Abstract

CD18 hypomorph mice expressing reduced levels of the common β2 integrin chain develop aggravated Lyme carditis, compared to that developed by wild-type (WT) mice, upon infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. The enhancement of Lyme carditis in these mice is characterized by increased macrophage infiltration, correlating with augmented expression of the monocyte/macrophage chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1). The lack of CD18 results in the deficiency of all β2 integrins, i.e., CD11a/CD18 (LFA-1), CD11b/CD18 (Mac-1/CR3), CD11c/CD18 (p150,95/CR4), and CD11d/CD18. To determine the roles of the various β2 integrins in controlling the development of aggravated Lyme carditis, disease induction was analyzed in CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11c−/− mice. CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice, but not CD11b−/− mice, developed aggravated Lyme carditis after exposure to B. burgdorferi. Similarly to CD18 hypomorph mice, CD11c−/− mice expressed higher levels of MCP-1, compared to both WT and CD11a−/− mice, as determined by in vitro analysis of MCP-1 secretion by bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and in vivo analysis of MCP-1 mRNA expression in B. burgdorferi-infected hearts. On the other hand, CD11a deficiency was associated with heightened heart B. burgdorferi burden relative to that of WT mice. Overall, our results suggest that the increased severity of Lyme carditis in CD18 hypomorph mice is caused by deficiency in CD11a or CD11c, possibly via different mechanisms.

Lyme disease is an infectious disorder caused by the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi (9, 38), which is transmitted to humans by Ixodes ticks (23, 36). When the spirochete is inoculated into the skin, it establishes infection and then disseminates to other organs, such as the heart and joints, where it causes carditis and arthritis (37). Carditis usually appears several weeks after infection and is estimated to affect 2 to 8% of untreated patients (19). Arthritis develops months after infection, affecting 60% of untreated patients (39).

The ability of B. burgdorferi to induce inflammation has sparked a lot of research interest, leading to the identification of B. burgdorferi lipoproteins as components capable of inducing inflammation (29). B. burgdorferi lipoproteins engage Toll-like receptor 2, resulting in the production of inflammatory cytokines (21). However, more needs to be uncovered about the mechanisms utilized by B. burgdorferi to induce inflammation. Interestingly, recent studies indicate that chemokines play a more important role in Lyme disease than previously recognized. Heightened levels of the chemokines monocyte/macrophage chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) and CXC chemokine ligand 1/KC correlate with increased severity of Lyme disease in mice (8). This finding seems quite logical, since chemokines induce the extravasation and migration of immune cells into tissues. The process of the extravasation of leukocytes into infected tissues is generally considered to be dependent on the expression of β2 integrins on leukocytes (20).

C57BL/6 mice inoculated with live B. burgdorferi organisms develop Lyme arthritis and carditis at 2 to 4 weeks postinfection (4, 43), rendering the mouse an excellent model for the examination of Lyme carditis. We have previously reported that CD18 hypomorph mice, in which leukocytes express 2 to 16% of β2 integrins (44), develop Lyme arthritis and carditis (18). This result was unexpected, because inflammatory diseases arise as a consequence of leukocyte migration into B. burgdorferi-infected joint and heart tissues (5, 6), and β2 integrins appear to be crucial for this process (20). In addition, we have shown that CD18 hypomorph mice develop aggravated Lyme carditis with increased macrophage infiltration in the heart compared to that developed by wild-type (WT) mice. The main inflammatory cell in Lyme carditis has been reported to be the monocyte-macrophage and has been associated with the expression of the monocyte/macrophage chemoattractant MCP-1 in the heart (32). In agreement with this, B. burgdorferi-infected CD18 hypomorph mice were found to show increased expression of MCP-1 mRNA expression in the B. burgdorferi-infected heart (18). Collectively, our data suggest that the reduced expression of CD18/β2 integrins results in increased MCP-1 production and increased macrophage infiltration in the heart in response to B. burgdorferi infection, causing the aggravation of Lyme carditis.

All members of the β2 integrin family share the common β chain, CD18, that pairs with different α chains (CD11a to CD11d) to form LFA-1 (CD11a/CD18), Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18), p150,95 (CD11c/CD18), and CD11d/CD18. In the absence of either chain, the heterodimer becomes unstable and is degraded. Thus, reduced CD18 expression affects all four β2 integrins. To determine the relative importances of the individual β2 integrins in the control of Lyme carditis, mutant mice with null expression of CD11a (15, 24), CD11b (13), or CD11c (30) were infected with B. burgdorferi. Mice deficient in CD11d, the most recently discovered member of the β2 integrin family, were not available for study. We observed increased severities of Lyme carditis in CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice, but not in CD11b−/− mice, suggesting that the β2 integrins CD11a/CD18 and CD11c/CD18 play roles in the control of Lyme carditis. Interestingly, different mechanisms appear to mediate the increases in carditis severity in these mice, with CD11a−/− mice developing an increased B. burgdorferi burden and CD11c−/− showing increased levels of MCP-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

Low-passage-number (passage number, 2 to 4) cultures of the infectious B. burgdorferi N40 clone D10E9A1-E (kind gift of Jenifer Coburn) (11, 12) were used in all experiments. Spirochetes were grown in complete BSK-H medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) at 33°C until they reached mid-log phase (5 × 107 B. burgdorferi cells/ml). B. burgdorferi cell numbers were determined by dark-field microscopy.

Mice.

