Abstract

The two haloacetate dehalogenase genes, dehH1 and dehH2, on the 65-kb plasmid pUO1 from Delftia acidovorans strain B were found to be located on transposable elements. The dehH2 gene was carried on an 8.9-kb class I composite transposon (TnHad1) that was flanked by two directly repeated copies of IS1071, IS1071L and IS1071R. The dehH1 gene was also flanked by IS1071L and a truncated version of IS1071 (IS1071N). TnHad1, dehH1, and IS1071N were located on a 15.6-kb class II transposon (TnHad2) whose terminal inverted repeats and res site showed high homology with those of the Tn21-related transposons. TnHad2 was defective in transposition because of its lacking the transposase and resolvase genes. TnHad2 could transpose when the Tn21-encoded transposase and resolvase were supplied in trans. These results demonstrated that Tn Had2 is a defective Tn21-related transposon carrying another class I catabolic transposon.

A variety of bacterial catabolic transposons that can degrade various xenobiotic compounds have been found in the past decade. They usually encode the functions for their own transposition so as to move to various sites in the genome without requiring DNA homology. Such characteristics of the catabolic transposons contribute to wide dissemination of the degradation genes among the divergent bacterial species through self-transmissible plasmids and/or conjugative transposons (22, 44). Their activities promote various kinds of DNA rearrangements, e.g., deletion, duplication, and inversion events, thus facilitating rapid evolution of some catabolic pathways (45, 50).

Bacterial catabolic transposons are categorized in two major groups based on their structural features. One group consists of the insertion sequence (IS) composite transposons, which carry the catabolic genes flanked by two copies of an IS element (23, 51). The other group consists of the class II (Tn3-like) transposons, which usually contain short (<50-bp) terminal inverted repeats (IRs), a transposase gene (tnpA), a resolvase gene (tnpR), and a resolution site (res) (36). In contrast to many class I transposons carrying various catabolic genes, only four elements have been identified as class II catabolic transposons (39-43). The best-characterized example of such transposons is Tn4653, which belongs to the Tn1722 subgroup and carries all of the toluene degradation (xyl) genes. Tn4653 contains another class II transposon, Tn4651, whose transposition-related genes are phylogenetically distant from those of the former transposon (41, 43), and the xyl genes in Tn4651 are bracketed by two copies of IS1246 (27, 32, 43), indicating that the xyl genes might have been incorporated as a composite transposon.

The soil bacterium Delftia acidovorans strain B (formerly Moraxella sp. strain B), isolated from industrial wastewater in Japan, produces two monohaloacetate dehalogenases: H-1, acting predominantly on fluoroacetate, and H-2, acting on chloro-, bromo-, and iodoacetate (17, 18). The genes for these dehalogenases, dehH1 and dehH2, respectively, are closely linked on a 65-kb self-transmissible plasmid, pUO1 (21). In a previous publication, we showed that the dehH2 gene was flanked by two directly repeated copies of a 1.8-kb sequence (Fig. 1A) (19) which was identical to a part of the 3.2-kb insertion element IS1071, an IS element originally identified on the chlorobenzoate transposon Tn5271 in Comamonas testosteroni BR60 (formerly Alcaligenes sp. strain BR60) (28, 31). IS1071 has a single open reading frame (ORF), whose product is related to the TnpA proteins of the class II transposons, and the transposition of the IS1071-flanked catabolic genes from one replicon to another has been demonstrated (15, 28, 29). IS1071 has also been found in other bacterial strains that metabolize aniline (12), carboxydiphenyl ethers (7), and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate (5), suggesting that IS1071 was profoundly involved in the wide spread of catabolic genes in many environmental bacterial species.

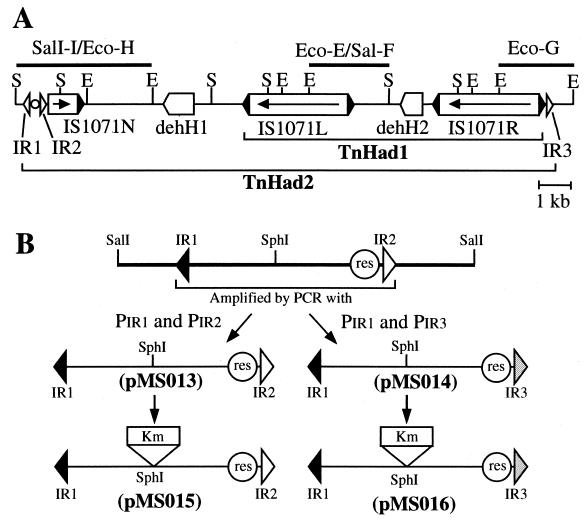

FIG. 1.

(A) Linear map of plasmid pUO1 around two dehalogenase genes, dehH1 and dehH2. The map is drawn based on the data of Kawasaki et al. (20) and indicates the 16.5-kb region whose sequence was determined previously (accession numbers D90422 and D90423 for dehH1 and deH2, respectively) (19) and in this study. The fragments sequenced in this study are shown by heavy lines, and their names are given above the lines. Symbols: open triangle, 37- or 38-bp IR; black triangle, 110-bp IR of IS1071; circle, res-like sequence. The arrow indicates the transcriptional direction of the tnpA gene in IS1071. Abbreviations for restriction sites: E, EcoRI; S, SalI. (B) Construction of mini-TnHad2 derivatives. The 817-bp fragment flanked by Tn21-like IRs was amplified using the SalI-I fragment as a template with primers PIR1 and PIR2 and primers PIR1 and PIR3, respectively (Table 2). The two PCR products were cloned into pSTV29 to generate pMS013 and pMS014, respectively. Subsequent insertion of the Kmr determinant into the SphI sites of pMS013 and pMS014 led to construction of pMS015 and pMS016, respectively.

