Abstract

The sequenced chromosome of Caulobacter crescentus CB15 encodes a hypothetical protein that exhibits significant similarity (30 to 35% identical residues) to metallo-β-lactamases of subclass B3. An allelic variant of this gene (divergent by 3% of its nucleotides) was cloned in Escherichia coli from C. crescentus type strain DSM4727. Expression studies confirmed the metallo-β-lactamase activity of its product, CAU-1. The enzyme produced in E. coli was purified by two ion-exchange chromatography steps. CAU-1 contains a 29-kDa polypeptide with an alkaline isoelectric pH (>9), and unlike the L1 enzyme of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, the native form is monomeric. Kinetic analysis revealed a preferential activity toward penicillins, carbapenems, and narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, while oxyimino cephalosporins were poorly or not hydrolyzed. Affinities for the various β-lactams were poor overall (Km values were always >100 μM and often >400 μM). The interaction with divalent ion chelators appeared to occur by a mechanism similar to that prevailing in other members of subclass B3. In C. crescentus, the CAU-1 enzyme is produced independently of β-lactam exposure and, interestingly, the blaCAU determinant is bracketed by three other genes, including two genes encoding enzymes involved in methionine biosynthesis and a gene encoding a putative transcriptional regulator, in an operon-like structure. The CAU-1 enzyme is the first example of a metallo-β-lactamase in a member of the α subdivision of the class Proteobacteria.

Metallo-β-lactamases are bacterial enzymes that hydrolyze β-lactam compounds with the help of a metal cofactor (8, 38). They are structurally and mechanistically unrelated to the more prevalent serine β-lactamases and are included in molecular class B of Ambler's structural classification (2) and in group 3 of the functional classification (9, 28). The clinical relevance of these enzymes essentially depends on their ability to hydrolyze carbapenem compounds, which are stable in the presence of most serine β-lactamases and are usually regarded as last-resort antibiotics for multidrug-resistant strains (7, 24). In fact, most metallo-β-lactamases exhibit a broad substrate specificity and can be responsible for broad-spectrum β-lactam resistance (7, 8, 24, 28). From the fundamental standpoint, metallo-β-lactamases have become important investigational models for the protein chemistry and enzymology of zinc enzymes. However, the structure-function relationships and the catalytic mechanism(s) of these enzymes are only partially understood and their evolutionary history remains unclear (8, 38).

Far from being ubiquitous, most metallo-β-lactamase determinants are found as resident genes in some species that are primarily members of the environmental microbiota (such as Bacillus cereus, some Aeromonas species, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, Chryseobacterium meningosepticum, Chryseobacterium indologenes, Legionella gormanii, and Janthinobacterium lividum) (3, 4, 6, 19, 30-32, 37). Only recently have metallo-β-lactamase determinants carried by mobile genetic elements started spreading among major clinical pathogens (7, 24). Further knowledge of their distribution could help to identify the original sources of mobile metallo-β-lactamase determinants and increase our understanding of their intriguing evolutionary history.

The rapid progress of large-scale sequencing projects is now providing a large amount of data for several microbial genomes, leading to the discovery of new putative members of known protein families. A number of hypothetical proteins encoded by various genomes have been identified that are related to known members of the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily (included in cluster of orthologous groups no. 0491; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), but their orthologous nature has not been experimentally demonstrated.

In this work, we cloned a putative metallo-β-lactamase determinant that was postgenomically identified in the chromosome of Caulobacter crescentus, demonstrated its orthologous nature, and characterized its product, CAU-1. C. crescentus is a gram-negative inhabitant of dilute aquatic environments that differentiates and divides asymmetrically at each cell cycle and represents the most popular procaryotic model system used to study cellular differentiation, asymmetric division, and their coordination with the cell cycle (27).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

C. crescentus DSM4727T was investigated for metallo-β-lactamase production and used as the source of genomic DNA for cloning of the blaCAU-1 gene and to study its genetic environment. Escherichia coli DH5α (Gibco Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used as the host for recombinant plasmids and for expression experiments. C. crescentus was grown aerobically at 25°C in Caulobacter medium as recommended by the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany). E. coli clones were grown aerobically at 28°C in LB medium (33) unless otherwise specified.

β-Lactam compounds and other chemicals.

β-Lactam compounds and other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) unless otherwise specified. Imipenem, meropenem, cefuroxime, ceftazidime, aztreonam, cefepime, moxalactam, and nitrocefin were obtained from commercial sources as described previously (22).

In vitro susceptibility testing.

The in vitro susceptibility of E. coli DH5α carrying different plasmids and of C. crescentus DSM4727T was determined by a macrodilution broth method with Mueller-Hinton broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) for E. coli and caulobacter medium for C. crescentus and a bacterial inoculum of 105 CFU per tube. Results were recorded after incubation at 28°C for 24 h. Otherwise, the procedure was as recommended by the NCCLS (26).

Recombinant DNA methodology and DNA analysis techniques.

