Abstract

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) and its related receptor (PTHR) are essential regulators of calcium homeostasis and bone physiology. PTH activates PTHR by interacting with a ligand-binding site localized within the N-terminal extracellular domain (the N-domain) and the domain comprising the seven transmembrane helices and the connecting extracellular loops (the J-domain). PTH binding triggers a conformational switch in the receptor, leading to receptor activation and subsequent cellular responses. The process of receptor activation occurs rapidly, within ≈1 s, but the binding event preceding receptor activation is not understood. By recording FRET between tetramethyl-rhodamine in PTH(1-34) and GFP in the N-domain of the receptor, we measured the binding event in real time in living cells. We show that the association time course between PTH(1-34) and PTHR involves a two-step binding process where the agonist initially binds the receptor with a fast time constant (τ ≈ 140 ms) and then with slower kinetics (τ ≈ 1 s). The fast and slow phases were assigned to hormone association to the receptor N- and J domains, respectively. Our data indicate that the slow binding step to the J-domain coincides with a conformational switch in the receptor, also monitored by FRET between the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein and the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein in the PTHR sensor, PTHR enhanced cyan fluorescent protein/enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (PTHRCFP/YFP). These data suggest that the conformational change that switches the receptor into its active state proceeds in a sequential manner, with the first rapid binding step event preceding receptor activation by PTH(1-34).

Keywords: FRET, G protein-coupled receptor, time-resolved signaling, real-time binding, ligand-receptor interaction

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is an 84-aa peptide that regulates concentrations of calcium and phosphate in blood and is of paramount importance in renal and bone metabolism (1). PTH is secreted from the parathyroid glands in response to hypocalcemia and elicits its physiological effects in kidney and bone through the activation of a G protein-coupled receptor, the PTH/PTH-related receptor (PTHR) (2). In response to PTH this receptor leads to activation of adenylyl cyclases (via Gs protein) that in turn increase the intracellular second messenger cAMP, which activates the protein kinase A (PKA)-signaling pathway. PTHR also activates the phospholipase C/protein kinase C-signaling pathways (via Gq protein), although less efficiently than the PKA-signaling pathway (3). PTH(1-34), a synthetic PTH fragment with the first 34 aa of PTH that holds the same pharmacological properties in regard to the regulation of calcium homeostasis as the full-length hormone (4), has recently become a drug (the generic name is teriparatide) approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat osteoporosis (5, 6). The resolution of the mode of interaction of PTH(1-34) to its receptor is critical for understanding the mechanism of action of the hormone and for further progressing in drug development to treat osteoporosis.

We recently showed that activation of PTHR by binding of PTH(1-34) proceeds by fast conformational changes (time constant τ ≈ 1 s) as the receptor switches from a resting to an active state (7). To further our understanding on the PTHR interaction process we resolved the temporal events of PTH(1-34) binding to PTHR in living cells. We measured kinetics of association by FRET between tetramethyl-rhodamine (TMR) (the acceptor fluorophore) conjugated to PTH(1-34) and GFP (the donor fluorophore) inserted into the N-terminal domain of the receptor (Fig. 1A). This study reports the analysis of these kinetics and reveals a two-step process for PTH(1-34) binding, where the first phase mirrored agonist binding to the receptor N-domain with a fast association rate and the second phase reflected association to the J-domain, exhibiting much slower kinetics but temporally coupled to receptor activation.

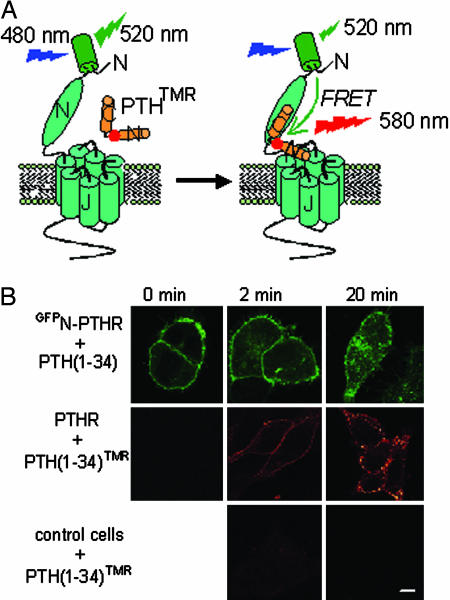

Fig. 1.

Principle of the experiments and functional characterization of GFPN-PTHR and PTH(1-34)TMR. (A) We measured FRET between GFP (green barrel, the donor) and TMR (red circle, the acceptor) introduced, respectively, into the N-terminal extracellular domain of the PTHR and at position 13 in PTH(1-34). The resulting agonist PTH(1-34)TMR and receptor GFPN-PTHR are fully functional (see Fig. 2). Under a fluorescence microscope, a single cell was selectively excited at 480 nm (excitation of GFP), and the changes of the GFP emission fluorescence (515 nm) of the GFPN-PTHR caused by FRET were recorded over time. (B) Visualizing GFPN-PTHR and binding of PTH(1-34)TMR to PTHR in HEK293 cells. Cells expressing GFPN-PTHR (Top), PTHR (Middle), or control (untransfected) cells (Bottom) were incubated with 1 μM PTH(1-34) (Top) or 1 μM PTH(1-34)TMR (Middle and Bottom) for 2 and 20 min. Images were captured by confocal microscopy and are representative of four experiments. (Scale bar: 7 μm.)

