Abstract

The quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of topoisomerase II and IV genes from Stenotrophomonas maltophilia ATCC 13637 were sequenced and compared with the corresponding regions of 32 unrelated S. maltophilia clinical strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 0.1 to 64 μg/ml. GyrA (Leu-55 to Gln-155, Escherichia coli numbering), GyrB (Met-391 to Phe-513), ParC (Ile-34 to Arg-124), and ParE (Leu-396 to Leu-567) fragments from strain ATCC 13637 showed high degrees of identity to the corresponding regions from the phytopathogen Xylella fastidiosa, with the degrees of identity ranging from 85.0 to 93.5%. Lower degrees of identity to the corresponding regions from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (70.9 to 88.6%) and E. coli (73.0 to 88.6%) were observed. Amino acid changes were present in GyrA fragments from 9 of the 32 strains at positions 70, 85, 90, 103, 112, 113, 119, and 124; but there was no consistent relation to higher ciprofloxacin MICs. The absence of changes at positions 83 and 87, commonly involved in quinolone resistance in gram-negative bacteria, was unexpected. The GyrB sequences were identical in all strains, and only one strain (ciprofloxacin MIC, 16 μg/ml) showed a ParC amino acid change (Ser-80→Arg). In contrast, a high frequency (16 of 32 strains) of amino acid replacements was present in ParE. The frequencies of alterations at positions 437, 465, 477, and 485 were higher (P < 0.05) in strains from cystic fibrosis patients, but these changes were not linked with high ciprofloxacin MICs. An efflux phenotype, screened by the detection of decreases of at least twofold doubling dilutions of the ciprofloxacin MIC in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (0.5 μg/ml) or reserpine (10 μg/ml), was suspected in seven strains. These results suggest that topoisomerases II and IV may not be the primary targets involved in quinolone resistance in S. maltophilia.

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is increasingly detected as a nosocomial pathogen, especially in immunocompromised patients, those subjected to invasive procedures, and those who are receiving broad-spectrum antimicrobials (8). It has also been rising to prominence in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients (33). This organism is inherently resistant to a variety of antimicrobials, including most β-lactams and aminoglycosides (8, 32). Due to the unusual antimicrobial susceptibility profile, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is regarded as the therapy of choice for the treatment of serious infections caused by this organism. However, studies of the in vitro activities of fluoroquinolones against S. maltophilia have reported a relative low rate of resistance (32). Theoretically, at concentrations achievable in serum or lung tissue, fluoroquinolones may inhibit nearly all S. maltophilia isolates (31) and may play a role in the treatment of infections caused by this pathogen. Consequently, the emergence of quinolone-resistant strains could have negative clinical implications.

Quinolone resistance mechanisms have been described and characterized in a wide variety of organisms (16). They have mostly been related to specific mutations that lead to aminoacid alterations in the quinolone-resistance determining regions (QRDRs) within the subunits constituting topoisomerases II (GyrA and GyrB) and IV (ParC and ParE), which are involved in DNA replication, recombination, and transcription and in the partitioning of the replicated chromosome (16, 37). In addition, efflux-based mechanisms and permeability defects can also affect quinolone susceptibility (16). Quinolone resistance in S. maltophilia has mostly been correlated with a low level of permeability (23) and with efflux-based mechanisms (1, 42). Although the possibility that mutations exist in the topoisomerase genes of S. maltophilia has been suggested (11), no studies have confirmed the role of these targets in quinolone resistance. The aim of the study described here was to characterize the QRDRs of GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE in a reference quinolone-susceptible strain (S. maltophilia ATCC 13637) and also to investigate possible changes in the amino acid sequences of topoisomerases (II and IV) in 32 unrelated S. maltophilia clinical strains expressing different levels of quinolone susceptibility. Moreover, evidence of an efflux mechanism was sought by determining fluoroquinolone MICs in the presence of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) and reserpine.

(This work was presented in part at the 40th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2000 [S. Valdezate et al., Abstr. 40th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 1036, 2000].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

Thirty-two S. maltophilia clinical strains with different ciprofloxacin susceptibilities (MIC range, 0.1 to 64 μg/ml) collected from 1991 to 1998 at Ramón y Cajal Hospital, a 1,200-bed tertiary-care teaching hospital, were included in the study. Sixteen strains were isolated from 15 CF patients; and 16 strains were collected from respiratory (n = 6), blood (n = 5), and other clinical sources (n = 5) from 16 non-CF hospitalized patients. Moreover, S. maltophilia ATCC 13637 was also included. Biochemical identification was performed with the API 20NE (BioMerieux, La Balme Les Grottes, France) and WIDER (Fco. Soria Melguizo, Madrid, Spain) systems. All S. maltophilia strains were typed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (CHEF-DRII system; Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) under XbaI restriction, as described previously (32, 33), to ensure the selection of unrelated isolates.

