Abstract

Transient kinetic studies with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 reverse transcriptase suggest that nucleotide analogs containing the 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy ribose ring structure present in D4T (stavudine) triphosphate are among the most effective alternative substrates. For unclear reasons, however, the corresponding purine nucleoside, 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine (D4G), was found to be inactive in cell culture. We have found that the previously reported lack of activity of D4G is primarily due to solution instability, and in this report we describe a novel use of a guanosine prodrug approach to stabilize the nucleoside. D4G was modified at the 6 position of the purine ring to contain a cyclopropylamino group yielding the prodrug, cyclo-D4G. An evaluation of cyclo-D4G revealed that the prodrug possessed anti-HIV activity. In addition, cyclo-D4G had increased stability, lipophilicity, and solubility, as well as decreased toxicity relative to D4G, suggesting that further study is warranted.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), the causative agent of AIDS, requires reverse transcriptase (RT) to copy its single-stranded RNA genome into a double-stranded DNA copy for integration into the host cell genome. To date, some of the most successful drugs at treating HIV are nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), which lack a 3′-hydroxyl group and serve to chain terminate viral replication after activation by cellular kinases. However, treatment with NRTIs is limited by their toxicity to the host (often because of their interaction with mitochondrial polymerase γ [9, 20]) and the ability of the virus to mutate and gain resistance (3, 14). In order to avoid the appearance of resistant virus, highly active antiretroviral therapy has been used, which includes multidrug combinations (11). However, mutants resistant to combinations of presently available compounds have still arisen (19). In order to further our ability to treat HIV, new compounds are needed with different metabolism, resistance, and toxicity profiles to supplement agents presently available.

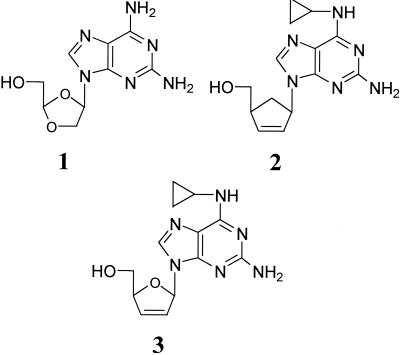

Recently, a guanosine prodrug approach has proven successful in improving the pharmacokinetics of already potently active guanosine NRTIs. The guanine ring of both dioxolane guanosine (DXG) (12) and carbovir (CBV) (26) were functionalized at the 6 position with an amine to make diaminopurine dioxolane (DAPD; compound 1) (1) and abacavir (1592U89 or Ziagen; compound 2) (5), respectively (Fig. 1). Abacavir and DAPD are metabolized to guanosine analogs by deamination and phosphorylated to make the active triphosphates (6, 7). The presence of the amino group improved the lipophilicity, solubility, and oral bioavailability of these guanosine analogs (1, 5). The presence of the cyclopropyl-substituted secondary amine of abacavir also improved its absorption into the central nervous system (5).

FIG. 1.

Structures of guanosine prodrug nucleoside analogs: DAPD (compound 1), abacavir (compound 2), and cyclo-D4G (compound 3).

Transient kinetic studies have been used to provide insight into structural modifications of the ribose ring, which are well tolerated by HIV-1 RT (7, 10, 21, 25). In a study on the incorporation of D4T triphosphate (D4TTP) by HIV-1 RT into physiologically relevant primer/templates, it was found that D4TTP is incorporated as efficiently as the natural substrate dTTP (25). The inability of RT to distinguish between D4TTP and the natural substrate may be responsible for D4T's limited selection of resistance mutations in vitro (13) and in vivo (8). Similar studies with the active metabolites of the two presently clinically relevant guanosine prodrug analogs have shown that DXGTP and CBVTP are incorporated approximately an order of magnitude less efficiently than dGTP (7, 21). This decreased efficiency of incorporation may suggest slight differences in the way that these analogs interact with RT versus the natural deoxynucleoside triphosphate that could be taken advantage of during the selection of resistant mutants (25). Taken together, these studies suggest that a guanosine analog with the same 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy ribose ring structure as D4TTP (2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxyguanosine [D4G] TP) would be a better inhibitor than CBV triphosphate and DXG triphosphate at the RT active site, both as a better substrate and possibly with respect to the development of resistance.

