The fumonisins, a family of food-borne carcinogenic mycotoxins, were first isolated in 1988 (21) from cultures of Fusarium verticillioides (Sacc.) Nirenberg (previously known as Fusarium moniliforme Sheldon). During the same year, the structures of the fumonisins were elucidated (6) and fumonisin B1 was shown to cause equine leukoencephalomalacia (34). There have been numerous publications dealing with this group of novel, carcinogenic mycotoxins, and comprehensive reviews of different aspects of the fumonisins are available (20, 22, 23, 24, 35, 36, 37, 41, 43, 46, 52, 55, 60, 61, 66). Due to the widespread occurrence of the fumonisins in maize, a dietary staple in many countries, the carcinogenic risk of fumonisins to humans was evaluated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer in 1993, and the toxins produced by F. moniliforme were evaluated as “Group 2B carcinogens,” i.e., probably carcinogenic to humans (24). This review focuses on the Fusarium species that produce fumonisins and the fumonisin analogs produced by each of these species.

FUMONISIN ANALOGS

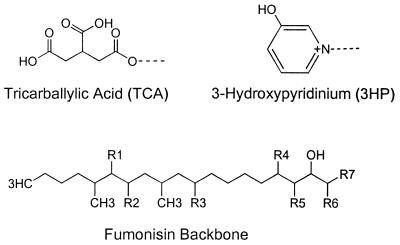

The 28 fumonisin analogs that have been characterized since 1988 can be separated into four main groups, identified as the fumonisin A, B, C, and P series (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The fumonisin B (FB) analogs, comprising toxicologically important FB1, FB2, and FB3, are the most abundant naturally occurring fumonisins, with FB1 predominating and usually being found at the highest levels (36). FB1 typically accounts for 70 to 80% of the total fumonisins produced, while FB2 usually makes up 15 to 25% and FB3 usually makes up from 3 to 8% when cultured on corn or rice or in liquid medium (7, 39, 40). Apart from the FB series, some of the other analogs may occur in naturally contaminated maize at relatively low levels (<5% of the total fumonisins present) (48). These lesser-known fumonisin analogs are not detected with most analytical techniques due to the derivatization process, but they can be detected with the use of liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with electrospray ionization (49).

FIG. 1.

Basic structure of fumonisin (see Table 1 for a list of known fumonisin analogs and the positions of R side chains).

TABLE 1.

Fumonisin analogs

| Analog | Side chains to fumonisin backbonea |

Referenceb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | R7 | ||

| FA1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 6 |

| FA2 | TCA | TCA | H | OH | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 6 |

| FA3 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 49 |

| PHFA3a | TCA | OH | OH | H | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 59 |

| PHFA3b | OH | TCA | OH | H | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 59 |

| HFA3 | OH | OH | OH | H | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 59 |

| FAK1 | O | TCA | OH | OH | H | NHCOCH3 | CH3 | 47 |

| FBK1 | O | TCA | OH | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 49 |

| FB1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 21 |

| Iso-FB1 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | OH | NH2 | CH3 | 31 |

| PHFB1a | TCA | OH | OH | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 68 |

| PHFB1b | OH | TCA | OH | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 68 |

| HFB1 | OH | OH | OH | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 59 |

| FB2 | TCA | TCA | H | OH | H | NH2 | CH3 | 21 |

| FB3 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | H | NH2 | CH3 | 11 |

| FB4 | TCA | TCA | H | H | H | NH2 | CH3 | 11 |

| FB5c | 49 | |||||||

| FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | H | NH2 | H | 8 |

| N-acetyl-FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | H | NHCOCH3 | H | 65 |

| Iso-FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | OH | NH2 | H | 65 |

| N-acetyl-iso-FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | OH | NHCOCH3 | H | 65 |

| OH-FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | OH | NH2 | H | 64 |

| N-acetyl-OH-FC1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | OH | NHCOCH3 | H | 65 |

| FC3 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | H | NH2 | H | 64 |

| FC4 | TCA | TCA | H | H | H | NH2 | H | 58 |

| FP1 | TCA | TCA | OH | OH | H | 3HP | CH3 | 48 |

| FP2 | TCA | TCA | H | OH | H | 3HP | CH3 | 48 |

| FP3 | TCA | TCA | OH | H | H | 3HP | CH3 | 48 |

See Fig. 1 for the structure of the fumonisin backbone and the positions of the R side chains. TCA, tricarballylic acid.

