Abstract

An American Type Culture Collection reference strain and eight clinical strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, all of which were susceptible to isoniazid (INH) (mean MIC, 0.06 mg/liter) and negative for the Ser315Thr katG mutation, were left in their BACTEC 12B vials (for use with the BACTEC 460-TB method) containing 0.1 mg of INH per liter for periods of up to 28 days after the completion of the antibiotic susceptibility test. Each eventually grew to levels compatible with those of INH-resistant strains. Successive passages in INH-containing BACTEC 12B vials and onto solid media showed that the resistance noted above was maintained. Successive passages of these M. tuberculosis strains in which INH resistance had been induced into BACTEC 12B vials or solid media containing stepwise increases in INH concentrations eventually yielded organisms resistant to 20 mg of INH per liter. Transfer of cells in which INH resistance had been induced to drug-free medium followed by repeated passages in that medium eventually yielded organisms whose susceptibility to INH was identical to that of the original parent strains. The cycle of induced INH resistance could be repeated with these now INH-susceptible cells. The use of M. tuberculosis identification probes and IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses of cultures throughout the induction of INH resistance and the reversal of resistance in drug-free medium eliminated the possibility that the culture was contaminated or that the initial specimen had a mixed type of infection. Induced high-level resistance to INH (20 mg/liter) could be reduced 100-fold with a subinhibitory concentration of reserpine but not with verapamil. These results collectively suggest that high-level resistance to INH can be induced in INH-susceptible M. tuberculosis strains by the induction of a reserpine-sensitive efflux mechanism.

Isoniazid (INH) is highly effective against Mycobacterium tuberculosis (3), having MICs that range from 0.02 to 0.06 mg/liter (28). However, the rates of resistance to INH have been escalating worldwide (27). The mechanism by which the resistance of M. tuberculosis to INH takes place is very complex and has been ascribed to the individual mutation of genes encoding a catalase-peroxidase (katG) (30, 32), an enzyme of the mycolic acid pathway (inhA) (1), and a β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthetase (kasA) (12). Because only about 50 to 60% of all strains studied so far have mutations in any of these genes associated with resistance to INH (18, 29), conventional wisdom dictates that other genetic factors bestowing resistance to INH must be involved. To this extent, resistance to INH has also been related to its neutralization by the overproduction of arylamine N-acetyltransferase (15), by limitations of NAD+-binding proteins (4, 10), and by the overexpression of antioxidant enzymes that compensate for the loss of function of the KatG protein (7). The first and last mechanisms still fail to account for the resistance in at least 20% of all INH-resistant strains (29). Plasmids play no role in acquired INH resistance in M. tuberculosis (29).

Resistance to INH is not totally accounted for by the mechanisms described above, since recent evidence shows that resistance to INH in Mycobacterium smegmatis can also be mediated by an energy-dependent efflux pump (5). Efflux pumps that render an organism resistant to one or more antibiotics have been identified in all bacteria that have been subjected to such analyses, including mycobacteria (16, 22). These pumps are normally present in the plasma membrane of the bacterium and afford protection from toxic substances that are recognized as substrates by the pump. Susceptibility to a given antibiotic that is a coincidental substrate for a pump may be considered the result of overcoming the effectiveness of the pump due to its limited number of units. Because among the isolates of one strain there are members that have different quantitative susceptibilities to a given antibiotic attributed to genotypic variation (20), it is possible that these differences may be due to a variation in the number of existing efflux pumps. Furthermore, these variations may be due to a mechanism that controls the number of such pump units. The demonstration of antibiotic efflux pumps in mycobacteria has raised the obvious question of whether these or any antibiotic efflux pump is subject to an increase in their number, which in turn renders the organism increasingly resistant to the antibiotic. To this extent we have attempted and succeeded to induce INH sensitivity in M. tuberculosis strains increasingly resistant to INH by mechanisms that do not involve the selection of mutations that bestow resistance to this antibiotic. The mechanism by which this induced resistance to INH takes place might involve an efflux pump.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibiotics and chemicals.

INH, chlorpromazine (CPZ), verapamil, and reserpine were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Quimica SA, Madrid, Spain. Rifampin, streptomycin, and ethambutol as well as all materials and equipment used to test the antibiotic susceptibilities of the M. tuberculosis strains tested with the BACTEC 460-TB system were purchased from Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems, Sparks, Md., and were prepared according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. Solid and liquid media used for purposes other than susceptibility testing are identified in the legends to the figures or in the tables and were purchased from Difco, Detroit, Mich. All solutions were freshly prepared on the day of any given experiment.

Microorganisms.

