Abstract

We have previously shown that a series of nonnucleoside pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines selectively inhibit the replication of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). These compounds act at the immediate-early or early stage of HCMV replication and have antiviral properties somewhat similar to those of roscovitine and olomoucine, specific inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks). In the present study we examine the hypothesis that pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines exert their antiviral effects by inhibition of cellular cdks. Much higher concentrations of a panel of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine nucleoside analogs with antiviral activity were required to inhibit recombinant cdk1/cyclin B compared to the submicromolar concentrations required to inhibit HCMV and HSV-1 replication. 4,6-Diamino-5-cyano-7-(2-phenylethyl)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (compound 1369) was the best inhibitor of cdk1 and cyclin B, with a 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50; 14 μM) similar to that of roscovitine; it was competitive with respect to ATP (Ki = 14 μM). The potency of compound 1369 against cdk1 and cyclin B was similar to its cytotoxicity (IC50s, 32 to 100 μM) but not its antiviral efficacy (IC50s, 0.02 to 0.3 μM). Thus, our results indicated the null hypothesis. In contrast, roscovitine was only weakly active against HSV-1 (IC50, 38 μM) and HCMV (IC50, 40 μM). These values were similar to those derived by cytotoxicity and cell growth inhibition assays, thereby suggesting that roscovitine is not a selective antiviral. Therefore, we propose that inhibition of cdk1 and cyclin B is not responsible for selective antiviral activity and that pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines constitute novel pharmacophores which compete with ATP to inhibit cdk1 and cyclin B.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (HSV-1) and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) are important human pathogens (2). Diseases caused by these viruses are treated with nucleoside analogs (ganciclovir and cidofovir) and foscarnet, which share a common molecular target: viral DNA polymerase (13). With the exception of the antisense phosphorothioate oligonucleotide fomivirsen (37), clinical resistance to these drugs has emerged (14). Consequently, there is a need for new therapeutics with molecular targets distinct from those inhibited by the drugs already on the market. Toward this goal, we have described a series of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine nucleoside analogs that contain a number of compounds (Fig. 1) with potent and selective inhibitory activities against HSV-1 and/or HCMV (24-26, 41-45, 51). Time-of-addition and time-of-removal studies have established that these multiplicity of infection-dependent compounds act early or very early in the viral replication cycle, after entry into the cell but before activation of viral DNA polymerase activity (20).

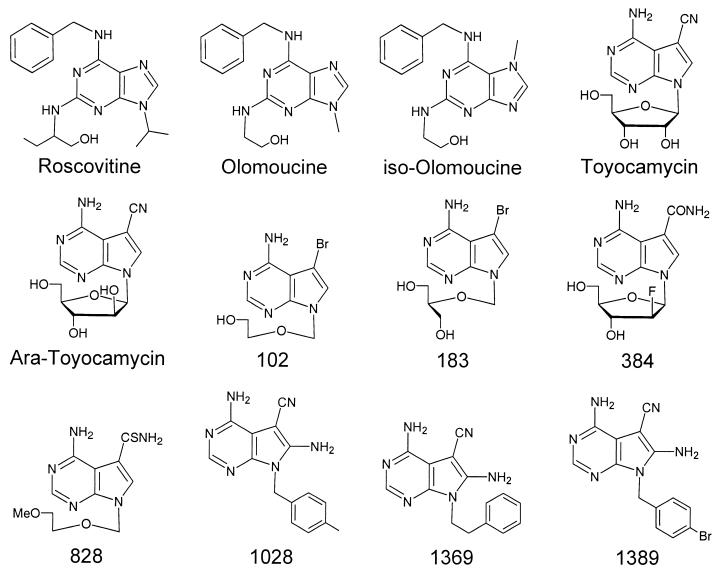

FIG. 1.

Structures of the substituted purine and pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines used in this study. The compounds were purchased or were synthesized as described in Materials and Methods.

It has been advanced that the replication of HSV and HCMV requires G1-specific, cell cycle regulatory cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) (3-6, 22, 46-48). Arrest of the cell cycle just past the G1 restriction point could make available an abundance of macromolecular precursors that these herpesviruses require for replication. This involves the release of E2 factor (E2F) transcription factors from the inhibitory E2F-Rb (Rb represents the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product) complex by mechanisms including the actions of cdk2/cyclin E (for a review, see reference 34). This model is supported by the association of HSV (19) and HCMV (4) infection with the activation of cdk2/cyclin E and the synchronization of HCMV- and HSV-infected cells in G1/S (3, 12). Indeed, the major immediate-early proteins of HCMV have been shown to play a role in cell cycle progression through G1. For example, IE1p72 phosphorylates specific E2Fs and pocket proteins (29, 36) and relieves p107-mediated suppression of an E2F-responsive promoter (38). IE2p86 has been shown to induce G1 arrest in transfected cells (53), to bind to Rb (15), to act as a transcription factor for cyclin E (6), to block the protein cdk inhibitors Cip1 and Kip1 (3), and to relieve Rb-mediated suppression of E2F- and thymidine kinase-specific genes (29). Similarly, immediate-early HSV proteins have been shown to interact with cell cycle regulatory cdks, E2Fs, or Rb and pocket proteins. ICP0 binds to and stabilizes cyclin D3, maintaining the function of cdk4 (23), and its expression blocks cells at the G1/S border (27). ICP22 and the UL13 gene product have been shown to activate cdk1 (1).