Male CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice at the F6 backcross generation onto the C57BL/6 background were bred at the Tufts University Division of Laboratory Animal Medicine from breeding pairs obtained from Daniel Bullard. Male CD11b−/− mice (B6.129S4-itgamtm1Myd) backcrossed more than 10 times onto the C57BL/6 background and age-matched WT C57BL/6 mice were purchased (The Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, Maine). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tufts University approved all procedures.

Four-week-old male mutant and WT mice were infected intradermally in the tibial area of both hind limbs with a total dose of 104 B. burgdorferi N40 cells per mouse. After infection, the development of arthritis in the mice was followed by measurement of ankle widths with a caliper (Mahr Federal, Providence, RI), and sera were collected once a week through tail bleeding. At 2 to 3 weeks postinfection, on the peak of Lyme disease (based on Lyme arthritis edema measurements [4, 43]), mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, and the heart and ankle tissues were harvested. In some experiments, the heart was cut longitudinally, and one half was used for histology (see “Histopathology” below), while the other half was used for DNA extraction (see “B. burgdorferi burden” below). In addition, some hearts were used for RNA extraction.

Histopathology.

Hearts were cut in half through bisections across the atria and ventricles, and one half of each heart was fixed in phosphate-buffered 4% formalin. After fixation, the tissue was embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and hematoxylin-eosin stained. Hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections were histopathologically scored for cellular infiltration in a blind fashion on a scale from 0 to 3 (33) (0, no inflammation; 1, mild inflammation with less than two small foci of infiltration; 2, moderate inflammation with two or more foci of infiltration; 3, severe inflammation with focal and diffuse infiltration covering a large area, with the difference between this score in our scale and that described in reference 33 being that we observed no necrosis of the myocardium).

DC challenged with B. burgdorferi and MCP-1 ELISA.

Dendritic cells (DC) from mutant and WT mice were generated via granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulation of mouse bone marrow, as described previously (25). After 10 days of growth in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-containing RPMI 10% fetal bovine serum medium, nonadherent DC were harvested, washed, and plated at 150,000 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture plates in 500 μl of RPMI 1640 10% fetal bovine serum supplemented with l-glutamine. After overnight rest, DC were challenged with various B. burgdorferi-DC ratios for 24 h, and supernatants were collected and tested for the presence of the chemokine MCP-1 by MCP-1 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

MCP-1 real-time reverse transcriptase PCR.

Half of the heart was frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately after the sacrifice of the mouse. The tissue was ground with a mortar and pestle cooled with dry ice, and RNA was extracted from the resulting ground tissue with Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The RNA was treated with DNase from a DNA-free kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) and reverse transcribed to cDNA by use of Superscript II/III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA was diluted to ratios of 1:200 and 1:10 for the 18S and MCP-1 amplifications, respectively. Twenty μl of the diluted cDNA was used as a template in the real-time reaction mixture, which contained 1× iTaq SYBR green Supermix with ROX (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and 0.3 μM of each primer. For the 18S amplification, the primers used were CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA and GCT GGAATTACCGCGGCT (2). For the MCP-1 amplification, the primers used were TTAACGCCCCACTCACCTGCTG and GCTTCTTTGGGACACCTGCTGC (2, 45). The amplifications, adapted from reference 2, were performed on an Applied Biosystem 5700 sequence detection system. The reactions were initiated by incubation at 95°C for 2 min, which was followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Data were analyzed with GeneAmp 5700 sequence detection system software, and the severalfold increases in expression relative to that of the uninfected WT sample were calculated and normalized to the expressions of the housekeeping gene, 18S, for all samples.

B. burgdorferi burden.

Collected heart tissue was minced with a razor blade and kept frozen at −20°C until processing. DNA was extracted by a modification of the method of Morrison et al. (28). The tissue (half heart) was incubated for 4 h at 37°C in 200 μl of 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline without Ca2+/Mg2+ (Cellgro, Herndon, VA). The same volume of lysis solution (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8, 5 mM EDTA, 0.2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 200 mM NaCl) containing 1 mg/ml proteinase K (Invitrogen) was then added, and the tissue was further incubated overnight at 55°C. The resulting solution was extracted twice with buffer-saturated phenol (Invitrogen) and once with phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol 25:24:1 (Invitrogen). The DNA was precipitated with 95% ethanol in the presence of 0.3 M sodium acetate, pH 5.5, and resuspended in PCR-quality water.

The B. burgdorferi chromosomal RecA and mouse nidogen genes were amplified by real-time PCR according to the method described by Morrison et al. (28), with the following modifications. The real-time amplifications were performed in 50-μl volumes containing iTaq SYBR green with ROX mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), 0.3 μM of each 5′ and 3′ RecA or nidogen primer, and 300 ng of sample with an Applied Biosystems 7300 sequence detection system. The amplifications were started by incubation at 95°C for 2 min and followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Data were analyzed with GeneAmp 7300 sequence detection system software and compared to standard curves for B. burgdorferi or mouse genomic DNA to calculate a RecA/nidogen ratio, representative of the number of B. burgdorferi genomes per mouse genome in the samples.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis to compare multiple experimental groups was performed through use of Bonferroni's multiple comparison or repeated measures test (one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]) or, for comparison between two groups only, through Student's two-tailed, unpaired equal-variance t test. The statistical analysis applied is indicated in the corresponding figure legend. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Increased Lyme carditis severity in CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice.