Cited references are the first publications dealing with the analogs in question.

Hexahydroxyalkyl backbone; exact structure unknown at present.

FUMONISIN PRODUCERS

Fifteen Fusarium species have been reported to produce fumonisins (Table 2). Eight of these are in the Section Liseola, i.e., F. verticillioides, mating population A (MP-A) in the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex (6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15, 17, 18, 21, 25, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 45, 46, 48, 49, 50, 57, 58, 62, 68, 70); F. sacchari (Butler) W. Gams MP-B (29); F. fujikuroi Nirenberg MP-C (16); F. proliferatum (Matsushima) Nirenberg MP-D (4, 10, 14, 16, 25, 29, 32, 47, 49, 51, 53, 62, 70, 72); F. subglutinans (Wollenw. et Reinking) Nelson, Toussoun, et Marasas MP-E (29); F. subglutinans sensu lato, isolated from teosinte seed, representing a potentially new biological species within the G. fujikuroi species complex (19); F. thapsinum Klittich, Leslie, Nelson, et Marasas MP-F (26, 30, 45); F. anthophilum (A. Braun) Wollenw. (12, 51); and F. globosum Rheeder, Marasas, et Nelson (69). Another five species fall within the proposed Section Dlaminia (27) (closely related to Section Liseola), i.e., F. nygamai Burgess et Trimboli MP-G (32, 48, 49, 51, 70); F. dlamini Marasas, Nelson, et Toussoun (51); and F. napiforme Marasas, Nelson, et Rabie (51). Trace amounts of fumonisin were detected in culture material of two newly described species, i.e., F. andiyazi Marasas, Rheeder, Lamprecht, Zeller, et Leslie; and F. pseudonygamai Nirenberg et O'Donnell (J. F. Leslie, unpublished data). The remaining two fumonisin-producing Fusarium species are one species in Section Elegans, i.e., F. oxysporum Schlecht. emend. Snyd. et Hans. (2, 64, 65) and one in Section Arthrosporiella, i.e., F. polyphialidicum Marasas, Nelson, Toussoun, et Van Wyk (1). Reports that certain strains of F. oxysporum var. redolens (2) and F. polyphialidicum (1) produce fumonisins need to be confirmed by taxonomic verification of the strains in question as well as by verification of the fumonisins produced.

TABLE 2.

Fumonisin-producing Fusarium species, analogs produced, and the maximum yields of FB1, FB2, and FB3 reported for each species

| Fusarium sp. | Fumonisin analog(s) | Reference(s)a | Maximum fumonisin level (mg kg−1) for: |

Reference(s)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB1 | FB2 | FB3 | ||||

| Section Liseola | ||||||

| F. verticillioides MP-A | FA1-3, FB1-5, iso-FB1, FAK1, FBK1, FC1,4, FP1-3, PH1a-b | 5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 15, 17, 21, 25, 30, 31, 32, 45, 48, 49, 57, 58, 68, 70 | 17,900 | 3,000 | 2,300 | 5, 30, 70 |

| F. sacchari MP-B | FB1 | 29 | 21 | NTc | NT | 29 |

| F. fujikuroi MP-C | FB1 | 16 | 7 | NT | NT | 16 |

| F. proliferatum MP-D | FA1-3, FB1-5, FAK1, FBK1, FC1, FP1-3, PH1a-b | 10, 14, 16, 25, 32, 47, 49, 51, 53, 62, 70 | 31,000 | 17,000 | 5,700 | 10, 53 |