Materials and Methods

Peptides. Human PTH(1-34) was purchased from Bachem, and the radioligand [125I]-[Nle-8,21, Tyr-34]-human PTH(1-34)-OH (2,200 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer. Human [Lys-13(Nε-5-carboxy-TMR)]PTH(1-34)NH2 [herein termed PTH(1-34)TMR] was synthesized by Genemed Synthesis (San Francisco). Human [Lys-13(Nε-5-carboxy-TMR)]PTH(1-34)NH2 used in preliminary experiments (data not shown) was also synthesized in our laboratory by the solid-phase approach with fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl chemistry (Supporting Text, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site).

[Aib1,3,M]PTH(1-14) (peptide sequence Aib-V-Aib-E-I-Q-L-M-H-Q-Har-A-K-W-NH2) was kindly provided by T. Gardella (Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston); [Aib1,3,M] refers to the combined modifications of Aib1,3, Gln-10, Har11, Ala-12, and Trp-14 on human PTH(1-14), where Aib is the α-amino-isobutyric acid and Har is homoarginine (8).

Molecular Biology and Cell Culture. Construction of the N-terminally GFP-tagged PTHR (GFPN-PTHR) was performed following a PCR strategy using pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene). cDNA encoding the N-terminal fragment of human PTHR (corresponding to amino acids 1-60) was amplified with primers containing restriction sites for EcoRI (5′) and BamHI (3′). EGFP's cDNA from Clontech was amplified without stop codon with primers containing restriction sites for BamHI (5′) and KpnI (3′). Both PCR products were ligated together after restriction enzymatic digestion with BamHI and subcloned into a previously described pCMV vector encoding the hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged human PTHR cDNA (9) using the restriction sites EcoRI and KpnI. In the resultant construct, GFPN-PTHR, exon 2, and the HA tag at the N terminus of the PTHR (residues 61-101) were replaced with the EGFP sequence preceded by the linker Arg-Leu-Ile-Ser-Gly-Ser. Note that deletion of exon 2 in PTHR does not alter the receptor pharmacology (10). The construct verified by restriction enzyme mapping and sequencing was subcloned into pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) for transient and stable expression in human embryonic kidney (HEK)293 cells. N-terminally GFP-tagged β2-adrenergic receptor construct (GFPN-β2AR) in pcDNA3 was kindly provided by U. Zabel (University of Würzburg) and stably transfected into HEK293 cells for control experiments.

HEK293 cells were cultivated and transfected as described (11). After selection with 400 μg/ml G418 (Merck), stable cell clones showing membrane expression of the GFP-tagged receptors were selected. The HEK293 cell line stably expressing the WT PTHR was kindly provided by E. Blind (University of Würzburg) (12).

Confocal Microscopy. HEK293 cells stably expressing GFPN-PTHR or WT PTHR were plated onto poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips. Cells were incubated with 1 μM PTH(1-34) or 1 μM PTH(1-34)TMR for different times, washed with PBS, and fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed cells were observed with an oil immersion ×63 Plan-Neofluar objective in a Leica TCS laser scanning microscope.

Pharmacology. Ligand binding and measurement of cAMP were performed as described (11) with minimal modifications. For binding studies, stably transfected cells grown in 24-well plates were incubated in DHB buffer (serum-free DMEM containing 20 mM Hepes and 1% BSA) for 1 h at 0°C, followed by a 1.5-h incubation with the same buffer containing 125I-PTH(1-34) (100,000 cpm per well) as a radioligand with or without varying concentrations of unlabeled peptides. Cells were washed three times with iced PBS and extracted with 0.8 M NaOH, and cell-associated 125I-PTH(1-34) was counted.

For cAMP assays, cells grown in 12-well plates were washed twice with Hepes buffer (137 mM NaCl/5 mM KCl/1 mM CaCl2/1 mM MgCl2/20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4) and incubated with isobutylmethylxanthine (0.5 mM) in the same buffer for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were stimulated with varying concentrations of PTH(1-34) or PTH(1-34)TMR at 37°C for 15 additional min. Cellular cAMP was extracted and measured by RIA (Immunotech, Luminy, France; Beckman Coulter). Competition binding studies and concentration-response data were analyzed with the program prism 4.0 (GraphPad, San Diego).

