Abstract

To understand the gene network controlling tolerance to cold stress, we performed an Arabidopsis thaliana genome transcript expression profile using Affymetrix GeneChips that contain ∼24,000 genes. We statistically determined 939 cold-regulated genes with 655 upregulated and 284 downregulated. A large number of early cold-responsive genes encode transcription factors that likely control late-responsive genes, suggesting a multitude of transcriptional cascades. In addition, many genes involved in chromatin level and posttranscriptional regulation were also cold regulated, suggesting their involvement in cold-responsive gene regulation. A number of genes important for the biosynthesis or signaling of plant hormones, such as abscisic acid, gibberellic acid, and auxin, are regulated by cold stress, which is of potential importance in coordinating cold tolerance with growth and development. We compared the cold-responsive transcriptomes of the wild type and inducer of CBF expression 1 (ice1), a mutant defective in an upstream transcription factor required for chilling and freezing tolerance. The transcript levels of many cold-responsive genes were altered in the ice1 mutant not only during cold stress but also before cold treatments. Our study provides a global picture of the Arabidopsis cold-responsive transcriptome and its control by ICE1 and will be valuable for understanding gene regulation under cold stress and the molecular mechanisms of cold tolerance.

INTRODUCTION

Low temperature is one of the major environmental stresses that many plants have to cope with during their life cycle. Plants from temperate regions have the capacity to cold acclimate, that is, to develop increased freezing tolerance after being exposed to low nonfreezing temperatures (Guy, 1990). Many physiological and molecular changes occur during cold acclimation (Thomashow, 1999). Among them, the transcriptional activation or repression of genes by low temperature is of primary importance (Thomashow, 1999). Early studies have identified a number of genes in plants that change expression under cold stress (Thomashow, 1994, 1999). A subset of the cold-responsive genes have in their promoters the dehydration-responsive element (DRE; 5′-TACCGACAT-3′)/C-repeat (CRT; 5′-TGGCCGAC-3′) with the common core motif (5′-CCGAC-3′). Transcriptional activators (DEHYDRATION-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR 1/C-REPEAT BINDING FACTOR [DREB1/CBF]) that are capable of binding to DRE/CRT have been isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana using the yeast one-hybrid approach (Stockinger et al., 1997). Three members of the CBF gene family are rapidly and transiently induced by cold stress (Gilmour et al., 1998; Medina et al., 1999). Ectopic expression of CBF1/3 (DREB1B/A) activated the expression of genes with the DRE/CRT promoter element at warm temperatures, which resulted in constitutive freezing tolerance (Stockinger et al., 1997; Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998; Shinwari et al., 1998; Kasuga et al., 1999). Interestingly, Arabidopsis mutants with loss-of-function in CBF2/DREB1C show enhanced cold induction of CBF/DREB1 target genes and increased freezing tolerance, suggesting a complex interplay among the CBF/DREB1 family members and possibly also with other transcription factors (Novillo et al., 2004).

Recently, a constitutive transcription factor, INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION 1 (ICE1), which acts upstream of the CBFs in the cold-response pathway, was identified (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). ICE1 binds to the CBF3 promoter and may activate CBF3 expression upon cold treatment. The dominant ice1 mutation blocks the cold induction of CBF3 but not CBF1 or CBF2 (Chinnusamy et al., 2003).

The completion of the Arabidopsis genome sequence and technical advances in microarray analysis have allowed for the study of gene expression on a large scale. Several studies have used cDNA microarrays or Affymetrix GeneChips to identify cold-responsive genes in Arabidopsis (Seki et al., 2001, 2002; Fowler and Thomashow, 2002; Kreps et al., 2002). Expression profiling studies have also been performed with mutant plants or plants that overexpress a certain regulatory gene to understand the role of the genes in cold-responsive gene expression (Fowler and Thomashow, 2002; Goda et al., 2002; Osakabe et al., 2002). However, the microarrays or GeneChips used in these studies contained no more than one-third of the Arabidopsis genome, and much of the Arabidopsis genome has not been statistically examined for transcript responses to cold stress.

In this study, we used the Affymetrix Arabidopsis 24K GeneChip representing ∼24,000 genes to profile gene expression under cold stress. We identified 655 genes that are statistically cold upregulated and 284 genes that are downregulated. Our results suggest that cold stress triggers a multitude of transcriptional cascades because many of the early cold-responsive genes encode transcription factors that likely activate the genes induced late in the cold response. A number of genes important for the biosynthesis or signaling of plant hormones, such as abscisic acid, gibberellic acid, and auxin, are regulated by cold stress. The regulation of these genes might be important in coordinating cold tolerance with growth and development. We also determined the transcript profiles and their responses to cold stress in the ice1 mutant. The ice1 mutation affects the cold induction of a large number of genes, including many transcription factors. In addition, the ice1 mutation alters the basal transcript levels of many cold-responsive genes. Our study provides a broad picture of the Arabidopsis cold-responsive transcriptome and its control by ICE1.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Cold-Regulated Genes in Arabidopsis

We used the Affymetrix Arabidopsis ATH1 genome GeneChip, which contains >22,500 probe sets representing ∼24,000 genes, to identify cold-regulated genes in Arabidopsis. Total RNA was prepared from Arabidopsis seedlings after 0, 3, 6, or 24 h cold treatment at 0°C. The 3- and 6-h time points were chosen to capture early responsive genes, and the 24-h point for late-responsive genes. A total of 100 to 150 seedlings from three plates was used to create pools of RNA used at each time point. As each plate can hold >300 plants, half of each plate contained the wild type and the other ice1 seedlings. Thus, at each time point, the three plates produced one wild-type pool and one ice1 pool of RNA. This procedure was repeated at each time point to produce a total of two biologically independent pools of RNA at each time point. The wild-type Arabidopsis used had a CBF3 promoter-driven luciferase transgene, the background line of the ice1 mutant (Chinnusamy et al., 2003).

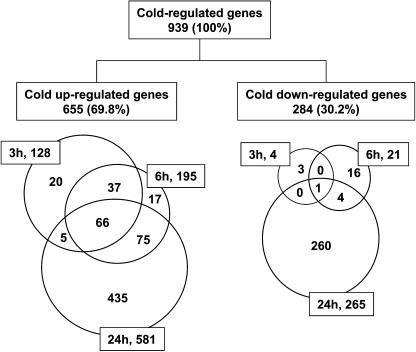

To determine cold-regulated genes in Arabidopsis, we performed statistical analyses of the GeneChip data. Signal intensity data were first obtained by the Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 program, where each cell signal intensity was background subtracted, weighted using one-step Tukey's biweight algorithm, averaged, and scaled to a globally normalized intensity of 500 (the manufacturer-suggested arbitrary value) for each chip. For statistical analysis, the signal intensity data were then analyzed with use of a two-stage linear statistical model and robust test statistics with the statistical package R (R Development Core Team, 2003; http://www.R-project.org) and the Limma package (Smyth, 2005). The 10,000 bootstrap simulations (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) were used to obtain nonparametric P values for testing a null hypothesis of no difference for gene-specific contrasts of expression levels between the different time points (see Methods for details). False discovery rates (FDRs) for various P value thresholds were later determined by the method of Benjamini and Yekutieli (2001) on the observed distribution of P values. Genes with <1% of FDR at any time point were considered significantly cold responsive. When this threshold was applied, 939 genes were determined to be cold regulated with 655 upregulated and 284 downregulated (Figure 1). Thus, ∼3.9% of all Arabidopsis genes were determined to be cold responsive.

Figure 1.

Venn Diagrams of Cold-Regulated Genes.

Percentages in parentheses were calculated with the total numbers of cold-regulated genes (939). Figures in rectangles indicate cold treatment hours (h) and total number of cold-regulated genes at each time point.

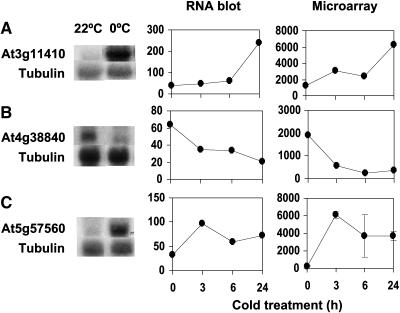

To validate the microarray data, we performed RNA gel blot analysis for three cold-regulated genes from our list. These included a protein phosphatase 2C (At3g11410), a small auxin upregulated RNA (SAUR) gene (At4g38840), and TOUCH4 (At5g57560). The RNA gel blot results showed that the three genes are all cold regulated, and their expression kinetics from the RNA gel blots is very similar to those obtained from microarray analysis (Figure 2). These results support the validity of the Arabidopsis cold-regulated transcriptome from the GeneChip analysis.

Figure 2.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of Cold-Regulated Genes Selected from Microarray Analysis.

Cold-responsive genes were tested by RNA gel blot analysis. For expression pattern comparisons, each corresponding gene transcript level was plotted using intensities from RNA gel blots and microarrays. The x axis shows time points during cold treatment (0°C), and y axis shows signal intensities in arbitrary units. Gene names and treatments for RNA gel blot pictures: (A) At3g11410 (protein phosphatase 2C, 0°C 24 h), (B) At4g38840 (SAUR, 0°C 6 h), and (C) At5g57560 (TCH4, 0°C 3 h). Tubulin was used as a loading control.

