Abstract

This paper concerns the Circular Dichroism (CD) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) structural studies of the quadruple helix arrangements adopted by three tailored oligodeoxyribonucleotide analogues, namely d(TGMeGGT), d(TGGMeGT) and d(TGGGMeT), where dGMe represents a 8-methyl-2′-deoxyguanosine residue. The results of this study clearly demonstrate that the effects of the incorporation of dGMe instead of a dG residue are strongly dependant upon the positioning of a single base replacement along the sequence. As such, d(TGMeGGT), d(TGGMeGT) have been found to form 4-fold symmetric quadruplexes with all strands parallel and equivalent to each other, each more stable than their natural counterpart. NMR experiments clearly indicate that [d(TGMeGGT)]4 possesses a GMe-tetrad with all dGMe residues in a syn-glycosidic conformation while an anti-arrangement is apparent for the four dGMe of [d(TGGMeGT)]4. As the two complexes show a quite different CD behaviour, a possible relationship between the presence of residues adopting syn-glycosidic conformations and CD profiles is briefly discussed. As far as d(TGGGMeT) is concerned, NMR data indicate that at 25°C it exists primarily as a single-strand conformation in equilibrium with minor amounts of a quadruplex structure.

INTRODUCTION

G-quadruplex (or tetraplex) structures are an attractive topic of several research areas (1) ranging from structural chemistry to molecular biology and, recently, to analytical chemistry (2). Guanine-rich sequences potentially able to form G-quadruplex structures frequently occur in the human genome (3). As such, they have been found in a number of biologically important DNA regions such as promoter regions (4), centromeres and telomeres (5). Furthermore, they form the core of several aptamers, namely oligodeoxyribonucleotides (ODNs) obtained from SELEX technology (6,7), provided with impressive affinity and selectivity towards a given target molecule, and therefore are considered to be very promising pharmaceutical agents (8). G-quadruplexes are extremely polymorphic particularly with regard to three mutually related aspects: the relative orientation of the strands, the syn/anti-glycosidic torsion angle of the guanine residues, and the structure of the loops connecting the strands (where present). The nature of the buffer cations also seems to play a key role in the selection amongst the various structures that an ODN may adopt (9). Recent studies of quadruplex structures have shown that ODNs containing one, two or four G-tracts can form tetramolecular, bimolecular or monomolecular G-quadruplexes, respectively. In particular, in tetramolecular G-quadruplexes examined thus far, strands are found to be parallel and guanine bases are all anti (1) thereby indicating that this structure was preferred when looping constraints were absent.

However, in a recent paper (10), some of us described a combined Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), molecular mechanic and dynamic calculations and Circular Dichroism (CD) spectroscopy characterization of three quadruplexes [d(TGBrGGT)]4, [d(TGGBrGT)]4 and [d(TGGGBrT)]4, where a 8-bromo-2′-deoxyguanosine (dGBr) residue was introduced into the different positions of the sequence 5′-d(TGGGT)-3′. All three complexes were found to form parallel stranded quadruplexes with all guanines-including dGBr residues-involved in hydrogen-bonded tetrads. Furthermore, based upon molecular modelling simulations and literature data, all dGBr residues were assumed to adopt syn-glycosidic conformations. Interestingly, the introduction of a dGBr residue in G2, G3 and G4 positions provided both different thermal stabilities and CD spectra. In particular, [d(TGBrGGT)]4 and [d(TGGBrGT)]4 showed higher melting temperatures than their natural counterpart, whereas [d(TGGGBrT)]4 is less stable than the parent ODN. As far as CD experiments are concerned, it is interesting to note that [d(TGBrGGT)]4, despite NMR observations, shows a spectral behaviour that is typical for anti-parallel quadruplexes. These results could afford an unprecedented view about the relationship amongst the relative orientation of the strands, the glycosidic conformation of the G bases and the CD spectra of the quadruplex structures, so that we decided to perform further investigations. However, the advantage that the 8-bromo-dG phosphoramidite derivative is commercially available, is countered by the fact that a dGBr residue cannot provide direct proof for the syn-glycosidic conformation of GBr bases (due to the lack of the proton in 8-position potentially involved in diagnostic NOEs with the H1′ sugar proton).

With this in mind, we turned our attention to another class of ODN analogues, namely those containing 8-methyl-deoxyguanosine residues, taking into consideration that the methyl group with a steric size comparable to that of the bromine atom is similarly inclined to promote the syn-glycosidic conformation (11) and, at the same time, may provide further structural information based on NOE contacts involving its protons.

