Abstract

The objective of the present trial was to compare the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of moxifloxacin (400 mg) given intravenously (i.v.) once daily followed by oral moxifloxacin (400 mg) for 7 to 14 days with the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of co-amoxiclav (1.2 g) administered by i.v. infusion three times a day followed by oral co-amoxiclav (625 mg) three times a day, with or without clarithromycin (500 mg) twice daily (i.v. or orally), for 7 to 14 days in adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia requiring initial parenteral therapy. A total of 628 patients were enrolled and assessed by evaluation of their clinical and bacteriological responses 5 to 7 days and 21 to 28 days after administration of the last dose of study medication. Although the trial was designed, on the basis of predefined outcomes, to demonstrate the equivalence of the two regimens, the results showed statistically significant higher clinical success rates (for moxifloxacin, 93.4%, and for comparator regimen, 85.4%; difference [Δ], 8.05%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.91 to 13.19%; P = 0.004) and bacteriological success rates (for moxifloxacin, 93.7%, and for comparator regimen, 81.7%; Δ, 12.06%; 95% CI, 1.21 to 22.91%) for patients treated with moxifloxacin. This superiority was seen irrespective of the severity of the pneumonia and whether or not the combination therapy included a macrolide. The time to resolution of fever was also statistically significantly faster for patients who received moxifloxacin (median time, 2 versus 3 days), and the duration of hospital admission was approximately 1 day less for patients who received moxifloxacin. The treatment was converted to oral therapy immediately after the initial mandatory 3-day period of i.v. administration for a larger proportion of patients in the moxifloxacin group than patients in the comparator group (151 [50.2%] versus 57 [17.8%] patients). There were fewer deaths (9 [3.0%] versus 17 [5.3%]) and fewer serious adverse events (38 [12.6%] versus 53 [16.5%]) in the moxifloxacin group than in the comparator group. The rates of drug-related adverse events were comparable in both groups (38.9% in each treatment group). The overall incidence of laboratory abnormalities was similar in both groups. Thus, it is concluded that monotherapy with moxifloxacin is superior to that with a standard combination regimen of a β-lactam and a β-lactamase inhibitor, co-amoxiclav, with or without a macrolide, clarithromycin, in the treatment of patients with community-acquired pneumonia admitted to a hospital.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a common condition and continues to be an important cause of mortality. Each year in the United Kingdom approximately 50,000 people with CAP (3) are admitted to a hospital. Some 80% of cases are managed in the community, where the mortality rate is 1 to 2%. Among those patients admitted to a hospital, 5 to 10% will die, with the mortality rate rising to 50% among those requiring intensive care. In the United States, CAP is the sixth leading cause of death (13). The cost of treatment for CAP in the United Kingdom alone is estimated to be £440.7 million per year, with hospitalized patients accounting for as much as 96% of this cost (11). Consequently, there is growing pressure upon clinicians to reduce the number and duration of hospital admissions.

The importance of CAP as a major cause of morbidity and mortality together with its impact on health care resources is reflected in the plethora of published studies. Furthermore, there remain inconsistencies between national clinical guidelines; these reflect variations in the prevalence of target pathogens, drug resistance patterns, and clinical practice. Clinical trials designed to support the licensing of new agents generally limit any progress in our knowledge of disease management since they are designed to determine equivalence between the test and control regimens.

Moxifloxacin is a new fluoroquinolone antibiotic with increased activity against gram-positive organisms, notably Streptococcus pneumoniae, and acts by inhibiting bacterial topoisomerases II and IV. The objective of the trial reported here was to examine the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of moxifloxacin (400 mg) given intravenously (i.v.) once daily followed by oral moxifloxacin (400 mg) for 7 to 14 days for the treatment of CAP. This regimen was compared with co-amoxiclav (1.2 g) administered by i.v. infusion three times a day followed by oral co-amoxiclav (625 mg) three times a day, with or without clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily (i.v. or orally), for 7 to 14 days in adult patients requiring initial parenteral therapy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Male and female patients aged 18 years or over with radiological evidence of CAP (and who had been in a hospital for less than 48 h) were entered into the trial. To be included the patients were required to have a temperature ≥38.5°C or leukocytosis and at least one of the following clinical symptoms of pneumonia: cough, purulent sputum, dyspnea, rigors, pleuritic chest pain, or auscultatory findings. All patients required initial parenteral therapy, and approximately half had severe pneumonia, as defined by the criteria of the American Thoracic Society (16). To meet the definition of severe CAP the patients had to have at least one of the following: a respiratory rate of ≥30 breaths/min, hypoxemia with a partial oxygen pressure of ≤8 kPa (60 mm Hg), a need for mechanical ventilation, diastolic blood pressure ≤60 mm Hg, a chest X ray showing bilateral or multilobar involvement, or a requirement for treatment with vasopressors for more than 4 h.

Exclusion criteria included the presence of a coexisting disease considered likely to affect the outcome of the study (e.g., lung cancer, empyema, or severe cardiac failure) or a rapidly fatal underlying disease; known prolongation of the QT interval or the use of class IA or class III antiarrhythmics; known hypersensitivity to fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, or macrolides; aspiration pneumonia; and pretreatment with systemic antibacterial agents for more than 24 h prior to enrollment in the study. Patients who had clearly failed previous antibacterial therapy, which they had received for at least 72 h for the current pneumonia episode, could be enrolled unless the antibacterial regimen contained a fluoroquinolone or a β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor combination.

Patients were recruited by 65 centers in 10 countries: Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Israel, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, Russia, and the United Kingdom. The study was conducted in accordance with the Internal Conference on Harmonization Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (1997).

Study design.

This multinational, multicenter study used a randomized, open, parallel group design to compare sequential i.v. and oral moxifloxacin treatment with that of a standard antibiotic regimen, sequential i.v. and oral co-amoxiclav with or without clarithromycin, in patients with CAP who, in the judgment of the investigator, required initial parenteral therapy.