In this study we determined the nucleotide sequence covering the dehH1 and dehH2 genes, and we also investigated the transposition of this region. The results indicated that (i) the dehH2 gene is indeed flanked by two copies of IS1071, to form TnHad1, and (ii) the dehH1 gene and TnHad1 are located within a defective class II transposon, TnHad2, that belongs to the Tn21-related transposons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and media.

The Escherichia coli strains used were DH1 (recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1), DH5α [F− φ80d lacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 deoR recA1 endA1 hsdR17 phoA supE44 λ− thi-1 gyrA96 relA1], and HB101 (hsdS20 recA13 ara-14 proA2 lacY1 galK2 rpsL20 xyl-5 mtl-1 supE44) (3). The plasmids used are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pUO1 | Tra+ HgrdehH1 dehH2 | 17 |

| R388 | Tra+ Tpr Sur | 46 |

| pUB307 | Tra+ Kmr Tcr; RK2 derivative with 5.5-kb deletion of Tn1 | 4 |

| pBR322 | Apr Tcr; cloning vector | 47 |

| pSTV29 | Cmr; cloning vector | TaKaRa Shuzo |

| pUC4K | Apr Kmr; cloning vector | 37 |

| pUC19 | Apr; cloning vector | 52 |

| pUC118 | Apr; cloning vector | 52 |

| pUC119 | Apr; cloning vector | 52 |

| pMS013 | Cmr; pSTV29 derivative carrying 817-bp fragment amplified with primers PIR1 and PIR2 (Fig. 1B) | This study |

| pMS014 | Cmr; pSTV29 derivative carrying 818-bp fragment amplified with primers PIR1 and PIR3a (Fig. 1B) | This study |

| pMS015 | Cmr Kmr; pMS013 derivative carrying Kmr determinant at unique SphI site in the 817-bp fragmentb (Fig. 1B) | This study |

| pMS015G | Cmr Kmr; pMS015 derivative having one G addition to IR2 | This study |

| pMS016 | Cmr Kmr; pMS014 derivative carrying Kmr determinant at unique SphI site in the 818-bp fragmentb (Fig. 1B) | This study |

| pMS018 | Cmr; pSTV29 derivative carrying the PCR-amplified IS1071 at KpnI site | This study |

| pMS016-388 | Tra+ Tpr Sur Cmr Kmr; cointegrate of pMS016 and R388 constructed in the presence of the Tn21 tnpA gene from pMT1252 | This study |

| pMS1071 | Apr; pUC19 derivative carrying the PCR-amplified IS1071 at KpnI site | This study |

| pMT1252 | Apr; pBR322 derivative carrying the res-tnpR-tnpA region of Tn21c | 43 |

| pMT1297 | Apr; pBR322 derivative carrying the res-tnpR-tnpA region of Tn1722c | 43 |

The PCR-amplified fragment is 1 bp longer than the original size because of the change of IR2 to IR3 (Fig. 1B; Table 2).

The SphI sites in the Kmr gene cassette are located at the outermost positions, and this cassette contains BamHI, SalI, and PstI sites (Table 2).

The Tn21 and Tn1722 derivatives, pMT1252 and pMT1297, respectively, lacked the tnpA-distal ends, leading to defects in their transposition.

L broth (LB) and LB agar were prepared as previously described (6). E. coli and D. acidovorans cells were cultivated at 37 and 30°C, respectively. Supplements added to the media were as follows: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 100 μg/ml; kanamycin, 100 μg/ml; streptomycin, 100 μg/ml; trimethoprim, 800 μg/ml; isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), 0.1 mM; and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal), 2 mM.

DNA methodology.

Established methods were employed for preparation of plasmid DNA, its digestion with restriction endonucleases, ligation, gel electrophoresis, and transformation of E. coli cells (3, 6, 34). Extraction of DNA fragments from agarose gels was done with a GFX PCR DNA and Gel Band Purification Kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The DNA fragments cloned into pUC19, pUC118, or pUC119 were sequenced by the chain termination method (35) using an ABI PRISM model 310 sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc.).

The distribution pattern of the 16S rRNA genes in strain B was investigated using the RiboPrinter Microbial Characterization System (DuPont).

PCR amplification and construction of plasmids.

Amplification of a part of the 16S rRNA gene was performed with primers 16S-20F and 16S-1400R (9) (Table 2). The 0.8-kb fragment flanked by IR1 and IR2 (Fig. 1B) was amplified with primers PIR1 and PIR2 (Table 2) with the SalI-I fragment as a template. Amplification of such a 0.8-kb fragment in which IR2 was replaced by IR3 was carried out using the same template but with primers PIR1 and PIR3 (Fig. 1B; Table 2). The SphI-flanked Kmr gene was amplified using primer Km-Sph with pUC4K as a template. PCR was performed with ExTaq DNA polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo Co. Ltd.) for 30 cycles consisting of 20 s at 94°C, 15 s at 55°C, and different extension times at 72°C (1 min for the 0.8-kb fragment, 80 s for the Kmr gene, and 90 s for the 16S rRNA gene). PCR amplification of the 3.2-kb IS1071 element with the primer 1071Kpn was performed using the same conditions except with an extension time of 3 min.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Name | Length | Sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 16S-20Fb | 30-mer | GGGGAAGCTTAGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG |

| 16S-1400Rb | 30-mer | GGGGAAGCTTTGACGGGCGGTGTGTACAAG |

| PIR1 | 60-mer | ACGTGAATTCGGGGTCGTCTCAGAAAACGGACAACAAAGCACGGTAAGCAAACCGGCATT |

| PIR2 | 60-mer | ACGTAAGCTTGGGTCGTCTCAGAAAACGGACAACAAAGCACGCTAAGGGCTGGCGTGTCA |

| PIR2Gc | 60-mer | ACGTAAGCTTGGGGTCGTCTCAGAAAACGGACAACAAAGCACGCTAAGGGCTGGCGTGTC |

| PIR3d | 60-mer | ACGTAAGCTTGGGGTCGCCTCAGAAAACGGAAAATAAAGCACGCTAAGGGCTGGCGTGTC |

| 1071Kpn | 30-mer | ACGTGGTACCGGGGTCTCCTCGTTTTCAGT |

| Km-Sph | 30-mer | TTTTGCATGCCCCGGATCC GTCGAC CTGCA |

Underlining indicates restriction sites: BamHI, GGATCC; EcoRI, GAATTC; HindIII, AAGCTT; KpnI, GGTACC; SalI, GTCGAC; SphI, GCATGC; and PstI, CTGCAG (incomplete in the Km-Sph primer). Boldface indicates the 37- or 38-bp IR similar to that of Tn21 (Fig. 2C).

