A BRAVE NEW WORLD FOR MEDICINE

Much has been written about the human genome project and its potential effects on medicine,1 particularly primary care and family practice,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 and on society as a whole.10 Many believe it will bring a major transformation in the dominant paradigm of contemporary medicine: “Perhaps the most important single contribution of the new genetics to health care is that it will create a biological rather than a phenotype framework with which to categorize diseases.”11

This paradigm shift will lead to disease being redefined in terms of biological or biochemical events. Hopefully, this redefinition in turn will help physicians render diagnoses and, ultimately, treat patients using gene therapy. New drugs will be developed, and available drugs will be better targeted to a patient's specific genetic profile.

Although there are ethical concerns about how genetic information might be used to determine insurability and employment and to make reproductive decisions, the general feeling is that the human genome project represents a brave new world for medicine. The project has enjoyed good press coverage and favorable reporting, including considerable exaggeration of its scientific achievements. Even among medical practitioners, the response has largely been enthusiastic despite the obviously inadequate training physicians have in genetics12 and some misunderstanding of what preventive role genetic medicine can play.13

THE LIMITATIONS OF GENOMIC MEDICINE

Despite the achievements of genomic medicine, evidence of its limitations is accumulating. Already the hope for what one writer has called “O-GOD”10—that there would be one-gene-one-disease—has been dashed. For example, the identified genes for breast cancer account for only 10% of cases. Except when a disease is the expression of a single gene, genetic understanding of disease may prove to be extremely complex. And there is no certainty that genetic knowledge will give rise to genetic therapies that are effective, practical, and affordable. Perhaps the most negative effect of the human genome project might come in its diversion of resources, scientists, and physicians from other promising paradigms. To understand how genomic medicine might be a diversion, it is useful to place its development in the broader history of medicine.

REDUCTIONISM VERSUS HOLISM

Medicine has historically been affected by two contrary philosophies given to us by the ancient Greeks.14 The Aesculapian philosophy had a mechanistic view of health and disease and adopted the natural sciences as the model for medicine. The focus was on the disease and its causes and on seeking a cure through the science of medicine. In contrast, the Hygeian philosophy focused on the person and on the inherent health-maintaining and health-restoring abilities within the person as the source of recovery and health. These same two philosophies resonate in contemporary medicine in the debate between reductionism and holism.

Beginning in the 16th century with the introduction of clinical anatomy as the basis of linking lesions to symptoms, medicine established the clinico-pathologic correlation. Anatomic dissection was used to investigate disease, and surgical intervention was integral to treating disease.15 With the development of cellular pathologic analysis, the focus moved from organs to cells, and the microscope became the investigative tool. The success of these approaches gave medicine a mechanistic and structural theory of disease in which disease is located in cells or organs.

A consistency in this mechanistic paradigm runs through the history of cellular and molecular biology. With the germ theory of disease, this medical paradigm became the dominant one in the 20th century. Biomedicine, as both a research and a treatment paradigm, continues to be successful.

A PARADIGM CRISIS

The paradigm, of course, was never without its critics. Beginning in the 1960s, a time of social and cultural upheaval, and continuing through the last part of the 20th century, a “paradigm crisis” occurred in which biomedicine has been the focus of numerous critiques.16,17,18 These critiques were both political, as in the feminist and sociologic critiques on professional dominance by physicians, and intellectual, as in the humanist critique of medicine. They led to a re-evaluation of the contribution of medicine to the health of the population; a challenge to the influence of medicine on the health system; an increase in consumer activism around health issues; and by the latter part of the century, a massive restructuring of the financing of health care. At the same time, the chronic illnesses and the so-called lifestyle diseases, such as cancer and cardiovascular illness, became the dominant illnesses and were resisting the best efforts of biomedicine to find cures.

RESPONSES TO REDUCTIONISM

At least four trends in medicine arose from the paradigm crisis. The first was the re-emergence of a holistic paradigm with the establishment of the American Holistic Medical Association in 1978. Several major spokespersons for this paradigm emerged,18,19 but the best known was author and essayist Norman Cousins.20

A second paradigm was Engel's biopsychosocial paradigm.21 Many writers took this paradigm as a new agenda for medicine,22 and it clearly has affected medical education. Engel's paradigm is one of the dominant theoretical paradigms used in medical education.