In this paper we report the structural study based upon NMR and CD spectroscopy associated with molecular mechanic and dynamic calculations of quadruplexes Q1, Q2 and Q3 formed by oligonucleotides 5′-d(TGMeGGT)-3′ (1), 5′-d(TGGMeGT)-3′ (2) and 5′-d(TGGGMeT)-3′ (3), respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The oligonucleotides 1, 2 and 3 were synthesized on a Millipore Cyclone Plus DNA synthesizer using solid phase β-cyanoethyl phosphoramidite chemistry at 15 µmol scale. The oligomers were detached from the support and deprotected by treatment with concentrated aqueous ammonia at 55°C for 12 h. The combined filtrates and washings were concentrated under reduced pressure, redissolved in H2O and analysed and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Nucleogel SAX column (Macherey–Nagel, 1000-8/46); using buffer A: 20 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 aqueous solution (pH 7.0), containing 20% (v/v) CH3CN; buffer B: 1 M KCl, 20 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4 aqueous solution (pH 7.0), containing 20% (v/v) CH3CN; a linear gradient from 0 to 100% B for 30 min and flow rate 1 ml/min were used. The isolated oligomers had the following retention times: 1 = 18.0 min; 2 = 8.4 min and 17.0 min; 3 = 8.3 min and 16.0 min. In the case of 2 and 3, the two species at different retention times prepared under the same conditions, yielded superimposable 1H-NMR spectra. The different fractions of the same oligomer were collected and successively desalted by Sep-pak cartridges (C-18). The isolated oligomers proved to be >98% pure NMR.

NMR

NMR samples were prepared at a concentration of ∼3 mM, in 0.6 ml (H2O/D2O 9:1 v/v) buffer solution having 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0). For D2O experiments, the H2O was replaced with D2O by drying down the sample, lyophilization and redissolution in D2O alone. NMR spectra were recorded with Varian UnityINOVA 700 MHz for Q2 and, for a limitation of instrument access, Varian UnityINOVA 500 MHz for Q1. 1H chemical shifts were referenced relative to external sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS), whereas 31P chemical shifts were referenced to external phosphoric acid (H3PO4 85% v/v). 1D proton spectra of samples in H2O were recorded using pulsed-field gradient WATERGATE (12) for H2O suppression. Phase sensitive NOESY spectra (13) were recorded with mixing times of 100 and 200 ms (T = 25°C). Pulsed-field gradient WATERGATE was used for NOESY spectra in H2O. TOCSY spectra (14) with mixing times of 120 ms were recorded with D2O solutions. NOESY and TOCSY were recorded using a TPPI (15) procedure for quadrature detection. In all 2D experiments the time domain data consisted of 2048 complex points in t2 and 400–512 fids in t1 dimension. The relaxation delay was kept at 1.2 s for all experiments. The NMR data were processed on a SGI Octane workstation using FELIX 98 software (Byosym, San Diego, CA).

Structural calculations

The structure calculations were performed with the CYANA program (16) starting from 200 random conformations. Upper-limit distance constraints for both exchangeable and non-exchangeable hydrogens were classified according to their intensity in the NOESY spectra (mixing time = 100 ms) with the CALIBA tool of the program CYANA (16). The 200 and 380 upper distance restraints were calculated for Q1 and Q2, respectively, and reduced to 112 and 224 after removal of the irrelevant ones. Pseudo-atoms were introduced where needed. Hydrogen bond constraints (16 upper and 16 lower limit constraints/G-tetrad) were used: upper and lower distance limits of 2.0 and 1.7 Å for hydrogen-acceptor distance, and 3.0 and 2.7 Å for donor-acceptor distance, respectively. These constraints for H-bonds did not lead to an increase in residual constraints violation. Furthermore, in accordance with the observed 31P chemical shifts (17–19), backbone torsion angles were restricted to a range of ± 20° of the helical values of natural quadruplexes (20). According to NMR data, glycosidic torsion angles for all unmodified guanines were kept within a range of −157°/−97° (anti-conformation), whereas for dGMe residues in the structures calculated for Q1, the χ angle was kept within a range of 10°/100° (syn-conformation), while in the case of Q2 the glycosidic torsion angle for the modified guanines was also fixed in the anti-field (−167°/−67°).

The input for final CYANA structural calculations also included constraints to close the sugar rings (C4′–O4′: 1.41 Å, C4′–C1′: 2.40 Å, C5′–C4′: 2.39 Å, H4′–O4′: 2.12 Å). The dynamics run for 35 000 steps (highsteps = 7000; minsteps = 7000). The 10 structures with the lowest CYANA target functions were subject to energy minimization (with no angle constraint) by conjugate gradient methods as implemented in the program DISCOVER (Molecular Simulations, San Diego, CA), using CVFF force field. During energy minimization, interproton distances and H-bond constraints involving G-tetrads were used with a force constant of 20 and 100 kcal mol−1 Å−2, respectively. Illustrations of structures were generated with INSIGHTII program, version '98 (Biosym Technologies Inc.). All the calculations have been performed on a SGI Octane workstation.