| F. subglutinans MP-E | FB1 | 29 | 150 | NT | NT | 29 |

| F. subglutinans MP-?d | FB1 | 19 | 230 | NT | NT | 19 |

| F. thapsinum MP-F | FB1-3 | 26, 30, 45 | 30 | 5 | 5 | 30 |

| F. anthophilum | FB1-2 | 12, 51 | 610 | 35 | NT | 12, 51 |

| F. globosum | FB1-3 | 69 | 330 | 4 | 24 | 69 |

| Section Dlaminia | ||||||

| F. nygamai MP-G | FA1-3, FB1-5, FAK1, FBK1, FC1, FP1, PH1a-b | 32, 48, 49, 51, 70 | 7,200 | 530 | 140 | 51, 70 |

| F. dlamini | FB1 | 51 | 82 | NT | NT | 51 |

| F. napiforme | FB1 | 51 | 480 | NT | NT | 51 |

| F. pseudonygamai | FB1-2 | 31 | Tre | Tr | NT | 31 |

| F. andiyazi | FB1 | 31 | Tr | NDf | NT | 31 |

| Section Elegans | ||||||

| F. oxysporum | FC1,3-4, N-acetyl-FC1, iso-FC1, N-acetyl-iso-FC1, OH-FC1, N-acetyl-OH-FC1 | 64, 65 | NT | NT | NT | |

| F. oxysporum var. redolens | FB1-3 | 2 | 300 | 6 | 0.9 | 2 |

| Section Arthrosporiella | ||||||

| F. polyphialidicum | FB1 | 1 | 500 | NT | NT | 1 |

References to the analogs produced by each Fusarium species.

References to the maximum FB1, FB2, and FB3 yields in culture. Where more than one reference is cited, the maximum levels for FB1, FB2, and FB3 are summarized from multiple reports.

NT, not tested.

F. subglutinans senso lato. These strains were nonfertile with tester strains of mating populations B, E, and H within the G. fujikuroi species complex (19).

Tr, trace amounts (1 to 4 ng g−1) were detected.

ND, not detected (<1 ng g−1).

The only fungus that does not belong to the genus Fusarium that has been reported to produce fumonisins (FB1, FB2, and FB3) in culture is Alternaria alternata (Fr.) Keissler f. sp. lycopersici (3, 13, 44).

The relative production of FB1, FB2, and FB3 by different Fusarium species is briefly summarized in Table 2. The most important producers of fumonisins are F. verticillioides and F. proliferatum because of their overall high levels of production, wide geographical distribution, frequent occurrence on maize, and association with known animal mycotoxicoses (62, 63). With the exception of F. verticillioides and F. proliferatum, less than 50% of isolates of other fumonisin-producing Fusarium species may produce fumonisins at various levels (51).

NON-FUMONISIN PRODUCERS

Several Fusarium species have been reported as non-fumonisin producers, but in most cases only a few isolates per species have been analyzed. These Fusarium species are F. acuminatum Ell. et Ev. (25, 70); F. annulatum Bugnicourt (51); F. avenaceum (Fr.) Sacc. (70); F. beomiforme Nelson, Toussoun, et Burgess (51); F. camptoceras (Wollenw. et Reinking) emend. Marasas et Logrieco (25, 70); F. circinatum Nirenberg et O'Donnell (= F. subglutinans f. sp. pini) MP-H (19); F. compactum (Wollenw.) Gordon (70); F. concolor Reinking (56); F. crookwellense Burgess, Nelson, et Toussoun (= F. cerealis [Cooke] Sacc.) (56); F. culmorum (W. G. Smith) Sacc. (56); F. decemcellulare Brick (70); F. dimerum Penzig (25); F. equiseti (Corda) Sacc. (25, 70); F. graminearum Schwabe (teleomorph: G. zeae [Schwabe] Petch) (56, 70); F. lateritium Nees (70); F. longipes Wollenw. et Reinking (70); F. poae (Peck) Wollenw. (70); F. pseudograminearum O'Donnell et Aoki (= F. graminearum Group 1) (56, 70); F. reticulatum Mont. (70); F. sambucinum Fuckel (56, 70); F. scirpi Lambotte et Fautr. (70); F. semitectum Berk. et Rav. (= F. pallidoroseum [Cooke] Sacc.) (25, 56, 70); F. solani (Mart.) Appel et Wollenw. emend. Snyder et Hansen (25, 70); F. sporotrichioides Sherb. (70); F. succisae (Schröter) Sacc. (51); and F. tricinctum (Corda) Sacc. (70).