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (strain ATCC 27294 from the American Type Culture Collection ([ATCC]) and eight clinical isolates of M. tuberculosis, the latter of which were isolated from untreated patients and previously shown to be susceptible to INH, rifampin, streptomycin, and ethambutol by the BACTEC 460-TB system (S. Siddiqi, BACTEC TB system, product and procedure manual, 1980, Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems, Towson, Md.), were selected for this study and were designated INH-susceptible strains.

Drug susceptibility assays by the BACTEC 460-TB radiometric proportion method and determination of INH MICs by the broth (BACTEC) radiometric method and the agar dilution method.

The indirect drug susceptibility assay (the BACTEC 460-TB radiometric proportion method) was conducted with the respective desired final concentrations of INH (0.1 mg/liter), rifampin (2 mg/liter), streptomycin (6 mg/liter), and ethambutol (7.5 mg/liter) by the procedure and with the interpretive criteria recommended by the manufacturer (21; S. Siddiqi, BACTEC TB system, product and procedure manual, Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems) and by Rastogi et al. (19). Absolute control vials (with no drug) and drug-containing vials were inoculated with approximately 105 to 106 CFU of an organism identified as M. tuberculosis by rRNA-DNA probe hybridization (AccuProbe; Gen-Probe-BioMerieux, Lyon, France) (9). A separate 1/100 dilution of each bacterial suspension served as the proportional control. All vials were incubated at 37°C and were evaluated daily until the growth index of the proportional control reached 30, which was within 4 to 12 days.

The MIC of INH was determined for the H37Rv (ATCC 27294) control strain and clinical strains by the modified broth radiometric method of Lee and Heifets (11; S. Siddiqi, BACTEC TB system, product and procedure manual, Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems). The MIC was defined as the lowest INH concentration that completely inhibited the generation of 14CO2 after an incubation period of 12 days.

The determination of the INH MIC by the agar dilution method was performed as described previously (6, 8).

The simultaneous use of Middlebrook 7H11 solid medium for susceptibility testing and MIC determination was necessary because the agar dilution method, the “gold standard” in mycobacteriology (6, 8), affords accurate determination of the percentage of resistant bacteria in the population present in the broth used by the radiometric method as well as for the isolation of single colonies. Both methods yielded comparable MICs.

Inducement of INH resistance, reversal of resistance, and repetition of the cycle of INH-induced resistance.

The vials that were used to determine the susceptibilities of the clinical and INH-susceptible (ATCC 27294) strains to INH (0.1 mg/liter) and that would normally be discarded after a maximum of 12 days (S. Siddiqi, BACTEC TB system, product and procedure manual, Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems) were retained in the incubator for an additional period of time. By the end of 28 days, all of the vials yielded visible and radiometric evidence of growth. The contents of these vials were identified as M. tuberculosis by conventional biochemical methods (6) and rRNA-DNA probe hybridization and were evaluated for INH susceptibility by the BACTEC 460-TB and solid medium methods. IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (IS6110-RFLP analysis) (17, 25) confirmed that each of the bacterial populations that could now grow in the presence of 0.1 mg of INH per liter was identical to the initial parent population. The MIC of INH for each of these strains was determined and compared to that of the initial respective parent, and aliquots of 0.1 ml from growing cultures containing a concentration of INH just below the MIC were inoculated into fresh BACTEC 12B vials containing the lowest INH concentration that had completely inhibited the growth of the previous population. At the end of 10 to 28 days these vials showed evidence of maximum growth, and a new INH susceptibility test and MIC determination confirmed their capacity to grow in the presence of higher concentrations of INH that had previously been shown to inhibit growth. This sequential process was conducted for five additional consecutive passages, with each passage containing a stepwise increase in the concentration of INH corresponding to the lowest concentration that had inhibited growth in the previous passage. This process was conducted in parallel with solid medium. The latter method provided colonies that could be assayed for identity and antibiotic susceptibility and colonies that could be assayed by other procedures to ensure that what was being observed with liquid medium was also taking place in solid medium.

This phase of the study consumed an average of 230 days (see Fig. 2) with the radiometric broth medium and yielded M. tuberculosis isolates that were capable of growing in medium containing a concentration of INH as high as 20 mg/liter.

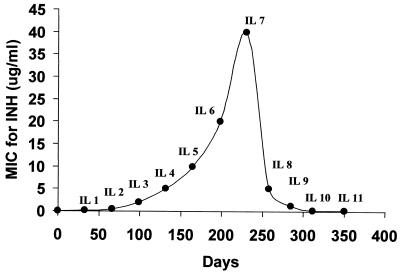

FIG. 2.