CD

CD samples of Q1, Q2, Q3 and their natural counterpart [d(TGGGT)]4 were prepared at a concentration of 1 × 10−4 M by using the buffer solution used for NMR experiments: 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0). CD spectra of all quadruplexes and CD melting curves were registered on a Jasco 715 CD spectrophotometer in a 0.1 cm pathlength cuvette. For the CD spectra, the wavelength was varied from 220 to 320 nm at 100 nm min−1, and the spectra recorded with a response of 16 s, at 2.0 nm bandwidth and normalized by subtraction of the background scan with buffer. The temperature was kept constant at 20°C for Q1 and Q2, and at 5°C for Q3 with a thermoelectrically-controlled cell holder (Jasco PTC-348). CD melting curves were registered as a function of temperature from 20 to 90°C for Q1 and Q2, and from 5 to 80°C for Q3 at their maximum effect Cotton wavelengths. The CD data were recorded in the same buffer as that used for NMR experiments in a 0.1 cm pathlength cuvette with a scan rate of 10°C h−1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The synthesis of the suitably protected dGMe phosphoramidite monomer used for the preparation of dGMe-oligodeoxynucleotides (dGMe-ODNs) was performed following a recently proposed synthetic strategy (21). The monomer was then protected at the exocyclic amino and 5′-OH groups and activated by coupling with 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite. 1, 2 and 3 were assembled using the standard phosphoramidite chemistry of the automatized DNA synthesis. The crude oligomers were purified by HPLC and desalted. The NMR samples were prepared at a concentration of 3.0 mM in strands (0.6 ml, 90% H2O/10% D2O), having a 10 mM potassium phosphate, 70 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0) buffer.

The samples were heated for 5–10 min at 80°C and slowly cooled down (10–12 h) to room temperature. The solutions were equilibrated at least for one day at 4°C and then their 1H-NMR spectra were recorded by using pulsed-field gradient WATERGATE (12) for H2O suppression. The achievement of a completed annealing process was guaranteed by the achievement of superimposable 1H-NMR spectra on changing time. The simple appearance of 1D 1 and 2 spectra indicates that under the conditions utilized, both the modified oligomers form a mainly single, well-defined hydrogen-bonded conformation consistent with highly symmetric G-quadruplex structures containing three G-tetrads and possessing a 4-fold symmetry with all strands equivalent to each other. In fact, the 1H-NMR spectra of both 1 and 2 (500 and 700 MHz, respectively, T = 25°C) show the presence of three well-defined signals in the region 11–12 p.p.m., attributable to imino protons involved in Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds of G-quartets, and of four singlets belonging to two guanine H8 and two thymine H6 protons in the aromatic region. Furthermore, three methyl resonances of circa 1.6 p.p.m. for the two T-CH3 and 2.4 p.p.m. for the GMe-CH3 were observed for both samples.

On the other hand, the spectrum of 3 at the same temperature showed the presence of two sets of signals, each with four resonances differing in intensity in the aromatic range between 7.2 and 8.2 p.p.m., and only three low imino peaks in the region of 11–12 p.p.m. By raising the temperature up to 50°C, four out of eight signals gradually increased in intensity whereas the other four, along with the three imino peaks, progressively disappeared. Thus, at 50°C only four signals were present in the aromatic region of the 1H-NMR spectrum, while no imino peak was present. This suggests that at 50°C, 3 is exclusively present as a single-strand conformation which coexists with minor amounts (∼10%) of a quadruplex structure at 25°C. Unfortunately the quadruplex/single-strand ratio could not be increased by diminishing the temperature down to 10°C. Anyway, the quadruplex Q3, as well as Q1 and Q2, are parallel stranded with a 4-fold symmetry as indicated by the number of imino protons.

The exchange rates of the imino protons of Q1, Q2 and Q3 with solvent were qualitatively estimated by partially drying the samples in water and reconstituting them in D2O. Periodic examination of the imino proton signals shows that they slowly exchange into D2O solution compared to the NMR timescale, consistently with the high kinetic stability and low solvent accesibility of quadruplex structures (22).

As far as Q3 is concerned, the excess of single-strand prevented us from performing a resonance assignment and a structural study of the minor quadruplex species in solution. On the other hand, NOESY and TOCSY spectra of Q1 and Q2, obtained at 700 MHz for the former and at 500 MHz for the latter (T = 25°C) showed well-dispersed cross peaks and thus both exchangeable and non-exchangeable protons could be nearly completely assigned following the standard procedures (23) (Table 1). As reported for other parallel quadruplex structures (24,25), the observed NOEs among G H8 and T-H6 and their own H1′, H2′ and H2″ ribose protons and the H1′, H2′ and H2″ protons on the 5′ side suggest that both quadruplexes assume a right-handed helical winding.

Table 1.