These interactions between immediate-early promiscuous transactivating viral proteins and cellular cell cycle-specific proteins are analogous to those seen in DNA tumor viruses. Simian virus 40, adenovirus, and human papillomavirus express gene products (large T antigen, E1A, and E7, respectively) which appear to upregulate cell cycle progression by binding to and sequestering Rb (33, 35).

However, there are indications that the interaction of viral proteins with cdk cell cycle regulation is not canonically established. As an alternative, it has been reported that HCMV IE1p72 cannot relieve Rb-mediated suppression of an E2F-responsive promoter (38). HCMV IE2p86 has been shown to be insufficient to induce cyclin E (30) and to halt cell cycle progression independently of Rb, p53, and Cip1 (53). Greaves and Mocarski (17) have propagated a fibroblast cell line stably expressing physiologically relevant levels of the IE1p72 protein through multiple cell cycles, which indicates that the expression of this protein is insufficient to induce cell cycle arrest, a finding confirmed by others (7). Cells infected with HCMV (21) and HSV (1) have been shown to synchronize in G2/M phase, in contrast to G1/S phase. It has also been demonstrated that HSV replicates independently of the mammalian cell cycle (8, 9). Nonetheless, Schaffer and coworkers (22, 46-48) propose a specific requirement for cdks in HSV replication based upon the inhibitory effects of roscovitine, a purine analog being evaluated as an anticancer agent (32).

Roscovitine is a protein kinase inhibitor specific for cdks 1, 2, and 5; and its potencies against these enzymes are equal, regardless of their regulatory cyclin subunits (11). Roscovitine is inactive against some 40 other cellular kinases examined (11). Schaffer and coworkers (22, 46-48) have shown that roscovitine inhibits HSV-1 replication at all stages of the lytic viral life cycle at concentrations sufficient to synchronize cells in S phase. The inability of those investigators to isolate virus resistant to roscovitine pointed toward a mechanism of action in which the inhibition of cellular cdks was responsible for antiviral activity (46). Likewise, Albrecht and coworkers (4) have demonstrated that roscovitine inhibits HCMV replication. Although the antiviral effects of roscovitine were clearly demonstrated in the previous studies, the cytotoxicity controls used in those studies did not clearly establish selective inhibition of these viruses in the absence of detrimental effects to host cells.

Consistent with the previous investigators' inability to select HSV isolates resistant to roscovitine (46), we have been unable to select HCMV isolates resistant to the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine nucleoside analogs used in this study (20). Furthermore, some compounds in this series have previously been described as cellular kinase inhibitors; e.g., sangivamycin inhibits protein kinase C (28), and toyocamycin inhibits cdk1 (31). Also consistent with a mechanism of action not involving a nucleic acid polymerase, pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines do not require phosphorylation to exhibit antiviral activity (43). On the basis of the information presented above, we have evaluated the hypothesis that pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines exert their antiviral effects in a manner similar to that by which roscovitine exerts its antiviral effects, namely, by inhibition of cdks.

(Portions of the work in this paper were reported at the 13th International Conference on Antiviral Research, Baltimore, Md., April 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Compounds.

Roscovitine, olomoucine, and iso-olomoucine were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines were synthesized in the laboratories of L. B. Townsend as described elsewhere (24-26, 41-45, 51). Descriptions of the synthesis of 4,6-diamino-5-cyano-7-(2-phenylethyl)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (compound 1369) and 4,6-diamino-5-cyano-7-(4-bromobenzyl)pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine (compound 1389) will be reported elsewhere. Stock solutions of all compounds were prepared at 10 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Cell culture procedures.

Vero cells (transformed African green monkey kidney cells) were a kind gift from A. Oveta Fuller. KB, BSC-1, Vero, MRC-5 (primary human lung fibroblast), and primary human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells were routinely grown and passaged in monolayer cultures with minimal essential medium (MEM) with either Hanks or Earle salts supplemented with 10% calf serum or 10% fetal bovine serum (HFF and MRC-5 cells). The sodium bicarbonate concentration was varied to meet the buffering capacity required. Cells were passaged at 1:2 to 1:4 dilutions by conventional procedures by using 0.05% trypsin plus 0.02% EDTA in HEPES-buffered saline.

Virological procedures.

Plaque-purified isolate Po of the Towne strain of HCMV was kindly provided by Mark Stinski, University of Iowa. The KOS strain of HSV-1 was provided by Sandra K. Weller, University of Connecticut. Stock HCMV was prepared by infecting HFF cells at a multiplicity of infection of <0.01 The numbers of PFU per cell were determined as detailed previously (51). High-titer HSV-1 stocks were prepared by infecting BSC-1 cells at a multiplicity of infection of <0.1, also as detailed previously (51). Virus titers were determined by using monolayer cultures of HFF cells for HCMV and monolayer cultures of BSC-1 cells for HSV-1, as described earlier (39).

HCMV plaque reduction assay.