Time course of induced INH resistance and reversion of the H37Rv (ATCC 27294) reference strain. Culture of INH-susceptible isolates (time zero; MIC, 0.03 mg/liter) in INH-containing medium (0.1 mg/liter) incubated beyond the antibiotic susceptibility assay time frame (4 to 12 days) resulted in evident growth after 28 days. The ability to grow in 0.1 mg of INH per liter was confirmed, the MICs were determined, and the cells were designated as having induced INH resistance (MIC, 0.2 mg/liter) at IL1. These cells were then exposed to INH at concentrations that corresponded to the MIC for the previous passage phase, and after 21 days the growing cells were then tested as described above and the cells were designated as having induced INH resistance (MIC, 0.5 mg/liter) at IL2. The process was continued to IL7, at which time the cells were able to grow in the presence of 20 mg of INH per liter (MIC, 40 mg/liter). Cells at IL7 were repeatedly transferred to drug-free medium. The MICs were determined between passages, and the MICs gradually decreased (IL8, IL9, and IL10), reaching the MIC for the initial parent strain (0.06 mg/liter) at IL11. The cells present in the culture at IL11 served as a source for the repeat cycle of induced resistance to INH (data not shown).

The potency of the INH in the medium was assayed throughout the period described above after the removal of mycobacteria by filtration (filter pore size, 0.22 μm; Millipore), and the cell-free medium was reinoculated with the control strain, H37Rv (ATCC 27294).

After the sixth passage (when the strains were growing in INH at 20 mg/liter), each derived INH-resistant M. tuberculosis isolate obtained from the initially INH-susceptible strains was subsequently transferred to INH-free medium and incubated for an extended period of 28 days. An aliquot from each vial was then transferred to fresh INH-free medium, and these vials were reincubated for the same extended period; three more consecutive passages in drug-free medium were conducted for each derived strain. The INH MIC for each strain was determined after each passage in drug-free medium. After the fourth passage the susceptibility testing criteria for INH susceptibility were verified by procedures conducted with broth and solid media.

Aliquots from the last passage in drug-free medium were subjected to the same antibiotic susceptibility assay described above for the respective initial strains; i.e., they were allowed to remain in the incubator well past their period of antibiotic susceptibility until evidence of growth. The contents were subjected to the same procedures used for the eventual inducement of high-level resistance to INH described above.

IS6110-RFLP analysis and analysis of katG mutations by PCR-RFLP analysis.

Before and after the inducement of resistance to INH, strain H37Rv (ATCC 27294) and the clinical strains were subjected to IS6110-RFLP analysis (17, 25) to determine possible contamination or to detect an initial mixed culture, as described previously (20).

Determination of the most common point mutation in katG, consistently found at position 315 (serine to threonine [S315→T]) in clinical isolates with high-level INH resistance, was conducted with the initial ATCC control strain, representatives of the initial INH-susceptible clinical strains, representatives of the progeny in which INH resistance had been induced and obtained after the sixth consecutive passage in INH, and representatives obtained from the last (fourth) consecutive passage in the absence of INH, as described previously (24, 26). Two mutants previously found to have katG mutations were similarly analyzed and served as positive controls.

MICs of putative inhibitors of efflux pumps for the strains of M. tuberculosis used in this study and effects of the inhibitors on induced INH resistance.

The MICs of CPZ, verapamil, and reserpine for strain ATTC 27294 and the clinical strains of M. tuberculosis were determined with the BACTEC 460-TB system described above, except that INH was replaced by separate various concentrations of known inhibitors of efflux pumps: CPZ at 1.25 to 40 mg/liter, verapamil at 8 to 5,000 mg/liter, and reserpine at 0.01 to 160 mg/liter.

These inhibitors of efflux pumps were separately added to cultures at concentrations that were previously shown to have no effect on the growth of the initial ATCC and clinical strains of M. tuberculosis used in this study. The concentrations of these compounds used in combination with INH, as well as the concentration of INH, in cultures containing representatives of the initially INH-susceptible strains, representatives from cultures induced to have high levels of resistance to INH, or representatives from cultures whose progeny had reverted in drug-free medium to their initial susceptibility to INH are described in the figure legends and in the tables, where appropriate.