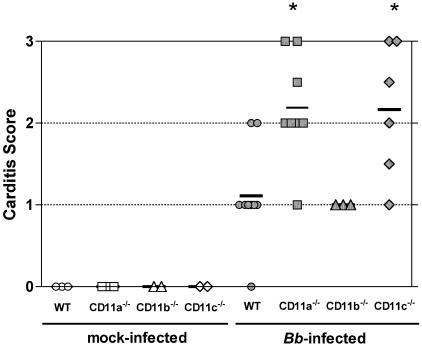

CD18 hypomorph mice develop aggravated Lyme carditis (18). In order to determine the contribution of the individual β2 integrin heterodimers CD11a/CD18, CD11b/CD18, and CD11c/CD18 to the control of Lyme carditis, we infected CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, CD11c−/−, and WT C57BL/6 mice with B. burgdorferi. The severities of Lyme carditis were analyzed at 3 weeks postinfection through histopathology analysis, representative of cellular infiltration. As shown in Fig. 1, hearts from uninfected WT, CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11c−/− mice showed no signs of cellular infiltration. B. burgdorferi infection resulted in the development of mild Lyme carditis in WT and CD11b−/− mice, with mean severity scores of 1.11 and 1.0, respectively. In contrast, B. burgdorferi-infected CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice developed aggravated carditis, with mean severity scores of 2.19 for CD11a−/− mice and 2.17 for CD11c−/− mice. These data indicate that deficiency of CD11a or CD11c results in an augmented severity of Lyme carditis, suggesting that the β2 integrins CD11a/CD18 and CD11c/CD18 contribute to the control of Lyme carditis.

FIG. 1.

Lyme carditis severity in CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11c−/− mice. Lyme carditis histopathology scores, as described in Materials and Methods, at 3 weeks postinfection for uninfected WT mice (open circles; n = 3), CD11a−/− mice (open squares; n = 2), CD11b−/− mice (open triangles; n = 2), and CD11c−/− mice (open diamonds; n = 2) and for B. burgdorferi (Bb)-infected WT mice (filled circles; n = 9), CD11a−/− mice (filled squares; n = 8), CD11b−/− mice (filled triangles; n = 3), and CD11c−/− mice (filled diamonds; n = 6) are depicted. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, and the averages are shown by the horizontal lines. Lyme carditis average scores ± standard deviations (SD) were 1.11 ± 0.6 for WT, 2.19 ± 0.6 for CD11a−/−, 1 ± 0 for CD11b−/−, and 2.17 ± 0.8 for CD11c−/− mice. The asterisks indicate that the differences between B. burgdorferi-infected WT and knockout mice are significant by one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni's multiple comparison) test (P < 0.01). Data include the pooled results of two independent experiments.

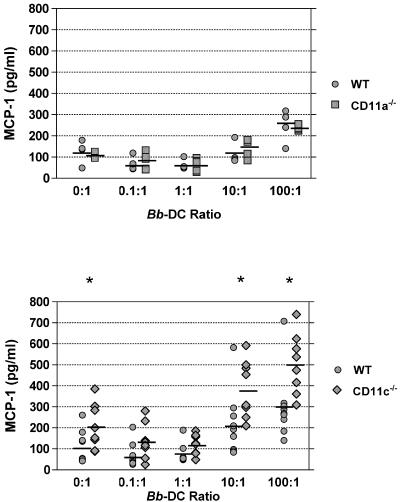

Increased MCP-1 secretion in bone marrow-derived DC from CD11c−/− mice.

The aggravated Lyme carditis in CD18 hypomorph mice is accompanied by increased macrophage infiltration and correlates with augmented secretion of the macrophage chemoattractant MCP-1 production by bone marrow-derived DC (18). The in vitro response of bone marrow-derived DC may mirror that of resident DC populations in the heart, which are key initiators of the immune reaction to infection via cytokine and chemokine production (10). To determine which β2 integrin heterodimer is responsible for the altered MCP-1 secretion in CD18 hypomorph DC, the amounts of MCP-1 secreted by WT and mutant DC exposed to B. burgdorferi for a 24-h period were analyzed. We observed that secretion of MCP-1 in DC from CD11a−/− (Fig. 2, top panel) or CD11b−/− (data not shown) mice was similar to that of WT mice at all B. burgdorferi/DC ratios tested. In contrast, twofold-higher production of MCP-1 was observed in DC from CD11c−/− mice compared to those from WT mice at the 10:1 and 100:1 B. burgdorferi/DC ratios (Fig. 2, bottom panel). These results indicate that the absence of CD11c/CD18 in CD18 hypomorph DC may be responsible for increased MCP-1 production in cells with reduced CD18 expression.

FIG. 2.

MCP-1 secretion by bone marrow-derived DC from CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice. (Top panel) Similar MCP-1 secretion levels in CD11a−/− and WT DC. MCP-1 secretion levels by bone-marrow derived DC from WT mice (filled circles; n = 4) and from CD11a−/− mice (filled squares; n = 4) at increasing ratios of B. burgdorferi (Bb) to DC are depicted. Supernatants obtained after 24-h incubations were assayed for MCP-1 by ELISA. The MCP-1 concentrations in the supernatant are shown, with each symbol corresponding to DC originated from bone marrow of one individual mouse and the horizontal lines corresponding to the average MCP-1 concentrations. There were no statistically significant differences between the levels of MCP-1 secretion from WT and CD11a−/− DC by unpaired unequal variance Student's t test (P = 0.37 to 0.99). (Bottom panel) Increased MCP-1 secretion in CD11c−/− DC. MCP-1 secretion by bone marrow-derived DC from WT mice (filled circles; n = 8) and CD11c−/− mice (filled diamonds; n = 8) at increasing ratios of B. burgdorferi to DC. Supernatants obtained after 24-h incubations were assayed for MCP-1 by ELISA. In the graphs, the MCP-1 concentrations in the supernatants are shown, with each symbol corresponding to DC originated from bone marrow of one individual mouse and each horizontal line corresponding to the average MCP-1 concentration. The difference between WT and CD11c−/− mice was statistically significant at ratios of 0:1, 10:1, and 100:1 (unpaired unequal variance Student's t test; P = 0.022 and 0.020 for 10:1 and 100:1 ratios, respectively), as indicated by the asterisks. Data from two independent experiments were combined.