Basic recombinant DNA procedures were performed as described by Sambrook et al. (33). Extraction of genomic DNA from C. crescentus was performed as described previously (20). Plasmid extraction was done by the alkaline lysis method (33). PCR was done with the Expand PCR system (Roche Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, in a 50-μl volume with 50 pmol of each primer and 100 ng of bacterial genomic DNA as the template. The primers used for cloning experiments and PCR mapping were CAU-OP/F (5′-GGCGCTCTAGAGCAGGTGCTGTCGATCGTTTG), BLA-CAU/F (5′-TCGCGATTAAGGAGGTCGCCGCATGAAGCG), CAU-MET/R (5′-GAGAATGAGAATACGCTCCTTGG), and CAU-OP/R (5′-GATGTTGACGAAGACGGGGCGC). Their locations are shown in Fig. 1. The cycling conditions included a denaturation step of 96°C for 45 s, an annealing step at a primer-dependent temperature for 90 s, and an extension step of 72°C for a primer-dependent time, repeated for 30 cycles. Annealing temperatures and extension times were 60°C and 3 min, respectively, with primers BLA-CAU/F and OP-CAU/R; 56°C and 5 min, respectively, with primers OP-CAU/F and MET-CAU/R; and 56°C and up to 8 min, respectively, with primers OP-CAU/F and OP-CAU/R. Analysis of genomic DNA of C. crescentus by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was done as described previously (11). The I-CeuI enzyme was from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.). Southern blot assays were performed with dried gels and 32P-labeled probes as described previously (35). The blaCAU-1 probe was made of the 1-kb PCR amplicon obtained with primers BLA-CAU/F and CAU-MET/R. The 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) probe was made of a 434-bp PCR amplicon corresponding to nucleotides 1088 to 1522 (according to the standard numbering of 16S rDNA [1]) of the C. crescentus 16S rDNA. DNA sequences of both strands were determined directly on PCR amplicons or on plasmid templates as described previously (29). Similarity searches against sequence databases were performed with an updated version of the BLAST program at the BLAST interface of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). A multiple-sequence alignment was generated on the basis of the alignment used in the BBL numbering scheme for class B enzymes (15), and the same scheme was used for numbering throughout this report. Construction of plasmid pFG2003 was done as follows. The 2.2-kb chromosomal region containing the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene (CC2139) and the downstream CC2138 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with primers BLA-CAU/F and OP-CAU/R (Fig. 1) and blunt end cloned into the SmaI site of plasmid pUC-18 to obtain recombinant plasmid pFG2001, in which the ORFs were in an orientation opposite to that of the lacZ α-peptide-encoding gene. The 2.2-kb EcoRI-XbaI insert of pFG2001, containing the cloned amplicon, was then subcloned into plasmid pBC-SK (Stratagene Inc., La Jolla, Calif.) to obtain recombinant plasmid pFG2002, in which the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene was located downstream of the Plac promoter flanking the vector polylinker. This plasmid was then digested with StuI and EcoRV and self-ligated to obtain pFG2003, in which the CC2138 ORF is partially deleted (Fig. 1).

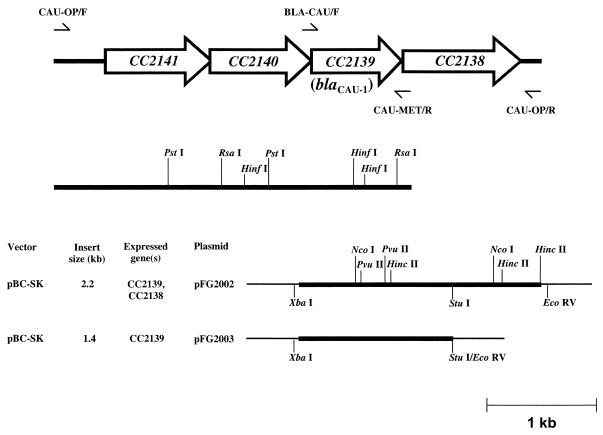

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of the C. crescentus CB15 chromosomal region containing ORF CC2139, corresponding to the blaCAU gene. ORFs are indicated by arrows. The position and orientation of the primers used for PCR cloning and mapping procedures as described in Materials and Methods are indicated above and below the map. The amplicons obtained from the genome of C. crescentus DSM4727T with primers CAU-OP/F and CAU-MET/R or primers BLA-CAU/F and CAU-OP/R are indicated by thick lines below the map, and the restriction sites used to confirm their identities are also shown. The 2.2-kb amplicon obtained with primers CAU-OP/F and CAU-MET/R corresponds to the insert of plasmid pFG2002 (thin lines represent vector sequences). Plasmid pFG2003, used for expression experiments, was generated from pFG2002 following partial removal of the CC2138 ORF as described in Materials and Methods.

Purification of the CAU-1 enzyme.

The CAU-1 enzyme was purified from E. coli DH5α(pFG2003) as follows. The strain was grown aerobically at 37°C for 16 h in 100 ml of buffered super broth (yeast extract at 20 g/liter-Tryptone at 35 g/liter-NaCl at 5 g/liter buffered with 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer [PB], pH 7.0) containing chloramphenicol (85 μg/ml). (Isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside [IPTG] was not added to the culture since, in preliminary experiments, addition of the inducer did not improve the yield of recombinant enzyme.) Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 5 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM MgCl2, and disrupted by sonication (five times, for 30 s each time, at 45 W). Cell debris were removed by high-speed centrifugation (45,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C), and the clarified supernatant was loaded (flow rate, 1 ml/min) onto a DEAE-Sepharose FF column (1 by 20 cm; bed volume, 15 ml; Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Milan, Italy) equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). Under these conditions, the enzyme eluted in the flowthrough while most of the other proteins were retained by the column. The enzyme-containing fractions were pooled, and the buffer was changed to 20 mM 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES)-KOH (pH 6.0) with a PD10 column (Amersham-Pharmacia). The protein solution was then loaded (flow rate, 2 ml/min) onto a Source 15S HR column (1.6 by 5 cm; bed volume, 10 ml; Amersham-Pharmacia) equilibrated with the same buffer, and the enzyme was eluted with a linear NaCl gradient (0 to 1 M in 100 ml) in the same buffer. The enzyme-containing fractions were pooled and stored at −20°C until used.