HFF cells in 24-well cluster dishes were infected with approximately 100 PFU of HCMV per well by the procedures detailed above (51). Following virus adsorption, compounds dissolved in growth medium were added to duplicate wells at four to eight selected concentrations. After incubation at 37°C for 7 days, the cell sheets were fixed and stained with crystal violet, and microscopic plaques were enumerated as described above. The effects of the drugs were calculated as a percentage that indicated the percent reduction in the number of plaques in the presence of each drug concentration compared to the number observed in the absence of drug.

HSV-1 ELISA.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used (40) to detect HSV-1. Each well of 96-well cluster dishes was planted with 10,000 BSC-1 cells in 200 μl of MEM with Earle salts plus 10% calf serum. After overnight incubation at 37°C, selected drug concentrations in triplicate and HSV-1 at a concentration of 100 PFU/well were added. Following a 3-day incubation at 37°C, the medium was removed, the plates were blocked and rinsed, and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-HSV-1 antibody (P0175; DAKO) was added. Following removal of the antibody-containing solution, the plates were rinsed and then developed by adding to each well 150 μl of a solution of tetramethylbenzidine as the substrate. The reaction was quenched with H2SO4, and the absorbance was read at 450 and 570 nm. Drug effects were calculated as a percentage that consisted of the percent reduction in absorbance in the presence of each drug concentration compared to the absorbance obtained with virus in the absence of drug.

Cytotoxicity assays.

Two different assays were used to determine cytotoxicity. (i) The visual cytotoxicity produced in stationary HFF cells was determined by microscopic inspection of cells not affected by the virus used in the plaque assays. (ii) The effects of the compounds during two population doublings of KB cells were determined by staining the cells with crystal violet and spectrophotometrically quantitating the dye that eluted from stained cells. Briefly, 96-well cluster dishes were planted with KB cells at 3,000 to 5,000 cells per well. After incubation overnight at 37°C, the test compounds were added in triplicate at six to eight concentrations. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in a CO2 incubator, rinsed, fixed with 95% ethanol, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Acidified ethanol was added, and the plates were read at 570 nm in a spectrophotometer designed to read 96-well ELISA plates.

Data analysis.

Dose-response relationships were constructed by linearly regressing the percent inhibition derived as described above against log drug concentrations. Fifty-percent inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) were calculated from the regression lines. Samples containing positive controls (acyclovir for HSV-1, ganciclovir for HCMV, and 2-acetylpyridine thiosemicarbazone for cytotoxicity) were used in all assays.

Cell growth assay.

Cell growth assays were performed by planting subconfluent HFF, MRC-5, BSC-1, and Vero cells in 24-well plates with the indicated concentrations of drug. Control assays were performed by omission of the drug or incubation with an amount of dimethyl sulfoxide equal to that added in the well with the highest concentration of drug. The number of cells in each well was quantified at 24-h intervals by harvesting cells with trypsin plus EDTA (51) and enumerating the cells with a Coulter counter.

cdk1 and cyclin B assays.

Enzyme inhibition assays were performed as described by Meijer and Kim (31). One unit of recombinant cdk1 or cyclin B (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.) was added to the manufacturer's buffer with 6 μg of histone H1 type III S (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml in the absence of drug or in the presence of drug at one of at least six drug concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1,000 μM with bovine serum albumin at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml, and 2 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3,000 μCi/mmol; NEN, Boston, Mass.) to ATP at a concentration of 15 μM in a total volume of 25 μl. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min. Control experiments established that the reaction was linear with respect to time between 10 and 60 min. The reaction mixtures were spotted onto phosphocellulose filter paper circles (P81; Whatman) and prior to drying were washed (five times for 5 min each time) with 0.1% phosphoric acid (200 ml). The dried filter papers were transferred to vials, and the amount of bound label was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. Values for nonspecific controls lacking histone H1 (which bound no more than 5% of the label) were subtracted. Data are presented as the percent maximum activity in the absence of drug. Kinetic assays were performed similarly, and the concentration of ATP was varied. Conditions were established such that the reaction proceeded linearly with respect to time. The data presented were normalized for the specific activity of the enzyme.

RESULTS

Selection of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines for study.

