Abstract

Combination therapy could be of benefit for the treatment of invasive yeast infections. However, in vitro interaction studies are relatively scarce and the interpretation of the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index can be contradictory due to various definitions used; not all information on the interaction study is used in the index, and different MIC end points exist for different classes of drugs. Fitting an interaction model to the whole response surface and estimation of an interaction coefficient alpha (ICα) would overcome these objections and has the additional advantage that confidence intervals of the interaction are obtained. The efficacy of flucytosine (5FC) in combination with amphotericin B (AB) and fluconazole (FCZ) was studied against 35 yeast isolates in triplicate (Candida albicans [n = 9], Candida glabrata [n = 9], Candida krusei [n = 9], and Cryptococcus neoformans [n = 8]) using a broth microdilution checkerboard method and measuring growth after 48 h by a spectrophotometer. The FIC index and ICα were determined, the latter by estimation from the response surface approach described by Greco et al. (W. R. Greco, G. Bravo, and J. C. Parsons, Pharmacol. Rev. 47:331-385, 1995) by using a computer program developed for that purpose. For the 5FC-FCZ combination, the interactions determined by the ICα generally were in concordance with the interactions determined by the FIC index, but large discrepancies were found between both methods for the 5FC-AB combination. These could mainly be explained by shortcomings in the FIC approach. The in vitro interaction of 5FC-AB demonstrated variable results depending on the tested Candida isolate. In general, the 5FC-FCZ combination was antagonistic against Candida species, but for some Candida isolates synergism was found. For C. neoformans the interaction for both combinations was highly dependent on the tested isolate and the method used. Response surface approach is an alternative method for determining the interaction between antifungal agents. By using this approach, some of the problems encountered with the FIC were overcome.

Opportunistic yeast infections, such as candidiasis and cryptococcosis, occur particularly in immunocompromised patients, such as cancer patients (2) and transplant recipients (9, 15). The treatment of these infections is still problematic. Only a few antifungal agents are currently available, and although therapeutic options have increased considerably during the last decade due to the introduction of new agents (7), efficacy is not always optimal. Several drugs cause toxicity, and resistance to new agents is on the rise (7).

One way to enhance treatment is to combine antifungal agents. Antifungal agents given in combination may improve efficacy due to synergism, and because the dose can possibly be lowered, side effects could be reduced. Another advantage of combination therapy is the reduction of the development of resistance and possibly a shorter duration of therapy (13, 16).

Flucytosine (5FC) is a drug with a limited spectrum of action that includes Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans (19). Because resistance to 5FC emerges relatively fast, the drug is preferably given in combination with other antifungal agents. Although 5FC has been given in combination with other agents and has been evaluated in several clinical trials, little is known of the in vitro interaction of 5FC with other drugs (6, 13, 17).

The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index is the most frequently used analysis to quantify drug interaction (5). Despite the fact that this method has some important disadvantages, it is widely used. The first disadvantage is that one index (the FIC index) is used for many results: the result of every well in the checkerboard is confined in one index, while there may be more refinement necessary since at some concentrations there may be synergism but for others there may be indifference or even antagonism. Another disadvantage is that for some antifungal combinations it is not clear at which MIC end point the combination should be read and, thus, how to determine the FIC index. For amphotericin B (AB) and most antibacterial agents, end points are easily defined (one dilution) and the MIC is read as the lowest drug concentration that showed 100% growth inhibition (MIC-0) (11). For 5FC and especially for azoles, end points are less sharp (range of twofold dilutions) and exhibit a trailing growth effect. The MIC is read as the lowest drug concentration that showed 50% or more growth inhibition (MIC-2) (11). When AB is combined with 5FC or an azole, the combination can be read at either MIC-0 or at MIC-2. Finally, a third disadvantage is that there are several different definitions described in the literature for the interpretation of the FIC index (1, 5, 13, 20, 21), and it is still not clear which of these definitions should be used.

To overcome these problems alternative methods have been sought for and developed, especially in the area of antiviral drugs (3, 14). Instead of the reading of a single well (the MIC), the whole response surface is taken into account. By fitting a model to the whole response surface, an objective criterion for the interaction is obtained. The interaction can be further characterized by statistical analysis and confidence intervals. One of the models based on the response surface approach is the fully parametric model described by Greco et al. (8) which is an Emax-based model (Emax model or Hill equation with variable slope) and fits to the entire data set with a nonlinear regression analysis. The nature and the intensity of an interaction are summarized with a nonunit, concentration-independent interaction parameter that includes the uncertainty in the estimate. We developed a program, called ModLab, which fits the Greco model to the whole response surface and then estimates the model parameters, including the interaction parameter, with their 95% confidence intervals.

The aim of this study was to investigate the in vitro interaction of 5FC in combination with AB or fluconazole (FCZ) against a collection of 35 clinical yeast isolates by a broth microdilution checkerboard assay. The interaction was determined using both the FIC index and a response surface approach.