FUMONISIN PRODUCTION BY F. VERTICILLIOIDES

Most isolates of F. verticillioides have the ability to produce fumonisins. Some of the highest FB1 levels produced by this species have been reported with isolates from South Africa (17,900 mg kg−1) (5), China (10,200 mg kg−1) (72), and Argentina (8,160 mg kg−1) (67). Although a few F. verticillioides isolates from Nepal (50) do not produce any fumonisin, other isolates from the same region have been reported to produce FB1 at levels of up to 6,400 mg kg−1 (16, 50). Several isolates of this species from Southeast Asia (42) produce fumonisins at low levels, with a maximum of 147 mg kg−1, whereas some isolates from Australia (50) produced only trace quantities of FB1.

F. verticillioides strain MRC 826 (= FRC M-1325, accession number at the Fusarium Research Center, Pennsylvania State University, Pa.), which was isolated in 1975 from maize in an area of high incidence of human esophageal cancer in the Transkei region of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (33), and from which the fumonisins were first isolated and characterized (21), has been used to produce fumonisins in numerous studies all over the world. “It has been the most thoroughly studied strain of F. moniliforme and consequently much of our knowledge of F. moniliforme toxicity is attributable to experiments using MRC 826 as a model” (71).

The highest yield of FB1 (17,900 mg kg−1) by F. verticillioides was obtained from whole maize kernels as culture material, with F. verticillioides MRC 826 as inoculum, incubated at 20°C in the dark for 13 weeks (5). The highest yield of FB1 that has been reported for a Fusarium species was obtained with a maize isolate of F. proliferatum (no accession number given) from Spain cultured on whole maize (31,000 mg kg−1) (10). This isolate also produced the highest published yield of FB2 (17,000 mg kg−1). F. proliferatum M-6284, cultured on whole yellow maize, produced the highest reported yield of FB3 (5,700 mg kg−1) (53).

CONCLUSION

Numerous studies have provided valuable data on the toxicology of purified fumonisins of the FB series, yet the search continues for other toxic fumonisin analogs which may also pose a health risk to humans and animals. Maize and maize-based products have been the main focus of fumonisin research due to the widespread contamination of this food source by relatively high levels of FB1, FB2, and FB3. As additional and new Fusarium species with various fumonisin-producing capabilities are described from other agriculturally important crops, such as sorghum (38) and millet (54), it becomes necessary to determine whether fumonisins also occur in these crops and, if so, to determine which analogs occur and at what levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank past and present staff members of the PROMEC Unit and our South African and international collaborators.