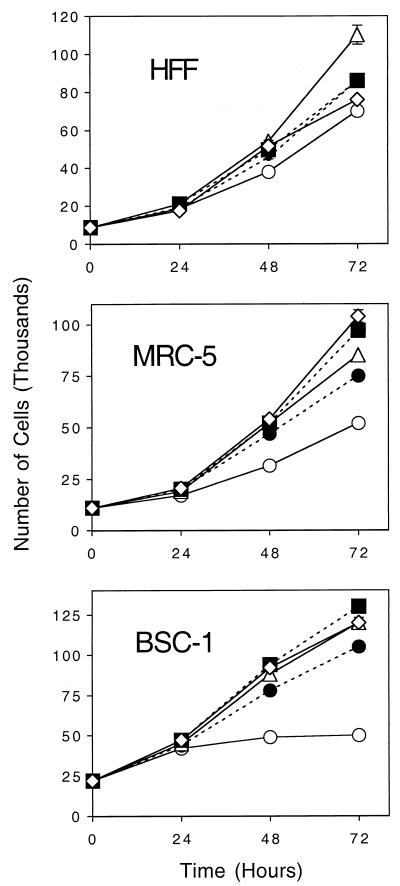

Compounds were selected for study on the basis of their antiviral activities and cytotoxicities. We have previously described many of these compounds and selected them because they all had potent activities against HCMV but different cytotoxicities (24-26, 41-45, 51) (Fig. 1). For example, toyocamycin was orders of magnitude more toxic than compound 828 (Table 1). Two new compounds, compounds 1369 and 1389, were also studied (Fig. 1). Both were active against HCMV at submicromolar concentrations, well below those that produced cytotoxicity (Table 1). Evaluation of the potential of compound 1369 to inhibit cell growth (Fig. 2) revealed that its inhibitory effects were seen only at concentrations which were orders of magnitude higher than those required for antiviral activity. Compound 1369 also was active against HSV-1. Thus, active compounds from this series had a range of in vitro selectivity indices, ranging from <1 for toyocamycin to nearly 200 for compounds 828 and 1369.

TABLE 1.

Antiviral activities, cytotoxicities, and inhibition of cdk by substituted purines and pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines

| Compound | IC50 (μM)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antiviral activitya

|

Cytotoxocity in cellsb

|

cdk1/cyclin Bc | |||

| HCMV | HSV-1 | HFF | KB | ||

| Toyocamycine | 0.1 | NDd | 0.03 | 0.03 | 65 ± 16 |

| Ara-toyocamycine | 1.7 | 38 | 8 | 17 | 268 |

| 102e | 3.9 | 16 | 100 | 100 | 225 |

| 183e | 1.5 | 1.8 | 100 | 3 | 260 |

| 384e | 0.025 | 0.47 | 5.5 | 1.9 | 44 ± 5 |

| 828e | 1.0 | 85 | >100 | 183 | 128 |

| 1028e | 0.3 | 60 | 32 | 100 | >359 |

| 1369 | 0.017 ± 0.007 | 0.3 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 | 32 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 |

| 1389 | 0.17 ± 0.05 | >100 | >10 | 15 ± 0 | >291 |

| Roscovitine | 40 ± 10 | 38 ± 7 | 31 ± 1 | 20 ± 0 | 5 ± 1 |

| Olomoucine | >100 | >100 | ≥100 | 85 ± 15 | 24 ± 4 |

| iso-Olomoucine | >100 | >100 | >100 | >100 | >1,000 |

| Ganciclovir | 2.5 | ND | >100 | ND | ND |

| Acyclovir | ND | 2.5 | ND | >320 | ND |

Antiviral assays were performed by a plaque assay for HCMV and an ELISA for HSV-1. Experiments were performed at least in duplicate, and the results are presented as means ± standard deviations. Data (means) for the first seven compounds have been published previously (see footnote e) and are presented here for comparison.

Visual cytotoxicity for stationary-phase HFF cells was scored at the time of HCMV plaque enumeration. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations of at least duplicate experiments. Inhibition of KB cell growth was determined in triplicate analyses. Data (means) for the first seven compounds have been published previously (see footnote e) and are presented here for comparison.

cdk1/cyclin B inhibition assays were performed independently six times for roscovitine, olomoucine, iso-olomoucine, and compound 1369. Compound 384 and toyocamycin were assayed in triplicate.

ND, not determined.

FIG. 2.

Effect of compound 1369 on cell growth. Cells (12,000 to 20,000 per well) were planted in 24-well plates and incubated with the indicated concentrations of compound 1369 or no drug. The number of cells per well was enumerated at 24-h intervals by use of a Coulter counter. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations of duplicate experiments. Concentrations of compound 1369 of 0 μM (⋄), 0.1 μM (▪), 1.0 μM (▵),10 μM (•), and 30 μM (○) were tested.

Inhibition of cdk.

The pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine series displayed various levels of activity against cdk, ranging from moderate to no inhibition (Table 1). Also, there was little correlation between enzyme inhibition and antiviral activity or cytotoxicity. For example, toyocamycin was highly cytotoxic but was only a weak inhibitor of the enzyme, and compound 1028 was active against HCMV and inactive as a cdk1 inhibitor. Thus, it is unlikely that inhibition of cdk1 and cyclin B is a general mechanism of action against HCMV and/or HSV-1 or cytotoxicity for the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines.

