Abstract

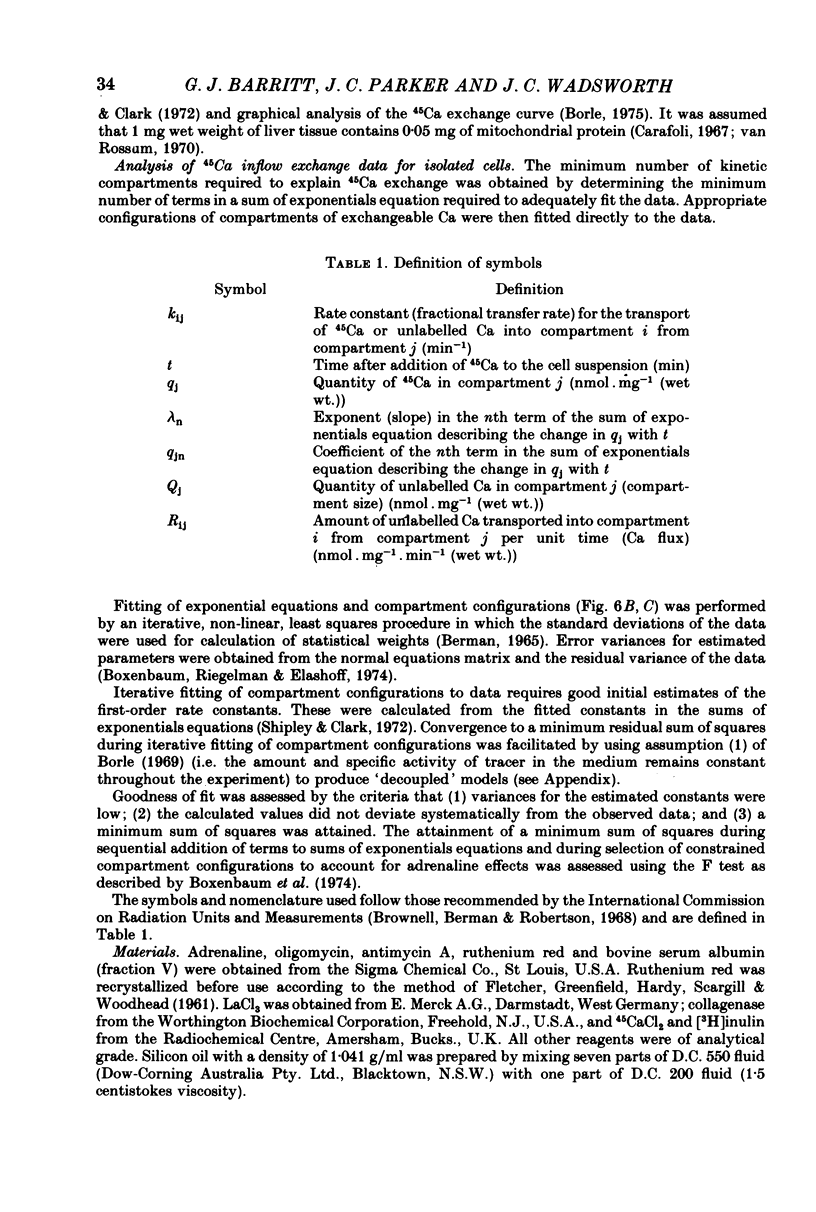

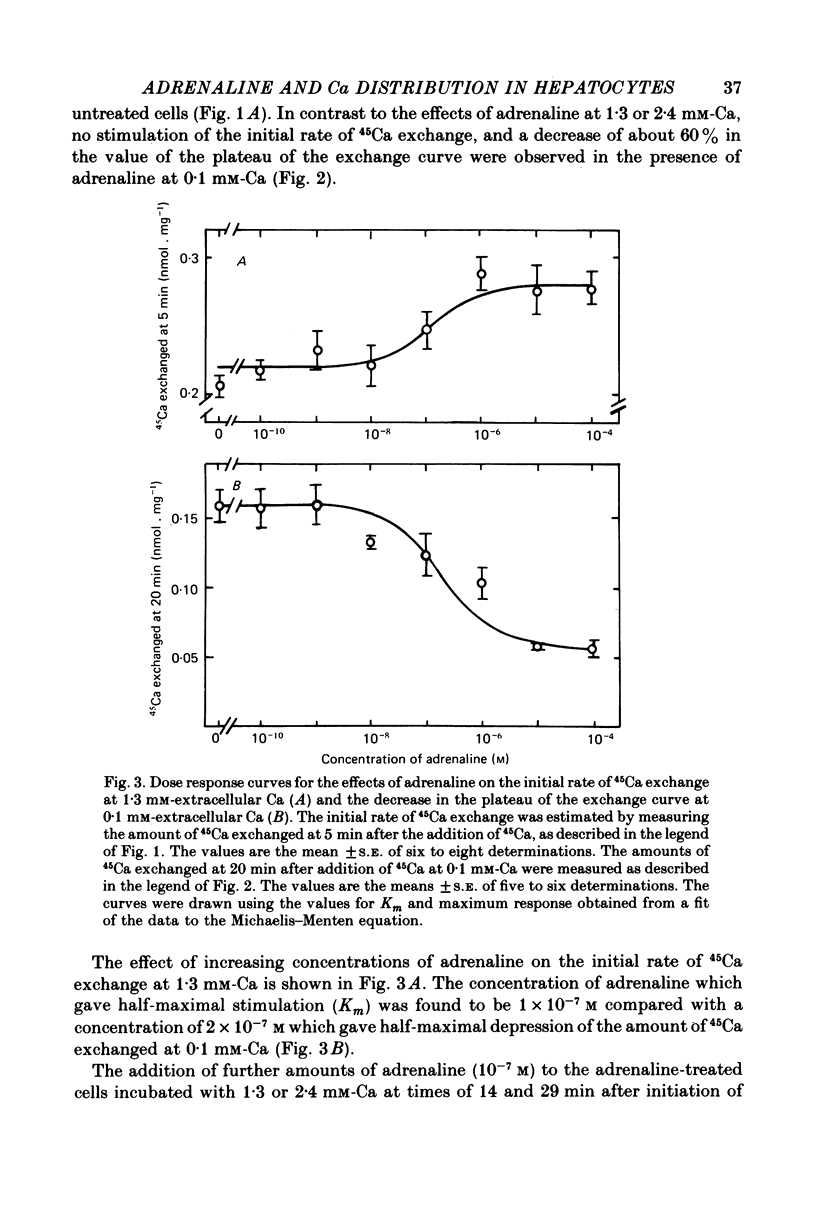

1. The effects of adrenaline on Ca distribution in isolated rat liver parenchymal cells were studied using a 45Ca exchange technique under steady-state conditions with respect to the net movement of Ca. 45Ca was initially introduced into the extracellular medium. The amount of cellular 45Ca was determined after separation of the cells from the medium by centrifugation through a solution which contained LaCl3 (to displace 45Ca bound to sites on the outside of the cell membrane) and silicon oil. At 1·3 and 2·4 mm-extracellular Ca, a stimulation of the initial rate of 45Ca exchange was observed in the presence of 10-7 m-adrenaline (or 10-6 m-phenylephrine) with a 7% decrease, and no change, respectively, in the plateau of the exchange curve. The same degree of stimulation was observed when 45Ca was added at 1, 15, 30 or 45 min after the adrenaline.