Primers 16S-20F and 16S-1400R (9) were used to amplify the 16S rRNA gene from D. acidovorans B.

PIR2G was used to construct the mini-TnHad2 derivative by addition of one G residue to the IR2 sequence.

PIR3 was used to construct the mini-TnHad2 derivative by replacement of IR2 with IR3 (Fig. 1B).

The two 0.8-kb products flanked by the Tn21-like IRs (IR1-IR2 and IR1-IR3) were cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pSTV29 to construct pMS013 and pMS014, respectively (Fig. 1B). Insertion of the PCR-amplified Kmr determinant at the SphI sites of pMS013 and pMS014 generated pMS015 and pMS016, respectively (Fig. 1B). Insertion of the PCR-amplified IS1071 element into the KpnI sites of pSTV29 and pUC19 gave rise to pMS018 and pMS1071, respectively.

Assay of transposition.

Transposition of the TnHad2 derivatives was assayed by the mating-out experiment described previously (40). For this purpose, we constructed an E. coli DH5α derivative carrying the following three plasmids: R388, a conjugal plasmid free of transposons (46); a pSTV29-based Kmr plasmid carrying the TnHad2 derivative (pMS015 or pMS016); and a pBR322-based plasmid carrying relevant tnpA and tnpR genes (pMT1252 or pMT1297). Such a strain was employed as the donor to mate with HB101 on a membrane filter (40), and Kmr Smr transconjugants were selected. The transposition frequency was expressed as the number of Kmr Smr transconjugants per Tpr Smr transconjugant. The Kmr transconjugants were analyzed for their plasmid profiles. To investigate resolution, the pBR322-based plasmid carrying a relevant tnpR gene was introduced into Kmr Smr transconjugants harboring the stable cointegrate of R388 and a pSTV29-based plasmid connected by the transposon. After overnight cultivation of the resulting strain in LB, the stability of the cointegrate was investigated by physical detection of the resolved replicons. DH1(pUB307)(pMS018) was mated with HB101 to examine the transposition of IS1071 by selecting Cmr Smr transconjugants.

Sequence analysis.

A computer analysis of the sequences was performed with the programs GENETYX 10 (SDC Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and BLAST 2 (National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences described in this paper have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers AB049197 (TnHad1), AB049198 (TnHad2), and AB074256 (16S rRNA gene).

RESULTS

Phylogenetic analysis of strain B.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence from strain B, originally described tentatively as a Moraxella strain, had significant identities with the corresponding portions of the 16S rRNA genes of the D. acidovorans type strain (99.0%) and another D. acidovorans strain (99.9%). Various phenotypic properties of this strain (data not shown) are also similar to those of the D. acidovorans type strain (48). Our further study using the RiboPrinter Microbial Characterization System (DuPont) indicated that strain B had a distribution pattern of the rRNA genes identical to that of D. acidovorans strains but not to that of Moraxella species (data not shown). Therefore, in this study we changed the organism's taxonomic affiliation to D. acidovorans B.

Identification of TnHad1.

The 2.4-kb Eco-E/Sal-F and 2.2-kb Eco-G fragments of pUO1 (Fig. 1A) were sequenced. These nucleotide sequences together with our previous sequence data revealed a 8.9-kb contiguous region in which the dehH2 gene was flanked by two directly repeated copies of a 3,204-bp sequence. This sequence was identical to that of the IS1071 on plasmid pADP-1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP (25) and plasmid pTSA from C. testosteroni T-2 (15, 38) and was 99.8% homologous (3,199 of 3,204 nucleotides) to that of the original IS1071 element (28). Our IS1071 sequence carried the 110-bp terminal IRs and was predicted to encode the TnpA protein, with a size of 971 amino acids (aa). Our tnpA gene differed at five nucleotides (two substitutions and three additions) from that of the original IS1071 element, leading to one amino acid substitution at position 135 and one amino acid addition-deletion at position 137 of the products. Based on its structural features of the composite transposons, the 8.9-kb element was designated TnHad1. We hereafter designate our two IS1071 elements IS1071R and IS1071L (Fig. 1A and 2A). Neither IS1071 element had nucleotide duplications at its external junctions.

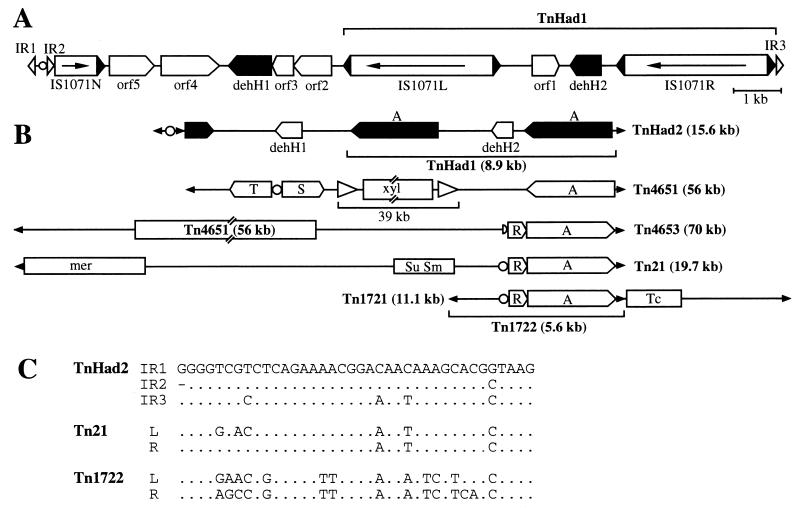

FIG. 2.