A third response was phenomenology in which illness is seen not as a dysfunction of the physical body, but as a disruption of the lived body, a disorganization of the patient's self.17,23 In phenomenology, medicine should involve the patients' understanding and experience of their illness. Biomedicine “omits the person to whom the body belongs, the person whose body it is.”24

A fourth response is that of humanistic medicine. Here, the focus is on the values in medicine and on changing them. Biomedicine is seen as introducing dehumanizing concepts and behaviors through both technology and its institutions. The appeal in this paradigm is for a more personal and humanistic approach to patients. This paradigm underlies the major recommendations of the report Physicians for the 21st Century.25

It is clear that by the late 20th century, medicine was in a lively debate that focused on the limitations of the biomedical paradigm. Other sciences, such as epidemiology, were providing an alternative basis for clinical practice and education. In the midst of this was the call for a new social contract between medicine and society, with population medicine recommended as a way of renewing that contract.26

Although these intellectual developments had begun to influence medical education and practice, they demanded a different type of research paradigm that would address cultural, social, and psychological aspects of health and the health encounter. The developments were particularly amenable to qualitative research. Demands for this type of research began to appear in medical journals27,28 along with articles on how to conduct it29 and how to evaluate it.30

The end of the 20th century, therefore, saw an expanding critique of medicine, a weakening of medical dominance in the field of health, and a rejection of biomedicine by the public in favor of alternative therapies.31 These movements share a dissatisfaction with biomedicine and a feeling that its reductionism and emphasis on technology have diminished both medicine and the patient and resulted in uncontrollable costs.

A key component of the debate has been a crisis in primary care,32 which at least one author suggests has been complicated by the demand for more humanistic and compassionate medical care and is a reaction against scientific, technologic, and bureaucratic care.33 The solution to the ills of biomedicine has invariably been seen as lying within primary care itself—with primary care as the focus of a new type of medical practice.

GENOMIC MEDICINE: A RETURN TO REDUCTIONISM

In the rapidly expanding literature on genomic medicine, it is as if a critique of biomedicine never occurred. Genomic medicine is almost a perfect representation of the “sorcerer's broom” in action. Cassell suggested that medicine's love for technology can be found in five sources: wonder and wonderment, the lure of the immediate, unambiguous values, the avoidance of uncertainty, and the human desire for power.34 Genomic medicine runs the risk of diverting the attention of medicine away from what the public and its critics have been trying to tell it at the very moment when it seemed as if medicine was adopting a more holistic paradigm.

If history teaches anything, it is that such distractions can be costly for medicine. Physicians' preoccupation with the “perils” of a national health care system blinded them to a greater threat to medical autonomy: the transformation of the marketplace by the private sector and the emergence of managed care. The seduction of genomic medicine might also blind the profession to the message that medicine is about people, not genes.

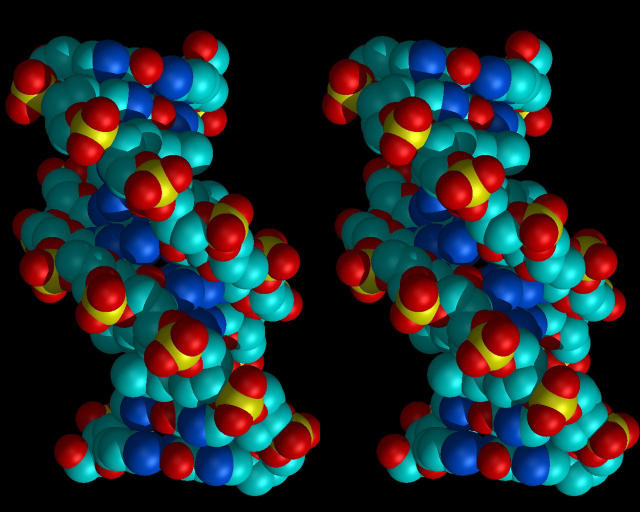

Figure 1.

The brave new world of genomics: will this new technology hurt or help health care practice?