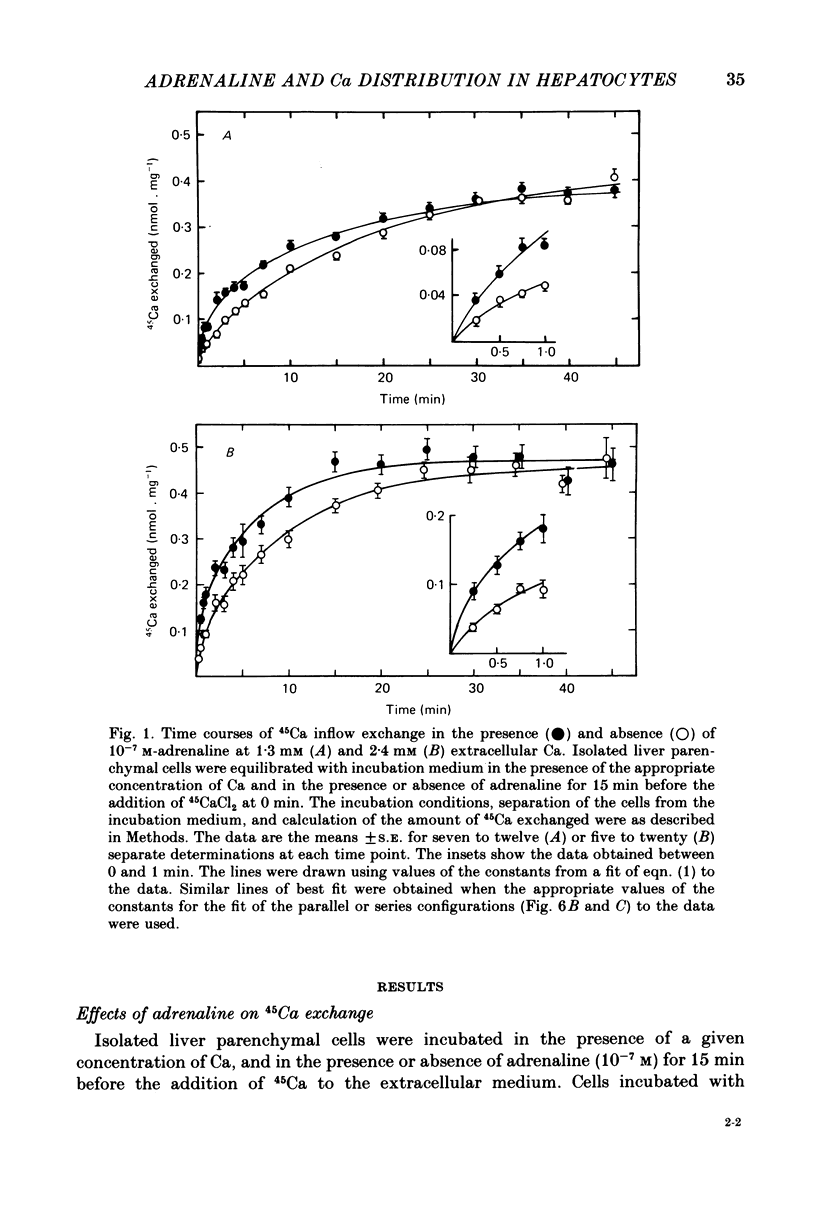

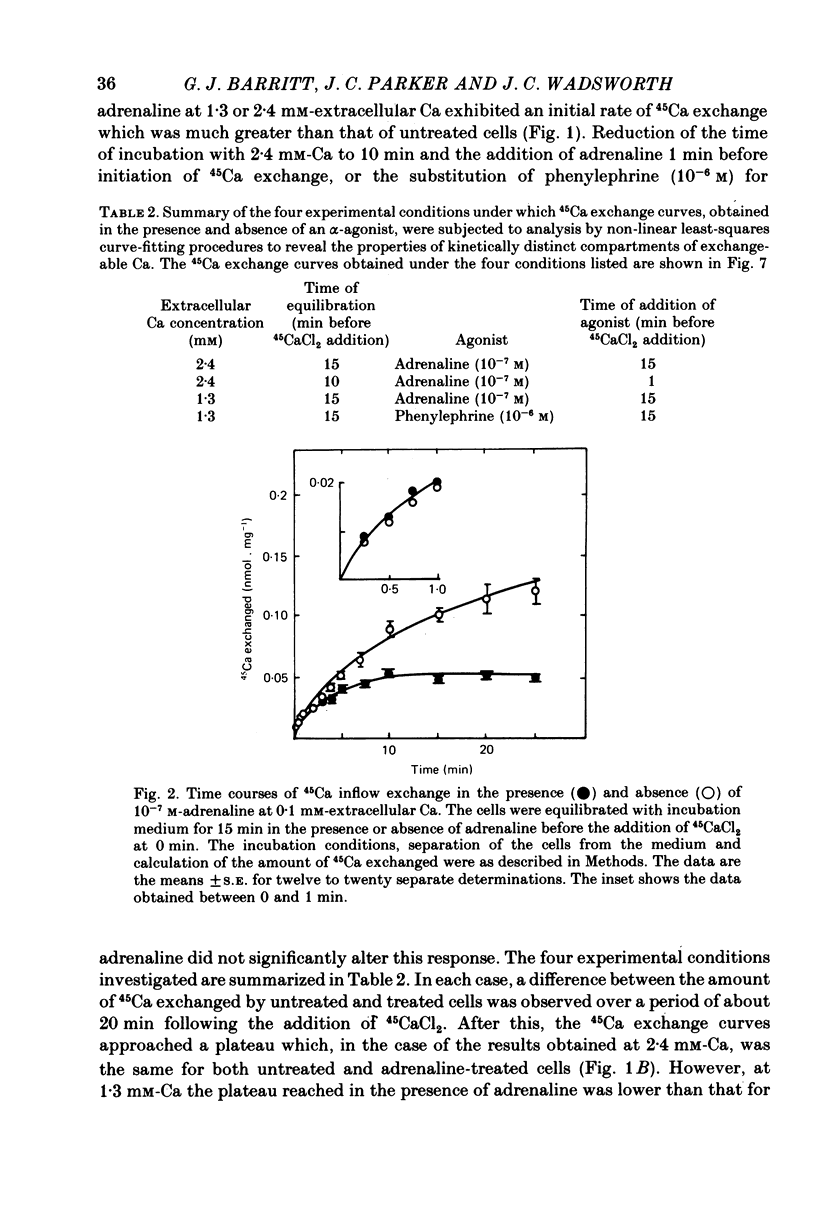

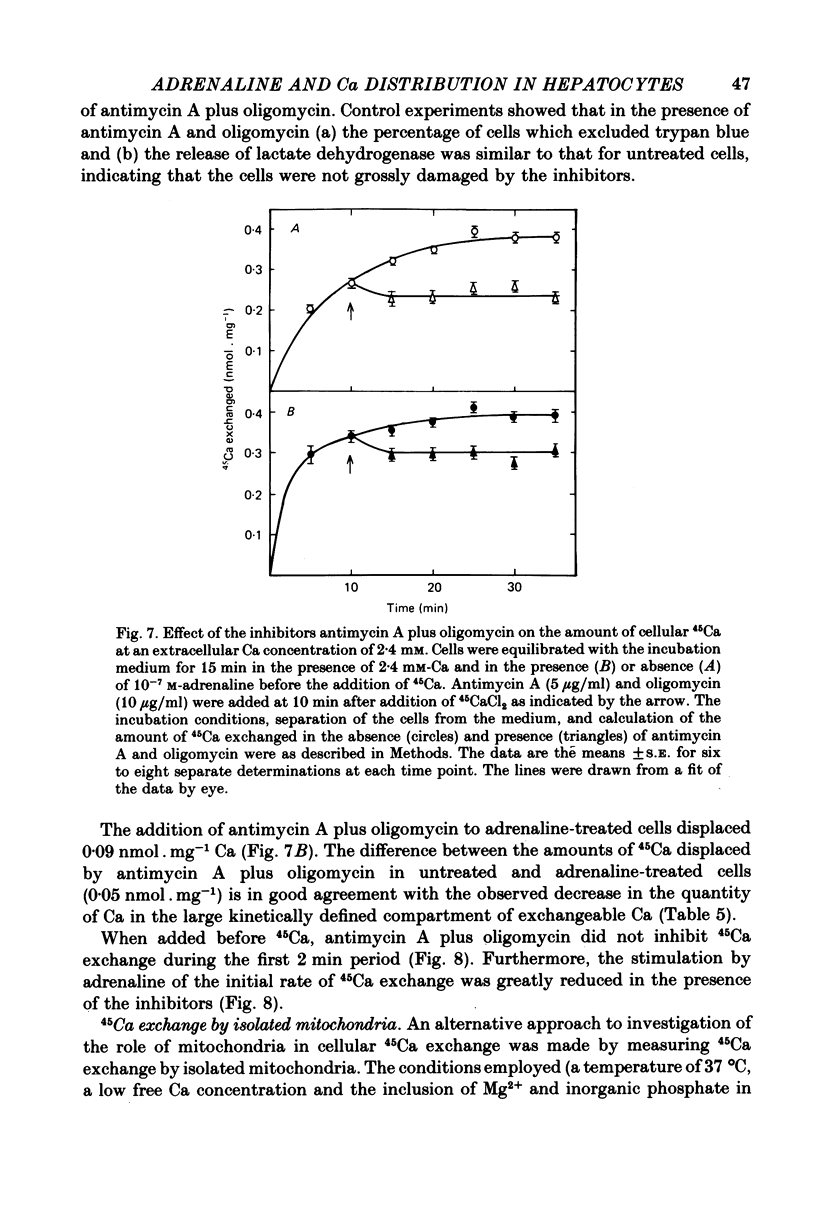

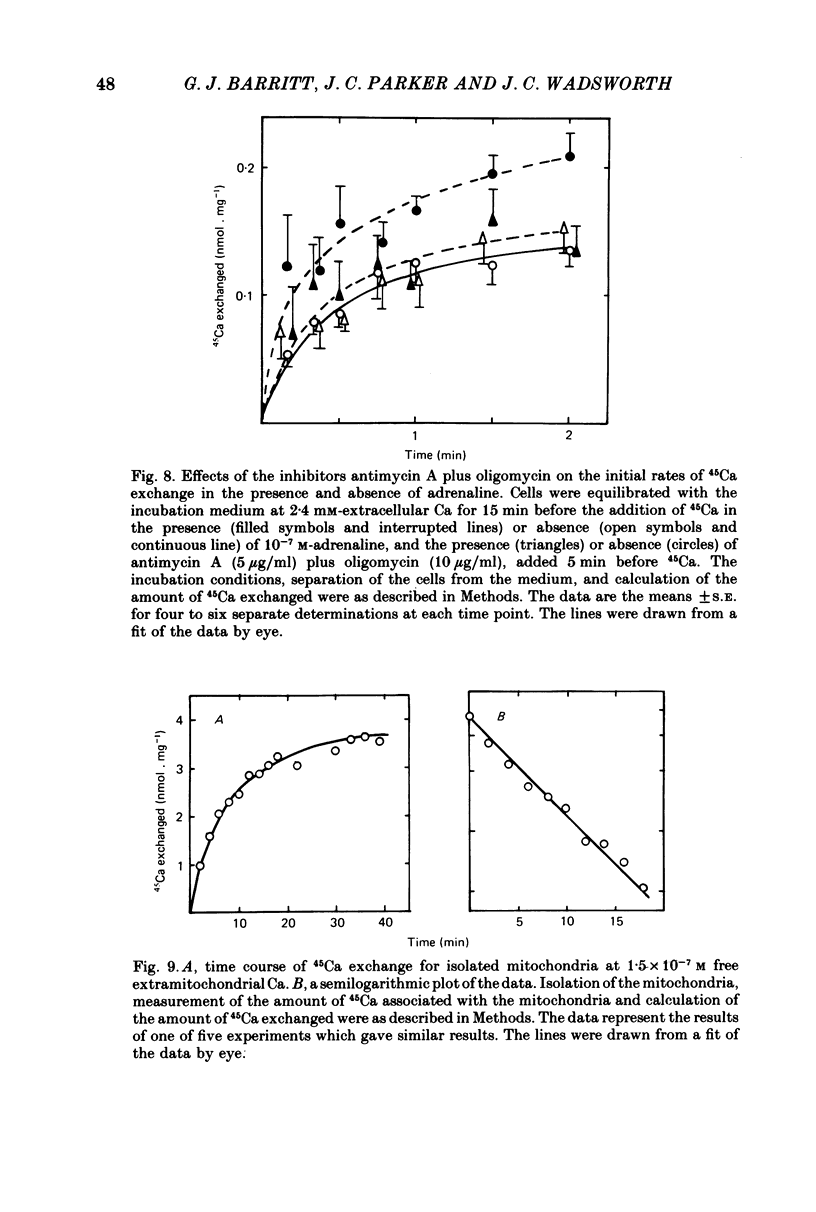

2. No stimulation of the initial rate of exchange was observed at 0·1 mm-extracellular Ca, or at 2·4 mm-extracellular Ca in the presence of antimycin A and oligomycin. At 0·1 mm-Ca, a 60% decrease in the plateau of the exchange curve was observed in the presence of adrenaline. The concentration of adrenaline (10-7 m) which caused half-maximal stimulation