Structure of TnHad2 and its related transposons. (A) Structure of TnHad2, which includes a composite transposon, TnHad1. The arrow in IS1071 represents the transcriptional direction of the tnpA gene. The pentagon indicates the orientation of a putative ORF. (B) Schematic structures of representative class II transposons, based on our previous publication (39). Symbols: filled arrowhead, terminal 37- or 38-bp IR; open arrowhead, IS1246 (32); circle, res site; half circle, defective res site; A, tnpA; R, S, and T, genes for cointegrate resolution; xyl, xyl genes; mer, genes for resistance to mercuric ion; Sm, gene for resistance to Sm; Su, gene for resistance to sulfonamide; Tc, gene for resistance to tetracycline. (C) Comparison of the TnHad2 IRs with those of Tn21 and Tn1722. The left (L) and right (R) ends of each transposon are defined as those located distal and proximal, respectively, to the tnpA gene. Sequence data for the transposons other than TnHad2 are compiled from the GenBank database: Tn21, AF071413; Tn1722, X61367. Dots indicate identical nucleotides at the same position as in the IR1 of TnHad2, and a hyphen indicates an absent nucleotide.

The PCR-amplified fragment of our IS1071 element was cloned into pSTV29 to construct pMS018. DH1(pUB307)(pMS018) and DH1(pUB307)(pSTV29) were used as the donor strains to mate with HB101. The former, but not the latter, donor strain gave rise to Cmr Smr transconjugants at a frequency of 1.3 × 10−7. The transconjugants carried a single species of plasmids with the same size. Restriction analysis of the plasmids revealed that each plasmid was the cointegrate of pUB307 and pMS018 connected by two copies of IS1071, one at each junction.

TnHad1 had an additional ORF (orf1) encoding a 188-aa protein (Fig. 2A) that showed significant homology to the N-terminal region of a hypothetical 288-aa protein of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 (67%; accession number AE004686) and putative tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenases of Mesorhizobium loti (62%; AP002995) and Deinococcus radiodurans R1 (51%; AE001863). We did not investigate the expression of orf1.

Identification of TnHad2.

Just downstream of IS1071R was a 38-bp sequence (IR3) highly homologous to that of the Tn21 IRs (Fig. 1A and 2C) (8). Class II transposons usually carry 38-bp IRs at their ends, and their IRs are closely related to one another (14). To find out whether pUO1 carried additional copies of such a 38-bp sequence, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the 4.2-kb region (SalI-I/Eco-H) located upstream of IS1071L (Fig. 1A). There was a third truncated copy of IS1071 (IS1071N) located 4.9 kb from IS1071L (Fig. 1A and 2A). IS1071N carried the 3′ part (983 bp) of IS1071, and its orientation was opposite to that of IS1071L and IS1071R (Fig. 1A and 2A). Just upstream of the IS1071N there was an 817-bp fragment flanked by 38-and 37-bp sequences (designated IR1 and IR2, respectively) that were very similar to those of IR3 and Tn21 (Fig. 2C). As a result, IR1 and IR3 were found to cover the 15,604-bp sequence that included TnHad1, dehH1, and IS1071N (Fig. 1A and 2A). Based on its structural similarity to those of the class II transposons, the 15.6-kb element was designated TnHad2.

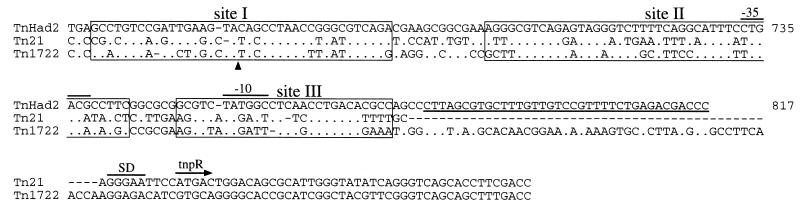

TnHad2 on pUO1 was flanked by 5-bp direct repeats of the TTTCT sequence, indicating that TnHad2 might have transposed from another replicon to the ancestral form of pUO1. TnHad2 did not carry DNA sequences homologous to the tnpR and tnpA genes of the Tn21-related transposons (14) (Fig. 2B). However, a 130-bp sequence showing 60% homology to the res sites in Tn21 and Tn1722 (1, 8) was located between IR1 and IR2 (Fig. 3). The res site of the class II transposon was composed of three resolvase-binding domains (sites I, II, and III) that contained the crossover point for the cointegrate resolution and the −35 and the −10 sequences of the tnpR promoter, respectively (33). Such domains appeared to be conserved in the putative res site of TnHad2 (Fig. 3). Except for the three IRs and the putative res site, no additional sequences that were similar to those of the Tn21-related transposons were found.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the TnHad2 res sequence with those of Tn21 and Tn1722. The numbers on the right are base positions, taking the 5′-end nucleotide of TnHad2 as position 1. Dots represent nucleotides identical to those of TnHad2, whereas hyphens represent gaps that result in maximum matching. Three putative resolvase-binding sites are boxed, and the crossover point in Tn21 and Tn1722 is indicated by an arrowhead (33). The translational start of the tnpR gene is indicated by a horizontal arrow, and the promoter and ribosome-binding (SD) sequences are overlined. The 37-bp IR2 sequence is underlined.

The nucleotide sequence between IS1071L and IS1071N carried four ORFs, orf2 to orf5 (Fig. 2A). Homology searches revealed that (i) the predicted 252-aa product of orf2 had 67% homology to a hypothetical protein of P. aeruginosa PAO1 (accession number AE004696) and (ii) the predicted 323-aa product of orf5 had 26% homology to several proteins belonging to the LysR-type transcriptional regulators and had a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif of LysR-type transcriptional regulators. The predicted polypeptide sequences from orf3 and orf4 showed no significant homology with other proteins in the databases.