Quinolone susceptibility and phenotypic characterization of efflux mechanism.

The MICs of nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin were determined by the standard agar dilution method (26), but with a final inoculum of 105 CFU/spot and 24-h incubation period at 35°C (32). Antimicrobial powders were supplied by their corresponding manufacturers. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 and Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 were used as quality controls.

To investigate the presence of an active efflux mechanism, the MICs of nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin were also determined in combination with 0.5 μg of CCCP per ml and 10 μg of reserpine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) per ml. An efflux mechanism was inferred to be present when the quinolone MIC in the presence of CCCP and/or reserpine was at least fourfold less (2 doubling dilutions) than the corresponding MIC in the absence of these compounds.

Amplification and sequence analysis of QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of S. maltophilia.

The primers used to amplify the QRDRs of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE are indicated in Table 1. DNA template was prepared from a loop of a fresh overnight culture suspended in water, followed by boiling for 10 min and centrifugation. Amplification was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 5 μl of DNA template, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, each primer (Pharmacia Biotech, Orsay, France) at a concentration of 2.5 pM, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia) at a concentration of 200 μM, and 5.0 U of Taq polymerase (Roche, Branchburg, N.J.). The reactions were performed on a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn). The samples were denatured at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 amplification cycles with the following parameters: 94°C for 1 min, 54°C at 1 min for annealing, and 72°C at 1 min for polymerization. A final cycle of 72°C for 5 min was used to fully extend the amplicons. The PCR products were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Sequencing of both strands of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE fragments was done with the same primers used for PCR with the Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin-Elmer, Applied Biosystems Division), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The products were resolved and analyzed with an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer. Nucleotide sequences were analyzed by using PCGene software (Inteligenetics Inc.).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of QRDR regions of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE in S. maltophilia strains

| Topo- isomerase gene | Primera | Nucleotide sequence |

|---|---|---|

| gyrA | SMGYRA-F | 5"-AACTCAACGCGCACAGCAACAAGCC-3" |

| SMGYRA-R | 5"-CCAGTTCCTTTTCGTCGTAGTTGGG-3" | |

| gyrB | SMGYRB-F | 5"-GATGACCCGCCGTAAGGGCG-3" |

| SMGYRB-R | 5"-GAAGGTCAGCAGCAGGGTGC-3" | |

| parC | SMPARC-F | 5"-ATCGGCGACGGCCTGAAGCC-3" |

| SMPARC-R | 5"-CGGGATTCGGTATAACGCAT-3" | |

| parE | SMPARE-F | 5"-CCGGCGCTGCCTGGCAAACTG-3" |

| SMPARE-R | 5"-CGCCCAGGCCCTTGAAGCGGG-3" |

F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Statistical methods.

Data were collected and analyzed by use of Epi-Info software (version 6; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga.). Proportions were compared by the χ2 or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. All P values were two tailed; a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequence data reported here have been assigned the following EMBL accession numbers: AJ409325 for the gyrA sequence, AJ409326 for the gyrB sequence, AJ409327 for the parC sequence, and AJ409328 for the parE sequence.

RESULTS

Quinolone susceptibility and phenotypic characterization of efflux mechanism.

The distributions of the ciprofloxacin MICs for the selected unrelated S. maltophilia strains were as follows: 6, 2, 1, 4, 5, 6, 2, 4, and 2 strains were inhibited by ciprofloxacin at 0.12, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 4, 8, 16, 32, and 64 μg/ml, respectively. This MIC distribution did not show the well-defined bimodal structure that is characteristic of other gram-negative organisms in which topoisomerase mutations are involved in quinolone resistance (36).

The ciprofloxacin MICs for 23 strains were unaffected by the presence of 0.5 μg of CCCP per ml. On the contrary, for six strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were 32, 8, 8, 4, 4, and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, the corresponding MICs decreased four to six times in the presence of CCCP (Table 2). With the exception of three strains, CCCP did not decrease the nalidixic acid MICs: for two strains, MICs of 64 μg/ml decreased 8 and 10 times, respectively, whereas for one strain, the MIC of 1 μg/ml decreased 6 times. None of these strains with a positive result in the phenotypic efflux assay were affected by the presence of CCCP (0.5 μg/ml) when they were tested alone. Conversely, three strains with negative results by the phenotypic efflux assay and for which ciprofloxacin MICs were 0.1, 1, and 4 μg/ml, respectively, were unable to grow in the presence of 0.5 μg of CCCP per ml. When reserpine (10 μg/ml) was added to nalidixic acid, no effect was observed. In contrast, in two strains reserpine was able to reduce the ciprofloxacin MICs (0.2 and 0.5 μg/ml) four times. All strains grew on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 10 μg of reserpine per ml.