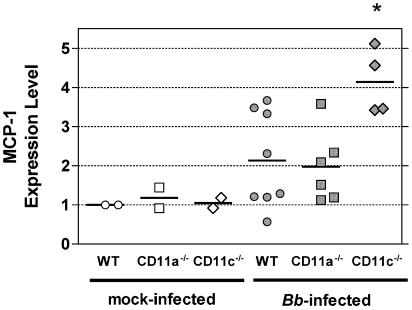

Increased expression of MCP-1 mRNA in the hearts of B. burgdorferi-infected CD11c−/− mice.

Next, it was important to resolve whether the augmented secretion of MCP-1 by DC observed in vitro translated to similarly altered expression of MCP-1 in vivo. To determine this, we analyzed expression of MCP-1 mRNA in hearts of mice at 3 weeks after infection with B. burgdorferi. We observed that MCP-1 was expressed at similar baseline levels in the hearts of uninfected WT, CD11a−/−, and CD11c−/− mice, with no significant difference observed between these groups (Fig. 3). Upon B. burgdorferi infection, MCP-1 expression was significantly up-regulated, with 2.1-, 1.9-, and 4.1-fold increases in the respective mice. Thus, the hearts of B. burgdorferi-infected CD11c−/− mice showed a 100% increase in MCP-1 RNA expression compared to those of infected WT or CD11a−/− mice (Fig. 3). These data demonstrate for the first time that hearts of B. burgdorferi-infected CD11c−/− mice, but not of CD11a−/− mice, express levels of MCP-1 mRNA higher than those of their WT counterparts, confirming the in vitro results obtained with bone marrow-derived DC. This set of results strongly suggests that increased MCP-1 production in CD11c−/− mice contributes to aggravated Lyme carditis. In contrast, aggravated Lyme carditis in CD11a−/− mice is not mediated by this mechanism.

FIG. 3.

Increased MCP-1 mRNA expression in hearts from B. burgdorferi (Bb)-infected CD11c−/− mice. RNA was isolated from hearts of WT, CD11a−/−, and CD11c−/− mice at 3 weeks after B. burgdorferi infection, and the transcripts for MCP-1 and 18S were amplified by real-time PCR. The level of expression of MCP-1 was calculated as a ratio of each sample relative to the value for one uninfected WT mouse sample and was normalized to the 18S expression in each sample. This calculation yields the relative MCP-1 expression levels shown in the graph. Uninfected WT mice (open circles; n = 2), CD11a−/− mice (open squares; n = 2), and CD11c−/− mice (open diamonds; n = 2) express MCP-1 at similar levels. Upon B. burgdorferi infection, MCP-1 was induced in WT mice (filled circles; n = 8; average ± SD, 2.1 ± 1.22) and CD11a−/− mice (filled squares; n = 6; average ± SD, 1.9 ± 0.9) to a lesser extent than in CD11c−/− mice (filled diamonds; n = 4; average ± SD, 4.1 ± 0.83). The average for each group is represented as a horizontal line. There were no significant differences between uninfected WT, CD11a−/−, and CD11c−/− mice. The difference in MCP-1 expression levels between B. burgdorferi-infected WT and CD11c−/− mice, but not between B. burgdorferi-infected WT and CD11a−/− mice, was statistically significant (one-way ANOVA [Bonferroni multiple comparison]; P < 0.01). The results shown correspond to samples pooled from two independent experiments, with each symbol representing one mouse.

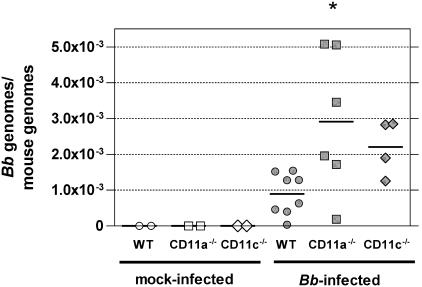

Increased B. burgdorferi burden in the hearts of CD11a−/− mice.

Another possible determinant of the severity of inflammation is B. burgdorferi burden. To determine whether the deficiency of either of two β2 integrins, CD11a/CD18 or CD11c/CD18, affected the control of B. burgdorferi infection and consequently Lyme carditis severity, we determined the B. burgdorferi burden in hearts harvested at 3 weeks postinfection. As shown in Fig. 4, CD11a−/− mice, but not CD11c−/− mice, had a significantly (3.3-fold) higher B. burgdorferi burden than WT mice, with average counts of 0.8 × 10−3 for WT and 2.9 × 10−3 for CD11a−/− mice. On the other hand, the B. burgdorferi burden was intermediately increased in CD11c−/− mice relative to that in WT mice, but the difference was not statistically significant.

FIG. 4.