(Part of these results were presented at the 40th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Canada, 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Test isolates.

Thirty-five clinical yeast isolates were tested: Candida albicans (n = 9), Candida glabrata (n = 9), Candida krusei (n = 9), and Cryptococcus neoformans (n = 8). The isolates were part of the private collection of the Department of Medical Microbiology, University Medical Center Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands. The isolates were grown on Sabouraud glucose agar at 28°C for 24 to 72 h. They were subcultured again on Sabouraud glucose agar for 24 h before preparation of the inoculum. All isolates were tested in triplicate on different days.

Candida parapsilosis (ATCC 22019) and C. neoformans (ATCC 90112) were used for quality control in all experiments.

Antifungal agents.

5FC (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands), AB (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Woerden, The Netherlands), and FCZ (Pfizer, Capelle aan den IJssel, The Netherlands) were obtained as powders. 5FC and FCZ were dissolved in distilled water and AB was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide to make stock solutions. The stock solutions were held at −80°C until use.

Serial twofold dilutions of each antifungal agent were prepared following NCCLS guidelines (12). Final dilutions were made in RPMI 1640 medium (with l-glutamine, without bicarbonate) (GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies, Woerden, The Netherlands) buffered to pH 7.0 with morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) (0.165 mol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany).

Interaction of drugs in vitro.

Drug interactions were assessed by a broth microdilution checkerboard method. The final concentrations of the antifungal agents ranged from 0.004 to 512 μg/ml for 5FC, 0.002 to 2 μg/ml for AB, and 0.008 to 512 μg/ml for FCZ. Aliquots of 50 μl of each drug at a concentration four times the targeted final concentration were dispensed in the wells of flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plates (Costar, Corning, N.Y.).

Yeast inocula were prepared spectrophotometrically (12), and further diluted in RPMI 1640 medium. In order to obtain a final concentration of 0.5 to 2.5 × 103 CFU/ml, 100 μl of the yeast suspension was added to each well. The microtiter plates were incubated at 35°C for 48 h.

Readings were performed spectrophotometrically with a microplate reader (Anthos htIII; Anthos Labtec Instruments, Salzburg, Austria) at 405 nm. The optical densities (ODs) of the blank, which consisted of an uninoculated plate incubated together with the inoculated plates, were subtracted from the ODs of the inoculated plates. The percentage of growth for each well was calculated by comparing the OD of the wells with that of the drug-free control: (OD405 of wells that contained the drug/OD405 of the drug-free well) × 100%.

The MIC of AB was defined as the lowest concentration that inhibited growth by 100% compared with that of the drug-free well (MIC-0). The MICs of 5FC and FCZ were defined as the lowest concentrations that inhibited growth by 80% or more compared with that of the drug-free well (MIC-1). For the 5FC-AB combination MIC-0 was taken as an end point, and for the 5FC-FCZ combination MIC-1 was taken as an end point.

Definitions.

Drug interaction was determined by the FIC index (5) and by the interaction coefficient alpha (ICα) based on the response surface approach by Greco et al. (8).

The FIC index was defined as follows:

|

(1) |

|

The interaction was defined as synergistic if the FIC index was <1, additive if the FIC index was equal to 1, and antagonistic if the FIC index was >1 (1).

The response surface approach by Greco et al. was described by the following equation (7):

|

(2) |

where

|

(3) |

and where D1 and D2 are the concentrations of drugs 1 and 2, IC50,1 and IC50,2 are the concentrations of drug 1 and drug 2 resulting in 50% inhibition, E is the measured response, Econ is the control response, m1 and m2 are the slope parameters for drug 1 and 2 in a constant ratio, and α is the synergism-antagonism interaction parameter (ICα).

This model was fitted directly to the entire set of experimental data (percentages of growth for all concentrations of the two drugs alone or in combination) with a nonweighted, nonlinear regression analysis using a computer program (ModLab; Medimatics, Maastricht, The Netherlands). The program estimated the model parameters, and it also calculated the 95% confidence interval for each parameter. Validation of obtained parameters was done using the program Syner, kindly provided to us by G. L. Drusano.

If the estimate of α is zero, the combination is additive. If it is positive, the interaction is synergistic. If it is negative, the interaction is antagonistic. The estimate of α has an associated 95% confidence interval. If the confidence interval does not overlap zero, this provides the statistical significance for the estimate of the interaction. That is, if the 95% confidence interval crosses zero, the interaction is additive. If it does not and α is positive, the interaction is significantly synergistic. If it does not and α is negative, the interaction is significantly antagonistic (3, 8).

Agreement between the FIC index and the response surface approach.

The interactions found by the FIC index were compared with those found by the response surface approach for both the 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ combinations. The percentage agreement between both methods for both combinations was determined.

RESULTS

All yeast isolates grew well after 48 h of incubation at 35°C. In each batch of broth microdilution tests, the MICs for the quality control strains were within the reference ranges.