Randomization was performed locally on the basis of a centrally established code. Prior to randomization to one of the two parallel treatment groups, the patients were stratified into two groups according to disease severity. Patients were to be treated for a period of no less than 7 days and for a maximum of 14 days. After a minimum of 3 days patients could be converted from i.v. to oral therapy if they had demonstrated clinical improvement, were able to tolerate the oral intake of medication, and had no gastrointestinal condition likely to impair absorption.

The patients in the moxifloxacin group were initially administered 400 mg of moxifloxacin in 250 ml of 0.8% saline as an i.v. infusion over 60 min once daily. Thereafter, moxifloxacin was given as a 400-mg tablet once a day.

Patients receiving the comparator regimen were given 1.2 g of co-amoxiclav in 20 ml of water as an i.v. injection over 3 to 4 min three times a day. After conversion to oral therapy, co-amoxiclav was administered three times a day as 625-mg tablets. If the investigator considered that the addition of clarithromycin was indicated, in order to cover the possibility that the pathogens might be atypical organisms, it could be given initially as either an i.v. or an oral dose. Clarithromycin was supplied as 500 mg of sterile powder for reconstitution in 10 ml of sterile water and was infused in 250 ml of a suitable diluent over 60 min twice daily. Oral clarithromycin was administered as a 500-mg tablet twice a day.

Clinical, bacteriological, and laboratory examinations were performed pretreatment, 5 to 7 days after the end of therapy (the test-of-cure [TOC] visit), and 21 to 28 days after the end of treatment. These included a Gram stain and culture of sputum, blood culture, blood for hematology and chemistry safety profiles, and serologic testing for Legionella pneumophila, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae (testing for the last organism was done only pretherapy and 21 to 28 days posttherapy). According to the study protocol, invasive techniques were not required to collect specimens for culture. Specific culture or antigen testing was not done to detect atypical pathogens. If a patient failed to respond to the study medication, the assessments were to be completed before and 5 to 7 days after the end of an alternative antibiotic therapy.

Vital signs, i.e., temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure, were monitored daily up to the time of the patient's discharge from the hospital or the end of treatment, whichever came first. Adverse events (including laboratory abnormalities) were assessed up to the TOC visit. Any adverse events present at that time were monitored until they resolved or stabilized. On day 3 of i.v. therapy, a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram was to be performed for all patients within 30 min after the end of the first infusion of moxifloxacin or co-amoxiclav with or without clarithromycin.

The primary efficacy variable was the clinical response 5 to 7 days after the end of the drug treatment period (determined at the TOC visit) in the valid-per-protocol (PP) population. The clinical responses were defined as “clinical cure,” which was the disappearance of acute signs and symptoms related to infection with no requirement for further antibiotic therapy; “clinical failure,” which was the failure to respond or and an insufficient response to the study drug that required a modification in antibacterial therapy or that resulted in death from the primary diagnosis; and “indeterminate,” which was a clinical response that could not be determined because of early discontinuation from the study or protocol violation. Secondary efficacy parameters included the time to resolution of fever, the bacteriological response 5 to 7 days after treatment, bacteriological and clinical responses 21 to 28 days posttreatment, the duration of i.v. therapy, and the duration of hospital admission.

Statistical analysis.

In accordance with the notes for guidance on the use of new antibacterial medicinal products of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (April 1997), the specified equivalence delta between the clinical success rates for the two treatment groups was 10%. With an estimated failure rate of 15%, α equal to 5% (two sided), β equal to 15%, and a 5% adjustment for the multicenter design, the Farrington Manning sample size calculation called for 312 patients to be enrolled in each treatment group.

Two types of analysis were performed for each efficacy variable: a PP analysis and an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

In order to be included in the primary efficacy analysis, patients had to have a diagnosis of CAP and a documented rate of compliance with receipt of the study medication of ≥80%. Study drugs were to have been given for a minimum of 48 h in the case of clinical failure or a full 5 days in the case of clinical cure. The patient could not have received any concomitant systemic antimicrobial agents except in cases of treatment failure. There were to be no protocol violations that might have influenced efficacy and no missing essential data such as the clinical assessment at the TOC visit.

The ITT analysis included those patients who had been randomized and who received at least one dose of study drug.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment group by using the mean, standard deviation, median, quartiles, and minima and maxima for quantitative data or frequency counts for categorical data. Treatment group comparability was established for both the PP and the ITT analyses. The valid-for-safety population was the same as that for the ITT analysis.

A two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the difference between success rates (the rate for the moxifloxacin group minus the rate for the comparator group) was calculated by using Mantel-Haenszel weights. Moxifloxacin was deemed to be not less effective than the comparator regimen if the lower limit of this CI was greater than −10%. In this analysis any clinical failures occurring before the TOC visit were counted as clinical failures at the TOC visit. Similarly, failures at the TOC visit were carried forward for the late follow-up analysis. Clinical success was defined as a clinical cure, and bacteriological success was defined as eradication or presumed eradication of the pathogen(s). The findings of the study not only supported the noninferiority hypothesis but also suggested superiority. Therefore, in accordance with the Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products points to consider, the exact probability associated with a test of superiority was calculated by using the continuity-adjusted chi-square test.

The time to resolution of fever was analyzed by using both the log rank test and the Wilcoxon test (since there was evidence of nonproportional hazards between the two treatment groups).

The safety of each treatment was described by summary statistics; no formal statistical analyses were performed. Treatment groups were compared with respect to the incidence rate of adverse events, laboratory data, and electrocardiographic findings.

RESULTS

Efficacy.