Among the 655 cold upregulated genes, 128 were upregulated at 3 h, 195 at 6 h, and 581 at 24 h of cold treatment. Thus, most of the cold-upregulated genes are late-response genes (Figure 1). Indeed, Venn diagram analysis shows that 435 (66.4%) genes were induced exclusively at 24 h of cold treatment (Figure 1), while only 20 (3.1%) and 17 (2.6%) genes were upregulated exclusively at 3 or 6 h of cold treatment, respectively. Out of the cold upregulated genes, 66 genes (10.1%) had a high level of cold induction at all time points.

Most of the 284 downregulated genes were downregulated also only after 24 h of cold treatment. Only four genes (At1g05610, glucose-1-phosphate adenylyltransferase; At2g23900, polygalacturonase; At5g34880, hypothetical protein; At5g38035, copia-like retrotransposon) showed a substantial downregulation at 3 h, and the downregulation of one of the four (At5g38035, copia-like retrotransposon) was also observed at 6 and 24 h (Figure 1). The contrasting results among the numbers of cold downregulated genes at each time point suggest that although cold downregulated genes may play a role in cold responses in Arabidopsis, the downregulation is not a major part of the early response to cold stress. The upregulation of early genes by low temperature may be important for both upregulation and downregulation of late-response genes.

Functional Categorization of Cold-Regulated Genes

To distinguish the kinetics of regulation under cold stress, we designated genes with transcript level changes only at 3 or 6 h or at both 3 and 6 h as early and transiently upregulated or downregulated, respectively. Genes that changed exclusively at 24 h were considered late upregulated/downregulated genes. Genes with expression changes at 3 and 24 h, 6 and 24 h, or 3, 6, and 24 h were grouped as early and continually upregulated or downregulated, respectively.

Our cold-regulated genes were categorized into 19 functional groups using the Functional Catalogue at http://mips.gsf.de/projects/funcat, with manual adjustment when necessary (Table 1; Ruepp et al., 2004). Interestingly, different functional categories appeared to be activated at different time points after cold treatment. Although genes without significant similarity to known genes or functions were in fact the largest group of cold-regulated genes, our analysis here focused on genes with sequence homology to known genes. Among the early transiently upregulated genes, the largest group were genes involved in transcription and the next largest were signal transduction genes; 19 genes are involved in transcription, and 12 are in signal transduction (Table 1). On the other hand, out of the early continually upregulated genes, 26 and 22 are involved in transcription and cell defense, respectively (Table 1). Genes involved in transcription (68 genes) and metabolism (67 genes) were the major groups among late upregulated genes. The large number of genes involved in metabolism suggests that plants start to undergo substantial changes in metabolism later in the cold, after an initial inhibition of metabolism due to reduced enzymatic activities under cold. Previous physiological and metabolomic studies have shown many metabolic changes during cold acclimation, such as increased accumulation of soluble sugars and other compatible osmolytes (Wanner and Junttila, 1999; Cook et al., 2004). In summary, genes involved in transcription (113 genes) and metabolism (92 genes) are the two major groups of cold upregulated genes, which are followed by genes involved in defense (67 genes) and signal transduction (63 genes).

Table 1.

Functional Categorization of Cold-Regulated Genes

| Cold Upregulated

|

Cold Downregulated

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETU

|

ECU

|

LU

|

Subtotal

|

ETD

|

ECD

|

LD

|

Subtotal

|

Total

|

||||||||||

| Functional Category | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Metabolism | 6 | 7.5 | 19 | 12.0 | 67 | 13.7 | 92 | 12.6 | 2 | 10.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 67 | 24.1 | 70 | 23.1 | 162 | 15.7 |

| Energy | 1 | 1.3 | 5 | 3.2 | 18 | 3.7 | 24 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.0 | 30 | 2.9 | ||

| Storage protein | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Cell cycle and DNA processing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9 | 1.8 | 9 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 6 | 2.2 | 7 | 2.3 | 16 | 1.6 | |||

| Transcription | 19 | 23.8 | 26 | 16.5 | 68 | 13.9 | 113 | 15.5 | 1 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 19 | 6.8 | 20 | 6.6 | 133 | 12.9 | |

| Protein synthesis | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.5 | 2 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 4 | 1.3 | 8 | 0.8 | |||

| Protein fate (folding, modification, and destination) | 1 | 1.3 | 8 | 5.1 | 22 | 4.5 | 31 | 4.3 | 3 | 15.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 13 | 4.7 | 17 | 5.6 | 48 | 4.7 |

| Protein with binding function or cofactor requirement | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.8 | 5 | 1.7 | 10 | 1.0 | |||

| Cellular transport, transport facilitation, and transport routes | 4 | 5.0 | 8 | 5.1 | 26 | 5.3 | 38 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13 | 4.7 | 13 | 4.3 | 51 | 4.9 | ||

| Cellular communication/signal transduction mechanism | 12 | 15.0 | 11 | 7.0 | 40 | 8.2 | 63 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 18 | 6.5 | 19 | 6.3 | 82 | 8.0 | |

| Cell rescue, defense, and virulence | 6 | 7.5 | 22 | 13.9 | 39 | 8.0 | 67 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13 | 4.7 | 13 | 4.3 | 80 | 7.8 | ||

| Interaction with the cellular environment | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.1 | |||||

| Interaction with the environment (systemic) | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.8 | 5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5 | 1.8 | 5 | 1.7 | 10 | 1.0 | |||

| Transposable elements and viral and plasmid proteins | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 20.0 | 1 | 0.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 5 | 0.5 | |

| Cell fate | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.4 | 7 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.7 | |||||

| Development (systemic) | 0.0 | 1 | 0.6 | 3 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.7 | 6 | 0.6 | |||

| Biogenesis of cellular components | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.9 | 7 | 1.4 | 12 | 1.6 | 1 | 5.0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.2 | 7 | 2.3 | 19 | 1.8 | |

| Subcellular localization | 4 | 5.0 | 6 | 3.8 | 14 | 2.9 | 24 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 6 | 2.2 | 6 | 2.0 | 30 | 2.9 | ||

| No clear classification/unclassified | 25 | 31.3 | 45 | 28.5 | 156 | 31.8 | 226 | 31.0 | 10 | 50.0 | 0.0 | 96 | 34.5 | 106 | 35.0 | 332 | 32.2 | |

| Total | 80 | 100.0 | 158 | 100.0 | 490 | 100.0 | 728 | 100.0 | 20 | 100.0 | 5 | 100.0 | 278 | 100.0 | 303 | 100.0 | 1031 | 100.0 |

Note that among 939 cold-responsive genes, 132 belong to multiple functional categories and 10 are missing in the Functional Catalogue. The missing 10 genes were manually grouped into different functional categories following database searches. ETU/D, early transiently upregulated/downregulated; ECU/D, early continually upregulated/downregulated; LU/D, late upregulated/downregulated.

Cold downregulated genes showed slower kinetics. Only 20 genes were downregulated early and transiently, and five genes were downregulated early and continually under cold stress, while most of the genes (278 genes) were downregulated late by low temperature (Table 1). As the majority of cold downregulated genes were down after 24 h of cold treatment, late downregulated genes represent the major groups of cold downregulated genes. Among the late downregulated genes, genes involved in metabolism are the largest group (67), with fewer genes in other categories. Thus, low temperature stress mainly downregulates metabolism genes, and the downregulation happens late in the cold.

Cold Regulation of Signal Transduction Components

Consistent with a role of Ca2+ in early cold signal transduction, Ca2+ binding proteins were the main signaling components induced at the early time points during cold stress (Table 2; see Supplemental Tables 3, 4, and 10 online). In fact, two of the four early transiently upregulated protein kinases require indirect or direct Ca2+ involvement for kinase activity (At1g01140, SOS2-like protein kinase 6/CBL-interacting protein kinase 9; At5g66210, calcium-dependent protein kinase), making eight genes Ca2+ related out of 12 early transiently upregulated genes. Protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation have been implicated in cold signal transduction. Indeed, the number of protein kinases and phosphatases with altered expression was the largest (total of 32 genes among 82 cold-regulated signaling genes) (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). The induction of protein kinases was observed to exhibit all types of kinetics, whereas protein phosphatase gene induction occurred preferably at the late time point (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). In addition, the only signaling component that was early and continually downregulated was a protein phosphatase 2C (At5g02760).

Table 2.

Cold-Regulated Signaling Genes

| Cold Upregulated

|

Cold Downregulated

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETU

|

ECU

|

LU

|

Subtotal

|

ETD

|

ECD

|

LD

|

Subtotal

|

Total

|

||||||||||

| Category | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Calcium binding protein | 6 | 50.0 | 3 | 27.3 | 5 | 12.5 | 14 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 5.3 | 15 | 18.3 | ||

| Protein phosphatase | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 9.1 | 8 | 20.0 | 10 | 15.9 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 1 | 5.6 | 2 | 10.5 | 12 | 14.6 | |

| Protein kinase | 4 | 33.3 | 4 | 36.4 | 8 | 20.0 | 16 | 25.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 22.2 | 4 | 21.1 | 20 | 24.4 | ||

| Receptor-like kinase | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 | 17.5 | 7 | 11.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 | 38.9 | 7 | 36.8 | 14 | 17.1 | ||||

| Blue light teceptor | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 | 1 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | ||||||

| Histidine kinase | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 1.2 | |||||

| Respone regulator | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 2.5 | 2 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 16.7 | 3 | 15.8 | 5 | 6.1 | |||

| Lipid signaling protein | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 9.1 | 6 | 15.0 | 8 | 12.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 5.3 | 9 | 11.0 | ||

| GTP-related protein | 0.0 | 1 | 9.1 | 4 | 10.0 | 5 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 6.1 | ||||

| Total | 12 | 100.0 | 11 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 | 63 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 18 | 100.0 | 19 | 100.0 | 82 | 100.0 |

Note that three pseudoresponse regulators (APRR1, At5g61380; APRR2, At4g18020; APRR5, At5g24470) are included in the response regulator category.