Microscopic FRET Measurements. FRET experiments were performed as described (7) with some modifications. In brief, cells plated on poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips maintained in Hepes buffer containing 0.1% (wt/vol) BSA were placed at room temperature on a Zeiss inverted microscope (Axiovert135) equipped with an oil immersion ×100 Plan-Neofluar objective and a dual emission photometric system (TILL Photonics, Planegg, Germany). Cells were excited with light from a polychrome IV (TILL Photonics). The illumination time was typically set to 25 ms applied with a frequency of 40 Hz. FRET was monitored as the decrease emission of GFP (FGFP) from GFPN-PTHR in the presence of PTH(1-34)TMR, recorded at 520 ± 20 nm (beam splitter 530 DCLP) upon excitation at 480 ± 20 nm (beam splitter 498 DCLP). Note that during the recording of binding events in real time, PTH(1-34)TMR was continuously superfused, and the presence of TMR fluorescence in the FRET channel (emission at 580 nm) caused by the direct excitation of TMR [i.e., bound and unbound PTH(1-34)TMR] at 480 nm does not permit the differentiation of the TMR emission caused by FRET or direct excitation. Because the diminution of GFP fluorescence was caused by FRET between GFP and TMR (see below) we used the decline of GFP fluorescence as readout for the binding event. The spillover of TMR into the 520-nm channel (2%) was negligible at PTH(1-34)TMR concentrations <3 μM and subtracted from the signal of the 520-nm channel at concentrations of 3 μM or higher to give a corrected FGFP. FRET between GFPN-PTHR and PTH(1-34)TMR was also determined by donor (GFP) recovery after acceptor (TMR) photobleaching after three consecutive cycles of 6 min of continuous illumination at 550 nm (orange glass 530 nm, beam splitter 555 DCLP, emission filter HQ605/75).

Recording of Ligand-Induced Changes in FRET. A single cell expressing GFPN-PTHR was continuously superfused with Hepes/BSA buffer and PTH(1-34)TMR at different concentrations with a computer-assisted solenoid valve rapid superfusion device (ALA-VM8, ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY, solution exchange 5-10 ms, ref. 7). Signals detected by avalanche photodiodes were digitalized with an AD converter (Digidata1322A, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) and stored on a personal computer by using clampex 9.0 software (Axon Instruments). The change in the fluorescence emission of GFP as a function of time caused by FRET was analyzed by using nonlinear regression to one- and two-exponential models,

|

where A1 and A2 are the amplitudes of the two phases, A0 is the baseline at t = ∞, k1 and k2 are the rate constants (s-1) for the two phases, and t is the time. The best fits were judged by the analysis of residuals (i.e., differences between the experimental data and the calculated curve fits). Changes in emission caused by photobleaching were systematically subtracted. Data were analyzed with origin 6.1 software (Microcal, Amherst, MA).

Recording cAMP Response by FRET Measurements and Cell Imaging. HEK293 cells stably expressing PTHR were transiently transfected with the previously described Epac-based cAMP sensor (Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) (13). Cells plated on poly-d-lysine-coated glass coverslips maintained in Hepes/BSA buffer were placed at room temperature on a Zeiss inverted microscope (Axiovert135) equipped with an oil immersion ×63 Plan-Neofluar objective and a dual-emission imaging acquisition system coupled to a CoolSNAP-HQ charge-coupled device camera (Visitron Systems, Puchheim, Germany). Samples were excited with a light from a polychrome IV (Till Photonics). Continuous superfusion of the cells with Hepes/BSA buffer and PTH(1-34) was performed as described (13). FRET signals were monitored by using metafluor 5.0 software (Visitron Systems), as the emission ratio at 535 ± 20 nm (acceptor, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein, YFP) and 480 ± 15 nm (donor, enhanced cyan fluorescent protein, CFP) (beam splitter 505 DCXR) upon donor excitation at 436 ± 10 nm. The imaging data were analyzed with metamorph 5.0 (Visitron Systems) and origin 6.1 (Microcal) and corrected for spillover of CFP into the 535-nm channel, direct YFP excitation, and acceptor photobleaching to give a corrected ratio FYFP/FCFP.

Results and Discussion

Functional Characterization of GFPN-PTHR and PTH(1-34)TMR. To study the association between PTH(1-34) and PTHR, we designed and characterized a fluorescent PTH(1-34) where the TMR fluorophore was attached to the Lys side chain at position 13 in PTH(1-34) and a fluorescent PTHR where GFP was introduced into the amino-terminal domain of the receptor (Fig. 1A). The functional properties of PTH(1-34)TMR and GFPN-PTHR stably expressed in HEK293 cells were characterized along three different lines of experiments.

First, confocal microscopy showed that GFPN-PTHR was well expressed at the plasma membrane and underwent time-dependent internalization upon incubation with PTH(1-34) (Fig. 1B Top). PTH(1-34)TMR specifically decorated the cell surface of cells expressing PTHR and internalized with kinetics similar to that observed for GFPN-PTHR in response to PTH(1-34) (Fig. 1B Middle and Bottom).