of the initial rate of 45Ca exchange at 1·3 mm-Ca was similar to that (2 × 10-7 m) which caused half-maximal decrease in the plateau at 0·1 mm-Ca.

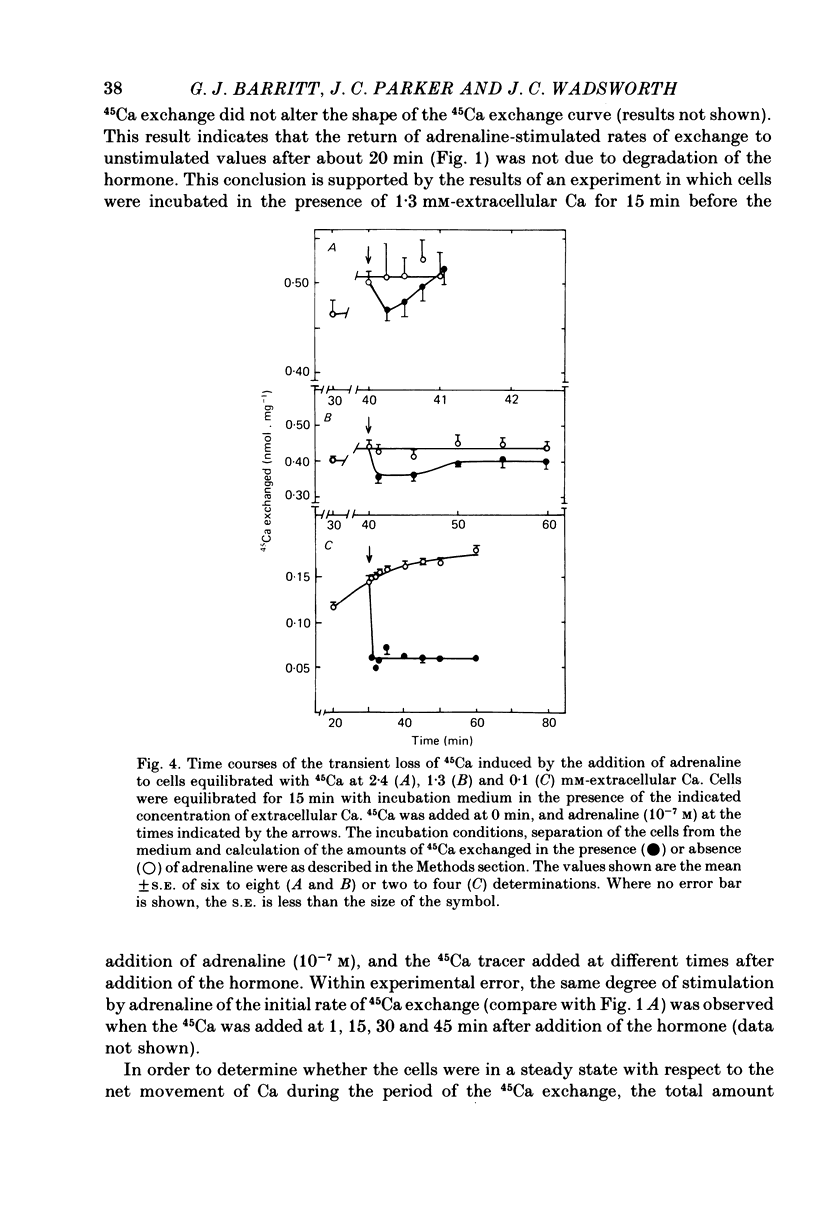

3. The addition of adrenaline to cells equilibrated with 45Ca at either 2·4 or 1·3 mm-Ca caused a transient loss of 45Ca followed by a return to a new steady state after 1 or 10 min, respectively. A loss of 45Ca was also observed at 0·1 mm-Ca, but the 45Ca content of the cells remained maximally depressed for at least 30 min.