Figure 2.

There is no certainty that genetic knowledge will give rise to genetic therapies

Competing interests: None declared

References

- 1.Fulginiti VA. Genetics: the quiet revolution in science and medicine. Implications for research on child health issues, education of health professionals, and the new preventive and curative medicine. Am J Dis Child 1993;147: 1139-1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whittaker LA. The implications of the Human Genome Project for family practice. J Fam Pract 1992;35: 294-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van McCrary S, Allen B, Moseley R, et al. Ethical and practical implications of the human genome initiative for family medicine. Arch Fam Med 1993;2: 1158-1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holtzman NA. Primary care physicians as providers of frontline genetic services. Fetal Diagn Ther 1993;8: S213-S219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qureshi N, Raeburn JA. Clinical genetics meets primary care. BMJ 1993;307: 816-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doukas DJ. Primary care and the human genome project: into the breach. Arch Fam Med 1993;2: 1179-1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watson EK, Shickle D, Qureshi N, Emery J, Austoker J. The “new genetics” and primary care: GPs' views on their role and their educational needs. Fam Pract 1999;16: 420-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emery J, Watson E, Rose P, Andermann A. A systematic review of the literature exploring the role of primary care in genetic services. Fam Pract 1999;16: 426-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ball BG, Anderson WF. MSJAMA: Bringing gene therapy to the clinic. JAMA 2000;284: 2788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conrad P, Gabe J. Sociological perspectives on the new genetics: an overview. Sociol Health Illness 1999;21: 505-516. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell J. The new genetics in clinical practice. BMJ 1998;316: 618-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caulfield T. Gene testing in the biotech century: are physicians ready? CMAJ 1999;161: 1122-1124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juengst ET. “Prevention” and the goals of genetic medicine. Hum Gene Ther 1995;6: 1595-1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beckman JF, Fernandez CE, Coulter ID. A systems model of health care: a proposal. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1996;19: 208-215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiser SJ. Environmental versus biological causation in medicine. In: Cassell EJ, Siegler M, eds. Changing Values in Medicine. Frederick, MD: University Publications of America; 1979: 197-201.

- 16.Cassell EJ, Siegler M, eds. Changing Values in Medicine. Frederick, MD: University Publications of America; 1979.

- 17.McWhinney IR. Are we on the brink of a major transformation of clinical method? CMAJ 1986;135: 873-878. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon JS. The paradigm of holistic medicine. In: Hastings AC, Fadiman J, Gordon JS, eds. Health for the Whole Person. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1980: 3-35.

- 19.Capra F. Wholeness and health. Holistic Med 1986;1: 145-159. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cousins N. The holistic health explosion. Saturday Rev March 31, 1979: 17-19. [PubMed]

- 21.Engel JM. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Holistic Med 1989;4: 37-53. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cluff LE. New agenda for medicine. Am J Med 1987;82: 803-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellegrino ED. Medicine, science, art: an old controversy revisited. Man Med 1979;4: 43-52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toombs SK. Illness and the paradigm of the lived body. Theor Med 1988;9: 201-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. Physicians for the Twenty-First Century. Washington, DC: AAMC; 1984. Report of the Panel on the General Professional Education of the Physician (GPEP) and College Preparation for Medicine. [PubMed]

- 26.Coulter ID, Wilkes M. Medical schools, the social contract and population medicine: McMaster revisited. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 1995;18: 554-558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ 1995;311: 42-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inui TS. The virtue of qualitative and quantitative research. Ann Intern Med 1996;125: 770-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harding G, Gantley M. Qualitative methods: beyond the cookbook. Fam Pract 1998;15: 76-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inui TS, Frankel RM. Evaluating the quality of qualitative research: a proposal pro tem. J Gen Intern Med 1991;6: 485-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990-1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA 1998;280: 1569-1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Terris M. Issues in primary care: false starts and lesser alternatives. Bull N Y Acad Med 1977;53: 129-140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graner J. The primary care crisis: the contribution of anti-scientism. Am J Med 1986;81: 330-331. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cassell EJ. The sorcerer's broom: medicine's rampant technology. Hastings Cent Rep 1993;23: 32-39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]