Proton chemical shifts for Q1 (500 MHz) and Q2 (700 MHz) quadruplexes in 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0, T = 25°C)

| Base (5′ to 3′) | H8/H6 | H1′ | H2′/H2″ | H3′ | H4′ | H5′/H5″ | H2/Me | NH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | ||||||||

| T | 7.42 | 6.05 | 2.11–2.47 | 4.81 | 4.43 | 3.93 | 1.61 | |

| GMe | 5.95 | 2.94 | 4.95 | 4.35 | 3.84 | 2.29 | 12.03 | |

| G | 8.16 | 6.09 | 2.60–2.79 | 3.00 | 4.46 | 4.37 | 11.60 | |

| G | 7.64 | 6.27 | 2.50–2.65 | 4.85 | 4.49 | 4.18 | 10.93 | |

| T | 7.36 | 6.06 | 2.16 | 4.46 | 4.46 | 4.05–4.19 | 1.60 | |

| Q2 | ||||||||

| T | 7.36 | 5.92 | 2.10/2.29 | 4.67 | 4.03 | 3.67/3.63 | 1.41 | |

| G | 8.12 | 6.18 | 2.91/3.06 | 5.02 | 4.41 | 3.93/4.06 | 11.82 | |

| GMe | 6.08 | 2.58/2.88 | 5.09 | 4.46 | 4.22 | 2.38 | 11.68 | |

| G | 7.81 | 6.17 | 2.51/2.63 | 5.00 | 4.47 | 4.25/4.03 | 11.06 | |

| T | 7.28 | 6.04 | 2.14 | 4.46 | 4.23 | 4.02/4.06 | 1.68 | |

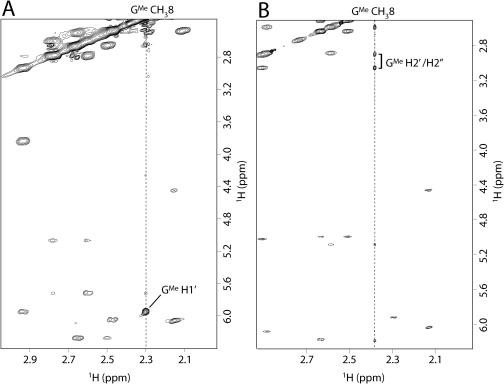

As for the glycosidic torsion angles in Q2, the presence of very weak NOEs between G H8/GMe CH38 and H1′ and of the strong NOEs observed between G H8/GMe CH38 and ribose H2′ indicates that all residues (including the dGMe bases) possess an anti-glycosidic conformation (Figure 1B). With regards to the quadruplex Q1, all the canonical guanine and thymine residues are in an anti-conformation with the exception of the modified nucleotides (dGMe) which adopt a syn-glycosidic conformation showing intense NOEs between methyl group in 8-position and H1′ sugar proton and weaker crosspeaks between methyl and H2′ (Figure 1A). Because of the syn dGMe nucleosides, the protons of methyl group in 8-position are >6 Å away from the sugar protons on the neighbouring 5′ nt (26) and the normal sequential connectivities path is broken at 5′-TGMe-3′ level.

Figure 1.

Expanded NOESY spectra (500 MHz for Q1 and 700 MHz for Q2, T= 25°C; strands concentrations ∼3 mM solution: 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl and 0.2 mM EDTA (pH 7.0) in D2O, total volume = 0.6 ml; mixing time = 200 ms) correlating sugar GMe CH38 protons (depicted by vertical dashed lines) and H1′ and H1′/H2″ for Q1 (A) and Q2 (B), respectively.

Furthermore, in the NOESY spectrum of Q2 recorded in H2O, we observed sequential imino–imino NOEs arising from intra-strand contacts between the GMe-tetrad and that below it. Moreover, interstrand NOEs between the methyl group of a dGMe residue and the NH proton of the modified base on the adjacent strand, compared to interstrand NOE contacts observed between H8 and NH protons of the unmodified tetrad below, suggest that dGMe residues are not randomly oriented and in mutual close proximity, as they are arranged in a symmetrical fashion and are stacked on the plane of the G-tetrads.

2D NOESY spectra of Q1 and Q2 (mixing time = 100 ms) show well-dispersed crosspeaks, allowing the quantification of the experimental NMR data. In order to determine the three-dimensional structure of the complexes Q1 and Q2, the Overhauser effect intensities were converted into distance restraints by the tool CALIBA of the program CYANA (16). Pseudo-atoms were introduced where needed for both structures. Furthermore, according NH deuterium exchange study, hydrogen bond distance restraints about three layers of G-tetrad were also incorporated during the refinements. Further 48 supplementary distance restraints (HN1-O6, N1-O6, HN2-N7 and N2-N7) for 24 H-bonds corresponding to the three G-quartets were used.

200 upper distance restraints for Q1 and 380 for Q2 were derived from NOE peaks analysis and reduced to 112 and 224, respectively, upon removal of the irrelevant ones. Constraints for the backbone torsion angles were deduced from the 31P chemical shifts and the analysis of the H1′/H2′ coupling constants. The proton-decoupled phosphorous spectra of both Q1 and Q2 in D2O at 25°C show that all 31P signals are clustered within the −0.8 and −2.2 p.p.m. region which is characteristic of unperturbed backbone phosphates of parallel stranded quadruplexes (17–19). Moreover, Primitive Exclusive COSY (PE-COSY) spectra analysis indicates that H1′/H2′ coupling constants are reasonably large. This suggests that the sugar geometries are predominantly S-type and consequently, the strand structure may be taken to be similar to B-form (as in parallel DNA quadruplexes) rather than A-form DNA. Therefore, backbone torsion angles were restricted within a range of ±20° of helical values of the natural quadruplex [d(TGGGGT)]4 except for dGMe residues. For these a range of ±40° was used in order to allow them a wider conformational flexibility.