RESULTS

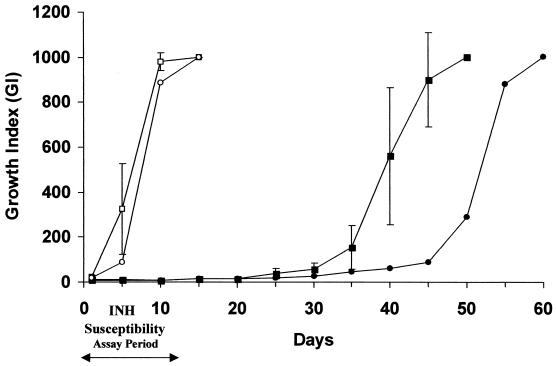

Repetition of the antibiotic susceptibility assay with M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATTC 27294) and the eight clinical strains with the BACTEC 460-TB system indicated that each of these acid-fast-positive strains was susceptible to 0.1 mg of INH per liter as well as to rifampin, streptomycin, and ethambutol. Extending the incubation period for INH-susceptible cultures in INH-containing medium beyond the completion of the antibiotic susceptibility assay yielded evidence of visible growth. By the end of 28 days after the beginning of the INH susceptibility assay, the growth in all of the cultures with initially susceptible isolates reached a level comparable to that for the individual controls grown in drug-free medium (Fig. 1). Direct examination of the contents of each vial by the use of identification probes and staining for acid-fast bacilli indicated that all of the organisms were M. tuberculosis. However, unlike their parents, which were all positive by staining with the Ziehl-Neelsen acid-fast stain, the cells from any given INH-containing vial presented with wide variations in acid-fast staining, ranging from negative to positive staining status (Table 1). This variation in acid-fast staining is probably due to some inhibition of cell wall mycolic acid synthesis (23). Given that INH resistance is associated with the loss of catalase activity (13), the contents of the INH-containing vials were tested for this biochemical characteristic. All retained catalase activity (Table 1). The possibility that the potency of INH in the vials had been affected by prolonged incubation was ruled out since the medium, when filtered free of cells, was as effective as freshly made INH-containing medium against M. tuberculosis isolates with proven INH susceptibility (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Appearance of INH resistance after completion of INH susceptibility assay. The growth curves of the H37Rv (ATCC 27294) reference strain (•) and the eight clinical INH-susceptible strains (▪) in BACTEC 12B vials containing 0.1 mg of INH per liter and the H37Rv (ATCC 27294) reference strain (○) and the eight clinical INH-susceptible strains (□) grown in drug-free medium as controls are shown. The results for the eight clinical strains are recorded at 5-day intervals, with each point being the mean ± standard deviation of the daily readings. All strains were initially susceptible to 0.1 mg of INH per liter, as evidenced by the results at the end of the INH susceptibility assay period (maximum, 12 days). Incubation for a maximum of an additional 28 days yielded a growth index that was indicative of resistance to INH.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of contents of INH-containing BACTEC 12B vialsa

| Examination | Procedure | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Acid-fast staining | Ziehl-Neelsen staining | Quality of acid-fast stain diminished; the mycobacteria had a blue color on staining with methylene blue |

| Nonmycobacterial contamination | Culture on agar-blood medium | Negative |

| Culture on Lowenstein-Jensen medium | Positive | |

| M. tuberculosis identification | Accuprobe rRNA-DNA probes | Positive |

| Conventional biochemical tests | Positive | |

| Catalase activity | Conventional biochemical test | Positive |

| INH potency of the medium | BACTEC 12B vials with medium filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter; new test with M. tuberculosis H37Rv n(ATCC 27294) susceptible to INH | No growth of the reference strain |

| Average MIC of INH for the parental strains initially INH susceptible | Radiometric method with Middlebrook 7H12 broth and agar dilution method | 0.06 mg/liter |

| Susceptibility of the strains with INH-induced resistance to INH | BACTEC 460-TB radiometric proportion method for susceptibility to INH at 0.1 mg/liter | All strains were resistant at IL1 |

| Agar dilution method with Middlebrook 7H11 solid medium for susceptibility to INH at 0.2 mg/liter | All strains were resistant at IL1 | |

| Average INH MIC for strains at IL1 with INH-induced resistance | Radiometric method with Middlebrook 7H12 broth | 0.2 mg/liter |

The vials contained ATCC H37Rv reference strain (ATCC 27294) and clinical strains initially susceptible to 0.1 mg of INH per liter and, when incubated for an additional 28 days, yielded a growth index that corresponded to that of organisms resistant to that concentration of INH

Inducement of INH resistance.

Once the possibility of contamination and the possibility that the INH-containing medium had reduced potency were ruled out, aliquots of each of the cultures that were then growing in the presence of INH were subjected to a repeat INH susceptibility assay with the BACTEC 460-TB system and solid medium. Separate determinations of the MIC of INH by the modified broth radiometric method yielded similar data (data not shown). For a better understanding of the INH MICs, the values presented in the text and tables refer only to the INH concentrations used with the modified broth radiometric method of Lee and Heifets (11; S. Siddiqi, BACTEC TB system, product and procedure manual, Becton Dickinson Diagnostic Instrument Systems). The results presented in Table 1 show that at the first stage of resistance to INH by initially INH-susceptible strains (induction level 1 [IL1]) these organisms were indeed resistant to INH (0.1 mg/liter) and grew on INH-containing agar (0.2 mg/liter). The MICs of INH for these strains were much higher than those for the parents used at the beginning of this study (Table 1).