MIC data.

Table 1 shows the MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ for the 35 yeast isolates, using the MIC-0 for AB and the MIC-1 for 5FC and FCZ.

TABLE 1.

MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ for 35 yeast isolates

| Species and isolate | MIC (μg/ml) of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 5FCa | ABb | FCZa | |

| C. albicansc | |||

| 1_25 | 0.125 | 0.125 | 32 |

| 1_59 | 0.5 | 0.062 | 64 |

| 1_66 | 0.125 | 0.062 | 8 |

| 1_77 | 4 | 0.125 | 32 |

| 574 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 2 |

| 1201 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 2274 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 16 |

| 2308 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 8 |

| 4518 | 0.125 | 0.5 | 2 |

| C. kruseid | |||

| 1_27 | 4 | 0.25 | 16 |

| 1_31 | 16 | 0.25 | 16 |

| 1_32 | 2 | 0.125 | 16 |

| 1_34 | 8 | 0.25 | 16 |

| 1_35 | 2 | 0.031 | 16 |

| 2_12 | 8 | 0.25 | 16 |

| 2_34 | 8 | 0.25 | 32 |

| D30 | 8 | 0.062 | 32 |

| D95 | 8 | 0.125 | 0.25 |

| C. glabratae | |||

| 1_28 | 0.031 | 0.062 | 16 |

| 1_68 | 0.062 | 0.125 | 64 |

| 1_70 | 4 | 0.25 | 16 |

| 1_79 | 0.062 | 0.125 | 256 |

| 2_50 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 64 |

| 2_57 | 0.062 | 0.062 | 8 |

| 499 | 0.125 | 1 | 2 |

| 608 | 0.062 | 0.5 | 8 |

| 1143 | 0.062 | 0.5 | 8 |

| C. neoformansf | |||

| 125 | 4 | 0.5 | 1 |

| 451 | 1 | 0.062 | 2 |

| 467 | 8 | 0.25 | 4 |

| 661 | 2 | 0.031 | 1 |

| 3849 | 4 | 0.125 | 2 |

| 3904 | 2 | 0.125 | 4 |

| 7621 | 2 | 0.062 | 2 |

| 9019 | 128 | 0.062 | 2 |

MIC-1 was taken as an endpoint.

MIC-0 was taken as an endpoint.

For C. albicans, the MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited were 0.125, 0.25, and 8 μg/ml, respectively.

For C. krusei, the MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited were 8, 0.25, and 16 μg/ml, respectively.

For C. glabrata, the MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited were 0.062, 0.125, and 16 μg/ml, respectively.

For C. neoformans, the MICs of 5FC, AB, and FCZ at which 50% of the isolates tested were inhibited were 3, 0.095, and 2 μg/ml, respectively.

FIC index.

Table 2 shows the FIC indices of the 35 yeast isolates for the 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ combinations determined by a broth microdilution checkerboard method, together with the results obtained by the response surface approach (see below).

TABLE 2.

In vitro interaction between 5FC and AB or FCZ for 35 yeast isolates as determined by FIC index and ICαa

| Species and isolate | Mean result (range) for 5FC interaction with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AB

|

FCZ

|

|||

| FIC | ICα | FIC | ICα | |

| C. albicans | ||||

| 1_25 | 2.12 (2.12) | 0.870 (−0.021 to 1.437) | 2.34 (0.25 to 4.25) | −0.114 (−0.133 to 0.074) |

| 1_59 | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.75) | −0.125 (−0.297 to 0.027) | 2.17 (2.01 to 2.25) | 0.144 (−0.377 to 1.107) |

| 1_66 | 0.65 (0.56 to 0.75) | 0.015 (−0.097 to 0.216) | 9.50 (2.50 to 16.50) | −0.167 (−0.373 to −0.042) |

| 1_77 | 1.53 (0.56 to 2.02) | 0.892 (0.539 to 1.301) | 1.17 (0.51 to 1.50) | −0.187 (−0.220 to −0.144) |

| 574 | 1.33 (1.00 to 1.50) | −0.071 (−0.086 to 0.059) | 0.09 (0.05 to 0.13) | 22.475 (1.193 to 61.607) |

| 1201 | 1.34 (1.00 to 2.03) | −0.078 (−0.113 to −0.055) | 0.09 (0.07 to 0.12) | 16.656 (16.656) |

| 2274 | 1.46 (0.62 to 2.25) | −0.107 (−0.127 to −0.084) | 0.29 (0.06 to 0.53) | 6.140 (0.535 to 11.746) |

| 2308 | 0.66 (0.56 to 0.75) | 0.145 (−0.081 to −0.584) | 0.08 (0.07 to 0.08) | 24.952 (8.299 to 37.077) |

| 4518 | 0.78 (0.56 to 1.00) | −0.136 (−0.158 to −0.114) | 0.07 (0.07 to 0.08) | 30.212 (−0.138 to 84.525) |