The kinetic prediction that D4G triphosphate would be a superior inhibitor of RT has not been tested, although at a cellular level, the nucleoside D4G has previously been reported to show no anti-HIV activity (2). This report, however, did not elucidate the reason for the lack of antiviral activity for D4G, and clearly many factors, such as solubility, stability, and metabolism may play a role. An ancillary question is if D4G is, in fact, inactive in cell culture, could it be activated by the use of a guanosine prodrug approach? In order to address these questions and gain a better understanding of the guanosine prodrug approach, D4G and a 6-substituted prodrug (cyclo-D4G; compound 3) (Fig. 1) were synthesized and evaluated in a number of in vitro assays to assess stability, toxicity, and anti-HIV activity.

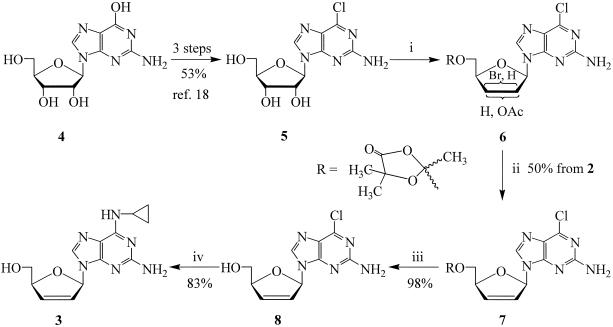

Synthesis of Cyclo-D4G.

Cyclo-D4G 3 was synthesized from guanosine in seven steps (Fig. 2). 2-Amino-6-chloro-9-β-d-ribofuranosyl-purine 5 was prepared from guanosine 4 in three steps (18). Compound 5 was treated with α-acetoxyisobutyryl bromide to give a mixture of 2′-acetoxy-3′-bromo and 3′-acetoxy-2′-bromo derivative 6, which was treated with activated zinc to obtain compound 7. Deprotection of compound 7 with K2CO3 in MeOH/H2O gave the free nucleoside 8 (22), which was treated with cyclopropylamine in ethanol to afford target compound 3 [2-amino-6-cyclopropylamino-9-(2′,3′-dideoxy-β-d-glycero-pent-2-enofuranosyl) purine, cyclo-D4G] as a foam in 83% yield (4): [α]24D −16.4° (c 0.64, MeOH); UV (MeOH): 284 (ɛ 1.3 × 104), 260 (ɛ 8.6 × 103), 224 (ɛ 1.8 × 104); 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 0.61 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.82 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.95 (brs, 1H, CH), 3.30 (brs, 1H, 5′-OH), 3.84 (dd, J = 2.8, 12.8 Hz, H-5′a), 4.04 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, H-5′b), 5.06 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, H-4′), 5.21 (brs, 2H, NH2), 5.93 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H, H-2′, and H-N6), 6.39 (dd, J = 1.4, 6.0 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 6.70 (d, J = 1.6 Hz, H-1′), and 7.49 (s, 1H, H-8); HRMS (FAB) (M + 1)+m/z calculated for C13H17N6O2: 289.1439, found: 289.1422; anal. calculated for C13H16N6O2·0.3H2O: C, 53.06; H, 5.71; N, 28.56; found: C, 53.27; H, 5.65; and N, 28.47.

FIG. 2.

Synthesis of cyclo-D4G (compound 3). (i) (CH3)2C(OAc)COBr/CH3CN. (ii) Zn/DMF. (iii) K2CO3/H2O/MeOH. (iv) Cyclopropylamine/C2H5OH.

Solubility and lipophilicity of D4G and cyclo-D4G.