TABLE 2.

Amino acid changes in GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE QRDR fragments in 32 S. maltophilia clinical strains and quinolone susceptibilities with and without CCCP and reserpine

| Strain (patient origin) | MIC (μg/ml)

|

Amino acid (nucleotides) at indicated positiona

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | Nalidixic acid | GyrA

|

GyrB | ParC, 80 | ParE

|

||||||||||||||||

| 70 | 85 | 90 | 103 | 112 | 113 | 119 | 124 | 407 | 437 | 465 | 477 | 485 | 507 | 525 | 545 | ||||||

| ATCC 13637 | 0.1-2 | 4-8 | Val (GTC) | Val (GTC) | Val (GTC) | Val (GTC) | Ile (ATC) | Asp (GAT) | Ala (GCA) | Glu (GAA) | Ser (AGC) | Asp (GAC) | Met (ATG) | Ile (ATC) | Ser (AGC) | Ile (ATC) | Lys (AAG) | Leu (CTG) | Ser (TCG) | ||

| 10 strainsb | 0.1-64 | 2->128 | —c | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm199 (non-CF) | 0.1 | 8 | — | Gly (GGC) | Glu (GAC) | — | Val (GTC) | — | — | — | — | — | Ser (AGC) | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm196 (CF) | 0.1 | 8 | — | — | — | — | Val (GTC) | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (GTC) | Val (GTG) | Ala (GCC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm202 (non-CF) | 0.1 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTG) | Arg (AGG) | — | — | |

| Sm65 (non-CF) | 0.25 (0.06)d | 1 (0.12)e | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm63 (non-CF) | 0.5 (0.06)e (0.12)d | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm66 (non-CF) | 0.5 | 8 | — | — | — | Ala (GCC) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm36 (CF) | 1 | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Val (GTG) | — | |

| Sm83 (CF) | 1 | 8 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTG) | Arg (AGG) | — | — | |

| Sm24 (CF) | 1 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Ala (GCC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm85 (non-CF) | 1 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Ala (GCC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm230 (CF) | 4 (0.5)e | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Thr (ACG) | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTG) | — | — | — | |

| Sm14 (CF) | 4 | 16 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTC) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTG) | — | — | — | |

| Sm203 (CF) | 4 (1)e | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | His (CAT) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm4 (CF) | 4 | 64 | — | — | — | — | — | — | Gly (GCA) | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTG) | Arg (AGG) | — | — | |

| Sm50 (CF) | 8 (2)e | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm8 (CF) | 8 | 32 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Ala (GCT) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm219 (non-CF) | 8 (2)e | 64 (4)e | — | — | — | — | Val (GTC) | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Ala (GCC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm117 (non-CF) | 16 | 32 | — | — | — | — | Val (GTC) | — | — | — | — | Arg (AGA) | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm98 (CF) | 16 | 128 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTC) | Arg (AGG) | — | — | |

| Sm28 (CF) | 32 (8)e | 64 (2)e | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Thr (ACC) | |

| Sm104 (non-CF) | 32 | 128 | Gly (GGC) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Sm226 (non-CF) | 64 | 128 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | Leu (CTG) | Val (GTG) | Thr (ACC) | Val (GTC) | — | — | — | |

Amino acid position corresponds to the amino acid numbering of the topoisomerase II and IV subunits of E. coli.

Three strains were from CF patients, and seven strains were from non-CF patients.

—, no change with respect to S. maltophilia ATCC 13637 QRDR sequence.

Values in parentheses are MICs in the presence of 10 μg of reserpine per ml. These values are indicated only when the decreases were 2 or more doubling dilutions.

Values in parentheses are MICs in the presence of 0.5 μg of CCCP per ml. These values are indicated only when the decreases were 2 or more doubling dilutions.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of QRDRs of the gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes of S. maltophilia.