Fourteen genes for receptor-like kinases (RLKs) were cold regulated (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). Notably, all these cold-regulated RLKs responded late in the cold, which suggests that they might perceive secondary signals generated by early cold responses. Among the cold-regulated RLKs, two RLKs have been studied in detail. The leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase, RKL1 (At1g48480), was predominantly expressed in stomatal cells and was induced by wounding, pathogen, and salicylic acid (Tarutani et al., 2004a, 2004b). The RECEPTOR-LIKE PROTEIN KINASE 1 (RPK1) gene (At1g69270) has been reported to be induced by abscisic acid (ABA), dehydration, high salt, and cold (Hong et al., 1997). Recent work indicates that RPK1 plays an important role in ABA signal transduction (Osakabe et al., 2005). These results suggest that cold signal transduction shares at least in part some common pathways with other biotic, abiotic, and ABA signaling through these RLKs.

Intriguingly, the expression of a type-A response regulator, ARR16 (At2g40670), and a type-B response regulator, ARR10 (At4g31920), was reduced at the late time point during cold stress (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). These response regulators of the two-component system have been implicated in cytokinin signaling (Hwang and Sheen, 2001; Kiba et al., 2002). Thus, this observation indicates an interaction between cytokinin signaling and cold response. Consistent with this notion, histidine kinase2 (At5g35750), another component of two-component systems, is also cold regulated (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online).

The pseudoresponse regulator APRR1 (At5g61380) was cold upregulated late, while another, APRR5 (At5g24470), was upregulated early and continually. A third pseudoresponse regulator, APRR2 (At4g18020), was cold downregulated late (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). Pseudoresponse regulators are proteins that lack the conserved Asp residue that in typical response regulators is the phosphorylation target of the upstream kinase in two-component systems (Hwang et al., 2002). APRR1 is also called TIMING OF CAB EXPRESSION1 and is an essential component of the central oscillator for circadian rhythms in Arabidopsis (Strayer et al., 2000; Mizuno, 2004). APRR5 has also been implicated in circadian rhythms (Yamamoto et al., 2003; Fujimori et al., 2005). It is worth noting that our cold treatment started at noon, that is, 6 h after dawn, and the seedlings were grown in a 16-h-light and 8-h-dark cycle for 2 weeks before the treatments. A previous report showed that the peaks of mRNA accumulation of APRR1 and APRR5 occurred at 12 and 8 h after dawn with 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod conditions (Matsushika et al., 2000). Therefore, our control (i.e., 0 h treatment at noon) expression level should already have been at least half or close to the maximum expression level. Significant cold induction of APRR1 and APRR5 genes took place mainly at 24 h (i.e., at noon after one full circadian cycle) under cold treatment. Thus, the higher expression levels of APRR1 and APRR5 genes at 0°C appear to be the consequence of cold regulation rather than circadian effects.

Nine genes involved in phospholipid signaling were cold regulated, and almost all (eight genes) were upregulated by cold stress (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). These include four phospholipase Cs (ATPLC1, At5g58670; ATPLC4, At5g58700; ATPLC5, At5g58690; a putative phospholipase C [PLC], At4g34920), one phospholipase D (PLDα1, At3g15730), two diacylglycerol kinases (ATDGK1, At5g07920; ATDGK2, At5g63770), one inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase II (IP5PII; At4g18010), and one 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase/inositol polyphosphate 1-phosphatase (IPPase; At5g63990) (see Supplemental Table 10 online). All of these genes were cold regulated at the late time point except for IP5PII (At4g18010) and ATDGK1 (At5g07920), which are early and transiently and early and continuously induced under cold stress, respectively (see Supplemental Table 10 online). Because all of these genes function in phospholipid-based signaling, their induction/repression by cold stress strongly suggests that phospholipid second messengers are an important part of cold signaling. PLCs act on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, generating inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG). IP3 is known to trigger the release of Ca2+ from internal stores, and DAG has been shown to activate protein kinase C in animal cells (Irvine, 1992). There are no homologs of protein kinase C in Arabidopsis, and DAG is converted to phosphatidic acid (PA) by diacylglycerol kinases (Munnik, 2001). PA can also be generated by direct hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids, such as phosphatidylcholine and phophatidylethanolamine by phospholipase D (PLD). There are accumulating lines of evidence that PA is involved in cold signaling. During cold stress, PA content increased in Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures, and this increase was due to the activation of PLC and PLD (Ruelland et al., 2002). Studies with Arabidopsis mutant or overexpression lines of PLDs supported their involvement in plant cold tolerance (Welti et al., 2002; Li et al., 2004). Consistent with these reports, cold induction of genes involved in PA production, such as diacylglycerol kinases and a PLD, suggests that PA is an important part of plant cold responses as reported for wounding and osmotic stress (Frank et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Katagiri et al., 2001).

The FRY1 bifunctional 3′(2′),5′-bisphosphate nucleotidase/inositol polyphosphate 1-phophatase was shown to play an important role as an IPPase (Xiong et al., 2001). Loss-of-function mutations in FRY1 resulted in a significant increase in the expression of cold-responsive genes, which supports a role of IPPase in attenuating the IP3 signal triggered by cold (Xiong et al., 2001). The expression of one of its paralogs (Atg563990) located next to FRY1 on chromosome 5 was significantly increased during cold (see Supplemental Table 10 online), suggesting its role in cold stress as an IPPase. Because most of these IP3-related genes were induced late, IP3 signaling is likely to be a late event during cold stress. Nevertheless, the early and transient induction of IP5PII (At4g18010) suggests that an early involvement of IP3 in cold signaling cannot be ruled out completely.

Cold stress also induced two Rab GTPase genes (ATRABC1/ATRAB18, At1g43890; ATRABG3d, At1g52280) (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). Although no in planta function of these genes has been established in Arabidopsis, Rab GTPases are known to function in intracellular membrane trafficking (Zerial and McBride, 2001). Thus, cold upregulation of the two Rab GTPase indicates that active membrane trafficking might take place under cold stress.

A putative GDP/GTP pyrophosphokinase (RELA/SPOT HOMOLOG 2 [RSH2], At3g14050) was early and continually upregulated by cold (Table 2; see Supplemental Table 10 online). This gene encodes a plant homolog of RelA and SpoT (van der Biezen et al., 2000). In bacteria, RelA (p)ppGpp synthase and SpoT (p)ppGpp hydrolase determine the level of guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp) and guanosine pentaphosphate (pppGpp) in response to starvation and other stress conditions. Accumulation of (p)ppGpp in response to unfavorable conditions initiates the stringent response. Among three Arabidopsis RelA and SpoT homologs, RSH1 interacts with a pathogen resistance protein (RPP5) in the yeast two-hybrid system and confers phenotypes associated with (p)ppGpp synthesis in Escherichia coli and Streptomyces coelicolor (van der Biezen et al., 2000). Recently, it was reported that RSH from the halophyte Suaeda japonica, a RelA and SpoT homolog more closely related to RSH2 and RSH3 than RSH1, confers salt tolerance when expressed in E. coli and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Yamada et al., 2003). Thus, despite the lack of functional analysis in plants, the induction of RSH2 under cold stress suggests a possible occurrence of (p)ppGpp-mediated signal transduction under cold stress.

Cold Regulation of Transcription Factors

Studies of the cold-induced DREB1/CBF family of transcription factors have demonstrated the importance of transcription factors in plant freezing tolerance (Jaglo-Ottosen et al., 1998; Kasuga et al., 1999). To understand the regulation of transcription factors by cold, we surveyed their expression levels during cold stress (Tables 3 and 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online). Among the 655 cold upregulated genes, 113 (17.3%) genes are annotated to function in transcription. By contrast, only 20 transcription-related genes (7.0%) were found among the 284 downregulated genes (Table 3). Transcription category genes include both transcription factors that have DNA binding domain(s) and transcription activation/repression domain(s) and other factors that modulate the activity of transcription factors. There are 95 transcription factors and 18 other transcriptional regulators among cold upregulated transcription category genes (Tables 3 and 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online). Eighteen transcription factors and two other transcriptional regulators belong to the cold downregulated transcription category (Tables 3 and 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online).

Table 3.