Increased B. burgdorferi (Bb) burden in CD11a−/− mice. The graph depicts the number of B. burgdorferi genomes per mouse genome in the hearts of WT, CD11a−/−, and CD11c−/− mice at 3 weeks postinfection. The ratio of B. burgdorferi genomes to mouse genomes was determined based on the real-time PCR amplifications of the B. burgdorferi RecA gene and the mouse nidogen gene, respectively. The analysis was performed on samples from two independent experiments, all combined in the graph. No amplification of the RecA gene was observed in samples from uninfected WT (n = 2), CD11a−/− (n = 2), or CD11c−/− (n = 2) mice. Upon B. burgdorferi infection, B. burgdorferi could be detected in the hearts of all groups, with an average B. burgdorferi burden ± SD of 0.8 × 10−3 for WT, 2.9 × 10−3 for CD11a−/−, and 2.2 × 10−3 for CD11c−/− mice. The averages are depicted on the graph as horizontal lines. The difference between WT and CD11a−/− mice was statistically significant, as determined by one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni's multiple comparison), while there was no significant difference between WT and CD11c−/− mice.

Increased severity of Lyme arthritis in CD11c−/− mice.

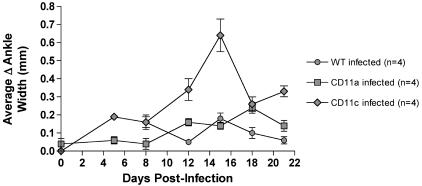

Although the reduced expression of β2 integrins in B. burgdorferi-infected CD18 hypomorph mice resulted in aggravated Lyme carditis, Lyme arthritis severity was not significantly increased compared to that for infected WT mice (18). To determine whether the role of CD11a and CD11c in the control of inflammation was specific to Lyme carditis or applied as well to Lyme arthritis, the development of Lyme arthritis was analyzed in B. burgdorferi-infected CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice. Lyme arthritis edema was followed over a 3-week time course in WT, CD11a−/−, and CD11c−/− mice simultaneously infected with B. burgdorferi. The severity of Lyme arthritis is represented as the change in average ankle width, calculated by subtracting the average value of ankle width for uninfected mice from the values for infected mice. The greater mildness of the Lyme arthritis observed in these experiments compared to that described in our previous report (18) may be due to the use of a different lot of commercial BSK-H medium for B. burgdorferi growth, which has been reported to influence the severity of disease (42). While WT and CD11a−/− mice developed mild arthritis, with similar changes in ankle width, CD11c−/− mice developed more-severe ankle swelling, peaking between days 12 and 18 (Fig. 5). Resolution started around day 18, but complete remission had not been achieved by day 21 postinfection, as represented by a remaining positive change in ankle width value. These results indicate that neither CD11a nor CD11c is required for the development of joint edema in Lyme arthritis. In addition, they suggest that CD11c may play a role in the control of Lyme arthritis edema.

FIG. 5.

Arthritis development in CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice. The graph depicts the variation in the average increase in ankle width (a measure of arthritis edema) over the course of the experiment in infected WT mice (filled circles; n = 4), CD11a−/− mice (filled squares; n = 4), and CD11c−/− mice (filled diamonds; n = 4). The change (Δ) in average ankle width was calculated by subtracting the average value of ankle width for uninfected mice from the value of infected mice. Both ankles were measured for each mouse. The standard errors of the mean are represented by error bars. No statistically significant differences were observed between WT and CD11a−/− mice. The difference between WT and CD11c−/− mice was statistically significant, as determined by one-way ANOVA (repeated measures test; P < 0.01). The results are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

CD18 hypomorph mice expressing reduced levels of all β2 integrins develop aggravated Lyme carditis (18). Here, we analyze the role of three of the β2 integrins, CD11a/CD18, CD11b/CD18, and CD11c/CD18, in controlling the severity of Lyme carditis. Analysis of Lyme carditis development in CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11c−/− mice uncovered that deficiency of CD11a and CD11c, but not of CD11b, results in increased severity of Lyme carditis relative to that of WT C57BL/6 mice. Deficiency of CD11a compromised the control of B. burgdorferi infection in the heart, while CD11c deficiency resulted in augmented MCP-1 expression in the heart, suggesting that different mechanisms mediate aggravated Lyme carditis in these mice.

In our previous study, we addressed the role of β2 integrins in the development of Lyme arthritis and carditis (18), which are consequences of the migration of immune cells into B. burgdorferi-infected joint and heart tissues (5, 6). This process is traditionally considered to depend on β2 integrins (20). However, it was observed that CD18 hypomorph mice developed not only levels of Lyme arthritis similar to those of WT mice but also aggravated Lyme carditis (18). Since CD18 hypomorph mice express low levels (2 to 16%) of β2 integrins on leukocytes (44), these results could be interpreted in two ways. Either a low level of expression of CD18 is sufficient for cell extravasation into the B. burgdorferi-infected heart and ankle tissues, or additional adhesion molecules contribute to this extravasation. Although the final answer to this question will likely be provided by the CD18 null mouse model, we have now analyzed the development of Lyme arthritis and/or carditis in CD11a−/−, CD11b−/−, and CD11c−/− mice expressing 0% of the corresponding β2 integrins on leukocytes (13, 15, 24, 30). None of these mutant mice had a defect in the development of Lyme arthritis or carditis, suggesting that the individual β2 integrins CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c are dispensable for the development of Lyme arthritis and/or carditis.