Cyclo-D4G was far more soluble in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) than was D4G. Concentrations of >60 mM cyclo-D4G could be achieved in stock solutions, while D4G was soluble only up to 5 mM. Lipophilicity of these compounds was based upon their retention times during reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography using a BDS Hypersil C-18 reverse-phase column (Keystone Scientific) and isocratic gradient (80% 200 mM triethyl ammonium bicarbonate and 20% methanol; flow rate, 1 ml/min). It was found that cyclo-D4G had much higher affinity for the C-18 column than D4G (retention times: deoxyguanosine [dG], 3 min, D4G, 5 min; and cyclo-D4G, 16 min). These features may serve to increase the bioavailability and overall pharmacokinetic profile of cyclo-D4G over D4G; however, animal experimentation will be required to confirm this suggestion.

Anti-HIV activity and toxicity in MT-2 cells.

D4G and cyclo-D4G were compared to other nucleoside analogs in their activity against HIV-1 (human T-cell leukemia virus IIIB; R. C. Gallo) and cytotoxicity in MT-2 cells (human T-cell leukemia virus-infected human T lymphoblastoid) by previously reported methods (15). The amount of NRTI required to inhibit 50% of HIV infection (50% effective concentration) ranged from 0.27 μM dideoxycytosine (ddC) to 18 μM dideoxyinosine (ddI; data summarized in Table 1). Consistent with previous results, D4G showed no activity when dissolved in distilled water (dH2O) (2); however, when dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), it was found to have anti-HIV activity. Surprisingly, D4G's lack of antiviral activity when dissolved in dH2O was accompanied by a twofold increase in toxicity. Similar to results found for other nucleoside/prodrug combinations (CBV and abacavir and published results for DXG and DAPD [7]), D4G showed twofold-higher activity (when dissolved in PBS) than did cyclo-D4G. These differences in parent versus prodrug activities may be related to a number of factors, including the abilities of the compounds to be metabolized to their respective active triphosphate forms. Interestingly, cyclo-D4G was found to be more than twofold less toxic when compared to D4G. This was in contrast to results obtained with abacavir and CBV, where it was found that the prodrug was more toxic in cell culture.

TABLE 1.

Anti-HIV activity and toxicity in MT-2 cellsa

| Nucleoside | Results for MT-2

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (μM) | IC50 (μM) | nb | |

| ddC | 0.27 ± 0.03 | 4 ± 1.4 | 3 |

| ddI | 18 ± 4 | >>100 | 3 |

| DAPD | 10 ± 4 | >>100 | 3 |

| CBV | 1.1 ± 0.1 | >100 | 3 |

| Abacavir | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 52 ± 10 | 4 |

| D4T | 2.8 ± 0.7 | >100 | 8 |

| D4G (dH2O) | ND | 16 ± 2 | 4 |

| D4G (PBS) | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 47 ± 14 | 10 |

| Cyclo-D4G | 8.6 ± 1.3 | >100 | 12 |

Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

n = number of independent trials done in triplicate.

ND = no detectable anti-HIV activity.

EC50 = 50% effective concentration.

Stability at pH 2, 7.4, and 11

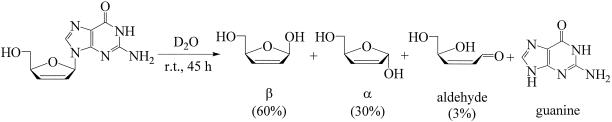

The solvent-dependent activity and toxicity of D4G suggest that it is unstable under certain conditions and most likely breaks down by an acid-catalyzed depurination. To further study the pH dependence on stability, compounds were dissolved in solutions buffered to pH 2, 7.4, and 11 (using PBS or triethyl ammonium bicarbonate) and their breakdown was observed over time. Samples at pH 2 were analyzed over 300 min using thin-layer chromatography using CH2Cl2/MeOH as a mobile phase. Samples at pH 7.4 and 11 were analyzed over longer time courses using thin-layer chromatography, and results for D4G and cyclo-D4G were verified using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (as described above). Results showed that all compounds were labile at pH 2 but that D4G was greater than an order of magnitude less stable than ddI and cyclo-D4G (Table 2). All compounds were stable under basic conditions. Further study of the breakdown using NMR showed that D4G depurinated in D2O (pH 6.3), forming three distinct sugar species and guanine (Fig. 3). This would explain D4G's lack of activity in lab water (pH 5 to 6) and activity in buffered solution (PBS, pH 7.4). The reason for cyclo-D4G's increased stability over D4G is more likely due to the 6-cyclopropylamino group of cyclo-D4G being less electron withdrawing than the 6-carbonyl group of D4G, which makes cyclo-D4G more stable than D4G under acidic conditions. Results showed that degraded D4G is more toxic to MT-2 cells than the parent intact nucleoside. Guanine is not toxic enough on its own to explain the toxicity of degraded D4G (50% infective concentrations [IC50s] of 90 and 15 μM, respectively), suggesting that the depurinated aldose sugar moiety may be contributing considerable toxicity. A closer inspection of the structure of the sugar by-product reveals that the acyclic open form is a highly active, α, β-unsaturated, Michael acceptor (Fig. 3), which could react with nucleophilic groups on proteins and other cellular components causing toxicity. It is also possible that the cyclic closed sugar ring interferes with nucleoside biosynthesis pathways.