The structure determinations for Q1 and Q2 were performed using restrained distance geometry calculations by the program CYANA (16). In both cases the calculations started with 200 randomised conformers and the analysis was focalised on the 10 structures with the lowest CYANA target functions resulting from van der Waals and restraint violations. As a result, these structures were subject to restrained energy minimization (no angle constraints were used) using the CVFF forcefield as implemented in the program Discover (Molecular Simulations, San Diego, CA).

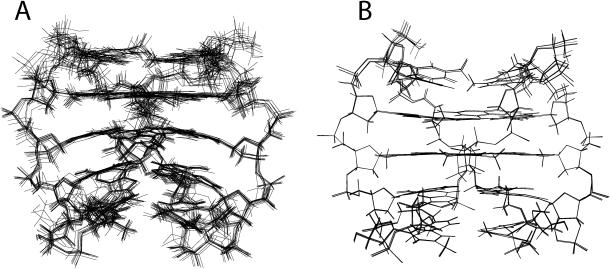

In particular, average RMSD values of 0.97 ± 0.40 and 0.94 ± 0.45 for the backbone and all heavy atoms, respectively, were obtained from the superimposition of the 10 minimized structures obtained for Q1, while RMSD values of 0.17 ± 0.11 and 0.14 ± 0.09 were calculated for Q2 showing that the NOE restraints are largely satisfactory for both complexes (Figure 2). It is interesting to note that the RMSD values calculated for Q2 are inferior to those for Q1. In fact, the structures of Q2 have been calculated using almost double the number of constraints. This is due to the fact that the NMR spectra of Q2 have been acquired at a higher field (700 MHz) than Q1 (500 MHz).

Figure 2.

Side view representation of the superimposed 10 best structures of Q1 (A) and Q2 (B).

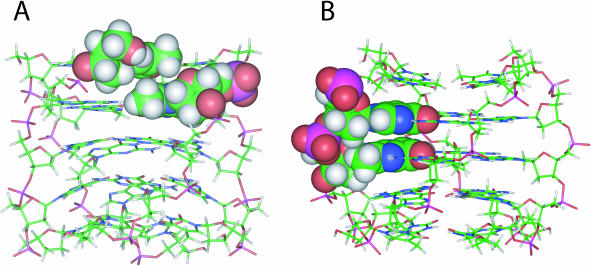

As expected, the four strands of the complex Q1 indicate a right-handed helical backbone geometry and are equivalent to each other. As a result, all the resulting quadruplex structures exhibit a 4-fold symmetry with all purine bases involved in the formation of G-tetrads, including the modified residues dGMe, that are able to form a well-defined and planar syn-tetrad while the other two G-quartets adopt an almost planar arrangement. Interestingly, unlike the arrangement assumed for dGBr residues in [d(TGBrGGT)]4 (10), all dGMe residues assume a perfectly syn-glycosidic conformation without causing any distorsions of the backbone (Figure 3A). This results in different stacking between the modified tetrads and the adjacent ones. In fact, while in the case of [d(TGBrGGT)]4 the five-membered rings of dGBr bases stack completely over the five-membered rings of the underneath guanines, as far as [d(TGMeGGT)]4 is concerned, the stacking between the first two tetrads of this structure involves both the purine rings to a partial extent.

Figure 3.

Side view of average structure of the best 10 structures of Q1 (A) and Q2 (B). Heavy atoms are shown with different colors (carbons, green; nitrogens, blue; oxygens, red; hydrogens, white); in panel A a dGMe and the adjacent dT residues and in panel B a dGMe and the adjacent dG residues are reported in CPK.

Q2, instead, is characterized by a right-handed helical twist and a 4-fold symmetry, as for Q1, but in this case all modified and canonical G residues constitute three planar anti-tetrads.

Furthermore, and in contrast to that which was observed for the analogue brominated quadruplex [d(TGGBrGT)]4 whereby C8-Br bonds of the modified guanines resulted in a slight distortion due to the presence of steric effects between bromines and the 5′-phosphate groups of guanosine of the adjacent strand, in this case it is of particular interest that the quadruplex structures obtained for Q2 are all characterized by a total lack of any steric interactions (Figure 3B). These differing results can be explained by taking into account the slight difference between van der Waals radii of methyl group compared with that of the bromine atom (27,28). In particular, the CPK representation of the Q1 and Q2 models (Figure 3) clearly demonstrates the absence of steric interactions involving methyl groups in both cases.

Furthermore, unlike the Q1 case, in Q2 the base stacking between the modified dGMe tetrad and the two adjacent canonical ones is rather poor. This is most probably due to the anti-glycosidic conformation of dGMe residues in [d(TGGMeGT)]4 notwithstanding the syn ones of [d(TGMeGGT)]4.