The aggravation of Lyme carditis in B. burgdorferi-infected CD18 hypomorph mice was an even more surprising result. In an effort to understand the mechanism underlying this phenomenon, we analyzed B. burgdorferi burdens, observing that CD18 hypomorph mice control B. burgdorferi burden similarly to WT. In contrast, CD18 hypomorph mice express aberrantly high levels of MCP-1 in B. burgdorferi-infected hearts. MCP-1 is a chemokine that primarily attracts monocytes, although it also attracts T cells, mast cells, and basophils, but not neutrophils (1, 31). The observed increase in MCP-1 is consistent with the increased macrophage infiltration observed in this tissue. The augmented production of MCP-1 was also observed in bone marrow-derived DC exposed to B. burgdorferi in vitro. This led to a model in which deficiency of CD18 increases the production of MCP-1 by heart-resident DC, possibly through a reduction in the ability of the DC to produce nitric oxide (NO), an inhibitor of MCP-1 production (41). We have now observed that deficiency of CD11a and/or CD11c reproduces the phenotype of aggravated Lyme carditis. Both CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice, originally on a 129 background, are at the F6 backcross generation, at which 98.44% of the genome is expected to be of C57BL/6 origin. This, together with the fact that mice of a 129 background develop mild Lyme disease in a manner similar to that of C57BL/6 mice (17), makes it unlikely that any remaining genes of a 129 background are responsible for the phenotype. Therefore, the increased Lyme carditis severity in CD18 hypomorph mice is likely caused by deficiency in CD11a or CD11c or by a composite of the effects of the CD11c and CD11a deficiencies.

Interestingly, the mechanisms by which CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice develop aggravated Lyme carditis appear to be different. When looking into possible mechanisms leading to aggravated Lyme carditis in CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice, we focused a great deal of interest on alterations in MCP-1 production for several reasons. On one hand, an alteration in MCP-1 production was previously observed in CD18 hypomorph mice (18). On the other hand, increases in MCP-1 production reportedly correlate with cardiac disease, as human patients with acute myocarditis show twofold increases in MCP-1 serum levels compared to healthy controls (16). In addition, there is direct evidence that the expression of MCP-1 in cardiac tissue results in the development of myocarditis, since mice transgenic for the MCP-1 gene under control of the α cardiac myosin heavy chain promoter develop myocarditis with macrophage infiltration (22). Finally, augmented MCP-1 expression has been observed in Lyme disease lesions from mouse strains that develop severe, as opposed to mild, Lyme disease (8). Our analysis of MCP-1 production by bone marrow-derived DC in CD11a−/− and CD11c−/− mice uncovered that deficiency of CD11c, but not of CD11a or CD11b, results in a twofold increase in B. burgdorferi-induced MCP-1 secretion. An MCP-1 mRNA increase was also observed in vivo in the B. burgdorferi-infected hearts of CD11c−/− mice. These results reproduce very closely the data obtained from CD18 hypomorph mice. Therefore, the alterations in MCP-1 secretion and mRNA expression in CD18 hypomorph mice are most likely due to CD11c deficiency.

On the other hand, the increased severity of Lyme carditis in CD11a−/− mice does not seem to be mediated by increased MCP-1 production, because CD11a−/− DC produced levels of MCP-1 that were normal compared to those produced by WT C57BL/6 mice. We have observed that CD11a−/− mice show a 3.3-fold increase in B. burgdorferi burden in the heart, which may mediate or contribute to aggravated Lyme carditis. Interestingly, CD11a/CD18 is the major neutrophil adhesion receptor in mice (15), and a decreased neutrophil response may lead to an increase in B. burgdorferi burden. We can speculate further about a role for T or NK cells in the control of Lyme carditis, since the function of these cells is known to be defective in CD11a−/− mice (26, 35). A protective role for T cells, specifically for the T helper 1 subset, in Lyme carditis is based on studies of RAG−/− and SCID mice, which develop nonresolving aggravated Lyme carditis (27, 34), and of αβ-T-cell-deficient mice, which develop chronic carditis that resolves upon transfer of gamma interferon-producing T helper 1 cells (7). Evidence that NK cells may play a role in control of Lyme carditis is provided by the NIH 3 immunodeficient mice. These mice, which share nu/nu, xid, and bg mutations and, therefore, lack B, T, and NK cells and granulocytes, develop increased Lyme carditis severity with pancarditis (14). Although not only NK cells are deficient in these mice, pancarditis was not observed in SCID or nude mice. Therefore, defective granulocyte and T and NK cell function in CD11a−/− mice may contribute to increased Lyme carditis severity via control of the B. burgdorferi burden or other mechanisms. Further studies may shed further light on the specific mechanism of the development of increased Lyme carditis severity in CD11a−/− mice.

In comparison to the results obtained with CD18 hypomorph, CD11a−/−, and CD11b−/− mice, CD11c−/− mice developed more-severe Lyme arthritis swelling. The reason for this difference is unknown. Cellular infiltration in the joint of B. burgdorferi-infected CD18 hypomorph mice was not significantly increased compared to that in WT, but a slight increase was observed (18). It is important to note that if CD11c actually plays a role in the control of Lyme arthritis severity, the phenotype may not have been as obvious in mice with hypomorphic versus null expression of this gene. Since CD11c deficiency results in increased MCP-1 production, these mice may develop Lyme arthritis infiltrates with increased numbers of macrophages.

Although these data suggest that the individual β2 integrins perform different roles during the pathogenesis of carditis in this mouse model, the specific functions of these adhesion molecules in human Lyme disease remain to be determined. Overall, the mouse and human β2 integrins show many similarities both in their expression patterns and in their functions during immune and inflammatory responses. For example, CD18 mutant mice and human leukocyte adhesion deficiency patients present with many of the same abnormalities, including increased susceptibility to mucocutaneous infections, impaired wound healing, increased peripheral blood leukocyte counts, and impaired neutrophil adhesion (3, 35, 44). However, several unique differences have been observed between the members of this adhesion molecule family in the two species. These include the absence of the ICAM-3 gene, which encodes a ligand for LFA-1, in the mouse; a stronger requirement for Mac-1 expression and function in the mediation of neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells in humans; and an apparent increase in the use of alternative non-β2 integrin adhesion pathways in the mouse for mediating neutrophil recruitment (15, 20, 40). Future studies are needed to investigate whether these differences may contribute to any specific alterations in the roles of these adhesion molecules during the development of Lyme disease in humans.