Size exclusion chromatography.

Size exclusion chromatography was done on a Superdex 75 HR 10/30 column (Amersham-Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM PB (pH 7.5) containing 0.25 M NaCl. The purified enzyme (100 μl at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml) was eluted in the same buffer at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The low-range gel filtration calibration kit (Amersham-Pharmacia) was used for column calibration. Apparent partition coefficients (Kav) were calculated as described previously (18).

Protein electrophoretic techniques.

Analytical isoelectric focusing and subsequent zymographic detection of β-lactamase bands were done as described previously (23). Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was done as described by Laemmli (21), with final acrylamide concentrations of 15 and 5% (wt/vol) for the separating and stacking gels, respectively. After electrophoresis, the protein bands were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250.

N terminus sequencing and electrospray mass spectrometry.

The amino-terminal sequence of the purified CAU-1 protein was determined with a 477A protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) as described previously (25). Electrospray mass spectrometry was done with a PE-Sciex API III triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, Rahway, N.J.) equipped with an ion spray source. The sample (150 pmol) was resuspended in 1% (vol/vol) potassium formate-70% (vol/vol) acetonitrile in water and injected into the source of the mass spectrometer at a flow rate of 20 μl/min. The source and cone voltages were 5.5 kV and 60 V, respectively. The source temperature was kept at 50°C. Twenty-four scans covering 800 to 1,800 atomic mass units were accumulated, and data were analyzed with the software delivered with the instrument.

β-Lactamase assays and determination of kinetic parameters.

Metallo-β-lactamase activity in crude extracts and during the purification procedure was assayed spectrophotometrically by monitoring the hydrolysis of meropenem (150 μM) at 300 nm (Δɛ, −6,500 M−1 cm−1). Reactions were done with 50 mM PB (pH 7.0) at 30°C in a total volume of 500 μl. Inhibition of enzymatic activity by EDTA was assayed by measuring the residual carbapenemase activity after incubation of the crude extract for 20 min at 25°C in the presence of 5 mM EDTA. Crude cell extracts were prepared from liquid cultures as follows. Cells were collected by centrifugation, resuspended in PB (1/10 of the original culture volume), and disrupted by sonication (six times, for 15 s each time, at 50 W). The supernatant obtained after centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove cell debris provided the crude extract. The protein concentration in solution was assayed with a commercial kit (Bio-Rad Protein Assay; Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard. Substrate hydrolysis by the purified enzyme was monitored by measuring the absorbance variation at 30°C with a Cary 100 UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Varian Instruments, Walnut Creek, Calif.) in a total reaction volume of 500 μl in PB. The sources, wavelengths, and changes in extinction coefficients used in the spectrophotometric assays were the same as those described previously (22). The final enzyme concentrations ranged from 4 to 80 nM. The steady-state kinetic parameters (Km and kcat) were determined under initial-rate conditions with the Hanes-Woolf plot (34) and, in several cases, verified by analysis of the complete hydrolysis time courses as described by De Meester et al. (10). For cefepime and aztreonam, inhibition constants (Kis) were determined in a competitive model as described previously (14) with ampicillin (concentration range, 0.25 to 2 mM) as the reporter substrate. With cefepime, a Dixon plot (34) was used to determine the inhibition type.

Inactivation by chelating agents.

Inactivation time courses were monitored by measuring the hydrolysis of 150 μM meropenem, which was used as the reporter substrate, in the presence of different concentrations of EDTA and o-phenanthroline. The reaction conditions were the same as those used for determination of kinetic parameters (see above). The final enzyme concentration was 4 nM. Pseudo-first-order inactivation rate constants (kis) were determined at different inactivator concentrations.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been submitted to the EMBL/GenBank/DDBJ sequence databases and assigned accession number AJ308331.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cloning and characterization of a metallo-β-lactamase determinant from C. crescentus DSM4727T.

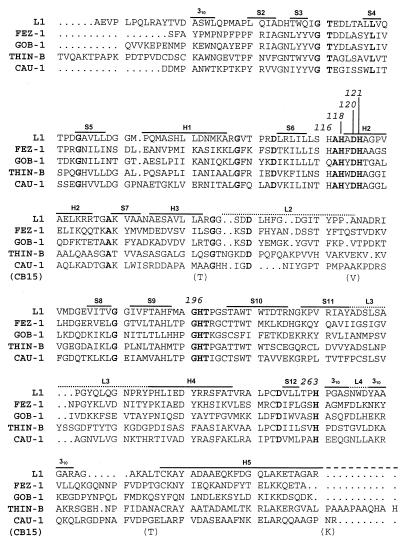

Postgenomic analysis revealed that the chromosome of C. crescentus CB15 contains an ORF (CC2139) encoding a hypothetical protein that belongs in the metallo-β-lactamase superfamily (27). Sequence comparisons showed that the similarity is greater (30 to 35% identical residues) with metallo-β-lactamases of subclass B3, including the L1 enzymes of S. maltophilia (37), the FEZ-1 enzyme of Legionella gormanii (6), the GOB enzymes of Chryseobacterium meningosepticum (3), and the THIN-B enzyme of Janthinobacterium lividum (30).

