Abstract

Baylor University Medical Center established a pain initiative group in 1996 to research the effectiveness of pain management throughout the hospital. After analyzing 300 patient surveys, the group undertook an intensive program to educate physicians, nurses, and patients regarding newer pain management techniques. The outcome of this educational initiative was reassessed in 2001 based on surveys completed by 100 patients after discharge. Results showed marked improvement in patient education regarding pain management. In 2001, 93% of patients were offered education and choices regarding pain management vs only 36% in 1996. Fewer patients were afraid to “bother” their nurses to ask for pain medication (3% in 2001 vs 14% in 1996). Waiting time for administration of analgesics decreased considerably. The number of patients reporting moderate to severe pain decreased significantly since 1996, yet the overall satisfaction with pain relief remained high and did not change significantly. The overall incidence of patients reporting moderate to severe pain was significantly less at Baylor than the national average. In conclusion, attitudes, misconceptions, and fears about pain management can be changed with intensive educational programs.

Over the past several decades, undertreatment of pain in the hospitalized patient has been the rule rather than the exception. An order for intramuscular meperidine every 4 hours has been the traditional method for pain management, even into the early 1990s. Physicians and nurses routinely felt that intramuscular narcotics provided adequate relief to their patients, although up to 75% of patients were still rating their pain as moderate to severe (1).

In the 1980s, research began to show that health care providers' attitudes, lack of education regarding narcotic pharmacology, and fears related to addiction or respiratory depression greatly influenced the quality of pain management a patient received (2). In 1991, the American Pain Society developed guidelines to improve the treatment of acute pain in hospitalized patients (3). However, lack of awareness of these guidelines and lack of a standardized pain assessment prevented their widespread use. In 1995, the American Pain Society created the phrase “pain: the fifth vital sign” to elevate awareness of pain treatment among health care professionals (4). The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) subsequently implemented standards for pain management in an attempt to improve pain management in hospitalized patients (5).

Because of the new JCAHO standards, Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) established a pain initiative committee to research the quality of pain management throughout the hospital. Original data regarding pain management were collected in 1996 based on surveys that patients completed after hospital discharge. Subsequently, an intensive program was undertaken to educate physicians, nurses, and patients regarding newer pain management options. In 2001, surveys were again collected from patients regarding pain management while at BUMC.

This article addresses the information gained in the surveys and the changes in pain management at BUMC between 1996 and 2001.

METHODS

Surveys were sent to 300 patients who were hospitalized for surgery in 1996. All surgical subspecialties were equally represented. The survey was developed by Abbott Laboratories (Chicago, 111) to assess pain management effectiveness, patient perceptions, and complications in hospitalized patients. This survey was made available to all hospitals so that data from similar-sized institutions could be compared.

After the collection of data in 1996, the pain initiative committee undertook an intensive program to educate patients, nurses, and physicians about pain management techniques and options. Patients were educated about pain management through special programs shown on the BUMC television system during their hospitalization. Videos developed by the Pain Center physicians were made available to physicians' offices to distribute to patients at the time of the preoperative evaluation. The videos, which included information on pain assessment and treatment, were devised to improve patient knowledge and communication during the perioperative period. Through day conferences and educational modules, nurses were educated about pharmacology of opiates, attitudes regarding addiction, fear of respiratory depression, pain assessment as the fifth vital sign, proper charting of pain complaints, and the importance of rapid treatment of acute pain. Physicians were educated by grand rounds presentations, publications in BUMC Proceedings and information on new JCAHO standards for pain management. Policies were implemented after 1996 to require nurses to chart pain as a fifth vital sign. Nurses were also required to act on any complaint of pain above a 7 on a pain scale of 0 to 10.

In 2001, surveys were sent to 100 patients who were hospitalized for surgery in 2001. These results were compared with the results from 1996, as well as with the national averages collected by Abbott Laboratories and used as a national benchmark. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test and chi-square test. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient education and perceptions

Overall, patients were better educated about pain relief in 2001 and had better experiences (Table 1). The following three changes in perceptions were statistically significant. First, in 1996, 36% of patients reported that they had received education regarding postoperative pain control; this number improved to 93% in 2001 based on the patient education initiatives. Second, fewer patients in 2001 were concerned about “bothering” their nurse for pain medication (3% in 2001 vs 14% in 1996). Third, the number of patients who had fears regarding addiction to pain medication decreased from 17% in 1996 to 4% in 2001. In addition, fewer patients in 2001 reported that they never had good pain relief.