Cold-Regulated Genes Involved in Transcription: Transcription Factors with Known DNA Binding Domains

| Cold Upregulated

|

Cold Downregulated

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETU

|

ECU

|

LU

|

Subtotal

|

ETD

|

ECD

|

LD

|

Subtotal

|

Total

|

||||||||||

| Category | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| AP2/ERF | 7 | 36.8 | 11 | 42.3 | 3 | 4.4 | 21 | 18.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 22 | 16.5 | ||

| B3 (ARF) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | |||||

| bZIP | 0.0 | 1 | 3.8 | 5 | 7.4 | 6 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 4.5 | ||||

| CCAAT | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | |||||

| CG-1 (CAMTA4) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 | |||||

| GRAS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.9 | 2 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 3 | 2.3 | ||||

| Homeodomain | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 1.5 | ||||

| HSF | 1 | 5.3 | 2 | 7.7 | 1 | 1.5 | 4 | 3.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 3.0 | |||

| MADS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 1 | 0.8 | |||||

| MYB | 1 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 10 | 14.7 | 11 | 9.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 12 | 9.0 | |||

| bHLH | 1 | 5.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 | 36.8 | 7 | 35.0 | 8 | 6.0 | ||||

| NAC | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 7 | 10.3 | 9 | 8.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 10 | 7.5 | ||

| SPB | 0.0 | 1 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 1 | 5.0 | 2 | 1.5 | ||||

| Trihelix | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 10.5 | 2 | 10.0 | 3 | 2.3 | ||||

| WRKY | 5 | 26.3 | 1 | 3.8 | 2 | 2.9 | 8 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 6.0 | |||

| Zn | 2 | 10.5 | 7 | 26.9 | 18 | 26.5 | 27 | 23.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2 | 10.5 | 2 | 10.0 | 29 | 21.8 | ||

| ETC | 1 | 5.3 | 2 | 7.7 | 15 | 22.1 | 18 | 15.9 | 1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 5.3 | 2 | 10.0 | 20 | 15.0 | |

| Total | 19 | 100.0 | 26 | 100.0 | 68 | 100.0 | 113 | 100.0 | 1 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 100.0 | 20 | 100.0 | 133 | 100.0 |

Note that ETC includes the transcription regulatory proteins, one transcription factor with unclassified DNA binding domain (At3g61260), and general transcription factor TFIIB (At2g41630). AP2, APETALA2; ERF, ethylene-responsive element binding factor; ARF, auxin response factor; HSF, heat shock transcription factor; CAMTA, calmodulin binding transcription activators; CCAAT, CCAAT binding motif; SPB, squamosa promoter binding.

Table 4.

Cold-Regulated Genes Involved in Transcription: Transcription Regulators Indirectly Involved in Transcription Processes

| Category | AGI IDa | Gene Name | Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromatin | At1g63020 | RNA polymerase IV (RNA polymerase D) subunit; NRPD1a | ECU |

| At5g63330 | DNA binding bromodomain-containing protein | ECU | |

| At5g50320 | GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT) family | LU | |

| At3g12980 | Histone acetyltransferase 5 (HAC5) | LU | |

| At5g26040 | Histone deacetylase, putative | LU | |

| At5g14270 | Bromodomain-containing protein | LU | |

| At5g10550 | Bromodomain protein like | ETD | |

| Splicing | At1g28060 | snRNP; similarity to U4/U6 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein hPrp3 | LU |

| At4g03430 | Putative pre-mRNA splicing factor | LU | |

| At4g05410 | U3 snoRNP-associated–like protein | LU | |

| At4g25500 | STA1; Arg/Ser-rich splicing factor RSp40 | LU | |

| At5g46920 | Intron maturase, type II family protein | LU | |

| Turnover | At3g44260 | CCR4-associated factor 1-like protein | ETU |

| At2g22090 | UBP1 interacting protein, putative | LD | |

| Other | At1g69250 | Nuclear transport factor 2 (NTF2) family | LU |

| At5g59950 | RNA and export factor binding protein, putative | LU | |

| At2g42520 | DEAD box RNA helicase, putative | LU | |

| At4g34910 | DEAD/DEAH box helicase (RH16) | LU |

AGI, Arabidopsis Genome Initiative.

When classified by their characteristic DNA binding domains, except for one that encodes a DNA binding protein with a nonclassified binding domain (At3g61260), the 95 cold upregulated transcription factors fall into 15 families (Table 3). Transcription factors with APETALA 2/ETHYLENE-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTOR (AP2/ERF) and Zn finger domains are the two major families, accounting for 21 genes and 27 genes of the 95 upregulated transcription factors, respectively. Interestingly, these two groups of transcription factors appear to act in different time frames. The AP2/ERF family was mainly induced early transiently and continually during cold, whereas the Zn finger family was mostly late induced under cold stress. Therefore, the AP2/ERF transcription factors may play a major role early in the cold response, as is also supported by the fact that DREBs/CBFs are in the AP2/ERF family and are important for the activation of many late cold-responsive genes (Fowler and Thomashow, 2002).

Our microarray data revealed that cold induction of basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors occurred mainly at a late time point (Table 3; see Supplemental Table 11 online). bZIP transcription factors play a role in plant pathogen responses, light signaling, and ABA and abiotic stress signaling (Jakoby et al., 2002). We found that two ABA-responsive element binding factors (ABF1, At1g49720; ABF4/AREB2, At3g19290) and ABA INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5, At2g36270) genes were cold induced. These ABFs/ABREBs are highly similar to ABI5 and belong to group A bZIP transcription factors (Jakoby et al., 2002). Although they are all ABA responsive, the expression patterns of ABFs/ABREBs in response to various stress treatments are different (Choi et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2000). In addition, Arabidopsis plants overexpressing ABF2/AREB1, ABF3, or ABF4/AREB2 display distinct stress responses (Kang et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2004), suggesting specific or partially overlapping functions of ABFs/ABREBs in stress responses.

Several transcription factors involved in plant development (e.g., ARF, GRAS, Homeodomain, MADS, and NAC) were regulated by cold stress (Table 3; see Supplemental Table 11 online). For example, auxin response factor 7/NONPHOTOTROPHIC HYPOCOTYL 4 (ARF7/NPH4, At5g20730) was cold upregulated at the late time point. ARF7/NPH4 functions in auxin-dependent differential cell expansion of hypocotyls (Stowe-Evans et al., 1998; Harper et al., 2000; Tatematsu et al., 2004; Okushima et al., 2005). Other examples include NAC transcription factors that are mainly cold induced at the late time point. Plant-specific NAC family transcription factors have a conserved NAC domain at the N termini of the proteins (Olsen et al., 2005) and have been implicated in plant development (Souer et al., 1996; Aida et al., 1997; Sablowski and Meyerowitz, 1998; Xie et al., 2000; Takada et al., 2001; Vroemen et al., 2003). It was recently reported that several NAC transcription factors are also involved in biotic and abiotic stress responses (Collinge and Boller, 2001; Hegedus et al., 2003; Fujita et al., 2004; Tran et al., 2004). Thus, these transcription factors might be effectors of cold signaling and function in reprogramming plant development to cope with cold stress.

Interestingly, four heat shock transcription factors (HSFs) and eight WRKY transcription factors were also cold responsive and were all upregulated (Table 3; see Supplemental Table 11 online). HSF and WRKY plant transcription factors have been implicated in heat stress and pathogen responses, respectively (Eulgem et al., 2000; Nover et al., 2001). These results suggest that several HSF and WRKY factors can be involved in plant responses to multiple stresses. Recently, it was shown that WRKY factors are important in senescence, morphogenesis, and ABA and gibberellin signaling in aleurone cells (Robatzek and Somssich, 2001; Johnson et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2004; Xie et al., 2005). Also, WRKY expression was induced by various abiotic stresses (Pnueli et al., 2002; Rizhsky et al., 2002; Seki et al., 2002).

Most of the MYB transcription factors (10 out of 12 genes) were cold induced late, while most of the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors (seven out of eight genes) were cold downregulated late (Table 3; see Supplemental Table 11 online). As MYB and bHLH proteins often interact with each other to control transcription (Stracke et al., 2001; Heim et al., 2003; Ramsay and Glover, 2005), this differential expression of MYB and bHLH transcription factors suggests that the regulation of some cold-responsive genes may be achieved by modulating the ratio of these partner factors.

Cold Regulation of Other Transcription Regulators

Our microarray data revealed that the expression levels of two mitochondrial genes (cox1 and nad6) increased during cold stress (see Supplemental Table 2 online). cox1 (AtMg01360) encodes cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 and nad6 (AtMg00270) encodes NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6. Related to this, we noticed that seven genes encoding a protein with a pentatricopeptide repeat (At1g74750, At3g57430, At3g60980, At4g36680, At5g02860, At5g25630, and At5g61370) are cold regulated (see Supplemental Tables 1, 5, and 9 online). All but At5g25630, which shows late downregulated kinetics, were late induced by cold. Proteins with a pentatricopeptide repeat are known to be involved in organellar RNA metabolism (Lurin et al., 2004). We reported previously that a mutation in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial complex I subunit resulted in impaired cold acclimation and reduced cold-responsive gene expression (B.-h. Lee et al., 2002), suggesting the importance of coordination of nuclear cold-responsive gene expression and mitochondrial functions. Our microarray data further support the notion that proper organellar functions, especially mitochondrial electron transport, are important for plant cold responses, including cold-regulated gene expression.

Expression of many genes involved in RNA metabolism and chromatin remodeling was altered by cold stress (Table 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online). Expression of four pre-mRNA splicing factors (At1g28060, At4g03430, At4g05410, and At4g25500), two DEAD box RNA helicases (At2g42520 and At4g34910), and two RNA transport factors (At1g69250 and At5g59950) are increased by cold stress. These genes are known to be involved in RNA metabolism, including splicing, ribosome biogenesis, mRNA export, translational regulation, and RNA degradation (Farina and Singer, 2002; Jurica and Moore, 2003; Rocak and Linder, 2004). In addition, CCR4-associated factor 1 (CAF1)-like protein (At3g44260) is early and transiently cold induced. CAF1 is a critical component of the major cytoplasmic deadenylase in yeast, which initiates mRNA turnover by shortening of the poly(A) tail (Tucker et al., 2001). Also, UBP1-interacting proteins are thought to be involved in a complex that recognizes U-rich sequences in plant 3′ untranslated regions for the stabilization of mRNAs in the nucleus (Lambermon et al., 2002). Thus, induction of the CAF1-like protein and repression of the UPB1-interacting protein under cold stress might enhance the turnover of specific mRNA transcripts.