A 2.2-kb region containing the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene (CC2139) and a downstream ORF (CC2138) was amplified from the genomic DNA of C. crescentus DSM4727T by high-fidelity PCR with primers based on flanking regions according to the published sequence (Fig. 1). The amplicon was cloned in pUC18, subcloned in pBC-SK, and partially deleted to obtain recombinant plasmid pFG2003, in which the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene was located downstream of the Plac promoter flanking the vector polylinker, and the downstream CC2138 ORF was partially deleted (Fig. 1; see Materials and Methods for details of the cloning procedure). Sequencing of the pFG2003 insert revealed only minor differences from the chromosome of CB15 (3% within the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene, resulting in a difference of four amino acid residues, none of which were located in common motif areas; Fig. 2). The authenticity of these differences was confirmed by direct sequencing of the 2.2-kb PCR amplicon obtained from two independent amplification reactions. No plasmid DNA was detectable in C. crescentus DSM4727T, and a Southern blot analysis of undigested genomic DNA with a probe containing the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene yielded a hybridization signal only with the band of chromosomal DNA. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis of genomic DNA of DSM4727T, after digestion with I-CeuI (which only cuts in the 23S rDNA genes), yielded two bands of ca. 3,000 and 1,000 kb, respectively. In a Southern blot analysis, both bands hybridized to a 16S rDNA probe while only the largest band hybridized to the putative metallo-β-lactamase probe (data not shown). This pattern confirmed the chromosomal location of the putative metallo-β-lactamase gene and was consistent with that expected for C. crescentus CB15 (27).

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of subclass B3 metallo-β-lactamases. Positions of zinc ligand residues are numbered in accordance with the BBL scheme (15). Secondary structure elements (S, strands; 310 and H, helices; L, loops) of the L1 enzyme (36) are indicated above the sequences. References for the sequences are as follows: L1, reference 37; FEZ-1, reference 6; GOB-1, reference 3; THIN-B, reference 30. The four amino acid residues in the protein encoded by ORF CC2139 of C. crescentus CB15 that differ from CAU-1 are indicated below the sequence.

Analysis of a crude extract of E. coli DH5α(pFG2003) revealed the presence of carbapenemase activity (specific activity, 325 ± 38 μmol of imipenem hydrolyzed/min/g of protein) that was inhibited more than 95% by EDTA. A similar activity was also detected in a crude extract of C. crescentus DSM4727T grown in a medium with no added β-lactams (specific activity, 21 ± 3 μmol of imipenem hydrolyzed/min/g of protein; inhibited more than 95% by EDTA). Preliminary experiments done with ampicillin and meropenem as inducers at subinhibitory concentrations did not result in increased carbapenemase production by C. crescentus (data not shown). Analytical isoelectric focusing, developed with the chromogenic substrate nitrocefin, revealed the presence of a β-lactamase band with a pI of >9 in the crude extracts of both DH5α(pFG2003) and DSM4727T but not in the crude extract of the E. coli host carrying the empty vector (data not shown). E. coli DH5α(pFG2003) exhibited decreased in vitro susceptibility to several β-lactams, in comparison with DH5α(pBC-SK). The relative decrease in susceptibility was greater with penicillins and carbapenems than with cephalosporins. Susceptibility to aztreonam was not affected (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

β-Lactam susceptibility of C. crescentus DSM 4727T, and of E. coli DH5α(pFG2003), carrying the cloned blaCAU-1 gene and producing the CAU-1 enzymea

| Antibiotic | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| DSM 4727T | DH5α(pFG2003)b | DH5α(pBC-SK) | |

| Ampicillin | 64 | >64 | 1 |

| Carbenicillin | >64 | >64 | 4 |

| Piperacillin | >64 | 16 | 1 |

| Cephalothin | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| Cefazolin | 16 | 8 | 1 |

| Cefuroxime | 8 | 16 | 4 |

| Ceftazidime | 64 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Cefepime | 32 | ≤0.06 | ≤0.06 |

| Moxalactam | >64 | 2 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 4 | 2 | 0.12 |

| Meropenem | 16 | 1 | ≤0.06 |

| Aztreonam | >64 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

The susceptibility of DH5α containing only the plasmid vector is also shown for comparison.

Although the blaCAU-1 gene was expressed under the control of a Plac promoter in DH5α(pFG2003) (see text), IPTG was not added to the medium since the promoter is leaky under the conditions of in vitro susceptibility testing and expression was only marginally enhanced by the inducer.

These results confirmed that the C. crescentus CC2139 product is actually a metallo-β-lactamase and that it is produced in the original host even without β-lactam exposure. The enzyme encoded by the type strain (DSM4727T) was named CAU-1, and its determinant was named blaCAU-1. C. crescentus exhibited low overall susceptibility to β-lactams (Table 1). However, the fact that we also obtained high MICs of compounds that are poorly or not hydrolyzed by CAU-1 (e.g., aztreonam, ceftazidime, and cefepime [see below]) indicates the existence of additional β-lactam resistance mechanisms in this species.

Purification and biophysical characterization of the CAU-1 metallo-β-lactamase.