In summary, our study has identified a role for the β2 integrins CD11a/CD18 and CD11c/CD18 as integrins in the control of the severity of Lyme carditis. Although both integrin defects resulted in similar effects on Lyme carditis severity, this effect appeared to be mediated by distinct mechanisms. On one hand, our study has uncovered that CD11a/CD18 plays an important role in the control of B. burgdorferi infection. On the other hand, a deficiency in CD11c causes increased MCP-1 production by DC and increased expression of this chemokine in the B. burgdorferi-infected heart. These results suggest that the aggravated Lyme carditis observed in CD18 hypomorph mice is the result of the deficiency in CD11a/CD18 and/or CD11c/CD18.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIHRO1 AR45386, GRASP Center NIH/NIDDK, P30 DK34928, and the Eshe Fund.

Editor: J. B. Bliska

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, D. H., and A. R. Lloyd. 1997. Chemokines: leucocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet 349:490-495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akpek, E. K., D. A. Jabs, H. C. Gerard, R. A. Prendergast, A. P. Hudson, B. Lee, and J. A. Whittum-Hudson. 2004. Chemokines in autoimmune lacrimal gland disease in MRL/MpJ mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45:185-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson, D. C., and T. A. Springer. 1987. Leukocyte adhesion deficiency: an inherited defect in the Mac-1, LFA-1, and p150,95 glycoproteins. Annu. Rev. Med. 38:175-194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong, A. L., S. W. Barthold, D. H. Persing, and D. S. Beck. 1992. Carditis in Lyme disease susceptible and resistant strains of laboratory mice infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 47:249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthold, S., D. S. Beck, G. M. Hansen, G. A. Terwilliger, and K. D. Moody. 1990. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J. Infect. Dis. 162:133-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barthold, S. W., D. H. Persing, A. L. Armstrong, and R. A. Peeples. 1991. Kinetics of Borrelia burgdorferi dissemination and evolution of disease after intradermal inoculation of mice. Am. J. Pathol. 139:263-273. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockenstedt, L. K., I. Kang, C. Chang, D. Persing, A. Hayday, and S. W. Barthold. 2001. CD4+ T helper 1 cells facilitate regression of murine Lyme carditis. Infect. Immun. 69:5264-5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, C. R., V. A. Blaho, and C. M. Loiacono. 2003. Susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis correlates with KC and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 production in joints and requires neutrophil recruitment via CXCR2. J. Immunol. 171:893-901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgdorfer, W., A. G. Barbour, S. F. Hayes, J. L. Benach, E. Grunwaldt, and J. P. Davis. 1982. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science 216:1317-1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone, F. R., and W. R. Heath. 2003. The role of dendritic cell subsets in immunity to viruses. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15:416-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coburn, J., S. W. Barthold, and J. M. Leong. 1994. Diverse Lyme disease spirochetes bind integrin αIIbβ3 on human platelets. Infect. Immun. 62: 5559-5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coburn, J., J. M. Leong, and J. K. Erban. 1993. Integrin alpha IIb beta 3 mediates binding of the Lyme disease agent Borrelia burgdorferi to human platelets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:7059-7063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coxon, A., P. Rieu, F. J. Barkalow, S. Askari, A. H. Sharpe, U. H. von Andrian, M. A. Arnaout, and T. N. Mayadas. 1996. A novel role for the beta 2 integrin CD11b/CD18 in neutrophil apoptosis: a homeostatic mechanism in inflammation. Immunity 5:653-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Defosse, D. L., P. H. Duray, and R. C. Johnson. 1992. The NIH-3 immunodeficient mouse is a model for Lyme borreliosis myositis and carditis. Am. J. Pathol. 141:3-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding, Z. M., J. E. Babensee, S. I. Simon, H. Lu, J. L. Perrard, D. C. Bullard, X. Y. Dai, S. K. Bromley, M. L. Dustin, M. L. Entman, C. W. Smith, and C. M. Ballantyne. 1999. Relative contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to neutrophil adhesion and migration. J. Immunol. 163:5029-5038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fuse, K., M. Kodama, H. Hanawa, Y. Okura, M. Ito, T. Shiono, S. Maruyama, S. Hirono, K. Kato, K. Watanabe, and Y. Aizawa. 2001. Enhanced expression and production of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in myocarditis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 124:346-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glickstein, L., M. Edelstein, and J. Z. Dong. 2001. Gamma interferon is not required for arthritis resistance in the murine Lyme disease model. Infect. Immun. 69:3737-3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guerau-de-Arellano, M., J. Alroy, and B. T. Huber. 2005. Beta 2 integrins control the severity of murine Lyme carditis. Infect. Immun. 73:3242-3250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haddad, F. A., and R. B. Nadelman. 2003. Lyme disease and the heart. Front. Biosci. 8:s769-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris, E. S., T. M. McIntyre, S. M. Prescott, and G. A. Zimmerman. 2000. The leukocyte integrins. J. Biol. Chem. 275:23409-23412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschfeld, M., C. J. Kirschning, R. Schwandner, H. Wesche, J. H. Weis, R. M. Wooten, and J. J. Weis. 1999. Cutting edge: inflammatory signaling by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 163:2382-2386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolattukudy, P. E., T. Quach, S. Bergese, S. Breckenridge, J. Hensley, R. Altschuld, G. Gordillo, S. Klenotic, C. Orosz, and J. Parker-Thornburg. 