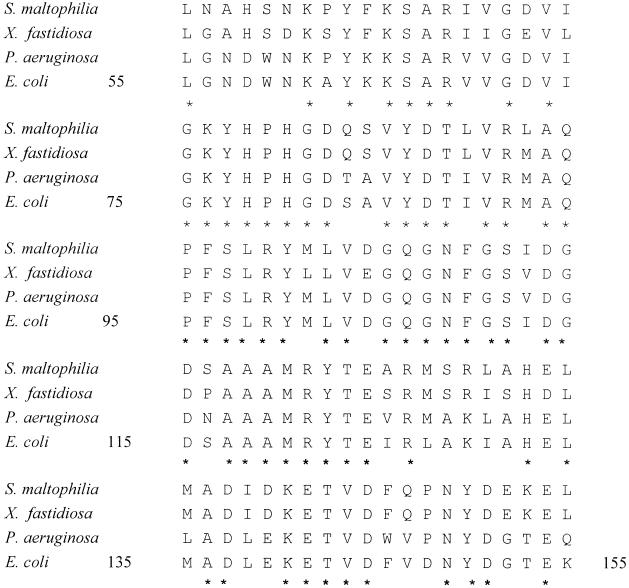

The amplified fragments, including the putative gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE QRDR topoisomerase genes, were directly sequenced. Amplification of the gyrA QRDR resulted in one fragment that was of the predicted size (300 bp) and that corresponded to Leu-55 to Gln-155, according to the E. coli gyrA numbering (Fig. 1). The nucleotide sequence of S. maltophilia gyrA had 76.7 and 73.0% identities to the corresponding fragments from P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively, while the deduced amino acid sequence exhibited 78.0% identity to the amino acid sequences of P. aeruginosa and E. coli GyrA (Fig. 1). Amplification with the SMGYRB primers resulted in several fragments. One of them was of the expected size (300 to 400 bp) and was purified from the agarose gel and sequenced, leading to a 369-bp DNA GyrB fragment that corresponded to Met-391 through Phe-513. The identities of the nucleotide sequence of the S. maltophilia gyrB fragment with those of the P. aeruginosa and E. coli gyrB fragments were 85.4 and 80.2%, respectively. In both cases, the deduced amino acid sequence of the S. maltophilia GyrB fragment showed 88.6% identity with each of the amino acid sequences of the P. aeruginosa and E. coli GyrB fragments.

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequences of GyrA fragments from S. maltophilia ATCC 13637, X. fastidiosa (amino acid sequence identity, 85.0%), P. aeruginosa PAO1 (amino acid sequence identity, 78.0%), and E. coli (amino acid sequence identity, 78.0%). Asterisks indicate conserved residues. The corresponding amino acid sequence identity values for GyrB, ParC, and ParE are provided in the text.

After amplification with the SMPARC primers (Table 1), only one 273-bp DNA fragment was generated (Ile-34 to Arg-124). The parC nucleotide sequence of S. maltophilia had 82.4 and 78.3% identities with the corresponding fragments from P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively. The corresponding amino acid sequence exhibited 84.6 and 88.0% identities with the ParC sequences of P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively. Moreover, amplification with the SMPARE primers resulted in several fragments, of which only one was of the expected size. This fragment was purified from the agarose gel and sequenced, leading to a 519-bp DNA ParE fragment located between amino acid residues Leu-396 and Leu-567. The nucleotide sequence of this fragment had 73.0 and 69.9% identities with the corresponding fragments from P. aeruginosa and E. coli, respectively, whereas the amino acid sequence showed 70.9 and 73.2% identities with the amino acid sequences from these organisms.

Higher degrees of amino acid identity were reached between the S. maltophilia GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE QRDR fragments and those from the phytopathogen Xylella fastidiosa, exhibiting identities of 85.0, 93.5, 89.0, and 88.4%, respectively. Furthermore, the amino acid identities shared between the homologous subunits of topoisomerases II and IV of S. maltophilia were 46.0% for GyrA and ParC and 45.0% for GyrB and ParE.

Amino acid substitutions of the GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE QRDRs in S. maltophilia clinical strains.

Table 2 shows the amino acid substitutions found in the GyrA, GyrB, ParC, and ParE QRDRs compared with the corresponding sequences of S. maltophilia ATCC 13637. Within GyrA, 9 of 32 strains showed amino acid substitutions: eight strains exhibited a single amino acid change, while another strain exhibited three different amino acid changes (Table 2). The effects of these amino acid changes on quinolone susceptibility are unclear, as they were present in strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were different. Six of these strains displayed five different changes (at positions 70, 112, 113, 119, and 124), and ciprofloxacin MICs for these strains ranged from 4 to 64 μg/ml, while for three strains, two of them with a single amino acid substitution (at positions 103 and 112) and one strain with three amino acid substitutions (at positions 85, 90, and 112), ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 0.1 to 1 μg/ml. Moreover, 13 strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 4 to 64 μg/ml did not show any mutations in their gyrA sequences (Table 2). It is noteworthy that only one substitution, Ile-112, appeared in four strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were 0.1, 0.1, 8, and 16 μg/ml, respectively, ruling out its possible role in quinolone resistance. One of these strains (ciprofloxacin MIC, 16 μg/ml) harbored a single amino acid substitution at position 80 of the ParC QRDR, replacing Ser (AGC) for Arg (AGA) (Table 2).