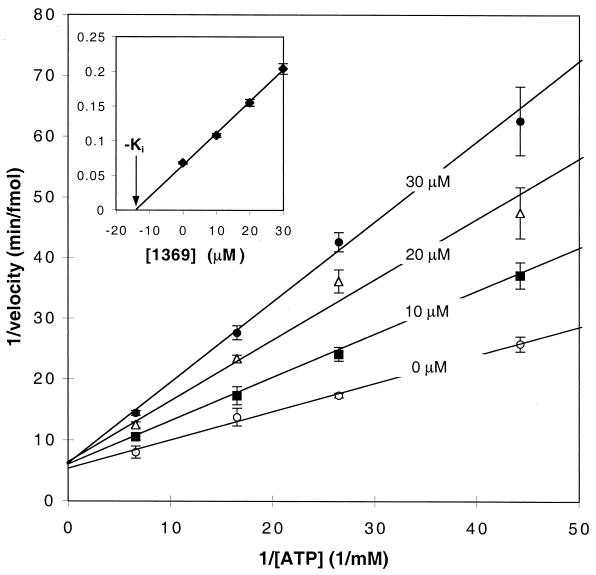

Compound 1369 was the best inhibitor in this series, with an IC50 (14 μM) between those of the positive control compounds roscovitine and olomoucine. iso-Olomoucine is a known inactive isomer of olomoucine (52) and served as a negative control for these experiments. In a separate series of experiments, we determined that compound 1369 is a competitive inhibitor of cdk1 and cyclin B, with a Ki of 14 μM (Fig. 3). Control experiments were consistent with reports that roscovitine is also a competitive inhibitor with respect to ATP, displaying an IC50 of 9 μM in our assays (data not shown). This places compound 1369 within a chemically diverse set of small-molecule cdk inhibitors which to date have all been reported to be competitive inhibitors with respect to ATP (16, 49).

FIG. 3.

Double-reciprocal plots of kinetic inhibitory data from assays of cdk1/cyclin B protein kinase with different concentrations of compound 1369. Enzyme activities were assayed in pentuplicate. The ATP concentration in the reaction mixture was varied from 24 to 160 μM; the concentration of histone H1 was kept constant at 1.2 μg/μl. The inset shows a secondary plot of the slopes from the primary plot against the concentration of compound 1369. The negative of the apparent inhibition constant (Ki) is shown with an arrow.

Antiviral activities of purine analogs.

We evaluated the purine analogs roscovitine, olomoucine, and iso-olomoucine for their activities against HSV-1 and HCMV. Plaque reduction assays revealed little or no inhibition of virus by olomoucine and iso-olomoucine at concentrations up to 100 μM, whereas roscovitine had an IC50 of 40 μM for HCMV (Table 1). Interestingly, the dose-response curve for roscovitine was precipitous, showing no inhibition of virus at concentrations up to 20 μM and complete inhibition at concentrations at and above 50 μM. Scoring for visual cytotoxicity revealed that the IC50 of roscovitine was 31 μM. The purine analogs were also evaluated for their activities against HSV-1. Consistent with results reported by Schaffer and coworkers (46), olomoucine and iso-olomoucine had IC50s greater than 100 μM and roscovitine had an IC50 of 38 μM. Cytotoxicity assays were performed with KB cells (Table 1) and showed that roscovitine inhibited cell growth at an IC50 of 20 μM, whereas olomoucine inhibited cell growth at an IC50 of 85 μM. This is consistent with reports that breast cancer cells underwent extensive apoptotic cell death in 28 μM roscovitine (32) and that 25 μM roscovitine reproducibly killed half of the MCF-7 cell populations within 24 h, as measured by trypan blue exclusion (10). Comparison of the concentrations of roscovitine and olomoucine required to inhibit HCMV and HSV with their cytotoxicities (Table 1) suggests that these purine analogs are at least as cytotoxic as they are antiviral and therefore do not possess selective antiviral activity. Similar to our results, Zimmermann et al. (54) reported that the concentration of roscovitine required to inhibit HCMV (IC50, ∼14 μM) was equal to that required to demonstrate cytotoxicity (IC50, ∼15 μM).

Cytotoxicity of roscovitine.

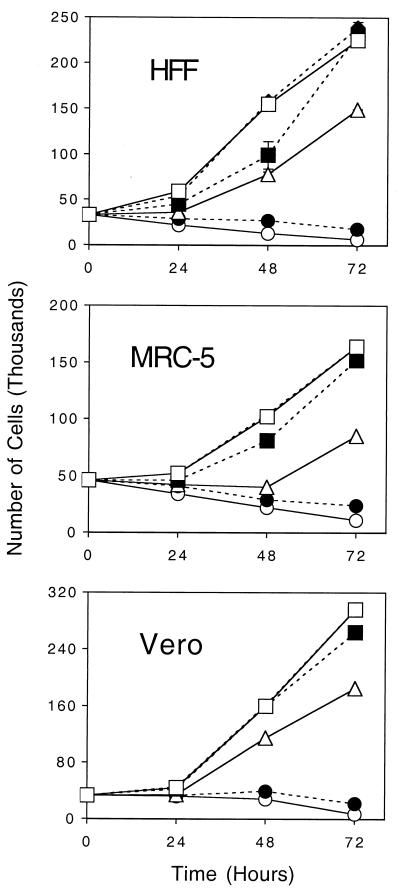

It has been reported that Vero cells tolerate 120 μM roscovitine (46) and that human lung fibroblasts cells tolerate 15 μM roscovitine (4) without evidence of alteration of the cellular morphology by visual inspection under a light microscope. Another study has determined that mouse leukemia L1210 cells (Y8 cell line) are not viable in the presence of 60 μM roscovitine due to the induction of caspase-3-like activity (50). In order to more carefully examine the cytotoxic effects of roscovitine, we performed cell growth experiments with four cell lines commonly used in assays for the activities of drugs against HSV and HCMV: BSC-1, Vero, HFF, and MRC-5 cells. Dose-dependent inhibition of growth of Vero, HFF, and MRC-5 cells was demonstrated at concentrations up to and including 11 μM (Fig. 4). However, at concentrations required for antiviral activity (33 to 100 μM), all cell lines exhibited evidence of extensive cell death. It was apparent that the remaining number of cells in the presence of 100 μM roscovitine was similar among the cell lines, with approximately 10% of cells remaining in wells containing 100 μM roscovitine after 4 days. Similar results were obtained with BSC-1 cells (data not shown). We conclude that the concentrations of roscovitine required to produce antiviral activity closely match those that elicit cytotoxicity for the four cell lines.