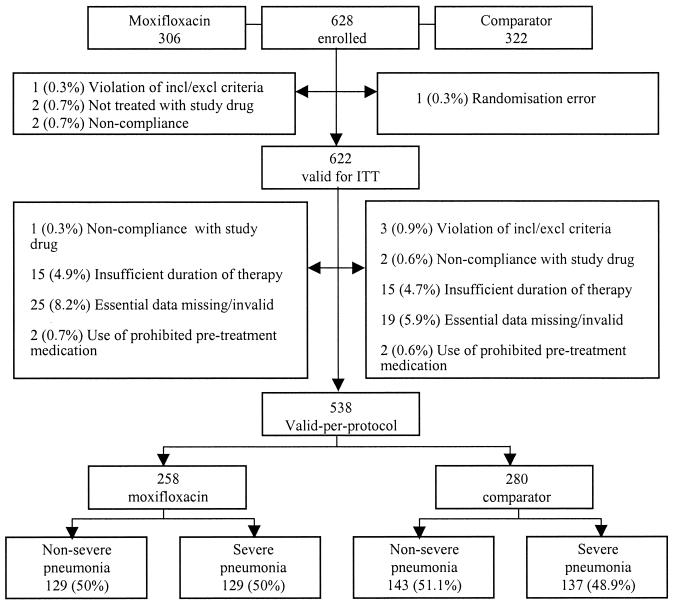

A total of 628 patients were enrolled in the trial, and 622 were valid for the ITT and safety analyses. More than half (n = 321) of the patients in the ITT and safety analyses had a diagnosis of severe CAP. There were 538 patients in the PP analysis. The trial population profile is depicted in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Trial population profile. Percentages are expressed as a fraction of the number of patients per treatment group. incl/exclu, inclusion/exclusion.

All study patients had signs and symptoms of CAP which was confirmed by chest radiography. The baseline characteristics of the patients included in the ITT analysis are summarized in Table 1, and testing for homogeneity showed that there was no imbalance between the two treatment groups. Similarly, the numbers of patients receiving antibiotics prior to entry into the trial and the numbers of patients with ≥72 h of prior antibiotic therapy were balanced between the two treatment groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients in ITT analysis

| Characteristic | Mean ± SD or incidence (no. [%] of patients) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Moxifloxacin group (n = 301) | Comparator group (n = 321) | |

| Age (yr) | 55.2 ± 20.6 | 55.9 ± 19.6 |

| Preexisting bronchopulmonary disease | 84 (27.9) | 92 (28.7) |

| Smokersa | 177 (58.8) | 196 (61.1) |

| Temp (°C) | 38.7 ± 0.9 | 38.8 ± 1.0 |

| Rigors or chills | 199 (66.1) | 205 (63.9) |

| Cough | 281 (93.4) | 295 (91.9) |

| Dyspnea | 244 (81.1) | 268 (83.5) |

| Respiratory rate (no. of breaths/min) | 24.4 ± 7.0 | 25 ± 7.1 |

| Pleuritic chest pain | 172 (57.1) | 187 (58.3) |

| Dullness to percussion | 130 (43.2) | 150 (46.7) |

| Rales or rhonchi | 258 (85.7) | 276 (86.0) |

| X ray | ||

| Unilateral infiltrate | 261 (86.7) | 262 (81.6) |

| Bilateral infiltrate | 53 (17.6) | 81 (25.2) |

| Pleural effusion | 43 (14.3) | 55 (17.1) |

| Previous antimicrobial therapy | 115 (38.2) | 112 (34.9) |

Includes previous smokers.

Bacterial cultures or serology were performed for a total of 326 (52%) patients. Not all patients were able to provide material for culture. There were 159 patients in the moxifloxacin group and 167 patients in the comparator group. Causative organisms were identified in 194 patients, giving an incidence of 59.5% (57.2% in patients in the moxifloxacin group and 61.7% in patients in the comparator group).

S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae were the most common organisms identified, accounting for 55.4 and 19.6% of all pathogens identified, respectively. Multiple pathogens were identified in 6.4% of patients. Atypical organisms (M. pneumoniae, C. pneumoniae, and L. pneumophila) were the causes of infections in 13.8% (45 of 326) of patients (infection was defined as a fourfold increase in the antibody titer between acute- and convalescent-phase sera). M. pneumoniae was the most frequent atypical organism identified. For five patients with positive serologies for atypical organisms, a causative bacterial organism(s) was also isolated from cultures of respiratory and/or blood specimens.

The microbiological susceptibilities of the most frequently isolated pathogens from pretreatment samples are presented in Table 2. The susceptibilities are presented as the MICs and the MICs at which 90% of the isolates tested are inhibited, as determined by the E-test methodology.

TABLE 2.

Pretherapy bacterial susceptibility, by source, for the most frequently isolated organisms (PP analysis)

| Infection, species, and antibiotic tested | No. of strains tested | MIC (mg/liter) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 90%a | Range | ||

| Respiratory | |||

| S. pneumoniae | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 38 | 0.19 | 0.032-0.470 |

| Clarithromycin | 37 | 1.00 | 0.016-256.00 |

| Co-amoxiclav | 37 | 0.25 | 0.016-4.000 |

| Penicillin | 37 | 0.75 | 0.006-2.000 |

| H. influenzae | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 20 | 0.32 | 0.006-0.470 |

| Clarithromycin | 18 | 16.00 | 0.016-24.000 |

| Co-amoxiclav | 19 | 8.00 | 0.023-256.00 |

| Penicillin | 9 | 3.00 | 0.064-3.000 |

| Blood | |||

| S. pneumoniae | |||

| Moxifloxacin | 18 | 0.25 | 0.047-0.250 |

| Clarithromycin | 15 | 256.00 | 0.016-256.00 |

| Co-amoxiclav | 18 | 1.00 | 0.016-1.000 |

| Penicillin | 17 | 1.50 | 0.004-2.000 |

90%, MIC at which 90% of isolates tested are inhibited, respectively.

Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of efficacy at the TOC visit and late follow-up visits for the population included in the PP analysis.

TABLE 3.

Analysis of efficacy for population in PP analysis

| Response | No. (%) of patients |

% Δ (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moxifloxacin group | Com- parator | ||

| Clinical cure at TOC visit (days 5-7 posttherapy) | 241 (93.4) | 239 (85.4) | 8.05a (2.91-13.19) |

| Clinical cure (days 21-28 posttherapy) | 216 (83.7) | 208 (74.3) | 9.40 (2.60-16.27) |

| Bacteriological successb at TOC visit (days 5 to 7 posttherapy) | 60 (93.7) | 58 (81.7) | 12.06 (1.21-22.91) |

| Bacteriological successb (days 21-28 posttherapy) | 54 (84.4) | 50 (70.4) | 14.0 (0.00-27.91) |

By test of superiority, P = 0.004.