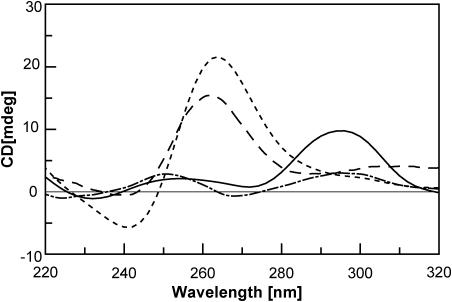

In order to determine the effects of the substitution of a regular dG residue with a dGMe one on the CD profile and the thermal stability of the resulting quadruplex structures, CD spectra and CD melting and annealing experiments were acquired for Q1, Q2 and Q3 samples.

In particular, the CD spectra of Q1 and Q2 were performed at 20°C, while the spectrum of Q3 was carried out at 5°C in order to maximize the quadruplex formation. As in the case of dGBr containing quadruplexes, the introduction of a dGMe residue in different positions of the same sequence 5′-d(TGGGT)-3′ provided very different CD spectra. Particularly, the CD spectrum of Q1 exhibited two positive bands at 254 and 295 nm and two negative ones at 232 and 272 nm. This is typical of anti-parallel quadruplex structures (29–31). On the contrary, the CD spectrum of Q2 proved to be very similar to that of other parallel stranded quadruplexes with all residues in an anti-glycosidic conformation characterized by maximum and minimum Cotton effects at 261 and 240 nm, respectively (29–31). As far as Q3 was concerned, its CD spectrum was characterised by a very small CD signal with two positive bands at 250 and 295 nm and a negative one at 267 nm. This unusual profile probably derived from the combination of the single-strand and quadruplex structure spectra that coexisted under the experimental conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

CD spectra of [d(TGGGT)]4 (------), 20°C; Q1 (–––––), 20°C; Q2 (— — —), 20°C; and Q3 (— - —), 5°C. Strands concentration = 10−4 M; solution: 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA pH = 7.0.

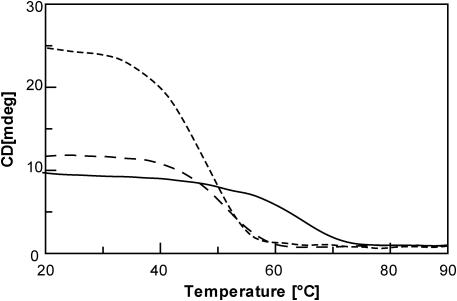

In order to estimate thermal stability, Q1, Q2 and Q3 were subjected to melting and annealing CD experiments in comparison with [d(TGGGT)]4, under the same experimental conditions. Taking into account that the rates of quadruplex formation/dissociation are very slow, we collected the data at 10°C/h. Unfortunately, a significant hysteresis emerged for each oligonucleotide comparing annealing and melting curves thereby indicating that, in spite of the very slow scan rate used, the systems were not at equilibrium. Therefore, considering the melting curves, the apparent melting temperature of 66, 52 and 45°C could be measured for Q1, Q2 and [d(TGGGT)]4, respectively, whereas it was not possible to estimate a melting temperature for Q3 because it began to melt at a temperature that was not experimentally accessible (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

CD thermal denaturation spectra of [d(TGGGT)]4 (-----), λ = 264 nm; Q1 (––––), λ = 295 nm; Q2 (— —), λ = 264 nm. Strands concentration = 10−4 M; solution: 10 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 70 mM KCl, 0.2 mM EDTA pH = 7.0. Scan rate 10°C/h.

These data demonstrates that, as in the case of dGBr containing quadruplexes, both the Q1 and Q2 complexes are thermally more stable than their unmodified counterpart, while the substitution of the dG at the 3′ position, with either a dGMe residue or a dGBr one, results in a decrease of the apparent melting temperatures, signifying that the thermal stability strictly depends upon the position of the modified base.

CONCLUSION

In this study we have demonstrated that replacing the three different dG residues one at a time with a dGMe in the sequence 5′-TGGGT-3′ affects the resulting structures in different ways. Particularly, ODNs 1 and 2 have been found to form 4-fold symmetric quadruplexes (Q1 and Q2, respectively) with all strands parallel and equivalent to each other, whereas the quadruplex structure formed by 3, specifically Q3, coexists with its single-strand which represents the major species at both 5 and 25°C. It is interesting to note that the quadruplex Q1 has been found to be characterized by an all syn GMe-tetrad and that this represents the first direct evidence of the occurrence of an all syn G-tetrad in a parallel quadruplex. On the other hand, although it has been established that purine bases bearing a methyl group or bromine substituent at the 8-position tend to assume a syn-glycosidic conformation (11,32,33), an anti-arrangement of the four dGMe residues has been found in the very stable parallel quadruplex Q2. Interestingly, Q1 and Q2 possess quite different CD profiles (Figure 4). In fact, although NMR data clearly indicate a parallel strand arrangement for both complexes, Q1 unlike Q2 shows a CD spectrum which is characteristic of an anti-parallel quadruplex. It should be noted, however, that the Q1 complex and anti-parallel quadruplexes share a common feature, namely, the presence of dG residues both in syn and anti-arrangements in the same sequence. This finding suggests that the CD profile generally observed for anti-parallel quadruplex structures could be ascribed to the presence of quadruplexes containing residues in syn-glycosidic conformations rather than to the relative orientation of the strands themselves. In fact, as CD spectra are very sensitive to base stacking in DNA (34,35), the concomitant presence of syn and anti dG in a G tract could alter the characteristic guanine–guanine stacking that is, according to the studies of Kypr et al. (36,37), responsible for a strong CD band of circa 260 nm. Nevertheless, further studies would be necessary to verify this hypothesis.