Table 1.

Patient responses to a pain management survey in 2001 and 1996 at Baylor University Medical Center

| % saying yes | |||

| Survey item | 2001 | 1996 | P value |

| Hospital staff explained how pain would be relieved after surgery | 93 | 36 | 0.0001* |

| Method of pain relief was too painful | 0 | 6 | 0.0117* |

| Had to wait too long to get pain medicine | 3 | 7 | 0.1517 |

| Pain relief was too slow | 5 | 7 | 0.4128 |

| Never had good pain relief | 6 | 9 | 0.3314 |

| Concerned about bothering nurse to ask for pain medicine | 3 | 14 | 0.0023* |

| Concerned about becoming addicted to pain medicine | 4 | 17 | 0.0009* |

*Significant at 0.05 level.

Adverse reactions

Complications of pain control modalities remained about the same from 1996 to 2001 (Table 2). The incidence of nausea and skin abrasion decreased. At the same time, the incidence of itching and urinary retention increased, reflecting the increased use of epidural narcotics for postoperative pain management in 2001. Despite increased use of intravenous narcotics, the incidence of respiratory depression decreased slightly. In addition, no patients in 2001 indicated that the method of pain relief was too painful, compared with 6% in 1996 (Table 1).

Table 2.

Adverse reactions and complications to pain management reported on patient surveys in 2001 and 1996 at Baylor University Medical Center

| 2001 (n = 100) | 1996 (n = 300) | |

| Adverse reaction/complication | Number (%) | Number (%) |

| Patients with any complication | 7 (7%) | 20 (7%) |

| Catheter migration | 0 | 0 |

| Device or operator related | 0 | 0 |

| Excessive sedation | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Failed epidural block | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 |

| Infection at catheter site | 0 | 0 |

| Major cardiovascular complication | 0 | 0 |

| Motor block interfering with ambulation | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory depression | 0 | 2 (1%) |

| Itching | 4 (4%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 5 (2%) |

| Skin abrasion | 0 | 5 (2%) |

| Spinal headache | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary retention | 2 (2%) | 0 |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 7 (2%) |

| Hand swelling: 1 | Infiltrated IV: 2 | |

| Hallucinations: 2 |

Waiting time for receiving medication

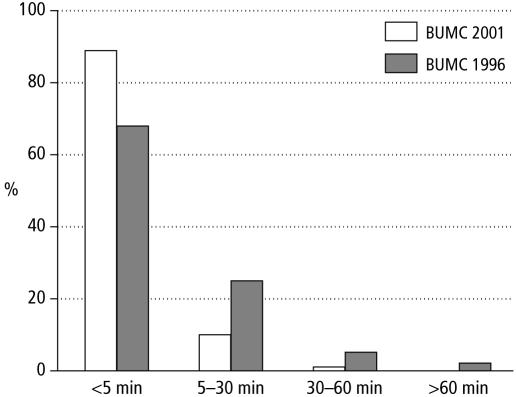

The waiting time for receiving an analgesic after reporting pain decreased between 1996 and 2001, although this was not statistically different (Figure 1). In 2001, 89% of patients received medication in <5 minutes after requesting something for pain. Only 10% of patients had to wait 5 to 30 minutes for an analgesic in 2001 vs 23% of patients in 1996. No patients had to wait >60 minutes in 2001 vs 4% of patients in 1996.

Figure 1.

Time required for delivery of analgesic in hospitalized patients.