| C. krusei | ||||

| 1_27 | 2.31 (2.13 to 2.50) | 0.255 (−0.143 to 0.966) | 2.88 (2.12 to 4.25) | −0.288 (−0.497 to −0.179) |

| 1_31 | 1.17 (0.50 to 2.25) | 0.996 (−0.214 to 2.461) | 1.58 (1.00 to 2.25) | −0.232 (−0.268 to −0.196) |

| 1_32 | 0.75 (0.63 to 1.00) | 0.145 (−0.205 to 0.677) | 2.17 (1.50 to 2.50) | −0.173 (−0.212 to −0.127) |

| 1_34 | 1.46 (0.63 to 2.25) | −0.286 (−0.335 to −0.254) | 2.42 (2.25 to 2.50) | −0.635 (−0.991 to −0.353) |

| 1_35 | 0.50 (0.50) | 0.455 (−0.430 to 1.486) | 2.25 (2.25) | −0.312 (−0.462 to −0.206) |

| 2_12 | 0.58 (0.53 to 0.63) | 0.523 (0.523) | 2.25 (2.00 to 2.50) | −0.280 (−0.358 to −0.165) |

| 2_34 | 2.14 (2.03 to 2.25) | 0.195 (0.111 to 0.345) | 1.50 (0.50 to 2.50) | −0.241 (−0.368 to −0.166) |

| D30 | 1.14 (0.63 to 2.03) | 0.287 (−0.209 to 1.083) | 2.00 (1.00 to 2.50) | −0.223 (−0.405 to −0.089) |

| D95 | 1.83 (1.00 to 2.25) | −0.182 (−0.230 to −0.136) | 0.31 (0.31) | 0.527 (0.149 to 0.893) |

| C. glabrata | ||||

| 1_28 | 1.67 (0.77 to 2.13) | 0.283 (−0.436 to 1.002) | 4.42 (4.25 to 4.50) | −0.262 (−0.301 to 0.218) |

| 1_68 | 0.57 (0.38 to 0.75) | 0.705 (−0.180 to 2.385) | 5.04 (2.13 to 8.50) | −0.503 (−0.667 to −0.274) |

| 1_70 | 1.60 (0.75 to 2.03) | 1.239 (0.090 to 2.097) | 1.69 (1.50 to 2.06) | −0.179 (−0.202 to −0.162) |

| 1_79 | 0.96 (0.63 to 1.50) | −0.138 (−0.191 to −0.086) | 1.50 (1.50) | −0.643 (−0.685 to −0.582) |

| 2_50 | 0.92 (0.63 to 1.50) | −0.077 (−0.101 to −0.028) | 4.42 (4.25 to 4.50) | −0.285 (−0.317 to −0.256) |

| 2_57 | 0.91 (0.62 to 1.50) | −0.036 (−0.064 to −0.006) | 16.50 (16.50) | −0.180 (−0.213 to −0.164) |

| 499 | 1.89 (0.75 to 2.58) | −0.120 (−0.145 to −0.096) | 7.08 (4.50 to 8.50) | −0.036 (−0.036) |

| 608 | 0.61 (0.57 to 0.63) | −0.164 (−0.210 to −0.110) | 8.42 (8.25 to 8.50) | −0.132 (−0.152 to −0.108) |

| 1143 | 0.79 (0.63 to 1.00) | −0.129 (−0.153 to −0.101) | 16.50 (16.50) | −0.200 (−0.323 to −0.114) |

| C. neoformans | ||||

| 125 | 1.29 (0.75 to 2.12) | −0.143 (−0.163 to −0.124) | 9.02 (2.06 to 16.50) | −0.264 (−0.567 to −0.065) |

| 451 | 1.58 (1.00 to 2.24) | 0.039 (−0.063 to 0.230) | 1.13 (0.63 to 2.13) | 0.214 (0.214) |

| 467 | 2.38 (2.25 to 2.50) | −0.074 (−0.104 to −0.044) | 0.63 (0.63) | 13.241 (0.507 to 25.975) |

| 661 | 1.05 (0.50 to 2.12) | 0.641 (0.385 to 0.950) | 1.83 (1.50 to 2.50) | 0.142 (0.124) |

| 3849 | 2.08 (1.50 to 2.50) | 0.358 (0.385) | 2.42 (2.25 to 2.50) | −0.024 (−0.024) |

| 3904 | 2.63 (1.00 to 4.25) | 0.106 (−0.049 to 0.297) | 2.00 (1.50 to 2.50) | −0.042 (−0.053 to −0.031) |

| 7621 | 1.42 (0.63 to 2.12) | 0.218 (−0.088 to 0.796) | 1.44 (0.56 to 2.25) | −0.024 (−0.031 to −0.019) |

| 9019 | 3.50 (2.50 to 4.50) | 0.896 (0.896) | 1.63 (1.00 to 2.25) | −0.105 (−0.119 to −0.091) |

Results based on triplicate experiments.