As far as the CD melting measurements are concerned, it is of note that Q1, Q2 and Q3 quadruplexes are characterized by thermal stabilities comparable to those observed for [d(TGBrGGT)]4, [d(TGGBrGT)]4 and [d(TGGGBrT)]4 (10), respectively.

In the light of the above findings, a re-examination of the initial hypothesis concerning the [d(TGGBrGT)]4 quadruplex that was assumed to possess an all syn GBr-tetrad is in order, considering that its CD spectrum is superimposable to that of [d(TGGMeGT)]4.

The results described in this article contribute further data to the structural features of the quadruplex with regards to the intricate relationship between the relative orientation of the strands, the glycosidic conformation of the G bases and the CD behaviour. Furthermore, the capacity of dGMe residues to stabilize parallel quadruplexes when present in specific positions may be of interest in the area of aptamers research whose core is often based upon quadruplex structures (38). In fact, a development of the SELEX process, the in vitro selection technique which utilizes combinatorial chemistry to produce ODN aptamers with high binding affinity and specificity towards a given target molecule, consists of modifications that can be introduced either into the initial randomized pool or subsequent to the selection of aptamer by chemical synthesis (39). In this frame, also considering the well tolerated presence of dGMe residues in templates during primer extension reactions (21), the incorporation of this modified base in the sequence could be a useful means to improve both the thermal stability of the selected aptamer and to introduce an alkyl group potentially able to establish hydrophobic interactions which may improve the affinity towards the target molecule.