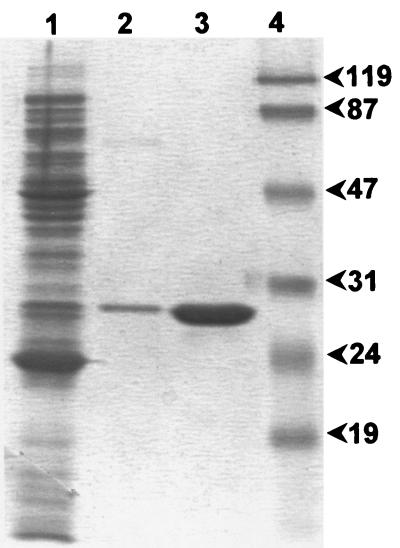

The CAU-1 enzyme was purified from a lysate of E. coli DH5α(pFG2003) by means of two ion-exchange chromatography steps with a final yield of approximately 10 mg/liter of culture. The purification process is summarized in Table 2. In repeated experiments, expression and purification of the enzyme exhibited good reproducibility (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Summary of a typical procedure for purification of the CAU-1 metallo-β-lactamase produced by E. coli DH5α(pFG2003)

| Product of purification step | Vol (ml) | Total protein (mg) | Total activity (U)a | Sp act (U/mg of protein) | Recovery (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extract | 5 | 52 | 890 | 17 | 100 | 1 |

| DEAE-Sepharose eluate | 15 | 5.4 | 542 | 100 | 61 | 5.9 |

| Sephadex G-25 eluate | 21 | 5.2 | 537 | 103 | 60 | 6.1 |

| Source 15S eluate | 7.5 | 1.2 | 158 | 132 | 18 | 7.8 |

One unit of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme hydrolyzing 1 μmol of meropenem per min under the conditions described in Materials and Methods.

On SDS-PAGE, the purified CAU-1 preparation revealed the presence of a single polypeptide with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 30 kDa and was estimated to be >95% pure (Fig. 3). The molecular mass of the purified enzyme, estimated by size exclusion chromatography, was approximately 30 kDa, indicating that the native enzyme is monomeric. The amino-terminal sequence was determined to be NH2-DDMPA, indicating that the mature enzyme was generated by the cleavage of a 21-amino-acid signal peptide. Electrospray mass spectrometry yielded a value of 28,768 ± 8 Da, in excellent agreement with the calculated molecular mass of the mature protein (28,762.6 Da).

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the purified CAU-1 protein (10 μg, lane 3), of the DEAE-Sepharose eluate (lane 2), and of the crude extract of DH5α(pFG2003) (lane 1). Protein molecular size standards (lane 4) are reported in kilodaltons on the right.

Kinetic properties of the CAU-1 enzyme.

Analysis of the kinetic parameters of CAU-1 with several β-lactam substrates revealed that the enzyme was able to hydrolyze penicillins, carbapenems, narrow-spectrum cephalosporins, and moxalactam quite efficiently (kcat/Km ratios, >105 M−1 · s−1), while oxyimino cephalosporins (e.g., cefepime) were poorly or not hydrolyzed and aztreonam was not hydrolyzed (Table 3). In competition experiments with ampicillin, no inhibition was detectable with aztreonam (up to a concentration of 1 mM) while an inhibition constant (Ki) of 120 ± 10 μM was measured for cefepime (Table 3). Analysis of the Dixon plot indicated that the latter compound acted as a competitive inhibitor (data not shown). Interestingly, the Km values of the enzyme for the various substrates were notably and uniformly high, compared to those of other metallo-β-lactamases of subclass B3, indicating rather low affinities. In particular, this was also true with meropenem, a substrate that is well recognized by other members of subclass B3 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters of the purified CAU-1 metallo-β-lactamase and comparison with kcat/Km ratios of other enzymes of subclass B3a

| Drug | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) |

kcat/Km (μM−1 · s−1)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAU-1 | L1 | GOB-1 | FEZ-1 | |||

| Benzylpenicillin | 180 | 400 | 0.45 | 21 | 1.9 | 0.11 |

| Ampicillin | 220 | 440 | 0.5 | 4.4 | —b | 0.011 |

| Carbenicillin | 520 | 2,250 | 0.23 | 1.4 | — | — |

| Piperacillin | 65 | 115 | 0.57 | 7 | 1.7 | 0.012 |

| Cephalothin | 140 | 330 | 0.43 | — | 0.067 | 2.5 |

| Cefazolin | 100 | 340 | 0.3 | — | — | — |

| Cefuroxime | >14 | >1,000 | 0.014 | 2.7 | 0.98 | 6.6 |

| Ceftazidime | >0.95 | >400 | 0.002 | — | 0.76 | 0.004 |

| Cefepime | NHc | 120d | NDe | 0.019 | 0.2 | 0.006 |

| Moxalactam | >55 | >500 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| Nitrocefinf | 95 | 200 | 0.49 | 2.9 | — | 0.9 |

| Imipenem | 220 | 1,100 | 0.2 | 0.66 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Meropenem | 180 | 700 | 0.26 | 4.5 | 5.3 | 0.5 |

| Aztreonam | NH | >1,000 | ND | — | — | <10−2 |

Data for the S. maltophilia L1 enzyme are from reference 13. Data for benzylpenicillin, imipenem, piperacillin, cefepime, and meropenem are from reference 12. Data for the C. meningosepticum GOB-1 enzyme are from reference 3. Data for the L. gormanii FEZ-1 enzyme are from reference 25. The experimentally determined parameters are the means of three measurements. Standard deviations were always lower than 10%.

—, not reported.