None of the clinical strains harbored amino acid substitutions in the GyrB QRDR when their sequences were compared with the sequence of the corresponding fragment from S. maltophilia ATCC 13637. On the contrary, eight different substitutions (at positions 407, 437, 465, 477, 485, 507, 525, and 545) were identified in the region of ParE from 16 strains studied. Two strains had single amino acid substitutions, six strains had three amino acid substitutions, four strains had four amino acid substitutions, and four strains had five amino acid substitutions (Table 2). It is noteworthy that 14 of 16 strains showed a triple substitution that affected positions 437, 465, and 477. The combination of all replacements led to the appearance of eight different ParE proteins, which showed percentages of divergence compared to the sequence of strain ATCC 13367 that ranged from 0.58% (one amino acid change) to 2.9% (five amino acid changes).

It is worth noting that the frequency of appearance of the ParE substitutions was higher in strains from CF patients than in strains from non-CF patients. This difference was statistically significant for those substitutions located at positions 437, 465, 477, and 485 (P = 0.0325). In contrast, no statistically significant differences in the rates of appearance of these substitutions were found between strains for which ciproploxacin MICs were low (≤1 μg/ml) and high (≥4 μg/ml).

DISCUSSION

Most clinical isolates of S. maltophilia are completely resistant to several antimicrobials (8, 32). Nevertheless, fluoroquinolones are variably active against this organism (32) and have been suggested to be active in vivo against S. maltophilia infections (8). The emergence of resistant strains from an initially susceptible S. maltophilia strain during quinolone therapy has been reported (5). Moreover, in vitro mutants resistant to quinolone may be recovered at frequencies of 10−5 to 10−7 when strains are exposed to these compounds (23), but the mechanism of resistance has not been elucidated. In general, quinolone resistance involves modifications of the topoisomerase II and/or IV subunits, decreases in permeability, and hyperexpression of efflux pumps (16). The last two mechanisms may affect the quinolone susceptibility of S. maltophilia (1, 23, 42), but the increase in quinolone MICs has not been correlated with amino acid substitutions in topoisomerases. To date, several bacterial topoisomerases have been characterized, but not in S. maltophilia. In our study, the amplified products of highly conserved regions in each of the topoisomerase genes of S. maltophilia showed high degrees of identity with the sequences of the topoisomerase genes of other bacteria, particularly those corresponding to X. fastidiosa, another organism of the rhizosphere that causes economically important plant diseases (22).

It has been extensively demonstrated that GyrA is the primary target of most quinolones in gram-negative organisms (16). Amino acid replacements in the QRDR of GyrA (from positions Ala-67 to Gln-106) decrease the levels of susceptibility to these compounds and normally precede amino acid replacements in ParC, which is altered secondarily in resistant strains (16). In addition, modifications to GyrB and ParE have been shown to enhance fluoroquinolone resistance levels (14). Substitutions at positions 83 (Ser→Leu, Trp, Phe, or Tyr and Thr→Ile) and 87 (Asp→Asn, Gly, His, Val, or Tyr) (15, 34) of GyrA are the most common modifications associated with resistance to quinolones (6, 7, 15, 21, 27, 30, 34, 35, 38, 39). These substitutions and those at positions Ala-67, Gly-81, Ala-84, and Gln-106 lead to high nalidixic acid MICs and, to a lesser extent, variably affect ciprofloxacin MICs (13, 24, 41). They commonly replace a polar amino acid by a nonpolar residue that reduces the affinity of the DNA-gyrase complex for the quinolone and that blocks the accessibility of the antimicrobial. It is remarkable that in S. maltophilia ATCC 1367 and in all clinical strains sequenced, Gln instead of Ser or Thr was always identified at position 83, as Ser or Thr is systematically observed in quinolone-susceptible E. coli or P. aeruginosa isolates, respectively (6, 21). This substitution could explain the lower levels of intrinsic activity of the quinolones against S. maltophilia when the MICs are compared with those obtained for E. coli.