TABLE 2.

Stability of nucleoside analogs

| Nucleoside | Stability (t1/2 in min)c at pH of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.0 | 7.4 | 11 | |

| ddI | 30 | Stablea | Stable |

| D4G | <2.0 | 6,000b | Stable |

| Cyclo-D4G | 40 | Stable | Stable |

Stable = no breakdown observed after 24 h.

Value estimated by extrapolating from 10% breakdown after 24 h.

t1/2, half-life.

FIG. 3.

Acid hydrolysis of D4G determined by NMR. 1H NMR of decomposed D4G (D2O): δ = 7.81 (H-8 of guanine), 7.39 (0.03H, H-1 of aldehyde), 6.32 (0.03H, H-2 of aldehyde), 6.28 (0.03H, H-3 of aldehyde), 6.08 (m, 1H, H-1 of α and β), 6.00 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 0.6H, H-3 of β), 5.94 (s, 0.3H, H-3 of α), 5.84 (m, 1H, H-2 of α and β), 4.93 (s, 0.6H, H-4, of β), 4.71 (s, 0.3H, H-4 of α), 3.77 to 3.58 (m, 2H, H-5).

Cytotoxicity in various cell types

Similar to experiments done in MT-2 cells, toxicity studies were done in Molt-4 (human peripheral blood, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ATCC CRL 1582), CEM (human T lymphoblastoid, ATCC CCL 119), Hep-G2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma, ATCC HB 8065), Vero (monkey kidney, ATCC CRL 1586), 293 (human transformed primary embryonic kidney, ATCC CRL 1573), KB (human oral carcinoma, ATCC CCL 17), and HeLa (human cervical carcinoma, ATCC CCL 2) cells. 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide dye (MTT; Sigma; catalog no. M-2128) was used to access cell viability, and then results were verified by manual cell counting. In all cases the two results were similar, except for cells treated with abacavir where the MTT dye underestimated the toxicity by twofold (see discussion below). Once again D4G (dissolved in PBS) was found to be more toxic than cyclo-D4G in all cell lines tested. In general, D4G was one of the more toxic compounds tested (in most cases second only to ddC), while cyclo-D4G showed intermediate-to-low toxicity. Furthermore, it is interesting that results in T-cell-, liver-, and kidney-derived cells would suggest that cyclo-D4G would be well tolerated by these often nucleoside-sensitive cells and tissues (results summarized in Table 3).

TABLE 3.

IC50s (in micromolars) for nucleoside analogs in various cell typesa

| Nucleoside | Cell type

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molt-4 | CEM | Hep-G2 | Vero | 293 | KB | HeLa | |

| ddC | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 1 | 25 ± 2 | 50 ± 10 | >100 | 100 ± 11 | >100 |

| ddI | NTb | >500 | >500 | NT | NT | >500 | 500 ± 33 |

| DAPD | NT | >500 | 500 ± 33 | NT | NT | >500 | 500 ± 33 |

| Abacavir | 18 ± 3 | 200 ± 50 | 180 ± 12 | 480 ± 100 | 500 ± 75 | 200 ± 21 | 500 ± 33 |

| D4T | 55 ± 8 | 190 ± 30 | 390 ± 26 | >500 | 500 ± 75 | 450 ± 47 | 480 ± 31 |

| D4G (PBS) | 35 ± 10 | 70 ± 11 | 280 ± 19 | 200 ± 40 | 180 ± 30 | >500 | 200 ± 13 |

| Cyclo-D4G | 75 ± 11 | 200 ± 31 | >500 | 350 ± 70 | 400 ± 60 | >500 | 500 ± 33 |