FIG. 4.

Effect of roscovitine on cell growth. Cells (40,000 to 50,000 per well) were planted in 24-well plates and incubated with the given concentrations of roscovitine, no drug, or an amount of dimethyl sulfoxide equivalent to the highest concentration tested. The number of cells per well was enumerated at 24-h intervals by use of a Coulter counter. Data are presented as the means ± standard deviations of duplicate experiments. Concentrations of roscovitine of 0 μM (♦), 3.7 μM (▪), 11 μM (▵), 33 μM (•), 100 μM(○) were tested. □, dimethyl sulfoxide control

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the hypothesis that the mechanism of antiviral action of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines was via the inhibition of a cellular cdk. Our data best support the null hypothesis. In contrast to reports of the selective antiviral activity of the cdk inhibitor roscovitine (4, 46-48), we have determined that the concentrations of this compound that were necessary to inhibit HSV-1 and HCMV were indistinguishable from those that produced cytotoxicity. Perhaps the intimate connection between the antiviral activity and cytotoxicity of roscovitine determined in this study can resolve the absence of specificity of this compound for any stage of the viral replication cycle (48). Considering that there are 1,000 to 2,000 ATP-requiring enzymes in a mammalian cell (49) and that roscovitine has been evaluated against only 40 of them, it is not necessarily valid that roscovitine, being an inhibitor of cdks, must exert its antiviral (and anticellular) activity by the inhibition of these cell cycle-regulating enzymes. Indeed, Russo and coworkers (32) have proposed other possible cellular targets for roscovitine, such as cell adhesion molecules.

The IC50s for cdk1 and cyclin B reported here indicate that roscovitine and olomoucine are slightly less potent than they were reported to be elsewhere (IC50s, 0.7 and 7 μM, respectively) (11, 31, 52). We propose three reasons for this discrepancy. First, since our reactions were started by the addition of enzyme, we did not preincubate the enzyme with an inhibitor. Second, our enzyme source was different: we purchased recombinant cdk1 and cyclin B, whereas the other investigators purified them from starfish oocytes. Third, in contrast to other researchers, we ran our assays with 100 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml. Considering these differences in methodology, it may be that compound 1369 has slightly greater potency against cdk1 and cyclin B than that which we have determined.

Although our results have not established a mode of antiviral action for pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines, we have determined a likely mechanism for the cytotoxicity of at least one of these compounds and discovered that the pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine pharmacophore is a competitive inhibitor of a cdk. A number of other heterocyclic compounds have been reported to be inhibitors of cdks (18). Together with a prior report on toyocamycin (31), these results establish pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines as another class of cdk inhibitors. In addition, the studies described herein suggest that inhibition of cellular cdks should be used with caution as a target for selective antiviral action.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant U19-AI-31718 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and research funds from the University of Michigan. D.L.E. gratefully acknowledges NIH training grant GM07767 for generous support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Advani, S. J., R. Brandimarti, R. R. Weichselbaum, and B. Roizman. 2000. Disappearance of cyclins A and B and the increase in activity of G2/M-phase cellular kinase cdc2 in herpes simplex virus 1-infected cells require expression of the α22/US1.5 and UL13 viral genes. J. Virol. 74:8-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alford, C. A., and W. J. Britt. 1993. Cytomegalovirus, p. 227-255. In B. Roizman, R. J. Whitley, and C. Lopez (ed.), The human herpesviruses. Raven Press, New York, N.Y.