NH, no hydrolysis detected.

Ki value, measured as described in Materials and Methods.

ND, not determined.

Substrate inhibition was observed with nitrocefin at concentrations higher than 500 μM.

The substrate profile of CAU-1, which showed a preference for some β-lactam substrates (e.g., penicillins, carbapenems, and some cephalosporins), while others (e.g., oxyimino cephalosporins) were poorly or not hydrolyzed and possibly acted as inhibitors, appeared to be significantly different from those of other enzymes of subclass B3 (Table 3), underscoring the functional heterogeneity that can be encountered among members of this lineage. The relatively low affinity shown for the various β-lactam substrates represents another unique feature of this enzyme. A similar finding was never encountered in other biochemically characterized enzymes of this class, which, although demonstrating various affinities for different β-lactams, always exhibited high affinity for some of them (Table 3).

Inactivation by divalent ion chelators.

The CAU-1 enzyme was efficiently inactivated by EDTA and o-phenanthroline, and pseudo-first-order inactivation rates (kis) were measured. However, in the ranges of concentrations tested (1 to 10 mM with EDTA and 0.1 to 0.5 mM with o-phenanthroline), the ki values remained independent of the chelator concentration and were similar (1.9 × 10−3 ± 0.2 × 10−3 s−1 for EDTA and 2.5 × 10−3 ± 0.3 × 10−3 s−1 for o-phenanthroline). This behavior suggested that, as already observed with L1 and FEZ-1 (5, 25), the chelators may act by scavenging the free metal. In this model, the ki value would represent the rate of dissociation of the Zn enzyme into the apoenzyme and free metal.

Structural comparison of the CAU-1 enzyme with other metallo-β-lactamases of subclass B3.

CAU-1 could be aligned over the entire sequences of other subclass B3 metallo-β-lactamases without introducing major gaps. The closest similarity (35.1% identical residues) was observed with the J. lividum THIN-B enzyme, although it is notably shorter than THIN-B. CAU-1 is slightly more divergent from the S. maltophilia L1 enzyme (32.9% identity), from the L. gormanii FEZ-1 enzyme (32.3% identity), and from the C. meningosepticum GOB-1 enzyme (30.7% identity) (Fig. 2).

Compared to L1, whose three-dimensional structure has been solved (36), the major characteristics of CAU-1 consist of (i) a shorter N terminus, which lacks a counterpart for residues in L1 that are important for tetramerization (Leu-26 and Leu-29) and might explain, at least in part, the monomeric structure of CAU-1; (ii) two single-residue insertions (Asn-88 and His-150a) and a six-residue insertion before helix H5 (from position 279 to position 284; similar to FEZ-1 and GOB-1); and (iii) notable variability in loop 2, although the overall length is the same (Fig. 2). All of the residues known to be involved in metal binding in the L1 enzyme (His-116, His-118, Asp-120, His-121, His-196, and His-263) are conserved in CAU-1 (Fig. 2), which also contains a serine residue at position 221 similar to the other subclass B3 enzymes (except GOB-1) and unlike enzymes of molecular subclasses B1 and B2 (15). Interestingly, the two cysteine residues (at positions 256 and 290) involved in the disulfide bridge present in L1 (36), and probably also in FEZ-1 (25) and THIN-B, are not conserved in CAU-1. In the latter enzyme, however, there are two cysteine residues (at positions 200 and 220) that might form a disulfide bridge between the loop preceding strand S10 and that following strand S11, which could be located very close to the active site (Fig. 2).

Genetic environment of the blaCAU determinant.

Analysis of the genetic environment of CC2139 in the chromosome of strain CB15 revealed that the metallo-β-lactamase determinant is bracketed by three other genes in an operon-like structure that comprises four overlapping ORFs, with blaCAU in the third position (Fig. 1). The product of the first ORF (CC2141) exhibits sequence similarity to transcriptional regulators of the ArsR family (Protein family accession no. PF01022; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Pfam/index.shtml) at its amino terminus and to S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases (Protein family accession no. PF01209) at its carboxy terminus. Homologs of this gene are present in the genomes of some Rhizobiaceae, including Mesorhizobium loti, Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and Sinorhizobium meliloti, and also in those of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Xylella fastidiosa (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/Entrez/genom_table_cgi). The product of the second ORF (CC2140) exhibits notable similarity to the MetF family of bacterial methylenetetrahydrofolate reductases (Protein family accession no. PF02219) (e.g., 52% identity with the MetF enzyme of M. loti and 45% identity with the corresponding enzyme of E. coli). The product of the fourth ORF (CC2138) exhibits notable similarity to the amino-terminal methyltransferase domain of the MetH family of bacterial cobalamin-dependent methionine synthases (Protein family accession no. PF02574) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, CC2138 is followed by a 177-bp sequence that includes a long, imperfect palindrome, after which there is another ORF (CC2137) that encodes a homolog to the carboxy-terminal cobalamin-binding domain of the MetH family (27).