Transposition of TnHad2.

The sequence analysis described above indicated that TnHad2 had IRs and a putative res site highly homologous to those of the Tn21-related transposons. We investigated the transposition of TnHad2 in the presence of the tnpA and tnpR genes of the well-studied Tn21-related transposons Tn21 and Tn1722 (1, 8), whose TnpR functions, but not TnpA functions, are exchangeable (11, 13).

Plasmids pMS015 and pMS016, each of which had a TnHad2 derivative carrying the pUO1-derived 0.8-kb sequence and the Kmr determinant, were constructed and used for the transposition experiment (Fig. 1B). Each plasmid was introduced into a DH5α derivative harboring R388 and a pBR322-based plasmid carrying the relevant tnpA and tnpR genes, and the resulting strain was used as the donor to mate with HB101. Use of the donor strain carrying pMT1252, but not those carrying pBR322 or pMT1297, led to formation of the Kmr Smr transconjugants (Table 3). All the IRs of the class II transposons commonly have the four G residues at the outermost positions (14, 36). The corresponding region of IR2 on pMS015 contained only three G residues. Transposition from pMS015 was observed at a 10-fold-lower frequency than that from pMS016. However, use of pMS015G, in which one G residue was added to the outermost end of IR2, led to 10-fold increase in the frequency of the formation of the transconjugants (Table 3). Detailed analysis of transconjugants by restriction digestion revealed that (i) 10% of the transconjugants carried the R388 derivatives with the insert of the mini-TnHad2 element and (ii) each of the remaining transconjugants carried a stable cointegrate of R388 and pSTV29-based plasmid that was connected by two directly repeated copies of the mini-TnHad2 element, one at each junction. Insertion of each TnHad2 derivative into R388 generated a 5-bp duplication of the target sequence, e.g., AAGAA, CAATA, or TGACT. The ends of the mini-TnHad2 insert in the R388 derivatives were a combination of IR1 and IR3 and a combination of IR1 and a G residue plus IR2 when pMS016 and pMS015G, respectively, were employed as the donor plasmids. It is noteworthy that when pMS015 was employed, the IR2 end of the insert possessed, at the outermost position, an additional T residue that corresponded to the nucleotide adjacently located at the outermost three G residues of the IR2 on pMS015 (Table 2). Those results revealed that IR1, IR2, IR3, and the res site in TnHad2 could function in cis in the presence of the Tn21-encoded TnpA and TnpR proteins and that the Tn1722-encoded TnpA protein did not catalyze the cointegration of the mini-TnHad2 derivatives. We could not observe the mini-TnHad2 transposition when an IS1071-containing plasmid, pMS1071, was employed to supply its TnpA protein in trans.

TABLE 3.

Transposition of the TnHad2 derivativesa

| Donor plasmid (flanking IRs) | Transposition frequencyb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| pBR322 | pMT1252 (Tn21) | pMT1297 (Tn1722) | |

| pMS016 (IR1 and IR3) | <3.4 × 10−8 | 1.8 × 10−2 | <8.0 × 10−7 |

| pMS015 (IR1 and IR2) | <2.5 × 10−7 | 2.0 × 10−3 | <1.7 × 10−7 |

| pMS015G (IR1 and IR2G) | <3.7 × 10−8 | 1.5 × 10−2 | <4.4 × 10−7 |

The donor plasmid was a pSTV29-based plasmid with an insert of the PCR-amplified 0.8-kb fragment bracketed by heterologous Tn21-like IRs (Fig. 1B). The complementing plasmid was a pBR322-based plasmid carrying the tnpR and tnpA genes of Tn21 or Tn1722.

The transposition frequency is expressed as the number of the Kmr transconjugants per Tpr transconjugant. All values are averages from at least three independent experiments.

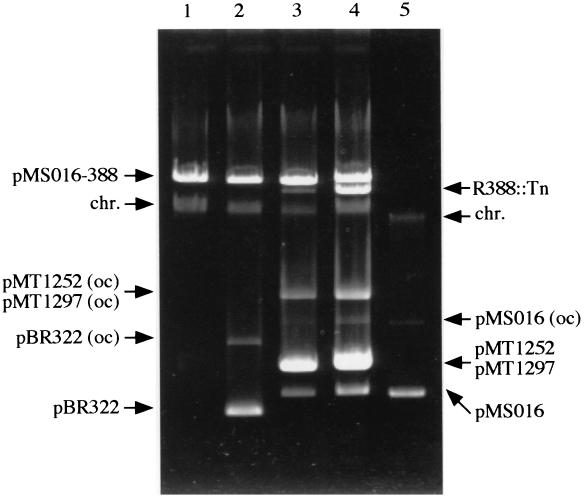

It has been demonstrated that the resolution functions were exchangeable between Tn21 and Tn1722 (11). We therefore investigated whether or not the TnHad2-mediated cointegrate could resolve in the presence of the Tn1722 TnpR protein. An HB101 derivative harboring the stable cointegrate of pMS016 and R388 (designated pMS016-388) connected by the mini-TnHad2 derivative was transformed with pBR322, pMT1252, or pMT1297, and the resolution of pMS016-388 was examined (Fig. 4). In the presence of pMT1252 or pMT1297, but not pBR322, pMS016-388 resolved to generate the two species of plasmids. The resolved plasmids were separately introduced into DH1 by transformation and conjugation. Restriction and sequence analysis confirmed that the resolved plasmids were pMS016 and an R388 derivative with an insertion of the mini-TnHad2 derivative. This indicated that the Tn21 and Tn1722 tnpR products could resolve the TnHad2-mediated cointegrate.

FIG. 4.