Further research concerning ODNs containing more than one dGMe residue and a detailed thermodynamic analysis of quadruplex Q1 in order to elucidate the origin of the high stability are currently underway in our laboratories.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Italian M.U.R.S.T. (P.R.I.N. 2003 and 2004) and Regione Campania (L.41 and L.5). The authors are grateful to ‘Centro di Servizio Interdipartimentale di Analisi Strumentale’, C.R.I.A.S., for supplying NMR facilities. Francesco Zaccaria, Maria Giovanna Chini, Ada Virno, Rossella Pacchiano are acknowledged for their kind collaboration. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Italian M.U.R.S.T.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jeffery T.D. G-quartets 40 years later: from 5′-GMP to molecular biology and supramolecular chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:668–698. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J.J., Fang X., Tan W. Molecular aptamer beacons for real-time protein recognition. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;292:31–40. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S. Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2908–2916. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phan A.T., Modi Y.S., Patel D.J. Propeller-type parallel-stranded G-quadruplexes in the human c-myc promoter. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8710–8716. doi: 10.1021/ja048805k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel D.J., Bouaziz S., Kettani A., Wang Y. Structures of guanine-rich and cytosine-rich quadruplexes formed in vitro by telomeric, centromeric and triplet repeat disease DNA sequences. Oxford Handbook of Nucleic Acid Structure. 1999:389–453. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldrich E., O'Sullivan C.K. Ability of thrombin to act as molecular chaperone, inducing formation of quadruplex structure of thrombin-binding aptamer. Anal. Biochem. 2005;341:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou S-H., Chin K-H., Wang A.H.-J. DNA aptamers as potential anti HIV agents. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:231–234. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimjee S.M., Rusconi C.P., Sullenger B.A. Aptamer: an emerging class of therapeutics. Annu. Rev. Med. 2005;56:555–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.56.062904.144915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wlodarczyk A., Grzybowski P., Patkowski A., Dobek A. Effect of ions on the polymorphism, effective charge, and stability of human telomeric DNA. Photon correlation spectroscopy and circular dichroism studies. J. Phys. Chem. 2005;109:3594–3605. doi: 10.1021/jp045274d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito V., Randazzo A., Piccialli G., Petraccone L., Giancola C., Mayol L. Effects of an 8-bromodeoxyguanosine incorporation on the parallel quadruplex structure [d(TGGGT)]4. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2004;2:313–318. doi: 10.1039/b314672c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y., Ikeda R., Sugiyama H. 8-Methylguanosine: a powerful Z-DNA stabilizer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:13519–13524. doi: 10.1021/ja036233i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piotto M., Saudek V., Sklenar V.J. Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of aqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR. 1992;2:661–665. doi: 10.1007/BF02192855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeener J., Meier B., Bachmann H.P., Ernst R.R. Investigation of exchange processes by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunschweiler L., Ernst R.R. Coherence transfer by isotropic mixing: application to proton correlation spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 1983;53:521–528. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marion D., Wuthrich K. Application of phase sensitive two-dimensional correlated spectroscopy (COSY) for measurements of 1H–1H spin–spin coupling constants in proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983;113:967–974. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guntert P., Mumenthaler C., Wuthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijmenga S.S., van Buuren B.N.M. The use of NMR methods for conformational studies of nucleic acids. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1998;32:287–387. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gorenstein D.G. Phosphorus-31 NMR: principles and applications. NY: Academic Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roongta V.A., Jones C.R., Gorenstein D.G. Effect of distortions in the deoxyribose phosphate backbone conformation of duplex oligodeoxyribonucleotide dodecamers containing GT, GG, GA, AC, and GU base-pair mismatches on 31P NMR spectra. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5245–5258. doi: 10.1021/bi00474a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel P.K., Koti A.S.R., Hosur R.V. NMR studies on truncated sequences of human telomeric DNA: observation of a novel A-tetrad. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3836–3843. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.19.3836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohda K., Tsunomoto H., Minoura Y., Tanabe K., Shibutani S. Synthesis, miscoding specificity, and thermodynamic stability of oligodeoxynucleotide containing 8-Methyl-2′-deoxyguanosine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1996;9:1278–1284. doi: 10.1021/tx9601059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang K.Y., McCurdy S., Shea R.G., Swaminathan S., Bolton P.H. A DNA aptamer which binds to and inhibits thrombin exhibits a new structural motif for DNA. Biochemistry. 1993;32:1899–1904. doi: 10.1021/bi00059a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wüthrich K. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. NY: Wiley; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel P.K., Bhavesh N.S., Hosur R.V. Cation-dependent conformational switches in d-TGGCGGC containing two triplet repeats of fragile X syndrome: NMR observations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;270:967–971. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel P.K., Hosur R.V. NMR observation of T-tetrads in a parallel stranded DNA quadruplex formed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomere repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2457–2464. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith F.W., Feigon J. Strand orientation in the DNA quadruplex formed from the Oxytricha telomere repeat oligonucleotide d(G4T4G4) in solution. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8683–8692. doi: 10.1021/bi00084a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imashiro F., Takegoshi K., Hirayama K., Terao T., Saika A. Barriers to rotation of methyl groups in 4-methylacridine and related compounds. Side-on steric bulk of lone-pair electrons. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:1401–1404. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyburg S.C., Faerman C.H. A revision of van der Waals atomic radii for molecular crystals: nitrogen, oxygen, fluorine, sulfur, chlorine, selenium, bromine and iodine bonded to carbon. Acta Crystallogr. B. 1985;B41:274–279. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu M., Guo Q., Kallenbach N.R. Thermodynamics of G-tetraplex formation by telomeric DNAs. Biochemistry. 1993;32:598–601. doi: 10.1021/bi00053a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu M., Guo Q., Kallenbach N.R. Effect of thymine tract length on the structure and stability of model telomeric sequences. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3596–3603. doi: 10.1021/bi00065a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smirnov I., Shafer R.H. Effect of loop sequence and size on DNA aptamer stability. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1462–1468. doi: 10.1021/bi9919044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fàbrega C., Macìas M.J., Eritja R. Synthesis and properties of oligonucleotides containing 8-bromo-2′-deoxyguanosine. Nucleosides Nucleotides, Nucleic Acids. 2001;20:251–260. doi: 10.1081/ncn-100002085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Virgilio A., Esposito V., Randazzo A., Mayol L., Galeone A. Effects of 8-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine incorporation into quadruplex forming oligodeoxyriboncleotides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;13:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kypr J., Fialová M., Chládková J., Tůmová M., Vorlíčková M. Conserved guanine–guanine stacking in tetraplex and duplex DNA. Eur. Biophys. J. 2001;30:555–558. doi: 10.1007/s002490100174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kypr J., Vorlíčková M. Circular dichroism spectroscopy reveals invariant conformation of guanine runs in DNA. Biopolymers. 2002;67:275–277. doi: 10.1002/bip.10112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gray D.M., Tinoco I., Jr A new approach to the study of sequence-dipendent properties of polynucleotides. Biopolymers. 1970;9:223–244. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson W.C. Circular Dichroism: principles and applications. NY: VCH; 1994. CD of nucleic acids; pp. 523–540. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krawczyk S.H., Bischofberger N., Griffin L.C., Law V.S., Shea R.G., Swaminathan S. Structure-activity study of oligodeoxynucleotides which inhibit thrombin. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1995;14:1109–1116. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kusser W. Chemically modified nucleic acid aptamers for in vitro selections: evolving evolution. Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2000;74:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s1389-0352(99)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.