Aliquots of these cultures with INH-induced resistance at IL1 were transferred to fresh BACTEC 12B vials containing a concentration of INH that corresponded to the new MIC (0.2 mg/liter). These cultures reached full growth by the end of 10 to 21 days and were subjected to INH MIC determination, after which time they served as sources for the next passage in medium containing a concentration of INH that corresponded to that which was shown to be the new INH MIC for the strains in the previous passage. These organisms, referred to as isolates with INH-induced resistance at the second induction level (IL2), were assayed for determination of the INH MIC (the INH MIC at IL2 was then 0.5 mg/liter) and were used as sources for five additional serial passages, with each succeeding passage containing a concentration of INH that corresponded to the previous MIC for the strain with INH-induced resistance at IL2, IL3, IL4, IL5, IL6, and IL7. These passages were also conducted with solid medium containing equivalent concentrations of INH, and the plates were evaluated for the numbers of CFU. Figure 2 describes the increases in the INH MICs for each of the induction levels when the ATCC strain was subjected to stepwise increases in the concentrations of INH, as described above. This procedure yielded M. tuberculosis isolates that were capable of growing in liquid or solid medium containing 20.0 mg of INH per liter. All eight clinical strains were subjected to the same procedures used for the induction of high-level resistance to INH, and similar results were obtained, with little difference in the amount of time required for the manifestation of induced resistance at each sequential level of induced resistance being detected (data not shown due to limitation of space).

Reversal of INH resistance.

Although the contents of each culture at the conclusion of each passage phase were shown by the use of identification probes to be M. tuberculosis (Table 1), there was the real possibility that the increasing level of resistance to INH was due to the selection of mutants containing any one of the known mutations associated with resistance to INH. Since mutations remain true when the isolates are transferred to drug-free medium, aliquots were taken from cultures of isolates that were growing in 20.0 mg of INH per liter (induced resistance to INH at IL7) and transferred to drug-free medium, after which time serial passages were conducted in drug-free medium. Between serial passages, an assay for determination of the INH MIC was conducted. As shown in Fig. 2, the MICs for isolates from each successive passage (IL8, IL9, and IL10) continued to decrease, eventually reaching that for the initial parent strain (average MIC at IL11, 0.06 mg/liter). The latter progeny that by this time were fully INH susceptible were subjected to prolonged incubation in INH, as were their original parents, and the cycle of induced resistance to INH was again successfully repeated (Fig. 2).

The induction of INH resistance and its reversibility with repeated passage in drug-free medium, followed by the repeat of the INH resistance induction cycle, argue against the involvement of any chromosomal mutation that may have been selected or the introduction of a contaminant during the manipulations described above. Nevertheless, to eliminate these two possibilities, the probability of which are low, representative strains from each phase of the cycle (susceptible strains and strains with induced resistance) were subjected to IS6110-RFLP analysis and katG mutation identification analysis. The IS6110-RFLP pattern remained identical for each representative throughout the cycle, thus eliminating any chance that the appearance of an increased level of resistance was due to the introduction of a contaminant or to the testing of a specimen of a mixed type (data not shown). The appearance of INH resistance is not due to the selection of katG mutants, which are known to be the most prevalently associated with high-level resistance to INH as a result of the S315→T mutation, since all of the PCR-RFLP analyses that detect this point mutation were negative for all strains tested (data not shown) (23, 26).

Reduction of levels of INH resistance by an efflux pump inhibitor.

The induction of high-level resistance to INH may be due to the activation or induction of an efflux pump mechanism(s). For this purpose INH-susceptible reference strain M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) and isolates with INH-induced resistance at IL7 (resistant to INH at 20.0 mg/liter [MIC, 40 mg/liter]) were evaluated for the presence of an efflux pump by the use of known inhibitors of bacterial efflux pumps such as CPZ (14), verapamil, and reserpine (5, 16, 22). The existence of an efflux pump that renders a bacterium resistant to a given antibiotic is shown by the ability of known inhibitors of efflux pumps to reduce the level of resistance to the antibiotic. The concentration selected for an inhibitor of an efflux pump must be one that has a nominal effect on the growth of the bacterium itself so that the effects related to the action of the pump on the activity of a given antibiotic can be isolated. Table 2 identifies the highest concentrations of CPZ, verapamil, and reserpine that had no effect on the initial INH-susceptible ATCC 27294 reference strain and the clinical strains used in this study, as well as the concentrations that correspond to their MICs. Whereas subinhibitory concentrations of CPZ or verapamil did not affect the ability of the cells with induced INH resistance at IL7 to grow in the presence of 20 mg of INH per liter (data not shown), reserpine at 20 mg/liter reduced the ability of all of the strains at IL7 to grow in the presence of 20.0 to 0.2 mg of INH liter (Table 3). Complete inhibition of the growth of strains with induced INH resistance at IL7 in the presence of 0.1 mg of INH per liter required an average reserpine concentration of 40 mg/liter. However, although this concentration of reserpine alone had no effect on the growth of the initial INH-susceptible strains (Table 2), it did inhibit the growth of these cells with induced INH resistance by as much as 15% (Table 3), an effect which we deemed the nominal effect. The data presented in Table 3 also show that when strains with induced resistance to INH at 20 mg/liter (IL7) were grown in the presence of reserpine at 20 mg/liter and INH at 0.1 and 0.2 mg/liter (with the 0.1-mg/liter concentration being the critical concentration of INH used as the cutoff for the demonstration of resistance of a clinical specimen), their growth was not completely inhibited. This apparent resistance may reflect the large number of efflux pump units that have been induced, with the inhibitory capability of INH overcome by this concentration of reserpine. This interpretation receives support from the data also presented in Table 3, which demonstrate that an increase in the concentration of reserpine to 40 mg/liter practically eliminates resistance to INH. It may be noted from the data in Table 3 that strains that reverted to INH susceptibility had some demonstrable resistance to concentrations of INH that were slightly above and at the cutoff point used for the interpretation of resistance to INH. We interpret these results to indicate that even after extensive culture in drug-free medium, there is still evidence of a reserpine-sensitive mechanism which is completely inhibited only by the higher concentration of reserpine (40 mg/liter).