We thank the Medical Research Council of South Africa for their continued financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas, H. K., and C. M. Ocamb. 1995. First report of production of fumonisin B1 by Fusarium polyphialicum collected from seeds of Pinus strobus. Plant Dis. 79:642. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbas, H. K., C. M. Ocamb, W. Xie, C. J. Mirocha, and W. T. Shier. 1995. First report of fumonisin B1, B2 and B3 production by Fusarium oxysporum var. redolens. Plant Dis. 79:968. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbas, H. K., and R. T. Riley. 1996. The presence and phytotoxicity of fumonisins and AAL-toxin in Alternaria alternata. Toxicon 34:133-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abbas, H. K., R. D. Cartwright, W. Xie, C. J. Mirocha, J. L. Richard, T. J. Dvorak, G. L. Sciumbato, and W. T. Shier. 1999. Mycotoxin production by Fusarium proliferatum isolates from rice with Fusarium sheath rot disease. Mycopathologia 147:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alberts, J. F., W. C. A. Gelderblom, P. G. Thiel, W. F. O. Marasas, D. J. Van Schalkwyk, and Y. Behrend. 1990. Effects of temperature and incubation period on the production of fumonisin B1 by Fusarium moniliforme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:1729-1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bezuidenhout, S. C., W. C. A. Gelderblom, C. P. Gorst-Allman, R. M. Horak, W. F. O. Marasas, G. Spiteller, and R. Vleggaar. 1988. Structure elucidation of the fumonisins, mycotoxins from Fusarium moniliforme. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1988:743-745. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Branham, B. E., and R. D. Plattner. 1993. Alanine is a precursor in the biosynthesis of fumonisin B1 by Fusarium moniliforme. Mycopathologia 124:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Branham, B. E., and R. D. Plattner. 1993. Isolation and characterization of a new fumonisin from liquid cultures of Fusarium moniliforme. J. Nat. Prod. 56:1630-1633. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabañes, F. J., M. L. Abarca, M. R. Bragulat, and G. Castellá. 1993. High incidence of fumonisin-producing strains of Fusarium moniliforme isolated in Spain, p. 293-296. In K. A. Scudamore (ed.), Occurrence and significance of mycotoxins. Central Science Laboratory, Slough, United Kingdom.

- 10.Castellá, G., M. R. Bragulat, and F. J. Cabañes. 1999. Fumonisin production by Fusarium species isolated from cereals and feeds in Spain. J. Food Prot. 62:811-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cawood, M. E., W. C. A. Gelderblom, R. Vleggaar, Y. Behrend, P. G. Thiel, and W. F. O. Marasas. 1991. Isolation of the fumonisin mycotoxins—a quantitative approach. J. Agric. Food Chem. 39:1958-1962. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chelkowski, J., and H. Lew. 1992. Fusarium species of Liseola Section—occurrence in cereals and ability to produce fumonisins. Microbiologie Aliments Nutr. 10:49-53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen, J. P., C. J. Mirocha, W. Xie, L. Hogge, and D. Olson. 1992. Production of the mycotoxin fumonisin B1 by Alternaria alternata f. sp. lycopersici. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3928-3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chulze, S. N., M. L. Ramirez, M. Pascale, and A. Visconti. 1998. Fumonisin production by and mating populations of Fusarium section Liseola isolates from maize in Argentina. Mycol. Res. 102:141-144. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desjardins, A. E., R. D. Plattner, and P. E. Nelson. 1994. Fumonisin production and other traits of Fusarium moniliforme strains from maize in northeast Mexico. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1695-1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desjardins, A. E., H. K. Manandhar, R. D. Plattner, G. G. Manandhar, S. M. Poling, and C. M. Maragos. 2000. Fusarium species from Nepalese rice and production of mycotoxins and gibberellic acid by selected species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1020-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desjardins, A. E., G. Manandhar, R. D. Plattner, C. M. Maragos, K. Shrestha, and S. P. McCormick. 2000. Occurrence of Fusarium species and mycotoxins in Nepalese maize and wheat and the effect of traditional processing methods on mycotoxin levels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48:1377-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desjardins, A. E., and R. D. Plattner. 2000. Fumonisin B1-nonproducing strains of Fusarium verticillioides cause maize (Zea mays) ear infection and ear rot. J. Agric. Food Chem. 48:5773-5780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desjardins, A. E., R. D. Plattner, and T. R. Gordon. 2000. Gibberella fujikuroi mating population A and Fusarium subglutinans from teosinte species and maize from Mexico and Central America. Mycol. Res. 104:865-872. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dutton, M. F. 1996. Fumonisins, mycotoxins of increasing importance: their nature and their effects. Pharmacol. Ther. 70:137-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gelderblom, W. C. A., K. Jaskiewicz, W. F. O. Marasas, P. G. Thiel, M. J. Horak, R. Vleggaar, and N. P. J. Kriek. 1988. Fumonisins—novel mycotoxins with cancer promoting activity produced by Fusarium moniliforme. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1806-1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelderblom, W. C. A., W. F. O. Marasas, R. Vleggaar, P. G. Thiel, and M. E. Cawood. 1992. Fumonisins: isolation, chemical characterization and biological effects. Mycopathologia 117:11-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelderblom, W. C. A., S. D. Snyman, S. Abel, S. Lebepe-Mazur, C. M. Smuts, L. Van der Westhuizen, W. F. O. Marasas, T. C. Victor, S. Knasmüller, and W. Huber. 1996. Hepatotoxicity and carcinogenicity of the fumonisins in rats. A review regarding mechanistic implications for establishing risk in humans, p. 279-296. In L. S. Jackson, J. W. DeVries, and L. B. Bullerman (ed.), Fumonisins in food. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y. [PubMed]