The effects of amino acid changes in GyrA on quinolone susceptibility in S. maltophilia are unclear. None of the strains showed amino acid changes at any of the positions at which changes are commonly described in other organisms. Moreover, the same Ile-112→Val change was observed in four strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were 0.1, 0.1, 8, and 16 μg/ml, respectively. However, the role of changes at positions 70, 113, 119, and 124 merits further studies, as they were identified only in S. maltophilia strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 4 to 32 μg/ml (Table 2). It is noteworthy that one strain (strain Sm230) had an amino acid substitution at position 119 (Ala-119→Thr). This position is outside the standard region of the GyrA QRDR, but similar changes (Ala-119→Glu or Val) have been identified as contributing to nalidixic acid resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (12). The potential role of substitutions outside the limits of the QRDR in quinolone resistance has recently been explored in both gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, leading to the conclusion that the QRDR should be expanded (10, 17).

As stated previously, amino acid changes in the QRDR of ParC may also contribute to fluoroquinolone resistance in gram-negative organisms (14). These changes are usually detected when GyrA substitutions are present (14, 20) and have been described at positions 80 and 84, analogous to positions 83 and 87 of GyrA, respectively (14). In our collection, contrary to the amino acid substitutions detected in P. aeruginosa and other organisms, none of the strains displayed amino acid substitutions at position 84. Furthermore, only one strain (strain Sm117) showed an amino acid replacement at position 80 (Ser-80→Arg), which partially differed from those characterized in E. coli (Ser-80→Ile or Arg) (14, 20) or P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii (Ser-80→Leu) (34). This strain, for which the ciprofloxacin MIC was 16 μg/ml, also harbored an Ile-112 substitution in GyrA, a change that was also present in two strains for which the ciprofloxacin MIC was 0.06 μg/ml. This finding makes it difficult to understand the possible role of the Ser-80 substitution in ParC in the increase in the ciprofloxacin MIC.

GyrB and ParE modifications may also enhance fluoroquinolone resistance levels (2, 4, 19, 27, 28). Although GyrB amino acid changes have been identified in E. coli (Asp-426→Asn, Lys-447→Glu) (40), S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (Ser-463→Tyr) (11), and P. aeruginosa (Ser-464→Phe) (25), none of the fragments amplified from the S. maltophilia strains showed any replacements. In contrast to this conserved sequence, replacements were found in the ParE sequences of 16 (50%) strains, and in 7 of these strains they were detected simultaneously with GyrA replacements (Table 2). Moreover, these substitutions were statistically associated (P < 0.05) with strains recovered from CF patients.

The possible role of the ParE replacements on quinolone resistance differs between investigators. Studies with both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms show that changes at residues 420, 435, 445, and 458 of ParE decreased quinolone susceptibility (2, 4, 9, 19, 28), whereas other investigators failed to detect this association (18). Nevertheless, amino acid changes (Table 2) identified in the region of S. maltophilia ParE studied are different from those clearly involved in quinolone resistance. In addition, the frequency of appearance of ParE substitutions in strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs are high (4 to 64 μg/ml) compared with the frequency of appearance of substitutions in strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs are low (0.06 to 1 μg/ml) was shown by the chi-square test to be not statistically linked.

On the other hand, our study also screened for the contribution of efflux mechanisms to the fluoroquinolone susceptibility of S. maltophilia. To date, two independent studies have confirmed the involvement of efflux systems in the multidrug resistance phenotype of this organism (1, 42). These systems, mostly studied in mutants generated with tetracycline in vitro, are inhibited by CCCP and seem to affect quinolone, chloramphenicol, and tetracycline compounds and, to a lesser extent, β-lactams. Moreover, their effects on aminoglycosides are variable (1, 42). In our study, an efflux-positive phenotype was suggested when nalidixic acid or ciprofloxacin MICs were decreased at least four times (twofold dilutions) in the presence of a proton motive uncoupler compound (CCCP) and/or the alkaloid reserpine. Such a phenotype was observed in seven S. maltophilia strains for which tetracycline and chloramphenicol MICs were also high (range of tetracycline MICs, 32 to >128 μg/ml; range of chloramphenicol MICs, 16 to >64 μg/ml) (data not shown). For these seven strains ciprofloxacin MICs ranged from 0.25 to 32 μg/ml (Table 2). Of note is the fact that this phenotype was present both in S. maltophilia strains with GyrA amino acid substitutions (3 of 9 strains) and in those with no amino acid substitutions (4 of 23 strains) (Table 2). Independently, the efflux phenotype was suggested to be more efficient with the CCCP and ciprofloxacin combination than with the other combinations tested. Reserpine was able to decrease the ciprofloxacin MICs only 2 dilutions for 2 strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were 0.25 and 0.5 μg/ml, respectively, and just 1 dilution for 11 strains. This compound has been used to identify efflux phenotypes both in gram-positive organisms, particularly Streptococcus pneumoniae (29), and in gram-negative organisms, including A. baumannii (3). It has been reported that reserpine is able to decrease the fluoroquinolone MICs for these organisms, but this was not the case in our study.