TABLE 2.

Highest concentrations of CPZ, verapamil, and reserpine with nominal effects on growth of M. tuberculosis parental strains (INH susceptible) and the MICs for complete inhibition of growtha

| Drug |

M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294)

|

M. tuberculosis clinical strains

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concn (mg/liter) for NE | MIC (mg/liter) | Concn (mg/liter) for NE | MIC (mg/liter) | |

| CPZ | 5 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| Verapamil | 51.2 | 128 | 51.2 | 128 |

| Reserpine | 40 | 100 | 40 | 80 |

The values are averages of two reproducible determinations for strain H37Rv (ATCC 27294) and the means for eight clinical strains. The concentration that achieves a nominal effect (NE) is defined as the highest concentration of the drug that produced less than 15% inhibition of growth.

TABLE 3.

Effect of a known inhibitor of efflux pumps, reserpine, on activities of INH on INH-susceptible strains, strains at IL7 with induced INH resistance,a and INH-susceptible revertants at IL11a

| Drug (concn [mg/liter]) | % of maximum growth

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INH-S M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) | INH-S M. tuberculosis clinical strains | INH-IR (IL7) M. tuberculosis H37Rv (ATCC 27294) | INH-IR (IL7) M. tuberculosis clinical strains | INH-Srev (IL11) M. tuberculosis H37RV (ATCC 27294) | INH-Srev (IL11) M. tuberculosis clinical strains | |

| INH (20) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| INH (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| INH (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Reserpine (20) | 92 | 95 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 95 |

| Reserpine (40) | 85 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 92 |

| INH (20) + reserpine (20) | 0 | 0 | 7 | 12 | 0 | 0 |

| INH (0.2) + reserpine (20) | 0 | 0 | 40 | 42 | 10 | 8 |

| INH (0.1) + reserpine (20) | 0 | 0 | 52 | 60 | 22 | 31 |

| INH (20) + reserpine (40) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| INH (0.2) + reserpine (40) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| INH (0.1) + reserpine (40) | 0 | 0 | 10 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

The strains grew in the presence of 20 mg of INH per liter.

Percentage of maximum growth was calculated as the quotient between the number of CFU in the drug(s)-containing BACTEC 12B vial and that in the absolute control vial without any drug 1 day before the latter achieves a maximum growth index of 999. INH-S, INH-susceptible; INH-IR, INH-induced resistant; INH-Srev, INH-susceptible revertant.

DISCUSSION

Considerable variation in antibiotic susceptibility is found among the different species of mycobacteria, such that whereas M. tuberculosis is highly susceptible to INH, M. smegmatis and other fast-growing mycobacteria are resistant to the drug (8, 31). The susceptibility of M. tuberculosis to INH is due to an efficient conversion of the drug INH by the catalase-peroxidase enzyme to a compound that inhibits mycolic acid synthesis (31). Recently, natural resistance of M. smegmatis to INH has also been ascribed to a verapamil- and reserpine-sensitive efflux pump (5). The observations made from our study indicate for the first time that INH-susceptible strains of M. tuberculosis exposed to INH for a prolonged period of time can become resistant to 0.1 mg of INH per liter. This induced resistance to INH is reproducible and can gradually be increased to 20 mg/liter by gradual stepwise increases in the concentration of INH. Induced resistance can be effectively reversed by consecutive passage in drug-free medium. The cycle of induced resistance to INH can be repeated by these procedures, probably ad infinitum. The use of identification probes and IS6110-RFLP analysis ruled out any possibility that a contaminant was present or that the initial specimen was of a mixed type. The reversal of induced resistance to INH by simple serial passage in drug-free medium ruled out the possibility of selection of INH resistance mutations that could account for the INH resistance. Direct evaluation of the cultures at each phase of the study for the presence of katG mutations further supported the contention that the induction of resistance to INH was not due to the selection of mutations most commonly associated with resistance to INH. Lastly, although gene amplification can cause increased levels of antibiotic resistance in other species of bacteria by overproduction of an antibiotic-inactivating enzyme (2), it is unlikely that the high-level resistance to INH induced in this study is caused by a similar mechanism, inasmuch as the resistance observed in our study continues while the organism is replicating in the presence of high levels of INH. The loss of this resistance requires a large number of replications afforded by five prolonged passages in drug-free medium, whereas antibiotic resistance due to gene amplification is much more rapidly lost. In addition, gene amplification has not been observed with M. tuberculosis due to the high degree of inherent stability of the chromosome (29, 31).