5FC-AB combination.

For the 5FC-AB combination much variation was found between the Candida isolates, both between species as well as within species. Synergism was observed for four C. albicans isolates, and antagonism was observed for five C. albicans isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.65 to 2.12 and a median FIC (FIC50) of 1.33. For C. krusei synergism was observed for three isolates, and antagonism was observed for six isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.50 to 2.31 and a FIC50 of 1.17. For C. glabrata synergism was observed for six isolates and antagonism was observed for three isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.57 to 1.89 and a FIC50 of 0.92. Thus, the FIC50 for all 27 Candida isolates indicate that, overall, there was slight in vitro antagonism for the 5FC-AB combination (FIC50 = 1.14), but this combination appeared to be synergistic for some isolates. In vitro antagonism was observed for all eight C. neoformans isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 1.05 to 3.50 and a FIC50 of 1.83.

5FC-FCZ combination.

For the 5FC-FCZ combination, synergism was observed for five C. albicans isolates and antagonism for four C. albicans isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.07 to 9.50 and a FIC50 of 0.29. For C. krusei synergism was observed for one isolate and antagonism was observed for eight isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.31 to 2.88 and a FIC50 of 2.17. For C. glabrata antagonism was observed for all nine isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 1.50 to 16.50 and a FIC50 of 5.04. Importantly, for all C. glabrata isolates the mean MIC of the triplicates of FCZ increased from 64 to >128 μg/ml when used in combination with 5FC. In general, the 5FC-FCZ combination was antagonistic against Candida species (FIC50 = 2.17), although marked synergism was observed for some isolates (FIC index down to 0.07). Interestingly, the MIC of 5FC was lowered by at least 1 dilution step when combined with FCZ for all Candida isolates.

Synergism was observed for one C. neoformans isolate, and antagonism was observed for seven C. neoformans isolates, with the FIC index ranging from 0.63 to 9.02 and a FIC50 of 1.73.

Response surface approach.

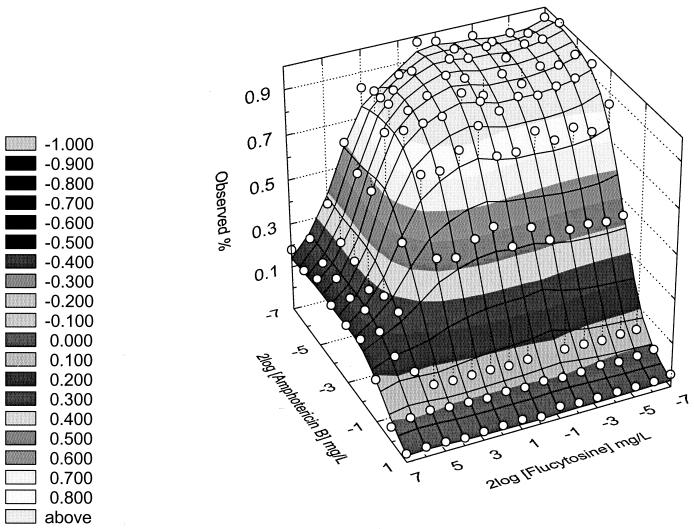

Table 2 also shows the interaction coefficient (ICα) of the 35 yeast isolates for 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ as determined by the response surface approach (8). Model fits were performed for each isolate and drug combination. An example is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Effect surface response of one of the triplicates of Candida krusei 1_25 for 5FC in combination with AB. The ICα (95% confidence interval) of this isolate was 1.196 (0.853 to 1.676), indicating synergism.

5FC-AB combination.

For the 5FC-AB combination much variation was found between the yeast isolates. Synergism was observed for four C. albicans isolates, and antagonism for five C. albicans isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.136 to 0.892 and a median ICα (ICα50) of −0.071. For C. krusei synergism was observed for seven isolates and antagonism was observed for two isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.286 to 0.996 and an ICα50 of 0.255. For C. glabrata synergism was observed for three isolates and antagonism was observed for six isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.164 to 1.239 and an ICα50 of −0.077. The ICα50 for all 27 Candida isolates indicated slight synergism for the 5FC-AB combination (ICα50 = 0.015).

Synergism was observed for six C. neoformans isolates, and antagonism was observed for two C. neoformans isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.143 to 0.896 and an ICα50 of 0.162.

5FC-FCZ combination.

For the 5FC-FCZ combination synergism was observed for six of the C. albicans isolates and antagonism was observed for three of the C. albicans isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.187 to 30.212 and an ICα50 of 6.140. For C. krusei synergism was observed for one isolate and antagonism was observed for eight isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.635 to 0.527 and an ICα50 of −0.241. For C. glabrata antagonism was observed for all nine isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.643 to −0.036 and an ICα50 of −0.200. In general, the 5FC-FCZ combination was antagonistic against Candida species (ICα50 = −0.180) but highly synergistic in some isolates (ICα up to 30.212).