Data obtained from one experiment using MTT dye to quantitate viable cells done in triplicate and verified by an independent experiment using manual cell counting. Values represent mean ± standard deviation.

NT = not tested.

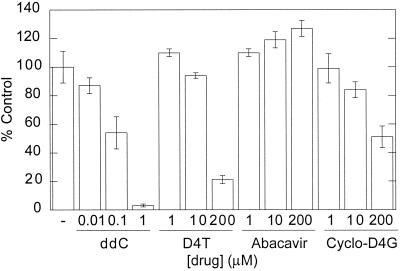

Effect of nucleoside analogs on mitochondrial DNA content

To specifically address the issue of mitochondrial toxicity of D4G and cyclo-D4G relative to other FDA-approved NRTIs (ddC, D4T, and abacavir), CEM cells were grown in the presence of drug for 8 days and the amount of mitochondrial DNA was quantitated using previously reported methods (16). Data for D4G's effects on mitochondrial DNA content could not be obtained because of D4G's high level of general toxicity in these cells. However, at concentrations up to 50 μM, no decrease in mitochondrial DNA was detected, suggesting that D4G's toxicity is not due to mitochondrial damage. The compounds showed the following order in their ability to decrease the amount of mitochondrial DNA: ddC ≫ D4T > cyclo-D4G ≫ abacavir (data summarized in Fig. 4). Abacavir showed a slight, but significant, increase in the amount of mitochondrial DNA at high concentrations. Interestingly, measuring cell viability by the use of MTT dye, which is metabolized by a mitochondrial enzyme (24), was found to underestimate the level of abacavir toxicity (results described above). One might speculate, based upon these results, that abacavir increases the number of mitochondria per cell, although the physiological significance of this observation is unclear. Cyclo-D4G showed significantly more mitochondrial DNA at 200 μM than did D4T (51% versus 21% of control, respectively).

FIG. 4.

Bar graph showing the amount of mitochondrial DNA after incubation with different concentrations of various drugs. Each bar represents the mean ± standard deviation for two independent experiments done in triplicate.

Conclusions.

In this study it was found that the addition of the 6-cyclopropylamine substitution to D4G imparted a high degree of acid stability that the parent compound lacks. This increase in stability led to cyclo-D4G having stability similar to that of ddI, an NRTI presently used in the clinic. The enhanced solution stability for cyclo-D4G over D4G under acidic conditions provides an explanation for previous studies suggesting that D4G lacks antiviral activity. The use of a prodrug approach to improve solution stability in an acidic environment as in cyclo-D4G has not been previously noted for other guanosine prodrugs and may be of general utility in the development of other guanosine analogs. Stability also appears to be of importance in the toxicity of cyclo-D4G and D4G. In this study it was found that degraded D4G was more toxic than the intact nucleoside. It was also found that the more stable cyclo-D4G was less toxic than its more labile parent compound. Our preliminary evidence suggests that the underlying reason for D4G's toxicity may be related to the formation of a 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy ribose ring by-product of an acid-catalyzed depurination. Due to the presence of this same ribose moiety in other clinically relevant compounds, its possible toxicity should be taken into account in further drug development. Indeed studies on fluorinated cytidine analogs, which are also prone to a similar breakdown mechanism, have shown unexpectedly high toxicity (17, 23) that may be related to observations made in this study.