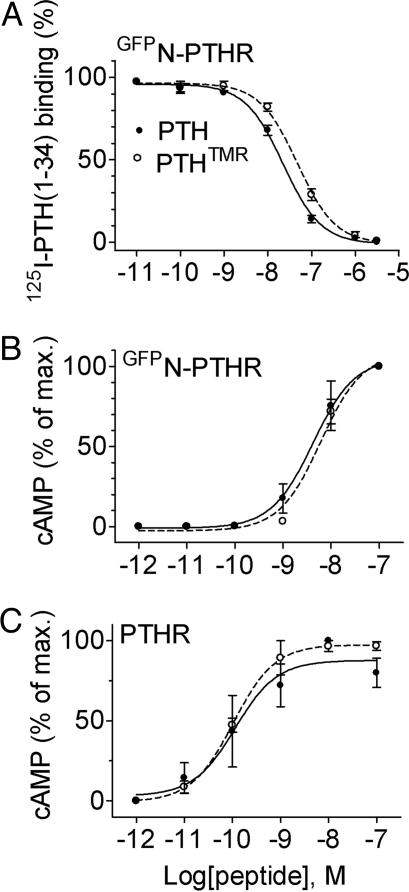

Second, binding competition experiments showed that the affinity of PTH(1-34)TMR (Ki = 47.5 ± 1.1 nM) was close to that of PTH(1-34) for GFPN-PTHR (Ki = 22.3 ± 1.1 nM) (Fig. 2A and Table 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and approximately 1 order of magnitude lower than that of PTH(1-34) for the WT PTHR (Ki = 2.4 ± 0.1 nM) (7). The presence of GFP in the N-terminal domain of the receptor is presumably responsible for the loss in binding affinity.

Fig. 2.

Comparison between the binding (A) and signaling (B and C) properties of PTH(1-34)TMR (○) and PTH(1-34) (•) for GFPN-PTHR or WT PTHR stably expressed in HEK293 cells. cAMP data were calculated as the percentage of the maximum response obtained with PTH(1-34). The data are the means ± SEM of at least three separate experiments carried out in duplicate.

Third, the ability of PTH(1-34)TMR to stimulate maximal cAMP responses in cells expressing the WT PTHR or GFPN-PTHR was indistinguishable from that of PTH(1-34) (Fig. 2 B and C and Table 1), although hormone potencies were reduced for cells expressing GFPN-PTHR (half-maximally effective concentrations, EC50 ranged between 0.10 and 0.20 nM for PTHR and between 4 and 6 nM for GFPN-PTHR) (compare Fig. 2 B and C and Table 1). Taken together, these data indicate the GFPN-PTHR has, in comparison to the WT PTHR, slight altered binding and activation properties and thus is well suited for studying the association of hormone and receptor.

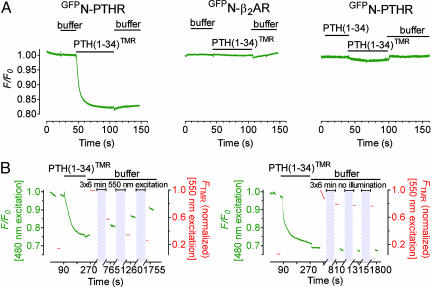

High Resolution of Binding Kinetics. Kinetics of binding of PTH(1-34)TMR to GFPN-PTHR were recorded under a fluorescence microscope at the single-cell level. Fig. 1A illustrates the principle of the experiment. After excitation at 480 nm the maximal fluorescence of GFP was recorded at 520 nm and rapid (<10 ms) addition of PTH(1-34)TMR (1 μM) led to a strong and fast decrease in GFP emission (Fig. 3A Left): the latter decreased by 15% with a half-time t1/2 = 700 ± 20 ms (n = 14). Photo-destruction (i.e., photobleaching) of TMR verified that the decrease in GFP fluorescence was caused by FRET: when GFP (the donor) and TMR (the acceptor) exhibited FRET, then photobleaching of TMR by direct excitation at 550 nm should increase GFP emission at 515 nm. Fig. 3B Left shows that this was exactly the case: after formation of the complex GFPN-PTHR/PTH(1-34)TMR photobleaching of TMR led to recovery of the GFP emission. Control experiments where TMR was not photobleached demonstrated that the fluorescence emission of GFP and TMR moieties was stable over the time frame of the experiments (Fig. 3B Right).

Fig. 3.

Recording binding of PTH(1-34) to PTHR. (A) Time-resolved changes in emission of GFP fluorescence (normalized to the initial value F0) in single HEK293 cells stably expressing GFPN-PTHR or GFPN-β2AR. Shown are the changes induced by rapid superfusion with 1 μM PTH(1-34)TMR, unlabeled PTH(1-34), or buffer. (B) (Left) Photobleaching effect. Emission intensities of GFP (green) and TMR (red) (normalized to the maximal value) from a single cell expressing GFPN-PTHR upon superfusion of PTH(1-34)TMR (1 μM) were subsequently recorded showing GFP emission recovery after photobleaching of TMR. Gray boxes indicate the duration of photobleaching. (Right) Control experiment in the absence of photobleaching. Data are representative of five experiments.