Eradication and presumed eradication in microbiologically valid patients.

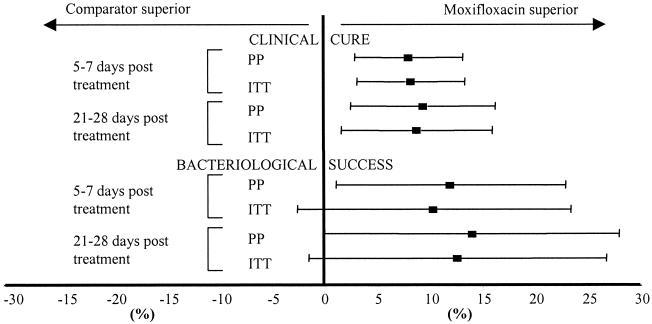

Moxifloxacin-treated patients had a significantly higher clinical cure rate, irrespective of the assessment time. The clinical cure rate at the TOC visit for the moxifloxacin group was 8.05% greater than that for the patients receiving the comparator regimen (95% CI, 2.91 to 13.19%). The clinical cure rate at the TOC visit for patients treated with moxifloxacin was also significantly superior to that for patients receiving the comparator regimen in the ITT analysis (difference [Δ] = 8.25%; 95% CI, 3.13 to 13.6%) and in the subgroup of patients valid for microbiological analysis. The higher rate of clinical cure seen among the patients treated with moxifloxacin in the PP analysis was irrespective of whether the patients on the comparator regimen were treated with co-amoxiclav alone (85%) or co-amoxiclav together with clarithromycin (85.6%). The continuity-adjusted P values (as determined by the chi-square test) for clinical response at the TOC assessment were 0.004 for the population in the PP analysis and 0.003 for the population in the ITT analysis (missing and indeterminate responses were dropped from the analyses).

The wider CIs for the point estimates of bacteriological success reflect the smaller patient numbers in the analyses. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with those for clinical cure, although statistical significance can be claimed only for the PP analysis at the TOC visit. The difference in bacterial success rates between moxifloxacin and the comparator groups at the TOC visit (5 to 7 days posttreatment) was 12% in favor of the moxifloxacin group. For the group of patients valid for microbiological analysis, the superiority was largely related to documented S. pneumoniae infections. The rate of bacteriological success for patients infected with penicillin-intermediate strains (MICs, ≥1.0 to <2.0 mg/liter) and penicillin-resistant strains (MICs, ≥2.0 mg/liter) of S. pneumoniae at days 5 to 7 posttreatment was significantly higher for the moxifloxacin group and was supported by the bacteriological evaluation at the late follow-up on days 21 to 28. Clinical cures were achieved in all moxifloxacin-treated patients with infections caused by penicillin-resistant (one of one) or penicillin-intermediate (four of four) strains, whereas clinical cures were achieved in zero of one and one of three comparator regimen-treated patients with infections caused by penicillin-resistant and penicillin-intermediate strains, respectively. There were fewer instances of persisting pathogens (all of which were presumed cases of persisting infection) in respiratory samples from patients treated with moxifloxacin than in samples from patients in the comparator group, which included some patients with documented cases of persisting infections. The few cases of superinfection seen in this study all occurred in patients treated with the comparator regimen.

Table 4 presents the bacteriological responses by organism and source.

TABLE 4.

Bacteriological responses, by organism

| Organisma and specimen or test | Bacteriological response in microbiologically valid population (no. of patients who responded/ total no. of patients [%]) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOC (5-7 days after end of therapy) |

Follow-up (21-28 days after end of therapy) |

|||

| Moxifloxacin group | Comparator group | Moxifloxacin | Comparator | |

| S. pneumoniae | ||||

| Sputum | 18/18 (100) | 17/22b (77.3) | 14/18c (77.8) | 16/22d (72.7) |

| Blood | 11/11 (100) | 9/10 (90.0) | 11/11 (100) | 7/10e (70.0) |

| H. influenzae | ||||

| Sputum | 11/11 (100) | 8/9f (88.9) | 9/11g (81.8) | 6/9h (66.7) |

| Blood | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) |

| S. aureus | ||||

| Sputum | 2/2 (100) | 1/3i (33.3) | 2/2 (100) | 1/3g (33.3) |

| Blood | 0/1j | 1/1 (100) | 0/1k | 0/1k |

| H. parainfluenzae sputum | 0/1j | 3/3 (100) | 0/1k | 3/3 (100) |

| E. coli, sputum | 2/3j (66.7) | 2/3k (66.7) | ||

| P. aeruginosa, sputum | 1/2f (50) | 1/2k (50) | ||

| M. pneumoniae, serology | 13/13 (100) | 16/17j (94.1) | 12/13k (92.3) | 16/17j (94.1) |

| Chlamydia sp., serology | 3/3 (100) | 4/5j (80) | 3/3 (100) | 4/5j (80) |

| L. pneumophila, serology | 1/1 (100) | 3/4j (75) | 1/1 (100) | 3/4j (75) |

Only commonly identified or noteworthy pathogens are shown.

Presumed persistence n = 4; indeterminate, n = 1.

Eradication with recurrence, n = 1; indeterminate, n = 3.

Indeterminate, n = 6.

Indeterminate, n = 3.

Documented persistence, n = 1.

Indeterminate, n = 2.

Eradication with recurrence n = 1; indeterminate, n = 2.

Presumed persistence, n = 1; documented persistence, n = 1.

Presumed persistence, n = 1.

Indeterminate, n = 1.