Synergism was observed for three C. neoformans isolates, and antagonism was observed for five C. neoformans isolates, with the ICα ranging from −0.264 to 13.241 and an ICα50 of −0.024.

Agreement between the FIC index and the response surface approach.

The percentage of agreement in the interpretation of the FIC index results and the response surface approach results was 91% for the 5FC-FCZ combination. For the 5FC-AB combination the agreement between both methods was much lower, namely, 40%: only 14 of the 35 yeast isolates gave the same results when determined by both methods. Thus, there is a discrepancy between the results of the two methods.

The effect of several variables on the level of agreement.

Because we found a low level of agreement between both methods for the 5FC-AB combination, we analyzed the effect of several variables on the level of agreement.

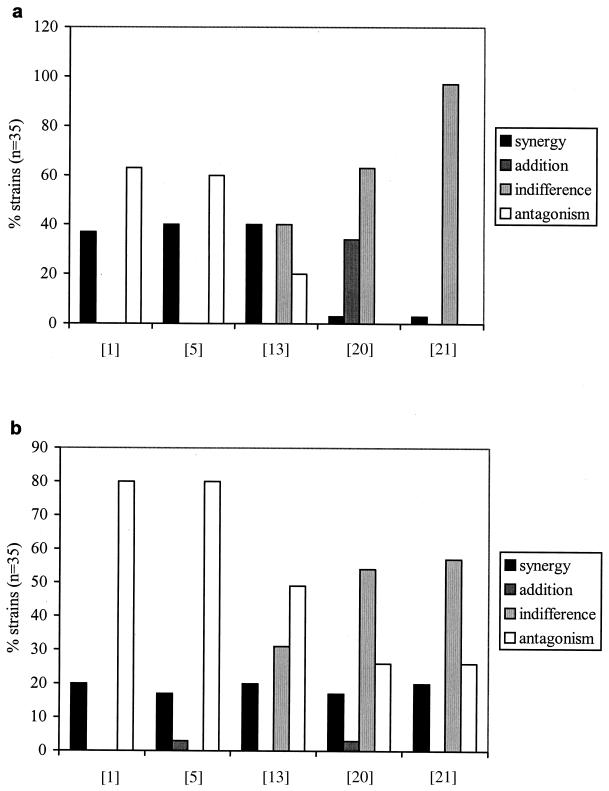

Interpretation of FIC index.

Different definitions for the interpretation of the FIC index can be found in the literature (Table 3). Figure 2 shows the percentages of synergism, addition, indifference, and antagonism for 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ, determined by the different definitions for the interpretation of the FIC index given in Table 3. As can be observed from the figures, large discrepancies occur. For instance, for the 5FC-FCZ combination synergism was found between 17 and 20% of isolates, while antagonism was found between 26% (following the definition of Walsh et al. [20] or White et al. [21]) to 80% (following the definition of Berenbaum [1] or Eliopoulos [5]) of isolates.

TABLE 3.

Definitions for interpretation of the FIC index

| Interpretation | Definition according to reference:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 13 | 20 | 21 | |

| Synergism | <1 | ≤0.5 | <1 | ≤0.5 | ≤0.5 |

| Additive | =1 | 0.5-1 | 1 | 0.5-1 | |

| Indifferent | 1-2 | >1-4 | >0.5-4 | ||

| Antagonism | >1 | >1 | >2 | >4 | >4 |

FIG. 2.

Interactions found by using different definitions for the FIC index for the 5FC-AB (a) and for the 5FC-FCZ (b) combinations.

Table 4 shows the percentage of agreement between the interpretation of the FIC index results and the response surface approach for both the 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ combination depending on the definition chosen. As can be observed, the level of agreement varied between 0 and 40% for the 5FC-AB combination and between 43% and 91% for the 5FC-FCZ combination.

TABLE 4.

Level of agreement between the interpretation of the FIC index results and the response surface approach resultsa

| Reference | % Agreement between FIC and response surface approach results

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 5FC-AB | 5FC-FCZ | |

| 1 | 40 | 91 |

| 5 | 20 | 89 |

| 13 | 29 | 71 |

| 20 | 0 | 43 |

| 21 | 0 | 43 |

Level of agreement depending on the chosen definition for the interpretation of the FIC index for both the 5FC-AB and 5FC-FCZ combination.

Dependence of FIC on MIC end point.

The level of agreement between the interpretation of the FIC index results and the response surface approach results for the 5FC-AB combination was determined with regard to the MIC and the degree of inhibition used in the combination. The level of agreement varied between 43% (15 of 35 isolates) (MIC-0 for AB, MIC-1 for 5FC, and 100% inhibition for the combination) and 60% (21 of 35 isolates) (MIC-0 for AB and 5FC and 100% inhibition for the combination; MIC-0 for AB, MIC-1 for 5FC and 80% inhibition for the combination; and MIC-1 for AB and 5FC and 80% inhibition for the combination).