As mentioned in the introduction, the INH resistance in only about 70 to 80% of M. tuberculosis strains has been correlated to mutations in any of the genes assigned as potential targets or to alternative metabolic pathways for INH inhibition (18, 29). Efflux pumps that render bacteria resistant to antibiotics have been identified in all bacteria, including mycobacteria, studied to date (5, 16, 22). The correlation of antibiotic resistance to an efflux pump is made when the level of antibiotic resistance is reduced in the presence of both antibiotic and an inhibitor of the pump itself. Without exception, each of the studies cited evaluated the organisms for the presence of a preexisting efflux pump (5, 16, 22). Accordingly, strains of M. tuberculosis that are susceptible to INH would by definition not contain a mutation for INH resistance, nor would they be expected to harbor an efflux pump capable of pumping out INH. The demonstration in our study that high-level resistance to INH can be gradually induced in INH-susceptible strains of M. tuberculosis via a mechanism that does not involve a mutation but that is sensitive to reserpine supports the contention that induced resistance might be due to an efflux pump mechanism. Whether induced resistance is due to activation of a preexisting efflux pump, an increase in the number of efflux pump units, or de novo synthesis of the pump itself was not determined in the present study. The growth inhibition results (Table 3) obtained by the use of the lower concentration of reserpine (20 mg/liter) in combination with 0.2 or 0.1 mg of INH per liter with strains obtained at IL11 (INH-susceptible revertant strains), although consistent with the presence of an efflux pump mechanism, are difficult to interpret, inasmuch as the growth of these strains should be fully inhibited. Although it is possible that the induced resistance to INH in our study was due to the selection of mutants capable of synthesizing an efflux pump, we consider this possibility remote, inasmuch as the ATCC control strain and all eight clinical strains were induced to present the efflux pump.

The induction of high-level resistance to INH by continuous exposure to increasing concentrations of the antibiotic has not been described previously. The induction of INH resistance by INH may occur during INH therapy and may account for the remainder of the INH resistance that is not accounted for by mutations and that, due to the limitation of the time interval used for the INH susceptibility assay, is not detected.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Molnar and Cost Action B16 (“Reversal of antibiotic resistance by the inhibition of efflux pumps”) of the European Commission for advice and recommendations during the course of this study.

We are also indebted to the Institute of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene of Lisbon and its Scientific Council and Units of STD and Virology for encouragement and support and the Tygerberg Hospital, Harry Crossley Foundation, and IAEA (projects SAF6/003 and CRP 9925) for financial assistance (to T. C. Victor).

REFERENCES

- 1.Banerjee, A., E. Dubnau, A. Quemard, V. Balasubramanian, K. S. Um, T. Wilson, D. Collins, G. De Lisle, and W. R. Jacobs, Jr. 1994. inhA, a gene encoding a target for isoniazid and ethionamide in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science 263:227-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergstrom, S., and S. Normark. 1979. Beta-lactam resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli caused by elevated production of the ampC-mediated chromosomal beta-lactamase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 16:427-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein, J., W. A. Lott, B. A. Steinberg, and H. L. Yale. 1952. Chemotherapy of experimental tuberculosis. V. Isonicotinic acid hydrazide (Nydrazid) and related compounds. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 76:568-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen, P., and W. R. Bishai. 1998. Novel selection for isoniazid (INH) resistance genes supports a role for NAD+-binding proteins in mycobacterial INH resistance. Infect. Immun. 66:5099-5106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choudhuri, B. S., S. Sen, and P. Chakrabarti. 1999. Isoniazid accumulation in Mycobacterium smegmatis is modulated by proton motive force-driven and ATP-dependent extrusion systems. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 256:682-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David, H., V. Levy-Frébault, and M. F. Thorel. 1989. Méthodes de laboratoire pour mycobactériologie clinique. Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

- 7.Hillas, P. J., F. S. del Alba, J. Oyarzabal, A. Wilks, and P. R. Ortiz De Montellano. 2000. The AhpC and AhpD antioxidant defense system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Biol. Chem. 275:18801-18809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kent, P. A., and G. P. Kubica. 1985. Public health mycobacteriology—a guide for the level III laboratory. Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga.