- 24.International Agency for Research on Cancer. 1993. Toxins derived from Fusarium moniliforme: fumonisins B1 and B2 and Fusarin C, p. 445-466. In IARC Monographs on the evaluation of the carcinogenic risks to humans: some naturally occurring substances: food items and constituents, heterocyclic aromatic amines and mycotoxins, vol. 56. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Jimenez, M. T., T. Huerta, and R. Mateo. 1997. Mycotoxin production by Fusarium species isolated from bananas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:364-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klittich, C. J. R., J. F. Leslie, P. E. Nelson, and W. F. O. Marasas. 1997. Fusarium thapsinum (Gibberella thapsina): a new species in section Liseola from sorghum. Mycologia 89:643-652. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwasna, H., J. Chelkowski, and P. Zajkowski. 1991. Flora Polska, vol. 22. Grzyby (Mycota). Polska Akademia Nauk, Instytut Botaniki, Warsaw, Poland.

- 28.Leslie, J. F., F. J. Doe, R. D. Plattner, D. D. Shackelford, and J. Jonz. 1992. Fumonisin B1 production and vegetative compatibility of strains from Gibberella fujikuroi mating population ‘A' (Fusarium moniliforme). Mycopathologia 117:37-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leslie, J. F., R. D. Plattner, A. E. Desjardins, and C. J. R. Klittich. 1992. Fumonisin B1 production by strains from different mating populations of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium Section Liseola). Phytopathology 82:341-345. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leslie, J. F., W. F. O. Marasas, G. S. Shephard, E. W. Sydenham, S. Stockenström, and P. G. Thiel. 1996. Duckling toxicity and the production of fumonisin and moniliformin by isolates in the A and F mating populations of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium moniliforme). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:1182-1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacKenzie, S. E., M. E. Savard, B. A. Blackwell, J. D. Miller, and J. W. ApSimon. 1998. Isolation of a new fumonisin from Fusarium moniliforme grown in liquid culture. J. Nat. Prod. 61:367-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnoli, C. E., M. A. Saenz, S. M. Chiacchiera, and A. M. Dalcero. 1999. Natural occurrence of Fusarium species and fumonisin-production by toxigenic strains from poultry feeds in Argentina. Mycopathologia 145:35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marasas, W. F. O., P. E. Nelson, and T. A. Toussoun. 1984. Toxigenic Fusarium species. Identity and mycotoxicology. Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, Pa.