DISCUSSION

In the present study we determined the interaction between 5FC and AB or FCZ and showed that the interaction is largely dependent on the tested isolate. We also demonstrate that the use of the FIC index in synergy studies of antifungal agents has some important disadvantages in that the results can be interpreted in different ways. First of all there are different definitions described in the literature for the interpretation of the FIC index (Table 3). There is no consensus on which definition to use in synergy studies. In this study we compared the interactions found by these different definitions for both the combination of 5FC with AB and that of 5FC with FCZ. Large discrepancies were found, depending on the definitions used. For example, synergism was found between 17 and 20% of isolates, while antagonism varied from 26 to 80% of the isolates for the combination of 5FC with FCZ. Not only the definitions but also the lack of a statistical criterion to define these interactions contribute to these varying results.

A second disadvantage is that it is not clear at which MIC end point the combination should be read. This question is particularly important when a combination of drugs with different MIC end points is used. In another study we determined the interaction between AB and itraconazole against 15 Aspergillus fumigatus isolates (18). Depending on the chosen MIC end point the mean FIC index varied between 1.016 and 2.077 for 10 itraconazole-susceptible isolates or between 0.308 and 1.767 for five itraconazole-resistant isolates.

Thus, the interaction found by the FIC index depends not only on the chosen combination but also on the choice of interpretation of the FIC index and, for some drug combinations, on the choice of MIC end point. From this, we conclude that the FIC index is not an optimal instrument to describe interactions between antifungal agents.

To overcome these problems a response surface approach as described by Greco et al. (8) can be used to determine the interaction between antifungal agents. The use of a model fit at least allows an objective statistical criterion and it makes an arbitrarily chosen end point unnecessary. Fitting of a model to the whole data surface not only allows the optimal use of information in the data but also allows the determination of error estimates of the interaction coefficient, thereby indicating whether the interaction is significant or not. Since the effect of drug interaction may vary between individual isolates this is an important feature. For the FIC index a statistical approach was described earlier by Drusano, but because of its complexity it is generally not used (4). Alternatively, not only does the interaction coefficient indicate whether there is significance or not, but the value found also gives an indication of the degree of interaction. This approach was used successfully in synergy studies of antivirals (3, 14).

In fitting the surface response model to the data, two approaches can be taken. The first one, and in most cases the approach of preference, would be to use an inverse variance weighting scheme. In such a circumstance, one would take the three determinations for each strain and calculate the mean and standard deviation of the response for each well. The mean would be the observation. The variance would be calculated from the standard deviation, and the inverse of the observation variance would be taken as the weight. We used this approach initially, but we encountered the problem that the intra-assay variance was much smaller than the interassay variance. Thus, although the surface fit would be very reasonable for each of the three experiments, using the inverse variance for each measurement in each well did not always work out. We therefore chose to fit the surface to the results of the individual experiments. Although this assumes homoscedasticity, the results of the model fit suggest this to be fairly reasonable.

To determine the relationship between the two methods, the level of agreement was determined for the various combinations. For the combination of 5FC with FCZ the level of agreement between the interpretation of the FIC index results and the response surface approach results was very high (91%).

In contrast, the level of agreement for the combination of 5FC with AB was very low (40%). There may be two explanations for the low level of agreement of this latter combination, namely, the chosen definition for the interpretation of the FIC index (Table 4) and, moreover, the chosen MIC end point (data in Results). This is substantiated by the fact that for the combination of 5FC with FCZ the level of agreement was relatively high. MICs of both 5FC and FCZ are read at the same end point; thus, there is no difficulty in the choice of the end point when calculating the FIC index. In contrast, for the combination of 5FC with AB there is a difference in the reading end points (MIC). The results show that the choice of end point much more influences the level of agreement (data in Results) than the definition itself (Table 4). The use of the response surface approach precludes all these interpretation problems, by estimating parameters independent of a chosen end point.

The clinically most used combination of antifungal drugs is 5FC with AB for Candida and Cryptococcus infections. The superiority of the combination over either drug alone in Cryptococcus infections has been described in both case series and randomized trials (19). Currently no randomized trials have been conducted to determine whether combination therapy of 5FC with AB is superior to monotherapy for invasive Candida infections. However, combination therapy is recommended in several conditions of invasive candidiasis, such as meningitis, endophthalmitis, endocarditis and peritonitis (19). Furthermore, it has been shown that human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with cryptococcal meningitis could possibly benefit from the combination of 5FC with FCZ (10). However, these studies provide no data on the interactions of the two combinations in vitro. The combination of 5FC with AB showed synergism or indifference against C. neoformans and Candida strains (6, 17). The combination of 5FC with FCZ showed synergism, indifference or addition, but no antagonism against C. neoformans strains (13).