1998. Myocarditis induced by targeted expression of the MCP-1 gene in murine cardiac muscle. Am. J. Pathol. 152:101-111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane, R. S., J. Piesman, and W. Burgdorfer. 1991. Lyme borreliosis: relation of its causative agent to its tick vectors and hosts in North America and Europe. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 36:587-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu, H., C. W. Smith, J. Perrard, D. Bullard, L. Tang, S. B. Shappell, M. L. Entman, A. L. Beaudet, and C. M. Ballantyne. 1997. LFA-1 is sufficient in mediating neutrophil emigration in Mac-1-deficient mice. J. Clin. Investig. 99:1340-1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lutz, M. B., N. Kukutsch, A. L. Ogilvie, S. Rossner, F. Koch, N. Romani, and G. Schuler. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto, G., M. P. Nghiem, N. Nozaki, R. Schmits, and J. M. Penninger. 1998. Cooperation between CD44 and LFA-1/CD11a adhesion receptors in lymphokine-activated killer cell cytotoxicity. J. Immunol. 160:5781-5789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKisic, M. D., and S. W. Barthold. 2000. T-cell-independent responses to Borrelia burgdorferi are critical for protective immunity and resolution of Lyme disease. Infect. Immun. 68:5190-5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morrison, T. B., Y. Ma, J. H. Weis, and J. J. Weis. 1999. Rapid and sensitive quantification of Borrelia burgdorferi-infected mouse tissues by continuous fluorescent monitoring of PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:987-992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Norgard, M. V., B. S. Riley, J. A. Richardson, and J. D. Radolf. 1995. Dermal inflammation elicited by synthetic analogs of Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins. Infect. Immun. 63:1507-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren, B., M. A. McCrory, C. Pass, D. C. Bullard, C. M. Ballantyne, Y. Xu, D. E. Briles, and A. J. Szalai. 2004. The virulence function of Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein A involves inhibition of complement activation and impairment of complement receptor-mediated protection. J. Immunol. 173:7506-7512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rollins, B. J. 1996. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1: a potential regulator of monocyte recruitment in inflammatory disease. Mol. Med. Today 2:198-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruderman, E. M., J. S. Kerr, S. R. R. Telford, A. Spielman, L. H. Glimcher, and E. M. Gravallese. 1995. Early murine Lyme carditis has a macrophage predominance and is independent of major histocompatibility complex class II-CD4+ T cell interactions. J. Infect. Dis. 171:362-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Satoskar, A. R., J. Elizondo, G. M. Monteforte, L. M. Stamm, H. Bluethmann, P. Katavolos, and S. R. Telford III. 2000. Interleukin-4-deficient BALB/c mice develop an enhanced Th1-like response but control cardiac inflammation following Borrelia burgdorferi infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 183: 319-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schaible, U. E., S. Gay, C. Museteanu, M. D. Kramer, G. Zimmer, K. Eichmann, U. Museteanu, and M. M. Simon. 1990. Lyme borreliosis in the severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mouse manifests predominantly in the joints, heart, and liver. Am. J. Pathol. 137:811-820. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scharffetter-Kochanek, K., H. Lu, K. Norman, N. van Nood, F. Munoz, S. Grabbe, M. McArthur, I. Lorenzo, S. Kaplan, K. Ley, C. W. Smith, C. A. Montgomery, S. Rich, and A. L. Beaudet. 1998. Spontaneous skin ulceration and defective T cell function in CD18 null mice. J. Exp. Med. 188:119-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spielman, A. 1994. The emergence of Lyme disease and human babesiosis in a changing environment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 740:146-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steere, A. C. 2001. Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:115-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steere, A. C., R. L. Grodzicki, A. N. Kornblatt, J. E. Craft, A. G. Barbour, W. Burgdorfer, G. P. Schmid, E. Johnson, and S. E. Malawista. 1983. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 308:733-740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steere, A. C., R. T. Schoen, and E. Taylor. 1987. The clinical evolution of Lyme arthritis. Ann. Intern. Med. 107:725-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugino, H. 2005. ICAM-3, a ligand for DC-SIGN, was duplicated from ICAM-1 in mammalian evolution, but was lost in the rodent genome. FEBS Lett. 579:2901-2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao, P. S., B. Wang, R. Buitrago, J. Y. Shyy, and J. P. Cooke. 1997. Nitric oxide regulates monocyte chemotactic protein-1. Circulation 96:934-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, G., R. Iyer, S. Bittker, D. Cooper, J. Small, G. P. Wormser, and I. Schwartz. 2004. Variations in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly culture medium modulate infectivity and pathogenicity of Borrelia burgdorferi clinical isolates. Infect. Immun. 72:6702-6706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weis, J. J. 2002. Host-pathogen interactions and the pathogenesis of murine Lyme disease. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 14:399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson, R. W., C. M. Ballantyne, C. W. Smith, C. Montgomery, A. Bradley, W. E. O'Brien, and A. L. Beaudet. 1993. Gene targeting yields a CD18-mutant mouse for study of inflammation. J. Immunol. 151:1571-1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoshimura, T., N. Yuhki, S. K. Moore, E. Appella, M. I. Lerman, and E. J. Leonard. 1989. Human monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1). Full-length cDNA cloning, expression in mitogen-stimulated blood mononuclear leukocytes, and sequence similarity to mouse competence gene JE. FEBS Lett. 244:487-493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]