Although D4G was found to be active under buffered conditions, its acid instability, high toxicity, and low solubility make it a poor drug candidate. In a novel use of the guanosine prodrug approach, the prodrug of D4G, cyclo-D4G, was found to have increased stability and lower toxicity. Cyclo-D4G also displayed other advantages relative to D4G that have been previously noted for other guanosine prodrugs, including increased water solubility and lipophilicity with only a slight decrease in anti-HIV activity. The results shown here warrant the further study of cyclo-D4G (and other 6-substituted D4G derivatives) as potential clinically relevant compounds. One interesting possibility is that the unique combination of a 2′,3′-didehydro-2′, 3′-dideoxy ribose ring with a functionalized guanine base could prove useful in combination therapy.

Acknowledgments

K.S.A. is supported by NIH grant GM49551. A.S.R. is supported by NIH, National Research Service Award 5 T32 GM07223 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. C.K.C. is supported by NIH grant AI25899.

We sincerely appreciate help from members of Yung Chi Cheng's laboratory at Yale University: Ginger E. Dutschman for providing HIV-1 viral stocks and for training in biohazard level 3 laboratory practices and Elizabeth Gullen for sharing expertise in the mitochondrial DNA inhibition assay and providing various cell lines for toxicity studies. We thank William B. Parker at Southern Research Institute for the generous gift of CBV.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen, H., R. F. Schinazi, P. Rajagopalan, Z. Gao, C. K. Chu, H. M. McClure, and F. D. Boudinot. 1999. Pharmacokinetics of (-)-beta-D-dioxolane guanine and prodrug (-)-beta-D-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane in rats and monkeys. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 15:1625-1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chu, C. K., R. F. Schinazi, B. H. Arnold, D. L. Cannon, B. Doboszewski, V. B. Bhadti, and Z. Gu. 1988. Comparative activity of 2′,3-saturated and unsaturated pyrimidine and purine nucleosides against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Biochem. Pharm. 37:3543-3548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coffin, J. M. 1995. HIV population dynamics in vivo: implications for genetic variation, pathogenesis, and therapy. Science 267:483-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crimmins, M. T., and B. W. King. 1996. An efficient asymmetric approach to carbocyclic nucleosides: asymmetric synthesis of 1592U89, a potent inhibitor of HIV reverse transcriptase. J. Org. Chem. 61:4192-4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daluge, S. M., S. S. Good, M. B. Faletto, W. H. Miller, M. H. St. Clair, L. R. Boone, M. Tisdale, N. R. Parry, J. E. Reardon, R. E. Dornsife, D. R. Averett, and T. A. Krenitsky. 1997. 1592U89, a novel carbocyclic nucleoside analog with potent, selective anti-human immunodeficiency virus activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1082-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faletto, M. B., W. H. Miller, E. P. Garvey, M. H. St. Clair, S. M. Daluge, and S. S. Good. 1997. Unique intracellular activation of the potent anti-human immunodeficiency virus agent 1592U89. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1099-1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furman, P. A., J. Jeffrey, L. L. Kiefer, J. Y. Feng, K. S. Anderson, K. Borroto-Esoda, E. Hill, W. C. Copeland, C. K. Chu, J.-P. Sommadossi, I. Liberman, R. F. Schinazi, and G. R. Painter. 2001. Mechanism of action of 1-β-d-2,6-diaminopurine dioxolane, a prodrug of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 inhibitor 1-β-d-dioxolane guanosine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:158-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurst, M., and S. Noble. 1999. Stavudine: an update of its use in the treatment of HIV infection. Drugs 58:919-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson, A. A., A. S. Ray, J. W. Hanes, Z. Suo, J. M. Colacino, K. S. Anderson, and K. A. Johnson. 2001. Toxicity of antiviral nucleoside analogs and the human mitochondrial DNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 28:40847-40857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson, K. A. 1992. Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. Enzymes 20:1-61. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson, V. A. 1996. Combination therapy for HIV-1 infection--overview: preclinical and clinical analysis of antiretroviral combinations. Antivir. Res. 29:35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim, H. O., R. F. Schinazi, S. Nampalli, K. Shanmuganathan, D. L. Cannon, A. J. Alves, L. S. Jeong, J. W. Beach, and C. K. Chu. 1993. 1,3-Dioxolanylpurine nucleosides (2R,4R) and (2R,4S) with selective anti-HIV-1 activity in human lymphocytes. J. Med. Chem. 36:30-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lacey, S. F., and B. A. Larder. 1994. Novel mutation (V75T) in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase confers resistance to 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxythymidine in cell culture. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1428-1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larder, B. A. 1994. Interactions between drug resistance mutations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase. J. Gen. Virol. 75:951-957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, T. S., M. Z. Luo, M. C. Liu, S. B. Pai, G. E. Dutschman, and Y. C. Cheng. 1994. Antiviral activity of 2′,3′-dideoxy-beta-L-5-fluorocytidine (beta-L-FddC) and 2′,3′-dideoxy-beta-L-cytidine (beta-L-ddC) against hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vitro. Biochem. Pharmacol. 47:171-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin, T. S., M. Z. Luo, M. C. Liu, S. B. Pai, G. E. Dutschman, and Y. C. Cheng. 1994. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2′,3′-dideoxy-L-pyrimidine nucleosides as potential antiviral agents against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV). J. Med. Chem. 37:798-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, T. S., M. Z. Luo, M. C. Liu, Y. L. Zhu, E. Gullen, G. E. Dutschman, and Y. C. Cheng. 1996. Design and synthesis of 2′,3′-dideoxy-2′,3′-didehydro-beta-L-cytidine (beta-L-d4C) and 2′,3′-dideoxy 2′,3′-didehydro-beta-L-5-fluorocytidine (beta-L-Fd4C), two exceptionally potent inhibitors of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) and potent inhibitors of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vitro. J. Med. Chem. 39:1757-1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannin, S. J., and L. B. Townsend. 1978. 2-Amino-9-B-ribofuranosylpurine-6-selone, p. 589-594. In L. B. Townsend and R. S. Tipson (ed.), Nucleic acid chemistry: improved and new synthetic procedures, methods and techniques, vol. 2. Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien, W. A. 2000. Resistance against reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Clin. Infect. Dis. 30(Suppl. 2):S185-S192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parker, W. B., and Y. C. Cheng. 1994. Mitochondrial toxicity of antiviral nucleoside analogs. J. NIH Res. 6:57-61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ray, A. S., and K. S. Anderson. 2001. Mechanistic studies to understand the inhibition of wild type and mutant HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by carbovir-triphosphate. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 20:1247-1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robins, M. J., J. S. Wilson, D. Madej, N. H. Low, F. Hanssks, and S. F. Wnuk. 1995. Nucleic acid related compounds. 88. Efficient conversions of ribonucleosides into their 2′,3′-anhydro, 2′ (and 3′)-deoxy, 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy, and 2′,3′-dideoxynucleoside analogues. J. Org. Chem. 60:7902-7908.