We have shown that mutations in an Arabidopsis DEAD box RNA helicase (LOS4, AT3G53110) affect mRNA export, cold sensitivity, and cold-responsive gene expression (Gong et al., 2002, 2005). Moreover, an Arabidopsis sta1 mutant defective in one of our cold upregulated pre-mRNA splicing factors (At4g03430) displayed hypersensitivity to cold stress and mis-splicing of at least one cold-responsive gene, while it enhanced the transcript stability of some genes (B.-h. Lee and J.-K. Zhu, unpublished data). Taken together, the cold induction of several genes for RNA metabolism supports a strong connection between RNA metabolism and cold responses.

Interestingly, many genes that alter the chromatin status showed cold-regulated expression (Table 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online). One histone deacetylase (At5g26040), two histone acetylases (At3g12980 and At5g50320), and three bromodomain-containing proteins (At5g10550, At5g14270, and At5g63330) were among the cold-regulated genes involved in chromatin remodeling. Histone acetylases add acetyl groups to histone tails, whereas histone deacetylases remove acetyl groups from the histone tail. The bromodomain recognizes the acetylated Lys residues in histone tails (Eberharter and Becker, 2002). The kinetics of cold regulation of these genes differs, suggesting a complex and dynamic nature of cold-responsive gene regulation at the chromatin level.

We found that NRPD1a (At1g63020) was early and continually cold upregulated (Table 4; see Supplemental Table 11 online). NRPD1a encodes a plant-specific RNA polymerase IV subunit and is important in small interfering RNA-directed de novo DNA methylation important for silencing of transposon and other repetitive DNA in plants (Herr et al., 2005; Onodera et al., 2005). Recently, many small RNAs that are potentially associated with gene silencing were isolated from a small RNA library constructed from abiotic stress–treated Arabidopsis (Sunkar and Zhu, 2004). Taken together, our finding suggests that some endogenous small RNAs might be increased by cold treatment, and NRPD1a may play an important role in this process.

In conclusion, cold-regulated gene expression is not only controlled by promoter binding transcription factors but may also be regulated at the posttranscriptional and chromatin levels.

Cold Regulation of Genes Related to Plant Hormone Biosynthesis and Signaling

Plant hormones are crucial regulators of growth and development. Plants grown under cold stress display growth and development patterns different from those under normal growth conditions, which might have to do with an altered hormone homeostasis and/or signal transduction in cold-stressed plants. To investigate this possibility, we inspected the expression pattern of hormone-related genes under cold treatment.

ABA is an important stress hormone that mediates abiotic stress signal transduction and tolerance. ABA accumulates in response to abiotic stress, such as drought and salt (Xiong and Zhu, 2003). Cold stress also increases endogenous ABA levels in plants but to a much lesser extent (Lang et al., 1994). Because ABA biosynthesis is mainly regulated at the transcriptional level (Xiong and Zhu, 2003), it is of interest to see whether ABA biosynthesis genes are regulated by cold. According to our microarray data, none of the known ABA synthesis genes were cold regulated, suggesting that ABA biosynthesis is not a major event in cold stress, consistent with previous studies (Lang et al., 1994).

Although ABA levels may not change greatly under cold stress, ABA signal transduction could be involved in cold responses. Cold stress induces many genes that are also induced by ABA and osmotic stress (Thomashow, 1999). Furthermore, many ABA-induced genes were induced by cold according to our microarray data (Table 5). As described above, a bZIP transcription factor, ABF1 (At1g49720), which can bind to the ABA-responsive element in ABA-responsive promoters (Choi et al., 2000), is early and continually induced by cold (Table 5). A related gene, ABF4/AREB2 (At3g19290), was also induced by cold. Thus, it is possible that the cold induction of some ABA-inducible genes might be mediated by ABF1 and ABF4.

Table 5.

Cold Upregulated Genes with Hormone-Related Roles

| Hormone | AGI ID | Gene Name | Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABA | At4g17615 | Calcineurin B-like protein 1 (CBL1) | ETU |

| At5g52310 | Low-temperature-induced protein 78 | ECU | |

| At1g20440 | Dehydrin (COR47) | ECU | |

| At1g20450 | Dehydrin (ERD10) | ECU | |

| At4g24960 | ABA-induced–like protein | ECU | |

| At5g15960 | Stress-induced protein KIN1 | ECU | |

| At1g49720 | ABA-responsive elements binding factor (ABF1) | ECU | |

| At2g36270 | ABA-responsive element binding protein (ABI5) | LU | |

| At5g58670 | Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C | LU | |

| At4g15910 | Drought-induced protein (Di21) | LU | |

| At1g29395 | Similar to the cold acclimation protein WCOR413 in wheat | LU | |

| At1g28200 | GRAM domain-containing protein | LU | |

| At3g19290 | ABA-responsive elements binding factor (ABF4/ABREB2) | LU | |

| At3g11410 | Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), putative | LU | |

| At4g26080 | Protein phosphatase ABI1 | LU | |

| At5g50720 | ABA-responsive protein (HVA22e) | LU | |

| At2g19450 | Acyl CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (DGAT) | LU | |

| At1g69270 | Receptor protein kinase-related (RPK1) | LU | |

| At5g13200 | GRAM domain-containing protein | LU | |

| Auxin | At5g54490 | PINOID binding protein containing putative calcium binding motifs | ETU |

| At1g13260 | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative (RAV1) | ETU | |

| At5g35735 | Auxin-induced protein family | LU | |

| At5g20730 | Auxin response factor (ARF7) | LU | |

| At5g53590 | Auxin-induced (indole-3-acetic acid–induced) protein family | LU | |

| Ethylene | At1g28370 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 11, putative | ETU |

| At4g17490 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor (ERF6) | ETU | |

| At5g51190 | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative | ETU | |

| At4g11280 | 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase 6 (ACS6) | ECU | |

| At3g15210 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 4 (ERF4) | ECU | |

| At5g47230 | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 5 (AtERF5) | ECU | |

| At1g67310 | Calmodulin binding protein | LU | |

| At3g21420 | Oxidoreductase, 2OG-Fe(II) oxygenase family | LU | |

| At4g20880 | Ethylene-regulated transcript 2 (ERT2) | LU | |

| GA | At1g02400 | GA 2-oxidase, putative | LU |

| At5g17490 | GA response modulator, putative (RGL3) | LU |

Gibberellins (GAs) are involved in many plant developmental processes, including seed development, stem elongation, flowering, and fruit development (Richards et al., 2001). Many genes involved in GA biosynthesis have been isolated and characterized (Hedden and Kamiya, 1997). In several plants, such as rice (Oryza sativa), pea (Pisum sativum), and Arabidopsis, the transcript level of GA 20-oxidase, which catalyzes the conversion of C20-GA into C19-GA, is downregulated by GA. By contrast, treatment with GA biosynthesis inhibitor resulted in an increased level of GA 20-oxidase transcripts. In addition to this GA-induced negative feedback regulation of GA biosynthesis, positive regulation of a GA catabolic enzyme, GA 2-oxidase, was also reported (Thomas et al., 1999). Therefore, changes in the expression of these genes can indicate GA homeostasis under cold stress.

In this study, we found that two GA 20-oxidases (At3g60290 and At4g03060) were downregulated, and one, GA 2-oxidase (At1g02400), was cold induced (Tables 5 and 6). These expression changes suggest the possibility of increased GA accumulation under cold stress. Although this potential GA accumulation under low temperature conditions might be part of the vernalization process that promotes flowering, it is also possible that GA might affect cold stress signaling and tolerance. Recently, it was demonstrated that in imbibed seeds, cold treatment enhances the biosynthesis of GA via the activation of GA3Ox1 (or GA 3β hydroxylase, GA4, At1g15550) to promote seed germination (Yamauchi et al., 2004).

Table 6.

Cold Downregulated Genes with Hormone-Related Roles

| Hormone | AGI ID | Gene Name | Kinetics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auxin | At2g45210 | Putative auxin-regulated protein; SAUR gene family | ETD |

| At4g38840 | Auxin-induced protein-like; SAUR gene family | ETD | |

| At4g39950 | CYP79B2 | LD | |

| At4g31500 | CYP83B1 | LD | |

| At5g54510 | Auxin-responsive–related protein | LD | |

| At3g25290 | Auxin-induced protein family | LD | |

| At2g01420 | Auxin transporter splice variant B (PIN4) | LD | |

| At1g29430 | Auxin-induced protein, putative; SAUR gene family | LD | |

| At1g29500 | Auxin-induced protein, putative; SAUR gene family | LD | |

| At4g15550 | UDP-glucose:indole-3-acetate β-d-glucosyltransferase (iaglu) | LD | |

| At1g24100 | Putative indole-3-acetate β-glucosyltransferase | LD | |

| At4g34770 | Auxin-induced protein family; SAUR gene family | LD | |

| At1g72430 | Auxin-induced protein-related; SAUR gene family | LD | |

| At1g28130 | Auxin-regulated GH3 protein-related | LD | |

| At2g47750 | Auxin-responsive protein-related | LD | |

| At2g36910 | Multidrug resistance P-glycoprotein (pgp1) | LD | |

| Brassinosteroid | At3g61460 | BRH1 RING finger protein | ETD |

| At5g05690 | CPD, DWF3 | LD | |

| At3g50750 | Expressed protein | LD | |

| Cytokinin | At5g35750 | Histidine kinase-related protein; AHK2 | LD |

| At3g63440 | Cytokinin oxidase family protein | LD | |

| At4g31920 | ARR10; type B two-component response regulator protein | LD | |

| At2g40670 | ARR16; type A two-component response regulator protein | LD | |

| Ethylene | At5g25190 | Ethylene-responsive element binding protein, putative | LD |