In the following experiments we proved that the decrease in GFP emission corresponds to a specific interaction between PTH(1-34)TMR and GFPN-PTHR. First, we investigated the effect of PTH(1-34)TMR on GFPN-β2AR, which was also well expressed at the cell surface and functionally active but that does not bind PTH(1-34) nor PTH(1-34)TMR (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 3A Center, the addition of PTH(1-34)TMR (1 μM) had no effect on the fluorescence intensity of GFP because of the absence of FRET between PTH(1-34)TMR and GFPN-β2AR. The second experiment showed that sequential addition of PTH(1-34) (1 μM) followed by PTH(1-34)TMR (1 μM) to GFPN-PTHR almost completely prevented the FRET signal, indicating specificity of the response and that little, if any, agonist dissociation occurs during the experiments (Fig. 3A Right). These data demonstrated that the change in GFP emission caused by FRET can be used to specifically record the association between GFPN-PTHR and PTH(1-34)TMR.

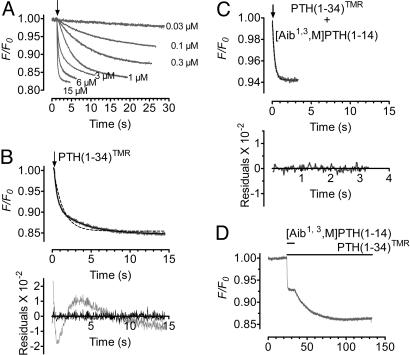

Two-Step Binding Mechanism to Switch On PTHR. Recording the temporal resolution of the FRET signal from a single cell with increasing concentrations of PTH(1-34)TMR allows the kinetic analysis of the interaction of hormone and receptor (Fig. 4A). Binding responses were well fitted to a two-exponential model (Fig. 4B). The biphasic nature of the signal suggests that the association of PTH(1-34) to PTHR involves two binding events. At a maximal concentration of PTH(1-34)TMR (15 μM) the signal rapidly reached equilibrium (t1/2 ≈ 120 ms), and the binding responses followed the sum of two exponential components with time constants τ1 = 140 ± 8 ms (n = 14) for the fast step and τ2 = 1.2 ± 0.1 s (n = 14) for the slower step.

Fig. 4.

Association time courses of PTH(1-34)TMR with GFPN-PTHR. (A) Kinetics of PTH(1-34)TMR binding to GFPN-PTHR recorded by decreases in the fluorescence emission of the GFP moiety. Measurements were recorded in a single cell at 20°C with various concentrations of PTH(1-34)TMR. (B) (Upper) Comparing fits of one-component (dashed line) and two-component (solid line) model for the time course of binding of PTH(1-34)TMR (3 μM). The two-components model accurately describes the binding response. (Lower) The corresponding residuals (differences between the experimental data and calculated fitted curves) are plotted and indicate that the two-component curve fits (in black) the data accurately. (C) Competition between [Aib1,3,M]PTH (1-14) (10 μM) and PTH(1-34)TMR (3 μM) for the binding at the J-domain of GFPN-PTHR. The FRET signal of PTH(1-34)TMR binding in the presence of [Aib1,3,M]PTH (1-14) followed one-component kinetics (dashed line) with kobs values similar to those of the fast component FRET signal for PTH(1-34)TMR alone. (D) Change in FRET in response to 10 μM [Aib1,3,M]PTH(1-14) in the presence or absence of 3 μM PTH(1-34)TMR. Horizontal bars represent the duration of ligand application. The recordings are representative of at least six experiments.

Analysis of the first fast phase showed that the observed rate constant  linearly depends on hormone concentration (Fig. 5A). The strict linearity of the rate constant implies that the first step reflects a simple bimolecular interaction between the hormone (H) and its receptor (R) described by the following reaction,

linearly depends on hormone concentration (Fig. 5A). The strict linearity of the rate constant implies that the first step reflects a simple bimolecular interaction between the hormone (H) and its receptor (R) described by the following reaction,

|

where k1 and k-1 represent the binding and dissociation rate constants, respectively, and the time course of the interaction is defined by  under pseudofirst-order conditions (14). The slope of

under pseudofirst-order conditions (14). The slope of  versus the concentration of hormone gave an association rate constant k1 = (0.7 ± 0.1) × 106 M-1·s-1, which is too low to be under diffusion control (108 to 109 M-1·s-1) but was within the range for interactions between protein—protein or peptide-receptor (105 to 106 M-1·s-1) (15, 16). The intercept with the ordinate axis gave a dissociation rate constant of k-1 = 0.04 ± 0.01 s-1, reflecting the slow dissociation of the bound hormone. The ratio (k-1/k1) yielded a dissociation constant (KD) of 50 nM, which is consistent with the value obtained from radioligand binding analysis (Ki = 47.5 nM).

versus the concentration of hormone gave an association rate constant k1 = (0.7 ± 0.1) × 106 M-1·s-1, which is too low to be under diffusion control (108 to 109 M-1·s-1) but was within the range for interactions between protein—protein or peptide-receptor (105 to 106 M-1·s-1) (15, 16). The intercept with the ordinate axis gave a dissociation rate constant of k-1 = 0.04 ± 0.01 s-1, reflecting the slow dissociation of the bound hormone. The ratio (k-1/k1) yielded a dissociation constant (KD) of 50 nM, which is consistent with the value obtained from radioligand binding analysis (Ki = 47.5 nM).