For the subgroup of patients valid for microbiological analysis, the clinical cure rates on days 5 to 7 were 93.8 and 81.7% for the moxifloxacin (n = 60) and comparator (n = 58) groups, respectively. In order to be valid for microbiological analysis, patients had to have been eligible for the PP analysis, a causative organism(s) had to have been identified from a pretreatment sputum or blood specimen or paired serology samples, and the patient had to have had an appropriate bacteriological evaluation at the TOC visit on days 5 to 7. Overall, 17 of 17 moxifloxacin-treated patients and 22 of 24 comparator regimen-treated patients with atypical infections had a clinical cure at the TOC visit. The majority of comparator regimen-treated patients with atypical infections received clarithromycin: 10 of 17 patients infected with M. pneumoniae, 4 of 5 patients infected with Chlamydia spp., and 2 of 4 patients infected with L. pneumophila.

The rate of clinical cure was higher in the moxifloxacin group in both patients with nonsevere pneumonia and patients with severe pneumonia. Among the moxifloxacin-treated patients, the clinical cure rates were 94.6% for those with nonsevere pneumonia and 92.2% for those with severe pneumonia. Among the patients treated with the comparator regimen, the clinical cure rate for patients with nonsevere pneumonia was 86% and that for patients with severe pneumonia was 84.7%.

The differences in clinical cure and bacteriological success rates between the two treatment groups, together with the 95% CI for the populations that were included in both the PP and the ITT analyses, are depicted in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Clinical and bacteriological outcomes. ▪, point estimate of the difference between groups; horizontal bars, 95% CI.

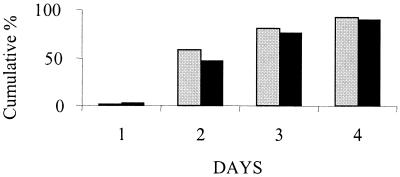

Before the start of treatment the mean ± standard deviation (SD) temperatures for the populations included in the ITT analysis were 38.7 ± 0.9°C for the moxifloxacin group and 38.8 ± 1.0°C for the comparator group. The time to resolution of temperature (defined as the first day at which the patient's peak temperature was less than or equal to 37.5°C) was analyzed by both the log rank test and the Wilcoxon test. The results are illustrated in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Cumulative percentage of patients in whom fever had resolved. ░⃞, moxifloxacin group; ▪, comparator group.

The median time to temperature resolution was 2 days for patients treated with moxifloxacin and 3 days for those treated with the comparator regimen. Among the population included in the ITT analysis, 140 (58.6%) of moxifloxacin-treated patients were apyrexic by day 2, whereas 119 (46.7%) of the patients in the comparator group were apyrexic by day 2 (P = 0.025 by the log rank test and P = 0.009 by the Wilcoxon test). The mean time to resolution of temperature was shorter in the moxifloxacin group than the comparator group, irrespective of disease severity. When the analysis was repeated by using a definition of apyrexia as a temperature of ≤38°C, the result was still statistically significant (P = 0.018 by the log rank test and P = 0.002 by the Wilcoxon test). The faster return to apyrexia in the moxifloxacin-treated patients could not be attributed to a greater use of drugs that may have contributed to a lowering of their temperatures (Table 5). Similarly, when only patients whose fevers resolved by day 2 and who used an antipyretic at some point during the study are considered, fewer moxifloxacin-treated patients (57.8%) than comparator regimen-treated patients (66.1%) were using antipyretic drugs at day 2.

TABLE 5.

Number of patients receiving medications that may have contributed to lowering of temperature (ITT analysis)

| Drug | No. of patients |

|

|---|---|---|

| Moxifloxacin group | Comparator group | |

| Acetaminophenb | 99 | 116 |

| Aspirinb | 16 | 25 |

| Corticosteroids | 28 | 39 |

| NSAIDc | 1 | 0 |

| Totalb | 144 | 173 |

Patients may have received more than one agent.

Alone or in combination preparations.

NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (diclofenac).

Among the population in the ITT analysis, the mean ± SD duration of i.v. treatment for moxifloxacin-treated patients was 4.02 ± 1.78 days, whereas it was 4.81± 2.07 days for the comparator regimen-treated patients, suggesting that moxifloxacin-treated patients were able to switch to oral therapy at an earlier stage than those who were receiving the comparator regimen. Among the patients in the ITT analysis, approximately half (n = 151 [50.2%]) of the patients in the moxifloxacin group received therapy for only 3 days or less, whereas less than a fifth (n = 57 [17.8%]) of the patients treated with the comparator drug received therapy for only 3 days or less.

The mean ± SD duration of the hospital stay was 9.49 ± 7.29 days for the moxifloxacin group (n = 301) and 10.41 ±7.49 days for the comparator group (n = 321). The duration of the hospital stay was not the subject of formal statistical testing, as in the study protocol this parameter was planned for descriptive analysis only.

Tolerability and safety.

Data for 301 moxifloxacin-treated patients and 321 comparator regimen-treated patients were valid for the safety analysis. Within the latter group, 192 patients (60%) were treated with both co-amoxiclav and clarithromycin and 129 patients received co-amoxiclav alone.

Fifteen patients (5.0%) in the moxifloxacin group and 13 patients (4.0%) in the comparator group were prematurely discontinued from the study due to adverse events. The causes for discontinuation possibly or probably related to treatment that occurred in more than one patient included abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) or hepatic disturbance (one in the moxifloxacin group, five in the comparator group); rash (two in the moxifloxacin group, one in the comparator group); allergic reaction (two in the moxifloxacin group); diarrhea (two in the moxifloxacin group); and pancreatitis and elevation of pancreatic enzyme levels (one in the moxifloxacin group, two in the comparator group). No other single event caused a high number of discontinuations in either group. Single events possibly or probably related to a study drug that led to discontinuation included dizziness, nausea, acute gastroenteritis, fever, and confusion for the moxifloxacin group and pruritus and gastralgia for the comparator group. All drug-related adverse events that led to discontinuation improved or resolved without serious sequelae.