Resolution of stable cointegrates. An HB101 derivative harboring pMS016-388, a stable cointegrate of pMS016 and R388, was transformed with pBR322, pMT1252, and pMT1297. After overnight cultivation of the resulting strains in LB, the cleared lysate prepared from each strain was electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel. Lane 1, lysate from HB101(pMS016-388); lane 2, lysate from HB101(pMS016-388)(pBR322); lane 3, lysate from HB101(pMS016-388)(pMT1252); lane 4, lysate from HB101(pMS016-388)(pMT1297); lane 5, pMS016. R388::Tn, R388::mini-TnHad2; chr., chromosomal DNA; oc, open circular form. The sizes of pMT1252 and pMT1297 are nearly identical (6.4 kb).

DISCUSSION

In this study we have presented the contiguous 15.6-kb nucleotide sequence covering the two dehalogenase genes and have investigated its transposition. The results indicated that (i) the dehH2 gene was flanked by two copies of IS1071 to form TnHad1 and (ii) TnHad1 was, together with the dehH1 gene, located within the larger transposon TnHad2. Despite lacking the tnpA and tnpR genes, TnHad2 had the common features of the Tn21-related transposons, i.e., the terminal 38-bp IRs, the 5-bp duplication at the target site upon transposition, and the res site at which the tnpR products of the Tn21-related transposons could resolve the cointegrate. We further classified TnHad2 in the Tn21 subgroup (11, 13, 14) because (i) transposition of the TnHad2 derivatives was detected with supply of the Tn21 tnpA product but not with supply of the Tn1722 tnpA product and (ii) the Tn21- and Tn1722-specified TnpR proteins resolved the TnHad2-mediated cointegrate. However, except for the IRs and the res site, the TnHad2 sequence shows no similarity with those of the Tn21-related transposons. TnHad2 must have lost the Tn21-related region containing the tnpR and tnpA genes by unknown DNA rearrangements.

We have previously reported that the coexistence of pUO1 with plasmid RP4 in the same Pseudomonas cells led to frequent genetic exchange between the two plasmids and that such exchange events gave rise to the two groups of the RP4 derivatives: one carrying the dehH2 gene alone and the other carrying both the dehH1 and dehH2 genes (16). However, the pUO1-derived regions on the RP4 derivatives were different from TnHad1 and TnHad2 (data not shown), suggesting that transposition of the two transposons must not have been responsible for the formation of the RP4 derivatives. More detailed analysis of the structures of such plasmids will provide some clues to show the molecular mechanism(s) of the genetic exchange events.

The outermost four G residues are conserved in all known members of the class II transposons (14, 36), and the importance of these G residues for transposition has been documented by mutant analysis of Tn3, Tn21, and Tn1000 (2, 24, 26, 30, 49). Grindley's group has reported that a G-to-T mutation at one of the outermost three positions and G-to-C mutations at the outermost two positions in both IRs of Tn1000 abolished transposition (26, 49). G-to-T mutations at the outermost two positions in both IRs of Tn3 were also reported to abolish the transposition (2). However, it has been indicated that mutant transposons of Tn3 and Tn1000 carrying a wild-type IR and a mutant IR (change of 5′-GGGG-3′ to 5′-TTGG-3′ in Tn3 and to 5′-CCGG-3′ in Tn1000) were still transposable, although the transposition frequency was 200- to 500-fold lower than that of the wild type (2, 49). Unfortunately, sequence analyses were not carried out to determine the ends of the transposed region of the mutant transposons. We showed in this study that (i) one of the TnHad2 derivatives which had the outermost three G residues in IR2 (on pMS015) could normally transpose to another replicon, (ii) addition of a G residue to the outermost end of IR2 (on pMS015G) led to a 10-fold increase in frequency of the transposition (Table 3), and (iii) the outermost IR2 end of the transposed region from pMS015 had the 5′-TGGG-3′ sequence. These results indicated that when at least one of the IRs had the outermost four G residues, the Tn21 transposase could also recognize the 5′ part of the T residue of another IR to perform cointegration. This is consistent with the previous report by Amemura-Maekawa and Ohtsubo (2) that the defect of a mutant IR of one end in Tn3 could be compensated for by the wild-type IR of another end. It is of interest whether this situation is the case in other class II transposons.

As a class II transposon, IS1071 usually generates, upon its transposition, a 5-bp duplication of the target sequence (our unpublished data). However, no such duplicated sequences were detected at the four junctions of the two IS1071 copies of the chlorobenzoate catabolic transposon Tn5271 on pBRC60 (10, 28, 51). Wyndham et al. have proposed a likely model for the formation of IS1071-flanked transposons having no target duplication on the plasmid. According to their model, the initial step is integration of an IS1071-containing plasmid near the chromosomal catabolic genes by the IS1071-encoded cointegration function. This integration leads to the 5-bp duplication of the integration site. The next step is intrachromosomal transposition of one copy of IS1071 to another chromosomal target located on the other site of the catabolic genes. This two-step transposition event would result in generation of a plasmid derivative in which the catabolic genes flanked by the two copies of IS1071 had no apparent 5-bp duplication at the four junctions of the IS1071. This model is consistent with our results with TnHad1 because (i) each IS1071 element on TnHad1 had no nucleotide duplication at the four junctions, (ii) the GC content of the IS1071-flanked intervening sequence (60%) was much lower than that of the backbone region of pUO1 (66%) (our preliminary unpublished data), and (iii) the codon usage of the predicted amino acid sequences of orf1 and dehH2 differed considerably from those encoded by the genes of the backbone region of pUO1 (our preliminary unpublished data).