In this study we found that the in vitro interaction of the combination of 5FC with AB demonstrated variable results depending on the tested Candida isolate. The combination of 5FC with FCZ was generally antagonistic, but for some Candida isolates synergism was found. The in vitro inhibitory activity of 5FC was greatly enhanced by the addition of FCZ. The MICs of 5FC for Candida were decreased by at least 1 dilution step. On the other hand, the addition of 5FC did not greatly enhance the in vitro activity of FCZ. For the C. glabrata strains the mean MIC of the triplicates of FCZ even increased from 64 μg/ml when used alone to >128 μg/ml when combined with 5FC.

The interaction found for the in vitro combination of 5FC with AB or FCZ against C. neoformans varied, depending on both the tested isolate and the used method (FIC index or response surface approach).

A next step would be to determine whether differences in clinical outcome (responders versus nonresponders of therapy) could be explained using this approach of interaction studies.

Our results do not concur completely with previous in vitro findings (6, 13). This may mainly be due to the fact that different methods (broth macro- and microdilution), different MIC end points and different methods of interpretation of the results were used and possibly also that different fungal strains were tested. In the light of these differences, it is necessary to develop a standard methodology to determine in vitro antifungal interactions. The response surface approach would be a good alternative.

It has to be emphasized that the results obtained in in vitro studies do not necessarily correlate with clinical outcome. Although we found antagonism between 5FC and FCZ for several strains, this combination has been found to be very useful in treating people with cryptococcal meningitis. Also AB in combination with 5FC is thought to be useful in the treatment of various forms of candidiasis. Other factors such as prolonged therapy and pharmacokinetic properties of the drugs play an important role in in vivo efficacy.

We conclude that the response surface approach is a good alternative for determining the interaction between drugs against yeasts and has considerable advantages over conventional methods.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berenbaum, M. C. 1978. A method for testing for synergy with any number of agents. J. Infect. Dis. 137:122-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodey, G., B. Bueltmann, W. Duguid, D. Gibbs, H. Hanak, M. Hotchi, et al. 1992. Fungal infections in cancer patients: an international autopsy. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 11:99-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drusano, G. L., D. Z. D'Argenio, W. Symonds, P. A. Bilello, J. McDowell, B. Sadler, et al. 1998. Nucleoside analog 1592U89 and human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor 141W94 are synergistic in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2153-2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drusano, G. L. 1988. Role of pharmacokinetics in the outcome of infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:289-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliopoulos, G. M., and R. C. Moellering, Jr. 1991. Antimicrobial combinations, p. 432-492. In U. Lorian (ed.), Antibiotics in laboratory medicine, 3rd ed. Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 6.Ghannoum, M. A., Y. Fue, A. S. Ibrahim, L. A. Mortara, M. C. Shafiq, J. E. Edwards, J. R., et al. 1995. In vitro determination of optimal antifungal combinations against Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:2459-2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghannoum, M. A., and L. B. Rice. 1999. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 12:501-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greco, W. R., G. Bravo, and J. C. Parsons. 1995. The search for synergy: A critical review from a response surface perspective. Pharmacol. Rev. 47:331-385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hibberd, P. L., and R. H. Rubin. 1994. Clinical aspects of fungal infection in organ transplant recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:S33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen, R. A., S. A. Bozzette, B. E. Jones, D. Haghighat, M. A. Leal, D. Forthal, et al. 1994. Fluconazole combined with flucytosine for treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis. 19:741-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1998. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of conidium-forming filamentous fungi: proposed standard M38-P. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 12.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 1997. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts: approved standard M27-A. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 13.Nguyen, M. H., F. Barchiesi, V. L. Yu, and M. G. Rinaldi. 1995. In vitro evaluation of combination of fluconazole and flucytosine against Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1691-1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick, A. K., T. J. Boritzki, and L. A. Bloom. 1997. Activities of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitor nelfinavir mesylate in combination with reverse transcriptase and protease inhibitors against acute HIV-1 infection in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2159-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paya, C. V. 1993. Fungal infections in solid-organ transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 16:677-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polak, A. 1988. Combination therapy with antifungal drugs. Mycoses 32:45-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polak, A. 1999. The past, present and future of antimycotic combination therapy. Mycoses 42:355-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Te Dorsthorst, D. T. A., P. E. Verweij, J. F. G. M. Meis, N. C. Punt, and J. W. Mouton. 2002. Comparison of fractional inhibitory concentration index with response surface modeling for characterization of in vitro interaction of antifungals against itraconazole-susceptible and -resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:702-707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vermes, A., H.-J. Guchelaar, and J. Dankert. 2000. Flucytosine: a review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 46:171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walsh, T. J., J. Peter, D. A. McGough, A. W. Fothergill, M. G. Rinaldi, and P. A. Pizzo. 1995. Activities of amphotericin B and antifungal azoles alone and in combination against Pseudallescheria boydii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1361-1364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White, R. L., D. S. Burgess, M. Manduru, and J. A. Bosso. 1996. Comparison of three different in vitro methods of detecting synergy: time-kill, checkerboard, and E test. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1914-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]