- 9.Lebrun, L., F. Espinasse, J. D. Poveda, and V. Vincent-Levy-Frebault. 1992. Evaluation of nonradioactive DNA probes for identification of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2476-2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, A. S., A. S. Teo, and S. Y. Wong. 2001. Novel mutations in ndh in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2157-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, C. N., and L. B. Heifets. 1987. Determination of minimal inhibitory concentrations of antituberculosis drugs by radiometric and conventional methods. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 136:349-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mdluli, K., R. A. Slayden, Y. Zhu, S. Ramaswamy, X. Pan, D. Mead, D. D. Crane, J. M. Musser, and C. E. Barry III. 1998. Inhibition of a Mycobacterium tuberculosis beta-ketoacyl ACP synthase by isoniazid. Science 280:1607-1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middlebrook, G. 1954. Isoniazid-resistance and catalase activity of tubercle bacilli. Am. Rev. Tuberc. 69:471-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molnar, J., A. Hever, I. Fakla, J. Fischer, I. Ocsovski, and A. Aszalos. 1997. Inhibition of the transport function of membrane proteins by some substituted phenothiazines in E. coli and multidrug resistant tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 17:481-486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payton, M., R. Auty, R. Delgoda, M. Everett, and E. Sim. 1999. Cloning and characterization of arylamine N-acetyltransferase genes from Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis: increased expression results in isoniazid resistance. J. Bacteriol. 181:1343-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piddock, L. J., K. J. Williams, and V. Ricci. 2000. Accumulation of rifampicin by Mycobacterium aurum, Mycobacterium smegmatis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45:159-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portugal, I., L. Brum, M. Viveiros, J. Moniz Pereira, and H. David. 1999. Outbreak of multiple-drug-resistant tuberculosis in Lisbon: detection by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 3:207-213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramaswamy, S., and J. M. Musser. 1998. Molecular genetic basis of antimicrobial agent resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: 1998 update. Tuber. Lung. Dis. 79:3-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rastogi, N., V. Labrousse, and K. S. Goh. 1996. In vitro activities of fourteen antimicrobial agents against drug susceptible and resistant clinical isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and comparative intracellular activities against the virulent H37Rv strain in human macrophages. Curr. Microbiol. 33:167-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rinder, H., K. T. Mieskes, and T. Loscher. 2001. Heteroresistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 5:339-345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siddiqi, S. H., J. E. Hawkins, and A. Laszlo. 1985. Interlaboratory drug susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a radiometric procedure and two conventional methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 22:919-923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva, P. E., F. Bigi, M. de la Paz Santangelo, M. I. Romano, C. Martin, A. Cataldi, and J. A. Ainsa. 2001. Characterization of P55, a multidrug efflux pump in Mycobacterium bovis and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:800-804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takayama, K., L. Wang, and H. L. David. 1972. Effect of isoniazid on the in vitro mycolic acid synthesis, cell growth and viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2:29-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uhl, J. R., G. S. Sandhu, B. C. Kline, and F. R. Cockerill III. 1996. PCR-RFLP detection of point mutations in catalase-peroxidase gene (katG) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with isoniazid resistance, p. 144-155. In D. H. Persing (ed.), PCR protocols for emerging infectious diseases. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 25.van Embden, J. D., M. D. Cave, J. T. Crawford, J. W. Dale, K. D. Eisenach, B. Gicquel, P. Hermans, C. Martin, R. McAdam, and T. M. Shinnick. 1993. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:406-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victor, T. C., A. M. Jordaan, A. van Rie, G. D. van der Spuy, M. Richardson, P. D. van Helden, and R. Warren. 1999. Detection of mutations in drug resistance genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a dot-blot hybridization strategy. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:343-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. 2000. Anti-tuberculosis drug resistance in the world. Report 2. Prevalence and trends. The WHO/IUATLD Global Project on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 28.Youatt, J. 1969. A review of the action of isoniazid. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 99:729-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang, Y., and A. Telenti. 2000. Genetics of drug resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, p. 111-130. In G. F. Hatfull and W. R. Jacobs (ed.), Molecular genetics of mycobacteria. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 30.Zhang, Y., B. Heym, B. Allen, D. Young, and S. Cole. 1992. The catalase-peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nature 358:591-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, Y., S. Dhandayuthapani, and V. Deretic. 1996. Molecular basis for the exquisite sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to isoniazid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13212-13216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang, Y., T. Garbe, and D. Young. 1993. Transformation with katG restores isoniazid-sensitivity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates resistant to a range of drug concentrations. Mol. Microbiol. 8:521-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]