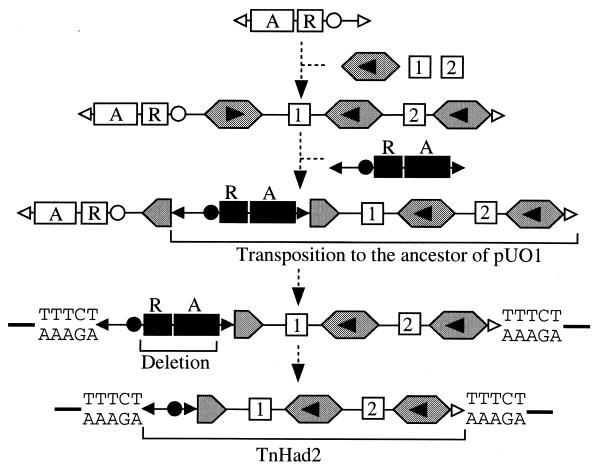

TnHad2 had a very complicated structure, carrying TnHad1, a truncated version of IS1071, and three IRs (IR1, IR2, and IR3) (Fig. 2A), suggesting that there might have been several steps of unknown recombination events to give rise to the present structure of TnHad2. It is therefore difficult to draw the sequential steps of its evolutionary history. However, TnHad2 had, in contrast to TnHad1, the 5-bp target duplication on pUO1, indicating that this transposon or its ancestor must have been inserted into the ancestral form of pUO1. TnHad2 had the functional res site between IR1 and IR2 and had a third IR, IR3, that was located 14.8 kb away from IR2. When we consider (i) the higher homology between IR1 and IR2 than between IR1 and IR3, (ii) the presence of the truncated version of IS1071 (IS1071N) just downstream of IR2, and (iii) the absence of tnpA and tnpR genes in TnHad2, one of the likely scenarios to form TnHad2 might be as follows: (i) insertion of a Tn21-related transposon into an intact version of IS1071N residing in another TnHad1- and dehH1-containing Tn21-related transposon, (ii) transposition of the TnHad1- and dehH1-containing region using two heterogenous IRs of the two Tn21-related transposons, and (iii) deletion of the contiguous tnpR-tnpA region (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

A likely model for generation of TnHad2. Symbols: hexagon, IS1071; horizontal arrowhead in the hexagon, transcriptional direction of tnpA gene; black and white arrowheads, terminal IRs; black and white circles, res sites; A, tnpA; R, tnpR; 1, dehH1; 2, dehH2. See text for details. The TTTCT sequence indicates the 5-bp direct repeat on pUO1.

Our results in this study demonstrated structural similarity between TnHad2 and Tn4651 in that both transposons carry the IS1071 and IS1246 composite catabolic transposons. The IS1071 composite catabolic transposon Tn5271 has also been proposed to be covered within Tn5272, whose detailed properties have not yet been investigated (51). Analysis of Tn5272 will clarify its structural similarity with TnHad2.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to H. Sawada for his advice on identification of our bacterial strain.

This work was carried out under contract with the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan. This work was also supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allmeier, H., B. Cresnar, M. Greck, and R. Schmitt. 1992. Complete nucleotide sequence of Tn1721: gene organization and a novel gene product with features of a chemotaxis protein. Gene 111:11-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amemura-Maekawa, J., and E. Ohtsubo. 1991. Functional analysis of the two domains in the terminal inverted repeat sequence required for transposition of Tn3. Gene 103:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. Wiley, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Bennett, P. M., J. Grinsted, and M. H. Richmond. 1977. Transposition of TnA does not generate deletions. Mol. Gen. Genet. 154:205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clement, P., D. H. Pieper, and B. Gonzalez. 2001. Molecular characterization of a deletion/duplication rearrangement in tfd genes from Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4) that improves growth on 3-chlorobenzoic acid but abolishes growth on 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid. Microbiology 147:2141-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, L., M. Kuehl, and J. Battey. 1994. Basic methods in molecular biology, 2nd ed. Appleton & Lange, East Norwalk, Conn.