PCR mapping was used to analyze the structure of this region in the genome of strain DSM 4727T. Amplification experiments with primers OP-CAU/F and OP-CAU/R, designed to amplify the 4.6-kb chromosomal region containing the cluster of four genes (Fig. 1), were unsuccessful under our experimental conditions. However, with the same primers in combination with internal primers (CAU-OP/F with CAU-MET/R and BLA-CAU/F with CAU-OP/R), two amplicons of the expected sizes (3.3 and 2.2 kb, respectively) were obtained (Fig. 1). The restriction profiles of these amplicons (with HincII, NcoI, and PvuII for the 2.2-kb amplicon and with HinfI, PstI, and RsaI for the 3.3-kb amplicon) were consistent with the reported sequence (Fig. 1), suggesting that, in the type strain, the organization of the chromosomal locus surrounding blaCAU-1 is very similar to that in CB15.

blaCAU-1 is the first example of a metallo-β-lactamase determinant embedded in a similar genetic environment. The significance of this finding remains to be clarified. However, the fact that some of the other genes clustered in that operon are likely involved in the methionine biosynthesis pathway raises the possibility that CAU-1 is also involved in some related metabolic pathway. Investigation of this point is currently in progress.

Concluding remarks.

Identification of new members of known protein families by a postgenomic approach is an increasingly common practice. In this work, we confirmed the orthologous nature of a putative metallo-β-lactamase gene that is present in the chromosome of C. crescentus. The enzyme, named CAU-1, is a new member of the highly divergent subclass B3 lineage of metallo-β-lactamases that exhibits some unique functional properties.

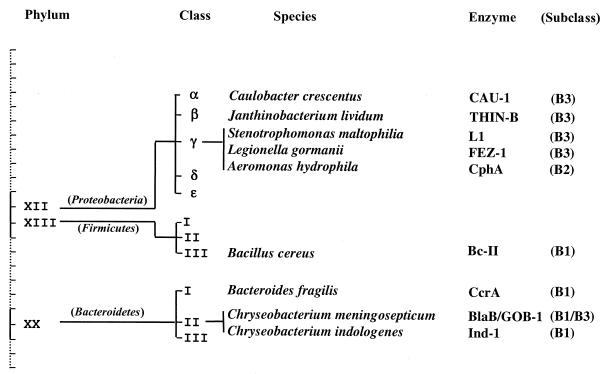

CAU-1 represents the first resident metallo-β-lactamase found in a member of the α subdivision of the class Proteobacteria (Fig. 4), increasing the repertoire of environmental species that produce similar enzymes. Virtually all of the resident metallo-β-lactamases were found to be produced in organisms that synthesize at least one other β-lactamase (9, 24). In the genome of C. crescentus, there is an ORF (CC0575) encoding a putative class C serine β-lactamase (27) but sequence comparisons showed that its product is highly divergent from other enzymes of this class (identity, ≤25%), while the elements typical of these enzymes (17) are not fully conserved. Should this gene not be an ortholog in this group, C. crescentus would represent the first exception to this observation.

FIG. 4.

Distribution of resident metallo-β-lactamases in bacterial lineages. Only phyla in which such enzymes have been detected are shown, along with the corresponding species. Bacterial classification is according to Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (16).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the European research network on metallo-β-lactamases within the “Training and Mobility of Researchers” (TMR) Program (contract FMRX-CT98-0232) and by grant 20011068755_003 (PRIN 2001) from the Italian “M.I.U.R.”

Thanks are due to Isabel Garcia-Saez for N-terminal protein sequencing and mass spectrometry data and to Emanuela Dell'Amico for excellent assistance in DNA sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm, E. W., D. B. Oerther, N. Larsen, D. A. Stahl, and L. Raskin. 1996. The oligonucleotide probe database. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:3557-3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambler, R. P. 1980. The structure of β-lactamases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 289:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellais, S., D. Aubert, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 2000. Molecular and biochemical heterogeneity of class B carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases in Chryseobacterium meningosepticum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1878-1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellais, S., S. Léotard, L. Poirel, T. Naas, and P. Nordmann. 1999. Molecular characterization of a carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamase from Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) indologenes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 171:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bicknell, R., E. L. Emanuel, J. Gagnon, and S. G. Waley. 1985. The production and molecular properties of the zinc β-lactamase of Pseudomonas maltophilia IID 1275. Biochem. J. 229:791-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boschi, L., P. S. Mercuri, M. L. Riccio, G. Amicosante, M. Galleni, J. M. Frère, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. The Legionella (Fluoribacter) gormanii metallo-β-lactamase: a new member of the highly divergent lineage of molecular-subclass B3 β-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 44:1538-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bush, K. 1999. β-Lactamases of increasing clinical importance. Curr. Pharm. Des. 5:839-845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bush, K. 1998. Metallo-β-lactamases: a class apart. Clin. Infect. Dis. 27:S48-S53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bush, K., G. A. Jacoby, and A. A. Medeiros. 1995. A functional classification scheme for β-lactamases and its correlation with molecular structure. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1211-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Meester, F., B. Joris, G. Reckinger, C. Bellefroid-Bourguignon, J. M. Frère, and S. G. Waley. 1987. Automated analysis of enzyme inactivation phenomena. Application to β-lactamases and DD-peptidases. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36:2393-2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ely, B., and C. J. Gerardot. 1988. Use of pulse-field gradient gel electrophoresis to construct a physical map of the Caulobacter crescentus genome. Gene 68:323-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felici, A., and G. Amicosante. 1995. Kinetic analysis of extension of substrate specificity with Xanthomonas maltophilia, Aeromonas hydrophila, and Bacillus cereus metallo-β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:192-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felici, A., G. Amicosante, A. Oratore, R. Strom, P. Ledent, B. Joris, L. Fanuel, and J.-M. Frère. 1993. An overview of the kinetic parameters of class B β-lactamases. Biochem. J. 291:151-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franceschini, N., B. Caravelli, J. D. Docquier, M. Galleni, J. M. Frère, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Purification and biochemical characterization of the VIM-1 metallo-β-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3003-3007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galleni, M., J. Lamotte-Brasseur, G. M. Rossolini, J. Spencer, O. Dideberg, and J. M. Frère. 2001. Standard numbering scheme for class B β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:660-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrity, G. M., M. Winters, and D. B. Searles. 2001. Taxonomic outline of the procaryotic genera, p. 1-26. In G. M. Garrity (ed.), Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology, 2nd edition. Springer-Verlag, New York, N.Y.