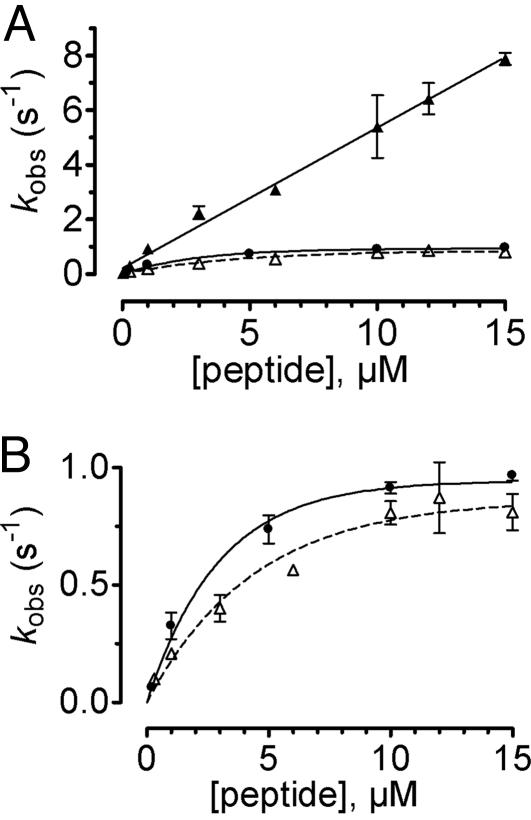

Fig. 5.

Relationship between the observed rate constants kobs and agonist concentration. (A) kobs values were obtained from fitting the time course of PTH(1-34)TMR binding to GFPN-PTHR as shown in Fig. 4 A and B with a sum of two exponential components. kobs values for the first component ( , ▴) were directly proportional to the agonist concentration, whereas kobs values for the second step (

, ▴) were directly proportional to the agonist concentration, whereas kobs values for the second step ( , ▵) followed an hyperbolic dependence on agonist concentration and reach a constant value kobs ≈0.8 s-1. Results for rate constants for PTHR activation (•) originate from our previous study (7). (B) Detail of A showing kobs values for the second binding step and PTHR activation. Data represent the mean ± SEM of at least five separate experiments.

, ▵) followed an hyperbolic dependence on agonist concentration and reach a constant value kobs ≈0.8 s-1. Results for rate constants for PTHR activation (•) originate from our previous study (7). (B) Detail of A showing kobs values for the second binding step and PTHR activation. Data represent the mean ± SEM of at least five separate experiments.

In contrast, the rate constant of the slow phase  followed a hyperbolic dependence on hormone concentrations and reached a constant value at saturating concentrations (Fig. 5). This behavior is consistent with the following two-step reaction

followed a hyperbolic dependence on hormone concentrations and reached a constant value at saturating concentrations (Fig. 5). This behavior is consistent with the following two-step reaction

|

in which the fast binding step is followed by a slower conformational change (denoted by *) and where the time course is defined by

|

(17). At low hormone concentrations, the rate constants increased linearly with hormone concentrations (Fig. 5B), indicating that the hormone binding to PTHR was the rate-limiting step as observed for the first binding step. But at high hormone concentrations the rate constants approached a maximal value, suggesting that a step other than the association of hormone receptor became rate-limiting. The time constant required for this step was ≈1 s (Fig. 5). This step is consistent with a conformational change of the bound agonist. Presumably the bound PTH(1-34) is reoriented to reach its final conformation.

The kinetic profile observed for the second binding step coincides with that recently reported for the activation switch of the PTHR (Fig. 5 and ref. 7), also recorded in a single cell with a similar FRET approach using the receptor sensor PTHRCFP/YFP (Fig. 7). At high concentrations of hormone, rate constants governing the conformational change in the second binding step and in receptor activation were in the same range  (n = 14) for binding and kobs = 0.86-1.03 s-1 (n = 10) for receptor activation (7). These kinetic similarities between the second association step and receptor activation suggest that these two events might be coupled.

(n = 14) for binding and kobs = 0.86-1.03 s-1 (n = 10) for receptor activation (7). These kinetic similarities between the second association step and receptor activation suggest that these two events might be coupled.