During the course of the study there were 26 deaths: 9 in the moxifloxacin group (2 of these occurred after the 30-day follow-up) and 17 in the comparator group. This was not a statistically significant difference. Most deaths were due to pneumonia or underlying lung disease (6 in the moxifloxacin group and 10 in the comparator group). The average age at death was 76 years in the moxifloxacin group and 71 years in the comparator group. Apart from death, other serious adverse events were defined as a life-threatening drug experience, hospitalization or prolongation of existing hospitalization, a persistent or significant disability or incapacity, and important medical events that required medical or surgical intervention. Serious adverse events were reported in 38 patients (12.6%) treated with moxifloxacin and 53 patients (16.5%) treated with the comparator regimen. There were more serious adverse events within the respiratory system for both treatment groups (18 [6.0%] in the moxifloxacin group, 25 [7.8%] in the comparator group). Twelve patients (4.0%) in the moxifloxacin group and 20 patients (6.2%) in the comparator group were reported to have serious cardiovascular adverse events.

When all body systems were taken into account, the most common (incidence, ≥3.0%) drug-related adverse events were abnormal LFTs, diarrhea, and nausea for the moxifloxacin group and abnormal LFTs, diarrhea, nausea, and phlebitis for the comparator group. There were no cases of phototoxicity. The incidence of drug-related adverse events was highest for those events related to the gastrointestinal tract and was similar in both groups (20.9% for the moxifloxacin group and 22.1% for the comparator group). The most frequent gastrointestinal events were abnormal LFTs, diarrhea, and nausea. The types and severities of events were similar between the two treatment groups. The distributions of mild, moderate, and severe abnormal LFTs were comparable between the two treatment groups (15 mild, 6 moderate, and 1 severe LFTs for the moxifloxacin group; 9 mild, 9 moderate, and 1 severe LFTs for the comparator group). There were fewer drug-related cardiovascular events in the moxifloxacin group (20 [6.6%]) than in the comparator group (32 [10%]). There was only one report of a treatment-emergent clinically significant QTc prolongation, and this was in a patient treated with co-amoxiclav. There were no cases of torsade de pointes.

The vast majority of drug-related adverse events in both treatment groups were mild or moderate, irrespective of whether the study medication was administered by the i.v. or oral route, and their incidences were as follows: for moxifloxacin administered i.v., 70 of 79 (89%) patients; for moxifloxacin administered orally, 43 of 50 (86%) patients; for the comparator regimen administered i.v., 77 of 88 (88%) patients; for the comparator regimen administered orally, 38 of 38 (100%) patients. The incidence of drug-related adverse events was 38.9% in both treatment groups, and their outcomes were similar. Thus, the proportions of drug-related adverse events described as resolved or improved were 84% (98 of 117) for the moxifloxacin group and 85% (106 of 125) for the comparator group.

Most adverse events in both treatment groups were experienced during the period of i.v. administration. During i.v. therapy, the incidence rates for all drug-related adverse events were 26.2% for the moxifloxacin group and 27.4% for the comparator group. The incidences of drug-related adverse events during oral therapy were 16.6% for the moxifloxacin group and 11.8% for the comparator group.

High and low laboratory values were defined as those which occurred in ≥2.5% of the study population in at least one of the two treatment groups. In addition, there were predefined criteria for clinically significant changes of selected laboratory values (decrease of the hematocrit level of at least 20%, decrease of the hemoglobin concentration of at least 2 g/liter, decrease of the platelet count of at least 25%, increase of the serum creatinine level of at least 0.6 mg/dl, increase of the blood urea nitrogen level of at least 75%, increase of the aspartate aminotransferase level of at least 100% and at least 10 U/liter, increase of the alanine aminotransferase level of at least 100% and at least 10 U/liter, increase of the alkaline phosphatase level of at least 50% and at least 50 U/liter, and increase of the total bilirubin level of at least 200%). For the moxifloxacin and the comparator groups, the incidences of high abnormal values were 17.5 and 20.3%, respectively; the incidences of low abnormal values were 16.9 and 17.6%, respectively; and the incidences of selected clinically significant values were 9.8 and 10.9%, respectively. The types of abnormalities observed were not different between the two treatment groups, and no unexpected abnormalities were observed.

DISCUSSION

Because the rate of mortality is significantly increased in patients with severe CAP and because it may be caused by a number of different pathogens unknown at the time of presentation, there are compelling reasons for empirical treatment. It is often difficult to identify a specific etiology for CAP since there is no distinctive pattern of signs and symptoms for an individual group of pathogens or an individual species of pathogen and since appropriate diagnostic tests fail to identify a pathogen in approximately 50% of cases. Because of these diagnostic difficulties, combination therapy is often used to cover all common pathogens that cause CAP. Moxifloxacin is a new fluoroquinolone with activity against the common gram-positive, gram-negative, and atypical pathogens that cause CAP. Thus, it is an ideal monotherapeutic regimen for the empirical treatment of CAP. The purpose of this study was to compare sequential i.v. and oral moxifloxacin therapy to a standard regimen of co-amoxiclav with or without clarithromycin.

Due to its complexity, an open-label study design was used. Although an open-label design introduces the possibility of bias, this was minimized by using a standardized methodology to determine the clinical response to treatment. The objectivity of these clinical judgments was supported by consistency between the clinical and bacteriological outcomes, including the outcomes for objective criteria such as the resolution of fever.

The microbial epidemiology of the study reflects those described in previous reports. Causative organisms were identified in 59.5% of patients for whom cultures or serology was performed. It is known that no specific cause is found in as many as 30 to 60% of patients even when extensive diagnostic testing is performed (15). In patients with documented infections, the most frequently isolated organism was S. pneumoniae (55.4% of identified pathogens), followed by H. influenzae (19.6%). Atypical organisms accounted for 13.8% of infections, a result that is consistent with those from a series of three well-defined studies (12, 13, 14) in which the incidence ranged from 2.7 to 10% in patients requiring admission to a hospital.