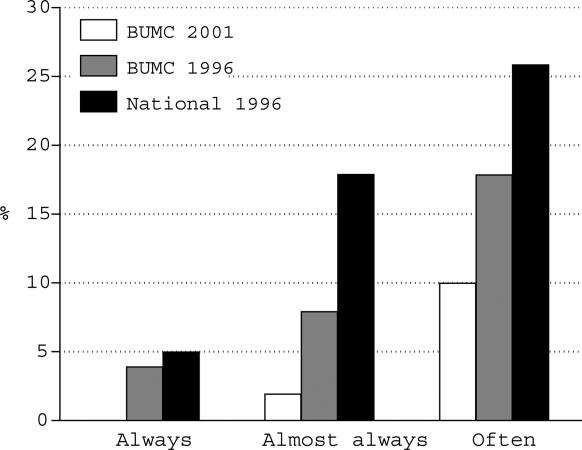

Reports of moderate to severe pain

Patients were asked to record how often their pain reached the moderate to severe level on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = always, 5 = never) (Figure 2). The mean score in 1996 was 3.34. The score improved to 4.43 in 2001, a highly significant change (P = 0.000001) (effect size = 1.54; where >0.8 was significant for a large effect). In 1996, 4% of patients said their pain was never controlled and always in the moderate to severe range as opposed to 0% of patients in 2001. Further, 18% of patients in 1996 said their pain was often at the moderate to severe level compared with 10% in 2001.

Figure 2.

Frequency of patients reporting moderate to severe pain during hos-pitalization.

DISCUSSION

Postoperative pain management at BUMC has improved significantly over the past 5 years. This improvement was initiated with the implementation of new JCAHO standards and requirements in pain management. The most striking difference in the past 5 years has been the amount of time patients spent in moderate to severe pain (vs mild pain). Even though the overall satisfaction with pain management at BUMC was not statistically different between 1996 and 2001 (both surveys showed high patient satisfaction), the amount of time patients complained of moderate to severe pain decreased significantly (P = 0.000001). This is a tribute to the more aggressive assessment and treatment of pain by nurses and the increased familiarity regarding newer pain management techniques by physicians. Pain evaluation at BUMC has indeed become the fifth vital sign.

Another significant change resulting from the pain management initiative over the past 5 years has been the number of patients who have been well educated about postoperative pain techniques prior to their surgery. In 2001, 93% of patients reported being educated about pain management as opposed to 36% in 1996. The better-educated patients in 2001 were much less intimidated about asking a nurse for pain medication and had much less concern about addiction.

The incidence of complications did not increase in 2001 despite an increase use of intravenous analgesics, increased use of specialized techniques such as intraspinal narcotic infusions, and preemptive analgesic with nerve blocks.

It has been very encouraging to see that in 2001, 89% of patients at BUMC received analgesics within 5 minutes of requesting medication and no patients reported having to wait >60 minutes to receive pain medication.

Finally, compared with other equally sized hospitals, health care providers at BUMC are well above average in treating moderate to severe pain in postoperative patients (Figure 2).

CONCLUSION

The days of standard orders for meperidine as needed seem to be disappearing with increased knowledge and education about newer pain management options. The pain initiative committee at BUMC has shown that attitudes, misconceptions, and fears about pain management can be changed with intensive educational programs. As a result of these efforts, moderate to severe pain has been more aggressively treated and overall patient satisfaction with pain control remains high.

With the recent emphasis on pain management included in JCAHO standards, we must continue to strive to minimize pain not only in postoperative patients but in all hospitalized patients. By understanding the importance of effective pain management, we will achieve better clinical outcomes and higher patient satisfaction throughout BUMC.

References

- 1.Cohen FL. Postsurgical pain relief: patients' status and nurses' medication choices. Pain. 1980;9:265–274. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(80)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weis OF, Sriwatanakul K, Alloza JL, Weintraub M, Lasagna L. Attitudes of patients, housestaff, and nurses toward postoperative analgesic care. Anesth Analg. 1983;62:70–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Pain Society Quality of Care Committee Quality improvement guidelines for the treatment of acute pain and cancer pain. JAMA. 1995;274:1874–1880. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530230060032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell J. Pain: the fifth vital sign [presidential address, American Pain Society, Los Angeles, Calif November 11, 1995]. Abstract available at http://www.ampainsoc.org/advocacy/fifth.htm

- 5.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations . Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals, Update 3. Oakbrook Terrace, Ill: JCAHO; 1999. [Google Scholar]