To explore the possibility that the slow step of binding related to receptor activation we used [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) (see Materials and Methods), a conformationally constrained PTH(1-14)-derived agonist with increased α-helicity and similar binding and signaling properties as PTH(1-34) (8, 18). Extensive studies have demonstrated that [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) and other PTH(1-14) analogs (8, 19-21) mainly, if not exclusively, bind to the PTHR J-domain in contrast to PTH(1-34), which binds to both receptor's N- and J-domains (22). When [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) is bound, it prevents PTH analogs from occupying their binding site at the J-domain of the receptor (8, 18). In the next experiment, we examined whether the specific association of [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) to the receptor J-domain is able to differentiate the two kinetically distinct phases of PTH(1-34)TMR binding to GFPN-PTHR. As we observed in Fig. 4B, PTH(1-34)TMR (3 μM) association was described by the sum of two exponential phases with association rate constants (kobs) of 2.30 ± 0.14 s-1 and 0.38 ± 0.04 s-1 (n = 12) for the first and second phases, respectively. The corresponding amplitudes (A1 and A2)for these latter phases represented 7 ± 0.6% and 5.5 ± 0.4% of the decline in FRET. However, Fig. 4C shows that simultaneous addition of PTH(1-34)TMR (3 μM) and [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) (10 μM) eliminated the second phase, whereas the first phase remained mostly unchanged (kobs = 2.78 ± 0.15 s-1 and a corresponding amplitude of A = 6.5 ± 0.7%, n = 6). The subsequent removal of [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) restored the full response seen with PTH(1-34)TMR alone (Fig. 4D). These observations are consistent with a model where the interaction of [Aib1,3, M]PTH(1-14) to the receptor J-domain prevents the second PTH(1-34)TMR-binding event to take place. It also implies that residues in the 15-34 portion of PTH interact with the receptor N-domain and dictate the initial binding step. Taken together, these data support a model where the slower second step in agonist binding is consistent with a conformational change of the bound PTH(1-34)TMR accompanying the receptor switch.

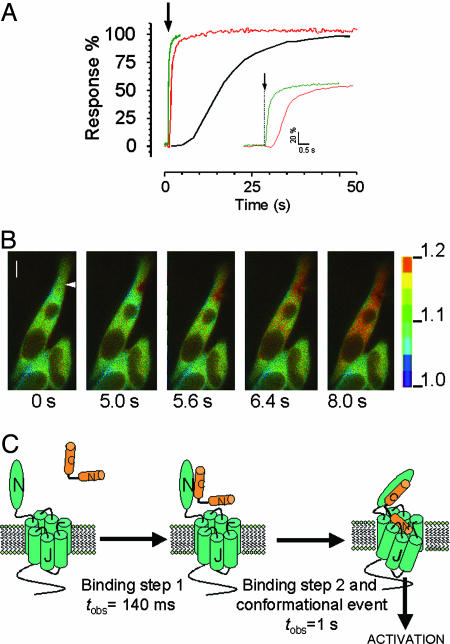

Sequential Events in PTHR Signaling. Because most, if not all, of the hormone receptor associations and subsequent cell responses do not occur at equilibrium, the temporal resolution of such events in real time is important to understand how cell signaling proceeds. In Fig. 6A we show the dynamics of sequential events starting with PTH(1-34) binding followed by PTHR activation and cAMP response recorded at the single-cell level. The data for cAMP were obtained from FRET experiments using a cAMP sensor (Fig. 7), and a representative example is shown in Fig. 6B. These data indicate that a first rapid binding event precedes receptor activation by PTH(1-34) and provide a glimpse of the sequential events occurring in real time for PTHR signaling at the single-cell level.

Fig. 6.

Time-resolved events for PTHR: binding, activation, and signaling. (A) Comparative recording of PTH(1-34)TMR (10 μM) binding to GFPN-PTHR (this study) (green), activation of PTHRCFP/YFP by PTH(1-34) (10 μM) (red) (ref. 7 and Fig. 7A) and PTH(1-34) (10 μM) mediated-cAMP response upon PTHR activation (black) (B and Fig. 7B), all performed at the single-cell level. The recordings are expressed as percentage of the respective maximal response and are representative of at least 15 independent experiments for binding and activation and 5 for cAMP response. (B) FRET imaging of PTHR-mediated cAMP signaling. HEK293 cells stably expressing PTHR were transiently transfected with the cAMP sensor Epac1CFP/YFP (13) to record cAMP synthesis in response to PTH(1-34). Shown is the FRET ratio presented as pseudocolored image (fluorescence emission at 480 nm/fluorescence emission at 535 nm) before and after stimulation of a single cell with 10 μM PTH(1-34) via a pipette indicated by an arrow at t = 0 s. The scale bar on the right indicates the pseudocolored scale of the fluorescence ratios. The inner bar represents 5 μm. (C) Mechanistic model for PTHR activation adapted from ref. 22. Upon PTH(1-34) binding there are two rates of association, a faster one that corresponds to agonist binding to the receptor N-domain and is strictly concentration-dependent, followed by a slower binding step to the receptor J-domain that is coupled to receptor activation.

Conclusion

Several mutagenesis and photo-affinity cross-linking experiments led to a two-site mode of PTH(1-34) binding to PTHR. In this model the N terminus extracellular part of PTHR comprising ≈160 residues (the receptor N-domain) is the principal binding site for the carboxyl-terminal region 23-34 of PTH(1-34), whereas the extracellular loops and transmembrane helices of PTHR (the receptor J-domain) bind the N-terminal 1-19 domain of the hormone (22, 23). Given that residues 1-3 in this latter domain are essential in inducing receptor activation (8), PTH binding to the J-domain is thought to drive receptor activation and subsequent G protein coupling.