| GA | At3g60290 | SRG1-like protein; GA 20-oxidase | LD |

| At1g14920 | GA response modulator (GAI/RGA2) | LD | |

| At4g03060 | Putative oxidoreductase; GA 20-oxidase | LD | |

| Jasmonate | At1g17990 | 12-Oxophytodienoate reductase, putative | LD |

| Salicylic acid | At1g21270 | Wall-associated kinase 2 (WAK2) | LD |

GA signaling is mediated through DELLA proteins that act as negative regulators (Olszewski et al., 2002). Upon GA perception, some DELLA protein is removed from the nucleus by degradation, releasing the repression of GA signaling. For example, in rice, the level of nuclear-localized SLR1-green fluorescent protein fusion decreased with GA treatment (Itoh et al., 2002). The Arabidopsis DELLA protein REPRESSOR OF GA (RGA) was shown to be regulated in a similar way (Silverstone et al., 2001). Rice has only one DELLA protein (Ikeda et al., 2001), but Arabidopsis has five: GA INSENSITIVE (GAI, At1g14920), RGA (At2g01570), RGA-LIKE PROTEIN 1 (RGL1, At1g66350), RGL2 (At3g03450), and RGL3 (At5g17490). Not all of these proteins are regulated by degradation. GA treatment did not lead to GAI and RGL1 degradation (Fleck and Harberd, 2002; Wen and Chang, 2002). RGL2 appears to be transcriptionally regulated by GA during seed germination (S. Lee et al., 2002). We found that GAI (At1g14920) was downregulated and RGL3 (At5g17490) upregulated under cold, possibly by cold-induced GA (Tables 5 and 6). Thus, GAI and RGL3 might be regulated at the mRNA level. Since the physiological function of RGL3 is unknown, our observation that it is upregulated by cold provides a clue to its function.

CONSTITUTIVE PHOTOMORPHOGENIC DWARF/DWARF3 (CPD/DWF3, At5g05690) was cold downregulated 24 h after cold treatment (Table 6). CPD/DWF3 encodes a member of the cytochrome P450 90A family required for C23 hydroxylation of cathasterone to teasterone in brassinolide biosynthesis (Szekeres et al., 1996). CPD/DWF3 expression is specifically downregulated by brassinolide treatment but not by other plant hormones (Mathur et al., 1998). Our observation of CPD/DWF3 downregulation by cold suggests that brassinosteroid level might be lowered in the cold, or cold signaling might interfere with brassinosteroid regulation of the CPD/DWF3 gene. Consistent with this, expression of BRASSINOSTEROID-RESPONSIVE RING-H2 1 (BRH1, At3g61460), whose transcript is downregulated by brassinolide (Molnar et al., 2002), was also downregulated at 6 h after cold stress.

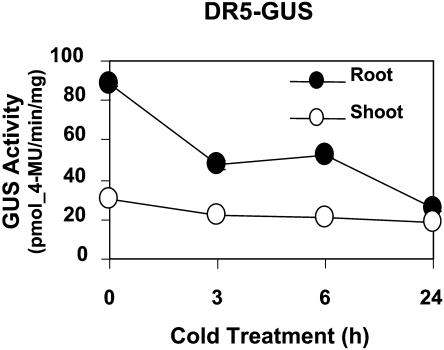

We noticed that the expression of many genes with auxin-related roles was affected by cold stress. Twenty-one auxin-related genes showed cold upregulation or downregulation, and the majority of them (16 genes) were cold downregulated, while only five genes were cold upregulated (Tables 5 and 6). Among the 16 cold downregulated auxin genes, six belong to the SAUR gene family (Table 6). SAUR gene transcripts are very unstable (Hagen and Guilfoyle, 2002). Thus, cold stress may either prevent the stabilization of the SAUR gene transcripts (e.g., by reducing auxin levels) or decrease their transcription.

To examine the possibility of cold regulation of auxin levels, we monitored β-glucuronidase (GUS) activity in Arabidopsis seedlings expressing the DR5-GUS transgene. The DR5-GUS Arabidopsis plant has the GUS reporter gene driven by the synthetic auxin-responsive DR5 promoter, which has been widely used as a reporter for endogenous auxin levels (Ulmasov et al., 1997). The GUS activity in DR5-GUS seedlings decreased after cold treatment (Figure 3), particularly in roots. This suggests that cold may decrease endogenous auxin levels, especially in roots, or interfere with auxin sensitivity. Other cold-affected, auxin-related genes include those in signaling and transcription (At5g20730 and At5g54490), auxin conjugation/inactivation (At1g24100, At4g15550, At1g28130, At2g47750, and At5g54510), auxin biosynthesis (At4g31500 and At4g39950), and polar transport (At2g01420 and At2g36910).

Figure 3.

Quantification of DR5-GUS Activity during Cold Stress.

GUS quantification is shown in pmol·4-MU/min/mg on the y axis during cold treatment (h, x axis) of DR5-GUS–expressing Arabidopsis.

Obviously, cold is not the only factor that downregulates auxin-inducible genes. Wounding has a similar effect (Cheong et al., 2002). One proposed mechanism for downregulation by wounding is suppression of auxin signal transduction by a NPK1-like gene, a putative homolog of ANP1 that negatively regulates auxin-responsive genes (Kovtun et al., 1998). In our microarray study, the NPK1-like gene (At2g30040) was early and transiently upregulated by cold, which suggests that cold repression of auxin-inducible genes might be mediated in a similar way as wounding (see Supplemental Table 2 online). Another proposed possibility of auxin-related gene downregulation by wounding was potentially lower levels of active auxin triggered by wounding (Cheong et al., 2002). This was based on the observation that the gene expression of a nitrilase, an auxin biosynthetic enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of indole-3-acetonitrile to indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), was downregulated and the transcript levels of two IAA glucosyltransferases, auxin conjugating enzymes, were upregulated by wounding (Cheong et al., 2002). In our microarray data, nitrilase genes were not significantly changed by cold, but IAA glucosyltransferase genes (At1g24100 and At4g15550) were downregulated. Therefore, although the disturbance of auxin homeostasis, transport, and signaling might all contribute to the downregulation of auxin-inducible genes by cold, the mechanisms appear to differ between the stresses.

Downregulation of auxin transport and auxin-responsive genes may eventually contribute to reduced plant growth rate under cold stress. Related to the growth regulation, we found that two members of the α-expansin gene family (Lee et al., 2001) were repressed at the late time point by cold (see Supplemental Table 9 online): expansin A1 (At1g69530) and A6 (At2g28950). Interestingly, three expansin-like genes (EXLA1, At3g45970; EXLA2, At4g38400; EXLA3, At3g45960) were cold upregulated (see Supplemental Table 2 online), which suggests that these expansin-like genes may have a distinct function in plant growth.

Cold-Regulated Gene Expression in the ice1 Mutant

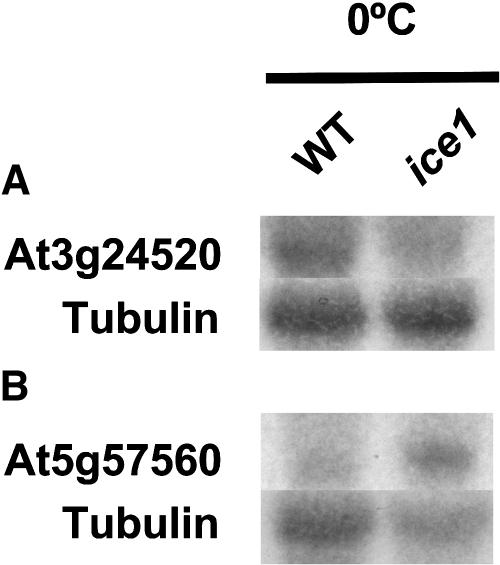

We have previously reported that the bHLH transcription factor ICE1 functions as an upstream regulator of CBF genes (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). The dominant ice1 mutant shows reduced cold induction of CBF3 and several COR (for cold responsive) genes that are under control of CBFs. To understand the role of ICE1 in global gene expression in the cold, the expression of the 939 cold-regulated genes in the wild type was compared with that in the ice1 mutant at each time point during cold stress. As the ice1 mutant was originally isolated due to its lower expression of CBF3 (At4g25480) during cold stress, the CBF3 expression level in both the wild type and ice1 mutants was examined first. With the FDR of 1%, CBF3 expression in ice1 was statistically lower than the wild type only at 3 h after cold treatment. Using RNA gel blot analysis, we have previously observed that CBF3 transcript levels were clearly lower in ice1 than in the wild type at least until 24 h after cold treatment (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). Thus, the FDR of 1% appears to be too strict to be used as a threshold for the comparison of cold-responsive gene expression between the wild type and ice1. Another conventional FDR of 5% appeared to be an appropriate standard, as it rendered CBF3 transcript levels to be significantly lower in ice1 at 3, 6, and 24 h under cold stress. Therefore, 5% FDR was used here for the comparison of 939 cold-responsive genes between the wild type and ice1. The details of the statistical methods are described in Methods, and results from this analysis were confirmed by RNA hybridization with two randomly selected genes showing significantly different transcript levels between the wild type and ice1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

RNA Gel Blot Analysis of Cold-Regulated Genes in the Wild Type and ice1.

(A) At3g24520 (HSF1, 0°C 24 h).

(B) At5g57560 (TCH4, 0°C 0 h). Tubulin was used as a loading control.