- 7.Dehmel, U., K. H. Engesser, K. N. Timmis, and D. F. Dwyer. 1995. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the gene encoding a novel dioxygenase involved in metabolism of carboxydiphenyl ethers in Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes POB310. Arch. Microbiol. 163:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de la Cruz, F., and J. Grinsted. 1982. Genetic and molecular characterization of Tn21, a multiple resistance transposon from R100.1. J. Bacteriol. 151:222-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Devereux, R., and S. G. Willis. 1995. Amplification of ribosomal RNA sequences, p. 3.3.1-3.3.11. In F. de Bruijn (ed.), Molecular microbial ecology manual. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 10.Di Gioia, D., M. Peel, F. Fava, and R. C. Wyndham. 1998. Structures of homologous composite transposons carrying cbaABC genes from Europe and North America. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:1940-1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diver, W. P., J. Grinsted, D. C. Fritzinger, N. L. Brown, J. Altenbuchner, P. Rogowsky, and R. Schmitt. 1983. DNA sequences of and complementation by the tnpR genes of Tn21, Tn501 and Tn1721. Mol. Gen. Genet. 191:189-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukumori, F., and C. P. Saint. 1997. Nucleotide sequences and regulational analysis of genes involved in conversion of aniline to catechol in Pseudomonas putida UCC22(pTDN1). J. Bacteriol. 179:399-408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grinsted, J., F. de la Cruz, J. Altenbuchner, and R. Schmitt. 1982. Complementation of transposition of tnpA mutants of Tn3, Tn21, Tn501, and Tn1721. Plasmid 8:276-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grinsted, J., F. de la Cruz, and R. Schmitt. 1990. The Tn21 subgroup of bacterial transposable elements. Plasmid 24:163-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Junker, F., and A. M. Cook. 1997. Conjugative plasmids and the degradation of arylsulfonates in Comamonas testosteroni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:2403-2410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawasaki, H., M. Takao, A. Koiso, and K. Tonomura. 1985. Genetic rearrangement of plasmids: in vivo recombination between a dehalogenation plasmid and multiple-resistance plasmid RP4 in Pseudomonas sp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49:1544-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawasaki, H., N. Tone, and K. Tonomura. 1981. Plasmid-determined dehalogenation of haloacetates in Moraxella species. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45:29-34. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki, H., N. Tone, and K. Tonomura. 1981. Purification and properties of haloacetate halidohydrolase specified by plasmid from Moraxella sp. strain B. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45:35-42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kawasaki, H., K. Tsuda, I. Matsushita, and K. Tonomura. 1992. Lack of homology between two haloacetate dehalogenase genes encoded on a plasmid from Moraxella sp. strain B. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138:1317-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kawasaki, H., H. Yahara, and K. Tonomura. 1983. Cleavage maps of dehalogenation plasmid pUO1 and its derivative harbored in Moraxella sp. Agric. Biol. Chem. 47:1639-1641. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki, H., H. Yahara, and K. Tonomura. 1981. Isolation and characterization of plasmid pUO1 mediating dehalogenation of haloacetate and mercury resistance in Moraxella sp. B. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45:1477-1481. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mahillon, J. 1998. Transposons as gene haulers. APMIS Suppl. 106:29-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahillon, J., and M. Chandler. 1998. Insertion sequences. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:725-774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin, C., J. Grinsted, and F. de la Cruz. 1989. Effects of variation of inverted-repeat sequences on reactions mediated by the transposase of Tn21. J. Bacteriol. 171:3996-4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martinez, B., J. Tomkins, L. P. Wackett, R. Wing, and M. J. Sadowsky. 2001. Complete nucleotide sequence and organization of the atrazine catabolic plasmid pADP-1 from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP. J. Bacteriol. 183:5684-5697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.May, E. W., and N. D. Grindley. 1995. A functional analysis of the inverted repeat of the γδ transposable element. J. Mol. Biol. 247:578-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meulien, P., R. G. Downing, and P. Broda. 1981. Excision of the 40kb segment of the TOL plasmid from Pseudomonas putida mt-2 involves direct repeats. Mol. Gen. Genet. 184:97-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakatsu, C., J. Ng, R. Singh, N. Straus, and C. Wyndham. 1991. Chlorobenzoate catabolic transposon Tn5271 is a composite class I element with flanking class II insertion sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:8312-8316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ng, J., and C. Wyndham. 1993. IS1071-mediated recombinational equilibrium in Alcaligenes sp. BR60 carrying the 3-chlorobenzoate catabolic transposon Tn5271. Can. J. Microbiol. 39:92-100. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nissley, D. V., F. G. Lindh, and M. A. Fennewald. 1990. Mutational analysis of the inverted repeats of Tn3. J. Mol. Biol. 213:671-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Providenti, M. A., and R. C. Wyndham. 2001. Identification and functional characterization of CbaR, a MarR-like modulator of the cbaABC-encoded chlorobenzoate catabolism pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3530-3541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy, B. R., L. E. Shaw, J. R. Sayers, and P. A. Williams. 1994. Two identical copies of IS1246, a 1275 base pair sequence related to other bacterial insertion sequences, enclose the xyl genes on TOL plasmid pWW0. Microbiology 140:2305-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogowsky, P., S. E. Halford, and R. Schmitt. 1985. Definition of three resolvase binding sites at the res loci of Tn21 and Tn1721. EMBO J. 4:2135-2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherratt, D. 1989. Tn3 and related transposable elements: site-specific recombination and transposition, p. 163-184. In D. E. Berg and M. M. Howe (ed.), Mobile DNA. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 37.Taylor, L. A., and R. E. Rose. 1988. A correction in the nucleotide sequence of the Tn903 kanamycin resistance determinant in pUC4K. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tralau, T., A. M. Cook, and J. Ruff. 2001. Map of the IncP1β plasmid pTSA encoding the widespread genes (tsa) for p-toluenesulfonate degradation in Comamonas testosteroni T-2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1508-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuda, M., and H. Genka. 2001. Identification and characterization of Tn4656, a novel class II transposon carrying a set of toluene-degrading genes from TOL plasmid pWW53. J. Bacteriol. 183:6215-6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsuda, M., and T. Iino. 1987. Genetic analysis of a transposon carrying toluene degrading genes on a TOL plasmid pWW0. Mol. Gen. Genet. 210:270-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuda, M., and T. Iino. 1988. Identification and characterization of Tn4653, a transposon covering the toluene transposon Tn4651 on TOL plasmid pWW0. Mol. Gen. Genet. 213:72-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsuda, M., and T. Iino. 1990. Naphthalene degrading genes on plasmid NAH7 are on a defective transposon. Mol. Gen. Genet. 223:33-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuda, M., K. Minegishi, and T. Iino. 1989. Toluene transposons Tn4651 and Tn4653 are class II transposons. J. Bacteriol. 171:1386-1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuda, M., H. M. Tan, A. Nishi, and K. Furukawa. 1999. Mobile catabolic genes in bacteria. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 87:401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Meer, J. R., W. M. de Vos, S. Harayama, and A. J. Zehnder. 1992. Molecular mechanisms of genetic adaptation to xenobiotic compounds. Microbiol. Rev. 56:677-694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward, J. M., and J. Grinsted. 1982. Physical and genetic analysis of the Inc-W group plasmids R388, Sa, and R7K. Plasmid 7:239-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson, N. 1988. A new revision of the sequence of plasmid pBR322. Gene 70:399-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen, A., M. Fegan, C. Hayward, S. Chakraborty, and L. I. Sly. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the Comamonadaceae, and description of Delftia acidovorans (den Dooren de Jong 1926 and Tamaoka et al. 1987) gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49:567-576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiater, L. A., and N. D. Grindley. 1990. Uncoupling of transpositional immunity from γδ transposition by a mutation at the end of γδ. J. Bacteriol. 172:4959-4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams, P. A., and J. R. Sayers. 1994. The evolution of pathways for aromatic hydrocarbon oxidation in Pseudomonas. Biodegradation 5:195-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wyndham, R. C., A. E. Cashore, C. H. Nakatsu, and M. C. Peel. 1994. Catabolic transposons. Biodegradation 5:323-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]