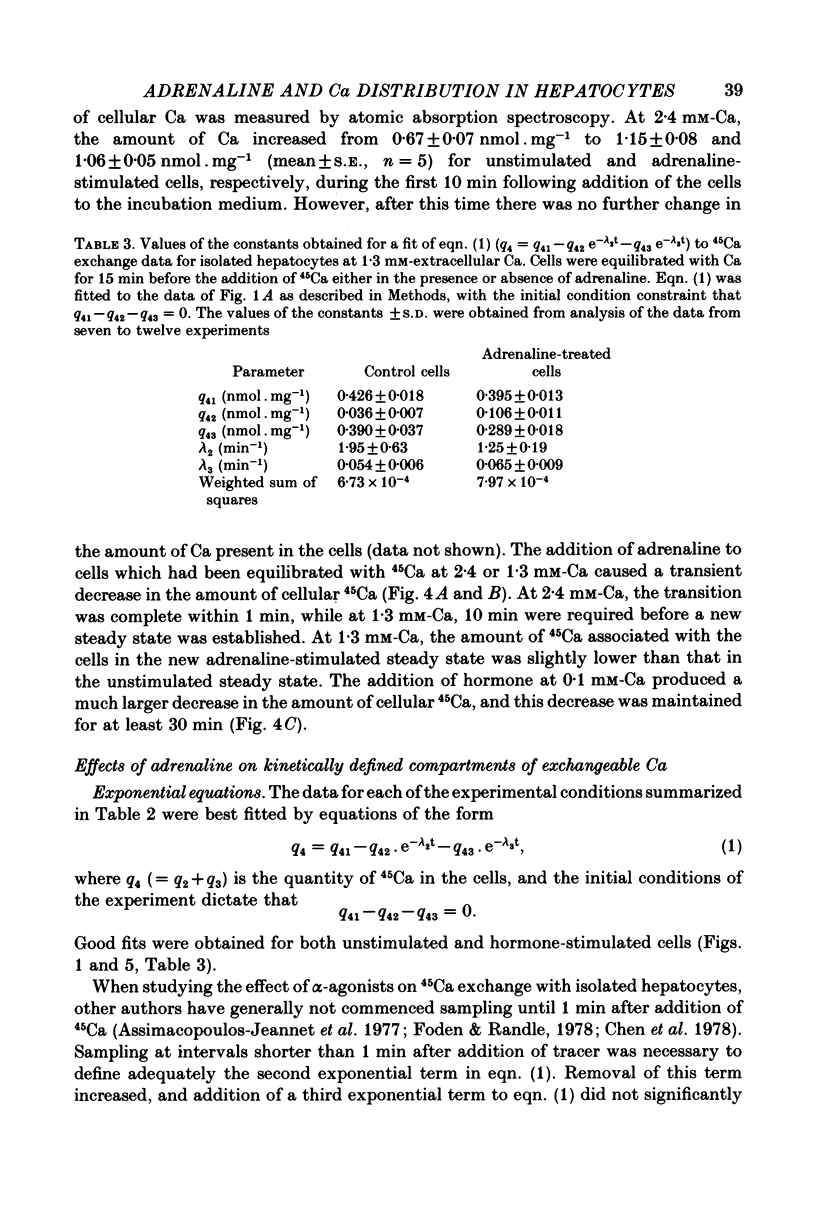

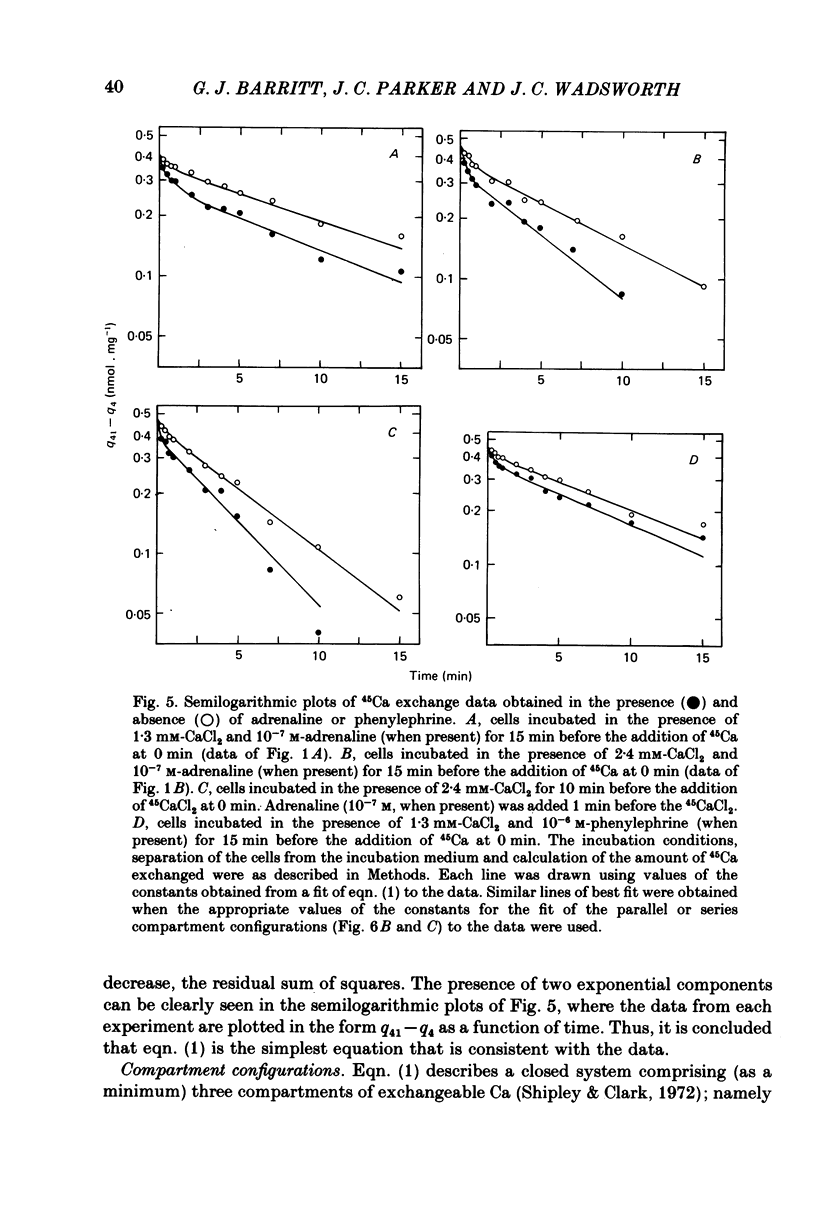

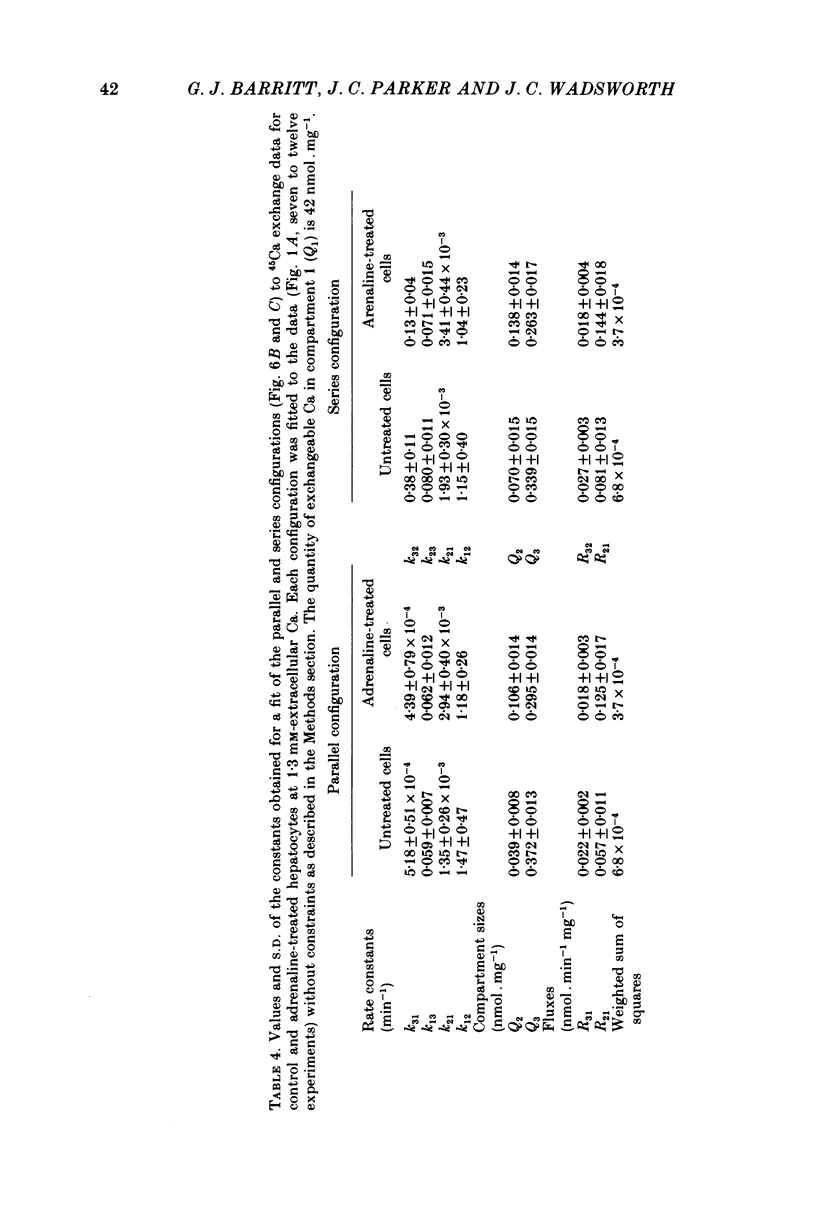

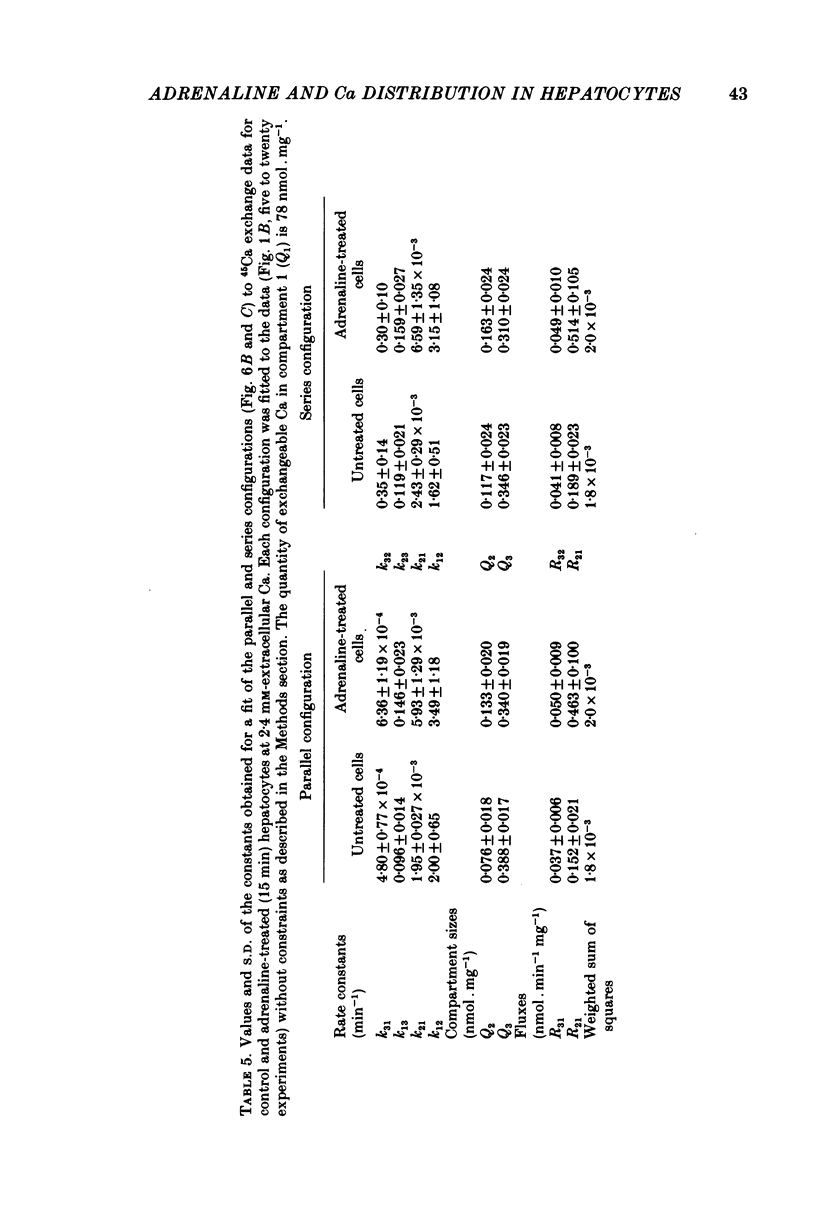

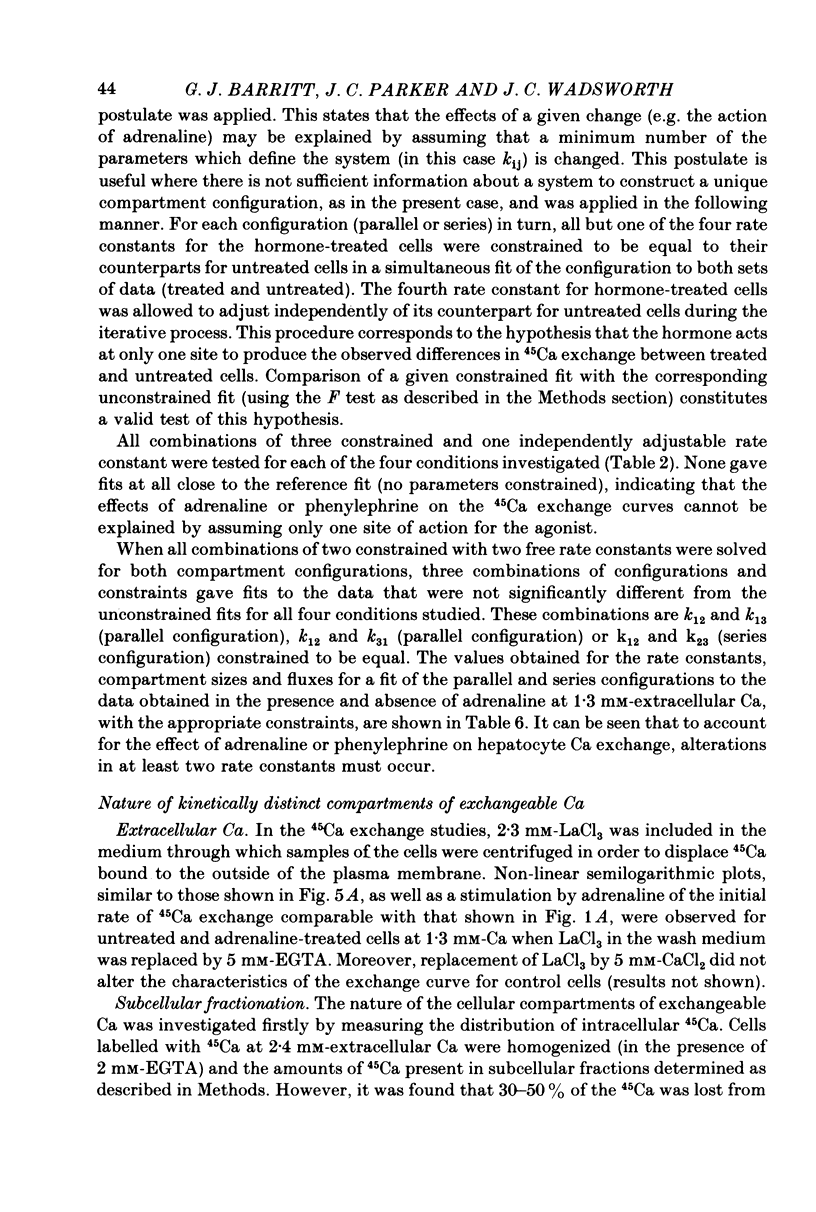

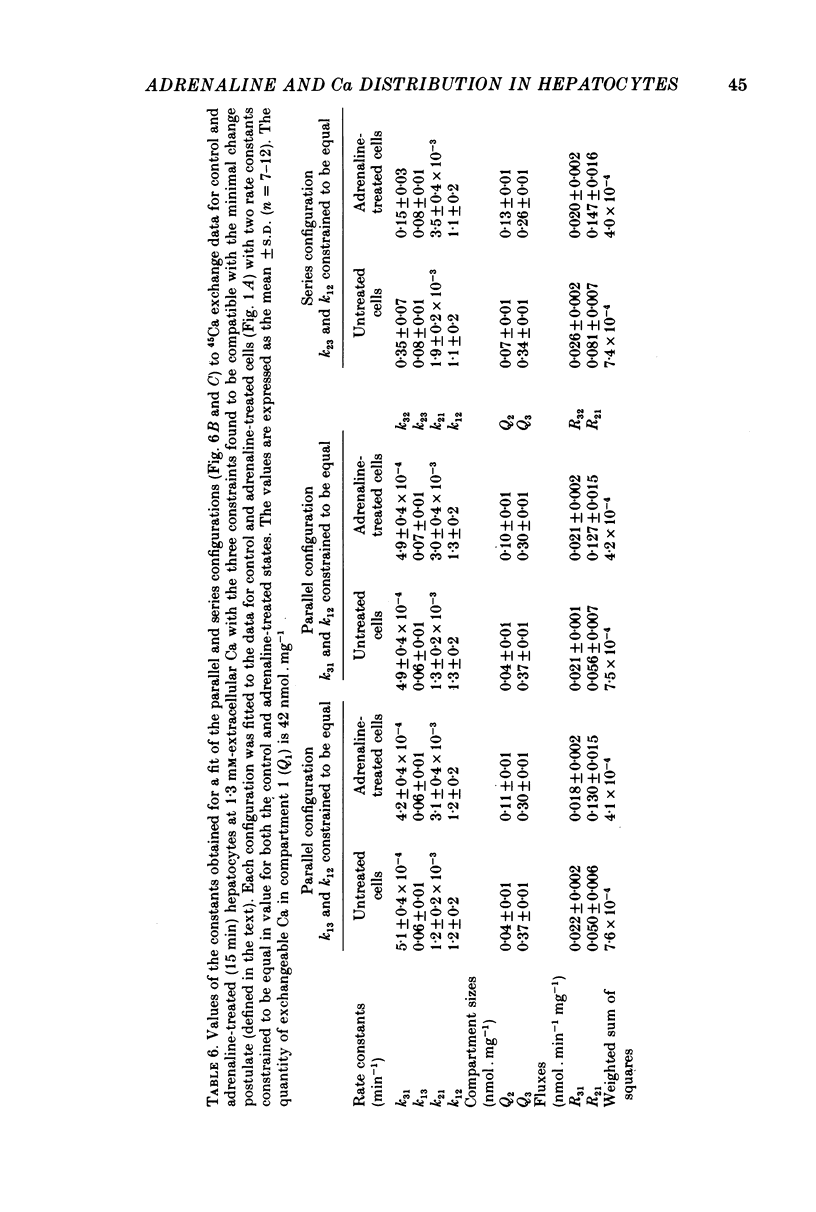

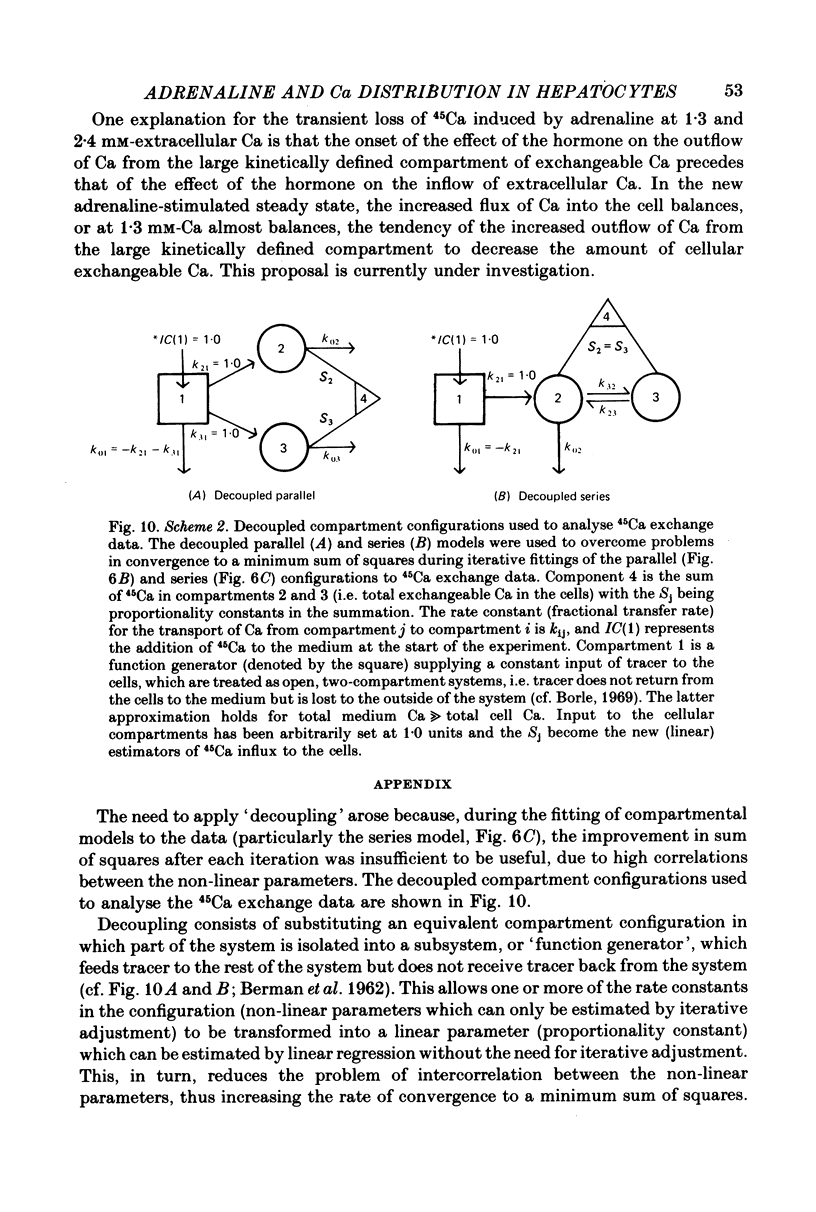

4. A non-linear least-squares iterative curve-fitting technique was used to demonstrate that (a) an equation which includes two exponential terms and (b) a parallel or series arrangement of three compartments of exchangeable Ca (the medium and two compartments associated with the cell) are consistent with each set of data obtained at 1·3 or 2·4 mm-Ca in the presence or absence of adrenaline (or phenylephrine). At 1·3 mm-Ca, the quantities of exchangeable Ca in the two kinetically defined cellular compartments were 0·04-0·07 and 0·34-0·37 nmol per mg wet weight with rate constants for Ca outflow of 1·2-1·5 and 0·06-0·08 min-1, respectively.