- 17.Goffin, C., and J. M. Ghuysen. 1998. Multimodular penicillin-binding proteins: an enigmatic family of orthologs and paralogs. Microb. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1079-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagel, J. 1989. Protein purification. Principles, high resolution methods, and applications, p. 63-106. VCH Publishers Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 19.Hussain, M., A. Carlino, M. J. Madonna, and J. O. Lampen. 1985. Cloning and sequencing of the metallothioprotein β-lactamase II gene of Bacillus cereus 569/H in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 164:223-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, J. L. 1994. Similarity analysis of DNAs, p. 655-682. In P. Gerhardt, R. G. E. Murray, W. A. Wood, and N. R. Krieg (ed.), Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laraki, N., N. Franceschini, G. M. Rossolini, P. Santucci, C. Meunier, E. de Pauw, G. Amicosante, J.-M. Frère, and M. Galleni. 1999. Biochemical characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa 101/1477 metallo-β-lactamase IMP-1 produced by Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:902-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lauretti, L., M. L. Riccio, A. Mazzariol, G. Cornaglia, G. Amicosante, R. Fontana, and G. M. Rossolini. 1999. Cloning and characterization of blaVIM, a new integron-borne metallo-β-lactamase gene from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1584-1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livermore, D. M., and N. Woodford. 2000. Carbapenemases: a problem in waiting? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:489-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercuri, P. S., F. Bouillenne, L. Boschi, J. Lamotte-Brasseur, G. Amicosante, B. Devreese, J. van Beeumen, J. M. Frère, G. M. Rossolini, and M. Galleni. 2001. Biochemical characterization of the FEZ-1 metallo-β-lactamase of Legionella gormanii ATCC 33297T produced in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1254-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.NCCLS. 2000. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A5. NCCLS Wayne, Pa.

- 27.Nierman, W. C., T. V. Feldblyum, M. T. Laub, I. T. Paulsen, K. E. Nelson, J. Eisen, J. F. Heidelberg, M. R. Alley, N. Ohta, J. R. Maddock, I. Potocka, W. C. Nelson, A. Newton, C. Stephens, N. D. Phadke, B. Ely, R. T. DeBoy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, M. L. Gwinn, D. H. Haft, J. F. Kolonay, J. Smit, M. B. Craven, H. Khouri, J. Shetty, K. Berry, T. Utterback, K. Tran, A. Wolf, J. Vamathevan, M. Ermolaeva, O. White, S. L. Salzberg, J. C. Venter, L. Shapiro, and C. M. Fraser. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4136-4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rasmussen, B. A., and K. Bush. 1997. Carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:223-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riccio, M. L., N. Franceschini, L. Boschi, B. Caravelli, G. Cornaglia, R. Fontana, G. Amicosante, and G. M. Rossolini. 2000. Characterization of the metallo-β-lactamase determinant of Acinetobacter baumannii AC-54/97 reveals the existence of blaIMP allelic variants carried by gene cassettes of different phylogeny. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:1229-1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rossolini, G. M., M. A. Condemi, F. Pantanella, J. D. Docquier, G. Amicosante, and M. C. Thaller. 2001. Metallo-β-lactamase producers in environmental microbiota: new molecular class B enzyme in Janthinobacterium lividum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:837-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossolini, G. M., N. Franceschini, M. L. Riccio, P. S. Mercuri, M. Perilli, M. Galleni, J.-M. Frère, and G. Amicosante. 1998. Characterization and sequence of the Chryseobacterium (Flavobacterium) meningosepticum carbapenemase: a new molecular class B β-lactamase showing a broad substrate profile. Biochem. J. 332:145-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossolini, G. M., T. Walsh, and G. Amicosante. 1996. The Aeromonas metallo-β-lactamases: genetics, enzymology, and contribution to drug resistance. Microb. Drug Resist. 2:245-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 34.Segel, I. H. 1975. Enzyme kinetics, behavior and analysis of rapid equilibrium and steady-state enzyme systems, p. 210-212. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 35.Tsao, S. G., C. F. Brunk, and R. E. Pearlman. 1983. Hybridization of nucleic acids directly in agarose gels. Anal. Biochem. 131:365-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ullah, J. H., T. R. Walsh, I. A. Taylor, D. C. Emery, C. S. Verma, S. J. Gamblin, and J. Spencer. 1998. The crystal structure of the L1 metallo-β-lactamase from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia at 1.7 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 284:125-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh, T. R., L. Hall, S. J. Assinder, W. W. Nichols, S. J. Cartwright, A. P. MacGowan, and P. M. Bennett. 1994. Sequence analysis of the L1 metallo-β-lactamase from Xanthomonas maltophilia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1218:199-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, Z., W. Fast, A. M. Valentine, and S. J. Benkovic. 1999. Metallo-β-lactamase: structure and mechanism. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:614-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]