyzed approximately 2 times more efficiently than ceftazidime by SHV-5 as opposed to 15 times more efficiently by TEM-71. However, both enzymes exhibited a preference for cefotaxime hydrolysis over ceftazidime. Notably, neither enzyme hydrolyzed aztreonam at a measurable rate, in contrast to most TEM- and SHV-derived ESBLs.

Clavulanic acid and tazobactam both inhibited the TEM-71 β-lactamase, with 50% inhibitory concentrations of 6.1 and 7.8 nM, respectively (data not shown). As expected for serine-based β-lactamases, no inhibition was observed when the enzyme was assayed with 10 mM EDTA at pH 7.0.

In summary, blaTEM-71, reported here from K. pneumoniae but recently also discovered in an E. coli blood isolate (27), is an example of the ongoing evolution of ESBL genes linking mutations that expand the substrate-binding and hydrolytic properties of the enzymes with strong promoters that enhance gene expression.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of blaTEM-71 reported in this study will appear under the GenBank accession number AF203816.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jana Swenson, Christine Steward, and Portia Williams for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. We also thank Linda Weigel for reviewing the manuscript and for helpful discussions and Colleen Gownley for purification of the kcat fraction of the enzyme.

G.A.J. was supported in part by a Merit Review award from the Veterans Affairs-Department of Defense Collaborative Research Program on Mechanisms of Emerging Pathogens.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambler, R. P., A. F. W. Coulson, J.-M. Frère, J.-M. Ghuysen, B. Joris, M. Forsman, R. C. Levesque, G. Tiraby, and S. G. Waley. 1991. A standard numbering scheme for the class A β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 276:269-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billot-Klein, D., L. Gutmann, and E. Collatz. 1990. Nucleotide sequence of the SHV-5 β-lactamase gene of a Klebsiella pneumoniae plasmid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2439-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford, P. A. 2001. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14:933-951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush, K., and R. B. Sykes. 1986. Methodology for the study of β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 30:6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush, K., G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros. 1995. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cantu, C., III, W. Huang, and T. Palzkill. 1996. Selection and characterization of amino acid substitutions at residues 237-240 of TEM-1 β-lactamase with altered substrate specificity for aztreonam and ceftazidime. J. Biol. Chem. 271:22538-22545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, S.-T., and R. C. Clowes. 1984. Two improved promoter sequences for the β-lactamase expression arising from a single base-pair substitution. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:3219-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coudron, P. E., E. S. Moland, and C. C. Sanders. 1997. Occurrence and detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae at a veterans medical center: seek and you may find. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2593-2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gniadkowski, M., I. Schneider, R. Jungwirth, W. Hryniewicz, and A. Bauernfeind. 1998. Ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from three Polish hospitals: identification of three novel TEM- and SHV-5-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:514-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goussard, S., and P. Courvalin. 1991. Sequence of the genes blaT-1B and blaT-2. Gene 102:71-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goussard, S., and P. Courvalin. 1999. Updated sequence information for TEM β-lactamase genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:367-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutmann, L., B. Ferré, F. W. Goldstein, N. Rizk, E. Pinto-Schuster, J. F. Acar, and E. Collatz. 1989. SHV-5, a novel SHV-type β-lactamase that hydrolyzes broad-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:951-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacoby, G. A., and P. Han. 1996. Detection of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:908-911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knox, J. R. 1995. Extended-spectrum and inhibitor-resistant TEM-type β-lactamases: mutations, specificity, and three-dimensional structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2593-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leflon-Guibout, V., B. Heym, and M.-H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2000. Updated sequence information and proposed nomenclature for blaTEM genes and their promoters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3232-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leflon-Guibout, V., V. Speldooren, B. Heym, and M.-H. Nicolas-Chanoine. 2000. Epidemiological survey of amoxicillin-clavulanate resistance and corresponding molecular mechanisms in Escherichia coli isolates in France: new genetic features of blaTEM genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2709-2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mabilat, C., and P. Courvalin. 1990. Development of “oligotyping” for characterization and molecular epidemiology of TEM β-lactamases in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:2210-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mabilat, C., and S. Goussard. 1993. PCR detection and identification of genes for extended-spectrum β-lactamases, p. 553-559. In D. H. Persing, T. F. Smith, F. C. Tenover, and T. J. White (ed.), Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 19.Mugnier, P., P. Dubrous, I. Casin, G. Arlet, and E. Collatz. 1996. A TEM-derived extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2488-2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 5th ed. Approved standard M7-A5. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 21.Peña, C., M. Pujol, C. Ardanuy, A. Ricart, R. Pallares, J. Liñares, J. Ariza, and F. Gudiol. 1998. Epidemiology and successful control of a large outbreak due to Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:53-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasheed, J. K., G. J. Anderson, H. Yigit, A. M. Queenan, A. Doménech-Sánchez, J. M. Swenson, J. W. Biddle, M. J. Ferraro, G. A. Jacoby, and F. C. Tenover. 2000. Characterization of the extended-spectrum β-lactamase reference strain, Klebsiella pneumoniae K6 (ATCC 700603), which produces the novel enzyme SHV-18. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2382-2388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasheed, J. K., C. Jay, B. Metchock, F. Berkowitz, L. Weigel, J. Crellin, C. Steward, B. Hill, A. A. Medeiros, and F. C. Tenover. 1997. Evolution of extended-spectrum β-lactam resistance (SHV-8) in a strain of Escherichia coli during multiple episodes of bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:647-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siu, L. K., P. L. Ho, K. Y. Yuen, S. S. Y. Wong, and P. Y. Chau. 1997. Transferable hyperproduction of TEM-1 β-lactamase in Shigella flexneri due to a point mutation in the Pribnow box. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:468-470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sutcliffe, J. G. 1978. Nucleotide sequence of the ampicillin resistance gene of Escherichia coli plasmid pBR322. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 75:3737-3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Venkatachalam, K. V., W. Huang, M. LaRocco, and T. Palzkill. 1994. Characterization of TEM-1 β-lactamase mutants from positions 238 to 241 with increased catalytic efficiency for ceftazidime. J. Biol. Chem. 269:23444-23450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong-Beringer, A., J. Hindler, M. Loeloff, A. M. Queenan, N. Lee, D. A. Pegues, J. P. Quinn, and K. Bush. 2002. Molecular correlation for the treatment outcomes in bloodstream infections caused by Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae with reduced susceptibility to ceftazidime. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34: 135-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan, M., L. M. C. Hall, P. H. M. Savelkoul, C. M. J. E. Vandenbroucke-Grauls, and D. M. Livermore. 2000. SHV-13, a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase, in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from patients in an intensive care unit in Amsterdam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1081-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]