5. Analysis of the changes induced by adrenaline or phenylephrine showed that at 1·3 and 2·4 mm-extracellular Ca these agents caused a 75-150% increase in the quantity of exchangeable Ca in the small kinetically defined compartment and a 20% decrease in the quantity of exchangeable Ca in the large kinetically defined compartment. These changes were mediated by an 80-160% increase in the rate constant for the inflow of Ca from the medium to the small kinetically defined compartment, and either a 20-60% decrease in the rate constant for inflow to, or a 20% increase in the rate constant for outflow from, the large compartment.

6. Replacement of the LaCl3 in the solution used to separate the cells from the incubation medium with either 5 mm-EGTA or 5 mm-CaCl2 did not alter the kinetics of 45Ca exchange or the stimulation by adrenaline. This, together with the observation that at 1·3 mm-extracellular Ca, adrenaline increases the initial rate of exchange in the absence, but not in the presence, of antimycin A plus oligomycin, indicates that both cellular compartments of exchangeable Ca are intracellular.

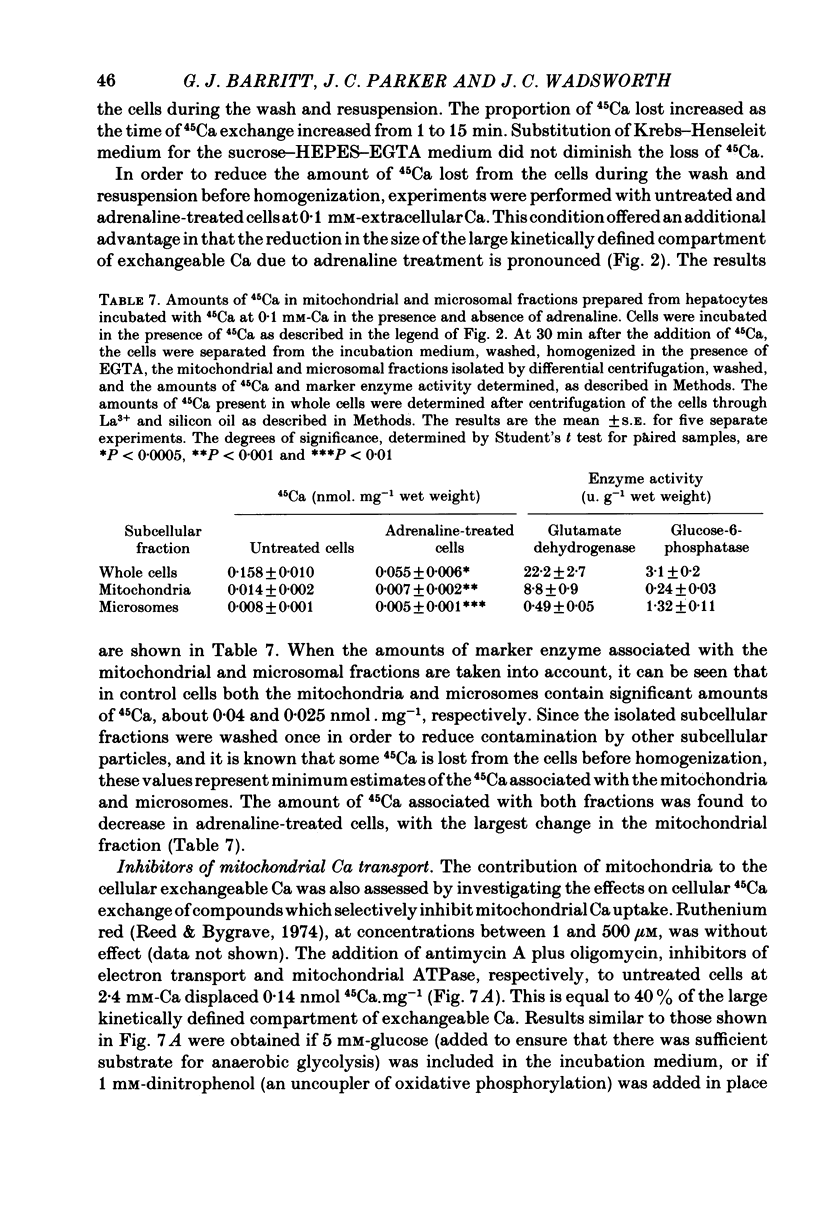

7. The addition of antimycin A plus oligomycin to cells equilibrated with 45Ca at 2·4 mm-extracellular Ca in the presence or absence of adrenaline displaced 0·09 and 0·14 nmol 45Ca. mg-1, respectively.

8. Subcellular fractionation of cells equilibrated with 45Ca at 0·1 mm-extracellular Ca revealed that the mitochondria and microsomes contained significant amounts of 45Ca. The amounts of 45Ca in these fractions decreased by 50 and 40%, respectively, in the presence of adrenaline.

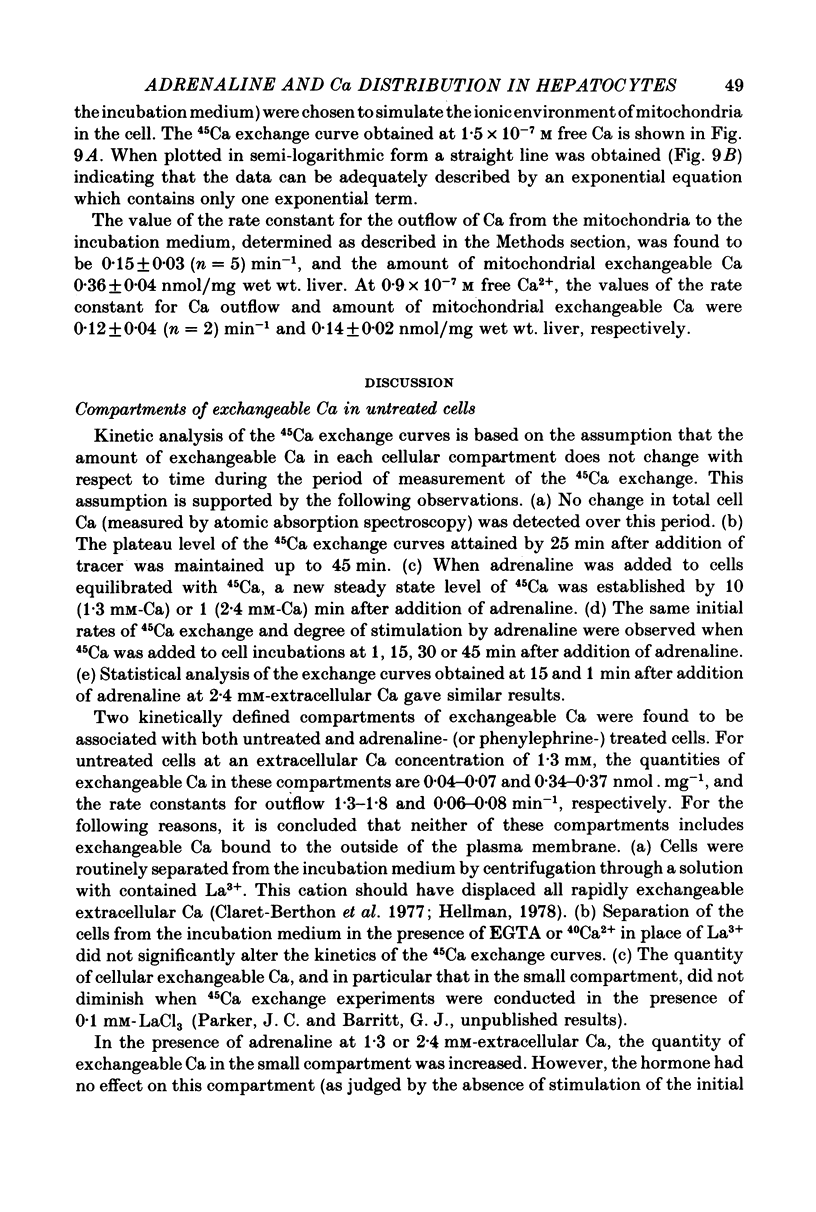

9. In 45Ca exchange experiments conducted with isolated mitochondria at 37 °C at 1·5 × 10-7 m and 0·9 × 10-7 m free Ca in the presence of 2 mm-Mg2+, one kinetically defined compartment of exchangeable mitochondrial Ca was detected. The rate constants for Ca outflow were found to be 0·15±0·03 and 0·12±0·04 min-1, respectively, in reasonable agreement with the value obtained for the rate constant for the outflow of Ca from the large kinetically defined compartment of exchangeable Ca observed in cells.