Among the 939 cold-regulated genes, the expression of 369 cold-regulated genes was affected in the ice1 mutant (Table 7; see Supplemental Tables 12 and 13 online). Among them were 240 cold upregulated and 129 downregulated genes (Table 7; see Supplemental Tables 12 and 13 online). Thus, the expression of ∼40% of cold-regulated genes was altered in the ice1 mutant in comparison to the wild type. To see if the altered expression affected primarily cold-regulated genes, 939 non-cold-regulated genes were randomly selected, and the gene expression of the random 939 genes was analyzed. The analysis revealed that only the expression of 120 of these genes was significantly different between the wild type and ice1, with 64 being higher and 56 significantly lower in ice1 (Table 7). In summary, the expression of many of cold-regulated genes was affected by the ice1 mutation, and the ice1 mutation has a differential effect on the expression of cold-regulated genes than on that of genes in general.

Table 7.

Comparison of Cold-Regulated Gene Expression between the Wild Type and ice1

| Comparison Time PointsTranscript Level in ice1

|

0 to 24 h

|

0 h

|

3 to 24 h (during Cold)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher | Lower | Subtotal | Higher | Lower | Subtotal | Higher | Lower | Subtotal | |

| Cold upregulated (655) | 142 | 101 | 240a | 132 | 10 | 142 | 56 | 101 | 157 |

| Cold downregulated (284) | 72 | 58 | 129b | 13 | 49 | 62 | 72 | 41 | 112b |

| Cold regulated (939) | 214 | 159 | 369 | 145 | 59 | 204 | 128 | 142 | 269 |

| Random (939) | 64 | 56 | 120 | 41 | 30 | 71 | 50 | 44 | 94 |

Three genes (At1g09070, At1g76590, and At4g15910) belong to both higher and lower categories at a certain time point.

One gene (At4g26950) belongs to both the higher and lower categories at a certain time point.

Numbers in parentheses are total numbers of genes in each category.

We then examined the basal level (i.e., at 0 h) of expression of cold-regulated genes in the wild type and ice1. Basal transcript levels of 204 of the 939 cold-regulated genes were affected in ice1 (Table 7). Interestingly, among ice1-affected cold upregulated genes, a substantially larger number of genes had higher basal transcript levels in ice1 than lower basal levels compared with the wild type (132 genes versus 10 genes). By contrast, ice1-affected cold downregulated genes had more genes with lower basal levels in ice1 than higher basal levels relative to the wild type (49 versus 13) (Table 7). The results suggest that the wild-type ICE1 protein plays a critical role in maintaining the basal expression levels for both cold upregulated and downregulated genes.

A comparison of the expression levels of cold-regulated genes after cold treatment revealed that there are approximately twofold more cold upregulated genes in ice1 with lower expression levels than those with higher expression levels (101 versus 56) (Table 7). By contrast, the number of cold downregulated genes with higher transcript levels in ice1 was higher than that with lower expression levels (72 versus 41) (Table 7). These are opposite tendencies to those observed in the basal transcript levels in ice1. It suggests that ICE1 plays a large role in the cold activation of gene expression as well as in the downregulation of genes.

Because ICE1 is the most upstream transcription factor known in the cascades of gene expression under cold stress (Chinnusamy et al., 2003), we examined in more detail the effect of the ice1 mutation on cold regulation of transcription factors (Tables 8 and 9; see Supplemental Table 11 online). Including CBF3 (At4g25480), the expression of 52 (39.1%) out of the 133 cold-regulated genes involved in transcription was affected by the ice1 mutation (Tables 8 and 9; see Supplemental Table 11 online). Before cold treatments (i.e., 0 h), expression levels of most cold-responsive transcription-related genes were higher in ice1, and all of them belong to cold upregulated genes (Table 8). Interestingly, the expression level of these genes, except for one Zn finger domain gene (At3g28210), became similar to the wild-type level as the duration of cold stress became longer. In other words, at 24 h after cold stress, these transcription-related genes with higher basal transcript levels in ice1 did not show significant difference from the wild-type levels. This suggests that the responsiveness of cold induction (i.e., the rate of gene induction) and the basal levels of these genes are affected in ice1. Our results thus indicate that ICE1 regulates cold tolerance by controlling the basal expression and induction of many cold-responsive transcription factors.

Table 8.

Cold-Regulated Transcription Genes Altered in ice1

| Transcript Level in ice1 at 0°C

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | AGI ID | Kinetics | 0 h | 3 h | 6 h | 24 h | Gene Name |

| AP2 | At1g28370 | ETU | H | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 11 | |||

| At1g77640 | ETU | H | H | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative | |||

| At5g51990 | ETU | L | L | AP2 domain transcription factor-like protein | |||

| At5g53290 | ETU | H | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative | ||||

| At2g23340 | ECU | L | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative | ||||

| At2g40350 | ECU | H | H | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative (DREB2) | |||

| At3g50260 | ECU | H | AP2 domain transcription factor, putative | ||||

| At4g25480 | ECU | L | L | L | DRE binding protein (DREB1A/CBF3) | ||

| At5g07310 | ECU | H | AP2 domain putative transcription factor | ||||

| At2g28550 | LU | L | AP2 domain transcription factor RAP2.7 | ||||

| At4g36900 | LU | L | AP2 domain protein RAP2.10 | ||||

| At4g36920 | LU | H | H | Floral homeotic protein APETALA2 | |||

| Myb | At5g67300 | ETU | H | Myb-related protein, 33.3K | |||

| At5g01200 | LU | L | L | Myb family transcription factor | |||

| At5g16560 | LD | H | Myb family transcription factor | ||||

| bHLH | At1g32640 | ETU | H | bHLH protein (RAP-1); ATMYC2 | |||

| At2g23760 | LU | L | L | BEL1-like homeobox 4 protein (BLH4) | |||

| At1g09250 | LD | L | bHLH protein; tRNA processing; chloroplast | ||||

| At1g18400 | LD | L | L | L | L | Helix-loop-helix protein homolog–related | |

| At1g73830 | LD | L | L | bHLH protein family | |||

| At3g06120 | LD | H | H | bHLH protein family | |||

| bZIP | At2g36270 | LU | H | H | bZIP transcription factor AtbZip39 | ||

| At4g01120 | LU | L | L | G-box binding bZip transcription factor GBF2/AtbZip54 | |||

| At4g34590 | LU | H | H | H | bZIP transcription factor ATB2/Atbzip11 | ||

| GRAS | At1g14920 | LD | L | L | L | Signal response protein (GAI) | |

| HSF | At3g24520 | ECU | L | L | L | HSF1 | |

| MADS | At3g66656 | LD | L | MADS box protein | |||

| NAC | At5g24590 | ETU | L | No apical meristem (NAM) protein family | |||

| At3g10500 | LU | H | H | NAM family protein | |||

| At2g33480 | LD | H | NAM protein family | ||||

| SPB | At1g76580 | ECU | L | L | SPL1-Related3 protein | ||

| Trihelix | At5g01380 | LU | H | Transcription factor GT-3a | |||

| WRKY | At2g38470 | ETU | H | Putative WRKY-type DNA binding protein | |||

| At2g46400 | ETU | H | WRKY family transcription factor | ||||

| At4g01250 | ETU | H | H | WRKY family transcription factor | |||

| At4g31800 | ETU | H | H | WRKY family transcription factor | |||

| At2g30250 | ECU | H | WRKY family transcription factor | ||||

| At1g62300 | LU | H | H | H | Transcription factor WRKY6 | ||

| Zn | At3g55980 | ETU | H | Zn finger (CCCH-type) family protein | |||

| At1g27730 | ECU | H | Salt tolerance Zn finger protein; ZAT10 | ||||

| At5g59820 | ECU | H | H | Zn finger protein Zat12 | |||

| At1g10170 | LU | H | H | NF-X1–type Zn finger family protein | |||

| At1g25250 | LU | L | Zn finger (C2H2 type) family protein | ||||

| At3g28210 | LU | H | H | H | H | Zn finger protein (PMZ)–related | |

| At5g18550 | LU | H | Zn finger–like protein | ||||

| At2g44380 | LD | H | CHP-rich Zn finger protein, putative | ||||

| Not classified | At3g61260 | LU | L | L | L | Putative DNA binding protein | |

| Chromatin | At1g63020 | ECU | H | RNA polymerase IV (RNA polymerase D) subunit; NRPD1a | |||

| At5g10550 | ETD | H | Bromodomain protein-like | ||||

| RNA Metab. | At4g03430 | LU | H | Putative pre-mRNA splicing factor (STA1) | |||

| At4g05410 | LU | H | H | U3 snoRNP-associated–like protein | |||

| At5g46920 | LU | H | Intron maturase, type II family | ||||

H or L indicates that the transcript level is higher or lower, respectively, in ice1 compared with the wild type. SPB, squamosa promoter binding; RNA Metab., RNA metabolism.

Table 9.

Numbers of Cold-Regulated Transcription Genes Altered in ice1

| Category | Gene Number Altered in ice1 |

|---|---|

| AP2/ERF (22) | 12 |

| B3 (1) | 0 |

| bZIP (6) | 3 |

| CCAAT (1) | 0 |

| CG-1/CAMTA4 (1) | 0 |

| GRAS (3) | 1 |

| Homeodomain (2) | 1 |

| HSF (4) | 1 |

| MADS (1) | 1 |

| MYB (12) | 3 |

| bHLH (8) | 5 |

| NAC (10) | 3 |

| SPB (2) | 1 |

| Trihelix (3) | 1 |

| Unclassified DNA domain (1) | 1 |

| WRKY (8) | 6 |

| Zn (29) | 8 |

| Chromatin remodeling (4) | 2 |

| RNA metabolism (6) | 3 |

| Total | 52 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of cold-regulated genes in each category.