The rate of clinical cure was significantly higher in patients treated with moxifloxacin than in patients treated with the comparator regimen. Our results are consistent with those of a previous study (8) of levofloxacin compared with ceftriaxone and/or cefuroxime axetil with or without erythromycin or doxycycline. However, in the levofloxacin study, most patients (84%) had nonsevere CAP and the difference between treatment groups was less marked (clinical success rate for the levofloxacin group, 96%; clinical success rate for the group receiving the comparator regimen, 90%). Unlike the present study, the observed difference was not subject to a formal test of superiority. It is of note that a retrospective examination (10) of the hospital records for 12,945 patients, aged 65 years and older, hospitalized for pneumonia showed that initial treatment with an expanded-spectrum cephalosporin or a nonpseudomonal broad-spectrum cephalosporin together with a macrolide or fluoroquinolone monotherapy was independently associated with lower 30-day mortality rates. The use of a β-lactam-β-lactamase inhibitor with a macrolide or an aminoglycoside with a macrolide was associated with an increased 30-day mortality rate.

In an equivalence or noninferiority trial, similar conclusions from both the ITT and PP analyses are required for a robust interpretation (7). Since the results presented here for the ITT analyses were the same as those for the primary outcome measure and other secondary clinical outcomes in the PP analyses, it is reasonable to conclude that the differences between treatment groups are likely to be medically significant. This interpretation is also supported by consistent differences in favor of moxifloxacin for those outcomes for which, due to a lack of statistical power, formal analysis was inappropriate.

The time to resolution of fever was significantly shorter for moxifloxacin-treated patients. Although the proportions of patients with a fever, as measured by various routes (oral, tympanic, axillary, or rectal), were similar in both treatment groups, in order to take account of any differences, a conservative definition of apyrexia, namely, a body temperature of ≤37.5°C, was used in the main analysis. However, it must be emphasized that even when the definition of resolution of fever was considered a body temperature of ≤38°C, the result was still statistically significant. Furthermore, the rate of use of antipyretics was less among patients treated with moxifloxacin than among those given the comparator regimen and suggests a direct treatment effect.

The observation of a shorter time to resolution of fever is consistent with a more rapid onset of treatment effect and is supported by the observation that approximately half (50.2%) of the moxifloxacin-treated patients received i.v. therapy for only 3 days or less, whereas less than a fifth (17.8%) of the patients treated with the comparator regimen received i.v. therapy for only 3 days or less. After 3 days, the time at which patients were converted to oral therapy was entirely at the discretion of the investigator. The mean duration of hospital admission for the moxifloxacin-treated patients was approximately 1 day less than that for those treated with the comparator regimen.

Clinical trials of earlier conversion from i.v. to oral therapy (17, 18) have demonstrated that the duration of hospital admission can be reduced without compromising patient outcomes. The Pneumonia Patient Outcomes Research Team cohort study (9) concluded that, despite differences between hospitals in the total costs of care, the patterns of daily resource use were similar and that a 1-day reduction in the length of stay might yield substantial cost savings. A preliminary analysis of data from that study found health economic benefits of moxifloxacin therapy over comparator therapy (M. Drummond, R. Finch, I. Duprat-Lomon, P. P. Sagnier, O. Collins, R. Kubin, and M. Hux, Abstr. 41st Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 864, 2001). The clinical response at late follow-up, that is, 21 to 28 days after the end of treatment, demonstrates that the shorter period of hospitalization does not affect the longer-term outcomes for moxifloxacin-treated patients.

The potential cost advantage of monotherapy with a fluoroquinolone over combination treatment with a β-lactam and a macrolide has recently been confirmed by an independent cost analysis (5). That work examined the results of a prospective randomized clinical trial of sequential i.v. or oral gatifloxacin therapy compared with ceftriaxone and erythromycin or clarithromycin therapy in patients with CAP. The analysis took account of the costs of drug acquisition, dispensing, administration, treatment failure, adverse events, and hospitalization. Despite the similar periods of i.v. drug administration and the lack of statistically significant differences in clinical and microbiological outcomes, gatifloxacin was shown to be more cost-effective.

When one is selecting an antimicrobial agent for the treatment of CAP, it is important to consider not only efficacy but also how well it is likely to be tolerated by patients. In the trial described here, sequential i.v. and oral treatment with both regimens, moxifloxacin or co-amoxiclav with or without clarithromycin, was well tolerated. Most adverse events in both treatment groups were considered to be of mild to moderate intensity, regardless of the mode of administration.

There were fewer serious adverse events and deaths in the moxifloxacin group than in the comparator group. The smaller number of deaths in patients treated with moxifloxacin is consistent with a previous meta-analysis of three comparative studies of the treatment of CAP with oral moxifloxacin [M. Niederman, D. Church, J. Kaufmann, and M. Springsklee, abstract from Forum on Respiratory Infections 2000, Respir. Med. 94(Suppl. A):A14, 2000]. The analysis was of all causes of mortality within 30 days posttreatment and showed that in the cohort of 701 patients treated with moxifloxacin there were 4 deaths (0.57%), whereas there were 12 deaths (1.70%) in the 705 patients treated with the comparator regimen (P = 0.045). The incidences of laboratory abnormalities and premature discontinuations were similar in both groups.

The higher incidence of cardiovascular events seen in patients treated with the comparator regimen was largely due to a higher rate of phlebitis. There were no clinically significant (6) cases of treatment-emergent QTc prolongation in the moxifloxacin group, and there was only one case in the comparator group. There were no cases of torsade de pointes. Although it has been reported that several quinolones cause phototoxic reactions, no patients complained of phototoxicity. This is consistent with the safety experience reported with oral moxifloxacin (R. Kubin and C. Reiter, Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 820, 2000).