- 23.Shi, J., J. McAtee, S. S. Wirtz, P. Tharnish, A. Juodawlkis, D. C. Liotta, and R. F. Schinazi. 1999. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 2′,3′-didehydro-2′,3′-dideoxy-5-fluorocytidine (D4FC) analogues: discovery of carbocyclic nucleoside triphosphates with potent inhibitory activity against HIV-1 reverse transcriptase. J. Med. Chem. 42:859-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slater, T. F., B. Sawyer, and U. Strauli. 1963. Studies on succinate-tetrazolium reductase. III. Points of coupling of four tetrazolium salts. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 77:383-393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaccaro, J. A., K. M. Parnell, S. A. Terezakis, and K. S. Anderson. 1999. Mechanism of inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase by d4TTP: an equivalent incorporation efficiency relative to the natural substrate dTTP. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:217-221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vince, R., M. Hua, J. Brownell, S. M. Daluge, F. C. Lee, W. M. Shannon, G. C. Lavelle, J. Qualls, O. S. Weislow, R. Kiser, P. G. Canonico, R. H. Schultz, V. L. Narayanan, J. G. Mayo, R. H. Shoemaker, and M. R. Boyd. 1988. Potent and selective activity of a new carbocyclic nucleoside analog (carbovir: NSC 614846) against human immunodeficiency virus in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 156:1046-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]