10. It is concluded that adrenaline has two effects on Ca movement in the liver cell. These are to cause a loss of Ca from an intracellular compartment, which includes the mitochondria and microsomes, and to increase the transport of Ca from the extracellular medium to an intracellular site. This results in an increase in the amount of Ca in a small intracellular compartment which may represent cytoplasmic Ca, or Ca bound to sites on the inside of the plasma membrane.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F. D., Blackmore P. F., Exton J. H. Studies on alpha-adrenergic activation of hepatic glucose output. Studies on role of calcium in alpha-adrenergic activation of phosphorylase. J Biol Chem. 1977 Apr 25;252(8):2662–2669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERMAN M., WEISS M. F., SHAHN E. Some formal approaches to the analysis of kinetic data in terms of linear compartmental systems. Biophys J. 1962 May;2:289–316. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(62)86856-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock D. F., Chen J. L., Yip B. P., Lardy H. A. Evidence for mitochondrial localization of the hormone-responsive pool of Ca2+ in isolated hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1979 Sep 10;254(17):8117–8120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks B. E., Brown C., Burgess G. M., Burnstock G., Claret M., Cocks T. M., Jenkinson D. H. Apamin blocks certain neurotransmitter-induced increases in potassium permeability. Nature. 1979 Nov 22;282(5737):415–417. doi: 10.1038/282415a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman M. A postulate to aid in model building. J Theor Biol. 1963 May;4(3):229–236. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(63)90001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M. N., Friend D. S. High-yield preparation of isolated rat liver parenchymal cells: a biochemical and fine structural study. J Cell Biol. 1969 Dec;43(3):506–520. doi: 10.1083/jcb.43.3.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore P. F., Brumley F. T., Marks J. L., Exton J. H. Studies on alpha-adrenergic activation of hepatic glucose output. Relationship between alpha-adrenergic stimulation of calcium efflux and activation of phosphorylase in isolated rat liver parenchymal cells. J Biol Chem. 1978 Jul 25;253(14):4851–4858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore P. F., Dehaye J. P., Exton J. H. Studies on alpha-adrenergic activation of hepatic glucose output. The role of mitochondrial calcium release in alpha-adrenergic activation of phosphorylase in perfused rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1979 Aug 10;254(15):6945–6950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore P. F., Dehaye J. P., Strickland W. G., Exton J. H. alpha-Adrenergic mobilization of hepatic mitochondrial calcium. FEBS Lett. 1979 Apr 1;100(1):117–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(79)81144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B. Kinetic analyses of calcium movements in HeLa cell cultures. I. Calcium influx. J Gen Physiol. 1969 Jan;53(1):43–56. doi: 10.1085/jgp.53.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B. Methods for assessing hormone effects on calcium fluxes in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1975;39:513–573. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(75)39046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borle A. B., Uchikawa T. Effects of adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate, dibutyryl adenosine 3',5'-monophosphate, aminophylline, and imidazole on renal cellular calcium metabolism. Endocrinology. 1979 Jan;104(1):122–129. doi: 10.1210/endo-104-1-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxenbaum H. G., Riegelman S., Elashoff R. M. Statistical estimations in pharmacokinetics. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1974 Apr;2(2):123–148. doi: 10.1007/BF01061504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell G. L., Berman M., Robertson J. S. Nomenclature for tracer kinetics. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1968 Mar;19(3):249–262. doi: 10.1016/0020-708x(68)90022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. In vivo effect of uncoupling agents on the incorporation of calcium and strontium into mitochondria and other subcellular fractions of rat liver. J Gen Physiol. 1967 Aug;50(7):1849–1864. doi: 10.1085/jgp.50.7.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. L., Babcock D. F., Lardy H. A. Norepinephrine, vasopressin, glucagon, and A23187 induce efflux of calcium from an exchangeable pool in isolated rat hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978 May;75(5):2234–2238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.5.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claret-Berthon B., Claret M., Mazet J. L. Fluxes and distribution of calcium in rat liver cells: kinetic analysis and identification of pools. J Physiol. 1977 Nov;272(3):529–552. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubinsky W. P., Cockrell R. S. Ca2+ transport across plasma and mitochondrial membranes of isolated hepatocytes. FEBS Lett. 1975 Nov 1;59(1):39–43. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Exton J. H., Assimacopoulos-Jeannet F. D., Blackmore P. F., Cherrington A. D., Chan T. M. Mechanisms of catecholamine actions on liver carbohydrate metabolism. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1978;9:441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foden S., Randle P. J. Calcium metabolism in rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1978 Mar 15;170(3):615–625. doi: 10.1042/bj1700615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foldes M., Barritt G. J. Regulation by calcium ions of pyruvate carboxylation, pyruvate transport, and adenine nucleotide transport in isolated rat liver mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1977 Aug 10;252(15):5372–5380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson P. E. Renewing the search for calcium pumps. Nature. 1978 Aug 3;274(5670):421–422. doi: 10.1038/274421a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopgood M. F., Clark M. G., Ballard F. J. Inhibition of protein degradation in isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochem J. 1977 May 15;164(2):399–407. doi: 10.1042/bj1640399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes B. P., Barritt G. J. Effects of glucagon and N6O2'-dibutyryladenosine 3':5'-cyclic monophosphate on calcium transport in isolated rat liver mitochondria. Biochem J. 1978 Oct 15;176(1):295–304. doi: 10.1042/bj1760295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keppens S., Vandenheede J. R., De Wulf H. On the role of calcium as second messenger in liver for the hormonally induced activation of glycogen phosphorylase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977 Feb 28;496(2):448–457. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(77)90327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaNoue K. F., Bryla J., Williamson J. R. Feedback interactions in the control of citric acid cycle activity in rat heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1972 Feb 10;247(3):667–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. R., Denton R. M. The intracellular localization of enzymes in white-adipose-tissue fat-cells and permeability properties of fat-cell mitochondria. Transfer of acetyl units and reducing power between mitochondria and cytoplasm. Biochem J. 1970 May;117(5):861–877. doi: 10.1042/bj1170861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin D. D., Sayce I. G. Computer calculation of equilibrium concentrations in mixtures of metal ions and complexing species. Talanta. 1967 Jul;14(7):833–842. doi: 10.1016/0039-9140(67)80105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed K. C., Bygrave F. L. Accumulation of lanthanum by rat liver mitochondria. Biochem J. 1974 Feb;138(2):239–252. doi: 10.1042/bj1380239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed K. C., Bygrave F. L. Methodology for in vitro studies of Ca-2+ transport. Anal Biochem. 1975 Jul;67(1):44–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90270-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter H. Exchange of calcium ions in the mammalian myocardium. Mechanisms and physiological significance. Circ Res. 1974 May;34(5):599–605. doi: 10.1161/01.res.34.5.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatzmann H. J., Bürgin H. Calcium in human red blood cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1978 Apr 28;307:125–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb41939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer R. K., Borle A. B. Effect of pH on the calcium metabolism of isolated rat kidney cells. J Membr Biol. 1979 Aug;48(4):325–341. doi: 10.1007/BF01869444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]