- 3.Breshnahan, W. E., I. Boldogh, E. A. Thompson, and T. Albrecht. 1996. Human cytomegalovirus inhibits cellular DNA synthesis and arrests productively infected cells in late G1. Virology 224:150-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breshnahan, W. E., I. Boldogh, P. Chi, E. A. Thompson, and T. Albrecht. 1997. Inhibition of cellular cdk2 activity blocks human cytomegalovirus replication. Virology 231:239-247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breshnahan, W. E., E. A. Thompson, and T. Albrecht. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus infection results in altered cdk2 subcellular localization. J. Gen. Virol. 78:1993-1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breshnahan, W. E., E. A. Thompson, and T. Albrecht. 2082. 1998. The cyclin E promoter is activated by human cytomegalovirus 86-kDa immediate early protein. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22075-22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castillo, J. P., A. D. Yurochko, and T. F. Kowalik. 2000. Role of human cytomegalovirus immediate-early proteins in cell growth control. J. Virol. 74:8028-8037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen, G. H., R. K. Vaughan, and W. C. Lawrence. 1971. Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis in synchronized KB cells infected with herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 7:783-791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen, G. H. 1972. Ribonucleotide reductase activity of synchronized KB cells infected with herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. 9:408-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.David-Pfeuty, T. 1999. Potent inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 induce nuclear accumulation of wild-type p53 and nucleolar fragmentation in human untransformed and tumor-derived cells. Oncogene 18:7409-7422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Azvedo, W. F., S. Leclerc, L. Meijer, L. Havlicek, M. Strnad, and S.-H. Kim. 1997. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by purine analogs: crystal structure of human cdk2 complexed with roscovitine. Eur. J. Biochem. 243:518-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dittmer, D., and E. S. Mocarski. 1997. Human cytomegalovirus infection inhibits G1/S transition. J. Virol. 71:1629-1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erice, A. 1999. Resistance of human cytomegalovirus to antiviral drugs. Clin. Microbiol. 12:286-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Field, A. K., and K. K. Biron. 1994. “The end of innocence” revisited: resistance of herpesviruses to antiviral drugs. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 7:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fortunato, E., M. Sommer, K. Yoder, and D. Spector. 1997. Identification of domains within the human cytomegalovirus major immediate-early 86-kilodalton protein and the retinoblastoma protein required for physical and functional interaction with each other. J. Virol. 71:8176-8185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray, N., L. Detivaud, C. Doerig, and L. Meijer. 1999. ATP-site directed inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Curr. Med. Chem. 6:859-876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greaves, R. F. M., and E. S. Mocarski. 1998. Defective growth correlates with reduced accumulation of a viral DNA replication protein after low-multiplicity of infection by a human cytomegalovirus ie1 mutant. J. Virol. 72:366-379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardcastle, I. R., B. T. Golding, and R. J. Griffin. 2002. Designing inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42:325-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hossain, A., T. Holt, J. Ciacci-Zanella, and C. Jones. 1997. Analysis of cyclin-dependent kinase activity after herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. J. Gen. Virol. 78:3341-3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobson, J. J., T. E. Renau, M. R. Nassiri, D. G. Sweier, J. M. Breitenbach, L. B. Townsend, and J. C. Drach. 1999. Nonnucleoside pyrrolopyrimidines with a unique mechanism of action against human cytomegalovirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:1888-1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jault, F. M., J.-M. Jault, F. Ruchti, E. A. Fortunato, C. Clark, J. Corbeil, D. D. Richman, and D. H. Spector. 1995. Cytomegalovirus infection induces high levels of cyclins, phosphorylated Rb, and p53, leading to cell cycle arrest. J. Virol. 69:6697-6704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jordan, R. L., L. Schang, and P. A. Schaffer. 1999. Transactivation of herpes simplex type 1 immediate-early gene expression by virion-associated factors is blocked by an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J. Virol. 73:8843-8847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawaguchi, Y., C. Van Sant, and B. Roizman. 1997. Herpes simplex virus 1 α regulatory protein ICP0 interacts with and stabilizes the cell cycle regulator cyclin D3. J. Virol. 71:7328-7336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krawczyk, S. H., M. Bernier-Rodriguez, M. R. Nassiri, E. R. Kern, L. L. Wotring, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1990. Arabinofuranosylpyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines as potential agents for human cytomegalovirus infections. J. Med. Chem. 33:3160-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krawczyk, S. H., T. E. Renau, M. R. Nassiri, A. C. Westerman, L. L. Wotring, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1995. Synthesis and evaluation of certain thiosangivamycin analogs as potential inhibitors of cell proliferation and human cytomegalovirus. J. Med. Chem. 38:4115-4119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krawczyk, S. H., M. R. Nassiri, L. S. Kucera, E. R. Kern, R. G. Ptak, L. L. Wotring, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1995. Synthesis and antiproliferative and antiviral activity of 2′-deoxy-2′-fluoroarabinofuranosyl analogs of the nucleoside antibiotics toyocamycin and sangivamycin. J. Med. Chem. 38:4106-4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lomonte, P., and R. D. Everett. 1999. Herpes simplex virus type 1 immediate-early protein Vmw110 inhibits progression of cells through mitosis and from G1 into S phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol. 73:9456-9467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loomis, C. R., and R. M. Bell. 1988. Sangivamycin, a nucleoside analog, is a potent inhibitor of protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 283:1682-1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margolis, M., S. Pajovic, E. Wong, M. Wade, R. Jupp, J. Nelson, and J. C. Azizkhan. 