- 34.Marasas, W. F. O., T. S. Kellerman, W. C. A. Gelderblom, J. A. W. Coetzer, P. G. Thiel, and J. J. Van der Lugt. 1988. Leukoencephalomalacia in a horse induced by fumonisin B1 isolated from Fusarium moniliforme. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 55:197-203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marasas, W. F. O. 1995. Fumonisins: their implications for human and animal health. Nat. Toxins 3:93-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marasas, W. F. O. 1996. Fumonisins: history, worldwide occurrence and impact, p. 1-17. In L. S. Jackson, J. W. DeVries, and L. B. Bullerman (ed.), Fumonisins in food. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 37.Marasas, W. F. O. 1997. Risk assessment of fumonisins produced by Fusarium moniliforme in corn. Proceedings of the Fifth European Fusarium Seminar, Szeged, Hungary. Cereal Res. Comm. 25:399-406. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marasas, W. F. O., J. P. Rheeder, S. C. Lamprecht, K. A. Zeller, and J. F. Leslie. 2001. Fusarium andiyazi sp. nov., a new species from sorghum. Mycologia 93:1203-1210. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marín, S., V. Sanchis, and N. Magan. 1995. Water activity, temperature, and pH effects on growth of Fusarium moniliforme and Fusarium proliferatum isolates from maize. Can. J. Microbiol. 41:1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marín, S., V. Sanchis, I. Vinas, R. Canela, and N. Magan. 1995. Effect of water activity and temperature on growth and fumonisin B1 and B2 production by Fusarium proliferatum and F. moniliforme in grain. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 21:298-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merrill, A. H., E. Wang, D. G. Gilchrist, and R. T. Riley. 1993. Fumonisins and other inhibitors of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis. Adv. Lipid Res. 26:215-234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miller, J. D., M. E. Savard, A. Sibilia, S. Rapior, A. D. Hocking, and J. J. Pitt. 1993. Production of fumonisins and fusarins by Fusarium moniliforme from Southeast Asia. Mycologia 85:385-391. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller, J. D. 1995. Fungi and mycotoxins in grain: implications for stored product research. J. Stored Prod. Res. 31:1-16. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mirocha, C. J., T. Chen, W. Xie, Y. Xu, H. K. Abbas, and L. R. Hogge. 1996. Biosynthesis of fumonisin and AAL derivatives by Alternaria and Fusarium in laboratory culture. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 392:213-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moretti, A., G. A. Bennett, A. Logrieco, A. Bottalico, and M. N. Beremand. 1995. Fertility of Fusarium moniliforme from maize and sorghum related to fumonisin production in Italy. Mycopathologia 131:25-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munkvold, G. P., and A. E. Desjardins. 1997. Fumonisins in maize. Can we reduce their occurrence? Plant Dis. 81:556-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Musser, S. M., R. M. Eppley, and E. P. Mazzola. 1995. Identification of an n-acetyl keto derivative of fumonisin B1 in corn cultures of Fusarium proliferatum. J. Nat. Prod. 58:1392-1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Musser, S. M., M. L. Gay, and E. P. Mazzola. 1996. Identification of a new series of fumonisins containing 3-hydroxypyridine. J. Nat. Prod. 59:970-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musser, S. M., and R. D. Plattner. 1997. Fumonisin composition in cultures of Fusarium moniliforme, Fusarium proliferatum, and Fusarium nygamai. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45:1169-1173. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson, P. E., R. D. Plattner, D. D. Shackelford, and A. E. Desjardins. 1991. Production of fumonisins by Fusarium moniliforme strains from various substrates and geographic areas. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2410-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nelson, P. E., R. D. Plattner, D. D. Shackelford, and A. E. Desjardins. 1992. Fumonisin B1 production by Fusarium species other than F. moniliforme in Section Liseola and by some related species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:984-989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nelson, P. E., A. E. Desjardins, and R. D. Plattner. 1993. Fumonisins, mycotoxins produced by Fusarium species: biology, chemistry and significance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 31:233-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nelson, P. E., J. H. Juba, P. F. Ross, and L. G. Rice. 1994. Fumonisin production by Fusarium species on solid substrates. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 77:522-524. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nirenberg, H. I., and K. O'Donnell. 1998. New Fusarium species and combinations within the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 90:434-458. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Norred, W. P. 1993. Fumonisins—mycotoxins produced by Fusarium moniliforme. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health 38:309-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norred, W. P., C. W. Bacon, R. T. Riley, K. A. Voss, and F. I. Meredith. 1999. Screening of fungal species for fumonisin production and fumonisin-like disruption of sphingolipid biosynthesis. Mycopathologia 146:91-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Plattner, R. D., D. Weisleder, D. D. Shackelford, R. Peterson, and R. G. Powell. 1992. A new fumonisin from solid cultures of Fusarium moniliforme. Mycopathologia 117:23-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Plattner, R. D. 1995. Detection of fumonisins produced in Fusarium moniliforme cultures by HPLC with electrospray MS and evaporative light scattering detectors. Nat. Toxins 3:294-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poling, S. M., and R. D. Plattner. 1999. Rapid purification of fumonisins and their hydrolysis products with solid-phase extraction columns. J. Agric. Food Chem. 47:2344-2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Riley, R. T., W. P. Norred, and C. W. Bacon. 1993. Fungal toxins in foods: recent concerns. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 13:167-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Riley, R. T., K. A. Voss, W. P. Norred, R. P. Sharma, E. Wang, and A. H. Merrill. 1998. Fumonisins: mechanism of mycotoxicity. Rev. Méd. Vét. 149:617-626. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ross, P. F., P. E. Nelson, J. L. Richard, G. D. Osweiler, L. G. Rice, R. D. Plattner, and T. M. Wilson. 1990. Production of fumonisins by Fusarium moniliforme and Fusarium proliferatum isolates associated with equine leukoencephalomalacia and pulmonary edema syndrome in swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56:3225-3226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ross, P. F., R. G. Rice, G. D. Osweiler, P. E. Nelson, J. L. Richard, and T. M. Wilson. 1992. A review and update of animal toxicoses associated with fumonisin-contaminated feeds and production of fumonisins by Fusarium isolates. Mycopathologia 117:109-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seo, J.-A., J.-C. Kim, and Y.-W. Lee. 1996. Isolation and characterization of two new type C fumonisins produced by Fusarium oxysporum. J. Nat. Prod. 59:1003-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Seo, J.-A., J.-C. Kim, and Y.-W. Lee. 1999. N-acetyl derivatives of type C fumonisins produced by Fusarium oxysporum. J. Nat. Prod. 62:355-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shephard, G. S., P. G. Thiel, S. Stockenström, and E. W. Sydenham. 1996. Worldwide survey of fumonisin contamination of foods and feeds. J. Assoc. Off. Anal. Chem. 79:671-687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sydenham, E. W., G. S. Shephard, P. G. Thiel, W. F. O. Marasas, J. P. Rheeder, C. E. Peralta Sanhueza, H. H. L. Gonzalez, and S. L. Resnik. 1993. Fumonisins in Argentinian field trial corn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 41:891-895. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sydenham, E. W., P. G. Thiel, G. S. Shephard, K. R. Koch, and T. Hutton. 1995. Preparation and isolation of the partially hydrolysed moiety of fumonisin B1. J. Agric. Food Chem. 43:2400-2405. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sydenham, E. W., G. S. Shephard, S. Stockenström, J. P. Rheeder, W. F. O. Marasas, and M. J. Van der Merwe. 1997. Production of fumonisin B analogues and related compounds by Fusarium globosum, a newly described species from corn. J. Agric. Food Chem. 45:4004-4010. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Thiel, P. G., W. F. O. Marasas, E. W. Sydenham, G. S. Shephard, W. C. A. Gelderblom, and J. J. Nieuwenhuis. 1991. Survey of fumonisin production by Fusarium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:1089-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Voss, K. A. 1990. Toxins from Fusarium moniliforme, a common fungus in corn. Vet. Hum. Toxicol. 32(Suppl.):57-63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yoshizawa, T., A. Yamashita, and Y. Luo. 1994. Fumonisin occurrence in corn from high- and low-risk areas for human esophageal cancer in China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1626-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]