Among the transcription-related genes with altered expression in ice1, AP2 domain transcription factors were the major group, followed by bZIPs and WRKYs (Table 9). In particular, the expression of most of the cold-inducible WRKY factors (six out of eight) was enhanced in ice1, and the alteration mostly occurred at either 0 h or early time points (Tables 8 and 9). In fact, WRKY transcription factors and AP2 domain transcription factors were the major early cold-regulated transcription factors (Table 3). Thus, ICE1 seems to preferentially target early or upstream transcription factors in cold-regulated gene expression.

The ice1 mutation also affected the expression of 31 (37.8%) of the 82 cold-regulated genes involved in signal transduction (Tables 10 and 11; see Supplemental Table 10 online). Genes encoding Ca2+-signaling proteins, RLKs, and lipid-signaling proteins were the major genes whose expression was altered in ice1 (Table 11). Expression of other cold-regulated protein kinases and protein phosphatase was largely not changed in ice1. The results suggest that the ICE1 pathway may involve lipid and RLK-mediated processes.

Table 10.

Cold-Regulated Signaling Genes Altered in ice1

| Transcript Level in ice1 at 0°C

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | AGI ID | Kinetics | 0 h | 3 h | 6 h | 24 h | Gene Name |

| Calcium binding | At2g43290 | ETU | H | Putative calcium binding protein | |||

| At5g37770 | ETU | H | Calmodulin-related protein 2, Touch-induced (TCH2) | ||||

| At3g10300 | ECU | H | Calcium binding EF-hand family protein | ||||

| At4g27280 | ECU | H | Calcium binding EF-hand family protein | ||||

| At5g49480 | ECU | H | Sodium-inducible calcium binding protein | ||||

| At3g51920 | LU | H | Putative calmodulin | ||||

| At5g55990 | LU | L | Calcineurin B-like protein 2 (gb|AAC26009.1) | ||||

| At4g16350 | LD | H | Calcineurin B-like protein 6 (CBL6) | ||||

| Protein phosphatase | At3g16800 | LU | L | Protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C), putative | |||

| At5g02760 | ECD | L | L | Protein phosphatase-like protein | |||

| Protein kinase | At1g01140 | ETU | L | SOS2-like protein kinase PKS6/CBL-interacting protein kinase 9 (CIPK9) | |||

| At3g24550 | ETU | L | Protein kinase-related | ||||

| At1g07150 | ECU | H | Protein kinase family; MAPKKK13 | ||||

| At3g57760 | ECU | H | Protein kinase family protein | ||||

| At2g28930 | LU | H | Protein kinase (APK1b) | ||||

| RLK | At1g61380 | LU | H | S-like receptor protein kinase | |||

| At3g53810 | LU | H | H | H | H | Receptor lectin kinase, putative | |

| At1g12460 | LD | L | L | Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase, putative | |||

| At1g34210 | LD | H | Somatic embryogenesis receptor-related kinase | ||||

| At1g68780 | LD | L | L | L | Leucine-rich repeat protein family | ||

| At3g23110 | LD | H | Disease resistance family protein, contains leucine-rich repeat | ||||

| At4g30520 | LD | L | RLK homolog | ||||

| Histine kinase | At5g35750 | LD | L | L | L | Histidine kinase (AHK2) | |

| Response regulator | At4g18020 | LD | H | Pseudoresponse regulator 2 (APRR2) | |||

| Lipid signaling | At4g18010 | ETU | H | IP5PII | |||

| At5g07920 | ECU | L | Diacylglycerol kinase (ATDGK1) | ||||

| At5g58670 | LU | H | H | H | Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C (ATPLC1) | ||

| At5g58690 | LU | L | Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C-line (MZN1.13) | ||||

| At5g58700 | LU | H | Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C4 (PLC4) | ||||

| At5g63770 | LU | H | Diacylglycerol kinase | ||||

| GTP-related | At1g30960 | LU | H | GTP binding protein, ERG-related | |||

H or L indicates that the transcript level is higher or lower, respectively, in ice1 compared with the wild type. Note that pseudoresponse regulators are included in the response regulator category.

Table 11.

Numbers of Cold-Regulated Signaling Genes Altered in ice1

| Category | Gene Number Altered in ice1 |

|---|---|

| Calcium binding protein (15) | 8 |

| Protein phosphatase (12) | 2 |

| Protein kinase (20) | 5 |

| RLK (14) | 7 |

| Blue light receptor (1) | 0 |

| Histidine kinase (1) | 1 |

| Response regulator (5) | 1 |

| Lipid-signaling protein (9) | 6 |

| GTP-related protein (5) | 1 |

| Total (82) | 31 |

Numbers in parentheses indicate the total number of cold-regulated genes in each category.

An examination of genes with plant hormone-related roles in ice1 revealed that ABA- and auxin-related genes were predominantly affected in ice1 (Tables 12 and 13). This indicates that the activation of ICE1 may be upstream of the hormone-related changes during cold regulation.

Table 12.

Cold Upregulated Plant Hormone-Related Genes Altered in ice1

| Transcript Level Altered in ice1

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone | AGI ID | Kinetics | 0 h | 3 h | 6 h | 24 h | Gene Name |

| ABA | At5g52310 | ECU | L | Low-temperature-induced protein 78 | |||

| At1g20440 | ECU | L | Dehydrin (COR47) | ||||

| At1g20450 | ECU | L | L | Dehydrin (ERD10) | |||

| At4g24960 | ECU | L | ABA-induced–like protein | ||||

| At5g15960 | ECU | L | L | Stress-induced protein KIN1 | |||

| At2g36270 | LU | H | H | ABA-responsive element binding protein, putative | |||

| At5g58670 | LU | H | H | H | Phosphoinositide-specific phospholipase C | ||

| At4g15910 | LU | H | L | Drought-induced protein (Di21) | |||

| At1g29395 | LU | L | Similar to the cold acclimation protein WCOR413 in wheat | ||||

| Auxin | At5g35735 | LU | H | Auxin-induced protein family | |||

| Ethylene | At1g28370 | ETU | H | Ethylene-responsive element binding factor 11, putative | |||

H or L indicates that the transcript level is higher or lower, respectively, in ice1 compared with the wild type.

Table 13.

Cold Downregulated Plant Hormone-Related Genes Altered in ice1

| Transcript Level Altered in ice1

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone | AGI ID | Kinetics | 0 h | 3 h | 6 h | 24 h | Gene Name |

| Auxin | At2g45210 | ETD | H | H | H | Putative auxin-regulated protein; SAUR gene family | |

| At4g38840 | ETD | L | Auxin-induced protein like; SAUR gene family | ||||

| At4g39950 | LD | H | H | H | CYP79B2 | ||

| At4g31500 | LD | H | H | CYP83B1 | |||

| At5g54510 | LD | H | Auxin-responsive-related protein | ||||

| At3g25290 | LD | H | H | H | H | Auxin-induced protein family | |

| At2g01420 | LD | L | L | L | L | Auxin transporter splice variant B (PIN4) | |

| At1g29430 | LD | L | L | L | L | Auxin-induced protein, putative; SAUR gene family | |

| At1g29500 | LD | L | L | L | Auxin-induced protein, putative; SAUR gene family | ||

| Cytokinin | At5g35750 | LD | L | L | L | Histidine kinase-related protein; AHK2 | |

| GA | At3g60290 | LD | L | L | SRG1-like protein; GA 20-oxidase | ||

| At1g14920 | LD | L | L | L | GA response modulator (GAI/RGA2) | ||

H or L indicates that the transcript level is higher or lower, respectively, in ice1 compared with the wild type.

Recently, putative CBF3 and CBF2 target genes were identified using Arabidopsis transgenic lines overexpressing CBF3 or CBF2 (Maruyama et al., 2004; Vogel et al., 2005). We compared the reported CBF3- and CBF2-targeted cold-responsive genes with ice1-affected cold-responsive genes. Out of 102 genes identified as cold upregulated CBF3 and CBF2 target genes, 74 are in our cold upregulated gene list. These 74 genes include six CBF3-specific target genes, 18 genes targeted by both CBF2 and CBF3, and 50 CBF2-specific target genes. Four of the six CBF3-specific target genes (67%) were altered in ice1, whereas 19 of the 50 CBF2-specific target genes (38%) were affected by the ice1 mutation (see Supplemental Tables 14 to 16 online). Fifteen of the eighteen genes (83%) targeted by both CBF2 and CBF3 showed altered expression in the ice1 mutant (see Supplemental Tables 14 to 16 online). In addition, we found that only one (At4g02330) out of the 24 cold-responsive ZAT12 target genes (Vogel et al., 2005) was affected by ice1. The results show that the ice1 mutation has a more pronounced effect on the target genes of CBFs, particularly of CBF3, which is consistent with the observation that the dominant ice1 mutation has a very strong effect on the cold induction of CBF3.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified 655 cold upregulated and 284 downregulated genes in Arabidopsis using the Affymetrix Arabidopsis 24,000-gene GeneChip. Many transcription factors were induced during cold stress, particularly during early cold stress. By contrast, only one transcription factor was downregulated early during cold stress. These results suggest that cold responses in plants are initiated mainly by transcriptional activation rather than repression of genes. The downregulation of other transcription factors later in the cold may be the result of early activation of transcription factors. In addition, a number of RNA metabolism genes and chromatin remodeling proteins were also cold regulated, suggesting their involvement in cold-responsive gene regulation.