The present study was in accord with existing European (2, 4, 19) and North American (1) guidelines for the evaluation of antibacterial agents, which allow the use of study designs in which assessment times are determined by clinical judgment. Such study designs fail to take account of the rate of response and favor the demonstration of equivalence rather than differences between treatments. This is further compounded by definitions of equivalence or statistical hypotheses that allow greater differences between treatment effects. In this study the assessment periods were determined by the point at which the patient's condition had improved to the extent that the patient was well enough for treatment to be discontinued. Hence, it might be anticipated that the clinical statuses of patients at these times might not be dissimilar. Notwithstanding these considerations, the results of this study, designed to demonstrate equivalence, show that moxifloxacin was statistically significantly more effective, in terms of clinical and bacteriological outcomes, than a standard combination regimen included in a number of treatment guidelines for CAP. This superiority was seen in patients irrespective of the severity of their pneumonia and whether or not the combination therapy included a macrolide. The high rate of bacteriological success of moxifloxacin, observed at the TOC visit, against those organisms known to be important causes of CAP, including drug-resistant S. pneumoniae, was maintained at late follow-up. The results for the primary outcome, clinical response, were supported by the faster resolution of fever and the earlier conversion from i.v. to oral administration in patients treated with moxifloxacin. Moxifloxacin treatment was associated with fewer deaths, fewer serious adverse events, and fewer other adverse events. Given that data from prospective, randomized trials are the major source of information for evidence-based medicine, it is concluded that the results presented here may have implications for clinical guidelines.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of the following investigators: in Belgium, R. Peleman, D. Galdermans, and E. Janssens; in France, O. Ruyer, G. Dien, I. Caby, C. D. Guyonnaud, L. Vives, X. Forecville, L. Cellerin, D. Debieuvre, P. Delaval, M. David, J. Boyer, and B. Fantin; in Germany, S. Kljucar, H. Koch, P. M. Shah, A. Schwarz, L. Greiner, L. Bölcskei, J. Schauer, H. Lode, W. Kreisel, and O. Cornely; in Greece, H. Bassaris and E. Papadakis; in Spain, F. Álvarez Lerma and G. Juan Samper; in the United Kingdom, P. Rafferty, R. C. Read, P. B. Anderson, D. R. T. Shepherd, G. S. Basran, M. Farrington, R. J. O. Davies, K. G. Nicholson, R. N. Davidson, and C. G. Wathen; in Israel, E. Rubinstein, R. K. Cohen, and D. Seltzer; in Switzerland, J.-D. Baumgartner, J. Garbino, and D. Genné; and in South Africa, L. Fourie, J. G. Kilian, C. Feldman, T. J. Gray, J. H. J. van Rensburg, A. Jacovides, M. J. Heystek, N. Du Toit.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beam, T. R., D. N. Gilbert, and C. M. Kunin. 1992. General guidelines for the clinical evaluation of anti-infective drug products. Clin. Infect. Dis. 15(Suppl.):S5-S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beam, T. R., D. N. Gilbert, and C. M. Kunin. 1993. General guidelines for the clinical evaluation of anti-infective drug products. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Munich, Germany.

- 3.The British Thoracic Society. 1993. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults admitted to hospital. Br. J. Hosp. Med. 49:346-350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. 1997. Notes for guidance on evaluation of new anti-bacterial medical products. 3983:CPMP/EWP/558./95. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical Products, London, United Kingdom.

- 5.Dresser, L. D., M. S. Niederman, and J. A. Paladino. 2001. Cost-effectiveness of gatifloxacin vs ceftriaxone with a macrolide for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. Chest 119:1439-1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical Products. 1997. Points to consider: the assessment of the potential for QT interval prolongation by non-cardiovascular medicinal products. CPMP/986/96. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medical Products, London, United Kingdom.

- 7.The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. 1999. Points to consider on biostatistical/methodological issues arising from recent CPMP discussions on licensing applications: superiority, non-inferiority and equivalence. CPMP/EWP/482./99. The European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products, London, United Kingdom.

- 8.File, T. M., Jr., J. Segreti, L. Dunbar, R. Player, R. Kohler, R. R. Williams, C. Kojak, and A. Rubin. 1997. A multicenter, randomized study comparing the efficacy and safety of intravenous and/or oral levofloxacin versus ceftriaxone and/or cefuroxime axetil in treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1965-1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fine, M. J., H. Pratt, D. S. Obrosky, J. R. Lave, L. J. McIntosh, D. E. Singer, C. M. Coley, and W. N. Kapoor. 2000. Relation between length of hospital stay and cost of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am. J. Med. 109:378-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gleason, P. P., T. P. Meehan, J. M. Fine, D. H. Galusha, and M. J. Fine. 1999. Associations between initial antimicrobial therapy and medical outcomes for hospitalized elderly patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 159:2562-2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guest, J. F., and A. Morris. 1998. Community acquired pneumonia: the annual cost to the National Health Service in the UK. Eur. Respir. J. 10:1530-1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandell, L. A. 1999. Advances in antimicrobial therapy of community acquired pneumonia. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 112:137-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marrie, T. J. 1994. Community acquired pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:501-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marston, B. J., J. F. Plouffe, T. M. File, Jr., B. A. Hackman, S. J. Salstron, H. B. Lipman, M. S. Kolczak, and R. F. Breiman. 1997. Incidence of community acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalisation: results of a population-based active surveillance study in Ohio. Arch. Intern. Med. 157:1709-1718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neu, H. C. 1992. The crisis in antibiotic resistance. Science 257:1064-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niederman, M. S., J. B. Bass, G. D. Campbell, A. M. Fein, R. F. Grossman, L. A. Mandell, T. J. Marrie, G. A. Sarosi, A. Torres, and V. L. Yu. 1993. Guidelines for the initial management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia: diagnosis, assessment of severity, and initial antimicrobial therapy. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 148:1418-1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramirez, J. A., L. Srinath, S. Aklee, A. Huang, M. J. Raff. 1995. Early switch from intravenous to oral cephalosporin in the treatment of hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch. Intern. Med. 155:1273-1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siegel, R. E., N. A. Halpern, P. L. Almenoff, A. Lee, R. Cashin, and J. G. Greene. 1996. A prospective randomized study of inpatient IV antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia: the optimum duration of therapy. Chest 1 10:965-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Working Party of The British Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 1989. The clinical evaluation of antibacterial drugs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 23(Suppl. B):1-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]