In summary, the topoisomerase subunits from S. maltophilia showed higher degrees of identity with the corresponding fragments from X. fastidiosa than with those from E. coli or P. aeruginosa. A clear predominance of ParE replacements (in 16 of 32 strains) over GyrA (9 strains), ParC (1 strain), and GyrB (none of the strains) replacements was found. The relationship of a specific replacement with quinolone resistance is unclear, as these substitutions were identified both in strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were low (0.1 to 1 μg/ml) and in strains for which ciprofloxacin MICs were high (4 to 64 μg/ml). Complementary studies would be necessary to ascertain the influences of these substitutions on quinolone susceptibility. Moreover, the presence of an efflux-based phenotype, as determined by screening with CCCP, was also suggested for a few strains. In contrast to the findings for other gram-negative organisms, our results demonstrate the complexity of fluoroquinolone resistance in S. maltophilia, in which the adaptive efficacy of efflux and perhaps other complementary mechanisms may have prevented the emergence of mutations in topoisomerases.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Gómez, P. Martín, and L. C. Antón for technical assistance with DNA sequencing.

This research was supported by grant 2114/98 from the Consejería de Educación y Ciencia, Comunidad de Madrid, Madrid, Spain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alonso, A., and J. L. Martinez. 2001. Expression of multidrug efflux pump SmeDEF by clinical isolates of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1879-1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bebear, C. M., J. Renaudin, A. Charron, H. Renaudin, B. Barbeyrac, T. Schaeverbeke, and C. Bebear. 1999. Mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE genes associated with fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Mycoplasma hominis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:954-956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bou, G., G. Cerveró, M. A. Domínguez, C. Quereda, and J. Martínez-Beltrán. 2000. Characterization of a nosocomial outbreak caused by a multiresistant Acinetobacter baumannii strain with a carbapenem-hydrolyzing enzyme: high-level carbapenem resistance in A. baumannii is not due solely to the presence of β-lactamases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3299-3305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breines, D. M., S. Ouadbesselam, E. Y. Ng, J. Tankovic, S. Dhah, C. J. Soussy, and D. C. Hooper. 1997. Quinolone resistance locus nfxD of Escherichia coli is a mutant allele of the parE gene encoding a subunit topoisomerase IV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:175-179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng, A. F., M. K. W. Li, T. K. W. Ling, and G. L. French. 1987. Emergence of ofloxacin-resistant Citrobacter freundii and Pseudomonas maltophilia after ofloxacin therapy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 20:283-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullen, M. E., A. W. Wyke, R. Kuroda, and L. M. Fisher. 1989. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase gyrA gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:886-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dekitsch, C., R. Schein, E. Markopoulos, B. Kuen, W. Graninger, and A. Georgopoulos. 1999. Analysis of mutations to gyrA in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:73-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Denton, M., and K. G. Kerr. 1998. Microbiology and clinical aspects of infection associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:57-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fournier, B., and D. C. Hooper. 1998. Mutations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase of Staphylococcus aureus: novel pleiotropic effects on quinolone and coumarin activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:121-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman, M. S., T. Lu, and K. Drlica. 2000. Mutation in the DNA gyrase A gene of Escherichia coli that expands the quinolone resistance-determining region. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2378-2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gensberg, K., Y. F. Jin, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1995. A novel gyrB mutation in a fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolate of Salmonella typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 132:1741-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griggs, D. J., K. Gensberg, and L. J. V. Piddock. 1996. Mutations in gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant Salmonella serotypes isolates from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 40:1009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hallet, P., and A. Maxwell. 1991. Novel quinolone resitance mutations of Escherichia coli DNA gyrase A protein: enzymatic analysis of the mutant proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:335-340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heisig, P. 1996. Genetic evidence for a role of parC mutations in development of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:879-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heisig, P., H. Schedletzky, and H. Falkenstein-Paul. 1993. Mutations in gyrA gene of a highly fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:696-701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper, D. C. 1999. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance. Drug Resist. Update 2:38-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ince, D., and D. C. Hooper. 2000. Mechanisms and frequency of resistance to premafloxacin in Staphylococcus aureus: novel mutations suggest novel drug-target interactions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3344-3350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones, M. E., D. F. Sahm, N. Martin, S. Scheuring, P. Heisig, C. Thornsberry, K. Köhrer, and F. J. Schmitz. 2000. Prevalence of gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE mutations in clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae with decreased susceptibilities to different fluoroquinolones and originating from worldwide surveillance studies during 1997-1998 respiratory season. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:462-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen, J. H., L. M. Weigel, M. J. Ferraro, J. M. Swenson, and F. C. Tenover. 1999. Activities of newer fluoroquinolones against Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates including those with mutations in the gyrA, parC, and parE loci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:329-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumagai, Y., J. I. Kato, K. Hoshino, T. Akasaka, K. Sato, and H. Ikeda. 1996. Quinolone resistant mutants of Escherichia coli DNA topoisomersase IV parC gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:710-714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kureishi, A., J. M. Diver, B. Beckthold, T. Schollaardt, and L. E. Bryan. 1994. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa DNA gyrase gyrA gene from strain PAO1 and quinolone-resistant clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1944-1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lambais, M. R., M. H. Goldman, L. E. Camargo, and G. H. Goldman. 2000. A genomic approach to the understanding of Xylella fastidiosa pathogenity. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3:459-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecso-Bonet, M., J. Pierre, D. Sarkis-Karam, S. Lubera, and E. Bergone-Bérézin. 1992. Susceptibility of Xanthomonas maltophilia to six quinolones and study of outer membrane proteins in resistant mutants selected in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36:669-671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moniot-Ville, N., J. Guibert, N. Moreau, J. F. Acar, E. Collatz, and L. Gutmann. 1991. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli highly resistant to fluoroquinolones but susceptible to nalidixic acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:519-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mouneimné, H., J. Robert, V. Jarlier, and E. Cambau. 1999. Type II topoisomerase mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:62-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. 2001. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 11th informational supplement, vol. 20, no.1. Document M100-S11. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Wayne, Pa.