Direct recording of PTH(1-34) association to PTHR provided information on the mechanism of hormone binding to its receptor and established a relation between an early agonist-binding step and a second receptor activation step in living cells. The results presented here are consistent with the mechanistic model of Gensure et al. (24), which proposes that the disordered N-terminal residues of PTH(1-34) might become conformationally constrained upon association to the receptor. Extending this hypothesis to our present data, we propose a model in Fig. 6C where PTH(1-34) initially binds to the receptor N-domain with fast kinetics strictly dependent on agonist concentrations (kobs ≈ 106 M-1·s-1), and next binds the receptor J-domain to adopt an active conformation. This second event coincides with the slower (kobs ≈ 1 s-1) turn-on switch of the receptor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank T. J. Gardella for providing [Aib1,3,M]PTH(1-14) and U. Zabel for providing the plasmid encoding GFPN-β2AR. Critical discussions with G. S. Harms (University of Würzburg) and M. Bünemann (University of Würzburg) were most valuable for the development of this project. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Leibniz Award to M.J.L.) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Author contributions: J.-P.V. designed research; M.C. and V.O.N. performed research; D.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; M.C., M.J.L., and J.-P.V. analyzed data; and J.-P.V. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Abbreviations: Aib, α-amino-isobutyric acid; GFPN-β2AR, N-terminally GFP-tagged β2-adrenergic receptor; CFP, enhanced cyan fluorescent protein; Har, homoarginine; HEK, human embryonic kidney; PTH, parathyroid hormone; PTHR, PTH/PTH-related peptide receptor; TMR, tetramethyl-rhodamine; PTH(1-34)TMR, Lys-13(Nε-5-carboxy-TMR)]PTH(1-34)NH2; GFPN-PTHR, N-terminally GFP-tagged PTHR; YFP, enhanced yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- 1.Mannstadt, M., Jüppner, H. & Gardella, T. J. (1999) Am. J. Physiol. 277, F665-F675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jüppner, H., Abou-Samra, A. B., Freeman, M., Kong, X. F., Schipani, E., Richards, J., Kolakowski, L. F., Jr., Hock, J., Potts, J. T., Jr., Kronenberg, H. M., et al. (1991) Science 254, 1024-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abou-Samra, A. B., Jüppner, H., Force, T., Freeman, M. W., Kong, X. F., Schipani, E., Urena, P., Richards, J., Bonventre, J. V., Potts, J. T., Jr., et al. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89, 2732-2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tregear, G. W., Van Rietschoten, J., Greene, E., Keutmann, H. T., Niall, H. D., Reit, B., Parsons, J. A. & Potts, J. T., Jr. (1973) Endocrinology 93, 1349-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neer, R. M., Arnaud, C. D., Zanchetta, J. R., Prince, R., Gaich, G. A., Reginster, J. Y., Hodsman, A. B., Eriksen, E. F., Ish-Shalom, S., Genant, H. K., et al. (2001) N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1434-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qin, L., Raggatt, L. J. & Partridge, N. C. (2004) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 15, 60-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vilardaga, J.-P., Bünemann, M., Krasel, C., Castro, M. & Lohse, M. J. (2003) Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 807-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu, N., Guo, J. & Gardella, T. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 49003-49012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castro, M., Dicker, F., Vilardaga, J.-P., Krasel, C., Bernhardt, M. & Lohse, M. J. (2002) Endocrinology 143, 3854-3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, C., Gardella, T. J., Abou-Samra, A. B., Nussbaum, S. R., Segre, G. V., Potts, J. T., Jr., Kronenberg, H. M. & Juppner, H. (1994) Endocrinology 135, 1488-1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilardaga, J.-P., Krasel, C., Chauvin, S., Bambino, T., Lohse, M. J. & Nissenson, R. A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 8121-8129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blind, E., Bambino, T. & Nissenson, R. A. (1995) Endocrinology 136, 4271-4277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nikolaev, V. O., Bünemann, M., Hein, L., Hannawacker, A. & Lohse, M. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37215-37218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiland, G. A. & Molinoff, P. (1981) Life Sci. 29, 313-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlosshauer, M. & Baker, D. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 1660-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palanche, T., Ilien, B., Zoffmann, S., Reck, M. P., Bucher, B., Edelstein, S. J. & Galzi, J. L. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34853-34861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strickland, S., Palmer, G. & Massey, V. (1975) J. Biol. Chem. 250, 4048-4052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu, N., Dean, T., Khatri, A. & Gardella, T. J. (2004) J. Bone Miner. Res. 19, 2078-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luck, M. D., Carter, P. H. & Gardella, T. J. (1999) Mol. Endocrinol. 13, 670-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimizu, M., Potts, J. T., Jr. & Gardella, T. J. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21836-21843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimizu, M., Carter, P. H., Khatri, A., Potts, J. T., Jr. & Gardella, T. J. (2001) Endocrinology 142, 3068-3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoare, S. R., Gardella, T. J. & Usdin, T. B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7741-7753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardella, T. J. & Jüppner, H. (2001) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12, 210-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gensure, R. C., Gardella, T. J. & Jüppner, H. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328, 666-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.