1995. Interaction of the 72-kilodalton human cytomegalovirus IE1 gene product with E2F1 coincides with E2F-dependent activation of dihydrofolate reductase transcription. J. Virol. 69:7759-7767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McElroy, A. K., R. S. Dwarakanath, and D. H. Spector. 2000. Dysregulation of cyclin E gene expression in human cytomegalovirus-infected cells requires early viral gene expression and is associated with changes in the Rb-related protein p130. J. Virol. 74:4192-4206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meijer, L., and S.-H. Kim. 1997. Chemical inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases. Methods Enzymol. 283:113-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mgbonyebi, O. P., J. Russo, and I. H. Russo. 1999. Roscovitine induces cell death and morphological changes indicative of apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 59:1903-1910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moran, E. 1993. DNA tumor virus transforming proteins and the cell cycle. Curr. Opin. Genes Dev. 3:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nevins, J. R. 1999. Toward an understanding of the functional complexity of E2F and retinoblastoma families. Cell Growth Diff. 9:585-593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nevins, J. R. 1992. E2F: a link between the Rb tumor suppressor protein and viral oncoproteins. Science 258:424-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pajovic, S., E. Wong, A. Black, and J. C. Azizkhan. 1997. Identification of a viral kinase that phosphorylates specific E2Fs and pocket proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6459-6464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perry, C. M., and J. A. Barman Balfour. 1999. Fomivirsen. Drugs 57:375-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poma, E., T. Kowalik, L. Zhu, J. Sinclair, and E.-S. Huang. 1996. The human cytomegalovirus IE1-72 protein interacts with the cellular p107 protein and relieves p107-mediated transcriptional repression of an E2F-responsive promoter. J. Virol. 70:7867-7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prichard, M. N., S. R. Turk, L. A. Coleman, S. L. Englehardt, C. Shipman, Jr., and J. C. Drach. 1990. A microtiter virus yield reduction assay for the evaluation of antiviral compounds against human cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus. J. Virol. Methods 28:101-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prichard, M. N., L. E. Prichard, W. A. Baguley, M. R. Nassiri, and C. Shipman, Jr. 1991. Three-dimensional analysis of the synergistic cytotoxicity of ganciclovir and zidovudine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1060-1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pudlo, J. S., N. K. Saxena, M. R. Nassiri, S. R. Turk, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1988. Synthesis and antiviral activity of certain 4- and 4,5-disubstituted 7-[(2-hydroxyethoxy)methyl]pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. J. Med. Chem. 31:2086-2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pudlo, J. S., M. R. Nassiri, E. R. Kern, L. L. Wotring, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1990. Synthesis, antiproliferative, and antiviral activity of certain 4-substituted and 4,5-disubstituted 7-[(1,3-dihydroxy-2-propoxy)methyl]pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. J. Med. Chem. 33:1984-1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Renau, T. E., M. R. Nassiri, E. E. Swayze, L. B. Townsend, and J. C. Drach. 1998. Design, synthesis, and activity against human cytomegalovirus of non-phosphorylatable analogs of toyocamycin, sangivamycin, and thiosangivamycin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2:1755-1760. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renau, T. E., L. L. Wotring, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1996. Synthesis of non-nucleoside analogs of toyocamycin, sangivamycin, and thiosangivamycin: influence of various 7-substituents on antiviral activity. J. Med. Chem. 39:873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Renau, T. E., C. Kennedy, R. G. Ptak, J. M. Breitenbach, J. C. Drach, and L. B. Townsend. 1996. Synthesis of non-nucleoside analogs of toyocamycin, sangivamycin, and thiosangivamycin: the effect of certain 4- and 4,6-substituents on the antiviral activity of pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidines. J. Med. Chem. 39:3470-3476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schang, L. M., J. Phillips, and P. A. Schaffer. 1998. Requirement for cellular cyclin-dependent kinases in herpes simplex virus replication and transcription. J. Virol. 72:5626-5637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schang, L. M., A. Rosenberg, and P. A. Schaffer. 1999. Transcription of herpes simplex virus immediate-early and early genes is inhibited by roscovitine, an inhibitor specific for cellular cyclin-dependent kinases. J. Virol. 73:2161-2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schang, L. M., A. Rosenberg, and P. A. Schaffer. 2000. Roscovitine, a specific inhibitor of cellular cyclin-dependent kinases, inhibits herpes simplex virus DNA synthesis in the presence of viral early proteins. J. Virol. 74:2107-2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sielecki, T., J. F. Boylan, P. A. Benfield, and G. L. Trainor. 2000. Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors: useful targets in cell cycle regulation. J. Med. Chem. 43:1-18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Somerville, L., and J. G. Cory. 2000. Enhanced roscovitine-induced apoptosis is mediated by a caspase-3-like activity in deoxyadenosine-resistant mouse leukemia L1210 cells. Anticancer Res. 20:3347-3356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turk, S. R., C. Shipman, Jr., M. R. Nassiri, G. Genzlinger, S. H. Krawczyk, L. B. Townsend, and J. C. Drach. 1987. Pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine nucleosides as inhibitors of human cytomegalovirus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:544-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vesely, J., L. Havlicek, M. Strnad, J. Blow, A. Donella-Deana, L. Pinna, D. S. Letham, J. Y. Kato, L. Detivaud, S. Leclerc, and L. Meijer. 1994. Inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinases by purine analogues. Eur. J. Biochem. 224:771-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wiebusch, L., and C. Hagemeier. 1999. Human cytomegalovirus 86-kilodalton IE2 protein blocks cell cycle progression in G1. J. Virol. 73:9274-9283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmermann, A., H. Wilts, M. Lenhardt, M. Hahn, and T. Mertens. 2000. Indolocarbazenes exhibit strong antiviral activity against human cytomegalovirus and are potent inhibitors of the pUL97 protein kinase. Antivir. Res. 48:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]