- 27.Oram, M., and L. M. Falkenstein-Paul. 1991. 4-Quinolone resistance mutations in the DNA gyrase of Escherichia coli clinical isolates identified by using the polymerase chain reaction. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:387-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perichon, B., J. Tankovic, and P. Courvalin. 1997. Characterization of a mutation in the parE gene that confers fluoroquinolone resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:2810-2816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piddock, L. J., M. Johnson, V. Ricci, and S. L. Hill. 1998. Activities of newer fluoroquinolones against fluoroquinolone-resistant pathogens of the lower respiratory tract. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2956-2960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz, J., D. Castro, P. Goñi, J. A. Santamar&ıacute;a, J. J. Borrego, and J. Vila. 1997. Analysis of the mechanism of quinolone resistance in nalidixic acid-resistant clinical isolates of Salmonella serotype Typhimurium. J. Med. Microbiol. 46:623-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein, G. E. 1996. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of newer fluoroquinolones. Clin. Infect. Dis. 23(Suppl. 1):S19-S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valdezate, S., A. Vindel, E. Loza, F. Baquero, and R. Cantón. 2001. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of unique Stenotrophomonas maltophilia clinical strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:1581-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Valdezate, S., A. Vindel, L. Maiz, F Baquero, H. Escobar, and R. Cantón. 2001. Persistence and variability of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in cystic fibrosis patients, Madrid, 1991-1998. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:113-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, P. Goñi, and T. Jimenez de Anta. 1997. Quinolone-resistance mutation in the topoisomerase IV parC gene of Acinetobacter baumannii. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 39:757-762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, P. Goñi, A. Marcos, and T. Jimenez de Anta. 1995. Mutation in the gyrA gene of quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1201-1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vila, J., J. Ruiz, F. Marco, A. Barcelo, P. Goni, E. Giralt, and T. Jimenez de Anta. 1994. Association between double mutation in gyrA gene of ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and MICs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:2477-2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang, J. C. 1996. DNA topoisomerases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65:635-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang, Y., W. M. Huang, and D. E. Taylor. 1993. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of Campylobacter jejuni gyrA gene and characterization of quinolone resistance mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:457-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1271-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, L. M. Yamakana, and S. Nakamura. 1991. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrB gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:1647-1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida, H., M. Nakamura, M. Bogaki, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Proportion of DNA gyrase mutants among quinolone-resistant strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1273-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, L., X. Z. Li, and K. Poole. 2000. Multiple antibiotic resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: involvement of a multidrug efflux system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:287-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]